Inheritance

A Correspondence with Sile de Valera

Ms. Sile de Valera, T.D.

Minister for Arts, Heritage, Gaeltacht and the Islands

Department of Arts, Heritage, Gaeltacht and the Islands

Dun Aimhirgin

43 Mespil Road

Dublin 4

Ireland

6 September 2001

Dear Minister de Valera:

Am writing at the suggestion of Mr. Geroid Williams of the firm of McMahon and Williams, Solicitors, Kilrush, on behalf of certain constituents of yours, living and dead.

It had been my hope to see you in person, to which end I called at your office in Ennis twice in August and in both instances found it closed for staff holidays. I had been in Dublin in June, a guest of the Dublin Writers’ Festival, and lodged at the Mespil Hotel, near the Ministry offices, but at that time was unaware that I would need your help. Last week I spoke to your office in Dublin and they were kind enough to put me in touch with Owen Lenehan who told me you will be in Ennis, in Chapel Street, on the 8th for a clinic. Alas, I had to return to Michigan at the end of August but will, if you can give me a date certain for an appointment, be on the next plane to Shannon or Dublin.

You and I met once before, at a wake. It was late March of 1992 in Moveen West, near Kilkee. It was my cousin Nora Lynch who had died and in her house that we met and I remember how touched I was that you had taken the time to call. Perhaps public servants in Clare, like politicos here in Michigan, find funerals fertile ground for politicking. But Nora Lynch was an elderly woman who had never married and had lived on her own for over twenty years and had neither children nor money nor influence left after her. So I knew you were there for genuine reasons, to pay respects to a woman of your grandfather’s generation, a woman who was truly one of your people. I know that she often spoke of you, as “a mighty lady entirely, young and able, nobody’s fool, well able for those prime boys above in Dublin, &c.” Your being there to pay your respects to a woman who was, while precious to me, of no particular political estate, was a great consolation.

Indeed Nora Lynch’s only estate was the small cottage we met in, there in Moveen, the haggards and out offices and cow cabins around it, enough money to wake and bury her well, and her belief that the 28 acres behind the house, the first freehold in that townland, worked by her grandfather and her father and her brother and that she had worked her entire life were hers to leave to whomever she pleased.

It is those few acres, Minister de Valera, about which I write in hopes you can help me to finally execute Nora Lynch’s Last Will.

In May of 1968, Nora Lynch and her brother Tommy, 65 and 67 years old respectively, having spent years together working the farm, contacted Thomas Stapleton, an estate agent in Kilkee, with the intention of selling their land at public auction and going into retirement.

Tommy and Nora were the youngest son and daughter of Sinon Lynch and Mary Cunningham. While two older sisters and an older brother immigrated to America, Nora and Tommy stayed home, as was the custom, to tend to their ageing parents and the land. Neither ever married. Neither ever moved. Sinon died in 1926 and his widow, Mary, in 1950. In 1968 Tommy and Nora had thirty acres of grazing and hay and haggards. Nora sowed half an acre of potatoes, half an acre of oats, an eighth of an acre of turnips and a bit of cabbage. They kept, according to the inventory that appears on an Attendance Docket, “six good milch cows, 5 calves, 1 mare pony in foal and 1 ass.” They also had “1 mowing machine, 1 rake, 1 slide and 1 haycar.” The thatched house was three rooms and a kitchen, no plumbing, four lightbulbs and a socket for the radio and one for the kettle and a votive lamp to the Sacred Heart. No doubt you’ve been in hundreds like it.

Tommy rose early every morning to milk cows by hand and ride by ass and cart the eight miles round trip to Doonaha Creamery. Nora kept chickens and a couple geese and tended the haggard. She did the marketing and prepared the meals. They both worked the land long into their age. It was, as you know, subsistence farming, bearing more resemblance in work and routine to three centuries earlier than to three decades since.

It was the 25th of May 1968 that Thomas Stapleton, an auctioneer in Kilkee, wrote to Michael McMahon, a solicitor in Kilrush, to seek clear title to the land (which at the time was still listed to Sinon Lynch) alerting him to Tommy and Nora’s intentions and his plan to “offer the holding by Public Auction at my salesrooms on June 22nd.”

