PAWTUCKET

Sam Patch first saw Pawtucket in 1807, when he was seven years old. It was an old village, founded in 1672 at the falls of the Blackstone River, four miles north of Providence, Rhode Island. The Englishman Samuel Slater had built America’s first water-frame cotton-spinning mill there in 1790. In 1807 three mills stood beside the falls, and they were beginning to edge out the family-owned anchor forges, snuff mills, nail factories, and artisan shops of the old town. Pawtucket was becoming America’s first textile manufacturing town, and the Patches were one of the first mill families.1

Postrevolutionary America was an overwhelmingly rural republic, and proponents of domestic manufactures insisted that factories would threaten neither agriculture nor the independence of farmers. The clear streams and abundant water power of the New England and mid-Atlantic states would encourage manufacturers to scatter their mills through the countryside, and these would provide employment for children and women from poor farm households. Alexander Hamilton explained some of the advantages of this system: “The husbandman himself experiences a new source of profit and support from the increased industry of his wife and daughters; invited and stimulated by the

demands of the neighboring manufactories.” Marginal farmers would continue to farm, securing their independence through new and more profitable forms of dependence for their wives and children. Thus Americans, said the promoters, could enjoy domestic manufactured goods without threats to agriculture, and without the European messiness of industrial cities or an industrial working class. There would, they promised, be no Manchesters in America.2

At first, Samuel Slater’s Pawtucket kept that promise. His earliest mill workers were children of his partners and associates, then the children of Pawtucket artisans and farmers. Within a few years, however, he was searching beyond the neighborhood for mill hands and outworkers. Slater needed women and children, and he advertised for widows with large families. What he found was whole families headed by propertyless, destitute men. The Patches were one of these.

As the new families struggled into Pawtucket, Slater and the other mill owners began referring to the workers as “poor children,” “that description of people,” “those who are dependant on daily labor for support.” A Baptist minister who worked with the new people disclosed that the moral “condition of the factory help was deplorable” and dubbed them “children of misfortune.” Mill labor was stigmatized, and artisans and farmers (indeed any father who could manage without the wages of his children) took their daughters and sons out of the mills. A widening flood of destitute migrants took their places, and the mill families became a separate and despised group of people. The Baptist preacher recalled that these families were not only poor but prone to thievery, violence, and drunkenness: “The cotton mill business has brought in a large influx of people,” he said, “who came in the Second Class cars. Such was the prejudice against the business that few others could be had, and the highways and hedges had to be searched even for them. A body of loafers was on hand before, who were, by turns, inmates of the tippling shops and the

poor house, and not infrequently found in the gutter … . Bangall, Hardscrabble, Bungtown, Pilfershire, &c. were … appropriate epithets for the place.” In 1830 a travel guidebook (one that tried to be optimistic about most places) warned that in Pawtucket “the influx of strangers, many of them poor and ignorant foreigners, and most of them removed from the wholesome restraints of a better society, has produced unfavourable effects on habits and morals; which is the worst feature in the manufacturing system.” America had its first little Manchester.3

It must have been a bewildered Sam Patch who, at the age of seven, stood with his father, mother, and four brothers and sisters and looked at Pawtucket for the first time. The Patches had spent the previous few years in the fishing village of Marblehead, in Massachusetts, but they had lost their house there, and the father had taken to drink and no longer worked. Before Marblehead, Sam’s family had lived on farms surrounded by his mother’s kin, but Sam did not remember those places. He would grow up in Pawtucket, shaped by his work and workmates in the mills. He would also be formed by the disorder of this new mill town, and he played his own part in making that disorder. Sam Patch was a product of family history as well—of the long train of disinheritance, uncertainty, and moral disintegration that had destroyed his father and delivered his family to Pawtucket. Sam could not remember much of that history, and his mother would try to hide it. But it shaped Sam Patch in ways he would never outrun.

Sam Patch was the son of Mayo Greenleaf Patch, a marginal farmer and cottage shoemaker from northeastern Massachusetts, who went by the name of Greenleaf.4 The life of Greenleaf Patch was shadowed by two burdensome and uncomfortable facts. The first was the immense value that his New England neighbors placed on economic independence and the ownership of land. In postrevolutionary Massachusetts, freehold tenure conferred not

only economic security but personal and moral independence, the ability to support and govern a family, political rights, and the respect of one’s neighbors and oneself. New Englanders trusted the man who owned land. They feared and despised the man who did not. The second fact was that in the late eighteenth century increasing numbers of men owned no land. Greenleaf Patch was one of them. 5

Like nearly everyone else in revolutionary Massachusetts, Greenleaf Patch was descended from yeoman stock. His family had come to Salem from England in 1636, and they worked a farm in nearby Wenham for more than a century. The Patches were church members and farm owners, and their men served regularly in the militia and in township offices. Greenleaf’s father, grandfather, and great-grandfather all served terms as selectmen of Wenham. His great-grandfather was that town’s representative to the Massachusetts General Court. His older brother was a militiaman who fought on the first day of the American Revolution. 6

Though the Patches were an old and familiar family in Wenham, in the eighteenth century they were in trouble. Like thousands of New Englanders, they owned small farms and had many children, and by mid-century it was becoming clear that young Patch men would not inherit enough to enjoy the material standards established by their fathers. The farm on which Mayo Greenleaf Patch was born exemplified those troubles. His father, Timothy Patch, Jr., had inherited a house, an eighteen-acre farm, and eleven acres of outlying meadow and woodland at his own father’s death in 1751. Next door, Timothy’s brother Samuel worked the remaining nine acres of what had been their father’s farmstead. The father had known that neither of his sons could make farms of these small plots, and he demanded that they share resources. His will granted Timothy access to a shop and cider mill that lay on Samuel’s land, and it drew the boundary between them through the only barn on the property. It was the

end of the line: further subdivision would make both farms unworkable.7

Timothy Patch’s situation was precarious, and he made it worse by overextending himself, both as a landholder and as a father. Timothy was forty-three years old when he inherited his farm in 1751, and he was busy buying pieces of woodland, upland, and meadow all over Wenham. Evidently he speculated in marginal land and/or shifted from farming to livestock raising, which he did on credit and on a fairly large scale. By the early 1760s Timothy Patch held title to 114 acres, nearly all of it in small plots of poor land. These were speculative investments that he may have made to provide for an impossibly large number of heirs: he was already the father of ten children when he inherited his farm in 1751, and in succeeding years he was widowed and remarried and had two more daughters and a son. In all, he fathered ten children who survived to adulthood. The youngest was a son born in 1766. Timothy named him Mayo Greenleaf.8

Greenleaf Patch’s life began badly: his father went bankrupt in the year of his birth. Timothy had transferred the house and farm to his two oldest sons several years earlier, possibly to keep them out of the hands of creditors. Then, in 1766, the creditors began making trouble. In September Timothy relinquished twenty acres of his outlying land to satisfy a debt. By March 1767 he had lost five court cases and had sold all his remaining land to pay debts and court costs, and he was preparing to leave Wenham. It was the end of his family’s history in that town. Timothy’s first two sons stayed on, but both left Wenham before their deaths, and none of the other children established households in the neighborhood. After a century as substantial farmers and local leaders, the Patch family disappeared from the records of Wenham.9

The father’s wanderings after that cannot be traced with certainty. Timothy may have stayed in the neighboring towns of Andover and Danvers. A neighbor sued a Timothy Patch in Andover

(a few miles northwest of Wenham) in 1770; citizens of Danvers launched seven lawsuits against a Timothy Patch between 1779 and 1783. Some of these cases involved considerable sums of money, but the last of them accused the seventy-four-year-old Timothy of stealing firewood. That is all that we can know about the Patch family during the childhood of Mayo Greenleaf Patch.10

About the childhood itself we know nothing. Young Greenleaf may have shared his father’s moves, but it is just as likely that he stayed with relatives in Wenham, for he eventually named his own children after members of the household of his brother Isaac in that town. We know also that young Greenleaf Patch learned how to make shoes, and as his first independent appearance in the civic records came at the age of twenty-one, we might guess that he served a formal, live-in apprenticeship. But all these points rest on speculation. Only this is certain: Greenleaf Patch was the tenth and youngest child of a family that broke and scattered in the year of his birth, and he entered adulthood alone and without visible resources.

