The Same but Different

IT IS MID-JUNE, nearly solstice, and I am adding a room onto the house in West Clare. A small room only—12 by 12—enough for a bed and a bureau and a chair. P. J. Roche has put up the block walls and Des O’Shea is roofing it, after which the work inside might proceed apace—flagstones and plaster and decor. There’ll be a window to the east looking out on the haggard and a glass door to the south looking down the land, over the Shannon to Kerry rising, hilly on the other side.

It is an old house and changing it is never easy.

Near as I can figure it’s the fifth addition and will make the house nearly seven hundred square feet, adding this wee room to what is here now: an entrance hall, the kitchen, a bathroom and bedroom—my cottage in Moveen West—my inheritance.

I’m returning in a month’s time with my wife and her sister and her sister’s friend, Kitty, for a fortnight’s stay; and while the company of women is a thing to be wished for, sleeping on the sofa whilst they occupy the house’s one existing bedroom—my ancestral bedroom—is not a thing I am prepared to do.

Back in the century when this house was first built, we’d have all bedded down together maybe, for the sake of the collective body heat, along with the dog and the pig and the milch cow if we could manage it. But this is the twenty-first century and privacy is in its ascendancy.

So P. J. and I hatched this plan last year of adding a room at the east side of the house. He understands the business of stone and mortar, plaster and space, time and materials, people, place. He has reconfigured this interior before, nine years ago after Nora Lynch died.

We have settled on particulars. Gerry Lynch will help with the slates and Matty Ryan will wire things. Damien Carmody from across the road will paint. And Breda, P. J.’s wife, is the construction manager. She sorts the bills and keeps them at it. “There’s no fear, Tom,” she assures me. “It’ll all be there when you’re home in August.” There are boards and blocks and bundles of slates in the shed from Williams’s in Kilkee. We’ve been to Kilrush to order curtains and bedding from O’Halloran’s and buckets of paint from Brew’s. The place is a permanent work in progress.

MY GRANDFATHER’S grandfather, Patrick Lynch, was given this house as a wedding gift when he married Honora Curry in 1853. They were both twenty-six years old and were not among the more than a million who starved or the more than a million who left Ireland in the middle of the nineteenth century in what today would be called a Holocaust or Diaspora but in their times was called the Famine.

On the westernmost peninsula of this poor county, in the bleakest decade of the worst of Irish centuries, Pat and Honora pledged their troth and set up house here against all odds. Starvation, eviction, and emigration—the three-headed scourge of English racism by which English landlords sought to consolidate smaller holdings into larger ones—had cut Ireland’s population by a quarter between 1841 and 1851. Tiny parcels of land and a subsistence diet of potatoes allowed eight Lynch households to survive in Moveen, according to the Tithe books of 1825. Of these eight, three were headed by Patricks, two by Daniels, and there was one each by Michael and Anthony and John. One of these men was my great-great-great grandfather. One of the Patricks or maybe a Dan—there’s no way of knowing now for certain. Their holdings ranged from three acres to nearly thirty. Of the eleven hundred acres that make up Moveen West, they were tenants on about a tenth. They owned nothing and were “tenants at will”—which is to say, at the will of a gentrified landlord class who likely never got closer to Moveen than the seafront lodges of Kilkee three miles away, always a favorite of Limerick Protestants. Their labor—tillage and pasturage—was owned by the landlord. The Westropps owned most of these parts then—James and John and later Ralph. The peasants were allowed their potatoes and their cabins. Until, of course, the potato failed. Of the 164 persons made homeless by the bailiffs of John Westropp, Esq., in May of 1849, in Moveen, thirty were Lynches. All of Daniel Lynch’s family and all of his son John’s family were evicted. The widow Margaret Lynch was put out of her cabin and John Lynch the son of Martin was put off of his nine acres. Another John Lynch could not afford the seven pounds, ten shillings rent on his small plot. The roofs were torn from their houses, the walls knocked down, their few possessions put out in the road. The potato crop had been blighted for four out of the last five years. Some of the families were paid a pittance to assist with the demolition of their homes, which made their evictions, according to the landlord’s agents, “voluntary.” Along with the Lynches evicted that day were Gormans and McMahons, Mullanys and Downses—the poor cousins and sisters and brothers of those marginally better situated economically or geographically who were allowed to stay but were not allowed to take them in. It was, for the class of landlords who owned the land, a culling of the herd of laboring stock, to make the ones who were left more fit, more efficient laborers. For those evicted, it was akin to a death sentence. For those who stayed, it was an often-toxic mix of survivors’ pride, survivors’ guilt, survivors’ shame. Like all atrocities, it damns those who did and those who didn’t. Like every evil, its roots and reach are deep.

In proportion to its population, County Clare had the highest number of evictions in all of Ireland for the years 1849 through 1854. The dispossessed were sent into the overcrowded workhouse in Kilrush, or shipped out for Australia or America or died in a ditch of cholera or exposure. As John Killen writes in the introduction to The Famine Decade, “That a fertile country, the sister nation to the richest and most powerful country in the world, bound to that country by an Act of Union some forty-five years old, should suffer distress, starvation and death seems incomprehensible today. That foodstuffs were exported from Ireland to feed British colonies in India and the sub-continent, while great numbers of people in Ireland starved, beggars belief.”

But the words George Bernard Shaw puts into the mouths of his characters in Man and Superman get at the truth of it:

MALONE: My father died of starvation in Ireland in the Black ’47. Maybe you heard of it?

VIOLET: The famine?

MALONE (with smoldering passion): No, the starvation. When a country is full of food, and exporting it, there can be no famine.

