On Some Verses by Irish & Other Poets

I was in the “Deux Magots” in Paris one time and an American that I was introduced to asked me if I had known James Joyce. I said that I hadn’t that honour, but I told him my mother had often served a meal to W. B. Yeats in Maud Gonne’s house on Stephen’s Green, and that the poet turned up his nose to the parsnips. “He didn’t like parsnips?” said the American reaching for his notebook. “You’re sure that is factual?”

“It is to be hoped,” I replied, “that you’ve not called my mother a liar?”

“No, no, of course not,” he said, “but she might have been mistaken—it might have been carrots,” he added hastily.

“You must think I’m a right fool to have a mother that can’t tell a carrot from a parsnip,” I said nastily.

“No, no, of course—I mean I’m sure she could but it is very important. . . .” He wrote in the book: Parsnip—attitude of Yeats to.

—Brendan Behan, in Brendan Behan’s

Island: An Irish Sketchbook

I’VE THIS IMAGE of the poet hammering lobster on the flagstone floor.

They’ve been to the fishmonger’s in Carrigaholt, bargained for a pair of behemoths, brought them back to Moveen to be boiled and now, bottles uncorked, spuds ready, butter drawn, the small room blurry with steam and hunger, they find that they’ve no utensil sufficient to liberate the sweet meat from its hard shell casing. Thus the hammer, the “flaggy floor,” and the “sense of a feast that had been fought for,” the poet sends word in a note: “Great debris and great delight.”

It’s all metaphor—the lobster, the hammer, the flagstones, the feast—one meaning carried by another, as if “to bridge” (if we trace the word back to its Greek) the gap between what is and what really is.

I stole that thing about the bridge from another poet, who read it somewhere or stole it from another one or made it up. It’s what we do: rent to own, borrow, steal—make things up and metaphor. Sometimes nouns are transformed into verbs. You may try this at home.

Poets can’t help themselves. Every one of them—stone mad for double meanings, second helpings, things that are more than they seem. Or less. “All the world’s a stage,” writes Shakespeare. We bow to the audience that isn’t there. Adjust our costume. Memorize our lines. Imagine “all the world’s” watching, waiting, listening. They never show.

IT WAS A poet who told me to go to Ireland. And poems that first made me want to go. And poetry that keeps the lights on now, in the house that Nora Lynch bequeathed to me.

The first living poet of my acquaintance was teaching at Oakland University in Rochester, Michigan, in the fall of 1967. I took Professor Michael Heffernan’s class in American Authors—Emerson, Melville, Thoreau, and Poe. Because he was young and apostate, Irish and American, a variously lapsed and observant Catholic, we became fast friends and drinking buddies. At his rented house on Brown Road, fifteen minutes from the campus, we studied Yeats and a variety of domestic and imported whiskeys and the Boston Symphony under Charles Munch. In this house I heard my first Mahler, drank my first Irish, and saw for the first time poems in the making. Each left me breathless and wanting more.

KENNEDY

One late afternoon I hitched from Galway down to Kinvara on the

edge of the Burren, one of those long midsummer days when

the sun labors at last out of all-day rain and sets very late in the

evening. In dark pubs all up and down the street, the townsmen

hunched to their pints, silent and tentative as monks at supper.

Thinking to take my daily Guinness, I stopped, and Kennedy

was there, his picture on the mantel behind the bar.

A black-headed citizen half in his cups sidled over and smiled. Ah

Kennedy Kennedy, a lovely man, he said and bought me a Guinness.

Ah yes, a lovely man, I said, and thank you very much. Yes

Kennedy, and they slaughtered him in his youth the filthy com-

munists, he said, and will you want another. Yes, slaughtered him

in his youth, I said and thanked him very much.

All night till closing time we drank to Kennedy and cursed the

communists—all night, pint after pint of sour black lovely stout.

And when it came Time, I and my skin and the soul inside my

skin, all sour and lovely, strode where the sun still washed the

evening, and the fields lay roundabout, and Kinvara slept in the

sunlight, and Holy Ireland, all all asleep, while the grand brave

light of day held darkness back like the whole Atlantic.

Heffernan’s “Kennedy,” drafted, corrected, revised, and retyped over the space of several months that autumn and winter, was elegant to me, bearing as it did the beauty of homemade words on the page. He called it a prose-poem and said he had an interest in the form. The idea that any day in any bar anywhere in Ireland could produce such a text produced in me the grand illusion that any parish in Holy Ireland was more inspiring than any place in suburban Michigan. Old monkish men, the ocean and light, Kinvara and Galway, talk of Kennedy and sour, black, lovely stout all seemed impossibly distant to me, and wonderful.

And poetry. The idea that an ordinary life in southern Michigan could produce a share of extraordinary words I owe to Michael Heffernan, because he was the first I’d ever seen—the first living poet with a Buick and a business suit and designs on a life that included an eventual marriage, a mortgage, and a full-time job, instead of the apparently requisite style of poets then—driving off into the late-sixties sunset in a rusted VW bus in bell-bottomed jeans, old sandals, and more hair than I would ever have. Here were poems that stung the heart about wanting women and the way that light shone on things, figures of plain force, myth, and history—and I knew that Ireland figured into it. What was more, though the moment that produced “Kennedy” could be traced to a bar in a small town in the golden, open West of Ireland, the work that produced it had been done in a bungalow on Brown Road near Pontiac, Michigan, in the shadow of auto factories and the interstate. One could come and go, traveling light in the portable universe of words, counting on images for transport.

In the course of the next couple of years, I introduced Heffernan to his first wife. He introduced me to Roethke, Berryman, Frost, and Bishop. He and his missus moved off to southeastern Kansas with a U-Haul to live in a big house and teach in a small college. He started publishing his poems in the quarterlies and journals. She grew more and more discontent. In February of 1970, I left for Ireland.

The book I took with me was The Collected Poems of W. B. Yeats. It was a hardbound blue book with the author’s monogram embossed in gold on the front cover. I had a few of the poems or portions of them off by heart.

When you are old and gray and full of sleep

And nodding by the fire, take down this book

This seemed so excellent to me, warming my shins to the sods in Moveen that first winter I spent there decades ago. And Tommy Lynch, my cousin and namesake, his Wellingtons still wet from mucking about after milking his cows for the evening, would sit there at seventy, smoking his Woodbines, listening to my recitations.

“By cripes that man’s a great one for the words—that William Butler Yeats, sure faith he is.” And when I’d pass the book to him, he’d read it out with the precision he’d learned from the Moveen National School on the Carrigaholt road when he was a boy.

“Now for you, Tommy!” Nora would say, busy with the evening’s tea. “You’ll have it by heart like a shot! Sure faith.”