(Mr. Williams has allowed me to copy the entire file on this matter from his office records. Also I have, such as they are, all of Nora Lynch’s papers. So any quotations come from actual documents, copies of which I will, on request, supply.)

Mr. McMahon then wrote to Tommy Lynch on the 31st of May 1968 suggesting they meet in Kilkee “on some evening that is convenient for you” to discuss “some particulars of title.” This they did on the 3rd of June. Everything appeared to be proceeding apace for Tommy and Nora to sell their land, keep their home, and settle into a deserved retirement in the familiar landscape and friendly society of Moveen, living, they most likely hoped, into ripe old ages on their little pensions and equities.

But this never happened.

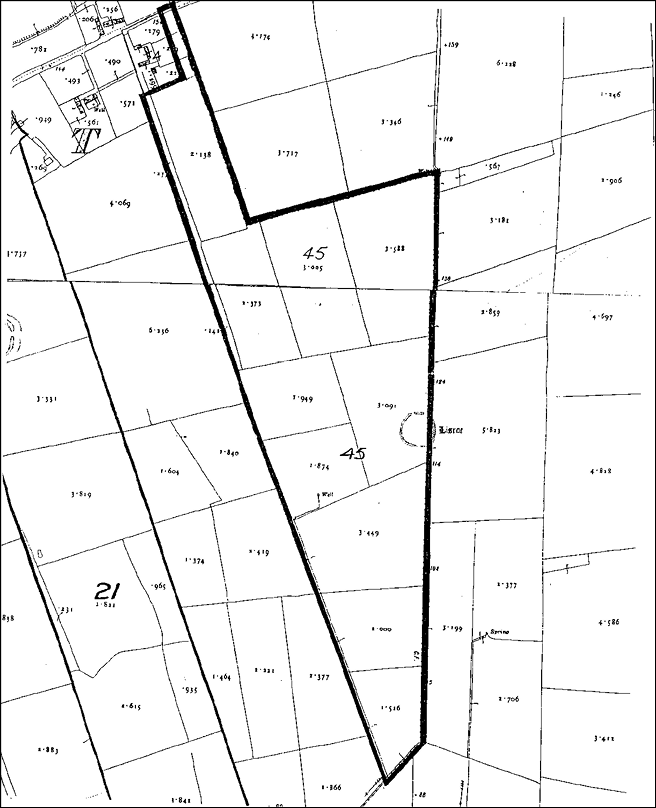

On the 17th of June 1968, a fortnight after Tommy and Nora Lynch met with Solicitor McMahon in Kilkee to discuss the upcoming auction and the necessary updates to the Folio in the Land Registry, a handwritten entry is made in that Folio, #22447, in Dublin, to wit:

“The property is subject to the provisions prohibiting sale, transfers, lettings, sub-lettings or subdivisions without the consent in writing of the Land Commission contained in section 13 of the Land Act.”

With this entry the rights of two honorable, elderly citizens to retain or dispose of the land that had occupied their lives and times and those of their parents and their parents’ parents were lost.

The entry was made by a nameless Dublin clerk at the instruction, no doubt, of somebody who knew somebody who knew somebody who knew somebody else who, for reasons we might never know, had an agenda at odds with Tommy and Nora Lynch’s.

They had committed no crime, done no dishonest thing, left no rate or rent unpaid. They had simply endeavored to sell their property by public auction or private treaty to whomever was willing to pay a fair price. And yet their right to do so was summarily removed by an entry in a ledger book by a Dublin bureaucrat.

You were, of course, a schoolgirl then, and I was not yet twenty. It was a tree, to paraphrase that Dublin churchman, that fell in the forest quietly. But fall it did.

On the 23rd of August 1968, Tommy and Nora were notified that the Land Commission had inspected their lands and had “decided to proceed with the acquisition of these lands in accordance with the Land Purchase Acts and the prescribed notices [would] be published and served on you in due course.”