The words of Captain Arthur Kennedy, the Poor Law inspector for the Kilrush Union who meticulously documented the particulars of the horror in West Clare, are compelling still:

The wretchedness, ignorance, and helplessness of the poor on the western coast of this Union prevent them seeking a shelter elsewhere; and to use their own phrase, they “don’t know where to face”; they linger about the localities for weeks or months, burrowing behind the ditches, under a few broken rafters of their former dwelling, refusing to enter the workhouse till the parents are broken down and the children half starved, when they come into the workhouse to swell the mortality, one by one. Those who obtain a temporary shelter in adjoining cabins are not more fortunate. Fever and dysentery shortly make their appearance when those affected are put out by the roadside, as carelessly and ruthlessly as if they were animals; when frequently, after days and nights of exposure, they are sent in by relieving officers when in a hopeless state. These inhuman acts are induced by the popular terror of fever. I have frequently reported cases of this sort. The misery attendant upon these wholesale and simultaneous evictions is frequently aggravated by hunting these ignorant, helpless creatures off the property, from which they may perhaps have never wandered five miles. It is not an unusual occurrence to see 40 or 50 houses leveled in one day, and orders given that no remaining tenant or occupier should give them even a night’s shelter.

The evicted crowd into the back lanes and wretched hovels of the towns and villages, scattering disease and dismay in all directions. The character of some of these hovels defies description. I, not long since, found a widow whose three children were in fever, occupying the piggery of their former cabin, which lay beside them in ruins; however incredible it may appear, this place where they had lived for weeks, measured 5 feet by 4 feet, and of corresponding height. There are considerable numbers in this Union at present houseless, or still worse, living in places unfit for human habitation where disease will be constantly generated.

The mid-nineteenth-century voice of Captain Kennedy, like mid-twentieth-century voices of military men proximate to atrocity, seems caught between the manifest evil he witnesses and the duty to follow orders he has been given.

I would not presume to meddle with the rights of property, nor yet to argue the expediency or necessity of these “monster” clearances, both one and the other no doubt frequently exist; this, however, renders the efficient and systematic administration of the Poor Law no less difficult and embarrassing. I think it incumbent on me to state these facts for the Commissioners’ information, that they may be aware of some of the difficulties I have to deal with. —Reports and Returns Relating to Evictions in the Kilrush Union: Captain Kennedy to the Commissioners, July 5, 1848

IT WAS A starvation, a failure of politics more than crops that cleared the land of the poor, killed off thousands in the westernmost parishes, and dispersed the young to wander the world in search of settlements that could support them.

Moveen, of course, was never the same.

By August of 1855, when Griffith’s Valuation was done, only three households of Lynches remained in Moveen—Daniel Lynch, the widowed Mary Lynch, and the lately married Patrick Lynch. It was Mary who gave Patrick and Honora their start, putting in a word for her son with the landlord and making what remained of the deserted cabin habitable.

My guess is Honora came from an adjacent townland, nearer the Shannon—Kilfearagh maybe, or Lisheen where her famous granduncle Eugene O’Curry, the Irish language scholar, came from; or north of here, toward Doonbeg, where the Currys were plentiful in those days. Maybe her people and Pat’s people were both from the ancient parish of Moyarta and it is likely they met at church in Carrigaholt or in one of the hedge schools.

Pat came out of the house above, on the hill where the land backs up to the sea, where James and Maureen Carmody live now with their daughter Rachel and their son, Niall. James would be descended from Pat’s brother, Tom; and, of course, from Mary, the widowed mother. We’d all be cousins many times removed.

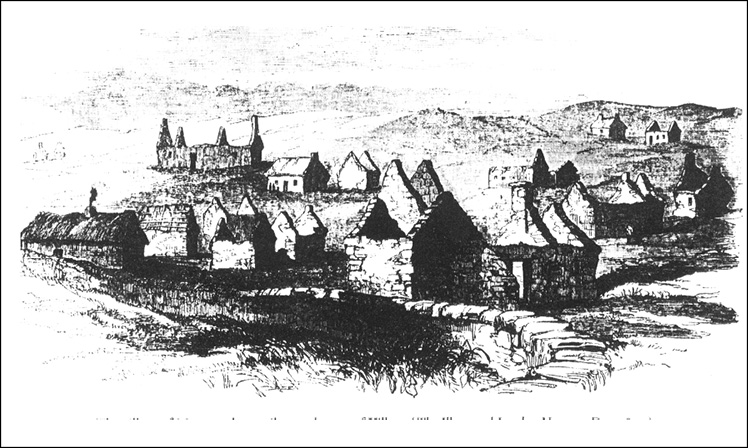

The newlyweds leased twenty-six acres from Ralph Westropp, the English landlord. The house had, according to the records, “stone walls, a thatched roof, one room, one window and one door to the front.” In the famous illustration of “Moveen after the Evictions,” which appeared in the Illustrated London News on December 22, 1849, there are sixteen cottages of this kind, most of them roofless, their gables angled into the treeless hillocks of Moveen, their fires quenched, their people scattered to Liverpool and the Antipodes and the Americas. In 1855, the Griffith Valuation assigned the place a tax rate of ten shillings. The more windows and doors a house had, the more the tax. No doubt to accommodate their ten children, Pat added a bedroom to the south.

On October 3, 1889‚ Honora died. She was buried in the great vault at Moyarta, overlooking the Shannon and the estuarial village of Carrigaholt. Hers was a slow death from stomach cancer, giving time for her husband and his brother Tom to build the tomb, there near the road, with its cobblestone floor, tall gabled end‚ and huge flagstone cover that was inscribed with her particulars by Mick Troy, the stonecutter from Killballyowen, famous for his serifs and flourishes. The brother Tom lost an eye to the tomb’s construction when a chunk of stone flew off of Pat’s sad hammering. The work must have taken most of a month—to bring the round gray rocks up from the Shannon beach by the cartload for the floor, ledge rocks from the cliff’s edge to line the deep interior and build the gable he would plaster over‚ and finally the massive ledger stone that would serve as tomb roof and permanent record. Grave work, in anticipation of his grief—the larger muscles’ indenture to the heart—it was all he could do for the dying woman.