We were an odd trio—the old bachelor, his spinster sister, the blow-in Yank with his poetry and pocket watch—the room full of longings and imaginings, futures and pasts, the godawful winter lashing out of doors.

The notion that a book, a book of poems, could speak to one’s beloved in her age, and say things that the poet meant to say but never could; and maybe quicken in her the caught breath, the look, “the soft look,” Yeats called it, “your eyes had once, and of their shadows deep”—this had a powerful appeal to Tommy and to Nora and to me. It was, in my twenties, the sure faith that time, distance, and life’s imbroglios could not trump love. Most days in my fifties I still believe it and I believe that in their seventies Tommy and Nora did too.

Beyond all of which there was the sound—the iambics and the rhymes—the acoustic infrastructure that made the saying of it such a pleasure. The ten-syllable line with its five thumps—this pentameter—echoed my own internal meter. I could walk its walk and talk its talk—daDum, daDum, daDum, daDum, daDum: when You are Old and Gray and Full of Sleep.

Of course, I made the requisite Yeatsian pilgrimage, hitching to Kilrush and Ennis, thence north to Gort, then on to Coole Park to see the swans and the tree with the great man’s initials in it and on to Ballylee where the ancient tower stands, albeit not in the ruins he predicted, with its bridge and river, the broad green pasture, the hum of the motorway out of earshot, jackdaws diving from tree to tree. And carved on a stone there by his instructions, the inventory of “old mill boards and sea green slates/and smithy work from the Gort forge,” with which he had “restored this tower for my wife George”—the briefer line, the solid rhymes, the declarative confidence, like the music country people danced to. Lucky enough, I thought, to marry a woman named George—if only to rhyme her eventually with “Gort forge.”

I slept in Galway that night. Then on to Sligo, where, following the poet’s instructions, under bare Ben Bulben’s head, I found Drumcliff churchyard and the grave upon which I cast as cold an eye as I could muster, said my thanks, and went away. I walked around the Lake Isle of Innisfree, located the waterfall at Glencar and the rock at Dooney where the fiddler played.

I was young. Poets were my heroes. Where they’d been is where I wanted most to be.

So I wandered around Ireland as long as I could, night-portering in Killarney, learning to milk cows and manage dung in Moveen, reading Yeats and dreaming of the future, wondering what my true love’s name would turn out to rhyme with.

For most of the next two years, I vacillated among travels in Europe, the job at my father’s funeral home, and an undirected course of study at the university.

In August 1971, I was in Venice with my friend Dualco De Dona, who had moved back to his family home in the Dolomites. We’d done the Grand Tour—Greece and Vienna, London and West Clare—back and forth and ended up at breakfast on the Grand Canal, in the salon of the Hotel San Cassiano, variously aching, as the young do, for art and love, some direction to life, and a future that included poetry.

Restless, broke, and mildly hungover, unable to articulate any of life’s purposes, I rose from the table like a man of parts, settled my accounts, took the vaporetto from Accademia to the train station, where I rented a car, drove to Milan, boarded a plane for London and Detroit, and by that evening was dining at my local Coney Island talking about the Detroit Tigers with my brother. It was a shock to move so rapidly among the worlds.

Within six months I was married. Within a year I was enrolled in mortuary school. Soon after, the first of my sons was born. We moved to Milford when the family bought the funeral home there. It was June 13, 1974. My life was now rooted and full of purpose—family and funerals, taxes and accountants. It had direction—a wife, a job, another baby on the way, a future.

Poetry seemed a distant music.

In 1975 our daughter was born, in 1978 a second son. The business had grown from a hundred calls a year to a hundred and fifty. I was the president of the Rotary Club and the Chamber of Commerce. We bought a house next door to the funeral home and moved in with a mortgage and the dog. I was working and breeding and building as the young must do—networks, mergers and acquisitions.

By September 1979, my wife was pregnant with our fourth child. The funeral home was humming along. I bought a ticket and flew to Ireland for ten days because the ache inside me for Moveen had grown intolerable. It had been seven years since we’d gone there on our honeymoon. Nora had been to America, and we’d kept in regular contact. But I felt too distant from the place itself and the life that seemed important there.

Nora, now going seventy-seven, was holding her own against age and the weather and the powers that be. We drove up the Clare coast to Galway and bought books at Kenny’s—anthologies and literary magazines—Cyphers and Poetry Ireland. We had nights by the fire with neighbors and friends—talk and songs and stories. The Carmody sisters, schoolgirls then, brought their tin whistles. The Murray girls would come and sing. Nora Carmody brought news of the world. The dear Collins sisters, Bridey and Mae, J. J. McMahon, the Curtins and Keanes—each brought a party piece. When my turn came round—“now Tom,” J. J.’d insist, “now Tom, some Yeats”—I’d give out with it: “A Deep Sworn Vow,” or “He Wishes for the Cloths of Heaven,” or, if drink had been taken, “Broken Dreams.” One night I read from Death of a Naturalist, by the northern poet Seamus Heaney, and watched as those small farmers tuned their attention to the poems’ mention of “Toner’s bog, good turf, flax-dam, townland,” and an account of “when I first saw kittens drown, ‘the scraggy wee shits’” tossed into a bucket, “a frail metal sound.” This was a language they understood, full of things they were familiar with—hay barns and butter churns and “Turkeys Observed,” a “Cow in Calf,” an illegal bull—turned out in ways we’d never heard before.

“Good man for you, Tom,” J. J.’d say. “Fair play to you.”

There were love poems, family histories, a dark indictment of the neighborly racism behind the Famine, and one about the poet’s youthful fascination with open spring wells like the one in Nora’s lower field or across the road at Carmodys’ and about the self-consciousness the older man endures.

Now, to pry into roots, to finger slime,

To stare, big-eyed Narcissus, into some spring

Is beneath all adult dignity. I rhyme

To see myself, to set the darkness echoing.

It was all metaphor for the examined life of deep and hidden things—lineage, history, habitat, and language—that give life meaning, purpose, and resolve. The act of writing poems becomes the grown man’s mirror, looking into the wellspring of the self, the rhymes “set the darkness echoing.” This was, like Yeats, a collaboration of form and sound and sense—the deft balance of self-reference, examination, and manifesto; the willingness to use what is handy to order the world and make one’s own reflections relevant. And the evident faith in the language to make its own way, to shape its own course and fluency, like water—that close to nature—it made me feel alive to read it.

IN DECEMBER THAT year, up the street in the postman’s bag with the catalogues and Christmas cards came Michael Heffernan’s first slim book of poems, The Cry of Oliver Hardy. It was green and white and hardbound by the University of Georgia Press. It was sixty-one pages. It had his name on the front, his picture on the back, and inside he’d signed it, in broad blue ink strokes, on the title page. “Kennedy” was in it, and “The Plight of the Old Apostle,” “St. Ambrose and the Bees,” and some dozens more.

