7

Daneway

Gloucestershire

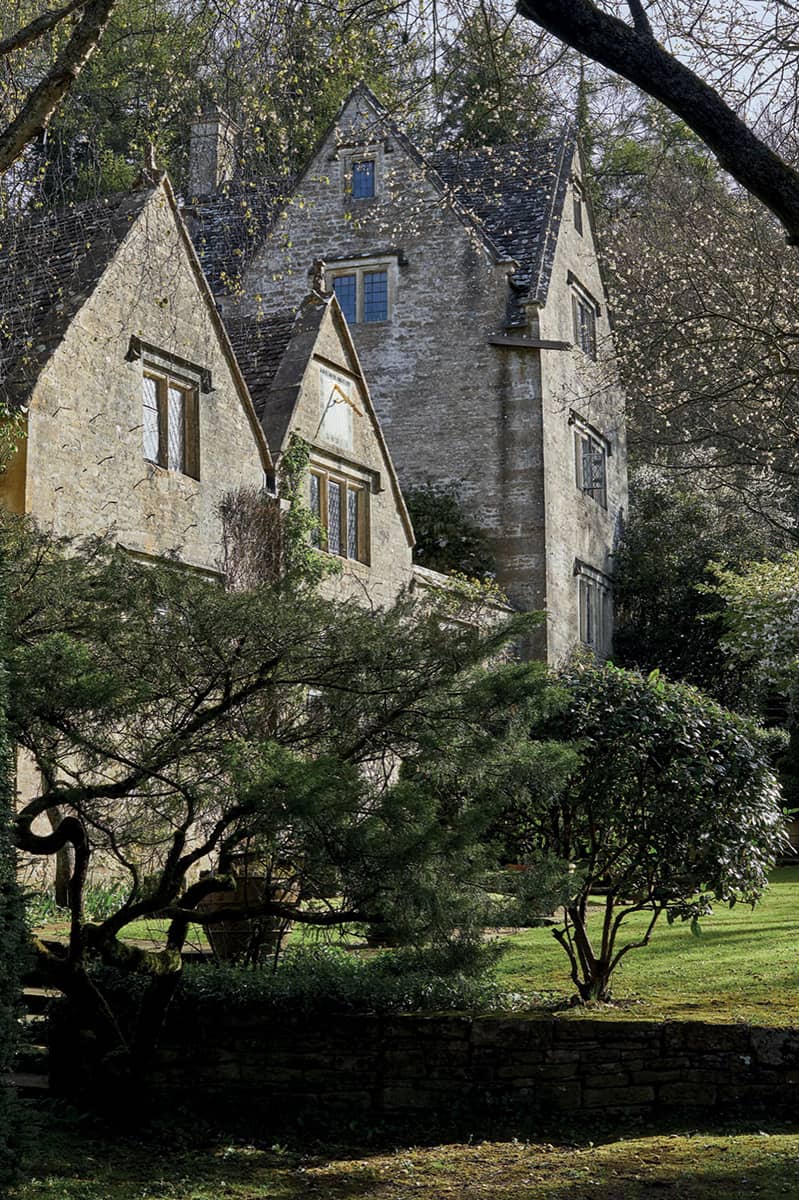

TUCKED AWAY in a wooded valley, Daneway has a feeling of other-worldliness, despite being close to the village of Sapperton. One of the older surviving manor houses of the Cotswolds, it dates mostly to the fourteenth century, adapted and extended in the seventeenth century. Warm and inviting, this neat, gabled, layered house folded around small courtyards was a subject of intense interest to arts and crafts idealists in the early twentieth century.

An arts and crafts cradle

Sapperton was for a time a happy centre of the arts and crafts, with a smithy and furniture-making workshop at the Daneway sawmill. Acquired and restored in 1899 for Earl Bathurst, from 1902 Daneway was leased as a showroom for Ernest Gimson and the Barnsley brothers, with their workshops in the stable. Thus it was not only home to a significant arts and crafts group but also, as the visitor book shows, much visited by prospective clients. The architect Baillie Scott made a measured survey in 1903, and there was also considerable interest in the cottage which Gimson designed and built nearby.