For months after his mother’s death, my great-grandfather, looking out the west window of this house at the mouth of the River Shannon and the sea beyond, must have considered the prospects for his future. As ever in rural Ireland there were no guarantees. The labor and poverty were crushing. Parnell and land reform were distant realities. Their lease on the land would support just one family. A sister Ellen had gone off to Australia. A brother Michael married in a hurry when he impregnated a neighbor girl and moved far away from the local gossip, first to Galway and then to a place in America named Jackson, Michigan. Another brother, Pat, passed the exam to become a teacher but the Kilkee School already had a teacher, so he was given an offer in The North. His mother, Honora, had forbidden his going there, fearful for his soul among Protestants, so Pat sailed off to Australia to find his sister Ellen in Sydney. He was said to be a wonderful singer. “But for Lynch, we’d all do‚” is what was said about him after he’d regaled his fellow passengers on the long journey. He was, it turned out, good at seafaring too, keeping logs and reading the stars and charts. The captain of the ship offered him work as a first mate and it is rumored that after a fortnight’s visit with his sister in Sydney, he returned to the ship and spent the rest of his days at sea. No one in Moveen ever heard from him again. He famously never sent money home. Dan and John, two other brothers, had died young‚ which left Tom and Sinon and their sister Mary who was sickly and their widowed father still at home.

Tom Lynch booked passage for America. He was twenty-four. I’m guessing he sailed from Cappa Pier in Kilrush and went through Canada, working his way from Quebec to Montreal to Detroit and then by train out to Jackson. He settled in a boardinghouse near his brother Michael and the wife, Kate, there in Jackson—a place their father, Pat, had been to briefly years before—where a huge state prison and the fledgling auto shops promised work. Maybe it was in memory of his dead mother, or maybe because there was a space on the forms, or maybe just because it was the American style, he identified himself in his new life in the new world as Thomas Curry Lynch. Or else it was to distinguish himself from the better-known and long-established Thomas B. Lynch, proprietor, with Cornelius Mahoney, of Jackson Steam Granite Works, “Manufacturers of Foreign and Domestic Monuments‚” situated on Greenwood Avenue, opposite the cemetery. Maybe to better his job prospects or his romantic ones, he shaved four years off his age in the same way. Among his new liberties was to identify himself as he saw fit. The stone in Jackson in St. John’s Cemetery maintains his version of it. Thomas C. Lynch, it reads, 1870–1930. Back at the Parish House in Carrigaholt, his baptism is recorded in 1866.

Before he was buried in Jackson, in consort with Ellen Ryan, the Canadian daughter of Irish parents, to whom he was married in 1897, Thomas Curry Lynch fathered a daughter, Gertrude, who became a teacher, and two sons: Thomas Patrick who would become the priest I’d be named for, and Edward Joseph who would become my grandfather.

According to the Jackson City Directory, Thomas Curry Lynch worked as a “fireman‚” a “helper‚” a “laborer‚” a “painter,” a “foundry man‚” and as a “janitor” at I. M. Dach Underwear Company. In September 1922, he was hired as a guard for the Michigan State Prison in Jackson. The picture on his employee pass shows a bald man with a long‚ square face in a three-piece double-breasted suit and white shirt, collar pin and tie. He is looking straight into the camera’s eye, neither smiling nor frowning; his closed mouth is a narrow level line between a good nose and a square chin—a sound man, as they say in Clare, able and airy and dressed to the nines. He bought a small frame house at 600 Cooper Street, a block south of St. John’s Church, outlived his wife by nine years‚ and died in September of 1930. He never lived to see his son receive his Holy Orders in 1934 or die of influenza in 1936. He is buried there in Jackson among the Morrisseys and Higginses and others from the western parishes of Clare, between Ellen and his youngest son. He rests in death, as in life, as Irish men have often done, between the comforts and vexations of priest and the missus, far from the homes they left as youths.

SINON, THE BROTHER Tom had left at home, stayed on and kept his widowed father. In 1895 he married Mary Cunningham from Killimer, east of Kilrush, and they raised sons and daughters, the youngest of whom, Tommy and Nora, born in 1901 and 1902, waited in the land and tended to their aging parents and kept this house.

The census of a hundred years ago records a house with stone walls, a thatched roof, two rooms, two windows‚ and a door to the front. Early in the twentieth century‚ another room was added to the north and divided by partition into two small rooms. So there was a room for the parents, a room for the girls, a room for the boys‚ and a room for them all where the table and the fire were. The farm, at long last, was a freehold, the first in the townland, bought from the landlord in 1903 under the provisions of the Land Purchase Act. Cow cabins and out-offices appeared‚ and a row of whitethorns that Pat Lynch had planted years before to shelter the east side of the house were now full grown. He bought them as saplings in Kilrush when he’d gone there for a cattle fair. He paid “two and six”: two shillings and sixpence, about thirty cents, and brought them home as a gift for Honora who had them set beside some native elder bushes. They still provide shelter and berries for birds.

This is how I found it when I first came here—sheltered by whitethorns and elders on the eastern side, stone walls, stone floors, thatched roof, an open hearth with the fire on the floor, a cast-iron crane and hooks and pots and pans and utensils. There were three windows and one door to the front, three windows and a door to the back, four lightbulbs, strung by wires, one in every room, the kitchen at the center, the bedroom to the south, and two smaller rooms, divided by a partition, to the north. There was a socket for the radio perched in the deep eastern window, a socket for the kettle and the hotplate, and a flickering votive light to the Sacred Heart. There were pictures of Kennedy and the pope, Jesus crowned with thorns, the Infant of Prague, St. Teresa, St. Martin de Porres, and a 1970 calendar from Nolan’s Victuallers. There was a holy-water font at the western door. The mantel was a collection of oddments—a wind-up clock, a bottle of Dispirin, some antiseptic soap, boxes of stick matches from Maguire & Patterson, plastic Madonnas and a bag of sugar, a box of chimney-soot remover called Chimmo, and cards and letters, including mine. There was a flashlight‚ and a tall bottle of salt and a bag of flour. Otherwise the house remained unencumbered by appliance or modernity—unplumbed, unphoned, dampish and underheated, unbothered by convenience, connection‚ or technology. It resembled, in its dimensions, the shape of a medieval coffin or an upturned boat, afloat in a townland on a strip of land between the mouth of the Shannon and the North Atlantic. It seemed to have as much in common with the sixteenth century as the twentieth. Perpendicular to the house on the south side was a cow cabin divided into three stalls, each of which could house half a dozen cows. On the north side of the house, also perpendicular, was a shed divided into two cabins. Hens laid eggs in the eastern one. In the western one was turf.