How the Land Commission came to be involved is anyone’s guess. How does an agency in Upper Merrion Street in Dublin 2 get wind of private dealings in West Clare? I know that neither Tommy nor Nora contacted them. And I suspect that the estate agent, Mr. Stapleton, didn’t either, for surely he looked forward to the commission he expected on the auction of these lands, which he had by then advertised in the Clare Champion. Would Mr. McMahon have any reason to notify them? Was he required by any law or protocol to do so? Had he other clients in Moveen? Did he stand to gain anything by preventing a private sale or by protracting these dealings? Who is to know? I never met the man. Mr. Williams assures me his late partner was “punctilious” in every matter. Years since his death his reputation for ethical and honest dealings remains intact. So was it a neighbor who read Mr. Stapleton’s notice in the Champion and knew someone who knew someone &c.? Indeed, who is to know? But there it is.

Nora always said it was a consortium of neighbors who had “put in for it.” She called them “grabbers” and said “they wanted to get it for nothing.” And I know who she said those neighbors were. And I know why.

In any case, Nora and Tommy filed an Objection to the Land Commission’s action and in June 1969 a hearing was held at the courthouse in Ennis at which they represented that there was no reason for the Land Commission to be involved in their property. They were working the farm to its full capacity, the land itself was in good order, rents and rates had always been paid, they’d never let any portion of the lands and they expected that a young relation from America would be coming to take it over for them. This last particular Nora made up. I think she was playing for time, hoping that the Land Commission’s interest would disappear as quickly as it had appeared. Indeed, “after hearing the evidence of the Objectors, the Commissioners adjourned their further consideration of the objection for a period of two years.”

No doubt Nora counted it a little victory. They wouldn’t be able to retire but they wouldn’t give into the “grabbers” or sell it for “worthless bonds.” They filled their hay barn that summer, had their cows inseminated and hunkered down for the winter surrounded by neighbors with whom their relationship was now suspect.

This is where I came in.

In December of 1969 I was 21. I was a lackluster university student, doing English Literature and Psychology here in Michigan, trying mostly to avoid the draft and any life-changing decisions. My only attachments were to the work of Yeats and Kavanaugh and the new Irish poet Seamus Heaney and to the fiction of Joyce and John B. Keane and Flann O’Brien. My favorite American poets, John Berryman and Theodore Roethke, had both been to Ireland.

And I knew we had some family connections there. I suppose, like Nora, I was playing for time. I was in no hurry to begin a career or family or life’s work. I believe she believed it was an Act of God by which the necessary fiction she’d told the Land Commission the summer before about “a young relation from America” became fact in the hapless person of myself, landed in the road at their gate in February 1970. In due course I was given the tour of the “first field” and the “far field” and the “fort field” and the “big meadow” and the spring well of “sweet water” that rose in the land; and told what a good living a man like me might get from land like this and how any woman would be happy to marry into such a place and after all it was my great-grandfather, Tom Lynch, who had left and only right that I returned.

It was clear Nora had a plan for my life. I told her I wasn’t a farmer but that I thought it very generous of her to offer all the same. I knew nothing, of course, about her predicament with the Land Commission.

In the weeks that followed, I was taught to milk cows and to help with their calving, to clean the cow cabins and keep the fire, to cut hay from the hay barn and bring it to cows, and to make my way through the muddy fields for buckets of drinking water for the house. At Brew’s in Kilrush, Nora bought me a pair of Wellingtons. I’d ride the bike alongside Tommy, on his donkey cart, to the creamery and out with Nora to visit neighbors.

Tommy taught me the management of dung and manure, the habits of cattle, fishing the cliffs for mackerel and twisting relations by the fire with Nora. I returned to America in early May, worked for three months, and was back in Moveen in August to draw turf with Tommy from the bog in Lisheen and enjoy the high season in Kilkee—open-air ceili dancing in the square, pony races on the strand, sing songs in the pubs.

And when neighbors would ask, “How long are you home for?” I’d tell them matter-of-factly, “not long enough.” Nora would always insist that I “not present our business to any one of them. Tell them you might stay on altogether.” I knew then there was subtext to her concerns. One night she told me about the Land Commission.

On the 9th of March 1971, Tommy Lynch died in his bed without medical attention of what was, I daresay, a treatable pneumonia. He was 70 years old and had been trying to work the farm like a younger man, to keep the Land Commission from taking it from him. His heart gave out. “A glass of water and a heave and he was gone, the poor cratur,” is how Nora told it to those who asked. Nora biked into town to the Post Office and phoned me in Michigan. I flew over that night and was there for the wake and removal to Carrigaholt and the Mass and burial the following day.