These poems that I’d seen years before, on his desk in his office in the house on Brown Road, had become a book for perfect strangers to pull from a shelf in a library or bookstore and read for themselves. The making public of this work he’d done in private—this publication made me wish that I had written some.

How, then, do you find it? In practice, you hear it coming from somebody else, you hear something in another writer’s sounds that flows in through your ear and enters the echo-chamber of your head and delights your whole nervous system in such a way that your reaction will be, ‘Ah, I wish I had said that, in that particular way.’

—from “Feeling into Words,” in Preoccupations

Heaney’s essay offered license, if not to steal, at least to borrow—poetic license—to sing along until the sound of my own voice emerged from what I heard ring true in others.

Finding a voice means that you can get your own feeling into your own words and that your words have the feel of you about them; and I believe that it may not even be a metaphor, for poetic voice is probably very intimately connected with the poet’s natural voice, the voice that he hears as the ideal speaker of the lines he is making up.

—from “Feeling into Words”

By now I was listening for the ideal speaker and had begun to think in syllables and lines, to construct them, to hear the tumblers of the language click into a fit of sound and image and utterance that unlocked my meanings and their own.

And I was “borrowing” with impunity, lip-synching the poets I most admired, plugging my own words into older forms—sestinas and villanelles—to see if I could make them “fit.” The rules, however arbitrary, made the rummage for the “right” word wider. For every right word gotten, there were dozens, maybe hundreds, handled, held up, considered, and rejected. It was necessarily messy work. The jettisoned words, scraps of phrases they fit into and later revised away, whole poems or parts of poems, freshly minted in late-night frenzy that would not, alas, survive the morning’s scrutiny, littered the workspace. The finished article, the thing well made, was a tiny diamond of a thing, extracted from the universe of words. There was about the enterprise, as the man hammering lobster would say years later, great debris and great delight, indeed.

ON HEFFERNAN’S instructions, I sent two poems off to John Frederick Nims at POETRY in Chicago. Yeats and Eliot and Wallace Stevens, Bishop and Berryman and St. Vincent Millay had published in POETRY. I figured a rejection from the best was better than from the least. But Nims took them. It was more encouragement than I needed. Then he took some more—one about our old dog, another about my grandmothers, a piece about man caught between competing instincts and cross purposes, immobilized by warring gravities.

I returned to Ireland, rented a typewriter from a shop in Ennis, and went to work on manuscripts in Moveen. Nora called it “the poetry business” and gave me a portion of her table on which to do it. I took the bike to Carrigaholt one day and posted off a manuscript to Eilean Ni Chuilleanain, an editor at Cyphers. I’d read and admired her work and the work of the consortium of Dublin writers—Pearse Hutchinson, Macdara Woods, and Leland Bardwell—who edited the magazine with her. Eilean took two poems. I was internationally unknown.

I was trying to organize a life balanced between the requisite and compelling work that paid the bills and the elective work of the imagination, between the rooted life in Milford and the life rooted in the magical language in Moveen, between a life organized around deaths and burials and a life that required what Heaney called “digging”—and what I thought of as disinterment. And while the everyday enterprise of the local businessman, husband and father, and citizen-at-large in a small midwestern place was one that suited me, the rich life of language, drawn from the idiomatic wellsprings of Moveen and its American cousins, informed by memory and imagination, was a constant preoccupation. Often these lives competed for time and attention. Time spent on one was subtracted from the other. Other times, each seemed bound to the other—the aching humanity, beautiful and sad, that populated the funeral home, often spoke in private, primal tongues.

When the father of a young girl who had died horribly began his daughter’s brief eulogy with “The thing you fear the most will hunt you down,” the grim pentameter of it stung my ears—da thing da fear da most da hunt da down—the awful iambs coded to his beaten, broken heart.

Sometimes I would see in my children’s eyes the knowledge that I was paying only a portion of the attention due their questions and curiosities, while carrying on an invisible word game with myself. The poem I was working on was called “Learning Gravity” and had to do with keeping balance.

THOSE EARLY PUBLICATIONS had occasioned an invitation from poets alive and thriving in Ann Arbor—Alice Fulton, Richard Tillinghast, Keith Taylor, and others—to join their monthly workshop. Since Heffernan, it was the first society of poets I’d known. It made me a better reader and writer and required me to contribute something every month. Most of those poets have become friends for life.

Early in the 1980s, Heffernan and I began corresponding in sonnets. We’d noticed that a three-by-five postcard held a title in caps and fourteen lines of text and could be mailed for fourteen cents. It seemed as though the Postal Service was imitating art. We conspired to carry on accordingly. He’d been divorced and remarried and had become a father by now. My marriage, unbeknownst to me, was on the brink of breaking. Heffernan would write:

MIDSUMMER LIGHT AS THE SOUL’S HABITAT

It wasn’t the turning of appearances

nor any of their exactions from the air

that made me think the afternoon was bees

or gangs of bears in rowdy robes of fur.

I hadn’t thought of this for any reason

and this wasn’t anyplace but my backyard.

Here was the flavor of an illusion

that stuck to my tongue like a hummingbird

beating its wings into a blur of hunger—

one of those tones from the soul’s undergrowth

where animals devoid of any anger,

lifting up bits of landscape in their teeth,

would turn to look around them where they were,

loosening their faces into shreds of fire.

In receipt of which I would return:

MARRIAGE

He wanted a dry mouth, whiskey and warm flesh

and for all his bothersome senses to be still.

He let his eyeballs roll back in their sockets until

there was only darkness. He grew unmindful

of the spray of moonwash that hung in the curtains,

the dry breath of the furnace, parts of a tune

he’d hummed to himself all day. Any noise

that kept him from his own voice hushed.

He wanted to approximate the effort of snowdrift,

to gain that sweet position over her repose

that always signaled to her he meant business,

that turned them into endless lapping dunes.

He wanted her mouth to fill like a bowl with vowels,

prime and whole and indivisible, O . . . O . . . O . . . .

Heffernan’s part of that year’s correspondence became a fair portion of his second book, To the Wreakers of Havoc, in 1984.

For my part, the sonnets were inklings of the storm that would become my family’s life in 1984 and end, in early 1985, with the dissolution of that marriage. I retained the house, the kids, the cat and dog, my day job and preoccupations. “Learning Gravity,” a longish poem, got published in halves—ninety-some lines in Boston and a hundred lines in Dublin—all in the same month of that awful year. It was, like everything then, divided. I tried to imagine the unlikely traveler who might, by coming upon The Agni Review in, say, the Grolier Book Shop in Cambridge, and taking the plane out of Logan Airport for Dublin and finding Cyphers in, maybe, Books Upstairs in College Green outside of Trinity, reconnect the dismembered portions of the poem, as I had, working back and forth between Moveen and Milford, between Ireland and America.