Last week for the first time in more than thirty years, I could see it all—as the Aer Lingus jet made its descent from the northwest, over the Arans to the Shannon Estuary, the cloud banks opened over the ocean, clear and blue from maybe 5,000 feet, and I could see the whole coastline of the peninsula, from the great horseshoe strand at Kilkee out the west to Loop Head. The DC-9 angled over Bishop’s Island, Murray’s Island, and Dunlicky, the cliffs and castle ruins, and the twin masts atop Knocknagaroon that the pilots aim for in the fog. I could see the quarry at Goleen and the Holy Well and James and Maureen Carmody’s house on the hill and Patrick and Nora Carmody’s, Jerry Keane’s and J. J. McMahon’s, and Sonny and Maura Carmody’s and the Walshes’ and Murrays’ and there, my own, this house and the haggard and the garden and outbuildings and the land and the National School and Carrigaholt Castle and banking eastward Scattery Island and the old workhouse in Kilrush and the ferry docks at Tarbert and then, in a matter of minutes, we landed.

I never saw it so clearly before. The first time I came here, it was just a patchwork of green emerging from the mist, the tall cliffs, ocean, river, houses, lands.

Nothing had prepared me for such beauty.

I was the first of my people to return.

My great-grandfather, Thomas Curry Lynch, never returned to this house he was born in nor ever saw his family here again. My grandfather, Edward, proud to be Irish, nonetheless inherited the tribal scars of hunger and want, hardship and shame, and was prouder still to be American. He never made the trip. He worked in parcel post at the Main Post Office in Detroit, wore a green tie on St. Patrick’s Day, frequented the bars on Fenkell Avenue until he swore off drink when my father went to war and spoke of Ireland as a poor old place that couldn’t feed its own. And though he never had the brogue his parents brought with them, and never knew this place except by name, he included in his prayers over Sunday dinners a blessing on his cousins who lived here then, “Tommy and Nora,” whom he had never met, “on the banks of the River Shannon,” which he had never seen, and always added, “Don’t forget.”

Bless us, O Lord

And these thy gifts

Which we are about to receive

From thy bounty

Through Christ Our Lord.

Amen.

And don’t forget your cousins

Tommy and Nora Lynch

On the banks of the River Shannon.

Don’t forget.

The powerful medicine of words remains, as Cavafy wrote in his poem “Voices”:

Ideal and beloved voices

of those dead, or of those

who are lost to us like the dead.

Sometimes they speak to us in our dreams;

sometimes in thought the mind hears them.

And with their sound for a moment return

other sounds from the first poetry of our life—

like distant music that dies off in the night.

And this is how my grandfather’s voice returns to me now—here in my fifties, and him dead now “with” forty years (in Moveen life and time go “with” each other)—“like distant music that dies off in the night,” like “the first poetry of our life.”

Bless us, O Lord.

Tommy and Nora.

Banks of the Shannon.

Don’t forget. Don’t forget.

He is standing at the head of the dining-room table in the brown brick bungalow with the green canvas awning on the porch overlooking Montavista Street two blocks north of St. Francis de Sales on the corner of Fenkell Avenue in Detroit. It is any Sunday in the 1950s and my father and mother and brothers, Dan and Pat and Tim, are there and our baby sister, Mary Ellen, and Pop and Gramma Lynch and Aunt Marilyn and Uncle Mike and we’ve been to Mass that morning at St. Columban, where Fr. Kenny, a native of Galway, held forth in his flush-faced brogue about being “stingy with the Lord and the Lord’ll be stingy with you,” and we’ve had breakfast after Mass with the O’Haras—our mother’s people—Nana, and Uncle Pat and Aunt Pat and Aunt Sally Jean and Uncle Lou, and then we all piled in the car to drive from the suburbs into town to my father’s parents’ house for dinner. And my grandfather, Pop Lynch, is there at the head of the dining-room table, near enough the age that I am now, the windows behind him, the crystal chandelier, all of us posing as in a Rockwell print—with the table and turkey and family gathered round—and he is blessing us and the food and giving thanks and telling us finally, “Don’t forget” these people none of us has ever met, “Tommy and Nora Lynch on the banks of the River Shannon. Don’t forget.”

This was part of the first poetry of my life—the raised speech of blessing and remembrance, names of people and places far away about whom and which we knew nothing but the sounds of the names, the syllables. It was the repetition, the ritual almost liturgical tone of my grandfather’s prayer that made the utterance memorable. Was it something he learned at his father’s table—to pray for the family back in Ireland? It was his father, Thomas Lynch, who had left wherever the banks of the Shannon were and come to Jackson, Michigan, and painted new cellblocks in the prison there and striped Studebakers in an auto shop there. Was it that old bald man in the pictures with the grim missus in the high-necked blouse who first included in the grace before meals a remembrance of the people and the place he’d left behind and would never see again?

Bless us O Lord, Tommy and Nora. Banks of the Shannon.

Don’t forget.

When I arrived in 1970, I found the place as he had left it, eighty years earlier, and the cousins we’d been praying for all my life. Tommy was holding back the barking dog in the yard. Nora was making her way to the gate, smiling and waving, all focus and calculation. They seemed to me like figures out of a Brueghel print: weathered, plain-clothed, bright-eyed, beckoning. Words made flesh—the childhood grace incarnate: Tommy and Nora. Don’t forget. It was wintry and windy and gray, the first Tuesday morning of the first February of the 1970s. I was twenty-one.

“Go on, boy, that’s your people now,” the taxi man who’d brought me from Shannon said. I paid him and thanked him and grabbed my bag.

I’VE BEEN COMING and going here ever since.

The oval welcome in my first passport—that first purple stamp of permission—remains, in a drawer in a desk with later and likewise-expired versions. 3 February 1970. Permitted to land for 3 months.

