In the dark after-midnight hours of September 22, as Bishop Whipple sat in a tent with General McClellan and talked of God and war, Little Crow and several of his warriors stood atop a rise just south of the Upper Agency and peered into the distance. To the southeast, clearly visible across the undulating ground, they saw the fires of a military force gathered for the night around a small prairie lake along the reservation road. Colonel Sibley had finally moved north to meet the Dakota in their own territory and now the Dakota were ready to be met. In their view, the white commander seemed to have selected the site with an eye toward maximum vulnerability, and soon the news got even better, when silent scouts returned to announce that the whites were moving with no advance cavalry and had posted their pickets close in, so that approaching the camp in the night would present little difficulty.

The conflict that many whites were calling Little Crow’s War was now more than a month old. The Dakota had hit hard at the Lower Agency and Birch Coulee, had twice failed to take Fort Ridgely, and had caused the evacuation of New Ulm. A few hundred men roaming across the prairie had taken as many as four hundred lives and all but emptied the state’s southwestern quadrant. Still, only now were Dakota warriors and white soldiers primed to engage in something resembling a conventional battle. Scouts reported that Sibley was traveling with cannon and supplied with a lengthy wagon train, on guard but seemingly ignorant of the true extent of his danger. Little Crow was finally presented with an opportunity to “make war after the manner of white men,” as he had put it, commander against commander meeting in battle between armies. If he was going to deliver the bite that would cause the white hand to pull away and give him time to maneuver or to negotiate, it needed to happen now.

The Dakota leaders knew that they could depend on two or three hundred men to fight; beyond that number, allegiances and stomach for battle were unreliable. One morning earlier, upon learning of Sibley’s location, Little Crow had instructed his camp crier, Round Wind, to call out his orders: every man fit to wield a weapon must prepare to fight or be killed by the men of the wartime tiyotipi for not fighting. The threat was made in earnest, as was a promise: great honor awaited any warrior bringing back the white army’s colors or the scalp of Colonel Sibley. All through the night and early morning, hundreds of warriors—some anxious for battle, some anxious to avoid battle—had moved out of the camp. As the war party crossed a creek, each man handed a stick to a warrior stationed by the side of the road, and in this way the force tallied its strength: 738 sticks; 738 men to face Sibley’s army of more than 2,000.

Little Crow and his fellow chiefs now held council on their hilltop command post northwest of the site. They knew that the field Sibley had chosen, a few hundred yards off the government road, was not so much different than the ones at Fort Ridgely or Birch Coulee, with ample concealment available along a series of shallow hollows and creeks on three sides. Little Crow wanted to launch a raid that very night with a small force, swift and fierce, but a spirited council on the spot finally created consensus for a more traditional early-morning action. The plan was simple: when Sibley and his forces left their camp, presumably not long after dawn, their path along the government road would take them over the Yellow Medicine River, which was lined with cottonwoods and thick underbrush; here one prong of an ambush would begin, with another large group of warriors descending on the rear of the column and its supply wagons as it crossed a smaller creek running northward out of the lake. Sibley would be trapped between two watercourses with his men in a long thin line, his provisions easily targeted and his route of escape uncertain in any direction.

Moving quickly and making no noise, the Dakota set themselves in place as the moon lowered in the west, some along the river to the north, some near the creek running out of the prairie lake, others in the tall bluestem grasses along the government road. From their hiding places his warriors could hear the white soldiers talking, singing, and laughing. And when dawn came, they could see Sibley taking his time getting ready to move, oblivious to seven hundred men watching his forces and ready to attack. The sun rose in the sky, but still Sibley’s men did not start, and still Little Crow waited. Today was the day. He could afford to be patient.

For weeks the leaders of the friendly Dakota had been looking for an opportunity to bring the white women and children under their protection, and now, with the Dakota warriors gone to face a formidable opponent, they had their chance. As soon as Little Crow and his force of 738 men disappeared down the road from their camp near Red Iron’s village, Paul Mazakutemani and other peace party leaders crossed over to face what few hostile Dakota remained and demanded that the prisoners be released to them. Threats followed, but the scales had tipped and the white captives were allowed to go.

