By Christmas Eve, the slashing winter weather of early December had given way to blue skies and unseasonably mild air, turning snowfall to slush and turning all roadways to mud, but still Mankato kept filling with people. Hundreds rode in, hour by hour, crowding into every available corner and cranny as they waited to witness the event of the century. Christmas on the northern prairies centered on private rituals: a fresh coat of paint for the walls, the careful construction of paper ornaments, tables laden with meats, sausages, home-brewed ale, dried apples, creamed porridge, breads and cakes. In these pioneer days, before a single church had been finished in town, religious observances usually happened at home, with a reading of the nativity scene and the singing of a few hymns and folk songs. But this year, all traditions were disrupted or placed on hold. The execution of thirty-nine Dakota Indians was set for ten o’clock on the morning after Christmas.

Perched just above the sharp, twisting bend where the Minnesota River made its turn toward Saint Paul, Mankato was the most common stopover between the state capital and the southwestern quarter of the state. Every guest chamber was full, or overfull, and so too were many of the private homes that had welcomed relatives or rented out beds. Those visitors too late to find lodgings had gone back downriver or across the prairie to towns close enough to allow them to make a short return ride on the 26th. Many camped in tents or slept in their wagons. More than a thousand soldiers were already present, charged with watching for signs of trouble. Eager spectators were staking claims on rooftops and balconies and windows, in the streets and up on the bluff overlooking town, on the sandbar in the river and even along the opposite shore. Only one criterion served to recommend a vantage point: an unobstructed view of the giant gallows nearing completion on a clear, grassy table of ground in the town’s lower plateau, between Front Street and the river landings.

Thirty miles apart, similar in layout and parallel in history, the settlements of New Ulm and Mankato were still so different that they serve as object lessons in two principal threads of American town-making. New Ulm exemplified the utopian urge in western settlement, the idea that an insular group of people could find a refuge away from the corrupting pressure of large cities in order to exercise whatever ideas of society, religion, or politics they held most dear. The Turnerians of New Ulm were, to many other settlers, an odd, suspicious bunch, often referred to as a “colony” and distrusted for rationalist views that disregarded the Sabbath and kept to a social calendar built around exercise sessions at the town’s Turnhalle, which also hosted plays, concerts, lectures, and dancing exhibitions. For more than a few locals, looking in from the outside, the activities of the Turnerians seemed too separate for comfort, too removed from mainstream practices to be considered fully American.

Mankato modeled a different sort of freedom. The birth of Mankato, like that of most other Minnesota towns west of the Mississippi River, had been enabled by the treaties of 1851, which moved the Dakota off six million acres of tribal lands and placed them along the Minnesota River. With those treaties, tens of thousands of plots of dark, rich alluvial soil were made available for white homesteaders and speculators. In 1852, one year before the Chicago Land Company sent an exploratory party north to the New Ulm site, brothers-in-law Henry Jackson and Parsons King Johnson had ridden beside the Minnesota River to its southernmost point, where they found a Mdewakanton Dakota leader named Sleepy Eye who was willing to accept food and supplies in exchange for a place to rest and information about the landscape. According to the story Jackson and Johnson told, Chief Sleepy Eye guided them to a spot above the high-water mark just a few hundred yards east of the mouth of a tributary of the Minnesota River the Dakota called Makato Osa Watapa, or “the river where blue earth is gathered.” Less than six months later the brothers-in-law were in business as the Mankato Townsite Company, bringing people and supplies by steamboat to establish a foothold before other Indians or other white speculators could intervene.

If indeed Sleepy Eye recommended the spot, he had done well for Jackson and Johnson. Ideally situated a full day’s stagecoach ride away from Saint Paul and usually open to steamboats two or three weeks longer than New Ulm, Mankato boomed. Within ten years, as the white population of Minnesota Territory rose from 10,000 people to over 100,000, Mankato grew to encompass a major steamboat landing, a log schoolhouse accommodating more than a hundred students, a nondenominational private school, and growing communities of Methodists, Baptists, Presbyterians, Episcopalians, and Catholics. The all-comers impulse put the town into competition with similar settlements along the river—Saint Peter, Shakopee, Henderson, Le Sueur—all of which were working without rest to attract more settlers, business dollars, and steamboat traffic. At the same time, the river valley citizens came to act and think as one community, bonded by family ties, social events, churches, and mercantile relationships. Those bonds were especially tight today; today more than any other day in their short history the whites thought of themselves as whites, as one people with one common purpose.

