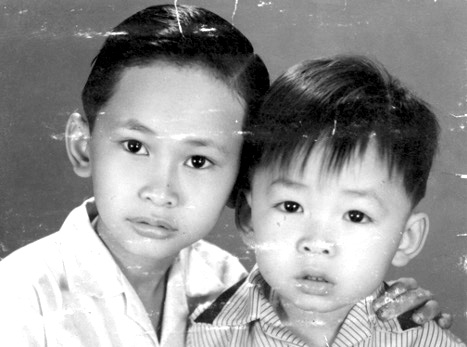

portrait of the writer as a young fathead

It’s enormous. Your hat size is extra large because extra extra large isn’t easy to find. The size of your head has nothing to do with the rest of you, which is of average height and weight. At two years of age, your head is a touch bigger than your nine-year-old brother’s. Your brother is beautiful, but you . . . look kind of bewildered. A foreshadowing of your years as a fuckup.

You do show a flash of early talent when, in the third grade, you write and draw your first book. Lester the Cat is a minimalist character study of Lester, an urban cat, stricken with ennui. Bored with city life, Lester flees to the countryside. There, in a hay-strewn barn, he falls in love with a country cat.

You have never even petted a cat in your young life, but you must have captured the authenticity of urban feline alienation, for the San José Public Library awards Lester the Cat a prize. Since Ba Má cannot leave the SàiGòn Mới to take you to the ceremony, your school librarian picks you up from home and treats you to a hamburger across the street from the library. The hotel restaurant, the first one you can recall sitting in that does not serve Vietnamese food, strikes you as incredibly luxurious. You don’t remember the white-haired librarian’s name, but you are eternally grateful to her and to the San José Public Library for setting you on the path to more than thirty years of misery in trying to become a writer.

Eventually you give Lester the Cat to J. The book fades from your memory, as does your childhood promise. Kingston gives you a B+. You were, she tells you decades later, the worst student in the class.

At twenty-one, you are a better literary scholar than writer. You stay at Berkeley to pursue your doctorate in English, but promise yourself that once you get tenure, you will do whatever you want, since you cannot be fired.

You will write.

As a literary critic, you want to criticize colonialism, capitalism, and racism and to study literature by people of color, especially Asian Americans. You tell your English department chair, one of the most famous American literary scholars in the country, that you want to write a dissertation on Vietnamese American literature. He gazes at you with mild concern through his glasses and says, You can’t do that. You won’t get a job.

Perhaps true, perhaps not. But you are outraged. The right response is not to accept the status quo but hope to transcend it. If not today, then in the future. Your department, however, believes in tradition and the canon, requiring you to read Beowulf through Chaucer and Shakespeare, the Romantics and the Victorians, the realists and modernists, so you can talk to your entire profession.

Too bad much of the profession cannot talk back to you.

As a professor of Chicano literature in your department tells you with an edge of anger, the door to his office closed, They expect us to read their literature, but they won’t read ours.

So-called minorities must always know the minds of the so-called majority. But they assume they need know nothing about you. Their ignorance is a privilege, a luxury you cannot afford.

A quarter century later, in response to students demanding greater diversity in the English curriculum at Barnard College—the same cause you campaigned for as a student at Berkeley—the college’s Emerita Helen Goodhart Altschul Professor of English says:

You need to have read some Shakespeare,136 Milton, Tennyson. This

is good background for an English major. The brutal part of my

mind says, “If you don’t like it, don’t major in English.”

Love it or leave it. The professor has said the

quiet part out loud, the part you suspect is

sometimes or often said in the privacy

of faculty clubs, cocktail parties,

conference receptions, and

tenure reviews when the

audience is all white.

She continues:

Many professors would feel that137 if you don’t give

the basics of the British literature supplemented

by American literature, you simply can’t

understand some of the moderns.

You grew up in San José, California, so mentally colonized

by the English culture you encounter in the library and

on television that you become an Anglophile. As an

adolescent, you read Vanity Fair and Tom Brown’s

School Days for fun. But the brutal part of your

mind says if one does not read the literatures

of people of color and the colonized,

one cannot understand that

slavery’s profits make European modernity possible,138 as does the European exploitation of the Americas and its Indigenous peoples.139 The bloodstains from these profits are laundered through the denial by Europeans of their inhuman behavior.

Understanding how English literature often

participates in this denial and projects

this inhumanity onto the enslaved

and the colonized is good

background for an

English major.

At Berkeley, you become what academics call an Americanist. You obtain your first passport so you can travel to international conferences. During your oral examination in nineteenth-century American literature, the examining professor spends half the time interrogating you about one scene in Moby-Dick. Fortunately, you have read Moby-Dick (loved it!) and remember the gold doubloon nailed to the mast of the Pequod by Captain Ahab.

You write a dissertation on Asian American literature, a field in which you can find an academic job because of the struggles of an entire Asian American movement that has succeeded in making Asian Americans and their writings more and more visible. This movement lives inside and outside of academia, from organizers and politicians to artists and activists. Your dissertation is partly about how literary and political struggle go hand in hand, how both are needed for changing and transforming self and society, voice and art. You write about Sui Sin Far (Mrs. Spring Fragrance, 1912), Carlos Bulosan (America Is in the Heart, 1946), John Okada (No-No Boy, 1957). Almost no one who does not teach or study Asian Americans has heard of them, even Bulosan, who was famous in his time.

