3

Burford Priory

Oxfordshire

SOME COTSWOLDS HOUSES have changed little over the centuries, while others have declined or been abandoned, only to be rescued and restored in modern times. Burford Priory was partly demolished in the early nineteenth century, and then uninhabited for decades before it was restored in the early 1900s, and later given over to institutional use. It has since been carefully transformed into a family home by Matthew Freud.

Burford Priory sits on the edge of the famous Oxfordshire town of Burford overlooking the Windrush valley, and began life not as a priory but as a small Augustinian hospital dedicated to St John. It was founded in 1226 by William, Earl of Gloucester, and after the Dissolution in 1543 the property was granted to Edmund Harmon, barber-surgeon to Henry VIII and Master of the Barbers’ Company (whose lavish tomb can be seen in the nearby parish church).

In 1580 the Burford property was bought by Sir Lawrence Tanfield, an ambitious lawyer and MP, who enlarged the surviving buildings to form an extensive E-plan house with gabled wings (much larger than the present house). The highly decorated three-storey porch with Ionic and Corinthian columns features carved figures, possibly Hercules and Antaeus. Tanfield entertained James I here in 1603 and acquired the lordship of the manor. The house was inherited by his grandson Lucius Cary (later 2nd Viscount Falkland, who died at the Battle of Newbury.)

The romantic, gabled mansion of Burford Priory, once a much larger sixteenth-century house, reduced in scale in 1808, restored in the early twentieth century – it became a monastery for many decades. To the left is the late seventeenth-century chapel.

A detail of the sculpted porch with carved muscular figures thought to be characters from classical mythology, possibly Hercules and Antaeus.

Looking through the arch in the entrance hall, one of the few visible links to the medieval Augustinian hospital.

‘It was an extraordinary privilege to restore such a house.’

MATTHEW FREUD

In 1637, Lucius Cary sold it to Sir William Lenthall, speaker of the House of Commons, who courteously defied Charles I when he came to arrest five MPs for high treason. Lenthall’s refusal to reveal the MPs’ identities in the chamber led the king to dissolve parliament; this is considered a cause of the Civil War which broke out later that same year.

As speaker of the Long Parliament, Lenthall was a pivotal figure of the Commonwealth, but survived the Restoration, although humbled and barred from public office. He added an elegant neo-Gothic chapel, which is usually dated to its consecration in 1662, the year of Lenthall’s death (perhaps as an atonement for his part in the Civil War and Commonwealth). He also introduced the magnificent decorated classical chimneypiece in the great parlour. Lenthall had an important art collection, including Holbein’s famous portrait of Thomas More and his family, as well as works by Corregio and Van Dyck.

The house remained with the Lenthall family but their fortunes declined, and the house was radically reduced in size in 1808, and sold in 1828. It remained uninhabited and eventually became ruinous until it was bought as a restoration project by Colonel F.B. de Sales la Terrière, in the era of many manor house restorations. He employed the mason Alfred Groves. Their work included the re-erection of the thirteenth-century arches that they uncovered within the building. The restoration was recorded by Country Life magazine in 1911. In 1912, it was sold to the philanthropist E.J. Horniman, MP – wealthy from a famous tea-importing company and son of the founder of the Horniman Museum. He continued the restoration with the architect W.H. Godfrey until his death in 1932.

Sir Archibald and Lady Southby acquired the house after Horniman’s death and completed the restoration of the long roofless chapel, which was reconsecrated in 1937. In 1939, the architect Godfrey wrote a full account of its history and restoration, and noted ‘it has experienced profound changes, it has survived at least two periods of neglect, and now it has become a favourite and familiar example of an English home of especial beauty and charm . . . an acknowledged masterpiece.’ Used by airborne division troops during the second world war, from 1949 to 2007 the priory was an Anglican convent, firstly housing nuns of the Society of the Salutation of Our Lady, and from 1987 shared with Anglican Benedictine monks (they all moved to a new monastery in 2008).

Hospitality and home, lovingly restored: the principal dining room.

Looking down into the 1660s Chapel.

The main staircase, of the early eighteenth century with barley sugar balusters.

The great parlour with the huge carved chimneypiece introduced for Speaker Lenthall.

A restored oval window.

A detail of the chimneypiece in the great parlour, showing its classical decoration.

Matthew Freud outside the restored seventeenth-century chapel with his fox labrador, Vincent.