The man at the customs desk considered me, overdressed in my black suit, a jet-lagged dandy with his grandfather’s pocket watch, red-eyed, wide-eyed, utterly agape. “Gobsmacked,” I would later learn to call this state.

“Anything to declare?” he asked, eyeing the suitcase and the satchel.

“Declare? Nothing.”

“Passport.” I handed it over.

“The name’s good,” he said, and made an “X” on my luggage with a piece of chalk. “You’re welcome home.”

I walked through customs into the Arrivals Hall of Shannon Airport. At the Bank of Ireland window I traded my bankroll of one hundred dollars for forty-one Irish punts and change—huge banknotes, like multicolored hankies folded into my pocket. I walked out into the air sufficiently uncertain of my whereabouts that when a taxi man asked me did I need a lift, I told him yes and showed him the address.

“Kilkee—no bother—all aboard.”

That first ride out to the west was a blur. I was a passenger on the wrong side of a car that was going way too fast on the wrong side of roads that were way too small through towns and countryside that were altogether foreign. Cattle and parts of ruined castles and vast tracts of green and towns with names I’d seen on maps: Sixmilebridge, Newmarket on Fergus, Clarecastle, then Ennis where the signpost said, Kilkee 35 miles, then Kilrush, where another said, Kilkee 8.

“How long are you home for?” the driver asked. I’d never been so far from home before.

“I don’t know,” I told him. I didn’t know. I didn’t know what “home” meant to the Irish then, or what it would come to mean to me. I’d paid two hundred and nineteen dollars for a one-way ticket from Detroit to New York to Shannon. I had my future, my passport, my three months, no plans.

The ride from Shannon took about an hour.

What a disappointment I must have been—deposited there in the road outside the gate, the Yank, three generations late, dressed as if for a family photo, fumbling with a strange currency for the five-pound note I owed for the ride, bringing not the riches of the New World to the Old, but thirty-six pounds now and a little change, some duty-free tobacco and spirits, and the letter that Nora Lynch had sent that said it was all right for me to come. Blue ink on light blue lined paper, folded in a square, posted with a yellow stamp that bore a likeness of “Mahatma Gandhi 1869–1948” and a circular postmark: CILL CHADIOHE CO AN CHLAIR, which I later learned to English as “Kilkee, Co. Clare.” The handwriting was sturdy, angular, and stayed between the lines.

Moveen West

Kilkee

Jan 8. ’70

Dear Thomas

We received your letter before Xmas. Glad to know you are coming to Ireland. At the moment the weather is very cold. January is always bad. I hope it clears up before you land. Write and say when you expect to come so we’d get ready for you. I hope all your family are well.

With Best Regards to All the Lynch’s

Nora & Tom

Of course she hadn’t a clue about us—“All the Lynch’s,” as she called us. Whatever illusions Americans have about the Irish—that they are permanently good-natured, all saints and scholars, tidy and essentially well-intentioned drunks, cheerful brawlers—all that faith-and-begorra blindness behind The Quiet Man and the Irish Spring commercials, what the Irish knew about Americans was no less illusory.

The taxi man told me a joke en route, about the “Paddy” he called him, from Kilmihil, who’d gone off to the States to seek his fortune, having heard that the money there grows on trees and the streets are “literally paved with it,” et cetera, and “he’s after stepping off the boat in Boston of a Sunday and making his way up the road when what does he see but a ten-dollar bill in the street, plain as day. And your man, you know, is gobsmacked by the sight of it, and saying to himself, ‘The boyos back home were right after all, this place is nothing but money, easy as you please,’ and he bends to pick up the tenner when the thought comes to him. He straightens up, kicks it aside, and says to himself, ‘Ah hell, it’s Sunday. I’ll start tomorrow.’”

Still Nora Lynch would have known I was one of her people. She would have sorted out that her grandfather was my grandfather’s grandfather. Old Pat Lynch, whose heart failed at eighty on the twelfth of June in 1907, would be our common man. His body buried with his wife’s, long dead, and Nora’s twin who had died in infancy of encephalitis, and Nora’s father who had died in 1924—all of them returning to dust in the gabled tomb by the road in Moyarta. We’d be cousins, so, twice removed. She could twist the relations back the eighty years, back to the decade before she was born when her father’s brother Tom left for America. Old Pat had gone to America himself years before, stayed for several months, and returned to Honora and the children. Maybe he was the one who discovered Jackson, Michigan, and the huge prison, opened in 1838, the largest in the world back then, and all the work it provided for guards and cooks and the building trades. And Nora’s brother Michael had gone to Jackson as a young man, following others from the west of Clare to “Mitch-e-gan.” The records at Ellis Island show him landing there in 1920, off the Adriatic from Southampton. He’d married there and when his wife died, he returned to Moveen, where he died of a broken heart one warm August day in 1951 while saving hay. Nora would have had word from him about the Jackson crowd—about their uncle, Thomas Curry Lynch, and his wife, “a Ryan woman, wasn’t she?” and about his boys, Eddie and Tommy, and their sister Gertrude, raised at 600 Cooper Street. Hadn’t he brought a picture of his first cousin the priest, Fr. Thomas Patrick Lynch, for whom I’d be named a dozen years after the young priest had died—my father’s uncle—there in the wide-angled photo of them all gathered out front of St. John’s Church on Cooper Street in Jackson, Michigan, in June of 1934 shortly after his ordination. My father, ten years old, wearing knickers and knee socks, is seated between his father and mother. And Nora’s brother Mikey, somewhere in that crowd, posed for the camera with his young wife who would be dead before long, the way they are all dead now. Nora and Tommy four thousand miles away, in the prime of their lives, will get word from one of them, about the new priest in the family.

And years later she will sort it all out: her Uncle Thomas married Ellen Ryan, “a great stiff of a woman,” she had heard, and their son, Edward, married Geraldine, “some shape of a Protestant, but she converted,” and their son Edward married Rosemary, and then this Yank, twentyish, out of his element, in the black suit standing in the rain at the gate, the dog barking, the cab disappearing down the road, all family, “all the Lynch’s,” all long since gone, and now returned.