It took a month to sell the stock and the hay barn and to get the roof slated and to go to Dublin for her passport. It was the first time she’d been in her nation’s capital. And the first time she’d ever been on a plane. I brought her to America where she stayed with my family for a few weeks and then she rode out with my grandmother to Buffalo, New York, to see the two sisters she hadn’t seen in over fifty years.

I don’t know what happened there. My guess is it didn’t go very well. It is the scourge of emigration—the guilt and shame on either side. Maybe their welcome was not warm enough. Maybe she was hoping they’d ask her to stay. Maybe there was old business never finished. Whatever it was, she called the visit “a dead loss” and flew home to West Clare the following day, determined to fight the Land Commission’s efforts to take her land. She was frightened and alone, grieving and powerless and surrounded by neighbors she felt betrayed by. She was 68 years old and on her own.

That summer of 1971 whilst the appeal was pending, the Land Commission excluded the “dwelling-house and an accommodation plot” from “their proceedings,” thereby giving Nora Lynch title to the roof over her head and the rooms she had lived in all of her life and the haggard and yards. They were apparently prepared to evict her from her own lands but not from her own bed.

At a hearing in Ennis that October her former objections were denied. Her brother was dead, the cattle were sold, the land was not being worked to its potential, the Land Commission’s right to take up her land and re-distribute it among her neighbors was affirmed. So Nora began to quibble about the price and the method of payment. Again, it would seem, she was playing for time.

They’d offer one sum, she’d counter another. They’d offer land bonds, she’d insist on cash.

“I could be in America since my brother died,” she wrote, “if they let me sell my land. I had plenty of buyers. We offered the land for full market value in cash as I am living alone and my friends are all in America and I have no one to fight for me. I have got my land valued and you know the value of land now. I’ll have to get paid in cash and that’s definite.”

Nora was able to get the County Council to appeal the Land Commission’s action on her behalf “upon the grounds that the price so fixed by the Irish Land Commission is inadequate and does not represent the true value of said lands.”

In August of 1972 I returned to Ireland to see if Nora was making any progress. She was frightened and beside herself, bitter that a conspiracy of neighbors, through the Land Commission, was preventing her from a private sale of her land. She wondered if she should give up and join a convent but she felt it was her duty to fight for her rights in the matter.

In the space of four months, qualified buyers made no fewer than four offers to Nora Lynch for the private sale of her land. In each case the Land Commission refused to allow the sale, though any one of them would have accomplished the stated goals of the Land Commission to consolidate smaller farms with larger adjacent ones so that they could be worked more efficiently. One can only assume that the Land Commission had another quite separate agenda with regards to this land.

Of course, all that follows from the Land Commission is enquiries as to “when possession can be obtained.” For them, it is a closed matter. The price has been set at 4250 Punts.

On June 22, 1973, Iris Oifigiuil listed the 28 acres in question in its Final List.

The Land Commission sent notice in June that they would acquire the lands on the 17th of August 1973. But when they appeared at the gate Nora Lynch refused them entry. They could not gain possession of the land.

There’s no telling why everyone seemed to back away from further confrontation at this point. Perhaps it was the look in Nora’s eye when the Land Commission’s agent appeared at her gate. Perhaps there was a change of policy in Dublin. Perhaps the people pressing for the acquisition decided that it would be easier to wait it out. Nora’s brother had died in the midst of this imbroglio. She was getting older and had been under a lot of stress. And while I had been in Moveen frequently in 1970 and 1971 and 1972, marriage and career and family obligations meant I couldn’t travel there in 1973. I did send for Nora and she made a brief visit to America in 1973. Still, maybe my absence was taken as a signal to them. Perhaps the consensus was that soon enough Nora would die and I would disappear and then they could acquire the lands without having to further pester an old woman. I do not know. But I know that Nora believed that the Land Commission had withdrawn from the matter because they wouldn’t pay her cash.

