John Pope’s messages were no less abrasive to his superiors in Washington than they were to Henry Sibley. From the start Lincoln and his military brain trust, War Secretary Edwin Stanton and General in Chief Henry Halleck, had known Pope was deeply unhappy, in spite of—or because of—the many obsequious and reassuring notes the exiled general had sent to Stanton. “I am sure you know that what I undertake I do with my whole heart,” Pope had written early in his stay in Minnesota. “No considerations of any kind will affect my action in the discharge of duty.” Running the Military Department of the Northwest with his “whole heart” seemed to mean, at least from Washington’s point of view, issuing an endless stream of requests that stood no chance of being granted. Five hundred wagons, 2,600 men on 2,600 horses, 5,000 paroled Union prisoners, two brigadier generals of Pope’s choice: all were denied to Pope, and Stanton had finally asked Halleck to “make some order defining the extent of operations to be carried on in the Northwest as an Indian campaign” and find a way to communicate that “whatever is sent to General Pope will leave a deficiency to the same extent in other branches of the service”—a polite way of reminding Pope that he was no longer the big man on the block.

In response, Pope painted a catastrophe in ever broader strokes. “You do not seem to be aware of the extent of the Indian outbreaks,” he wrote to Halleck, and then engaged in one of George McClellan’s favorite tactics, overstating his opposition by a factor of at least ten, describing Little Crow’s assembled forces as 2,600 mostly mounted warriors when the truth was that Sibley now reported 250 warriors “yet to be found and dealt with.” Even that number was an exaggeration, but a much lesser one: the Dakota leader now traveled with little more than a hundred fighting men, most of them on foot. Pope described the Dakota and Nebraska territories as entirely depopulated and wrote that the property of 50,000 people had been abandoned when the truth was perhaps a third of that number. Even more fantastically, he repeated the claim that the Ojibwe of northern Minnesota were on the “verge of outbreak” and somehow ascertained the plans of several dozen tribes between the Mississippi River and the Rockies, warning that “the whole of the Indian tribes as far as the mountains are in motion.”

Pope’s reports were consistently on the mark in only one respect: the fear and chaos the Dakota had caused in the settlements southwest of Saint Paul. “You have no idea of the wide, universal, and uncontrollable panic everywhere in this country,” he wrote, and to make his point, he described “children nailed alive to trees and houses, women violated and then disemboweled—everything that horrible ingenuity could devise.” Much of what had been reported to Pope via messengers and newspapers was, in fact, the product of “ingenuity,” but the truth was shocking enough. Over three hundred settlers were dead, many of them women and children, with hundreds of others still unaccounted for, a toll on whites exceeding that of any other Indian war in American history. Even with the threadbare economic status of many frontier farmers, the monetary losses in terms of built structures, livestock, and farm implements ran into the millions of dollars. The worst of the violence in the settlements was committed by a few hundred men at most, but they had ranged widely and at great speed, striking hard from the Iowa border up to the Big Woods. Editors vied to pass along the most lurid atrocities, almost none of which were based on firsthand reports and many of which were simply escalated retellings of a few killing scenes, but Pope made little effort to determine the truth of the situation. He seemed to revel in painting a whirlwind he could barely control.

The truth of Pope’s own situation, though, was that the timing of his appointment to the Northwest had left him with little to do. By the time his letters began to reach Sibley in the Upper Minnesota River Valley, the whirlwind was all but spent. Killings in the settlements had become sporadic and far between, and all of the shooting between soldiers and warriors had stopped, aside from the final battle at Wood Lake, which, in any event, Sibley directed on his own. Great unrealizable plans and unattainable requests aside, Pope’s role as the trials began was to relieve Sibley of the responsibility for the ultimate dispensation of the Dakota, both those sentenced to death and those with no place left to go. And even that role began to recede in importance once Sibley was finally notified of his promotion to a Union generalship on October 6 and the last of the stragglers from Little Crow’s breakaway party had begun to return to Camp Release and the Upper Agency.

Pope’s messages to Henry Halleck, at first fairly dry and factual, soon became inaccurate, exaggerated digests of Sibley’s to him. “The Sioux war may be considered at an end,” he wrote in the late hours of October 9. “We have about 1,500 prisoners—men, women, and children—and many are coming every day to deliver themselves up. Many are being tried by military commission for being connected to the late horrible outrages, and will be executed.” Anyone with a legal background—and Lincoln, Stanton, and Halleck all qualified—might have raised an eyebrow or two at the assumption that all of the trials would end in death sentences. At three the next afternoon, Pope sent another odd, rushed telegram to Halleck using much the same language.