“So, Tom that went,” she said, connecting eight decades of dates and details, “and Tom that would come back. You are welcome to this part of the country.”

After the dog, Sambo, was subdued, we went indoors. There was a fire on the floor at the end of the room, a wide streak of soot working up the wall where the chimney opened out to the sky. And the rich signature aroma of turf smoke I’d smelled since landing in Shannon. I was given a cigarette, whiskey, a chair by the fire, the household luxuries.

“Sit in there now, Tom. You’ll be perished with the journey,” Tommy said, adding black lumps to the fire. “Sure faith, it’s a long old road from America.” There were odd indecipherable syllables between and among the words I could make out.

Nora was busy frying an egg and sausage and what she called “black pudding” on the fire. She boiled water in a kettle, cut bread in wedges from a great round loaf, pulled the table away from the wall into the middle of the room, settled a teapot on some coals in front of the fire. She set out cups and plates and tableware. Tommy kept the fire and interrogated me. How long was the trip, how large the plane, were there many on it, did they feed us well? And my people would be “lonesome after” me. I nodded and smiled and tried to understand him. And there was this talk between them, constant, undulant, perfectly pitched, rising and falling as the current of words worked its way through the room, punctuated by bits of old tunes, old axioms, bromides, prayers, poems, incantations. “Please Gods” and “The Lord’ve mercies” and “The devil ye know’s better than the one ye don’t”—all given out in a brogue much thicker and idiomatically richer than I’d ever heard. They spoke in tongues entirely enamored of voice and acoustic and turn of phrase, enriched by metaphor and rhetoricals and cadence, as if every utterance might be memorable. “The same for some, said Jimmy Walsh long ’go, and the more with others.” “Have nothing to do with a well of water in the night.” “A great life if you do not weaken.” There was no effort to edit, or clip, or hasten or cut short the pleasure of the sound words made in their mouths and ears. There were “Sure faith’s” and “Dead losses” and “More’s the pities.” And a trope that made perfect sense to Nora, to wit: “The same but different”—which could be applied to a variety of contingencies.

“The same but different,” she said when she showed me the wallpaper she’d lately pasted to the freshly plastered walls of the room she had prepared for me. “The same as America, but different.” There was a narrow bed, a chair on which to put my suitcase, a crucifix, and the picture of the dead priest I’d been named for. The deep window ledge gave me room for my briefcase. There was a chamber pot on the floor and a lightbulb hung from the ceiling. The room was five feet wide and ten feet long, like a sleeper on a night train or a berth in steerage class, snug and monkish, the same but different.

After tea she took me down in the land. Out past the cow cabins and the tall hay barn, we stepped carefully along a path of stones through the muddy fields. Nora wore tall rubber boots she called Wellingtons and moved with a deliberate pace along the tall ditch banks that separated their land from the neighbors’. She carried a plastic bucket. She seemed immediately and especially curious about my interest in farming. I told her I didn’t know a thing about it. “There’s nothing to it,” she told me. “You’ll have it learned like a shot. A great block of a boy like you, it’ll be no bother for ye. You’d get a tractor, and a wife, and there’d be a good living in it.”

“What do you grow?” I asked her.

“Mostly cows.”

We made our slow way down the soggy land, dodging pools of standing water and thickening mud.

“Mind the fort, Tom,” Nora said, pointing to a tall, circular mound that occupied the corner of the next field over. “Never tamper with a fort.”

Then she knelt to an open well in the middle of the land, skimmed the surface with the bucket, then sank it deep and brought it up again with clear water spilling over the edges.

“Have a sup, Tom, it’s lovely water and cold and clean.”

We walked the half a mile uphill back to the house. I carried the bucket and was highly praised for doing so.

Back at the fire, Nora told me how she and Tommy had been the youngest of their family. How her father died young and all their siblings had left for America except for Nora’s twin brother who died in infancy. Two sisters had gone to Buffalo, New York, married well, and never returned. Mikey had gone to Jackson, “Mitch-e-gan,” and worked there in the factory and married but his wife died young and he came home to Moveen and died saving hay in the big meadow in 1951. He was fifty-three. So it fell to Tommy and Nora to keep the place going and care for their widowed mother who was always sickly and feeble. Neither married, though they had many chances, “you can be sure of that, Tom.” Both had stayed. Now, nearing seventy, they had their health, their home, and their routine. “Thanks be to God,” they wanted for nothing. God had been good to them. “All passing through life.” Sambo dozed in the corner. A cat curled on the window ledge. Another nursed her litter in the clothes press near the fire. There was a goose in the storage room waiting on an egg. There was rain at the windows, wind under the doors. The clock on the mantel was ticking. The day’s brief light was fading rapidly. The coals reddened in the fire on the floor.

Now I was nodding, with the long journey and the good feed and the warmth of the fire at my shins, and the chanting of cattle in the adjacent cabin and the story Nora was telling me of lives lived out on both sides of the ocean—an ocean I’d seen for the first time that day. I might’ve drifted off to sleep entirely, awash in bucolia, talk, and well-being, if all of a sudden Tommy didn’t rise, tilt his head to some distant noise, haul on his tall boots, and disappear out the door. Nora quickly filled a large pot with water and hung it from the crane over the fire. She brought lumps of coal from a bag in the storage room and added them to the turf. She rolled a piece of newspaper and fanned the coals to flames in the turf. She brought a bucket of meal from a tall bag in the same room. I wondered what all of the bustle was about.