In 1787 Mayo Greenleaf Patch appeared in the Second (North) Parish of Reading, Massachusetts—fifteen miles north of Boston and about the same distance west of Wenham. He was twenty-one years old and unmarried, and he owned almost nothing. He had no relatives in Reading. Indeed, no one named Patch had ever appeared in the town’s records. In a world where property was inherited and where kinfolk were essential social and economic assets, young Greenleaf Patch had inherited nothing and lived alone.11

Greenleaf soon took steps that improved his prospects. In July 1788 he married Abigail McIntire in North Reading. He was twenty-two years old; she was seventeen and pregnant. This early marriage is most easily explained as an unfortunate accident, but

from the standpoint of Greenleaf Patch it was not unfortunate at all, for it put him into a family that possessed resources his own family had lost. For the next twelve years, Patch’s livelihood and ambitions centered on the McIntires and their land.12

The McIntires were descendants of Scots soldiers who had supported the accession of Charles II after the Puritans executed Charles I in 1649. They fought an English army led by Oliver Cromwell at Dunbar in 1650 and suffered a disastrous defeat. Three thousand Scots died on the field, nine thousand ran off, and ten thousand were taken prisoner. Cromwell released the wounded and force-marched the others south and imprisoned them in the cathedral at Durham. Only three thousand survived the march, and about half of those died in the cathedral. After a long and hellish imprisonment, the half-starved survivors were transported to English colonies in the Caribbean and the North American mainland.13

The ancestors of Greenleaf’s pregnant young bride had found themselves exiled to the northern reaches of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, in what is now Maine. Some walked south, and Philip McIntire helped to pioneer North Reading in the 1650s. Over the years, the Mclntires intermarried with their old Puritan enemies and joined their Congregational church, and by the 1780s McIntire households (now as much English as Scots) were scattered through the North Parish. Archelaus McIntire, Abigail’s father, headed the most prosperous of those households. Archelaus had been an eldest son, and he inherited the family farm intact. He kept that farm and added to it, and by 1790 he owned ninety-seven acres in North Reading and patches of meadowland in two neighboring townships, a flock of seventeen sheep, cattle and oxen and other animals, and enough personal property to indicate comfort and material decency, if not wealth. Of 122 taxpayers in the North Parish in 1792, the estate of Archelaus McIntire ranked 23rd.14

In 1788, when Archelaus McIntire learned that his youngest

daughter was pregnant and would marry Mayo Greenleaf Patch, he may have been angry. But he had seen such things before. One in three Massachusetts women of his daughter’s generation was pregnant on her wedding day, and the McIntires had contributed amply to that figure: Archelaus himself had been born three months after his parents’ wedding in 1729; an older daughter had conceived a child at the age of fourteen; his only son would marry a pregnant lover in 1795.15

Faced with this early pregnancy, Archelaus McIntire determined to make the best of a bad situation. In the winter of 1789-90 he loaned Greenleaf Patch the cost of a shoemaker’s shop and a small house and granted him use of the land on which they stood. At a stroke, Mayo Greenleaf Patch was endowed with family connections and economic independence.16

Northeastern Massachusetts had been exporting shoes since before the Revolution, for it possessed the prerequisites of cottage shoemaking in abundance: it was poor and overcrowded, many of its farmers had taken to raising cattle (and thus leather) on their worn-out land, and there was access to markets through Boston and the port towns of Essex County. After the Revolution, thousands of farm families turned to the making of shoes, for footwear was protected under the first national tariffs, the maritime economy on which the shoe trade depended was expanding, and they were still poor.

The rural shoemakers’ shops were not entrepreneurial ventures. Neither, if we listen to the complaints of merchants and skilled artisans about “slop work” coming out of the countryside, were they likely sources of craft traditions or occupational pride. They were simply the means by which farmers on small plots of worn-out land maintained their independence.17

The journal of James Weston, a shoemaker in Reading during these years, suggests something of the rural shoemaker’s way of life. Weston was first and last a farmer. He spent his time worrying about the weather, working his farm, repairing his house and

outbuildings, and sharing farm labor with his neighbors and kinfolk. He went hunting with his brothers-in-law, took frequent fishing trips on the coast at Lynn, and made an endless round of social calls in the neighborhood. The little shop at the back of Weston’s house supplemented his earnings, and he spent extended periods of time there only during the winter months. With his bags of finished shoes he went regularly to Boston, often in the company of other Reading shoemakers. The larger merchants did not yet dominate the trade in country shoes, and Weston and his neighbors went from buyer to buyer bargaining as a group, and came home with enough money to buy leather, pay debts and taxes, and survive as independent proprietors for another year. Weston enjoyed relations of neighborly cooperation with other men and he was the head of a self-supporting household and an equal participant in neighborhood affairs. In eighteenth-century Massachusetts, these attributes constituted the social definition of adult manhood. Mayo Greenleaf Patch received that status as a wedding present.18

Greenleaf and Abigail occupied the new house and shop early in 1790, and their tax assessments over the next few years reveal a rise from poverty to self-sufficiency or perhaps a little more. In 1790, for the first time, Greenleaf paid the tax on a small plot of land—land that he did not own. Two years later, his personal property had increased enough to rank him 56th among the 122 taxpayers in the North Parish. He wasn’t getting rich, but he enjoyed a subsistence and a place in the economy of his neighborhood. That alone was a remarkable achievement for a young stranger who had come to town with almost nothing.19

With marriage and proprietorship came authority over a complex and growing household. Few rural shoemakers in the 1790s continued to work alone. They hired outside help, and they put their wives and children to work binding shoes. Isaac Weston brought in apprentices and journeymen, and Greenleaf Patch seems to have done the same. In 1790 the Patch family included

Greenleaf and Abigail and their infant daughter, along with a boy under the age of sixteen and an unidentified adult man. In 1792 Patch paid the tax on two polls, which suggests again that the household included an adult male dependent. It seems clear that he hired outsiders and that he regularly headed a household work team that (assuming Abigail helped) numbered at least four persons.20

During those same years, Greenleaf Patch enjoyed the trust of the McIntires and their neighbors. When Archelaus McIntire died in 1791, Patch was named executor of his estate. Greenleaf spent considerable effort, including two successful appearances in court, putting his father-in-law’s affairs in order. In 1794 he witnessed a land transaction involving his brother-in-law, suggesting again that he was a trusted member of the McIntire family. That trust was shared by the neighbors. In 1793 the town built a schoolhouse near the Patch home, and in 1794 and 1795 the parish paid Greenleaf Patch for boarding the schoolmistress and for escorting her home at the end of the term. Those were duties that could only have gone to a trusted neighbor who ran an orderly house.21