It was Heffernan, in the late summer that year, who gave me a list of editors and publishers and instructions to send them a book-length manuscript. To each I sent a sample—half a dozen poems—and a cover letter saying I could send them more. The first to respond was Gordon Lish, then an editor at Alfred A. Knopf, who requisitioned the whole collection. Within the week, I had a contract and a small advance. With the money, I planned a trip to Ireland.

In Dublin I’d arranged a visit with Eilean Ni Chuilleanain and her husband, Macdara Woods, who lived in Selskar Terrace, Ranelagh. I wanted to thank them for publishing my work. Their rooms were full of books and manuscripts—the toil of words was everywhere. Both of them were editing Cyphers and she was lecturing at Trinity and they had a three-year-old son named Niall. All of us had new books due out that year. After a night’s hospitality, Macdara walked me to the taxi stand. We spoke about Irish and American poets, about the ocean between them, about the interest on each side in the poetry of the other. Across the road a pub—the Richard Crosbie—was turning out the last of its late-night drinkers. It appeared in the title poem of Macdara’s book:

STOPPING THE LIGHTS, RANELAGH 1986

2.

It takes some time to make an epic

or see things for the epic that they are

an eighteenth century balloonist

when Mars was in the Sun set out for Wales from here

trailing sparks ascended through the clouds

and sank to earth near Howth

while dancing masters in the Pleasure Gardens

played musical glasses in the undergrowth—

they have used the story to rename a pub

to make a Richard Crosbie of the Chariot

Here, as in life, the epic makes way for the ordinary, the monumental becomes mundane. In the end—this is the good news and the bad—they might rename a pub for you.

WHEN IT ARRIVED, in January 1987, with a cover the color of the Ordnance Survey map, sixty pages, perfect bound, the creamy paper and crisp print, it seemed a thing quite separate from myself, a finished thing that could assume its thin place on the shelf where it might eventually explain to my sons and daughter what I was doing all those times that I appeared distracted. But Skating with Heather Grace became a kind of passport.

In the spring of 1988, The Frost Place in New Hampshire gave me a fellowship to Annaghmakerrig—The Tyrone Guthrie Centre for the Arts in Newbliss, County Monaghan. The woman I would soon marry, Mary Tata, moved in with my children so I could go. Guthrie’s old mansion housed, in monthlong residencies, a corps of working artists, writers, filmmakers and musicians. I met Conleth O’Connor there, a poet who would die in a few short years of drink—a sadness foreshadowed in his last book, A Corpse Auditions its Mourners. He took a copy of my book to his friend Philip Casey, the Dublin poet and fictionist, who showed it to his friend Matthew Sweeney, a poet from Donegal living in London. Sweeney showed the book to his editor, Robin Robertson, then at Secker & Warburg in London. They both showed up the following year to a reading I did at Bewley’s Oriental Café in Grafton Street. I was paid sixty punts, the going rate for visiting poets then, and sold some books to Books Upstairs. The next morning, I did an interview on the radio and read out poems all over the island. Macdara took me to Gerard Manley Hopkins’s grave at Glasnevin Cemetery in the Jesuit plot, then hosted with Eilean that night a party of poets in Selskar Terrace. It was three in the morning when Macdara drove Pearse Hutchinson to his digs and me to mine. We were the last of the night’s revelers. Our talk, somehow, got on to fly-fishing. Pearse cleared his throat in the backseat, then began.

“There is a grand story told on the subject of fishing by one of—may I say—your countrymen, from Clare, who reports the way the locals there use a goose for bait.”

“For shark?” I said, incredulous, the willing straight man.

“No, no. Actually for trout,” says Pearse in elegant deadpan.

The small coupe paused at the light. We waited for the punch line. When none seemed forthcoming, the car eased forth.

“Well,” I said, “that was one massive trout or one midget of a goose.”

“I suppose,” said Pearse and cleared his throat again, the don among the ignoranti, “but, of course, your man did not elaborate.”

I flew home grinning and determined to find the ancient text from which the poet had exhumed his story of the trout and the goose.

Macdara Woods followed my return to America, his first trip there, to do a series I’d arranged around the Midwest. When we met, in 1986, he’d been off the drink for four years. I’d seen him in his own local bar at home, The Hill in Ranelagh, where he gave up nothing of the society but refused the booze in favor of temperate drink. I’d been in trouble with alcohol for a while by then—

especially in the year since my divorce. It had turned on me and I wanted to stop. In late April of 1989, at a party to welcome Macdara Woods to Michigan, I sat in my study with Richard Tillinghast and Keith Taylor, quoting poems to each other and quietly killing a bottle of duty-free Black Bush I’d brought from Shannon two weeks before. The mix of Irish and whiskey and poetry and sociability had seemed an impossible alchemy to undo, but I knew that the whiskey was undoing me. It was Macdara Woods, a sober, sociable Irish poet, who modeled the possibility. The bottle of Black Bush we were after drinking was the last of the boozing I would have to do.

THE COLD

After the all hours drinking bout,

and the punchless acrimony,

he set off for the sea, on foot,

a good mile in the wind,

past zigzag lines of parked cars

and the disco din, past streetlights,

though if he’d needed light

the stars would have done—

down to the beach he wobbled,

a beercan in both pockets,

to sit on a rock and drink,

and think of his marriage,

and when both cans were empty

he removed his shoes

to walk unsteadily into the sea

and make for Iceland,

but the Atlantic sent him home again,

not a corpse, not a ghost,

to waken his wife

and complain of the cold.

“The Cold” is the first poem in Matthew Sweeney’s Blue Shoes—a book he’d launched in Dublin the night before we met. After my reading at Bewley’s, we traded books. Apart from the poem’s icy precision—its exercise in Ulster understatement—it includes two venues important to Sweeney’s work: the northern Atlantic coast of his Donegal upbringing and the ever-perilous domestic interior where men and women work out their lives. The poet-husbands of Sweeney’s work are ever on the brink of complete rejection, ever the architects of their own disasters.

Though full of fantasies (“Pink Milk”) and morbid curiosities (“The Coffin Shop”) and his famous hypochondria (“A Diary of Symptoms”), the poems of Matthew Sweeney that always return to me are those in which the poet is the passive, sometimes absent witness to his own domestic unraveling. Like the Irish epic antihero who is turned into a bird and must roam the ancient woods, this modern Sweeney is willing to watch his own imagined betrayals from a branch of an oak tree in the backyard.