Crews of soldiers and carpenters would continue to work through the evening and all of Christmas Day to make the scaffold ready, but already the structure was transfixing, a towering instrument of death built so sturdily that it might, in the words of one reporter, “serve well for future occasions of a like character.” Twenty-four feet square, it was wider than many of the town’s houses. Built to accommodate forty nooses, ten to a side, the entire structure was supported by eight equally spaced oak posts fourteen feet high and a foot square. Each of the top rails was notched ten times on its outer edge so that ropes could be draped over and fastened tight without fear of fraying and snapping under the weight of the condemned men. The giant platform on which the thirty-nine prisoners would stand was built so that it could drop straight down underneath the prisoners, as one piece, at the cutting of a central rope.

Even at this unheard-of scale, though, some expressed disappointment with its dimensions. A reporter for the Saint Paul Press lamented that the apparatus could have been much larger “had the President been less squeamish, and even then justice would have been defrauded of its dues.” The hanging, originally scheduled for the 19th, had been postponed for one week due in part to Colonel Miller’s inability to find four hundred feet of properly thick rope in town. Residents and visitors wandered by and stopped to watch the work in progress, chatting with the soldiers and marveling at the size of the structure. One man asked to be allowed to drive a single nail “in a place where it would be of service.” Handed a hammer, “the man drove the nail home, into a plank of the platform, thanked the soldier, said he was satisfied, and left.”

Closer to the river and in full view of the gallows stood a heavily guarded wooden enclosure containing the 264 Dakotas whose sentences had been stayed by the president, men whom whites despised all the more for being allowed to live. Many white observers reported their satisfaction that the gaps between logs in the prison wall were wide enough to allow an edifying view of the event. Meanwhile, “the thirty-nine,” as most whites now called those Dakotas selected by Lincoln for death, had been separated from their fellow prisoners and moved to the back room on the ground floor of a three-story stone warehouse adjacent to the stockade, whose waterside door faced the scaffold across a small lawn. Whispering spectators watched various men and women enter and leave the building—soldiers, clergy, and reporters, as well as wives and sisters bearing food—and surely they imagined the scene inside. At ten o’clock on the morning after Christmas, the condemned would emerge to mount the scaffold and then, in the words of one newspaper, “the slash of a sword, or the stroke of an axe, upon [the] rope, will drop the platform, and launch 39 horrible murderers into Eternity.”

On Monday, two days before Christmas Eve, several of the town’s leading citizens had approached Colonel Miller to request that the armed men filling Mankato be put to use keeping order and squelching dark plans of “private revenge.” Rumors moving along the river valley suggested that secret societies were forming. The governor was still writing to Pope and Lincoln about the threat of “designing combinations” of men and women. And without a doubt some of the whispers were true: in back rooms and private parlors, in barns and even in sheriffs’ offices, conspiratorial ideas were being voiced, violent possibilities raised. During this Christmas week, members of some of those impromptu groups were surely in town, measuring their courage as they eyed the fenced enclosure holding the reprieved men. The most dire scenario in the eyes of Mankatoans was that of a drunken mob attacking the jail or, even worse, rushing the scaffold before the platform dropped. Colonel Miller, whose chief strength seemed to be that he took all possibilities seriously, issued his twenty-first general order, a seven-part declaration built around item number four, which decreed that “the sale, tender, gift or use of all intoxicating liquors … by soldiers, sojourners, or citizens, is entirely prohibited until Saturday evening, the 27th instant, at eleven o’clock.”

If Miller had his way—and more than a thousand armed men all but guaranteed he would—no one would be drunk the night before the executions, the morning of the executions, or the evening after the executions. The occasion would be sober, without lubricant beforehand or revelry afterwards, and it would not be hijacked by out-of-towners with their jealous designs.

As the level of expectation rose along with the gallows, a much more private set of scenes unfolded in the unadorned ground-floor warehouse room where the thirty-nine waited, ankle irons chained to the floor, as the hour of their doom crept closer. A few were dressed in trousers and collared shirts, but most wore leggings and draped blankets over their shoulders. They had known of their ultimate fate only since Monday, when a company of soldiers had entered their log stockade at the heels of former Indian agent Joseph R. Brown, who gathered the 303 convicted men together to read out thirty-nine names. After answering, some with a grunt and some by saying “Ho,” each man was told to step forward so that he could be separated from his partner in chains.

