17

Sudeley Castle

Gloucestershire

LONG REPUTED as one of the inspirations for P.G. Wodehouse’s Blandings Castle, home of the fictional Earl of Emsworth, Sudeley Castle is an extraordinary sight. It is a grand stone edifice sitting under the Cotswold escarpment, built as a palace. A huge part of it today is a rambling ruin, surrounded by idyllic gardens; the remaining inhabited range makes an extensive and comfortable country house.

Today, Sudeley is the home of Elizabeth, Lady Ashcombe, who has been chatelaine here for forty-five years, and has been an exemplary champion of the house and its history. She inherited it on the death of her first husband Mark Dent-Brocklehust in 1972; it had been his family home. She shares the house with her children, Henry and Mollie Dent-Brocklehurst, and their families. Mollie, an art dealer, has recently brought major contemporary sculpture shows to the gardens here.

Sudeley Castle has a rich but complex (and royal) history, and is most famous as a home of Queen Katherine (Parr), the widow of Henry VIII. The current house is only a fraction of the original palace, and was created out of the fifteenth-century outer range – restored as a country house in the nineteenth century. The inner courtyard – now the grandest imaginable ruin, reminiscent of a stage set from an opera – included the principal rooms of the courtier house, held by the de Sudeley and then Boteler family until 1469, when the Castle was seized by the Crown and granted to the King’s brother, Duke of Gloucester (later Richard III), before it reverted to the Crown.

In 1547 Sudeley became the property of the ambitious Thomas Seymour, Lord High Admiral, who in that same year was married to Katherine Parr, widow of Henry VIII. He extensively remodelled Sudeley to make ready for a new dynasty, but Katherine Parr died in 1548, shortly after the birth of their one child Mary.

Thomas Seymour, who had flirted rather recklessly with the princess Elizabeth, was tried and executed shortly afterwards for plotting to usurp the throne. Katherine Parr’s brother, the Marquess of Northampton, inherited Sudeley, but after supporting the cause of Lady Jane Grey, promoted by Edward VI as his Protestant heir, he forfeited the house and lands. Mary Tudor then granted the property to Sir John Bridges, created 1st Baron Chandos of Sudeley.

The principal Stone Drawing Room, decorated in the 1970s with the advice of set designer Adam Pollock.

A picturesque roofline, the castle seen from the north west.

St Mary’s Church, surrounded by the castle’s gardens.

The ruins of some of the finest apartments of Sudeley Castle.

Sudeley then remained a Chandos property until 1649 when, after the 6th Lord Chandos had fought for the Royalist cause and the castle was twice besieged, it was ‘slighted’ by Order of the Council of State: the roof was removed and the building left open to the elements. A coaching inn was still being run in the remaining habitable part in the eighteenth century (when George III made several visits to the famous ruins).

For a brief time, Sudeley was owned by the extravagant Marquess of Buckingham and Chandos, who had intended a restoration in honour of his ancestors (he was made the 1st duke of the fourth creation in 1822). With some irritation, given his belief in his own social importance, the duke (who was later all but bankrupted by his extravagance) sold Sudeley in 1837 to two wealthy glove makers, John and William Dent from Worcestershire. They bought up a substantial landed estate around Sudeley, and (with a third brother Benjamin, a clergyman) were devoted to the place. They restored the surviving outer court as a comfortable residence with the young and energetic Gothic revival architect Harvey Eginton, with elaborate plasterwork ceilings and panelling (which survives best in the billiard room, originally the dining room). Eginton’s work was celebrated in 1848 in the Journal of the British Archaeological Association, which reported that ‘the ancient character of the mansion is preserved throughout.’

Revival and rescue

By 1855, Sudeley was inherited by John Coucher Dent who had, in 1847, married Emma Brocklehurst. Dent carried out further restoration of the church of St Mary’s and the castle with George Gilbert Scott. Much of the work was in fact by Scott’s former assistant, John Drayton Wyatt. In the 1850s they employed a decorator, Charles Moxon, who grained some of the panelling for John’s widow, Emma Brocklehurst. In the 1880s and 90s she also rebuilt the west range as offices and stables, and rebuilt the north-east gate. Further work by Walter H. Godfrey was carried out in 1930–6 for her son, J.H. Dent-Brocklehurst, who raised floor levels and created the handsome panelled library and morning room.

The Dents renovated the south-facing rooms of the east wing as their principal rooms of reception, and the south hall became the main entrance and staircase. There are also a series of fine bedrooms on the first floor, including the Chandos Bedroom, in which stands the bed thought to have been used by Charles I whilst on campaign, opposite which hangs a portrait of the king himself. The rooms associated with Katherine Parr had also been fitted out in the 1840s, with a Tudor-esque ceiling by Egington, and antique glass installed by Thomas Willement. Much of the antique glass and some of the fine historic textiles in the house were acquired by the Dents from the sale of Horace Walpole’s house, Strawberry Hill in Twickenham.