And I know that six years later, when I made my first trip back to Moveen in September of 1979, for whatever reason the case was suddenly reopened again. Two weeks after I left, a letter to Mr. McMahon from the Land Commission made known their intention to seek an Order of Possession. “Please let me hear from you without delay,” it concluded.

At the suggestion of a friend, the late Paddy Murphy of Ballina, Co. Mayo, I contacted the Solicitor Adrian Burke. Paddy told me Mr. Burke was a friend and a fine attorney and that his sister, Mary Robinson, was a Senator and they were well connected.

Mr. Burke was representing a family in a legal case against the Land Commission for unfair acquisition of their lands. It was very similar to Nora Lynch’s case. He told me that the case would work its way through the lower courts and eventually to the Supreme Court and that most likely, regardless of the outcome, there would be Appeals and that the whole process would take several years. For a small fee he agreed to attach our case to this other case. I sent him a check. He advised that Nora Lynch keep possession of her lands and under no circumstances give it up or take payment for it. I asked him about the wisdom of allowing a neighbor’s cattle in the land and he said to go ahead, that it would prove the land was being used.

I confess at this point I was playing for time. I wanted Nora Lynch to live out her life in possession of her lands. She was 77 years old, still living without transport or plumbing or central heat, in a damp climate in a damp cottage near the sea. She had refused our invitations to live in America. She had abandoned her plan to move into a convent. She wanted to live in her own house on her own lands and to exercise her rights as a hardworking, honest woman.

It was also plain why neighbors would want to get the land. All through the 1970s, emigration was the scourge it had always been, tearing families apart, banishing the young to England and America. As a parent, I could certainly appreciate a farmer’s desire to expand the family holdings to keep as many of the children in the land as possible.

So I believed that if Adrian Burke’s case could outlive Nora Lynch, everything might work out in the end. In fact, Mr. Burke was as good as his word. We never heard another word from the Land Commission. Nor did they ever attempt again to gain possession of Nora’s land.

Nora came to Michigan for a visit in the summer of 1980. She seemed more relaxed. But still, after a month she began to worry that the Land Commission would take her lands in her absence. Every day her fear of this worsened. She cut short her visit and hurried back to Moveen.

Through the early 1980s Nora Lynch rented her land to various farmers for silage and pasturage. Relations with the neighbors, though occasionally tense, seemed to normalize. Whether it was local politics, Adrian Burke, or the Will of God, the Land Commission did not seem a present threat.

In 1985 she let the land to P. J. Roche, a young man from a townland between Cross and Kilbaha, who had recently married a woman from Ennistymon. He wanted to farm. He had a few acres just south of her land where he lived in a mobile home with his wife. Nora’s letters were full of praise for this man. I believe P. J. reminded Nora of her brother Tommy. He rose early, worked late, tended his cows and improved the land. What is more, he would call into Nora mornings and evenings when he came by to check the cattle. And his wife Breda called in whenever she was going to town to see if Nora needed anything. At the birth of their daughter, Louise, they moved into their home in Newtown, at the edge of the ocean, from whence they could see Nora’s lights and she could see theirs. When a cow was calving, she’d summon him at all hours, throw on the yard lights and make the tea. They’d talk farming and the price of things and the vagaries of the weather.

In 1988, after the publication of my first book of poems, I was given a fellowship to the Tyrone Guthrie Centre at Annaghmakerrig in Newbliss, Co. Monaghan. I cut short my residency there to go down to Moveen and visit Nora. She was nearly 86 years old but she was happier than she’d been in the long years since her brother had died. With P. J. and Breda Roche around, she didn’t feel alone. There were still some tensions with some of the neighbors, but with the Roches’ cattle in her fields, wintering out in her cow cabins, the fields being properly maintained and P. J. and Breda coming around with their infant daughter Louise, Nora Lynch felt once again engaged in the familiar life of her townland.

