19

Wardington Manor

Oxfordshire

WARDINGTON MANOR in high summer feels like a house from a children’s story: rambling over different levels, cool shady rooms within, and gardens divided into room-like compartments with yew hedges and well-filled flower borders, providing plenty of opportunity for endless games of hide-and-seek. The handsome ironstone house, on the edge of the village of Upper Wardington, near Banbury, is an essentially sixteenth-century house, remodelled in the 1660s for one George Chamberlayne. But it was also extended in various ways in the early twentieth century, with contributions from Clough Williams-Ellis right at the beginning of his career, and then two arts and crafts architects, G.H. Kitchin and Randall Wells.

G.H. Kitchin had a strong interest in gardens, most memorably working with the Countess of Westmorland at Lyegrove in the 1920s. Randall Wells was a significant protégé of the arts and crafts architect W.R. Lethaby and friend of E.S. Prior, and when he died in 1942 was described as ‘one of the last representatives of that interesting school of practitioners who were content to work on almost Mediaeval principles’. With all these different interventions, the house grew from being quite a simple, linear or L-shaped plan, into an agreeable, if complex, irregular H-plan.

A sense of play

The sense of playfulness in the abundant garden continues within the house too, as the early seventeenth-century south staircase and the entrance corridor were all lovingly adorned with rippling, chevron-patterned ribs of plasterwork in the arts and crafts spirit. This was executed by the exuberant Molly Wells (formerly Lady Noble, née Mary Waters), Randall’s wife. They had met while he was remodelling another house, Besford Court in Worcestershire, owned by Molly’s first husband, Sir George Noble. Molly and Randall fell in love, and architectural works on Besford Court were abandoned because of the scandal, and Molly divorced Sir George. After she and Randall married they founded the Victoria Workshop in London together, which made furniture, fabrics and jewellery.

The landing of the main Jacobean staircase, with its exceptional 1920s plasterwork designed by Molly Wells, artist and wife of the architect Randall Wells.

The principal front of Wardington Manor seen from the field opposite

The garden front – the house was badly damaged by a fire in 2004 but expertly restored by Rodney Melville Architects.

The heart of the house: the double-height library created by arts and crafts architect G.H. Kitchin, who removed a floor level and added the oriel window facing east. The patterns of the chintz sofas are echoed by the cut flower arrangements.

A detail of the limed oak panelling in the library.

The owner of Wardington Manor from 1917, John Montie Pease (a banker and later the 1st Baron Wardington) must have had a cheerful disposition. Or perhaps he was persuaded to have one by Randall and Molly Wells, as, in addition to the grapes, fruits and grasses of the main 1920s plasterwork panels, there are various slim figures included in relief within: circus jugglers, acrobats, musicians and even an elephant holding a ball aloft in his trunk, all reminiscent of the light-hearted interwar paintings and drawings of Rex Whistler.

Molly Wells’ work was a tour de force, and gives Wardington Manor a special magic – still present nearly a century later, even though the staircase hall walls had to be partly restored after a devastating fire raged through the upper floor in 2004. The present owners, Forbes and Bridget Elworthy, originally from New Zealand, bought Wardington Manor in 2008, just as the post-fire restoration was being completed. This was being carried out by a leading conservation practice, Rodney Melville Architects, for Lady Wardington, the widow of the 2nd Lord Wardington. The restoration was faultless and the house feels discreetly but splendidly intact, with a new roof and all visible evidence of the damage removed; the main rooms, handsomely furnished and well-used, flow into each other in that seamless country-house way.

‘I feel with old houses that we are guardians of these precious things for future generations.’

BRIDGET ELWORTHY

The principal room of reception in the house is the south-facing, high-ceilinged library-come-great-hall, designed by arts and crafts architect, G.H. Kitchin, by removing the first floor from a two-storey wing of the older house, adding a handsome oriel window facing east. He fitted out the room with Jacobean-style library bookshelves, and importing an antique chimneypiece, the woodwork all limed. It was completed by Randall Wells, after Kitchin was dismissed in 1919.