At least one of the men who stepped forward, however, had done so as the result of an entirely preventable mistake. When Brown read out “Chas-kay-don,” he should have been presented with a reason to take special care. At least three men of the 303 in the enclosure, and probably more, answered to the name “Chaska,” which simply means “firstborn, if a male” in Dakota, and the three known examples present on that fateful day were in very different straits. Only one, Chaskaydon, was on the “black list,” condemned for killing and cutting open a pregnant woman in the settlements. Another Chaska, a Christian Dakota who also called himself Robert Hopkins and had been convicted of taking part in several battles, but not of murder or rape, had been singled out in a note from President Lincoln, following direct appeals from the missionaries Samuel R. Riggs and Thomas Williamson, vouching for his character and pointing out his efforts to save whites in the first days of the war.

The third Chaska, Sarah Wakefield’s protector, was also not on the list of the thirty-nine forwarded from Washington. But when the men were removed to their final prison room next door, there he was, marked for death, while the condemned Chaskaydon remained behind, with no inkling as yet of what a momentous turn his life had taken. No record exists to answer a set of crucial questions: Did Brown, or another officer, call out the name, after which Chaska stepped forward? Or did someone point at Chaska? Is it possible that he momentarily assumed that he was being separated out for further questioning or even to be set free? The question is unanswerable; in any case, Chaska did step forward. In that single awful moment his fate was sealed, though still he did not know it.

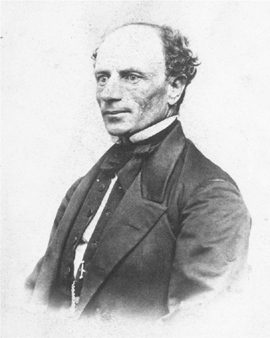

The soldiers who escorted the thirty-nine men out of their fenced enclosure began to taunt them, apparently against orders, saying that they were to be executed. Some of the soldiers had been doing this kind of thing for weeks now, ever since the formation of Camp Release, but Chaska and his companions knew they had reason to pay special attention. After they were moved into the warehouse, they were made to wait until midafternoon, when Colonel Miller and several of the men on his staff arrived with a small group of townspeople in tow. With them was the Presbyterian minister Stephen R. Riggs, the man who had collected much of the evidence against them. Colonel Miller read from a paper to Riggs so that the missionary could translate.

Tell these thirty-nine condemned men that the commanding officer of this place has called to speak to them upon a very serious subject. Their great Father at Washington, after carefully reading what the witnesses testified to in their several trials, has come to the conclusion that they have each been guilty of wantonly and wickedly murdering his white children. And for this reason he has directed that they each be hanged by the neck until they are dead, on next Friday, and that order will be carried into effect on that day, at ten o’clock in the forenoon.

This was the first official reading of their sentence, the first moment since their arrests north of the Upper Agency that any of the Dakota knew for certain they had been marked for death. Most of the men, it was reported, received the news “very coolly.” Miller had more to say. The prisoners were sinners whose only hope of redemption was through God, and as such each prisoner was “privileged to designate the minister of his choice,” which in the translation may have come across as a requirement as much as an offer. It is unclear if any of the prisoners chose, or were allowed to choose, to have no spiritual adviser. Twenty-four of the condemned chose Father Augustin Ravoux, now fifty-seven, who had come to the Minnesota Territory from France twenty-one years earlier to become the only Catholic priest among the Dakota. Riggs apparently removed himself from consideration, so twelve more were attached to Thomas S. Williamson. These clergy, plus at least three newspaper reporters, two from the Mankato papers and one from Saint Paul, would become constant presences in the room during the week, along with the soldiers guarding them and the women, often kin, who prepared their food.

On Tuesday morning, the day after their separation from the other condemned men, Riggs had returned to their cell to collect statements that were widely published as “confessions,” a term probably used in a religious sense. A few of the men were demonstrative, imploring Riggs’s help, but, he wrote, they “were immediately checked by the others, and told that they were all dead men and there was no reason they should not tell the truth.” “The truth,” as it turned out, wore thirty-nine different guises and in every case contradicted the testimony of Joseph Godfrey and the witnesses collected by Riggs and the members of Sibley’s military commission. Some of the stories seemed too convenient to be believed, while others displayed logic that was more difficult to disregard. One prisoner said that his only crime was to resist the release of the captives to the peace party of Dakotas. One said that he had fired only at whites who were already dead. One said he had armed to fight Ojibwes, not whites. One pointed out that “if he believed he had killed a white man he would have fled with Little Crow.” Some complained about the unfairness of the trials and the lack of representation, and many blamed Little Crow or other leaders for forcing or coercing them into fighting.