Once most of the captives had been transferred to the friendly camp, an armed patrol began while the women and children and older men dug deep circular trenches inside and outside of the tepees, a custom born of countless encounters with Ojibwe war parties. If the battle was lost and Little Crow or the warriors of the tiyotipi returned with annihilation in mind, these trenches might keep the inhabitants of the friendly camp alive when the firing began. A final contest might take place amid the Dakota as well as out on the prairie, an understanding that spread among the captives and gave them the energy to move earth with only small spades or even their hands. They had been threatened so often by Little Crow and the men of the tiyotipi that it had become difficult to distinguish real danger from boasting. But this moment, they could tell, was different.

For weeks Sarah Wakefield and the rest of the captives had watched as hundreds of individual agendas played out among the Dakota: those bent on killing whites, those determined to save whites, those aiding whites in order to receive more favorable treatment at the war’s end, those resentful of their prisoners, and those in physical distress due to sickness or age and simply struggling along, paying little attention to the whites among them. Each captive had her own particular tormentors and protectors. How much rape occurred will never be known—after the war, many stories were told, though very few incidents were verified by individual testimony—but the perceived threat had been ever present. Now out of the confusion and fear rose a new sense of clarity built on the knowledge that white soldiers were finally nearby. The rush to enlarge the friendly camp also reunited friends and neighbors and brought news of missing husbands and children, sometimes gruesome tales of short flight and death and other times heart-lifting stories of escape.

Sarah Wakefield was not among this sudden, desperately hopeful community of friendly Dakotas and their new charges. For thirty-six days she had lived in fear for her own and her children’s lives, and for thirty-six days Chaska had risked his own to keep her safe. Her hair, once auburn, was now white, and her hefty frame had shrunk by forty pounds. During and after the long retreat from New Ulm, her story continued to be one of squaws carrying her children when she tired, concealing her under blankets when violent warriors entered the camp, and making garments for her and her children so that she would not so obviously stand out. Again and again Chaska had turned away other Dakota men demanding Sarah’s sexual attentions by saying that she was his wife, a claim that drew ever more vicious innuendos from other whites, who viewed her not as a resourceful and adaptable survivor but as an Indian lover enamored of her own captivity.

The series of staggered removals and stretched-out days had taken her through the Upper Agency, to the Rush Brook camp near the Hazelwood Republic, and then onward until Little Crow had halted them at a large plateau described by one captive as a “howling wilderness” twenty miles north of the Upper Agency, near Red Iron’s village and the rest of the Sissetons and Wahpetons who in so many cases wanted nothing to do with the war. All the while, somewhere behind them, Sibley’s column had approached at a pace Sarah found maddening. She wrote later that “the Indians made much sport of the slow movements of Sibley; said the white people did not care much about their wives and children or they would have hurried on faster.” Sarah seemed not to understand or believe that the advance of white soldiers might push Little Crow or the wartime tiyotipi toward the desperate step of killing the captives; she expected Sibley to make battle, and finally, when the camp crier called out Little Crow’s instructions that all able-bodied men must rouse themselves to fight, she understood that her wish had been granted. But as the men prepared to head off for the Upper Agency, a new set of fears emerged.

“I tried to urge Chaska not to go,” she wrote, “but he said Little Crow would say I had prevented him, and that he would destroy us both.” Before leaving to face Sibley’s men, Chaska begged Sarah to stay with his mother and not move to the friendly camp with the other captives; he was worried that the whites and their new protectors would be destroyed should the battle go badly. That she took his advice, when almost all of the other captives were frantic to make the move, was a sure sign of the extraordinary bond that had formed between them. Sarah was left as one of only three white women in the hostile camp, by her count, another circumstance that the more vindictive of her fellow captives would eventually add to a long list of indictments against her character and conduct.

Later that day, both camps, hostile and friendly, began to hear the report of gunfire and cannonade miles away; a sound, wrote one mixed-blood captive, that was “as sweet as the chimes of wedding bells to the bride.” As the battle raged, a mixed-blood courier carried a letter from Sibley into the two camps with instructions to make sure its contents were broadcast to all of the remaining Dakotas, mixed-bloods, and whites wherever they might be found.

When you bring up the prisoners and deliver them to me under that flag of truce I will be ready to talk of peace. The bodies of the Indians that have been killed will be buried like white people and the wounded will be attended to as our own; but none will be given until the prisoners are brought in … A flag of truce in the day-time will always be protected in and out of my camp if one or two come with it.