Greenleaf Patch had found a home. But his gains were precarious, for they rested on his ties to the McIntires and on the use of land that belonged to them. When Archelaus died in 1791 and Patch was appointed executor of the estate, title to the McIntire properties fell to nineteen-year-old son Archelaus Jr., who was bound out to a guardian. At that point Greenleaf began to prey on the resources of Abigail’s family. In succeeding years bad luck and moral failings would cost him everything he had gained.22

With Archelaus McIntire dead and his son shipped off to a guardian, the McIntire household shrank to two women: his widow and his daughter Deborah. The widow described herself as an invalid, and there may have been something wrong with

Deborah as well. In his will Archelaus ordered that his son take care of Deborah. Archelaus Jr. would repeat that order ten years later, when Deborah, still unmarried and still living at home, was thirty-five years old. It was a vulnerable household, and it became a target of Mayo Greenleaf Patch. Soon after Archelaus McIntire’s death (and shortly before Patch was to inventory the estate), the widow complained to authorities that “considerable of my household goods & furniture have been given to my children,” and begged that she be spared “whatever household furniture that may be left which is but a bare sufficiency to keep household.” Since two of her four daughters were dead and Deborah lived with her, and since her only son was under the care of a guardian, the “children” could have been none other than Abigail and Greenleaf Patch, whose personal property taxes mysteriously doubled between 1791 and 1792.23

Patch followed this with a second and more treacherous assault on the McIntires and their resources. In November 1793 Archelaus McIntire, Jr., came of age and assumed control of the estate. Greenleaf’s use of McIntire land no longer rested on his relationship with his father-in-law or on his role as executor, but on the whim of Archelaus Jr. Patch took steps that would tie him closely to young Archelaus and his land. Those steps involved a woman named Nancy Barker, who moved into North Reading sometime in 1795.

Mrs. Barker had been widowed twice—most recently, it seems, by a Haverhill shoemaker who left her with his tools and scraps of leather, a few valueless sticks of furniture, and two small children. Nancy Barker was the half sister of Mayo Greenleaf Patch, and in November 1795 she married Archelaus McIntire, Jr. She was thirty-one years old. He had turned twenty-three the previous day, and his marriage was not a matter of choice: Nancy was four months pregnant.24

Archelaus and Nancy were an unlikely couple, and we must ask how the match came about. If we note that Archelaus had

grown up with three older sisters and no brothers, his attraction and/or vulnerability to a woman nearly nine years his senior becomes a little less mysterious. And Nancy had good reasons for being attracted to him: she was a destitute widow with two children, and he was young, perhaps manipulable, unmarried, and the owner of substantial property. Finally, Greenleaf Patch, who was the only known link between the two, had a vital interest in creating ties between himself and his in-laws’ land. It is plausible (indeed, it seems inescapable) to conclude that Nancy Barker, perhaps in collusion with her half brother, seduced Archelaus McIntire, Jr., and forced a marriage. (Given how many young people experienced premarital sex, and how many of them faced propertyless futures, it would be surprising if some of them did not realize that they could acquire property or the use of it through seduction and the hurried marriages that often followed. Indeed, Greenleaf Patch’s marriage to Abigail McIntire may not have been a case of bad luck turning to good, but a calculated strategy vis-à-vis seventeen-year-old Abigail and her family.)

Of course that may be nothing more than perverse speculation. It is possible that Nancy and Archelaus simply fell in love, started a baby, and got married, and that whatever role Greenleaf Patch played in the affair only added to his esteem among the McIntires and in the neighborhood. But that line of reasoning must confront an unhappy fact: the neighbors and the McIntires began to dislike Mayo Greenleaf Patch.

The first sign of trouble came in autumn of 1795, when town officials stepped into a boundary dispute between Patch and Deacon John Swain. Massachusetts towns encouraged neighbors to settle arguments among themselves. In all three parishes of Reading in the 1790s only three disagreements over boundaries came before the town government, and one of those was settled informally. Thus Greenleaf Patch was party to one of the two mediated boundary disputes in Reading in the 1790s. Then, after 1795, the schoolmistresses no longer stayed in the Patch household;

they now boarded with his unfriendly neighbor Deacon Swain. In 1797 Patch complained that he had been overtaxed (another rare occurrence), demanded a reassessment, and was in fact reimbursed. Then he started going to court. In 1798 Greenleaf Patch sued Thomas Tuttle for nonpayment of a debt and was awarded nearly $100 when Tuttle failed to appear. A few months earlier, Patch had been hauled into court by William Herrick, a carpenter who claimed that Patch owed him $480. Patch denied the charge and hired a lawyer, and the court found in his favor. But Herrick appealed the case, and a higher court awarded him $100.52. Six years later, Patch’s lawyer was still trying to collect his fee.25

There was also a question about land. In the dispute with John Swain, Greenleaf Patch was described as the “tenant” of a farm that does not match any of the properties described in the McIntires’ deeds. A federal tax list demonstrates that Patch did not occupy any of his brother-in-law’s land in 1798. It seems that, perhaps as early as 1795, Greenleaf Patch had been evicted from McIntire land.26

At some point the authorities had stopped trusting Greenleaf Patch, and by 1801 they made it clear. A year after Nancy Barker McIntire died in 1798, Archelaus remarried, then died suddenly himself in 1801. He willed his estate—two houses and the ninety-seven-acre farm, sixty more acres of upland and meadow in North Reading, and fifteen acres in the neighboring town of Lynnfield—to his children by Nancy Barker. Archelaus’s second wife sold her right of dower and left town, and the property fell to girls who were four and five years of age. Their guardian would have use of the estate for many years. Abigail and Greenleaf Patch were the orphans’ closest living relatives, and though they had moved away by this time surely authorities knew their whereabouts. Yet the officials passed them over and appointed William Whitridge, a cooper in North Reading, as legal guardian. For Patch it was a costly decision: it finally cut him off from property

that he had occupied and plotted against for many years. The promising family man of the early 1790s was, apparently, a contentious and morally bankrupt outcast by 1798.27

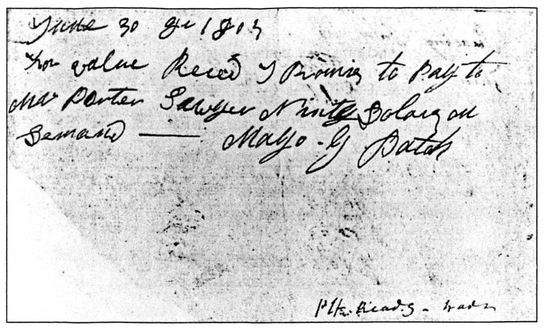

Mayo G. Patch I.O.U. (Sawyer v. Patch, Essex County Court of Common Pleas, March 1803, Essex Institute, Salem, Mass.)