For me it was a great relief, having spent the most of twenty years concerned that Nora might fall ill or fall down or die alone and unhappy and under siege from forces over which she had no control; it was a great comfort to see that P. J. and Breda Roche treated Nora Lynch like family. She could not have lived on her own into her age without the daily kindnesses this young couple extended to her. Once, over pints in Carrigaholt, P. J. Roche made known to me his hope that if “God forbid anything should happen to Nora,” he’d like me to know he’d like to buy the land from me. I told him I couldn’t predict the future but “take care of Nora and I’ll take care of you.” In fact, Nora had made inquiries herself, with Geroid Williams, who had by now succeeded the late Michael McMahon as solicitor, to see if she could sell the land to Mr. Roche. He counseled against it. His advice was to leave well enough alone. The Land Commission had backed off their efforts to gain possession of Nora’s land though they had in fact, for fifteen years, been recorded as the owners of it—a fact Nora Lynch never recognized. In her mind they hadn’t any right to it, hadn’t paid her a thing and she never allowed them inside the gate.

In 1988, Nora Lynch dictated to me her first Last Will.

It appointed me as the executor and charged me with the “distribution of her estate.” It read in part:

Firstly it is my wish that the land that I and my late brother, Tommy Lynch, owned and worked all our lives be purchased at fair price and worked by Mr. Patrick J. Roche of Newtown. I have wanted to consummate the sale of said lands with Mr. Roche but am prevented by the Land Commission. I understand that as of August 1973, the land has been vested in the Irish Land Commission. However, I have never accepted payment of any kind from the Land Commission nor have I allowed them to take possession of the land since I believe they have no right to do so. Accordingly, I have rented the land to Mr. Patrick J. Roche since 1985 and he has taken good care of it. In the event of my death, should our dealings with the Land Commission not be finished, I instruct them to vest the land in Mr. Patrick J. Roche of Newtown. He has proved himself to be an honest, hard-working family man and has been kind to me in my latter years.

She left her home and haggards to me. As this was the home our common man, Pat Lynch—her grandfather and my great-great-grandfather—had been given as a wedding gift, and the home my great-grandfather left in 1890 to come to America, it was and remains a precious inheritance to me.

Thanks to P. J. and Breda Roche, Nora lived out her last years a happy woman, vexed by the unfinished business of her land, but secure in the knowledge she had fought the good fight and stood her ground against the “grabbers” and “blackguards,” whoever they were. She had taken no money, lived on her pension and foregone the comforts of retirement for the sake of principles.

In November of 1991 Nora was hospitalized briefly with what the doctors in Ennis called “gall stones.” It was, we would figure out later, a cancer. I was in England on literary duties when Breda called my wife, Mary, in Michigan.

In February of 1992, Breda called with the news that Nora had fallen in her kitchen and was taken to the county hospital in Ennis and that the prognosis was very poor. I flew over to sort out what I could. With P. J. and Breda’s help, we got her home where she was happiest.

Still Nora was worried about what would happen after her death. She asked me to go to Dublin and settle the business with the Land Commission. Through my friends, the poets Eilean Ni Chuilleanain and Macdara Woods, I’d met Paddy McEntee, the Senior Counsel, some years before. It was through his office I was directed to see Mr. Cathal Young in Lower Leeson Street to discuss what might be done with the Land Commission. I met with him on the 9th of March in 1992. Mr. Young thought Mr. Roche’s chances to purchase the land from the estate—especially one executed by an American—were very poor. The Land Commission, though they had long since stopped acquiring properties and had begun in 1989 to sell off their land bank, still had vested themselves as owners of the lands in the Folio, leaving Nora Lynch a squatter on her own land.

I returned to Moveen with the matter still unresolved and gave the news to the dying woman. I suggested that she rewrite the Will and leave the land in question directly to the Roches, not for sale, but as inheritance. It seemed to me the correct thing to do. Their kindness and companionship had made it possible for her to live her life out in her own home, in charge of her own affairs, dependent on no one. If, indeed, the fight for that land must carry on, it seemed to me the case would be strengthened if a young Irish farmer were fighting for an inheritance of land he had worked in and had left to him by a woman who had worked it, rather than by a middle-ageing American poet. This made sense to Nora too.

On the 10th of March 1992, Geroid Williams came to Nora in Moveen and prepared her new Last Will and Testament. It appointed me sole executor, directed me to pay the customary debts and expenses and reads, in part:

I do not accept that the Land Commission has any right to my lands at Moveen East and West. I have been in possession of these lands all my life. Patrick J. Roche is at present tenant of these lands and has been very good to me. I give devise and bequeath all my lands at Moveen East and West to the said Patrick J. Roche and Breda Roche both of Newtown, Carrigaholt.