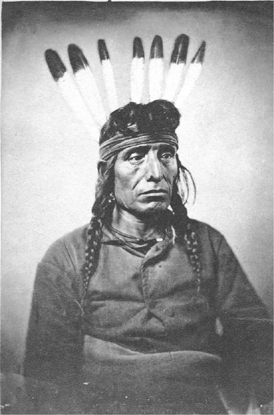

White Dog, the man who had met Captain Marsh at the ferry and called the soldiers across the river before many of them were shot dead, complained “bitterly that he did not have a chance to tell the things as they were; that he could not have an opportunity of rebutting the false testimony brought against him.” He added that he and his Dakota brethren “have done great wrongs to the white people, and do not refuse to die, but they think it hard that they did not have a fairer trial. They want the President to know this.”

One older man named Tatemina, or Round Wind, who had been Little Crow’s camp crier and was described by Riggs as “the only one of the thirty-nine who has been at all in the habit of attending Protestant worship,” told his interrogator that “he was condemned on the testimony of two German boys, who said they saw him kill their mother. The old man denies the charge—says he was not across the river at that time.” Some dictated messages for Riggs to translate, others handed him letters they had written themselves. One prisoner, Thunder That Paints Itself Blue, who had been convicted of arguing to kill white captives, wrote a bitter note to his father-in-law, the village chief Wabasha.

You have deceived me. You told me that if we followed the advice of General Sibley, and give ourselves up to the whites, all would be well—no innocent man would be injured. I have not killed, wounded, or injured a white man, or any white persons. I have not participated in the plunder of their property; and yet today, I am set apart for execution and must die in a few days, while men who are guilty will remain in prison.

When it was Chaska’s turn, he told Riggs that though he had headed to the Lower Agency on the first day of the killings, he and Hapa were instead sent away to check on a report that a white man was on the road. “Then came along Mr. Gleason and Mrs. Wakefield,” Chaska continued. “His friend shot Mr. Gleason and he attempted to fire on him, but his gun did not go off. He saved Mrs. Wakefield and the children, and now he dies while she lives.”

This bitter defense was Chaska’s final recorded statement. His deeds and words, for most of his life unnoticed by whites, had now in one six-week span been remembered, recorded, and passed along by Sarah Wakefield, by the trial recorder Isaac Heard, and finally by the Reverend Stephen R. Riggs. Chaska could have, and might have, protested the misunderstanding that had put him in the cell, but this is unlikely; to beg for mercy was not the way of a Dakota warrior, and to argue for another man’s doom in order to save oneself was considered the act of a coward. The point, in any event, was moot, for Chaska was never told that Abraham Lincoln had lifted his sentence.

That night the prisoners sent a request to Colonel Miller that he allow them to perform an important ceremony, and at nine o’clock, just as darkness fell, the thirty-nine “extemporized a dance with a wild Indian song.” The guards, fearful that the condemned were creating a cover or somehow seeking to communicate with the men imprisoned outside, then took the final step of fastening their ankle irons to the floor so that their physical freedom, taken away in increments small and large for so long, was finally reduced to its practical minimum. It was in this state that the prisoners received their kin from among the reprieved men, who were allowed inside on Christmas Eve in twos and threes to say their final good-byes.

“Several of the prisoners were completely overcome during the leave taking, and were compelled to abandon conversation,” wrote one of the reporters, who noted that others “affected to disregard the dangers of their position, and laughed and joked apparently as unconcerned as if they were sitting around a camp fire in perfect freedom.”

Riggs wrote later that many of the men spoke messages to be passed along to wives and children at Fort Snelling, but they must have understood that those messages might never arrive. How would such words of comfort, advice, or courage travel? When and where would kin be reunited? It was clear to all of the Dakota now that a terrible dispersal had begun, one that had already rent individual villages and families into separate pockets seeking survival. Fifteen hundred Dakotas, mostly women, children, and the elderly, were being held in the camp at Fort Snelling; a few hundred were still with Little Crow, moving to the northwest; untold numbers had joined Sisseton and Wahpeton kin in whatever scattered movements those bands were making across the Dakota Territory; and the rest were here, in Mankato. Thirty-nine were slated to depart on a celestial path they expected would lead to the country of spirits, a land populated by their ancestors; the others knew only that the journeys to come would be long, arduous, and no less mysterious.