It was at Matthew Sweeney’s invitation that I flew to London in late 1991 for a round of readings he’d arranged around the country. On a train ride to Evesham, he showed me the manuscript for his new collection called Cacti. In the title poem, a deserted man turns his house into a desert in hopes his woman will return. The text is edgy, like minimalist theatre, the space occupied by silence and wariness, the page dominated by white space. The poet arranges the furniture and lets his characters work away. Something fatal or fantastic seems always on the brink of happening.

I read in Evesham with Sean O’Brien, in Bristol and Loughbor-ough on my own, and made an off-season pilgrimage to Iona by train to pay homage to the Irish bardic poet St. Columba. I returned to London to meet up with my new wife, Mary, and to read at the Poetry Library with the Scots poet Jackie Kay in the South Bank Centre. From our room in the Charing Cross Hotel, we walked over the Thames on the Hungerford Bridge—the great city of the language and its river seemed full of poems and friends who wrote them.

Robin Robertson came to the reading and, in the bar of the South Bank Centre afterward, made known his interest in publishing my work. Years later, Christopher Reid of Faber & Faber, at a dinner at Robertson’s home, would comment on my finding an “English editor.” Our host corrected him: “He has a Scots editor with an office in London.”

EARLY IN 1992, my father died. Nora fell ill soon after and I found myself in Dublin early in March to do some legal work. Macdara and Eilean, as always, had a room and a roast dinner waiting, and a welcome. Eilean was scheduled to read that night in the Abbey Theatre in honor of International Women’s Day. The director of Poetry Ireland, Theo Dorgan, had arranged for several of Ireland’s finest poets to read, with the country’s new president, Mary Robinson, there to welcome them. Eavan Boland and Eithne Strong and Mary O’Donnell and Mary O’Malley and Julie O’Callaghan and Eilean—it was the first time I ever heard her read.

THE REAL THING

The book of Exits, miraculously copied

Here in this convent by an angel’s hand,

Stands open on a lectern, grooved

Like the breast of a martyred deacon.

The bishop has ordered the windows bricked up on this side

Facing the fields beyond the city.

Lit by the glow from the cloister yard at noon

On Palm Sunday, Sister Custos

Exposes her major relic, the longest

Known fragment of the Brazen Serpent.

True stories wind and hang like this

Shuddering loop wreathed on the lapis lazuli

Frame. She says, this is the real thing,

She veils it again and locks up.

On the shelves behind her the treasures are lined.

The episcopal seal repeats every coil,

Stamped on all the closures of each reliquary

Where the labels read: Bones

Of Different Saints. Unknown.

Her history is a blank sheet,

Her vows a folded paper locked like a well.

The torn end of the serpent

Tilts the lace edge of the veil.

The real thing, the one free foot kicking

Under the white sheet of history.

This poetry of icon and idol, of womanly priesthood and invention, made me think of Nora Lynch, in extremis on the other side of Ireland that night, and the powerful medicine she was said to have—the spiritual muscle to bless and curse, to divine out of the ordinary, the real thing.

It was always the business of Irish poets, making their way from barony to barony, parish to parish, to bless and curse with powerful words, the way Moses was said to have cured those bitten by vipers with a serpent of brass hung on a pole and exposed to the people of Israel.

And that line—“Bones/Of Different Saints. Unknown.”—put me in mind of the family reliquary, the great vault in Moyarta, with its gabled end and dark interior “lit by the glow from the cloister yard” when there’d been a death in the family; where Nora soon would be, with the bones of our common ancestors, Pat and Honora, dead a century, and her infant twin and her father. And my father and mother too recently dead, together in Holy Sepulchre, going to bone in the boxes I had put them in. These were the real things to me that night in the Abbey—these losses and pending losses among the last of my elders. Nora Lynch was dying in Moveen. Her history was “a blank sheet,/her vows a folded paper locked like a well.” Her only hope, and mine—language, poems, words—“The real thing, the one free foot kicking/Under the white sheet of history.”

When Nora died toward the end of that month, Macdara drove down from Achill Island in Mayo to be with us when we buried her. It was the done thing and a kindness.

In 1994, when a book was brought out by my Scots editor with an office in London, I was invited to readings in the United Kingdom and Ireland.

It was in Aldeburgh in East Anglia at a poetry festival that I first got a whiff of rare celebrity. The airfare paid for by my publisher, the car and driver waiting at the train station, the posters with my photo and name in bold Garamond, the banner over the High Street proclaiming the long weekend’s literary events, the welcome from the festival committee, and the chummy greetings of the other luminaries—each added a measure to the gathering sense of self-importance.

We all had put on our public faces. There was Paula Meehan from Dublin, Deryn Rees-Jones, a young and comely Liver-pudlian, Charles Boyle, then a junior editor at Faber & Faber. I was the American with Irish connections whose day job as a funeral director struck folks as sufficiently odd to merit mention in the local press. We were all poets of the book or two-book sort, on the edge of greater or lesser obscurity, to whom the keys to this North Sea-side city had been given in the first week of November 1995 for the Seventh Annual Aldeburgh International Poetry Festival. The tide of good fortune to which minute celebrities become accustomed was rising as we strolled the esplanade, Ms. Meehan and I, talking of friends we shared in Ireland and America, the rush of the off-season surf noising in the shingle, the lights coming on in tall windows of the Victorian seafront lodges. At one corner, a pair of local spinsters standing in their doorway called us in to tea and talk of literary matters. They had prepared an elegant spread of pastries and relevant questions about contemporary poetry and the bookish arts in general. We were, Paula and I, asked for what was reckoned expert testimony on verse and verse makers—the long deceased and the more recently published.

Then there were the panels and interviews, recorded for the local radio stations, and readings held in the Jubilee Hall, a vast brick warehouse that had been turned into a performance space by the installation of amphitheatric seating and microphones and stage lighting. The house was packed for every event, the sale of books was brisk, the lines at the signing tables long and kindly. They were so glad to meet us, so pleased to be a part of such a “magical event.” The air was thick with superlative and serendipity, hyperbole and Ciceronian praise. The dull advance of the darkening year toward its chill end had been momentously if only momentarily slowed by the “glow” of our performances. And after every event the poets—me among them—were invited to a makeshift canteen across the street above the city’s cinema. Teas and coffees, soups and sandwiches, domestic and imported lagers, local cheeses and continental wines were put out for the hardworking and presumably ever-hungry and thirsty poets who, for their part, seemed fashionably beleaguered and grateful for the afterglow among organizers and groupies. We were like down-market rock-and-roll stars on tour, clasping our thin volumes and sheaves of new work like the instruments of our especial trade, basking in the unabashed approval of these locals and out-of-towners. It was all very heady and generous.