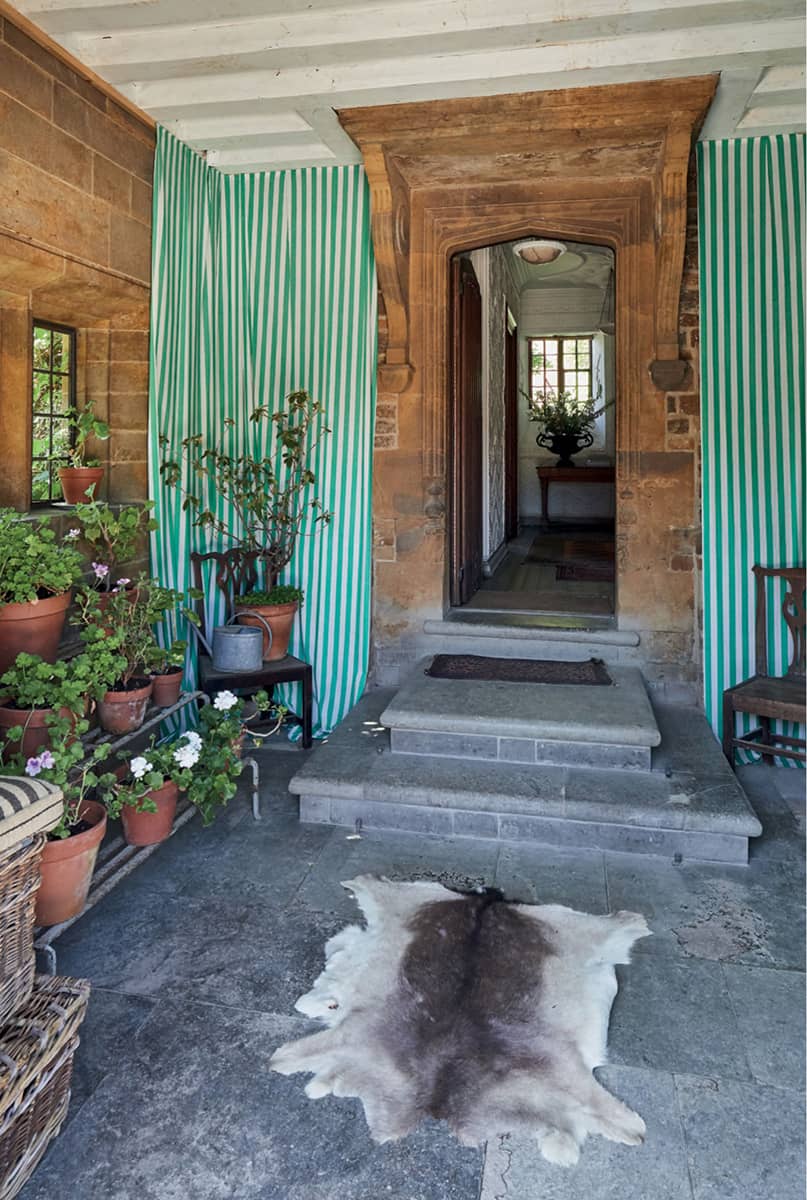

Kitchin also designed the double-storey porch on this front, which originally housed an organ, approached from the gallery of the library but which also outside forms a happy garden room framed by Tuscan columns. Wells added the two-storey gabled porch to the north-east corner of the house, and a whole new two-storey western wing, which included an arched loggia.

This loggia was enclosed by the 2nd Lord Wardington and converted to be a study-library (and remains a study and family sitting room today). The oldest easily visible parts of the house are the stone-flagged hall and the circa 1600 open-well south staircase in oak, around which Molly Wells wove her delightful web of plasterwork.

The indoor-outdoor house

The Elworthys have enjoyed inhabiting this curious hybrid house, and it is often filled with their own children and visiting friends and guests. The house seems to respond to their active and outdoor life well.

They first saw Wardington when Mr Elworthy’s career called the family back to England (all their children had been born in London). They had been living on their family farm in South Island in New Zealand, and decided to look for a house or farm in the Cotswolds area, where they could keep horses. Mrs Elworthy was shown a picture of Wardington, still then under restoration, which appealed to her, and was then introduced by a friend to the vendor Lady Wardington, who warmly encouraged them to consider buying the house – which happily had a handsome range of seventeenth-century stables which are still today in daily use.

Family life: the family kitchen with its red dresser and scrubbed pine table, and wall peppered with photographs.

The flower room.

The entrance porch hung with green striped curtain.

The overmantel of the dining room with framed ferns.

The lively chevron pattern of the 1920s plasterwork.

The oak-panelled dining room.

Forbes and Bridget Elworthy in the garden of Wardington Manor, which has inspired a new horticultural business, the Land Gardeners.

The intimate panelled sitting room hung with framed drawings and watercolours.