Sibley sent a separate letter to peace party leaders telling them that “I have not come to make war upon those who are innocent, but upon the guilty,” leaving it to the Dakota to interpret what he might mean by “innocent” and “guilty.” Unbeknownst to the Dakota in the riverside camps, Sibley also sent a message farther north to the powerful village chief Standing Buffalo, assuring him that he was not aiming to make war on the Sisseton and Wahpeton, but also including a warning to “advise your bands not to mix yourselves together with the bands that have been guilty of these outrages, for I do not wish to injure any innocent person; but I intend to pursue the wicked murderers with fire and sword until I overtake them.”

Early that evening the warriors began to return, one at a time or in small groups, “bearing wounded, singing the death song, and telling the tale of defeat.” The lamentations of Dakota mothers and wives were loud enough to be clearly heard in the friendly camp, half a mile away. For Sarah, secured in Chaska’s tepee at the edge of the hostile camp, the cacophony pressed in like a physical force. “Any one that has heard one squaw lament,” she wrote, “can judge the noise of four or five hundred all crying at once.” Whatever happiness she felt at the news of Sibley’s victory was more than tempered by the grief of the women who had cared for her all these weeks and her fear that Little Crow and his warriors were on their way back to kill all of the captives.

Soon enough the scale of defeat was made plain. Luck had turned against the Dakota when the action opened prematurely, after a party of white soldiers foraging for potatoes had driven their wagon off the road and straight across the prairie grasses, where they nearly ran over a small detachment of Dakota scouts prone in the grass. The first gunshots roused Sibley’s camp and put the initial action out of the reach of many of the warriors, especially those positioned on the northern edge of the site. Little Crow’s problems also came from within. Many of the Dakota, coerced into the battle, had positioned themselves outside the main action. Some had even raised white flags. Some of those who did join in combat testified later that they fired their weapons into empty space, a contention that in many cases was surely true. Still, the fighting between whites and the core of committed Dakota warriors was fierce, and only three hours later, after a determined stand and bayonet charge by the Third Minnesota Regiment, did the Dakota break and retreat. Behind them fourteen white soldiers lay dead and mutilated, along with twenty Dakotas, whose bodies were soon scalped in retribution, much to Sibley’s public indignation.

According to multiple accounts, Little Crow returned in a wrath and raised his voice to address the entire camp.

Seven hundred picked warriors whipped by cowardly whites. Better run away and scatter over the plains like buffalo and wolves. To be sure the whites had big guns and better arms than the Indians and outnumbered us four or five to one, but that is no reason we should not have whipped them, for we are brave men, while they are cowardly women. I cannot account for the defeat. It must be the work of traitors in our midst.

The Battle of Wood Lake represented the final exchange of massed gunfire in the Dakota War. The next day, Chaska reported to Sarah that Little Crow was getting ready to depart for the West and added that five mixed-bloods had been charged with taking her many miles across the prairie to Sibley’s forces under a flag of truce. Sarah refused the offer, assuming that she would be killed by one of Little Crow’s warriors as soon as she set foot out of the hostile camp. Two village chiefs allied to Little Crow then assured her that John Other Day, a Christian Dakota and scout for Sibley, would be coming to retrieve her himself. In the meantime, they said, they wanted her to write down an account of her treatment by Chaska and her other protectors. “I told them it was very foolish for me to write, for I could tell the people just as well as to write, and I began to be suspicious of some evil,” she said later. “I was afraid they would murder us and hide our bodies, and carry our notes to the Fort.” But she did write the note, though she refused to budge until the hostiles were gone.

When she understood that Chaska was right, that Little Crow was busy making preparations to leave, Sarah changed out of her Indian dress and offered tearful thanks to the Dakota women who had cared for her. Chaska’s mother cursed Little Crow’s name and said, “You are going back where you will have good, warm houses and plenty to eat, and we will starve on the plains this winter.” Several of Sarah’s protectors “cried over James and begged me leave him with them,” as “he was a great favorite with the Indians all the time I was with them.” Led by Chaska, she held James and one of Chaska’s cousins carried Nellie as they walked over to the friendly camp, where they mounted a small hill and sat down under an American flag to watch as Little Crow’s train began to depart, piece by piece. After a time, when most of the procession had disappeared over a rise to the northwest, Chaska and his cousin said good-bye and walked back down the hill toward their tepees. George Gleason’s dog, another survivor, trotted beside them.