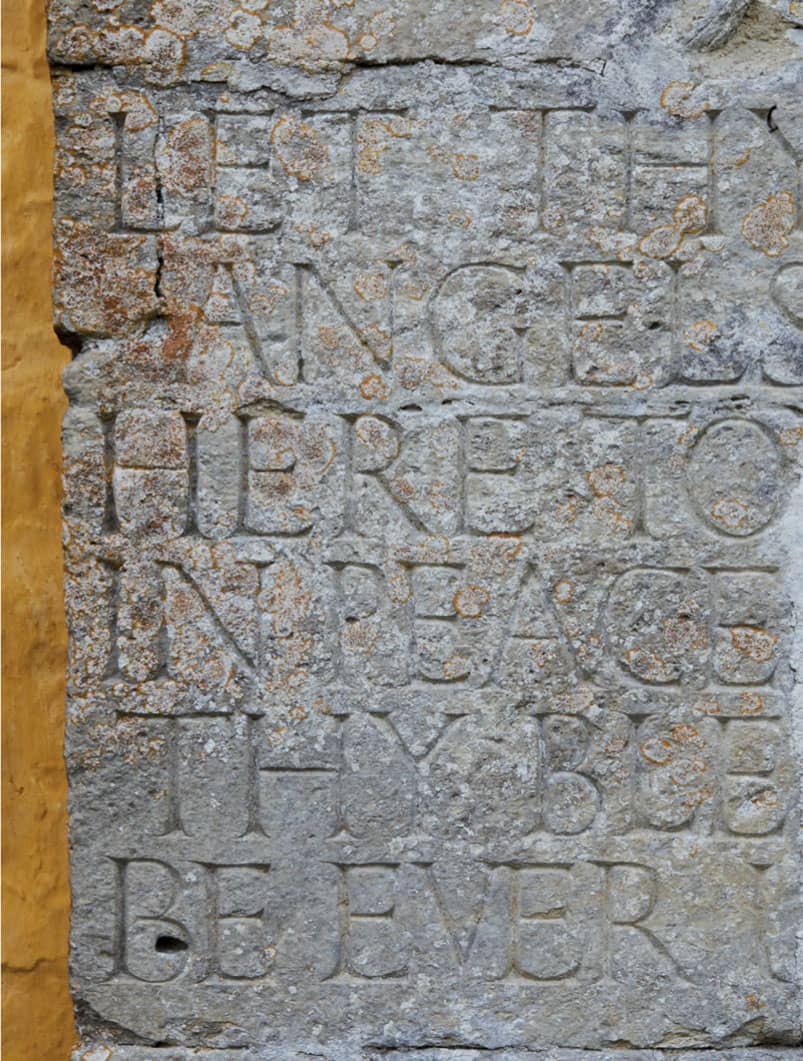

Oliver Hill, an architect who unusually links the arts and crafts and the modern movement, came as a tenant of the house in 1949 and kept the flame of arts alive here until 1968. Simon Verity (nephew of Hill’s wife Titania) carved celtic lions on a stone chimneypiece for a bedroom, as well as an inscription in the garden recording how Oliver Hill, ‘Lover of Life’, had made the garden there. Hill himself made a number of modest alterations, including the insertion of a window to the courtyard now overlooked by the great hall (drawing room). He used a late seventeenth-century style oak frame and enlivened the glass with painted lettering by Hans Tisdall, recording key moments and personalities in the history of the house. Hill also designed new garden terraces, and took planting advice from Vita Sackville-West. From 1974, Daneway was leased by his set-designer brother-in-law Anthony Denny, brother of the expressionist painter Robyn, and father of the stained glass artist Tom Denny, who has designed windows for Tewkesbury Abbey and Malvern Priory.

The comfort of ages: the great hall, created from the fourteenth-century hall which had been given a ceiling and wide hearth in the mid-sixteenth century – the window into the small court was designed by architect Oliver Hill.

The stone-flagged passageway leading through the house from the entrance.

A house renewed

In 1993–6 the house was repaired, restored and adapted by Johnston Cave Associates for Nicholas and Kai Spencer, who bought the freehold from the Bathurst estate. ‘This has been an ongoing love affair,’ says Mr Spencer; ‘we knew it was the right house as soon as we saw it – we hadn’t even seen inside.’ Mrs Spencer explains: ‘we moved to London from Bangkok and found ourselves often entertained in the country homes of friends, and began to think we would enjoy a house in the country; this rambling medieval house, romantic and low-ceilinged, has a very comfortable feel. We live in the whole house, no room is unused.’

‘This rambling medieval house, romantic and low-ceilinged, has a very comfortable feel.’

KAI SPENCER

With its solid stone house and courts and low outbuildings, Daneway has something of the look of a small imaginary town. The fourteenth-century great hall at the core of the house can still be clearly made out, although ‘ceiled’ in the mid-sixteenth century – its smoke-blackened braced collar-beam roof timbers can be clearly seen in the room above. Off the porch is a distinctive stone doorcase, with a decorative ogee head, thought now to have been the original door to an oratory chapel.

A tower-like 1670s addition – long known as the High Building – was made by the then bachelor squire, William Hancox. His father was a Parliamentary captain who had acquired the freehold of Daneway in 1642, which his family had leased since the 1530s. The 1670s work, in an old-fashioned style for its date, provided new rooms on four storeys: a wine cellar, a parlour, a bedchamber and winter dining parlour with a belvedere at the top, all connected by a stone spiral staircase. The old great hall seems to have become the servants’ hall, and the bachelor squire lived in the High Building.

The gabled porch entrance was added in the 1670s in a deliberately old-fashioned style.

The hidden house: the later seventeenth-century High Building added four storeys to the older manor house.

A detail of the prayer of blessing carved into the house for Oliver Hill.

The round-headed door from the small court to the High Building.

The ochre lime-washed west side of the house, and part of the garden designed by Mary Keen.

The stables.

Tucked into the hillside, Daneway’s gables seem to emerge from the greenery.

Nick and Kai Spencer, for whom the house was carefully and tactfully restored in 1993–96.