The Sioux war is at an end. All of the bands engaged in the late outrages, except 5 men, have been captured. It will be necessary to execute many of them. The settlers can all return. I have not yet heard from the expedition to the Yankton villages, but with the return of that there will not be a hostile Indian east of the Missouri. The example of hanging many of the perpetrators of the late outrages is necessary and will have a crushing effect. I shall tomorrow issue an address requesting all the frontier settlers to return to their homes.

Pope’s claim that all but five of the hostile Dakota had been captured was nonsense: as was fairly well known, Little Crow was traveling west with a hundred or more warriors and was still well short of the Missouri River. The “expedition to the Yankton villages” referred only to a small detachment of men trying to follow Little Crow’s movements, but Pope began to describe an imminent battle of epic proportions in the Dakota Territory between Sibley’s forces and thousands of Dakota warriors, claiming to have “no fear of the results.” He also lacked a basic understanding of the “settlers” and their situations. Most of them were not prosperous farmers with hundreds of fertile acres and cash reserves; most were poor homesteaders, now left with only their oxen or horses, if that. Many were missing the heads of their households; many had seen or heard stories of their homes and barns being burned to the ground. While some were determined to reestablish their farms, many others were making plans to return to the states or even the countries from which they’d come, or planning to live with relatives in Minnesota and neighboring states for the indefinite future as they worked to piece together their shattered lives.

Finally, on October 13, for reasons lost to history, Pope’s rhetoric shifted. As he indicated in a midmorning telegram to Halleck, “There is strong testimony that white men led the Indians in late outrages. Do I need further authority to execute Indians condemned by military commission?” For the first time since accepting his generalship in the Union army a year earlier, he began to question the limits of his executive authority. Perhaps a lost communication from Stanton or Halleck checked him. Perhaps some hint in one of Sibley’s long letters jarred him into an understanding of the immense responsibility attached to summary executions. Perhaps he was simply protecting himself from future executive censure. Or perhaps he was influenced by information originating with the Indian agent Thomas Galbraith, who would write his own report later in the fall suggesting that traders, largely Democrats with no love for the Republicans now running the state and the country, had intentionally agitated the Dakota.

Pope would soon drop this last possibility altogether, but in questioning his authority to order executions he was finally acting judiciously. For fifty-five years, until the start of the Civil War, Article of War 65 had held sway in the matter of capital punishment via court-martial, providing that peacetime death sentences handed down by military courts required executive sanction. In writing new rules after Fort Sumter, Congress had stipulated that the president must confirm “any sentence of death, except in the cases of persons convicted in time of war of murder, rape, mutiny, desertion, or as spies.” Then, in July 1862, Congress reversed course and stipulated that commanding officers could declare punishments but that “the judgment of every court-martial shall be authenticated by the signature of the President.” Precedent from other conflicts with Indian tribes was murky and inconsistent, so by putting the cases in front of a military commission Pope and Sibley had at the very least left themselves subject to review by the executive branch. In any case, it would have been strange indeed for any high-ranking officer, but especially an experienced Union general, to assume that death sentences handed down by a military commission should not be reported to the president.

In a cabinet meeting the next day, October 14, Edwin Stanton read Pope’s latest dispatch from the frontier out loud; this was probably the second of the two telegrams announcing that the war had ended and that he “was anxious to execute a number” of Dakotas. That night, Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles used his diary to record a personal opinion shared by many of the men in the room. “I was disgusted with the tone and opinions of the dispatch. It was not the production of a good man or a great one. The Indian outrages have, I doubt not, been great—what may have been the provocation we are not told.” Just one month earlier, Lincoln had listened to Whipple’s accounting of the “provocations” at the heart of the Dakota War, and it is not a leap to read Welles’s words as a comment on Pope’s total lack of interest in those causes.