Cecelia Stay Campbell, daughter of the mixed-blood interpreter Antoine Campbell, later wrote an account of her father’s attempt to persuade Little Crow to surrender on September 24, the final day of Sarah Wakefield’s captivity. She described how her father found Little Crow inside his tepee, surrounded by a guard of his most trusted soldiers, all in battle dress and leaning on their guns as they listened in silence. The two men, old friends, sat facing each other on blankets as Little Crow announced his intentions to leave for the western plains and asked if Campbell had any final requests.

“Yes, cousin, we are most safe now,” Campbell said. “General Sibley will be here soon, and I would like that you and your warriors would give yourselves up.”

In response, Little Crow only laughed and said that he would consider surrender “if they would shoot me like a man, but otherwise they will never get my live body.”

A morning of councils had followed, during which leaders of the tiyotipi argued for continuing the war and reclaiming the captives, killing any friendly Dakotas who refused to cooperate. Even now, Little Crow and the young men of the soldiers’ lodge continued to operate more in parallel than in concert, acting as a kind of two-headed leadership, each taking its own counsel and issuing its own edicts. But no one in either circle believed that Sibley would honor any agreement of surrender. As Samuel J. Brown reported, “Little Crow called all his warriors together and told them to pack up and leave for the plains and save the women and children, the troops would soon be upon them and no time should be lost. ‘But,’ he said, ‘the captives must all be killed before we leave. They seek to defy us,’ he went on, ‘and dug trenches while we were away.’ ” This was Little Crow’s final threat in six weeks of threats directed at his prisoners. He had acted on none of them and would not do so now. In any event, according to Brown, the friendly Indians “simply laughed at Little Crow’s bombastic talk” and dared his warriors to try to take the captives away from them.

Six weeks earlier, when four young men stood in front of his tepee and reported their act of violence in the farmsteads to the north, Little Crow had understood what war would mean. When members of the wartime tiyotipi and other men returned after the first attack on the Lower Agency and reported a killing spree in the settlements that had taken hundreds of white lives, including many women and children, Little Crow had understood that retribution would fall not just on the perpetrators of these acts but on all Dakotas. Yet he had continued to offer the young men his leadership, however reckless their actions and however little they heeded his instructions, for he believed that the day of reckoning was bound to arrive no matter how accommodating and pliable he might be. It had taken Little Crow most of his fifty-two years to reach the unalterable conclusion that whites would accept only one outcome: the frontier must be emptied of the Dakota, whether that meant destroying them, driving them away, or making them abandon the social, cultural, and religious customs that made them Dakota in the first place.

Exhausted from battle and council, his legendary stamina tested as rarely before, Little Crow spoke ruefully to the mixed-blood Sisseton Susan Brown, mother of Samuel J. Brown and wife of the former Indian agent Joseph R. Brown. Knowing that government soldiers would arrive from the battlefield in days, if not hours, Little Crow told her that he had decided not to follow through on his threats against the white captives in his camp, though he would bring a small number of them with him as hostages. A dispatch arrived that afternoon from Colonel Sibley demanding that Little Crow surrender the captives and promising that he would talk to the chief “like a man,” but Little Crow paid it no mind. Facing his men, he made one last speech and then directed that a message be delivered to the white commander: “Sibley would like to put the rope around my neck, but he won’t get the chance.”

When he last looked down into the Minnesota River Valley, Little Crow saw the final forsaken homeland of his life. Whatever good-byes Little Crow did or didn’t say, he knew that he left as a man hated by whites and by many Dakotas. As a young man, as Taoyateduta, he had ridden into the West within a rhythm of hunt, harvest, and hibernation. Now there was no allegiance to the seasons. He knew how different the territory up and over the Coteau des Prairies was, how cruel its cold winds could be, and how many white soldiers would follow in his wake as soon as the James and Missouri rivers opened for navigation in the spring.