Late in 1799 Greenleaf and Abigail and their four children—including the newborn Sam Patch—left North Reading and resettled in Danvers. Famous as the hometown of the witchcraft hysteria of 1692, Danvers in 1800 was a neighborhood of farmer-shoemakers on the outskirts of Salem. We cannot know why the Patches selected that town. Greenleaf’s father may have lived there briefly around 1780, but Abigail Patch’s ties to the town were stronger. Danvers was her mother’s birthplace, and she had an aunt and uncle, five first cousins, and innumerable distant kin in the town. Also, her father had owned land in Danvers. In 1785 Archelaus McIntire, Sr., had seized seven acres from John Felton, one of his in-laws, in payment for a debt. Archelaus Jr. sold the land back to the Feltons in 1794 but did not record the transaction

until 1799. Possibly he agreed to allow Greenleaf Patch to use that land—an agreement that would have gotten rid of Greenleaf and provided for his sister at the same time. (Another speculation involves the troubled sister, Deborah. She disappeared from records in Reading after being mentioned as a dependent in her brother’s will in 1801. Perhaps she was passed on to the Patches in Danvers, a possibility raised by the fact that a woman named Debbie McIntire hanged herself in Danvers in December 1801.)28

Danvers was another shoemaking town, and the Patches probably rented a farm and made shoes. They were in any case poor, obscure, and temporary residents of the town. Their names do not appear in the records of town government; late in 1799 the Danvers tax collector assessed Greenleaf for a poll tax and nothing else (no real estate, no personal property). In a census taken at about the same time, the Patch household included Greenleaf and Abigail, their children, and no one else, which suggests that they no longer hired help. But this, like everything else about the family’s career in Danvers, rests on guesswork. We know only that they lived there.29

Late in 1802 Greenleaf Patch received a reprieve. His half brother Job Davis (his mother’s son by her first marriage, and the brother of Nancy Barker) died in the fishing village of Marblehead and left Patch one-fifth of his estate. The full property included a butcher’s shop at the edge of town, an unfinished new house, and what was described as a “mansion house” that needed repairs. The property was mortgaged to merchants named William and Benjamin T. Reid, and the heirs inherited the mortgage along with the estate.30

The other heirs sold to the Reids, but Greenleaf Patch, whether from demented ambition or lack of alternatives, moved his family to Marblehead early in 1803. He finished the new house, moved into it, and reopened the shop. In 1804 he was assessed a poll tax and listed as the resident of the house and shop

and the owner of a horse and two pigs. At least on paper, Greenleaf Patch was back in business.31

But it was a shaky business—founded on property that Greenleaf did not truly own and burdened by debt. Some of the debts were old. Patch owed Ebenezer Goodale of Danvers $54. He also owed Porter Sawyer of Reading $92 (and paid a part of it by laboring at 75 cents a day). Then there were debts incurred in Marblehead: $70 to the widow Sarah Dolebar; a few dollars for building materials and furnishings bought from the Reids; $50 to a farmer named Benjamin Burnham; $33 to Zachariah King of Danvers; $35 to Joseph Holt of Reading; another $35 to Caleb Totman of Hampshire County. Finally, there was the original mortgage held by the Reids. Greenleaf Patch’s renewed dreams of independence collapsed under the weight of these debts. In March 1803 a creditor repossessed property valued at $150. A few weeks before Christmas of that year the sheriff seized the new house. In the following spring, Patch missed a mortgage payment and the Reids took him to court, seized the remaining property, and sold it at auction. Still, Patch retained the right to reclaim it by paying his debts. The story ends early in 1805, when the Reids bought Greenleaf Patch’s right of redemption for $60. Patch had struggled with the Marblehead property for two years, and it had come to nothing.32

With that, the Patches exhausted the family connections on which they had subsisted since their marriage. The long stay in North Reading and the moves to Danvers and Marblehead had been determined by the availability of relatives and their resources. In 1807 the Patches moved to the mill village of Pawtucket, Rhode Island, nearly one hundred miles south of the neighborhoods in which the Patches and McIntires had always lived. The move was the climactic moment in their history: it marked their passage out of the family economy and into the labor market.

New England families did not move into Pawtucket’s mills

unless something bad had happened—usually to the man of the house. A broken Mayo Greenleaf Patch fit that pattern perfectly. Pawtucket was enjoying a small boom in 1807, and if Greenleaf had been willing and physically able he could have found work. But we know that he did not work in Pawtucket. He drank, he stole the money earned by Abigail and the children, and he threatened them frequently with violence. Then, in 1812, he abandoned them. Abigail waited six years and divorced him in 1818. To the court she recounted Greenleaf’s drinking and his threats and his refusal to work, then revealed what for her was the determining blow: Mayo Greenleaf Patch had drifted back to Massachusetts and had been caught trying to pass counterfeit money. In February 1817 he had been sent to the Massachusetts State Prison at Charlestown. He was released in August 1818—at the age of fifty-two—and that is the last we hear of him.33

The invitation to move to Pawtucket may have come from the mill owner Samuel Slater himself, who was searching far beyond Pawtucket for child workers, recruiting among the urban and rural poor. The seaports and old farming towns of northeastern Massachusetts produced such persons in abundance, and as early as 1797 one of Slater’s partners reported Marblehead as a particularly likely spot: “ … the inhabitants appear to be very Poor their Houses very much on the decline—I apprehend it might be a good place for a Cotton Manufactory Children appearing very Plenty.” Slater may have recruited the Patch family on one of his periodic trips to Salem and Marblehead.34

Pawtucket was something new in America: a town where women and children supported men or lived without them, and where women reconstructed lives that had been damaged in the failure of their men. Abigail Patch was one of those women, and her grim work of reconstruction coincided with the childhood and youth of her son Sam.

Independence—along with its burdens, dangers, and opportunities—was something that Abigail Patch had never expected. She had grown up in a family that, judging from available evidence, was a model of eighteenth-century rural patriarchy. Her father possessed a respected family name and a farm inherited from his father that he passed on to his son; he was the steward of the family’s past and future as well as its present provider. As a McIntire, he conferred status on every member of his household. As a voter, he spoke for the family in town affairs; as a father and church member, he led them in daily prayer; and as a proprietor, he made decisions about the allocation of family resources, handled relations with outsiders, and performed most of the heavy work.

Archelaus McIntire had married Abigail Felton of Danvers and had brought her to a town where she lived apart from her own family but surrounded by Mclntires; her status in North Reading derived from her husband’s family and not her own. She and her daughters spent long days cooking and cleaning, gardening, tending and milking cows, making cloth and clothing, and caring for the younger children—work that took place in and near the house and not on the farm. And while that work was essential, New England men assumed that it would be done and placed no special importance on it. The notion of a separate and cherished domestic sphere was slow to catch on in the countryside and, if we may judge from the spending patterns of the McIntires, it was absent from their house. Archelaus McIntire spent his money on implements of work and male sociability—horses, wagons, well-made cider barrels, a rifle—and not on the china, tea sets, and feather beds that were appearing in towns and among the rural well-to-do. The McIntires owned a solid table and a Bible and a few other books, and there was a clock and a set of glassware as well. But the most imposing piece of furniture in the house was Archelaus’s desk. Insofar as the McIntire children had any quiet evenings at home, they probably

spent them listening to the father read his Bible (the mother was illiterate) or keeping quiet while he figured his accounts.35

Abigail Patch signature (Petition of Abigail Patch for Divorce, Records of the Supreme Court of Providence County, Providence College Archives)

As the fourth and youngest daughter, Abigail traded work and quiet subordination for security, for the status that went with being a female McIntire, perhaps even for peace and affection in the home. And as she set up house with Mayo Greenleaf Patch, it is unlikely that she expected things to change. Years later Abigail recalled that in taking a husband she expected not a partner but “a friend and protector.” She spoke of her “duties,” and claimed to have been an “attentive and affectionate wife.” It was the arrangement that she had learned as a child: husbands supported their wives and protected them; wives worked and were attentive to their husbands’ needs and wishes. All available evidence suggests that those rules governed the Patch household during the years in North Reading.36

Abigail and Greenleaf Patch maintained neither the way of life nor the living standards necessary for the creation of a private, domestic world in which Abigail could have exercised independent authority. The house was small and there was little money, and the household regularly included people from outside the immediate family—Greenleaf’s apprentices and journeymen,

the schoolmistresses, and probably Nancy Barker and her two children.