America Is in the Heart dramatizes the migration of Filipino men to the Depression-era United States. Allos, the narrator, becomes Carlos in the United States and then, by the end, Carl. This work of fiction and autobiography foreshadows today’s autofiction, so fashionable when written by white people, not so fashionable when written so much earlier by a colonized person. Bulosan understood that the borders between genres do not matter when colonizers routinely violate existing borders and create the borders they want, while the colonized are forced to cross those borders just to survive.

America Is in the Heart was published during World War II, when AMERICATM knew it had to live up to its rhetoric of freedom and democracy. So, after hundreds of pages depicting American colonization in the Philippines and brutal racism against Filipinos on the American West Coast, a politically conscious Carl (as in Karl Marx) concludes by saying:

It came to me140 that no man—no one at all—could destroy my

faith in America again. It was something that had grown out

of my defeats and successes, something shaped by my

struggles for a place in this vast land. . . . [S]omething that

grew out of our desire to know America, and to become a

part of her great tradition, and to contribute something

toward her final fulfillment.

This ending puzzles you for years until you understand that it makes sense if Groucho Marx reads it aloud, waggling his eyebrows and rolling his eyes at every mention of AMERICATM, the most exclusive club of all. Bulosan should have been a Great American Novelist, but by 1957 he was dead on the steps of Seattle City Hall, ill with tuberculosis and alcoholism, tracked by the FBI at the peak of American anti-communist paranoia. Caught between AMERICATM as a welcoming heart and a colonizing hammer, Bulosan’s epic is really a Not So Great American Novel.

So is Tripmaster Monkey, Kingston’s satirical, loving depiction of hippie Asian American artists in San Francisco and Berkeley during the countercultural revolution of the 1960s. The hero is the idealistic playwright Wittman Ah Sing, and since the novel is also about AMERICATM as the land of democratic Whitmanian possibility and AMERICATM as imperialist warmonger, it should be a Great American Novel but is not mentioned as such by those who keep track of such things.

It’s mostly these literary people who have heard of Kingston in a mostly nonliterary world. Only when you mention Amy Tan and her immensely popular The Joy Luck Club do other people start nodding. Wayne Wang directs the movie adaptation starring the hunk who could also play your father, Russell Wong. He smashes his fist into the red meat of a watermelon and then eats a handful of it with juice dripping down his chin while he smirks suggestively at a youthful Ying-Ying, played by Feihong Yu (the older Ying-Ying is played by France Nuyen of Star Trek fame, who could also portray your mother in the epic movie of her life if Joan Chen or Kiều Chinh are unavailable).

When you encounter The Joy Luck Club at eighteen, it is the first book you have ever read by an Asian American (and by someone who attended college at San José State, a few blocks from your brown house). Your literary models have been Jane Austen, Lord Byron, and Percy Shelley, writers completely alien to Ba Má. English exists only for your own pleasure, irrelevant to the world of the SàiGòn Mới. The Joy Luck Club reorients you, along with works by many other Asian American writers: Jessica Hagedorn (Dogeaters), Theresa Cha (Dictee), David Henry Hwang (M. Butterfly), Frank Chin (The Chickencoop Chinaman). Asian Americans have written in English since the nineteenth century, beginning with Sui Sin Far’s sister, Onoto Watanna, the Japanese pen name of Winifred Eaton, born in Canada of a Chinese mother and English father. Through Asian American literature—and Native literature, and Chicano literature, and Black literature, and anti-colonial literature—you construct a literary inheritance for yourself in addition to the genealogy of the Anglo-American-European canon, which is also yours. And you wonder:

Perhaps writing can be an act of justice. Perhaps through writing

you can illuminate the shadows of the SàiGòn Mới, the brown

house on South Tenth Street, the realm of Vietnamese

refugees. Perhaps writing can be beauty and

light and also rage and anger.

And if you cannot write a dissertation on Vietnamese American literature, you will write Vietnamese American literature. In the early 1990s, only a handful of books have been published by Vietnamese or Vietnamese American writers in English. You are determined, against the dehumanizing force of Hollywood and its crimes of representation against Vietnamese people, to humanize the Vietnamese and give them a voice.

This is a mistake. You will not be able

to say why for years or to do

otherwise for decades.

So you attempt to be a writer, although you do not dare call yourself one. You write poems: a sonnet about your absent sister, another earnest one in free verse titled “Cambodian Boy on a Stairway,” about a black-and-white photograph featuring a survivor of a rocket attack. The poignancy of that lone boy moves you deeply.

Unfortunately, this does not make you a good poet.

You stop harming yourself and others with your verse. Essays and nonfiction are closer to the academic writing at which you excel. This is how you end up in Kingston’s nonfiction seminar.

You remember falling asleep in her seminar. But you do not remember writing about Má in the Asian Pacific Psychiatric Ward until you open your shabby archive decades later and are surprised to learn from the essays you had written in Kingston’s class that your mother was in the ward when you were nineteen.

Not when you were a child.

Your big head holds so many big ideas and remembers so many things about important books, down to the doubloon on a mast in a thick novel written in a language your mother barely reads.

But you cannot or will not remember

who you were

when your mother was not

who she was.