Ravoux and Williamson were behaving as any clergyman attached to any military unit in the Civil War would have acted. In this way, and perhaps only in this way, whites thought of Indians and themselves as mostly the same. If Union chaplains felt bound to aid mortally wounded slaves or Confederate soldiers, helping them to prepare for imminent death, so too did the Minnesota missionaries believe in their powerful obligation to send the Dakota off to a better place. Indeed, much ink would be devoted to reports of the successful conversions of the prisoners, but again the evidence of Riggs’s translations said otherwise.

Round Wind, the old camp crier, asked that his kin be informed that “I have every hope of going to the Great Spirit, where I shall always be happy.” Several of the prisoners expressed similar sentiments, but Round Wind’s words ring loudest in the record, because that night a most extraordinary scene occurred when Colonel Miller came to separate him from the others and return him to the log enclosure outside. Whether or not the other prisoners were told of the reason for his departure, Round Wind’s contention that he had been nowhere near the site of his supposed crimes had been vocally supported by the missionary Thomas S. Williamson, and earlier that day a telegram had arrived from the president granting his stay. Lincoln and his lawyers still seemed inclined to shrink the number of executions, provided that they could point to a reputable voice of supplication, so Round Wind’s final travels, wherever they might lead, would not begin yet. Thirty-nine were now thirty-eight.

At sunup on the morning after Christmas, the small party of reporters was allowed inside for the last time. Wrote one, “The doomed men wished it to be known among their friends, and particularly their wives and children, how cheerful and happy they all had died, exhibiting no fear of this dread event. To us it appeared not as an evidence of Christian faith, but a steadfast adherence to their heathen superstitions.” And indeed it became clear that, despite several baptisms and professions of faith, most of the thirty-eight would seek to meet death in the manner of Dakota warriors. When white soldiers followed the reporters into the makeshift cell, they found that most of the prisoners had painted their faces and were laughing off their fate, asking the troops what had taken them so long and why things weren’t moving along more quickly.

“All at once” they began a death song, “wonderfully exciting” to the whites, a deep, dissonant singing and chanting that would continue on and off for the next several hours as one by one their chains were stricken away and their arms pinioned, elbows tied behind and wrists in front. As the hour of their execution approached, White Dog said his last piece, again blaming Little Crow and the leaders of the Mdewakanton tiyotipi for dragging them into the war. Father Ravoux led them in a final prayer session, and the prisoners were fitted with long eyeless caps made of white muslin. For the Dakota this was an immense indignity, the sign of a bad death; they would meet their fate with heads hooded, in the dark. “Chains and cords had not moved them,” wrote one reporter, “but this covering of the head with a white cap was humiliating.”

Just before ten o’clock all of their irons were knocked off and their legs given back to them for the first time in many weeks. Soon they were led out the door, arms bound, and across the lawn. They could see the rows of spectators stir and hear the sudden shift in sound as they stepped into the winter sunlight. Aware of the intense attention, they made exaggerated signs of their unconcern, “crowding and jostling each other to be ahead, just like a lot of hungry boarders rushing to dinner in a hotel.” Delivered to the officer of the day at the foot of the gallows, they began another death song. Again they shoved at each other as they climbed the steep steps, and then they were maneuvered into position. Up the hill, they could see prairie; downslope, the Minnesota River; all around them, the encroaching whites who had closed off so many Dakota lifeways forever. For only a few moments, they could see the full extent of the crowd, five thousand people in all, what must have seemed the entire white world on hand to see them off.

Rough hands now slid thirty-eight separate ropes over their heads to rest heavily on their shoulders. Their caps were rolled down over their faces, and one by one they lost sight of the world. All of existence became their own singing and the sounds of the murmuring crowd. A commotion erupted to one side as one of the prisoners improvised a vulgar ditty naming the location of a decapitated body, and then a collective gasp sounded as another of their number managed to drop his pants and undulate his naked lower half at the whites. A small struggle ensued as the man’s leggings were hoisted up, and then it was time.

Sixteen minutes had elapsed since the prisoners had emerged into the unusually mild winter air. In the hush, a sharp spoken order was given, followed by the sound of three deliberate drumbeats.

In the moment that Chaska “passed into eternity,” Sarah Wakefield was two hundred miles to the east, in Red Wing, a Mississippi River town along the Wisconsin border named after a Dakota chief who had decades earlier vied with Little Crow’s father as the most influential leader in the Mdewakanton world. For eight weeks after her release, she and John had lived in their old house in Shakopee, but for reasons unknown she had left her husband in early December and taken her children with her across the state. She would soon return to him, and perhaps the temporary removal was unrelated to her traumas of autumn, but the timing suggests deeper and more lasting stresses at play.