No other documentary record of the cabinet meeting exists, but it is clear that the oral recitation of Pope’s dispatch was a key moment in the story of the Dakota War. Lincoln found Pope’s drumbeat for executions as dissonant as did Welles, and soon after conferring with his department heads, he made his decision. At 2:15 that same afternoon, Stanton sent a wire to Pope indicating that the cabinet meeting had taken place and that the president had instructed him “to say that he desires you to employ your force in such manner as shall maintain the peace and secure the white inhabitants from Indian aggressions, and that upon the questions of policy presented by you his instructions will be given as soon as he shall obtain information from the Indian Department which he desires.”

Three days later, on October 17, Lincoln halted the pell-mell rush for vengeance. The key document has not survived, but as Pope reported to Sibley, “the President directs that no executions be made without his sanction.” The outcome of the Dakota War trials would be adjudicated in Washington, D.C., not in Saint Paul. Pope’s “questions of policy” were probably limited to the requirement for executive review, but Lincoln was equally interested in the legal criteria applied by the military commission and the fairness of the trials, as well as the moral and political costs of hanging hundreds of men on potentially rickety convictions. As high as the stakes were, though, this was comfortable territory for the president, whose nose for the law had been honed by eleven busy years on the Illinois circuit. He had been asked a set of very specific legal questions and would rule on those questions. Any compassion he felt for the Dakota prisoners was subsumed in his larger sense that justice might not have proceeded—or be proceeding—according to legitimate legal standards, a sense that had grown out of his deep distrust of Pope’s manner and motives. In this way, and entirely ironically, Pope himself probably was as influential as anyone in bringing about Lincoln’s willingness to intervene.

The word that executions had been placed on hold by the president would soon spread through Saint Paul, the state of Minnesota, and all of the Northwest with lightning speed and thunderous results. In New York, on the same day Lincoln put a halt to immediate executions, the convention of Episcopal bishops ended on a plaintive note. “To hate rebellion, so uncaused, is duty; but to hate those engaged in it was the opposite of duty,” said Bishop McIlvaine of Ohio, who closed the proceedings with a prayer that “the nation and the Church might soon be united in the bonds of peace and fellowship.” Before leaving the city, Whipple secured the signatures of all twenty bishops present on an “Indian statement” he hoped would prod Lincoln further on the questions he’d raised during his visit in September. In Washington and back in Minnesota, that visit had attracted notice. U.S. representative Cyrus Aldrich, reported the St. Cloud Democrat, was “knocked down” in a Saint Paul saloon by a former member of the First Minnesota regiment for mocking Whipple and calling him a “secessionist.”

One set of battles, white against Indian, was finished for the time being. Little Crow was somewhere to the west, the threat of his return diminishing as winter came on fast. But another set of battles, white against white, was just beginning.

After six weeks of trials, the final sentence of death given to the final Dakota prisoner was announced on November 5 at the Lower Agency, inside one of the only structures still intact, a squat, square wooden building that had once served as trader François LaBathe’s summer kitchen. The tally: in fewer than thirty days spread across six weeks, 392 trials had been held, resulting in 303 sentences of death, 16 sentences of imprisonment, and 69 acquittals. The first twenty-nine trials at Camp Release, which required eight or nine days over two weeks, had at least followed the basic outline and evidentiary standards of a proper military court-martial. Then, on October 15, the pace had quickened dramatically as the commission did away with such trappings of the law as arraignments, pleas, and detailed specification of charges; now it embraced John Pope’s cavalier mandate that “any sort of complicity” in the war was grounds for capital punishment. After the move to the Lower Agency, the process was further hastened to an absurd degree: most of the trials took less than ten minutes, and prisoners were sometimes brought forward in groups of six or eight, chained at the ankles.

During this last phase of the trials, in fact, a Dakota warrior was likely to be sentenced to death simply because he could not produce a witness to vouch for his conduct. The speed of the trials after October 15 was abetted by a set of simple ground rules that seemed to have no single author, though they were all guided by Pope and implemented by Sibley. None of the short war’s battles—not the ambush at the Lower Agency, nor the battles at New Ulm, Birch Coulee, and Wood Lake—would be defined as an action between equal adversaries acting in a military capacity. Rather, they were to be considered capital crimes, unprovoked aggressions akin to the killings in the settlements.