A poet far removed from his own country, I felt at last the properly appreciated prophet. For every word there seemed an audience eager to open their hearts and minds. Strangeness and distance made every utterance precious. For while the Irish and Welsh and Scots were very well treated, and the English writers held their own, I was an ocean and a fair portion of continent from home and made to feel accordingly exotic and, for the first time in my life, almost cool.

Home in Michigan, a mortician who wrote poems was the social equivalent of a dentist who did karaoke: a painful case made more so by the dash of dullness. But here in England, I was not an oddity but a celebrity, being “minded” by a team of local literarians, smart and shapely women—one tendering a medley of local farm cheeses, another pouring a cup full of tea, another offering homemade scones, still another—the pretty wife of the parish priest—taking notes as I held forth in conversation with another poet on the metabolics of iambic pentameter and the “last time I saw Heaney” or “Les Murray” or some greater fixture in the firmament. And though I’d been, by then, abstemious for years, the star treatment was an intoxicant. The center of such undivided attention, I became chatty and fashionably manic, conversationally nimble, intellectually vibrant, generous and expansive in every way, dizzy and dazzling to all and every in earshot, myself included.

So it was when I espied, in the doorway of this salon, a handsome man I recognized as someone I had seen before, I assumed he must be from Michigan, since this was my first time ever in these parts. His dress was more pressed and precise than any writerly type—more American—a memorable face with a forgettable name, possibly a Milfordian on holiday or a fellow Rotarian, or a funeral director whom I’d met at a national convention who, having read about my appearance in one of the English dailies, had paused in his tour to make his pilgrimage to Aldeburgh to hear me read. It was the only explanation. My memory of him, though incomplete, was unmistakable: I knew this pilgrim and not from here.

I excused myself from the discourse with the churchman’s wife and made my way across the room to what I was sure would be his eager salutations. But he seemed to look right past me, as if he’d come for something or someone else. Perhaps, I thought, he did not recognize me out of my familiar surroundings and funereal garb. The closer I got, the more certain I was that he and I shared an American connection. I rummaged through my memory for a bit of a name, or a place or time on which to fix the details of our acquaintance.

“How good to see you!” I said, “And so far from home!”

Fully fed on the rich fare of self-importance, I was expansive, generous, utterly sociable.

I took his hand and shook it manfully. He looked at me with genteel puzzlement.

“I know I know you but I can’t say from where. . . ,” I said, certain that he would fill in the details . . . the friend we had in common, the event, the circumstances of his being here.

“Tom Lynch,” I smiled, “from Michigan,” and then, in case our connection was mortuary, “from Lynch & Sons, in Milford.”

“How nice to meet you, Mr. Lynch. Fines . . . Ray Fines. . . .” His voice was hesitant, velvety, trained; a clergyman, I thought. They were always doing these “exchanges” whereby one rector traded duties and homes for a season with another, the better to see the world on a cleric’s stipend. Or a TV reporter, the UK correspondent for CNN, maybe wanting an interview with the visiting American poet?

“Are you here on holidays?” I asked him.

“No, no, just visiting friends.” He kept looking around the room as if I wasn’t the reason for his being here.

“And where did we first meet? I just can’t place it,” I said.

“I am certain I don’t know,” he said, and then almost shyly, “perhaps you have seen me in a movie.”

“Movie?”

“Yes, well, maybe,” he said. “I act.”

It was one of those moments when we see the light or debouch from the fog into the focused fact of the matter. I had, of course, first seen him in America, in Michigan, in the Milford Cinema, where he’d been the brutal Nazi Amon Goeth, who shoots Jews for sport in Schindler’s List, and more recently in Quiz Show, where he’d played the brainy if misguided golden boy of the American poet Mark Van Doren. He was not Ray Fines at all. He was Ralph Fiennes. His face was everywhere—the globalized image of mannish beauty in its prime, and dark thespian sensibility, privately desired by women on several continents and in many languages, whilst here I was, slam-dunked in the hoop-game of celebrity before I’d even had a chance to shine. Across the room I could see the rector’s wife, watching my encounter with the heartthrob. She was wide-eyed and blushing and expecting, I supposed, an introduction.

A contortionist of my acquaintance, whose name would not be recognized were I to use it, though he has accumulated some regional fame for something he does with thumbs, once theorized that if the lower lip could be stretched over one’s head, and one could quickly swallow, one could disappear. Never had I a greater urge to test the theory than that moment in Aldeburgh. I felt my lower lip begin to quiver and tried to calculate its elasticity, but all I could manage was an idiot grin. Mr. Fiennes, apparently a well-bred man, said nothing further and smiled kindly. I affected a hasty retreat, as if to make final edits and further fine-tunings to the reading I would be giving, alas, anon.

Eventually I read my poems to the many dozens assembled in Aldeburgh, and their applause, such as it was, was a delight and surprise. To have the work one has done in private considered by strangers in far places remains for me an unexpected gift. To hear new poems said out loud in the voice of their makers has kept the language alive for me.

I’ve read with Paula Meehan in England and Ireland and Michigan and heard the hush that widens in the room when she begins:

Little has come down to me of hers,

a sewing machine, a wedding band,

a clutch of photos, the sting of her hand

across my face in one of our wars

when we had grown bitter and apart.

Some say that’s the fate of the eldest daughter.

. . . and heard the breath go out of those that hear it, when seven or eight minutes later, Paula brings “The Pattern” to its close—peace made, love told to the ghost of a mother who died too young.

And I’ve read with Dennis O’Driscoll, surely one of Europe’s great men of letters. A civil servant for more than thirty years, he works for Irish Customs in Dublin. Apart from being among the most widely respected and widely published Irish critics of poetry, he is the author of seven collections of poetry, a volume of prose, and dozens of uncollected reviews, profiles, bits of literary biography. His poems are refreshingly liberated from the mythic-pastoral tributaries of his countrymen. His work is immediate, urbane, free of adornment, and uniquely citified as in this piece from Weather Permitting:

THE CELTIC TIGER

Ireland’s boom is in full swing.

Rows of numbers, set in a cloudless blue

computer background, prove the point.

Executives lop miles off journeys

since the ring-roads opened, one hand

free to dial a client on the mobile.

Outside new antique pubs, young consultants

—well-toned women, gel-slick men—

drain long-necked bottles of imported beer.

Lip-glossed cigarettes are poised

at coy angles, a black bra strap

slides strategically from a Rocha top.

Talk of tax-exempted town-house lettings

is muffled by rap music blasted

from a passing four-wheel drive.

The old live on, wait out their stay

of execution in small granny flats,

thrifty thin-lipped men, grim pious wives. . . .