Soon after arriving in Red Wing she had opened a local paper and read the “black list” of thirty-nine men slated for execution. There she had seen the name of Chaskaydon, who was described as having been “convicted of shooting and cutting open a woman who was with child.” Knowing well that the name was as common among Dakota men as her husband’s was among whites, and knowing that her Chaska had not been tried, much less convicted, for any such crimes, she “felt it was all right with him” and pushed the execution away from her thoughts as best she could. That episode in her life, she felt, was behind her. Chaska had received a reprieve, and whatever hard lash her conscience may have felt for discouraging his escape to the West, she knew that at least she would not have his hanging on her hands.

John Pope, in the meantime, had been in his new headquarters in Milwaukee since November, planning a spring offensive against Little Crow and whatever allies he might have found, a force that in Pope’s imagination amounted to many thousands of mounted men, fierce Plains warriors all. More important to Pope, though, was his new location so much closer to Illinois, his home state and the place where his political and social connections were still tightest. There he could mount a concentrated political campaign aimed at achieving his return to active duty against the South.

Governor Ramsey was in Saint Paul, and Henry Sibley was upriver, in Mendota, having assumed command of the newly fashioned “Minnesota district” of Pope’s military department. For the first time since August, Sibley was finally free of the responsibility of prosecuting the Dakota War, and he was looking forward to a winter spent putting his political and business affairs back in order. He knew that he might be leading Pope’s columns of men into the Dakota Territory the following spring, but that action was months away and making few demands on his time here at Christmas. His home life was far more amenable now that he had acceded to his wife’s request to make a new home in Saint Paul after the new year, a move from the former trading center of the Minnesota Territory to the current capital of the state that would symbolize the completion of Sibley’s own personal evolution.

Jane Grey Swisshelm, the firebrand editor of the St. Cloud Democrat, might well have traveled to Mankato to provide a firsthand report of the executions but for the request of an unnamed state official that she “go East, try to counteract the vicious public sentiment, and aid our Congressional delegation in their effort to induce the Administration either to hang the Sioux murderers, or hold them as hostages during the war.” She had accepted the invitation without hesitation, disgusted that the “Eastern people” had “endorsed the massacre and condemned the victims as sinners who deserved their fate.” As the drum sounded in Mankato, she was in Saint Cloud, transferring ownership of her newspaper to a subordinate and hurriedly packing for a move she had already decided would be permanent. Once she had deposited her daughter with her ex-husband’s family in Pennsylvania and settled in the national capital, she planned to use her fame and high connections to see Abraham Lincoln herself so that she might talk him into speedily reinstating the executions of the remaining 264 condemned Dakotas.

As for the president, on Christmas Eve he had had a long talk in the evening with Massachusetts senator Charles Sumner about the implementation of the Emancipation Proclamation, due to take effect in seven days. On Christmas Day he and Mary Todd Lincoln had spent the afternoon making the rounds of Washington’s military hospitals to greet and thank wounded soldiers before they went home for a subdued Christmas night, their first without son Willie, who had died in February. The next day, as his execution order was carried out in Minnesota, the second floor of the White House was engaged in business as usual, the president’s mind on matters much closer to home. Most of the usual Friday cabinet meeting was devoted to hashing out the creation of West Virginia, with Lincoln’s closest advisers split three against three regarding the desirability and constitutionality of doing so.

Alone among Minnesota’s most prominent citizens, Henry Whipple intended to attend the hangings. But like many others, he had fallen victim to the unusual warmth of the season, setting out to cross the farmlands between Faribault and Mankato in the days before Christmas only to find himself stuck in the mud with a broken-down wagon and no way to make repairs in short order. But he, too, had left the condemned behind. Already he was pondering a way that he might shelter the Dakota most committed to Episcopalianism, those he had baptized before the late war and those who had acted against Little Crow and in the interest of the white and mixed-blood prisoners. The forces massed against him were powerful and many-headed: measures were moving through the state legislature to put a bounty on any Dakota scalp brought back to the capital, while the national government considered the question of the Dakota lands and annuities covered by the treaty of 1858. Even now, Minnesotans’ thirst for revenge was settling into the understanding that the state was now theirs, that the need to coexist with the Dakota had been replaced by the need to keep the Dakota out.