Thus there was no need to ascertain which of the Dakota had visited the farms and dirt lanes along the river valley and the settlements to the north and south, bringing death to hundreds of white men, women, and children. Now, any prisoner proved to have “fired in the battles, or brought ammunition, or acted as commissary in supplying provisions to the combatants” was as deserving of a death penalty as someone who set fire to a farmhouse with a white family inside. Most crucially, the prisoners, all of whom had by this point heard Sibley’s promise to punish only “murderers,” were not told of this, and so may have willingly admitted firing shots at the battles of New Ulm, Birch Coulee, or Wood Lake. The ex-slave and adopted Dakota Joseph Godfrey became a kind of informal prosecutor, a role decidedly outside the bounds of a proper court-martial, not only offering evidence but dramatically cross-examining defendants, probably out of eagerness to reduce his own sentence. The information collected from the mixed-bloods and friendly Indians by the Reverend Stephen R. Riggs became ever more essential, even when it was as simple as a statement that a defendant had been seen leaving camp with a group of armed warriors in the hours before a battle. By defining the overall conflict as a war, justifying General Sibley’s jurisdiction in the first place, but calling any participation in that war a capital crime, the trials allowed his commission to deliver ever more rapid summary judgments, subject to no appeal, on all of the Dakota who shuffled in and out of the tented courtroom.

Within months, an argument about the propriety and legality of Sibley’s commission and Pope’s standards of guilt would begin, an argument that still remains unsettled 150 years later, but out on the prairie there was no way for the Dakota to lodge a protest and no white person willing or able to stand up and slow down the process. The shift to a far more streamlined format allowed the commission to hear and decide on more than 250 cases over the last ten days of trials. No sentence was ever read out loud to the defendant, and this created great confusion among the Dakota. Some prisoners seemed to assume that the government was waiting to execute all of the arrested men together and that no one had really been acquitted; others seemed to think that the fact they had not been taken to a gallows or separated from the other prisoners immediately following their trials meant that they had been found innocent. But for all of them, the uncertainty kept them on edge and filled the camp with fear.

What was gained by conducting trials that would take anywhere from a few minutes to an hour each to decide the fates of the Dakota men rounded up on the prairie? Not justice, at least not in the legal sense of the word. And not satisfaction; as far as most of the settlers and many of the soldiers were concerned, such jurisprudence, hurried as it was, was unnecessary. “I am for shooting down the cowards as fast as they approach the camps,” wrote one private, a sentiment that would continue to grow all autumn and into the winter, which crept ever closer as the prairie grasses began to frost overnight and the tents seemed made of thinner and thinner cloth.

During the latter phases of the trials, a judgment of another sort was being issued, one that said that any armed resistance to white encroachment was worthy of death. No military commission had ever before been used to try enemy combatants for firing shots on a battlefield. To set a standard that equated all acts of Dakota violence and all perpetrators, erasing distinctions between acts against civilians and acts against soldiers, was to suggest that no true conflict between the whites and the Dakota as peoples could exist. And to suggest that no true conflict existed was to suggest that every act of Dakota violence, including the pulling of a trigger in the face of firing white soldiers, was the result of cultural deficiencies and racial wickedness.

Not every white person was happy with the proceedings. After the trials were complete, John P. Williamson, son of the missionary Thomas S. Williamson, would write to his mission board in frustration and despair.

400 have been tried in less time than is generally taken in our courts with the trial of a single murderer. Again in very many of the cases a man’s own testimony is the only evidence against him. He is first prejudiced guilty of any charge any of the Court choose to prefer against him and then if he denied he is cross examined with all the ingenuity of a modern lawyer to see if he cannot be detected in some error of statement. Then they are not allowed any counsel. They are scarcely allowed a word of explanation themselves, and knowing nothing of the manner of conducting trials if a mistake occurs they are unable to correct it. And often not understanding the English language in which the trial is conducted, they very imperfectly understand the evidence upon which they are convicted.

Now that there would be no more Indian-chasing, the soldiers’ minds turned back to the reason they’d enlisted in the first place. While the trials continued at the Lower Agency, Sibley’s companies filled the empty level spaces with drills and more drills in anticipation of boarding the riverboats and trains that would finally bring them face-to-face with the rebellious “secesh.” Guards made the rounds three times a night, while other soldiers combed the settlements on burial duty, still coming upon human remains from attacks that had occurred almost two months earlier. The men had split into two loose divisions, one a faction who saw their duty to protect the Dakota as part of the lawful preparation for proper executions and the other, smaller but very vocal, who saw the opportunity for mischief or individual revenge.