At work, rural shoemakers maintained a rigid division of labor based on sex and age, and Greenleaf’s authority as a father and master craftsman affected every corner of Abigail’s life. Abigail’s kitchen, if indeed it was a separate room, was a busy place. It was there that she bound shoes as a semiskilled and subordinate member of her husband’s work team, cared for the children (she gave birth five times between 1789 and 1799), did the cooking, cleaning, and laundry for a large household, and stared across the table at apprentices and journeymen who symbolized her own drudgery and her husband’s authority at the same time. As Abigail Patch endured her hectic and exhausting days, she may have dreamed of wallpapered parlors and privacy and quiet nights by the fire with her husband. But she must have known that such things were for others and not for her. They had played little role in her father’s house, and they were totally absent from her own.37

Greenleaf Patch, despite (or perhaps because of) his meager resources, consistently made family decisions—not just the economic choices that were indisputably his to make, but decisions that shaped the texture and feeling of life within the family.

Take the naming of children. Since the beginnings of settlement, New Englanders reinforced their corporate sense of family by naming children for their parents, grandparents, and other close relatives. As Greenleaf Patch was separated from his own family and dependent on McIntire resources, when children came along we might expect him and Abigail to have honored McIntire relatives. That is not what happened. The first Patch child—the one conceived before the wedding—was a daughter born in 1789. She was named Molly, after a daughter of Greenleaf’s brother Isaac. A son came two years later, and the Patches named him Greenleaf. Another daughter, born in 1794, was given the name Nabby, after another of Isaac Patch’s daughters.

A second son, born in 1798, was named for Isaac’s son Samuel (or perhaps Isaac’s and Greenleaf’s brother Samuel, who worked the farm next to Isaac’s). When that child died, the son born the following year—the daredevil Sam Patch—was also named Samuel. (The practice of giving a dead child’s name to the next-born child of the same sex was a marker of customs that valued the family over the individual identity of the child, and it was falling into disuse in the eighteenth century. That Greenleaf Patch persisted in this practice at the turn of the nineteenth century suggests a firm, die-hard traditionalism on his part.) The last child, a boy born in Marblehead in 1803, was named for Greenleaf’s brother Isaac. All the children’s names came from the little world in Wenham—uncle Samuel’s nine-acre farm, the shared barn and outbuildings, and the eighteen acres operated by brother Isaac—where Greenleaf Patch had presumably spent much of his childhood. 38

Religion is a second and more important sphere in which Greenleaf seems to have made choices for the family. Abigail McIntire had grown up in a religious household. Her father had joined the North Parish Congregational Church a few days after the birth of his first child in 1762. Her mother had followed two months later, and the couple baptized each of their five children. The children in their turn became churchgoers. Abigail’s sisters Mary and Mehitable joined churches, and her brother Archelaus Jr. expressed a strong interest in religion as well. Among Abigail’s parents and siblings, only the questionable Deborah left no religious traces.39

Churchgoing traditions in the Patch family were not as strong. Greenleaf’s father and his first wife joined the Congregational church in Wenham during the sixth year of their marriage in 1736, but the family’s ties to religion weakened after that. Timothy Patch, Jr., did not baptize any of his thirteen children, neither the ten presented him by his first wife nor the three born to Thomasine Greenleaf Davis, the nonchurchgoing widow whom he married

in 1759. None of Greenleaf’s brothers or sisters became full members of the church, and only his oldest brother, Andrew, “owned the covenant”—a practice permitting adult children of church members to place their own families under the church’s watch and governance without themselves becoming members.40

Among the Wenham Patches, however, there remained pockets of religiosity, and they centered, perhaps significantly, in the homes of Greenleaf’s brother Isaac and his uncle Samuel. Uncle Samuel was a communicant of the church, and although Isaac had no formal religious ties, he married a woman who owned the covenant. The churchgoing tradition that Greenleaf Patch carried into marriage was ambiguous, but it almost certainly was weaker than that carried by his wife. And from his actions as an adult, we may assume that Greenleaf was not a man who would have been drawn to the religious life.

As Greenleaf and Abigail married and had children, the question of religion could not have been overlooked. The family lived near the church in which Abigail had been baptized and in which her family and her old friends spent Sunday mornings. As the wife of Greenleaf Patch, Abigail had three options: she could lead her husband into the church; she could, as many women did, join the church without her husband and take her children with her; or she could break with the church and spend Sundays with an irreligious husband. The first two choices would assert Abigail’s authority and independent rights within the family. The third would be a capitulation, and it would have painful results. It would cut her off from the religious community into which she had been born, and it would remove her young family from religious influence.

The Patches lived in North Reading for twelve years and had five children in that town. Neither Greenleaf nor Abigail joined the church, and none of the babies was baptized. We cannot retrieve the actions and feelings that produced those facts, but this much is certain: in the crucial area of religious practice, the

Patch family bore the stamp of Greenleaf Patch and not of Abigail McIntire. When Greenleaf and Abigail named a baby or chose whether to join a church or baptize a child, the decisions extended his family’s history and not hers.41

Abigail accepted her husband’s dominance in family affairs throughout the years in North Reading, years in which he played, however ineptly and dishonestly, his role as “friend and protector.” With Greenleaf’s final separation from the family economy and his humiliating failure in Marblehead, Abigail began to impose her will upon domestic decisions. The result, within a few years, was a full-scale feminine takeover of the family.

In 1803 Abigail gave birth to her sixth child in Marblehead, a boy named Isaac. She was still a relatively youthful thirty-three, and Isaac, perhaps significantly, would be her last child. Isaac was baptized at the Second Congregational Church in Marblehead, though neither of his parents was a member. And in April 1807 Abigail and her oldest daughter, Molly, presented themselves for baptism at the First Baptist Church in Pawtucket. By then Abigail was thirty-seven, had been married nineteen years, and had five living children. Molly was eighteen and unmarried. Neither followed the customs of the McIntire and Patch families, where women who joined churches did so within a few years of marriage. Abigail and Molly Patch presented themselves for baptism not because they had reached predictable points in their life cycles but because they had decided to join a church.42

At the same time Abigail’s daughters appear to have dropped their given names and evolved new ones drawn from their mother’s and not their father’s side of the family. Molly joined the church as Polly Patch. Two years later this same woman married under the name Mary Patch. (Abigail’s oldest sister, who had died in the year that Abigail married Greenleaf Patch, had been named Mary.) The second Patch daughter, Nabby, joined the First Baptist Church in 1811, but by then she was calling herself Abby. By 1829 she was known as Abigail. The daughters of Abigail

Patch, it seems, were affiliating with their mother and severing symbolic ties with their father, and they were doing so while Greenleaf remained in the house.43

For five years Abigail worked and took the children to church while her husband drank, stole her money, and issued sullen threats. He ran off in 1812, and by 1820 Abigail, now officially head of the household, had rented a house and was taking in boarders. Over the next few years the Patch sons left home: Sam for New Jersey, Isaac for Illinois, Greenleaf for parts unknown. Among the Patch children, only Mary (Molly, Polly) stayed in Pawtucket. Her husband died in 1817, leaving her with two small children and pregnant with another. In 1825 the widowed Mary was caught sleeping with a married man and was expelled from her church. Two years later—as the result of an extended affair, or perhaps of a new one—Mary gave birth to a child out of wedlock. Sometime before 1830 Abigail closed the boardinghouse and moved into a little house on Main Street with Mary and her four children. Abigail and her daughter and granddaughters were to live in that house for the next twenty-five years.44