I give devise and bequeath my dwelling house, haggards, out-offices and cabins registered in my name at Moveen West to my cousin the said Thomas Lynch absolutely.

Nora died on the 27th of March in her own bed, in the room she was born in nearly ninety years before, and was waked there for three nights, it being wintry, and buried in the vault in Moyarta among the bones of her people and mine. Her obsequies, indeed the last weeks of her life, were well attended by her neighbors, all old grievances having been put aside in the name of still older friendships and common struggles.

I’ve kept the house and, with P. J.’s help, made it more habitable and able to withstand long absences. It has become a kind of retreat for writers. Irish and English and Scots and Dutch, Australian and American and one New Zealander—poets and novelists and journalists—dozens of them have benefited from the quiet and dark there and the friendly ghosts. A. L. Kennedy wrote On Bullfighting there. Mike McCormack did parts of Crowe’s Requiem. Philip Casey wrote some of The Water Star. Mary O’Malley and Jessie Lendennie, Macdara Woods and Eilean Ni Chuilleanain, Robin Robertson, and Matthew Sweeney have all written poems there. Even the Heaneys had lobster there one summer evening a couple years ago. I think that Nora would approve. She regarded writing as an honorable trade, not unlike farming—“the poetry business,” she always called it. I am there two or three times each year, whenever I’ve a good excuse. And my large extended family has restored its roots in West Clare for another generation. All to the good.

Still one bit of Nora’s business remains unfinished.

It is going ten years since Nora Lynch died in Moveen. She never lived to hear the Celtic Tiger roar or see real signs of hope in The North, or watch the young come and go as they please around the country and among the countries of the world. Cell phones and central heat and holiday homes proliferate. It is another Ireland entirely from the one she knew. Nor did she ever have the certain knowledge that her lands would go to the ones she willed them to.

In West Clare now the question is not whether there’ll be sufficient land for farmers but whether there’ll be sufficient farmers for the land. The young will not be “grounded” in the way their parents were. They travel light now, like other Europeans through open borders, common markets, and virtual realities. No longer emigrants, they are ambassadors of Irish culture and competence.

P. J. Roche still works the land as he has for over sixteen years now. Like many Irish farmers he also works construction to make ends meet. He keeps his cattle and his horses. He does masonry and plastering. His daughter Louise is in her teens. Breda works weekdays in the local shops. It is a good life and he is grateful for its blessings.

But he cannot stand in the land and call it his. Nor can he make the necessary improvements without clear title. The grants from the Rural Environmental Protection Scheme for the construction of a slatted house for his cattle are not available to him because he cannot produce proof of ownership. Nor will any lender loan him money against land that he works and occupies but does not own. Without clear title P. J. Roche is, as Nora was, a squatter on land he has long labored in. His work has not purchased any equity for himself, his wife or his daughter.

This is wrong.

It is a profound and longstanding injustice that quickened Tommy Lynch’s death, cast a pall over Nora Lynch’s life and severely limits P. J. Roche’s future. Since 1968 the actions of the Land Commission have dishonored the honest labor of honorable people, made meddlers and quarrelers of good neighbors and served no defensible purpose for the State. It is long overdue to right this wrong.

For years, Mr. Williams has advised us to wait out the statute of limitations—thirty years. He has advised for years that the thirty years was up this year: thirty years since the land first appeared on the provisional list. But now he says, maybe thirty years since it appeared on the final list—2003! I ask why not thirty years since the Land Commission first made known their intentions, thus 1998? Or what if it is thirty years since they last sought an Order of Possession, which would bring it to 2010? Who’s to know? Haven’t we waited long enough to answer the simple questions?

Has not an Irish citizen and freeholder of land the right to dispose of that land in any reasonable way she sees fit? Or has the State the right to make her, for no apparent reason or compelling need, forfeit her title and rights in the matter?

Does an elderly, unmarried woman have fewer rights and protections than the young, the married or the male?

What other farms were seized in Moveen by government fiat? Was this case the exception or the rule?