Since arriving at the Lower Agency to continue the trials, the soldiers had been calling their latest home Camp Sibley, but Sibley himself refused to use the term and continued to issue orders designed to keep his men away from the Dakota tepees. On October 22, he had confided to his wife, “I find the greatest difficulty in keeping the men from the Indian women when the camps are close together. I have a strong line of sentinels entirely around my camp to keep every officer and soldier from going out without my permission; but some way or other, a few of the soldiers manage to get among the gals.” He also issued orders against taking buffalo robes from their prisoners or trading whiskey for goods and favors. For the Dakota—the innocent and the condemned—such actions were humiliation; for the soldiers involved, they were sport; for their more conscientious bunkmates and senior officers, they were a constant threat to the integrity of the command.

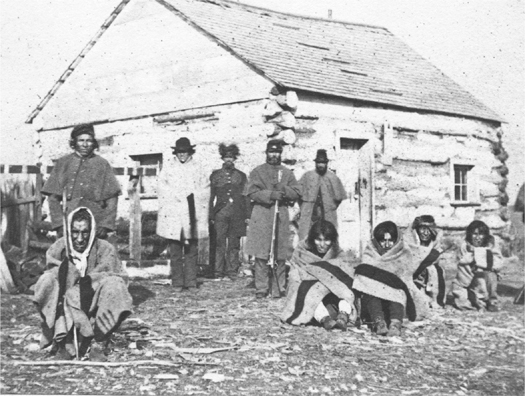

With all of the trials complete, Sibley ordered the implementation of Pope’s newest plan, to send the convicted prisoners downriver to the regional hub of Mankato while herding the women, children, elderly, and innocent straight overland to Fort Snelling, where they would be held until the Office of Indian Affairs could decide on their final destination. Lieutenant Colonel William Marshall of the Seventh Minnesota, a banker, farmer, newspaperman, staunch Republican, and member of Sibley’s trial commission, was charged with preparing 1,700 innocent Dakotas and all of their property for the trip. Aware that civilians and militia alike might be inclined to set upon the train as it traveled over the prairie, Marshall delivered a public notice to a reporter for publication in the Saint Paul Daily Press: “I would risk my life for the protection of these helpless beings, and would feel everlastingly disgraced if any evil befell them while in my charge. Through the PRESS, I want the settlers in the valley, on the route we pass, to know that they are not the guilty Indians (some 300 of whom are to be executed at South Bend) but friendly Indians, women and children.”

As it turned out, Marshall was not the only soldier talking to the papers. One week later, a letter to the editor written by trial recorder Isaac Heard appeared in the Saint Paul Pioneer, datelined “from Gen. Sibley’s camp” and bearing no name. “When this outrage broke out the Indians thought they would winter their squaws near St. Paul,” Heard wrote. “Their statements will prove true, but the fact will not be as agreeable to them as they supposed.”

On the morning of November 6, Sibley watched as Marshall’s overstuffed train crept away down the ferry road to the river crossing where Captain Marsh and his men had been ambushed on the first day of the fighting. With the families rode Marshall, the Indian agent Thomas Galbraith, the missionaries Samuel Hinman and John P. Williamson, several mixed-blood translators, and the leaders of the peace party, including Paul Mazakutemani. For whites, the journey was aimed at “housing” the Dakota noncombatants, a movement east before the inevitable move west onto some as-yet-undecided distant reservation. For the Dakota, the journey was filled only with dread and despair. For twenty-five years they had been subject to the Interior Department’s fatally flawed process of treaty-making, but this was pure Jacksonian removal, the first step of a forced exodus from their last remaining lands, a dispossession that went far beyond a “relocation,” a march with no ultimate destination that threatened them with death both figurative and literal.

Before dawn on November 8, back at the Lower Agency, Sibley’s soldiers rose to prepare the condemned prisoners, who were placed into thirty wagons, ten to a wagon, facing each other in chained pairs with covered heads. They departed at the perfect rise of an early-winter sun, Sibley and his staff leading two regiments of infantry, behind which were the supply wagons pulled by mules and the artillery bringing up the rear. The Dakota women accompanying the train as laundresses or cooks were forced to walk. The first day took Sibley and his charges down the government road on the south side of the Minnesota River, with Fort Ridgely visible all the while on its high ridge across the valley. That night Sibley made camp across the road from a farm occupied by John Massopust, a young man who had lost his father, his two sisters, and his six-year-old cousin in the first wave of killings in August. Here, apparently, Sibley sent a courier riding off to John Pope in Saint Paul with the final list of 303 condemned prisoners under his signature.