The neighbors remembered Abigail Patch as a quiet, steady little woman who went to the Baptist church. She did so with all the Patch women and none of the Patch men. Mary had joined with her, and Mary’s daughters followed in their turn: Mary and Sarah Anne in 1829, Emily (the illegitimate girl born in 1827) in 1841. First Baptist was a Calvinist church, subsidized and governed by the owners of Pawtucket’s mills. The Articles of the Church insisted that most of humankind was hopelessly damned, that God chose only a few for eternal life and had in fact chosen them before the beginning of time, that “the heart is deceitful &c., and that the carnal mind is enmity against God, not subject to his law &c. And that in the flesh dwelleth no good thing.” It was not a cheerful message. But it struck home among the Patch women—and perhaps among the other Pawtucket women who filled three-fourths of the seats on Sunday mornings.45

The Patch women spent most of their time in the house on Main Street. Abigail bought the house in 1842 (it was the first piece of real estate that the Patches had ever owned), and her granddaughters Mary and Emily taught school in the front room for many years. The household was self-supporting, and the women’s relationships with men were either troubled or nonexistent. Abigail’s daughter and the granddaughters she helped to raise either avoided men or got into trouble when they did not. Abigail never remarried. Mary also remained single for the rest of her life. Sarah Anne Jones, Mary’s second daughter, was thirtysix years old and unmarried when called before a church committee in 1853. Although she married a man named Kelley during the investigation, she (like her mother) was excommunicated “because she has given this church reason to believe she is licentious.” Sarah Anne’s sisters, the schoolteachers Mary and Emily, were spinsters all their lives. Abigail Patch lived on Main Street with the other women until 1854, when she died, after a long and apparently trying illness, at the age of eighty-four.46

The women lived quietly and simply (Abigail’s furniture and other belongings were valued at only $17 at her death) but with as much outward respectability as they could muster. Their pupils remembered Abigail’s granddaughters with affection; Reverend Benedict recalled that Abigail was “of a most respectable character,” and that the other Patches (despite the two dismissals from Benedict’s church) were “of good reputation.” Behind the parlor schoolroom and the kindly cover-ups, however, was a backroom world inhabited only by the Patch women. Within that world, Abigail and her daughter Mary reconstructed not only themselves but the history of their family.47

Toward the end of the nineteenth century, a Providence newspaperman decided to write about the mill worker-hero Sam Patch. He asked Emily Jones, Abigail’s youngest granddaughter, about the Patch family history. Emily, born in 1827, knew about the family’s past only through what she had picked up from her

mother and grandmother. Her response to the reporter revealed the attempts at discretion and the selective amnesia with which any family remembers its past. In the case of the Patch family, however, the fabrications were sadly revealing.48

Miss Jones told the reporter nothing about what the Patch women did for a living, nothing of their religious or personal lives, certainly nothing about the promiscuity of her mother and sister or of her own illegitimate birth. Instead she recounted the public lives of the Patch men. Emily claimed that her oldest uncle, Greenleaf Patch, Jr., had gone off to Salem to become a lawyer. That is not true: no one named Greenleaf Patch was ever licensed to practice law in Massachusetts. About her uncle Sam Patch, Emily said that in the 1820s he operated a spinning mill of his own north of Pawtucket, but failed when his partner ran off with the funds. This is possible, but there is no evidence that it happened. What we do know about Sam Patch is that he was a drunkard with a powerful suicidal drive who succeeded in killing himself at the age of thirty. Miss Jones remembered that her youngest uncle, Isaac, moved to Illinois and became a farmer—another piece of family knowledge that cannot be verified. It seems that Abigail Patch and Mary Patch Jones embellished the careers of their men, giving them a respectability they may not have had. It may have been a way of erasing some of the pain created by Mayo Greenleaf Patch.49

Emily’s memory of her grandfather upholds that suspicion. We know that Greenleaf moved to Pawtucket, headed the household in 1810, and stayed until 1812. But Miss Jones told the reporter that her grandfather had been a farmer in Massachusetts, and that he died before Abigail brought her children to Pawtucket. 50

In the 1820s, when Sam Patch was a famous jumper, he did not talk about his family. He told one young friend that he had been

born in Pawtucket and then orphaned, another that he had been a sailor. A girl who knew him thought that he was a foreigner, and a newsman in Providence did not even know that Sam Patch was from neighboring Pawtucket. Sam burst into public consciousness as the Jersey Jumper, the man who leaped waterfalls in the newspapers. He was a nineteenth-century hero: no past, no family connections, no firm ties to any place. It was what the public was learning to expect, and it may have been what Sam Patch wanted.51

There was not much family history worth remembering. Sam Patch spent his childhood in the wreckage that his father had made. He could not remember North Reading (notation of Sam’s birth was the final record of the Patches in that town), and it is unlikely that he ever saw his father treated with neighborliness or respect. He knew him only as a broken man who made the house smell of alcohol, a man whose despairing silences could explode into incomprehensible and terrifying violence. When Sam was thirteen, the father abandoned him forever. In his twenties, Sam Patch was described as melancholy, verging on morose. He may have retreated into himself at an early age. He was also a heavy drinker, and that too may have begun early on. Drunkenness and melancholy: these were what Greenleaf Patch finally possessed, and what he passed on to his second son.

Sam’s mother knew that children were supposed to work and obey. She was trying to keep a family together without a husband, and she counted on the money her children could earn in Pawtucket. She found jobs for them, and she doubtless took them to church and enrolled them in Sunday school. We have reason to believe that Sam Patch was not a good boy, and he probably did not pay much attention to Reverend Benedict’s half-comprehensible threats about predestination, limited atonement, and human inability. At Sunday school, the teachers tried to explain: Sam was bad and could do nothing to make himself good. They taught reading from the King James Bible, then set

the children to memorizing Bible verses—a pedagogical form that taught obedience and rote memory, not imagination and individual moral development. After a week in the mills and Sundays listening to Reverend Benedict and his teachers, the child Sam Patch returned to Abigail’s life of work and prayer, and to her hardening insistence that much of the family’s history had never happened. We do not know how Sam held up under all this. But we do know that he rejected it. Reverend Benedict tells us that “Sam Patch’s course of life [was] a source of deep affliction to his mother … .”52

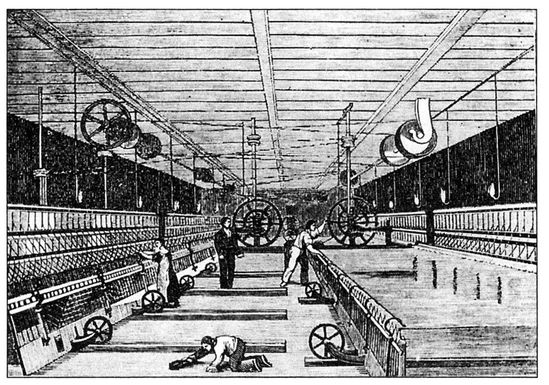

Sam went to work at Samuel Slater’s White Mill at the age of seven or eight. The White Mill, completed in 1799 on a site directly across the river from Slater’s first mill, was small and unpretentious like its predecessor. (The original floor space was only forty by twenty-six feet; in 1808 it was expanded to seventy-six by twenty-nine feet.) The wooden structure was two stories high, and, unlike the brick behemoths that mill owners would begin building in the 1820s, it blended into the neighborhood. Painted white and topped with a cupola, to the child Sam Patch the White Mill might have looked like the First Baptist Church.53