Sudden as an impulse holiday, the wind

has changed direction, strewing a whiff

of barbecue fuel across summer lawns.

Tonight, the babe on short-term

contract from the German parent

will partner you at the sponsor’s concert.

Time now, however, for the lunch-break

orders to be faxed. Make yours hummus

on black olive bread. An Evian.

For someone who has been dropping into Ireland for three decades now, such a poem is indispensable—capturing as it does the full sweep of changes in the Irish mindset and economy in nine brief stanzas, twenty-seven lines. Better than any social or cultural study, “The Celtic Tiger” charts the distance from the meat-and-potatoes culture of the past century to the “hummus on black olive bread” and designer-water culture at the turn of the second millennium. It comes from a man who came of age when a civil-service job meant security. To work for the government or a bank, to teach or join the reverend clergy—these were the best and brightest future jobs in the 1960s and 1970s and the ones most manifestly left behind in the IT, EU, Irish Boom of the 1990s. O’Driscoll, born in 1954, in Thurles, County Tipperary, began working in 1970 for the Estates Division, collecting death duties before rising to his current assistant principal rank with the International Customs Branch.

His colleagues, no more interested in his poetry “than another fellow’s greyhounds,” nonetheless take notice when RTE sends a cab to bring O’Driscoll to and from the lunchtime Arts Show on the radio where his commentaries on books and writers are broadcast around the country. The man who was the Irish Customs delegate to the EU in 1996 was the editor for POETRY Magazine’s Irish Poetry Issue in 1998. When we read together for the Lannan Foundation in Santa Fe in the spring of 2001, he allowed as how we should call it “Death & Taxes,” in observance of our day jobs.

The army of poets who make poems in English never falls short of volunteers. And though there is some sniping in the ranks, some friendly fire and begrudgery, at the end of the day they all bed down with words still ringing in their ears.

In the years since I began writing poems, there have been wars and upheavals, disasters and deaths, drunks and recoveries, marriages and children. Presidents and prime ministers have come and gone. There are peace accords and suicide bombers, more terror and technology. The news of the day most days repeats itself. It seems the same war, the same outrage, the same sadness. The fresh word that is poetry remains. In the best and worst of times, it has been the work of poets that sees us through.

I’VE OPENED THE house to writerly friends. They stay for days or weeks or months on end. I’ve lost count of the projects finished there, or started. Early on, I tried to say that everything from Moveen West back to the Loop belonged to me—the flora and fauna and history, the stories and the people and geographies. “You can have anything out the kitchen window east,” I’d tell them. “The rest is mine.” Writers are such amiable thieves, they’d go off with anything and call it their own. I didn’t want some visiting writer taking the things I’d staked out years ago—Dunlicky, the Bridges of Ross, the story of lovers at Loop Head, the underground river that divides Moveen West from East, the characters there both living and dead. But then, what was I if not a visiting writer, stealing the images and stories I’d heard, telling them over and over in my own voice? So I gave up. The only rent they’d owe me would be words.

I had the Kennys up in Galway make a book—a largish binding of blank pages, with Lynch—Moveen West on the cover—and wrote the lease agreement on the first page inside.

RENTALS LEDGER

Des Kenny up in Galway made this book

of pages fit for ink and acid free

and sewn into a leather binding. He

put Lynch—Moveen West on the cover. Look,

there’s whitespace left for the likes of you

so if you’re a writer the rent is do.

Pay Breda Roche coin of the realm for coal

and turf, fresh linens, clean towels. The phone’s

on the honor system. Pay as you go.

But leave this absentee landlord poems,

paragraphs, sentences, phrases well turned

out of your own word horde and what you’ve learned

here in these ancient remedial stones

where Nora Lynch held forth for ninety years,

the last two decades of them on her own.

Alone by the fire in the silence she

recited the everyday mysteries

of wind and rain and darkness and the light

and sang her evening songs and sat up nights

full of wonder and reminiscences.

If you hear voices here the voice is hers.

She speaks to me still. If she speaks to you,

ready your best nib. Write what she tells you to.

There are bits of stories by fictionists from Glasgow and Dublin and Amsterdam. There are verses by Irish and other poets, from the U.K. and the Continent, the Americas and the Antipodes. Philip Casey left his funeral instructions.

THE WINDFALL OAK

On Webster’s isle find a windfall oak

and hollow it to my measurements.

Make sure I go in my casual clothes.

No fancy lining, just wood and bark,

the rough-cut halves secured with rope.

Seal it if you must with wax,

then form a circle around my tree

to celebrate my love and laughs,

my fountain pen, my pain, my hope

in well-wrought verse and song, and ceilidh.

Then plant this sapling in the earth.

Linda Gregerson left “Cranes on the Seashore” to let me know how it was for her:

I.

Today, Tom, I followed the tractor ruts north

along

the edge of Damien’s pasture. I missed all the

dung slicks but one. The calves did not judge me

or, comely

darlings, judged me benign. The ditches

and the token bits of barbed wired weren’t, I like

to think,

intended to halt my trespass much more than they

did. The hedge-crowned chassis might have been one

of my father’s

own. And then the rise, Tom, the promised

North Atlantic, and I’m fixed.

The poem plays out, in three more sections, the activities of the poet’s two young daughters who have hiked with her up Sonny Carmody’s field across the road, to the ridge overlooking the ocean that bounds Moveen. Megan is trying to draw the cliffs. Emma is enchanted by Damien Carmody’s Holstein calves, the smallest of which, slow to the bucket of feed, she reckons at first is “simply less greedy.” The images of motherly understanding and daughterly innocence are calming and sweet. But in between these ruminations, the poet retells the awful story she has read in the section of that week’s Clare Champion called, “Turning the Clock Back,” which reprints every week something from the archives of fifty and a hundred and one hundred twenty-five years ago. It is the story of two girls at a nearby beach on a June evening in 1874, “washing skeins of new spun wool.” They are, the paper reports, mistaken for cranes by a young Mr. Dowling who, from some distance, takes aim with his gun and shoots them both. It is a horrible miscalculation.

Of Mr. Dowling’s youth and upright family

the writer

cannot say enough (his obvious

promise, their moneyed remorse);

Is it the landlord’s son who has shot the local girls “both in the employ of the Leadmore farm”? Who else would have a rifle and “moneyed remorse”? The disaster seems entirely too natural, set as it is in the pastoral of seaside, field and farm. Once out, the awful facts must multiply. Innocence is lost. The holiday is over. It is time to go. The rent, as always, must be paid.

God

keep us from the gun sight. Here is

one

for the landlord and one (we’re almost

gone) for the road.

Breda Roche leaves the key under the mat and a fire down, fresh milk in the fridge, some eggs and scones. She leaves the big book on the table to collect the rents.