The next day, a Sunday, the procession of prisoners again headed south toward New Ulm. This route may have been chosen in order to accommodate all of the walkers, wagons, and horses of Sibley’s train, but it was provocative in the extreme. Residents and relatives were still burying bodies and cleaning up the town. Approaching the point where prairie gave way to the town’s first buildings, Sibley was intercepted by two men, one the county sheriff and the other a twenty-one-year-old named Frederick Brandt, whose military dress and claim to be a major in the state militia struck Sibley as silly. Brandt stepped forward to hand the general a letter and watched as he read: “As I am told you intend to move your Indian prisoners through the town of New Ulm, I declare this an insult, and the people will resist—we are just today burying the dead, which was shot in the last engagement with the Indians and therefore better to move your prisoners out of the sight of New Ulm we don’t want to be interrupted by anyone.”

The letter also demanded that Sibley turn over any of the condemned Dakotas who had been implicated in either of the two attacks on New Ulm. The general was not about to release any of his prisoners to the local sheriff and his sidekick, but he did agree to move his convoy past the town via the more difficult route on its southern side, edging slowly along the top of the bluff above. On his guard now, Sibley deployed one company of about eighty men on each side of the wagon train with ball cartridges loaded in their rifles. As they passed directly above the town, they came upon a cluster of townspeople of both genders and all ages blocking the road and carrying “all conceivable weapons,” including clubs, knives, stones, guns of all types, pitchforks, scythes, brooms, “aprons full of brickbats,” and, according to one report, “the proverbial kettle of hot water.” One of Sibley’s soldiers wrote that “the first I knew, one very large German woman slipped through in front of me, and hit one of the Indians on the head with a large stone. Well, he fell backwards out of the wagon, he being shackled to another Indian that held him, so he was dragged about five rods.”

The fusillade ended only after Sibley took up a rifle himself and led some of his men in a demonstration charge, bayonets forward, to scatter the attackers; he wrote later that “the presence of the women and children alone saved the male actors in this attack from being punished as they deserved by the fire of my forces.” Brandt, the young man who had met him just outside of town, was arrested, along with forty or so other men. Brandt’s claim that he had worked in his “utmost endeavor to prevent the attack” and his demand that the men be released to go back to burial duty met with the wrath of Sibley, who refused to comply. Sibley also sent a letter off to Governor Ramsey expressing his belief that Brandt was only claiming to be an officer in the militia, expecting that the governor, as commander in chief of the state’s forces, would take some separate punitive action of his own.

That night, finally, they stopped a few miles short of Mankato, the injured Dakota riding in ambulance wagons. Work began on a wooden shed to house the prisoners, and the arrested attackers from New Ulm were set free to head back home. The spot, just west of the sharp elbow where the Minnesota River turned to the north after its 150-mile course southward from the border of the Dakota Territory, would be their home until Pope sent along directions for the executions. Someone called it Camp Lincoln, and the name stuck.

Over the previous two days, meanwhile, Sibley’s message to Pope had become Pope’s message to Lincoln, listing the names of the 303 Dakota sentenced to death. The president’s immediate response arrived in Saint Paul by telegram on November 10 just about the same time that the condemned men were being hoisted off the wagons two by two, still paired up by their chained feet.

Your dispatch giving the names of 300 Indians condemned to death is received. Please forward as soon as possible the full and complete record of their convictions; and if the record does not fully indicate the more guilty and influential of the culprits, please have a careful statement made on these points and forwarded to me. Send all by mail.

To Abraham Lincoln the law was sacrosanct, the first religion he’d ever found, and all his life he was as sensitive to bad lawyers as a priest might be to false prophets. Now he was engaged as a lawyer, with the understanding that these sentences must become his responsibility, especially in the absence of a trustworthy and authoritative voice from the frontier. He would, over the next few weeks, become the first and only president ever to consider three hundred death sentences all at once. Later Lincoln would tell Congress that he began his review “anxious to not act with so much clemency as to encourage another outbreak on one hand, nor with so much severity as to be real cruelty on the other,” firm as ever in his belief that while punishment would be necessary, punishment that failed to fit the crime was no justice at all.