Inside, the mill was full of children. In the ground-floor carding room scores of boys and girls worked under an overseer. They were given raw cotton that other children, working in their homes, had cleansed of dirt and twigs, and fed it into carding machines with revolving wire teeth that combed it until the fibers lay parallel. The carding machines turned raw cotton into loose cotton ropes. More children tended roving machines that twisted and stretched the cotton into longer and tighter ropes called roves, then ran the roves upstairs to the spinning room. There skilled men worked the spinning mules, with the help of children called piecers and scavengers. Scavengers (the smaller children were best at this) crawled between the carriage and frame and

under the long lines of thread, cleaning the floor and machinery and picking lint and dust balls off the threads. Piecers stood outside the frame and knotted broken threads at the end of a run, tying at a rate of five or six knots a minute.54

The millwork that Sam and the other children did was neither dangerous nor particularly difficult. True, Reverend Benedict reported that some of the children “had their hands terribly lacerated” by the carding machines, and none but the most nimble scavengers avoided blows from the moving parts of the machinery. But there are—apart from Benedict’s—few accounts of injuries to the children. As for factory discipline, it was by contemporary standards neither brutal nor cruel. Samuel Slater himself frequently roamed the carding room, exerting what an admirer called “a strict, though mild and paternal scrutiny” over the children, and boss spinners sometimes backed up their commands with slaps and ear boxings. (A child who later worked under the boss spinner Sam Patch recalled—with no hint of resentment—that “many a time he gave me a cuff over the ears.”) But routine discipline in the mill consisted of threats, humiliation, and occasional praise. The mills, after all, were in business to produce cotton yarn, not to brutalize children. While yarn was produced to the mill owners’ and the spinners’ satisfaction, Sam and his young workmates were relatively safe.55

The children’s chief complaint was not injury or brutality but the deadening monotony of simple, attention-demanding tasks synchronized with machines that ran twelve hours a day. The rooms were cold in winter and hot and humid in summer, the air was filled with cotton dust, and the factories were among the noisiest places that men had ever made. A Boston gentleman who visited Pawtucket in 1801 and peered into a room full of child workers felt “pity for these poor creatures, plying in a contracted room, among flyers and coggs, at an age when nature requires for them air, space, and sports. There was a dull dejection in the countenances of all of them. This, united with the deafening

roar of the falls and the rattling of the machinery,” made it a very unpleasant place. Mill children suffered from swollen ankles and loss of appetite, and they were tired all the time. Whenever the machines stopped, youngsters crawled into corners and fell asleep. At the end of the day many dragged themselves home, went to bed without supper, and awoke only to return to work. In the mills, slaps and cuffings were used most often to keep drowsing children awake.56

Sam Patch spent his childhood and youth in the mills, picking lint and tying knots amid the din of machinery and falling water, passing whole days in a half-sleep punctuated by shouts and occasional slaps across the head. He seems to have been good at it: he learned the rules and skills of the spinning room, and in the 1820s he took his place as one of the first American-born boss spinners.

The boss spinners were a remarkable set of men. The spinning mule was among the biggest machines in the world, and it had revolutionized the making of cotton cloth. Yet before the introduction of the self-acting mule in the 1840s, mule spinning was only partly automated, and none but skilled, experienced men operated the machines. With each cycle of the spinning mule a long; heavy carriage rode out on tracks from the machine, stretching and twisting the carded and roved cotton into yarn (what we call thread). The carriage then reversed, and the finished thread wound onto bobbins attached to the machine. It was at this final stage that the boss spinner’s skills became crucial. With one hand he depressed a wire that ran the length of the carriage, holding the threads tight and flat. With the other hand he grasped a wheel that pushed the carriage and adjusted its speed, and with his knee he muscled the carriage toward the bobbins, carefully controlling the speed and keeping a lookout along the line of threads. The work required experience, along with a practiced mix of strength and a sensitive touch: return the carriage too slowly and the power-driven bobbins would snap the threads;

push it too quickly and the threads tangled. “The skill and tact required in the operator,” said an English observer of the process, “deserve no little admiration, and are well entitled to the most liberal recompense.”57

Mule spinning (from George S. White, comp., Memoir of Samuel Slater, Philadelphia, 1836, author’s collection)

Before 1820 most spinners in New England mills were emigrants from the factory towns of Lancashire. They were veterans who knew that their skills were essential, and they commanded respect. Slater and the other proprietors may have owned the spinning mules, but the spinners were semi-independent subcontractors: they worked for piece rates, and it was they who hired, trained, paid, and disciplined their own helpers. (An illustration in a book praising Samuel Slater places a well-dressed supervisor behind the spinner, but in fact such men were either ineffective or absent.) Each spinner adjusted the machine to his own body and pace of work; when a spinner had labored with a mule for a few weeks, no one else could run it—a partnership between

man and machine that made the man irreplaceable. Pawtucket’s mule spinners earned as much as the overseers downstairs, and much more than the repair mechanics, clerks, and other men who worked in and around the mills. The owners sometimes branded the mule spinners as arrogant, selfimportant, and often drunken and riotous. They may have been all that, but first and last the spinners were fiercely independent—skilled, formidable artisans who had constructed a craftsman’s world within factory walls.58

We can imagine why the child Sam Patch did well in the spinning room. There, at least, work and discipline were tied to understandable rules enforced by predictable authorities. If Sam showed up on time, stayed awake, and attended to his tasks, he avoided humiliation and occasionally won a bit of praise. He may have seen being a boss spinner as a good alternative to the brute impossibilities of the rest of his life. The spinners made what looked like good money, they exerted a fatherly authority that Sam did not know at home, and they commanded respect in the mills and in the neighborhood. For their part, the English mule spinners may have recognized Sam as an able boy (and perhaps as a boy who needed help) and trained him up as one of their own. Sam worked hard, paid attention, and became one of them.

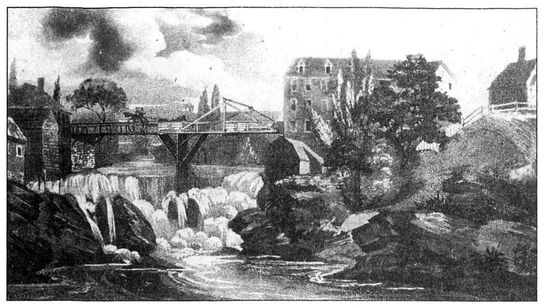

The falls of the Blackstone River provided a second way out of Sam’s closed world. Travelers on the road between Providence and Boston often paused to look at Pawtucket Falls, for the white water cascading fifty feet over broken black rocks was a stirring sight. “Romantic,” granted Timothy Dwight, president of Yale College. An Englishwoman deemed it “a very respectable fall,” while a young American romantic pronounced it “a scene of astonishing beauty and sublimity.” “It is a circumstance rather unusual,” he continued, “that an object of such wild grandeur, should be environed in the midst of dwelling houses, and the cotton

establishments which the higher surface of the water supplies.” 59

Samuel Slater and the others who built Pawtucket’s factories had little use for the “wild grandeur” of their waterfall. Their mill dams and raceways diminished the falls, flooded farmland upriver from them, and damaged a valuable fishing ground, and they fought legal battles with their neighbors over their right to do that. When the manufacturers mentioned the river and falls, they talked of millsites and the volume of water and the possibilities of flooding, not of its beauty. They wanted to tame the waterfall and make it useful, and when they built a village upstream from it the buildings had the effect of diminishing the falls and then hiding them from view. By 1820 mills, workshops, houses, and fences built to keep livestock from falling into the river blocked the view of the river and falls from nearly every point in Pawtucket. Sam Patch could have passed through this densely built townscape without seeing the waterfall at its center.