His mind had already turned to stratagems involving his western kin—the Yanktons, Yanktonais, and the numerous Lakota—and the British outposts in Canada. No longer was he thinking of reservations, of large farms tended in long rows, of white books about a white God. For centuries the Dakota had been on the move in one way or another, first arriving out of the Great Lakes regions, then settling down in the woods and valleys of the Upper Mississippi River, then concentrated on their ten-mile-wide prairie reservation. But only now, in the moment Little Crow spurred his horse, the Dakota diaspora began, one that would scatter not just the Mdewakanton and their allies but many of the Indians of the Northwest, most of whom had played no part in the Minnesota conflict. Little Crow was wise and experienced enough to understand what his present actions might mean, but exactly how and where that scattering would take place he couldn’t have known. For the time being, he felt only his own motion, straight into the coming winter snows.

Sarah Wakefield assumed that the next day would mean delivery from her captivity and a full meal, a change of clothes, and a chance to wash, free of the fear and uncertainty of the past six weeks. Instead, Sibley and his men did not appear, and she spent twenty-four hours terrified that Little Crow would return to kill the captives after all. Reports trickled in that Sibley’s army was sitting at the Hazelwood mission station, just ten miles away, digging sentry pits and, for whatever reason, conducting a grand dress parade. The wait, after what Sarah considered a series of unaccountable delays, ate at her and made her bitter. But if Sarah’s impatience was coming to a head, Chaska’s situation was far worse. All of his options now were miserable. By protecting Sarah he had made enemies; by not joining the friendly camp he had made enemies; by not going with Little Crow he had made enemies; by being Dakota he had made enemies. Still convinced that his greatest danger was that Little Crow would return to attack the friendly camp, he crossed the grassy space again and brought Sarah and her children back to his tent, as all of the Dakota dug new entrenchments.

The next day, September 26, Sibley’s army finally appeared along a ridge to their north, between their tepees and the river. All morning Sarah could see them arriving in the distance, and all morning they did not approach but instead deployed howitzers and sent detachments to encircle the Dakota camps. A small group of mixed-bloods in the friendly camp did not wait, crossing over to the white soldiers’ camp with a flag of truce, according to Sibley’s written instructions, asking for conditions under which they could hand over the captives with their own safety assured. As they did so, an argument broke out between Chaska and Sarah. During the long uneasy night he had decided to flee, and Sarah, hearing this, urged him to stay.

Chaska knew that he could not track down and rejoin Little Crow without being fired upon as an enemy, but it might be possible for him and his family to go to the plains on their own, to find a hospitable village of Sissetons or Wahpetons, or even to go farther west and find a home among a less familiar band or tribe. He might become a refugee, but he would not be a prisoner. “He said he felt as if they would kill all the Indians,” Sarah wrote, “but we told him if Sibley had promised to shake hands with all that remained and gave up their prisoners, he would do as he said.” In the end she succeeded in convincing Chaska to stay. And in the end Chaska made it clear that Sarah’s word, not Sibley’s, was all that stood in the way of his escape out onto the plains. “If I am killed,” he told her, “I will blame you for it.”

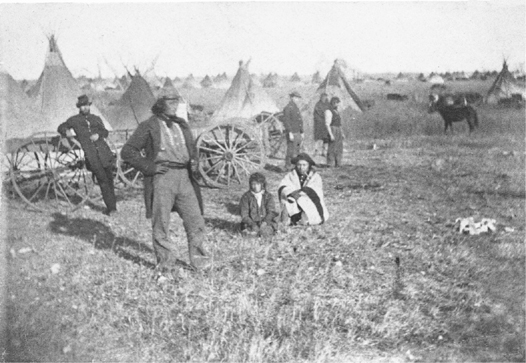

At noon, finally, a squad of Sibley’s men began to ride over to the Dakotas from the wide, treeless plateau, now filling with canvas tents, that someone had named Camp Release. The appearance of the blue-clad soldiers, bayonets flashing and flags aloft, accompanied by the sound of drum and fife, set off pandemonium. Samuel J. Brown described how “every man and woman in the camp, and every child old enough to toddle about, turned out with a flag of truce,” a surreal scene in which every piece of white cloth that could be found was attached to “every conceivable object” as the Dakota tried to dissuade the soldiers from opening fire. “One Indian who was boiling over with loyalty and love for the white man threw a white blanket on his black horse and tied a bit of white cloth to its tail,” Brown wrote, “and then that no possible doubt might be raised in his case he wrapped the American flag around his body and mounted the horse and sat upon him in full view of the troops as they passed by.”

