14

Owlpen Manor

Gloucestershire

ENCLOSED BY STEEPLY RISING HILLS and surrounded by beech woods and sheep pastures, Owlpen Manor is one of the treasures of the Cotswolds. The small manor house forms an archetypal group, with the church of the Holy Cross, its own mill, banqueting house and barns all pressed into the steep hill. Writers recognise the special character of the house with great admiration and affection; the poet A.C. Swinburne wrote in 1894 to William Morris saying that Morris might make ‘a paradise incomparable on earth of the ruinous little old manor-house’ of Owlpen. Modern authors continue to be beguiled. In 1985 James Lees-Milne referred to it as ‘traditional, dignified and illogically satisfactory’. Hugh Massingberd called it ‘a breathtaking ensemble of truly English beauty’ in 1993.

The Oak Parlour, which was part of the early seventeenth-century remodelling, crammed with family photographs and portraits.

A house full of framed views into the past: looking through from the great hall into the Oak Parlour.

The sixteenth-century great hall, with its large round table covered with a crewel-work cloth, and laid for dining; the oak settle belonged to Norman Jewson.

‘A breathtaking ensemble of truly English beauty . . .’

HUGH MASSINGBERD

This old house, not far from Dursley, was acquired in 1974 by Sir Nicholas and Lady (Karin) Mander, who had married in 1972. They also managed to buy back much of the original demesne land of Owlpen, which they run as a diversified farm with forestry and holiday cottages, and they have repaired, preserved and also subtly extended the house. Sir Nicholas, who had grown up not far away in the North Cotswolds, says: ‘we arrived with two goats, two dogs and a baby; and didn’t quite know what to expect; we have grown with the house and the house has adapted to us.’ Lady Mander, who is originally from Stockholm, says: ‘the whole family has grown up here; five children, all now married, and Owlpen plays a role for the grandchildren too.’ There are now eleven grandchildren, making the immediate Mander tribe a grand total of twenty-three.

A historic core

The sculpted shapes in Owlpen’s rooms and passages are the result of centuries of habitation, happily filled with the paraphernalia of family life, alongside portraits and good oak furniture introduced by the Manders. The house has ancient roots and can be dated to around 1270, when it was built for the de Olepenne family, while the hall and chamber at the core of the house today, built by their descendants the Daunts, date to about 1523. Looking up at the house from its stepped and terraced garden (created in the early seventeenth century), you can immediately see the interventions of different ages: the three-storey bay window of 1616 to the west, and some early eighteenth-century sash windows on the eastern side (matched by early Georgian panelling inside). In the nineteenth century the house was inherited by the Stoughton family, who built a huge Victorian mansion on another part of the estate (later demolished), and Owlpen was left mostly empty.

With the growing interest in old buildings during the nineteenth century, and increasing interest in the authenticity of historic fabric, Owlpen Manor began to get a reputation as a rare survivor of another age. In 1906 Avray Tipping described it as in effect a ‘garden house’, and observed that it was ‘making its brave fight against consuming Time’. The owners kept a custodian servant in a wing, and visited it themselves for picnics and lent it out for church events – but it was otherwise unoccupied. In the following years, arts and crafts architects such as Sidney Barnsley and Alfred Powell, and active preservationists, such as Thackeray Turner and A.R. Powys of the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings, were lobbying to protect and preserve this delicate survival.

The limewashed east front of the house.

A breathtaking composition, manor house, banqueting house and parish church set into the steep hillside.

Looking away from the house across the yew-filled terraced garden.

The house seen from above.

The Grist Mill at Owlpen Manor, now a cottage.

The central part of the manor house seen through the early eighteenth-century gate piers.

Sir Nicholas and Lady Mander with children and grandchildren gathered on the early eighteenth-century steps.

Their anxiety was not just that the house might fall down, but that it would be unsympathetically converted. As Sidney Barnsley wrote in 1921, ‘It would be fatal if the house was ever again used as a dwelling place, as the alterations and repairs that would be necessary would mean its ruin.’ Fortunately it came to the attention of Norman Jewson, an arts and crafts architect who described his migration to the Cotswolds – ‘a part of the country little known at this time’ – in his memoirs, By Chance I Did Rove.

Looking through from the great hall into the Little Parlour, painted in shades of grey.

The delicate early eighteenth-century wainscot in the parlour; the alcove filled with china.