The disposition of Indian lands—the “extinguishing of title,” as the phrase went—had been the first priority of every leader the territory and state had known. Now, with one mass execution, however paltry and insufficient in the minds of so many, complex treaty questions and expensive efforts to civilize the Dakota could be cast aside. In the eyes of many citizens, this new state of affairs—whatever white and Indian blood had been spilled to bring it about—made for a just and logical conclusion. In the white towns of western Minnesota, shattered families who were faced with forever altered lives and pain that would not end found nothing but bitter consolation, but in the halls of two capitol buildings, one in Washington and one in Saint Paul, many politicians found a yearned-for objective realized more quickly than they had hoped. To many Dakota, on the other hand, it seemed that the story of the past twenty-five years, since the treaty of 1837, had been a single extended provocation designed to goad them into a war that would only accomplish their banishment and destruction.

No one doubted that the monetary burden of the war to Minnesota would be quickly ameliorated. The reservations were federal creations, the treaties were federal documents, and so reparations would be paid by the federal government. The annuity monies once destined for Dakotas and the white traders among them would now belong to the government and could be used wherever the government might need the money most. The reservation land south of the Minnesota River could now be held as federal land for settlers under the Homestead Act passed earlier that year: New Ulm would soon be rebuilt, white towns called Redwood Falls and Granite Falls would soon grow on the former reservation, and white farms would soon emerge on or near all of the former Dakota village sites along the river. Warehouses and levees in Saint Paul and throughout the river valleys prepared for the increase in shipping of every manner of provision. Boom times were coming.

The state’s animus toward Lincoln cooled quickly. The president had, in the end, forcefully upheld some executions. And even as he had called off others, he had agreed to hold off on the final disposition of the reprieved men rather than issue any blanket pardons. “I could not afford to hang men for votes,” Lincoln would later say to Ramsey, but in political terms the opposite was also true: he could not afford to free all of the Dakota. The 264 men had received a stay of execution, not pardons, with the promise of future dispensation that could mean freedom, extended incarceration, or even hangings—and for most Minnesotans, it seems, that was enough. Perhaps the opportunity to vote against the president’s party in November had also dampened some of their fire.

Things were moving quickly in Washington: General Sibley’s suggestion that $2 million might be a satisfactory federal contribution to the state’s recovery effort had eventually resulted in the introduction of a bill setting aside three-quarters of that amount for reparations—a total that nearly matched the entire annuity negotiated in the treaties of 1858—while Secretary of the Interior Caleb Smith had already agreed to the complete expulsion of the Dakota and the Ho-Chunk tribes, emptying the fertile southern half of the state of Indians. In the days immediately following the hanging, the messages were succinct: Sibley could telegraph Lincoln that “everything went off quietly” and Senator Wilkinson could assure Governor Ramsey that “our Indian matters look well.” As far as the Dakota were concerned, of course, there were no more “Indian matters” in the lands they had called home for two centuries. But that was, at least in part, Wilkinson’s point.

Considering all of the prominent Minnesotans absent from the hanging—General Sibley, Governor Ramsey, and Bishop Whipple, most notably—it is remarkable that somewhere amid the thousands of spectators stood a man whose name would one day far exceed theirs in national and international renown. In fact, when William W. Mayo set out from Le Sueur for Mankato sometime during Christmas week to watch thirty-nine Dakota Indians meet their death, he left two young boys at home, Will and Charlie, who would one day become the most famous siblings in the medical world. Mayo, who had played a small but valorous role in the recent war, sought no special personal closure or satisfaction in the Christmas executions. Rather, it was the education of his children in the structure and construction of the human body that brought him to the hanging—that, and the fact that he had been in the Minnesota territory long enough to form a small personal connection with at least one of the condemned men.

An emigrant from England, son of a ship captain and relative of several famous doctors, schooled in medicine and chemistry at Manchester and Glasgow, Mayo had come to America in 1845; he found work as a pharmacist in New York’s already notorious Bellevue Hospital and then in Buffalo before finishing his schooling at Indiana Medical College. Married shortly thereafter, he made another stop in Saint Louis before settling for good in the Minnesota Territory in 1854, where, he wrote, “I was perfectly charmed with the new country and I was anxious to see it in all its wild beauty and to tread where the foot of man had never trod before, unless it be that of the Indian.” He first considered setting up shop in the northeastern tip of the future state, in Ojibwe territory, but finally settled on a farm near Le Sueur, then in the town itself, where he had slowly built his practice while he ran the town’s ferry across the Minnesota River and published its Democratic newspaper for extra income.