New lease of life

In 2007, Burford Priory was acquired by Matthew Freud and Elisabeth Murdoch. They spent six months restoring the rectory (designed and built by William Groves, a mason who worked for Christopher Wren), which they moved into in Easter 2008. They then carried out a major restoration project on the priory, completed in 2010. Matthew Freud recalls: ‘I had been looking for a house for twenty years; a house with history was important to me, and we wanted to be in a town, as we had previously lived on the edge of Woodstock. We wanted to have a house of architectural character – my grandfather was an architect who came out of Bauhaus, and my first home, Brewhurst, was Elizabethan. One day I was looking at Country Life, and had an odd thought, that the next page I looked at might hold the house I would live in for the rest of my years, and turned the page to see Burford Priory.’

The restoration was a massive project, which Mr Freud managed with building contractor Paul Carter and architect Alan Calder: ‘This kind of restoration, respecting the best of the past and making it liveable, gives you a feeling of having earned the right to live in such a house.’

The house was in a poor condition, so masonry and roofs were made sound, and many rooms returned to their original dimensions. The seventeenth-century chapel was in a state of disrepair.

Mr Freud recalls: ‘We were dealing with something on a grand scale, seventy-three rooms; and we were determined to make it work for a family with six children. Country houses were designed to be forbidding, and I wanted ours also to be welcoming and inclusive. When we finished the house, I went out and hung two swings on a tree!’

Art with purpose

Mr Freud, who has an extensive collection of modern art in his London homes, has collected mostly historic art for Burford Priory: ‘I spent three years buying, with an idea that most pictures should have a loose connection with the history of the house, including portraits of Charles I and Oliver Cromwell, both of whom visited the house. It took me eight days to hang the pictures; in the study I have a framed letter signed by every king or queen who visited this house. There are a few works by Lucian Freud and Damien Hirst which extend the story.’ As for furniture, Paul Brown and his team at Gateway workshop in Burford did most of the joinery, and he also made a new cabinet for the hall with the inlaid initials of the family’s children.

‘It was an extraordinary privilege to be allowed to both restore such a house, and to put my own touch on a building that has a history which goes back in one form or another for 1,000 years,’ says Mr Freud. ‘Such work is in truth more art than science, but I hope I have ensured that this house can have a long future.’

Light and texture: looking across the principal landing.

The oak-panelled master bedroom, with tapestry and carved wooden bed.

A glimpse through a leather-faced door.

The family kitchen.

Works by Lucian Freud, Matthew’s uncle.

A gathering of the Freud family bike helmets.