The house that was left to me is full of ghosts and their good voices. The talk is circular and intertwined. Everyone’s connected. Each party piece inspires others.

IF LIFE IS linear, our brief histories stretched between baptisms and burials, and the larger history tied to events that happen in a line: and then, and then, and then, and then . . . poetry is the thing that twists history and geography and memory free of such plodding. Everything is tributary, every image and experience capable of turning on itself a hundred different ways.

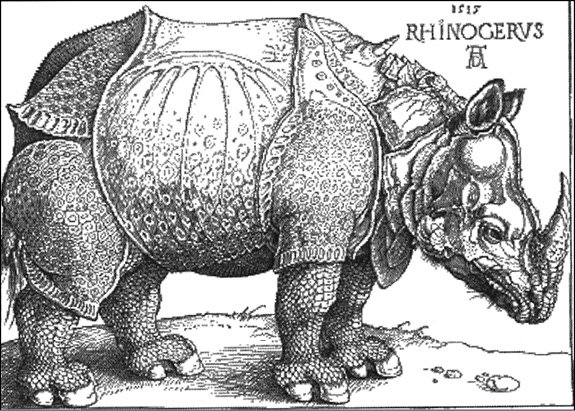

It’s all a metaphor: the house with its voices, the book of rents, the poet hammering lobster on the flagstone floor. The Heaneys and Reids are dining on fresh catch in Moveen. “What I remember is the problem of cracking the backs of the lobsters . . .” the Nobel laureate writes. “The Reids were in residence in the cottage and had acquired the creatures wherever: mighty movers, a match for Dürer’s rhino any day.” And we are moved and mightily—to see the armor cladding and the claws, like cloven pincers, and the hungry dinner guests’ dilemma.

But Dürer never saw a rhino and made his famous woodcut out of words found in a letter that came from Lisbon to Nuremberg with a hasty scribble of the awful ungulate—the four-footed beastie, as it was called—an alien species from another world, a gift from the king of Cambodia to the king of Portugal for the Royal Zoo, Rhinoceros unicornis, which would, as history has it, some years hence be lost at sea with all hands on board, en route to the care and keeping of His Holiness in Rome. None of which matters. They are only facts. What is remembered is the image wrought from words, the oddly lovely heavy-breathing thing. Five hundred years later, it is still, for all its errors, for all its flaws, the thing we see when we hear “rhino.” We see best what we say in words. “Fast, jolly and cunning,” Dürer wrote, describing the creature in his border notes.

It’s all a metaphor: the poet, like a rhino, on all fours, “beyond all adult dignity,” “fast, jolly and cunning,” banging at the boiled lobster with a hammer on the stone floor, like hammering for diamonds in coal, gold in rock, the pearl in the oyster, the precious bit among the many pieces. “Did we splatter the shells? I think we may have.”

It’s all a metaphor: the sense, he reports, of “a feast that had been fought for,” whereby the lobster is linked to all hard-won feeds—the fish hauled from the ocean, the plucked hen, the things we grow and gather in, the hunted, slaughtered, butchered things we cook and eat—all metaphor for what we need: the feast, the common meal, the open table and celebration—all metaphor for life’s work in words, for life’s work, for life, for the images and talk among us all, living and dead, “great debris and great delight.”

“POETRY,” THE POET Heaney says the poet Auden said, “is what we do to break bread with the dead.” Is it anything, I wonder, like hammering lobster? “Rhyme and meter,” Heaney adds, “are the table manners.”

He’s reading at the University of Michigan.

Auden taught here in Ann Arbor briefly, after moving to the United States the year that Yeats died in France, the year Heaney was born in the North of Ireland. And Heaney’s friend, the great Russian poet Joseph Brodsky, taught here when he was exiled from Russia in 1972. He died on the same day Yeats died—January 28—almost sixty years later.

Some months before Yeats died, he gave, in “Under Ben Bulben,” directios to his countrymen:

Irish poets, learn your trade,

Sing whatever is well made,

Scorn the sort now growing up

All out of shape from toe to top.

When Auden got word about Yeats’s death, he wrote his famous elegy, “In Memory of W. B. Yeats,” in which he gives his own directive, borrowing the dead man’s “table manners”:

Earth, receive an honoured guest:

William Yeats is laid to rest.

Let the Irish vessel lie

Emptied of its poetry.

When Brodsky died, too young, too soon, in 1996, Heaney borrowed for “Audenesque” the rhyme and meter that Auden had borrowed from Yeats, and Yeats from Blake, and Blake from, maybe, a children’s rhyme.

Joseph, yes, you knew the beat

Wystan Auden’s metric feet,

Danced to it unstressed and stressed

Laying William Yeats to rest.

And here it is April, some years since. Heaney will read in Sligo this year at the Yeats International Summer School. The Belfast that Joseph Brodsky saw when he wrote “Belfast Tune” (“Here is a girl from a dangerous town/she crops her dark hair short/so that less of her has to frown/when someone gets hurt”) is blooming with daffodils and a kind of peace. Auden’s poem “September 1, 1939,” written at the start of World War II, has become suddenly famous since the horrors of September 2001. One commentator in the Times Literary Supplement writes, “Auden’s words are everywhere.” (“I and the public know/what all schoolchildren learn,/those to whom evil is done/do evil in return.”) After sixty-five years, it still rings true.

Heaney turns sixty-five this month. This June will mark the hundredth Bloomsday and Kavanaugh’s Centenary is on this year.

The language gives us much to celebrate. So I install the ancient meter in my ear—What an undertaking Tom/Tump-ti tump-ti tump-ti tum—and go out for a walk, to hear what happens.

Once a school boy in West Clare,

Stood to ask me when and where

I got my “poet’s license”?

“Hush,” the teacher seethed. “Silence!”

The laughing class went quiet.

The silence echoed. “Try it,”

I whispered, to embolden.

“We’re born with it,” I told him.

Next day in the morning mail:

Mister, do I pass or fail?

‘Tweedle dum and tweedle dee

Had to go out for a pee!’

Pass, I wrote, Good man for you!

Reckoning good p’s and q’s

Dumb fellows who’ll never rhyme

Whilst dee and pee’ll tweedle fine.

That boy’s face, in a classroom in Cross Village, between Carrigaholt and Loop Head, the look of play and portent in his eyes, of mischief and hidden meanings, the sure sense he had that words were gifts and a way with them was powerful medicine put me in mind of what I first found in Ireland at the fire in Moveen where Nora strove among her home and kitchenwares and her brother Tommy with his cattle and the land, at a life that seemed a series of feasts worth fighting for.

Great debris, delight indeed:

So it is with this life. We

Hammer at the moment till

All that’s left is memorable.