After the news of Fort Sumter, Mayo had lobbied loudly to become surgeon of the Third Minnesota Regiment, destined for duty in Kentucky before returning to take a major role in the action at Wood Lake; rebuffed, he continued his family practice and became an examining physician for new recruits instead, preparing lists of the “halt, lame, and blind” in the county and assisting in recruitment efforts when Lincoln’s call for 300,000 went out after Second Bull Run. When news reached Le Sueur on the morning of August 19, 1862, that the Dakota were attacking traders and settlers, he set out for New Ulm and arrived one day later to find the town full of dead and wounded from the first, aborted battle, its citizens in a panic at the prospect of another, more substantial attack. Setting up shop in a hotel named the Dacotah House, he had spent the second day of battle performing amputations and other surgeries, stepping outside in one instance to shake his surgical knife in disgust at a pair of citizen-soldiers running away from the action. That had been the extent of his involvement in the war, until the place and date of execution was published in his hometown newspaper.

At the cutting of the central rope, a loud cheer had gone up from the crowd surrounding Dr. Mayo, who watched most of the hooded men kick and struggle for several minutes; the ropes had apparently not been long enough to snap their necks cleanly and so suffocation had done the killing work instead. Twenty minutes after the platform fell away, finally, the bodies were examined and all life “pronounced extinct.” The corpses were then cut down, placed in four army wagons, and driven downriver a short distance to a long, shallow, unmarked grave located amid a copse of swamp willows by the water. Thirty-eight bodies were thrown into the pit one by one, after which they were roughly positioned in two rows, feet to feet and heads outward, covered with blankets, and buried under a loose pile of sand.

Such a grave was designed to be anonymous and, given the floods that would inevitably disturb the bones, quite temporary. But no waters would ever wash these men away. Most of the thirty-eight stayed in their resting place only until dark fell, when Mayo and a group of his fellow local doctors, at least a half dozen in number, arrived with spades and wagons, hoping to grab their prizes before a gang of less academically minded men following close behind beat them to it. Stealing the corpses of the indigent, criminal, and unmourned was a habit of doctors across the world during the nineteenth century, and Mayo’s local prominence may have given him first choice of the cadavers. The body he chose was, he believed, that of Cut Nose, the most feared of all the combatants, convicted of participating in the murders of two men, four women, and eleven children in the settlements on the first day of the war. According to Mayo, the infamous Dakota was easily identified by an old gash to his face once the sand, blankets, and caps were removed.

The Indian’s size may have mattered to Mayo; probably the tallest and largest man among the condemned, Cut Nose was an imposing physical specimen. But Mayo had also known him, if only in passing, thanks to a random encounter early in his days of making the rounds near Le Sueur, when Cut Nose and two other warriors, all described by Mayo as drunk, had emerged from beside the road for a discussion about the doctor’s fine horse. Mayo, fearful that his mount was about to be stolen from him, charged at the Indians, turned, and rode off. Cut Nose was the symbol of massacre for many whites, a man who killed with a unique fury and was the central character in any number of credible and not-so-credible stories of babies nailed to trees, pregnant women clubbed to death, or young boys chased down and scalped in the fields.

Once Mayo and the other doctors had departed the gravesite, most of the remaining corpses were divvied up by other hunters after other prey. John F. Meagher, an Irish immigrant who owned a metalsmith’s shop on Front Street, left much less of an impression on history than Mayo, but he, too, had a connection to the dead and wished to fulfill a particular purpose. As Meagher later wrote, he accompanied the doctors with a team and wagon for the purposes of making “sure that all who were executed were good Indians,” a play on the oft-repeated saw about the only good Indians being dead Indians. As the bodies were removed, he found what he was looking for. “Among those resurrected was Chaska Don,” wrote Meagher. “We all felt keenly the injury he had done in murdering our old friend Gleason, in cold blood. I cut off the rope that bound his hands and feet, and cut off one brade of his hair with the intention of sending them to Gleason’s relatives should I hear of there whereabouts.”

By the time Mayo, Meagher, and the others had gone, only a few of the bodies remained, Chaska’s perhaps among them. But when spring came, those too would be impossible to find, as would the grave itself. The erasure would be complete. The gallows, too, would be no more, despite the desire of some to save the structure for future executions. An auction was held, and piece by piece it was carried off to become emblems of satisfaction, markers of grief, totems of revenge, family keepsakes to be handed down from generation to generation. Still, if another such device was required—and many hoped fervently that one would be—they now knew that killing forty men in a single moment was not so difficult a task as it might have first appeared.