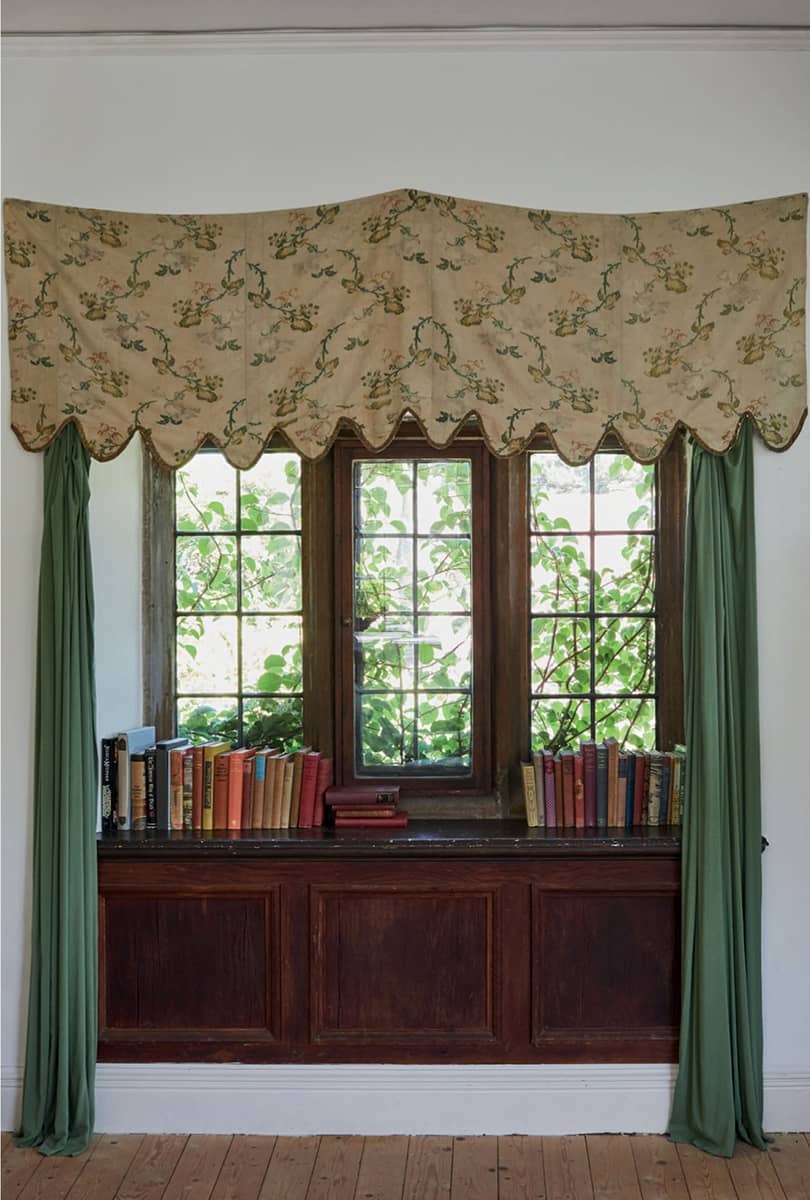

Comfortable touches: antique textiles are used for pelmets and curtains.

The stone mullioned window of the white-painted bathroom with Soane Britain fabric.

A circus perfomer in relief modelled by Molly Wells.

The circa 1600 staircase.

A four-poster bed.

A bed hung with Soane Britain floral textiles, and botanical prints on the wall.

Mrs Elworthy’s true love is the garden at Wardington, and she was clearly drawn to the generously scaled, compartmented framework, in which both Randall Wells and Clough Williams-Ellis seem to have had a hand. She has also been inspired to found a company, the Land Gardeners, with friend Henrietta Courtauld. They deliver organic cut flowers to London decorators and events, as well as designing walled and kitchen gardens, and researching ways of improving soil and plant health, encouraging gardeners to put this at the centre of their gardening life.

Mrs Elworthy’s love of the garden, nature and the country flows through the whole house, with huge flower arrangements, and curtains and upholstery in bold floral patterns inspired by traditional chintz, which come mostly from Soane Britain (run by her friend Lulu Lytle). Many of the bed hangings and curtains are old textiles collected by Mrs Elworthy, and some are old fabrics which have been re-dyed with natural dyes by Polly Lister.

Much of the furniture in the house – beds, tables and chests of drawers – was bought at Kempton antique market when they moved; more modern upholstered pieces also come from Soane Britain. The ground-floor rooms are mostly panelled, but most of the first-floor rooms are painted white, and the floorboards have been left unpainted, which gives something of a 1920s arts and crafts flavour to the house. There is also a pleasant indoor-outdoor flavour; it is not entirely a surprise to learn that on warm summer nights, sofas, armchairs and tables are pulled out from the library to continue after-dinner conversations under the stars. Of their own contribution to the house, Mrs Elworthy says: ‘I feel with old houses just the same as I do about the land; we are guardians of these precious things for future generations.’