Some of the remaining captives wept, some shouted or broke out laughing, and some simply collapsed. But Sarah’s mood was not joyful. “I felt feelings of anger enter my breast as I saw such an army,” she wrote, “for I felt that part at least might have come to our rescue before that late hour.” None of the Dakota knew from a distance what the soldiers intended, and Sibley’s display of strength failed to ease their anxiety. As Sarah wrote, “The Indians became much alarmed, and drew within their tepees. We were all eager to go to them immediately, but we were told we should remain where we were until Sibley came over.” A messenger crossed the short distance and announced that the white commander would follow a few hours later to speak with the remaining leaders of the Dakota.

While they waited for Sibley to enter their camp, Sarah ate the midday meal with Chaska and his mother, who seemed to bend under the weight of an evil premonition. The scene that followed was wrenching, one Sarah would remember for the rest of her life. Chaska’s mother ripped her shawl in half so that Sarah might have some warmth against the cool autumn air, while Chaska prepared to turn her over to the soldiers. According to Sarah, Chaska pleaded with her as a “good woman” to “talk good to your white people, or they will kill me; you know I am a good man, and did not shoot Mr. Gleason, and I saved your life. If I had been a bad man I would have gone with those bad chiefs.” Again she told him that he had nothing to fear, though other presentiments had been floating around the camp all morning. One mixed-blood witness recorded how the first group of soldiers to approach “repeatedly told us we were all to be executed and the insults of the soldiers who spoke the Indian tongue seemed a convincing act that all were to be put to death immediately.”

Sibley arrived in the midafternoon and ordered his men to form a hollow square, placing himself atop a wagon in the middle, surrounded by whites and Dakotas and tepees spread across a wide plateau for hundreds of feet in every direction. Speaking through an interpreter, he repeated his message of goodwill toward the leaders of the peace party and assured them that he would send men after Little Crow. In return, several of the friendly Indians spoke to condemn the war and, according to Sibley, to give him “assurance that they would not have dared to come and shake my hand if their own were stained with the blood of the whites.” Next, Chaska and other Dakotas, Lower and Upper, presented 91 white and 150 mixed-blood captives, bringing them forth as individuals or in small groups so that one of Sibley’s aides could write down their names. “After I was introduced to Sibley, Mr. Riggs, and others,” Sarah wrote, “they requested me to point out the Indian who had saved me. [Chaska] came forward as I called his name; and when I told them how kind he had been they shook hands with him, and made quite a hero of him, for a short time.” She was asked to leave the circle, apparently because Nellie was crying, and so she went inside a nearby tepee until the presentation of prisoners was finished and the time came for the white women to be taken away.

As they walked across the prairie to Camp Release, Sarah was full of frustration and fear for Chaska. Most of her fellow captives, though, were ecstatic at their release and ran across the open space, singing and shouting. Once inside Sibley’s camp, the women became the object of gawking; they were given constant attention and as much food as the men could find. The night was not so festive. The long, cold nights of a Minnesota autumn had taken hold, and lacking a stove in their tent or clothing beyond their summer dresses and the occasional shawl or thin blanket, they lit small fires for warmth, huddled together in family groups, and pressed their faces to the dirt to avoid the smoke. “I was a vast deal more comfortable with the Indians in every respect,” Sarah wrote, “than I was during my stay in that soldier’s camp, and was treated more respectfully by those savages, than I was by those in that camp.”

That same day, September 26, the Saint Paul Daily Press printed a momentous announcement under the headline THE PRESIDENT’S PROCLAMATION.

News of the great event of the war has reached the frontier. The President has issued a proclamation, declaring, that on the first day of January, in the year of our Lord one thousand eight hundred and sixty-three, all persons held as slaves within any State, or any designated part of a State, the people whereof shall be in rebellion against the United States, shall be thenceforward and forever free, and the executive government of the United States, including the military and naval authority thereof, will recognize and maintain the freedom of such persons, or any of them, in any efforts they may make for actual freedom.

Abolitionist editors rejoiced, but for most citizens of the Northwest another step toward the end of slavery was an abstract development that had little effect on their daily lives. What was not abstract was the question of what to do with the Dakota. Two weeks earlier, Governor Ramsey had addressed the state legislature and said that “the Sioux Indians of Minnesota must be exterminated or driven forever beyond the borders of the state.” With Sibley in possession of the captives and Little Crow far away, the process of activating both solutions would now begin.