The Spencers’ program of sensitive restoration and refurbishment preserved all the famous beauty of the house while ensuring long life for the structure. Mr Spencer says ‘the friend who suggested we look at Daneway said it was a house of extraordinary quietness, which is true; she also said it “needed a bit of work” which was certainly true.’ Dr Warwick Rodwell, later the archaeologist for Westminster Abbey, was closely involved in examining Daneway’s history throughout the three-year project. Through dendrochronology he dated the hall at the centre of the house to 1315, and he also identified the subdivided solar.

Preserved and enhanced

Their architect, Oxford-based ‘Nicky’ Johnston, helped them preserve everything of significance and open up areas which had been subdivided in the nineteenth century – one of the most extraordinary moments in the house is when you reach the head of the main stairs, and turn to look right through the rib-cage of stout roof timbers.

White-painted and light: the small dining room off the kitchen, in the early fourteenth-century house.

The rib-cage-like roof timbers were originally open, and the floor inserted in the mid-sixteenth century.

A detail of the carving mounted on the beam over the hearth in the drawing room.

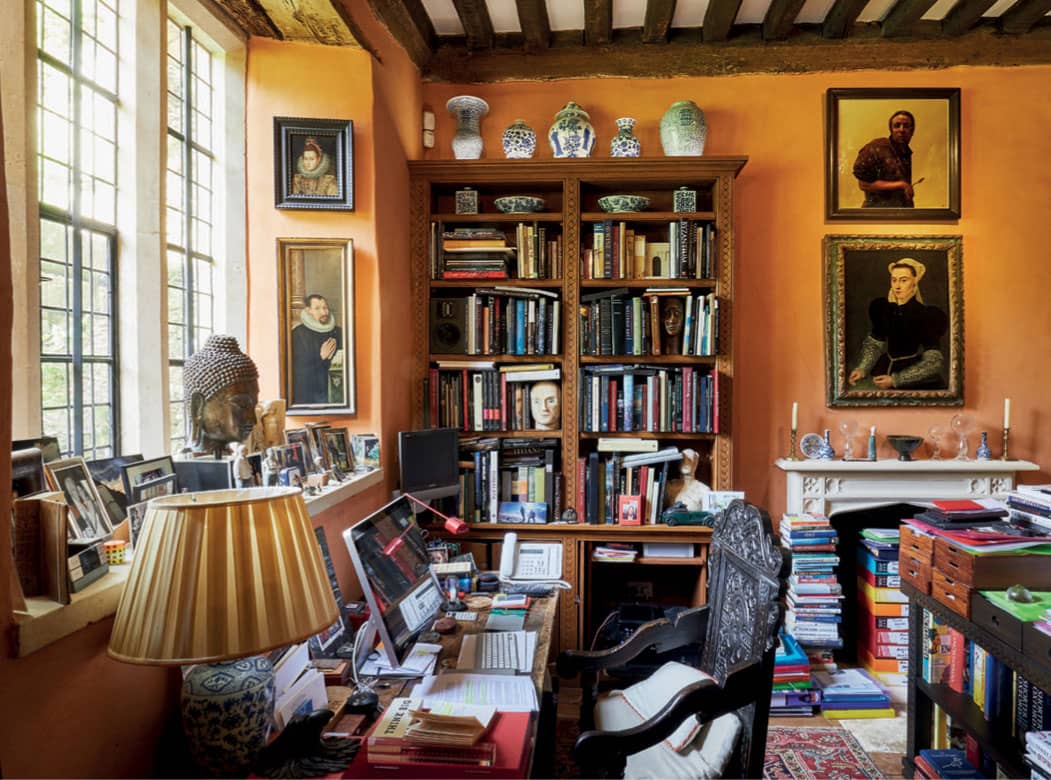

The book-filled study created out of a room previously used as a kitchen.

The new kitchen created by Nicky Johnston for Kai Spencer.

The oak treads of the newel stair in the 1670s High Building.

The larger dining room with its suite of seventeenth-century furniture.

The Trout Room, with its original stone-carved chimneypiece and simple plasterwork.

Off the great hall, a modern kitchen was removed and became a new book-filled study. New larders and sculleries were added to the main kitchen by excavating underground. Mr Johnston had to overcome considerable problems in sensitively replumbing, heating and wiring a Grade I medieval house.

The Spencers celebrated the many skills which make the repair and renewal of an ancient house possible by commissioning a stone (designed by Rory Young) carved with all the names of the builders and craftspeople involved in the work. They also commissioned Madeleine Dinckel to add more recent names and dates to the lettered window.

They also appointed Mary Keen to revive and extend the gardens first laid out by Oliver Hill, with vistas towards the fields and sculpture by Emily Young. The colour schemes for the interiors were carefully chosen, and the furniture selected to respect the age and feel of the house. Mr Spencer’s love of their new home led him to start collecting sixteenth- and seventeenth-century paintings, which they mix with modern art, and Mrs Spencer has brought textiles and sculptures from her own Thai heritage and from their travels around the world together; ‘every picture, every piece of furniture has been chosen together,’ she says.