A short walk through crooked streets filled with lumber, cotton bales, and foraging pigs and dogs brought Sam to the White Mill. From the windows of the spinning room upstairs he could look directly onto the Blackstone River above the falls. From that viewpoint it was Samuel Slater’s river: the mill dam crossed the river a few yards upstream from Sam’s window, and at the end of the dam on the far side was Slater’s first mill, its machines and busy children visible through the windows. Sam’s eyes could follow the river downstream to where it passed under a sturdy wooden bridge and disappeared from sight.60

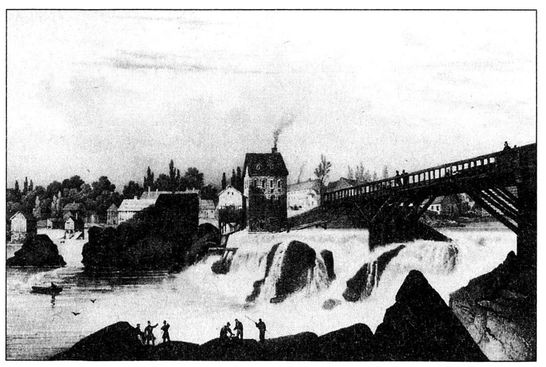

The centerpiece of Samuel Slater’s Pawtucket was not the waterfall but the bridge that passed over it. The bridge was the one point at which workaday life brought citizens of Pawtucket into contact with the falls. The bridge had been thrown—not by Slater, but by proprietors early in the eighteenth century—directly across the line of the falls, and it too hid the waterfall. The water was high to the north of the bridge and lower and more

troubled to the south, but walkers could view the falls themselves only if they paused to lean over the south rail. In views of Pawtucket, they seldom did that. When an artist early in the nineteenth century sketched the falls and bridge he pictured a lone walker and men in a carriage passing over the bridge. Their gazes are fixed straight ahead as they pass high over the river and at a level with the village, moving resolutely through Slater’s landscape while the water roars and crashes far beneath them.

Pawtucket Falls, by J. R. Smith (author’s collection)

An occasional visitor lamented that the bridge ruined the view of the falls. One Englishman insisted that “the scenic effect of the fall is most materially injured by the situation of Pawtucket bridge,” and Josiah Quincy of Boston agreed that the bridge “hides much of the grandeur of the scene.” But such complaints missed the point: while the bridge hid the waterfall, it used the falls to call attention to itself and to the built landscapes that it joined together. Pawtucket owed its growth to the technological conquest of a waterfall. The layout of the village and the placement of the bridge completed that conquest visually and emotionally. 61

An occasional visitor explored the wilder territory below the

falls. The Frenchman Jacques Milbert looked downriver from the bridge in 1818, and left a picture of what he saw:

After crossing several dams the river advances with apparent calm until it suddenly leaps sixty feet in a magnificent cascade. From this same point of vantage I could see the water boiling after its drop between massive perpendicular rocks that are remarkable for their imposing elevation. Trees growing out of these natural walls arched over the precipice, making it very dark. [Milbert found a pathway and] stood at the foot of the falls, where I could see the whole picture. My ear was deafened by the roar of the cataract and my eyes bedazzled by whirling waters and spurting snowy foam. I saw waves force their way between rocks they had rounded or break on others whose sharp points revealed their primitive character. The pressure of the falls on the air was so strong that the foliage was kept in constant motion. A brilliant rainbow touching first one bank then the other was the final poetic note in this magnificent picture, in which the rustic mills bordering the falls and the bold bridge surmounting it were not unworthy accessories.62

In more boisterous and less educated ways, Sam Patch and the other factory boys knew the waterfall that had dazzled Milbert. In the mills, underneath the clatter of machinery and the shouts of the bosses, the invisible falls sent up their magic and incessant roar. And at night, when the mill canal was shut down and the river ran with full force, the waterfall rattled windows and invaded the imaginations of boys all over town.63

Whenever they were free, the boys and young men of Pawtucket converged on the falls. The tides from Narragansett Bay brought ocean fish all the way up to that point, and men fished from the bridge and from the shore below, or threw out nets from rocks in the stream itself. The boys swam, they took boats into the pool below the cataract, and they played and fished along the banks. These were times given over to the rough, democratic companionship of boys, to the seductive roar and disorder

of falling water, perhaps to the first experience of the warm, comforting blur of alcohol. Some of the boys, Sam Patch among them, took chances there.64

Early on, boys began jumping from the bridge into the river below the falls. It was a drop of more than fifty feet, and the bottom was rocky and dangerous. At one spot near the east bank, however, the falls had carved a deep hole, and there the aerated water was, as a local journalist put it, “nearly as soft as an ocean of feathers.” The boys called it “the pot.” In 1805, when the fourstory Yellow Mill went up on the east side just below the falls (two stories above road level, two below), the jumpers wasted little time. That year three young men made the astounding eighty-foot leap from the peaked roof of the Yellow Mill into the pot. In 1813 the six-story Stone Mill went up on the east side, just below the bridge. In ensuing years the bravest Pawtucket boys—Sam Patch among them—regularly made a running leap from its flat roof into the pot, a descent of close to one hundred feet.

Pawtucket Falls, by J. Milbert (Print Collection, The New York Public Library)

The jumpers attracted crowds, then the attention of the authorities .

“Although no one was hurt by this unusual sport,” reported Reverend Benedict, “yet there was a hazard, and not always a decency [some of the boys were naked?], in the performance, which, in the course of a few years, led the citizens to break it up, and young Patch wandered off in other regions in pursuit of this strange and anomalous vocation.” But in fact the ban on jumping was either ineffective or came long after Sam Patch had left Pawtucket; boys leaped from the Yellow Mill at least as late as November 1829.65

Falls jumping, like mule spinning, was a craft. It called for bravery that verged on foolhardiness, but it required selfpossession and a mastery of skills as well. The Pawtucket boys all jumped in the same way: feet first, breathing in as they fell; they stayed underwater long enough to frighten spectators, then shot triumphantly to the surface. It was truly dangerous play, but people in Pawtucket—both jumpers and spectators—knew that the leaper would be hurt only if he lost his concentration and did not follow the rules. Most of the leapers were factory boys, but sons of farmers and artisans, locals who despised the mill families, also turned up at the falls. Two of the three young men who first jumped from the Yellow Mill were blacksmiths, one of them a son of Nehemiah Bucklin, the farmer who had owned the property on the east side of the falls before the factories came. The waterfall may have been the one place in town where the prejudices, failures, and forebodings of adult Pawtucket could be forgotten—a place where boys could take the measure of each other as boys and nothing else. It was there that Sam Patch began turning himself into a hero.66

Mule spinning and falls jumping: they were two ways in which Sam Patch separated himself from the devastating legacy of Greenleaf Patch, and from Abigail Patch’s grim struggle to make decency out of hard work and family secrets. In the spinning

room and at the waterfall, Sam Patch fashioned skills, a reputation, and a sense of his own worth that had nothing to do with his family’s history. He modeled himself after the most admirable men and the bravest boys he knew, and he forged an identity out of his own trained and practiced performances. Given what he had to work with, Sam Patch was beginning to make something of himself.