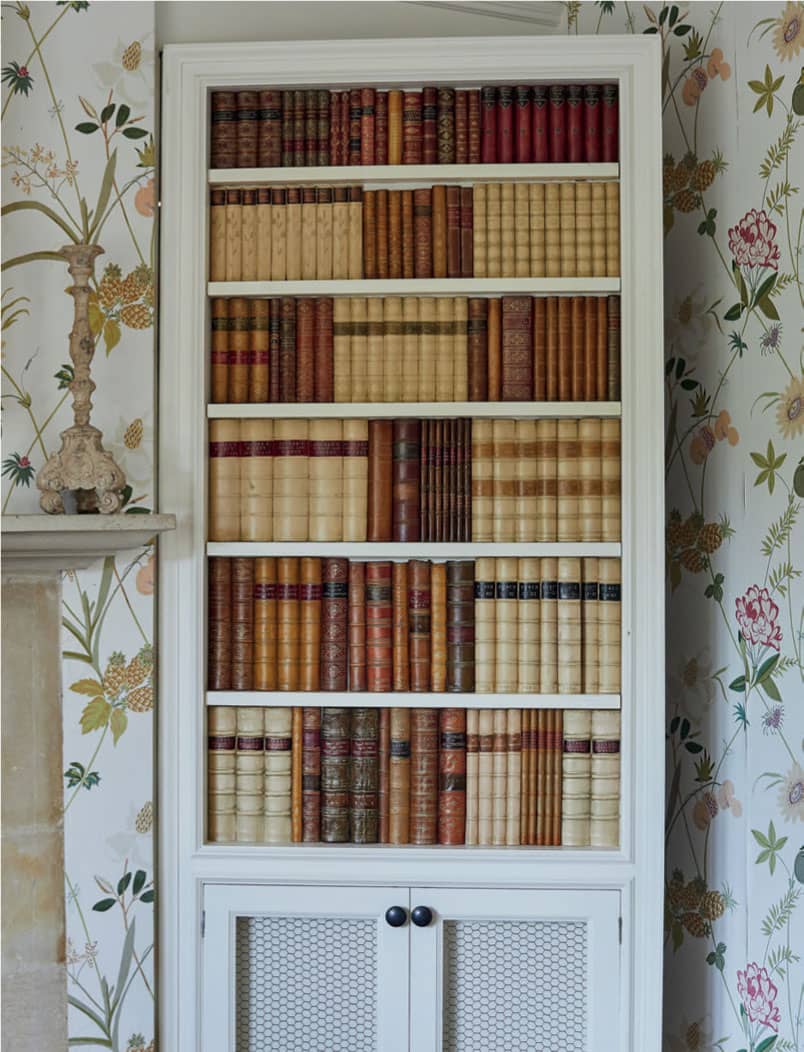

A jib-door disguised as a bookcase.

Surprises: a frogman’s suit, like a sculpture.

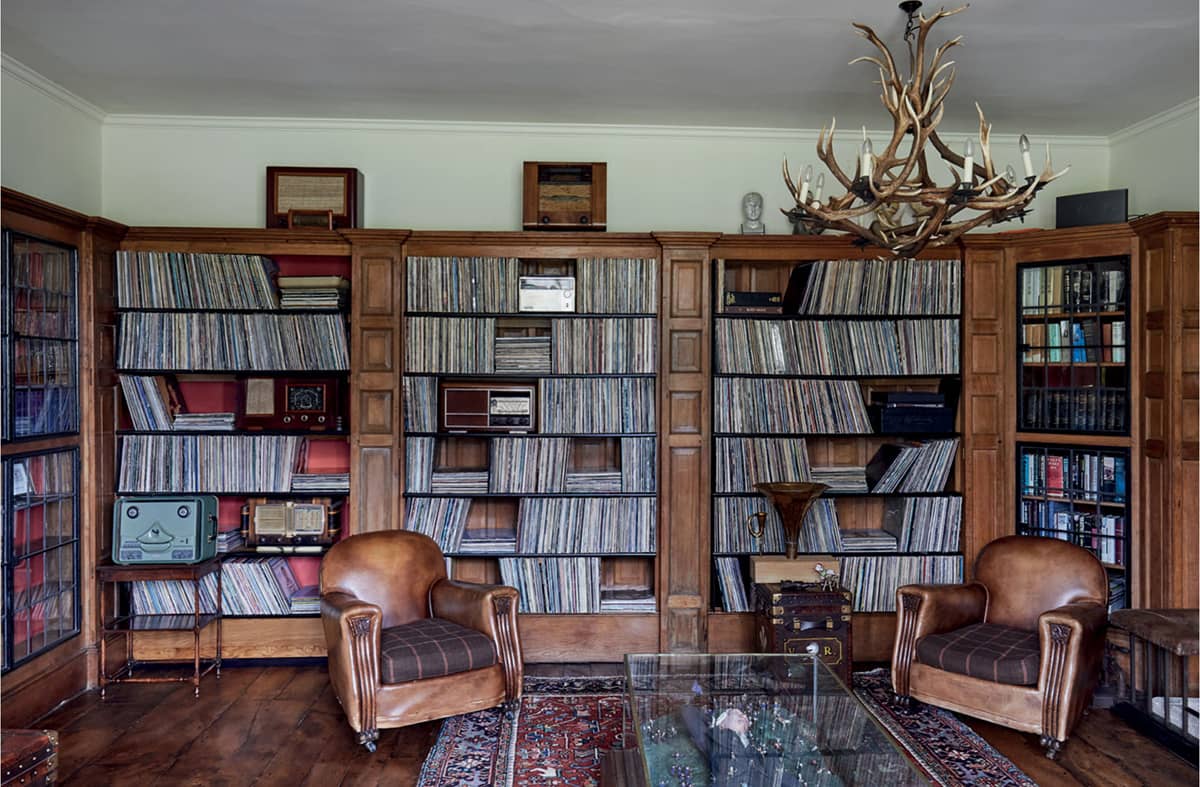

The library, lined with a collection of LPs.