Within moments, Tommy was back in the door holding in a slippery embrace a calf still drenched with its own birthing. It was the size of a large dog, and shaking and squirming in Tommy’s arms. Nora mixed meal in a large plastic bowl and filled it with boiling water—a loose oatmeal that she took out to the cow cabin. Tommy dried the new calf with straw and kept it close to the warm fire and tried to get it to suckle from a bucket of milk and meal. “Fine calf, a fine bullock God bless ’oo,” he kept repeating, “that’s it now, drink away for yourself.” Nora reappeared and disappeared again with another bucket of hot meal. All of this went on for most of an hour. The calf was standing now on its own spindly legs. Tommy took it out to suck from its mother. It was dark outside; the night was clear and cold. The cow cabin, though it stank of dung, was warm with the breath of large bodies. Tommy squirted the new calf from its mother’s teat and said, “Go on now, go on now, sup away for yourself, best to get the beastings right away, there’s great medicine in the first milk.” He got hay from the hay barn and spread it about and traded one of his Woodbines for my Old Gold. We stood and smoked and watched the new bullock suckle, its mother licking it with great swipes of her tongue.

“Haven’t they great intelligence after all?” said Tommy. “That’s it then, Tom, we’ll go inside.”

I was chilled and tired, tired to the bone. But Nora made fresh tea and put out soda bread and cookies and praised the good fortune of a healthy calf, God bless him, and Tommy who was a “pure St. Francis” with the animals. “None better. Ah, no boy. Of that you can be sure.” Then she filled an empty brown bottle with boiling water and put it in my bed to warm the sheets. She brought out blankets and aired them by the fire then returned them to the room I was given to sleep in. I crawled in and despite the cold and damp could feel my body’s heat beneath the heavy bed linens and was soon asleep.

Sometime in the middle of that first night I woke, went out the back door to piss the tea and water and whiskey in the dark, and looking up I saw a firmament more abundant than anything I’d ever seen in Michigan. It was, of course, the same sky the whole world sees—the same but different—as indeed I felt myself to be, after that first night on the edge of Ireland, in the townland of Moveen with the North Atlantic roaring behind the fields above, and the house full of its nativities, and the old bachelor and his spinster sister sleeping foot-to-foot in their twin beds and common room and myself out pissing under the stars asking the heavens how did I ever come to be here, in this place, at all?

IN THE LATE 1960s, my life was, like the lives of most American men my age, up for grabs. The war in Vietnam and the Selective Service draft made us eligible to be called up when between the ages of nineteen and twenty-six. For able-bodied suburban men, that meant going to college for the deferment. As the war grew increasingly unpopular, the draft was rightly seen as a class war being waged against the disadvantaged—mostly black or Hispanic or poor who were disproportionately sent into battle. In December 1969, Richard Nixon held the first draft lottery since World War II. The pressing need for more young men as fodder, the gathering storms of protest and public outrage, the inequities of the draft all coalesced into this theatre of the absurd. Three hundred sixty-six blue capsules with the dates of the year were drawn out of a fishbowl in Washington, D.C., on Monday evening, December 1. I was playing gin rummy in the student union of Oakland University. The first date drawn was September 14. Men born on that day were going to war. October 16, my birthday, wasn’t pulled until 254. The first hundred drawn were reckoned to be goners. They’d be suited up and enroute for Southeast Asia before spring of the coming year. The next hundred or so were figured to be relatively safe. The last third drawn were the jackpot winners. They would not be called up for Vietnam. They would not be given guns and sent off to an unwinnable war and told to shoot at strangers who were shooting at them. It was like a sentence commuted. I was free to go.

Up until then, I’d been going nowhere. I was twenty-one, a lackluster student in a state university studying nothing so much as the theory and practice of pursuing women, a variety of card games, the pleasures of poetry and fiction and drink. I had been biding time, doing little of substance, waiting to see what would become of my life. I was living in a sprawling rental house in the country not far from the university with seven other men and the women they could occasionally coax to stay with them. We each paid fifty dollars a month rent and a few bucks for light and heat. The place had five fireplaces, a stream out front, half a mile of woodlands to the main road, acres of scrub grass and ponds out back. We had our privacy. We’d play cards around the clock, listen to the music of the day, drink and drug and arrange great feasts. I was working part-time at my father’s funeral home to pay for the rent and the car and my habits but had steadfastly avoided making career choices yet. It was a life of quiet dissipation from which the number 10-16, the date of my birth, in concert with the number 254, delivered me. It seemed arbitrary, random, surreal. I could do the math—that 1016 was divisible by 254—but couldn’t make out the deeper meaning. As with many of life’s blessings, it was mixed. The certainty that I would not be going to war was attended by the certainty that I would have to do something else. As long as the draft loomed, I could do nothing. But I had escaped it. This was the good news and the bad news.

I considered the options. I had met a woman but was uncommitted. I had a job but no career. I was taking classes but had no focused course of study. I had a future but hadn’t a clue as to what to do with the moment before me.

My closest friend, then as now, was the poet Michael Heffernan, with whom I drank, read poems, and discussed the fierce beauties of women and the manifest genius of the Irish. He had regaled me with talk of his own travels in Ireland and read me what he’d written about the people and the places. At his instruction, I read Joyce and Yeats and Kavanaugh. I switched from vodka to whiskey—it seemed more Irish. I asked my widowed grandmother for an address. She still dutifully sent Christmas and Easter greetings to her dead husband’s distant old-country cousins.

Moveen West Kilkee County Clare Ireland

The syllables—eleven, prime, irregular—then as now belong to this place only: townland, town, county, country, place—a dot on an island in an ocean in a world afloat in the universe of creation to which I was writing a letter. No numbers, no street names, no postal box or code. Just names—people, places, postage—sent. Postmarked all those years ago now: December 10, 1969.

Tommy and Nora Lynch

Moveen West

Kilkee

Co. Clare

Ireland

Like a telescope opening or a lens focusing, each line of this addressing reduces the vastness of space by turns until we get to this place, this house, these people, who are by degrees subtracted from the vastness of humanity by the place they live in and the times they occupy and the names they have.

Since 1970, everything here has changed. Ireland has gone from being the priest-ridden poor cousin of Western Europe to the roaring, secularized Celtic Tiger of the European Union. For the first time in modern history, people are trying to get into rather than out of Ireland, and a country of emigrants has become a nation of commuters. Once isolated as an island nation at the edge of the Old World, the Irish are wired and connected and engaged with the world in ways they never would have imagined even a decade ago. There are more cars, more drugs, more TVs and muggings, more computers and murders, more of everything and less time in the day. Ireland has come, all swagger and braggadocio, into its own as a modern nation. Its poets and rock stars and fiddlers and dancers travel the wide world as citizens of the globe and unmistakably Irish.