The news of Lincoln’s message spread through the halls of power in Saint Paul and out onto the streets of the city. Within hours, or perhaps even minutes, Pope had passed the message along to Ramsey, and from Ramsey it went to the newspapers and to many of the city’s leading citizens. Both men began to compose their reactions, but Ramsey’s, predictably the shorter, made it to the White House first. “I hope the execution of every Sioux Indian condemned by the military court will be at once ordered,” the governor wrote. “It would be wrong upon principle and policy to refuse this. Private revenge would on all this border take the place of official judgment on these Indians.”

Lincoln referred Ramsey’s message to War Secretary Edwin Stanton, but not for any decision on the death sentences. He had a great deal to consider over the next three weeks, and he was not going to let himself be rushed into ordering anything “at once.”

All day long on November 6 the train of Dakota families crossed the Minnesota River at the Lower Agency; the more than fifteen hundred people, with their wagons, mules, and horses, required dozens of ferry trips. The next morning Lieutenant Colonel Marshall led them up to the crest of the valley wall, across the prairie and past Fort Ridgely as they moved toward their winter quarters at Fort Snelling. With so many women, children, and elderly in the group, progress was slow. Not until November 10 did they approach the river town of Henderson, after which they would turn north toward Saint Paul. It was towns like Henderson—and Saint Peter a few miles away—that had received the greatest influx of wounded and distraught settlers during the first few days of the war, and their memories were still fresh. As it turned out, the families’ ride through Henderson was as dangerous as the prisoners’ had been around New Ulm. “We found the streets crowded with an angry and excited population, cursing, shouting and crying,” Samuel J. Brown wrote.

Men, women, and children, armed with guns, knives, clubs, and stones, rushed upon the Indians as the train was passing by and, before the soldiers could interfere and stop them, succeeded in pulling many of the old men and women, and even children, from the wagon by the hair of the head and beating them, and otherwise inflicting injury upon the helpless and miserable creatures.

One white woman took a nursing baby out of its mother’s arms and slammed it into the ground before she was pulled away by some of Marshall’s men, leaving the infant motionless and close to death. Like Sibley, Marshall had to take a personal hand in driving off the attackers, riding up to one armed townsperson and using his sword to knock the man’s raised rifle away.

The procession finished moving out of the town and then stopped at a small patch of prairie by the river in order to make camp for the night. As Marshall dispatched scouting parties to find and intercept other settlers bent on violence, the Dakota went about the burial of the battered child, who had died shortly after the attack in town. The baby was “quietly laid away in the crotch of a tree” a little ways downriver in a ceremony Brown described as “perhaps the last of its kind within the limits of Minnesota; that is, the last Sioux Indian ‘buried’ according to one of the oldest and most cherished customs of the tribe.”

Finally, on the afternoon of November 13, the Dakota families arrived at Fort Snelling. The procession stopped for one night on a rise south of the federal garrison, exposed to the full brunt of the winter winds, before Marshall moved them to the bottomlands at the confluence of the Minnesota and Mississippi rivers, with the southern wall of the fort looming one hundred feet over their heads. A soldier, Thomas Rice Stewart, described the sudden village next to the water.

There was something about it so weird, strange, and unnatural it seemed more like a dream than reality. The many and oddly constructed tepees, some made of reeds and rushes, others of skins of animals, etc. The many camp fires, smoke from which made a cloud which hung over the camp like a pall. The barking of dogs, of which there seemed to be a goodly number. The shrill voices of the squaws as they performed their various duties. All of this combined to make it a strange scene.

Concentrated in two makeshift camps, one for the prisoners at Camp Lincoln and one for the innocent at Fort Snelling, the Dakota waited on two judgments. The first was the final removal of the families, the question of where and when their exile might begin, a decision that lay in the hands of the Department of the Interior and the commissioner of Indian affairs. The other judgment now rested in the hands of Abraham Lincoln, the man many Dakotas, even now, called Great White Father. News had already begun to spread, among whites and Indians alike, that the president himself would decide who was to live and who was to die. This was true. But first, for three weeks, the wires from Washington would go quiet.