Is it justice or politics that ought to determine these cases? Does cronyism trump honest labor and property rights?

Is there any legal, political, social or moral purpose to be served by letting the Land Commission’s misadventures stand rather than giving title to Mr. Roche in accordance with Nora Lynch’s wishes?

Which is why I write now, to beg for your intervention and good counsel, as my penultimate resort. My obligations to the estate of Nora Lynch and to her memory will not be met until this matter is settled.

Changing the world seems an impossible task. But changing twenty-eight acres is a start. The damage was done by the stroke of a pen, in a Folio in Dublin thirty-three years ago. Oughtn’t it be undone just as easily? It is my hope you will help us do it. If so I will keep a record of it. If not, I’ll keep the record of that too. I am a writer. It is what writers do.

Every goodwill,

Thomas Lynch

Moveen West, Kilkee

Milford, MI USA

In January a letter arrived, on government stationery with the colored logos of the Ministry and the Dail:

Dear Mr. Lynch

Following my ongoing representations to my colleague, Mr. Joe Walsh, T.D., Minister for Agriculture, Food & Rural Development, concerning the procurement of title to the lands at Moveen West, Kilkee, Co. Clare, I am pleased to enclose the Minister’s latest correspondence in this regard.

I understand that on being asked to clarify the attached letter, the Department of Agriculture stated that title will revert to Nora Lynch and that a solicitor acting for P. J. and Breda Roche will then need to rectify title.

Unfortunately, the Department of Agriculture could not give a timeframe as they have just begun the first case of this nature. They did, however, state that the “Lynch case” will be dealt with next and that they will then be in contact.

I hope you are pleased with the above news and if I can be of any further assistance in the future, please do not hesitate to contact me.

Kind regards,

Yours sincerely,

‘Sile’

Sile de Valera, T.D.

Minister for Arts, Heritage, Gaeltacht and the Islands

Settlement of “the Lynch case” came in February 2002 from the Department of Agriculture:

Dear Mr. Lynch:

The Land Commission have submitted an application to us here stating while they became registered owners in 1973 of part of Folio CE22447, now CE999F (copy enclosed) they never took possession of the property. The lands remain in the possession of the previous registered owners. Sinon Lynch is full owner of property nos 1 and 2. Thomas Lynch and Nora Lynch are the owners of property 3.

We propose to reinstate Sinon Lynch as full owner of Property Nos 1 and 2 and Thomas Lynch and Nora Lynch as full owners of Property No 3.

We note on foot of your application in 1992, you became sole owner of the residue of Folio CE22447.

You may wish to lodge an application to become the registered owner of Folio CE999F if you are entitled.

We will proceed to register as stated above within 21 days.

Yours faithfully,

Daire Guidera

May 21, 2003

Dear Minister de Valera:

The last letter I wrote you was longish indeed, detailing the history of Nora Lynch’s land and my interests in it. This will be briefer. Is it not always so—that please is always windier than thanks? Still these are thanks, underwritten and overdue, for your intercession on our behalf.

The slatted house that P. J. Roche has finished this year stands on his own ground. The greening of it, the grazing of it, the pride in it and profit of it all are his. His wife and his daughter are the more secure. The future is theirs to make of it what they can.

What is more, your representations on behalf of the estate of Nora Lynch, long deceased, restore a proper title to the past. The land was hers to give. And though it took ten years to make the gift complete, it is done now and there is justice in it.

Here in Michigan, the world and its wars and my own duties have kept me from travel to Ireland this spring. But my middle son, Michael, was over in February, taking advantage of the off-season, post 9-11 fares. He reported that February this year was much the same as I remember February there decades ago. The thought of him sitting in Nora Lynch’s house, four generations removed from the young man who left there in 1890 and who started our family in America, fills me with a sense of the grandeur of Time.

You’ve used your time well, Ms. de Valera. Your grandfather would be proud of you. And my people are grateful to you always.

I’ll be in West Clare, please God, the months of August and September and will call to your office in Ennis in due course to tender thanks in person. Or if you’re out Moveen way, please pay a visit. You’ll see what goodness your work has wrought.

All the best,

Thomas Lynch

Milford, Michigan & Moveen