Still, looking out the window my ancestors looked out of, west by southwest, over the ditch bank, past Sean Maloney’s derelict farm, upland to Newtown and Knocknagaroon, tracing the slope of the hill to the sea at Goleen and out to the river mouth beyond Rehy Hill, I think nothing in the world has changed at all. The same fields, the same families, the same weather and worries, the same cliffs and ditches define Moveen as defined Moveen a hundred years ago, and a hundred years before a hundred years ago. Haymaking has given way to silage, ass and cart to tractor and backhoe, bush telegraph to telecom and cell phones. But the darkness is as dense at night, the wind as fierce, the firmament as bright, the bright day every bit as welcome.

Everything is the same, but different.

Everything including me. In my fifties, I imagine the man in his twenties who never could have imagined me. I consider the changes in this house and its inhabitants—my people, me.

IS IT POSSIBLE to map one’s life and times like a country or topography or geography? To chart one’s age or place or moment? To say: I was young then, or happy, or certain, or alone? In love, afraid, or gone astray? To measure the distances between tributaries, wellsprings, roads and borders? Or draw the lines between connected lives? Can the bigger picture be seen in the small? Can we see the Western World in a western parish? Can we know the species by the specimen? Can we know the many by the few? Can we understand the way we are by looking closely at the way we’ve been? And will the language, if we set ourselves adrift in it, keep us afloat, support the search, the pilgrimage among facts and reveries and remembrances?

Is it possible to understand race and tribe, sect and religion, faith and family, sex and death, love and hate, nation and state, time and space and humankind by examining a townland of the species, a parish of people, a handful of humanity?

It was in Moveen I first got glimpses of recognition, moments of clarity when it all made sense—my mother’s certain faith, my father’s dark humor, the look he’d sometimes get that was so distant, preoccupied, unknowable. And my grandmothers’ love of contentious talk, the two grandfathers’ trouble with drink, the family inheritance of all of that. And the hunger and begrudgments and fierce family love that generation after generation of my people makes manifest. And I got the flickering of insights into our sense of “the other” and ourselves that has informed human relations down through time. Can it be figured out, found out, like pointing to a spot on a peninsula between now-familiar points and saying: It came from there, all of it—who we are, how we came to be this way, why we are the way we are—the same but different as the ones that came before us, and will come after us, and who came from other townlands, peninsulas, islands, nations, times—all of us, the same but different.

Those moments of clarity, flickering wisdoms, were gifts I got from folks who took me in because I had their name and address and could twist relations back to names they knew. When I stood at their gate that gray February morning, going thirty-five years ago, they could have had me in to tea, then sent me on my way. They could have kept me for the night, or weekend, or the week and then kindly suggested I tour the rest of the country. Instead they opened their home and lives to me, for keeps. It changed my life in ways I’m still trying to understand.

Tommy Lynch died in 1971. He was laid out in the room I sleep in now. After his funeral I rented a TV for Nora from Donnelan’s in Kilrush, thinking it would shorten the nights. Because she was an elderly woman living on her own, Nora got the first phone in Moveen in 1982. She added a roomlet out front to house the new fridge and the cooker. She closed in the open hearth for a small and more efficient firebox. In 1982, my friend Dualco De Dona and I ran a water line in from the road, through the thick wall, into a sink that sat on an old clothes press and gave her cold water on demand. “A miracle,” is what she called it, and praised our “composition” of it all. In 1986, she built a room on the back in which went a toilet and a shower and a sink.

Nora died here in 1992 in the bed I sleep in now. She left her home to me.

P. J. Roche pulled up the old flagstones and damp-coursed underneath them, then knocked out an inside wall to enlarge the kitchen, put in storage heaters, a back-boiler, radiators, and new windows. The place is dry and snug and full of appliances. The civilizers of the twentieth century—toilets and tap water, TV and a kind of central heat, the telephone and tractor and motor car—all came to this place in the past thirty years. Still, little in the landscape out of doors has changed. The fields green, the cattle graze on the topography that rises to the sea out one window and leans into the river out another. The peninsula narrows to its western end at Loop Head, where gulls rise in the wind drafts and scream into the sea that every night the sun falls into and on either side of which I keep a home. Folks love and grieve and breed and disappear. Life goes on. We are all blow-ins. We all have our roots. Tides come and go in the estuary where the river’s mouth yawns wide into the ocean—indifferent to the past and to whatever futures this old house might hold.

The plans for the new room include a sliding glass door out to the rear yard where the whitethorn trees my great-great-grandmother Honora planted a century and a half ago still stand. According to their various seasons, they still berry and flower and rattle their prickly branches in the wind. It was her new husband Patrick who brought them home—mere saplings then—from a cattle mart in Kilrush where the old woman who sold them told him it was whitethorn that Christ’s crown was fashioned from.

There’s shelter in them and some privacy for those nights when, here in my fifties after too much tea, rather than the comforts of modern plumbing, I choose the liberties of the yard, the vast and impenetrable blackness of the sky, the pounding of the ocean that surround the dark and put me in mind of my first time here.

Those rare and excellent moments in my half-life since, when the clear eyes of ancients or lovers or babies have made me momentarily certain that this life is a gift, whether randomly given or by design; those times when I was filled with thanksgiving for the day that was in it, the minute only, for every tiny incarnate thing in creation—I’ve measured such moments against that first night in Moveen where staring into the firmament, pissing among the whitethorn trees, I had the first inkling that I was at once one and only and one of a kind, apart from my people yet among them still, the same as every other human being, but different; my own history afloat on all history, my name and the names of my kinsmen repeating themselves down generations, time bearing us all effortlessly, like the sea with its moon-driven, undulant possibilities: we Irish, we Americans, the faithfully departed, the stargazers at the sea’s edge of every island of every hemisphere of every planet, all of us the same but different.