A modern chatelaine

American-born Lady Ashcombe came to live here in 1969, having married Mark Dent-Brocklehurst in 1962. She recalls: ‘I had no expectation then of moving to Sudeley, because although Mark’s father had died young, his mother was young and beautiful and had already steered Sudeley through the difficult war years. Mark and I both worked in London, so it came as a surprise when she suggested we should take over. To me it all seemed rather feudal then; there was an amazing collection of old master paintings and works of art, old-fashioned large-scale furniture, and very little in the way of heating or modern plumbing. Little had changed since the 1930s.’

Tragically, Mark Dent-Brocklehurst died in 1972. It was at a time of high taxation, but his young widow decided to try and hold on to the castle and estate for their two children, although the sale of many assets, land and works of art was necessary to pay off the death duties. She says: ‘Mark and I had only just begun to make ourselves comfortable at Sudeley, and the principal rooms in which I live now were the servants’ quarters when I first arrived.’

In 1979, she married Lord Ashcombe who had his own family estate Denbies in Surrey: ‘It was going to be difficult to run two country houses, and after a period my husband very generously decided to support me and my children here at Sudeley.’ Denbies was sold, and much of the furniture now in the castle comes from there; ‘Harry really made it possible for us to remain here.’ Lord Ashcombe died in 2013.

The billiard room.

A detail of a plasterwork ceiling.

The ornate nineteenth-century Tudor-style decoration of the Katherine Parr Room, celebrating the historic associations of the house.

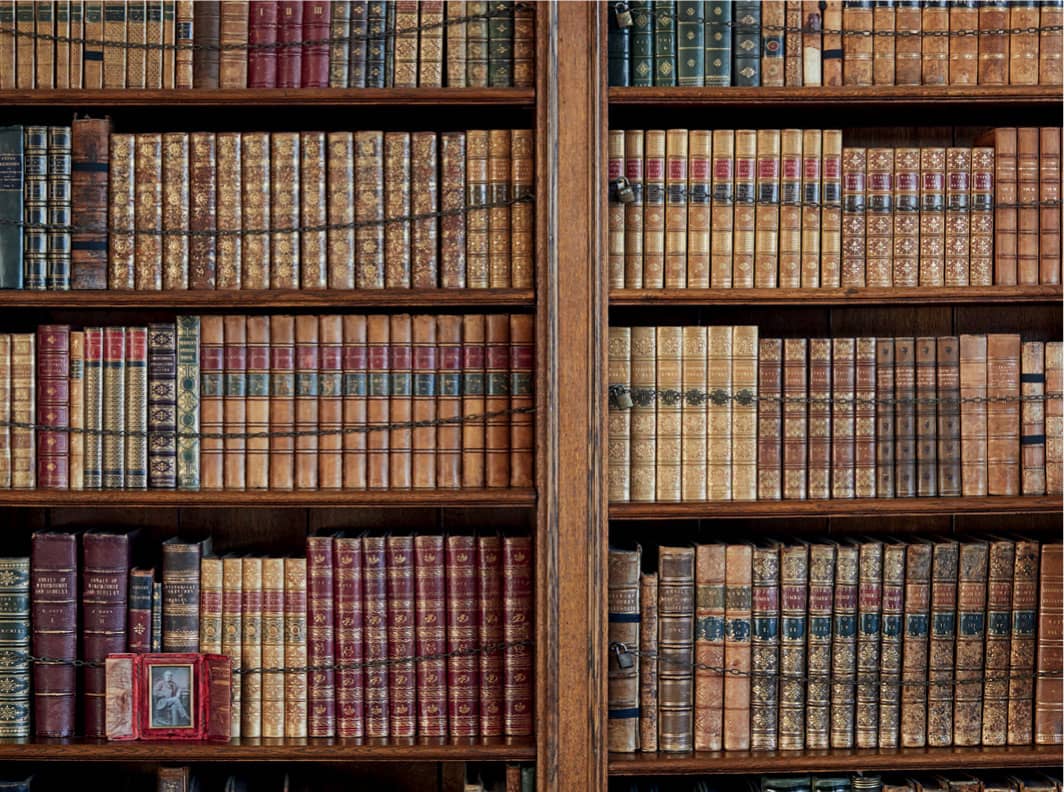

Detail of the books in the library.

The panelled library was the result of works to the house in the 1930s for the Dent-Brocklehurst family – and also used for dinner parties.