Jewson had seen the uninhabited house while on a bicycle trip from nearby Sapperton. He bought it in 1925 and restored the house, knowing he would have to sell it as soon as it was restored, but persuading himself that it was worth the risk to know he would pass it on with its worn and weathered beauty intact. His generous obituary in The Times singled out his restoration of Owlpen: ‘His architectural work has a dignity and simplicity in keeping with the traditional Cotswold manner. His buildings look as if they had grown naturally from the ground.’ These were just the qualities he admired in Owlpen itself.

House and especially garden grew in reputation in the early twentieth century. Gertrude Jekyll drew a recording plan of the garden and published it in Gardens for Small Country Houses in 1914. In 1941 Vita Sackville-West called it ‘a dream . . . [with its] dark secret rooms of yew hiding in the slope of the valley’. Geoffrey Jellicoe wrote of the garden that it was ‘as though the design has grown from the hillside . . . [and] this early garden is better related, in its romantic setting, than that of any other period to the countryside in which it stands.’

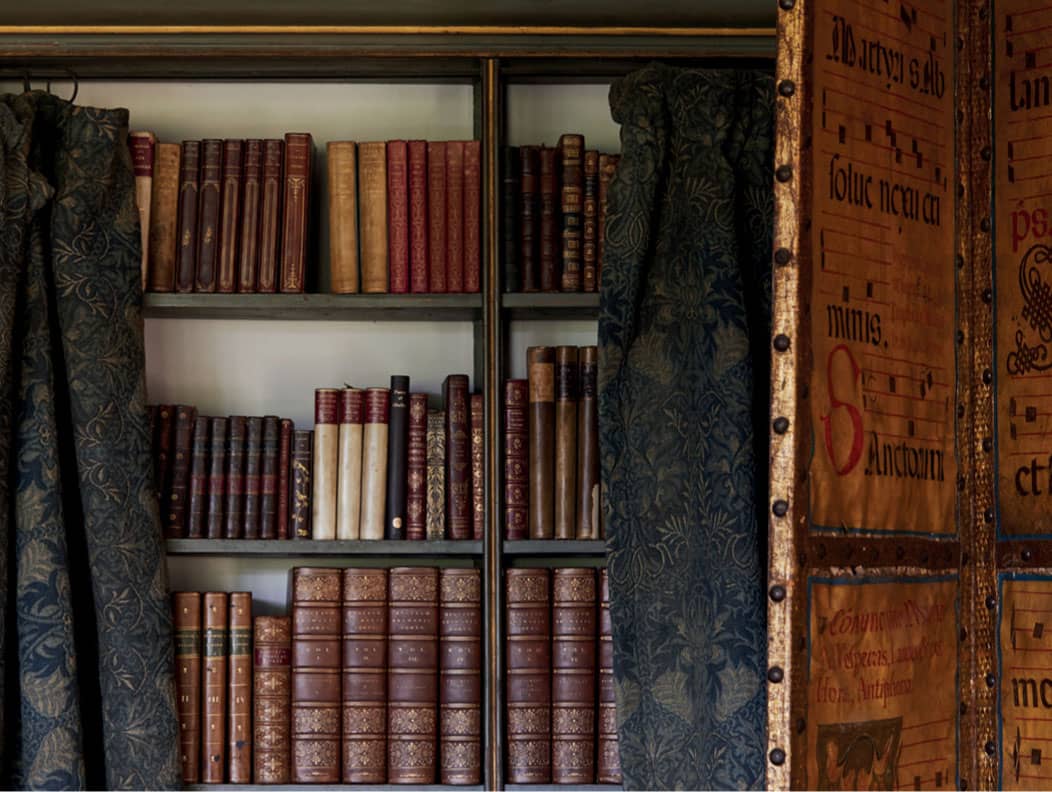

Adapting to modern life

When the Manders arrived they decided to ‘just spend a year in the house without doing anything, to see which rooms were light, which were warm . . . we called in David Mlinaric who said, “if that’s Owlpen, I have always wanted to help.” Pictures and furniture came from my family, who had a strong connection with the arts and crafts – we also acquired some pieces from David Verey’s collection, which had been at Arlington Mill. We had befriended the aged Norman Jewson, who to our surprise left us the papers relating to his repair work and some pieces of arts and crafts furniture, such as the Gimsons’ own settle in the great hall.’ Other important pieces at Owlpen include an oak table by Gimson and a desk and a bookcase by Sidney Barnsley.

‘We didn’t really change anything in the house. We did remove modern kitchen fittings and made the kitchen the centre of family life – it was described as a servants’ hall in Jewson’s plan. Rosemary Verey lent us sixteenth- and seventeenth-century garden books and treatises as we planned the sympathetic revival of the garden.’