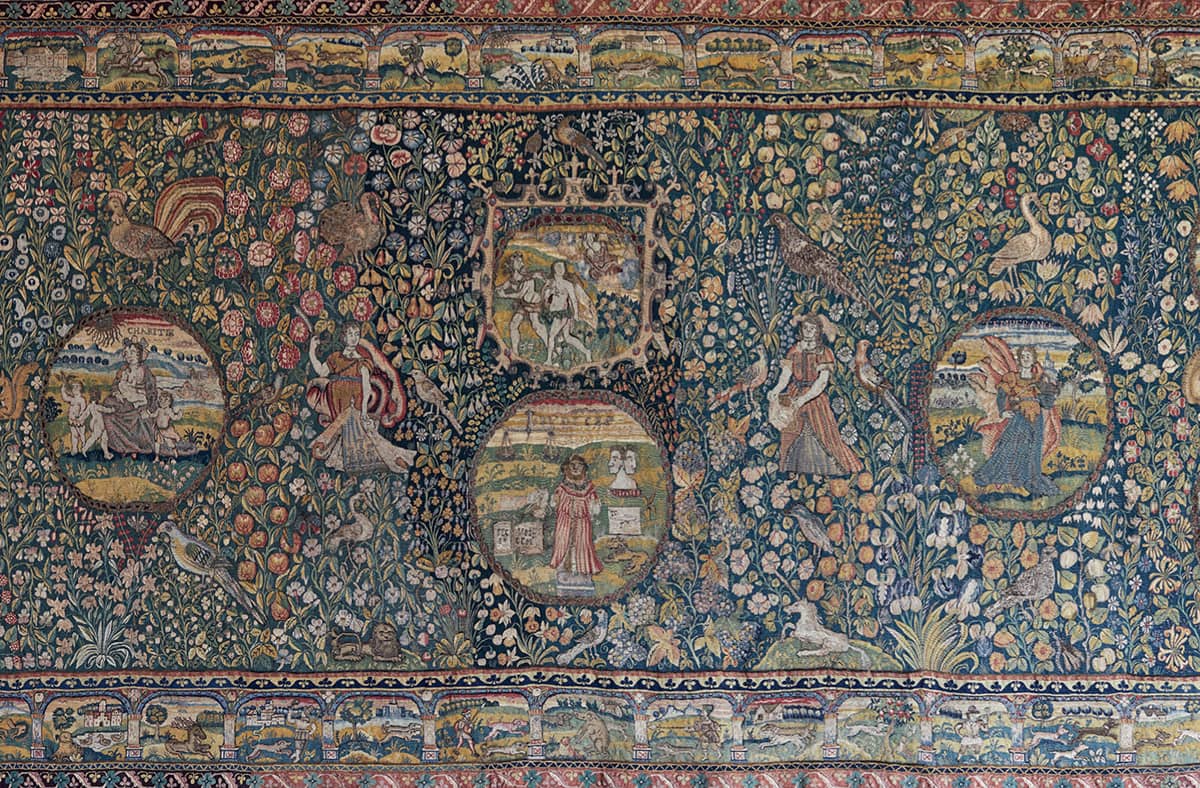

a detail of the late sixteenth-century Sheldon tapestry, which hangs in the library, depicting the expulsion of Adam and Eve from Eden.

‘It is pure theatre, which suits the house well.’

LADY ASHCOMBE

On adapting the house, she recalls: ‘We were given excellent advice from Stanley Falconer of Colefax and Fowler, who had a wonderful eye and sense of history, and designed a new staircase, as well the Gothic bookcases in our sitting room, and he also introduced the vast fireplace in this same room, which was closely modelled on the chimneypiece in the ruins of the Richard III banqueting hall.’ Many of the old master paintings now in the collection came through Mark Dent-Brocklehurst’s mother, Mary.

More recently the family has divided up the living accommodation so that Henry, Mollie and their families have their own apartments, but they all share the important larger reception rooms, such as the Stone Drawing Room on the first floor of the north range. A large part of the castle is devoted to a series of exhibition rooms for the visiting public, first designed in the 1970s by a set designer, Adam Pollock. Pollock also gave them advice on the interiors, including the removal of the Victorian panelling from the Stone Drawing Room; ‘it is all pure theatre, which suits the house well’, says Lady Ashcombe.

The theatre continues out into the gardens, which link the historic house and ruins with stylish and evocative plantings. The gardens were begun in the nineteenth century by the Dents, but have been much enhanced by additional designs in more recent times. Notable among these are the Chapel Garden, in 1979, by Rosemary Verey, and a knot garden and rose garden laid out on the original Tudor parterre by Jane Fearnley-Whittingstall, who also replanted the scheme in the East garden, which contains seventy varieties of roses, heavy with scent in summer.

Lady Ashcombe in the Stone Drawing Room.

The Chandos Bedroom, with a campaign bed owned by King Charles I.

Armorial stained glass in the Katherine Parr anteroom.

The carved bedhead of the Charles I bed.

A bust of Cromwell between two pairs of blackjacks (ale jugs in oxhide).

Stained glass.

One of the private family kitchens.

A portrait of Queen Elizabeth I in the painted glass window in the south hall.

A full-length portrait of Katherine Parr.