The main rooms face south across the valley: the parlour, the great hall with its low ceiling, of which the main beams have been dated to the 1520s. The great chamber – known as ‘Queen Margaret’s Room’ in honour of a visit from Henry VI’s wife during the Wars of the Roses – is hung with an early eighteenth-century painted canvas depicting Joseph and his brothers, which has been in this house since 1719.

The long library to the east of the house was added only in 2012, designed by architect Toby Falconer. The single-storey, top-lit room has a turf roof on which the Manders keep chickens. Sir Nicholas observes: ‘Owlpen is rather smaller than the house I grew up in, but it has suited us so well, and we feel a great responsibility for the house, which looks like it belongs in a Samuel Palmer painting’.

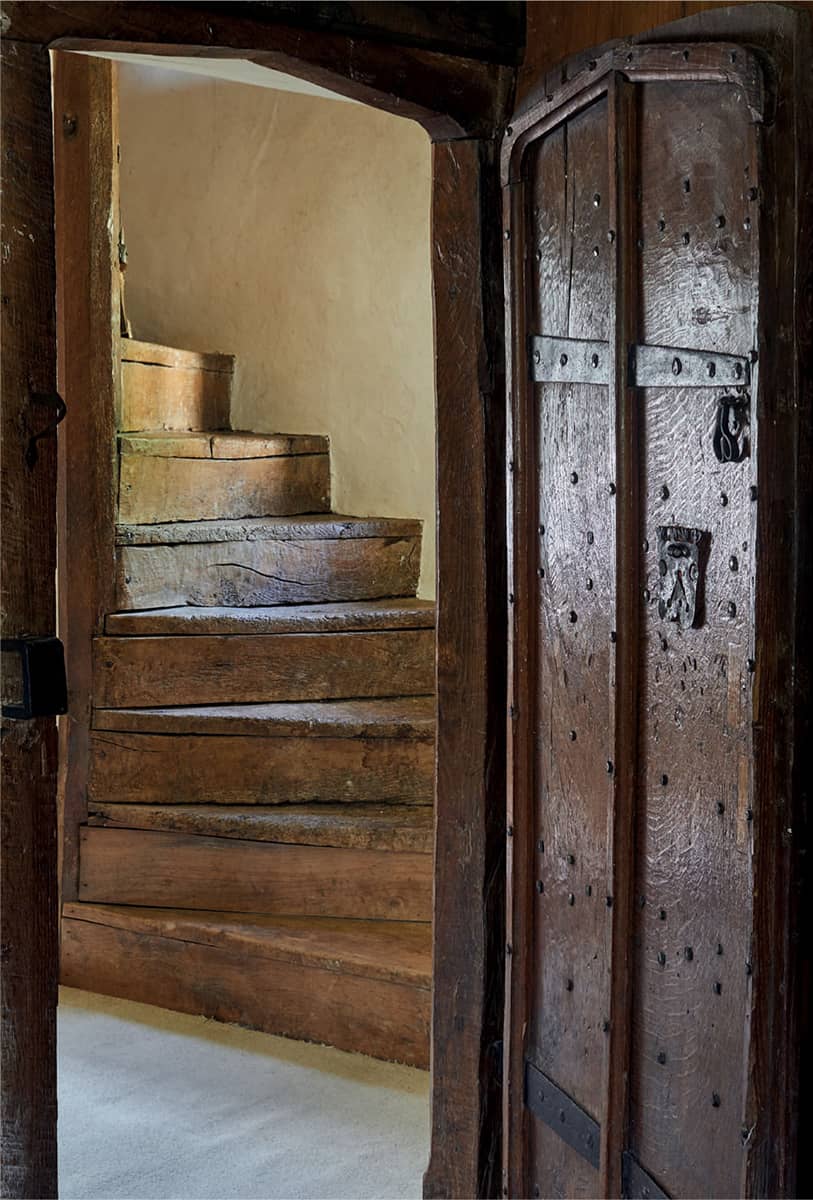

Looking through a sixteenth-century oak door from the original great chamber towards the oak newel staircase.

A four-poster bed in the bedroom over the Oak Parlour.

Books seem to flow through the house.

A detail of the early eighteenth-century painted canvas in Queen Margaret’s Room.

The oak settle designed by Ernest Gimson.

The new library designed by architect Toby Falconer.

The four-poster bed in the original great chamber, now known as Queen Margaret’s Room.

A plasterwork owl designed by Norman Jewson during his 1920s restoration of the house.

A detail of a ladder-back chair.