As thirty-eight of his kinsmen mounted the scaffold in Mankato, Little Crow was six hundred miles away, having traveled several times that distance since late September, his circuitous route reported breathlessly by Minnesota newspapers that were never quite sure where he was. His new home was a gathering place for many Indian tribes, a body of water that whites called Devils Lake, a mistranslation of the Dakota name Mdewakan, meaning, roughly, Mysterious Lake. But both monikers seemed a snug fit. Seventy miles south of the Canadian border in the northeastern quadrant of the Dakota Territory, Mdewakan was a place of legend among the Dakota, who told stories of giant whirlpools that pulled men under the water, of never-ending floods that spread to cover the entire world, and of a hideous and ancient monster who had come to this spot through an underground river.

A white traveler might concur with the description of John Charles Frémont, the Union general, who had once called Devils Lake “a beautiful sheet of water, the shores being broken into pleasing irregularities by promontories and many islands.” But that was the lake viewed only in one moment. One needed to watch the water over time to stand in awe of its strange and singular behavior. No river or stream flowed into or out of Devils Lake, making it a rare American example of a “closed-basin” lake, a broad bowl sunk into the northernmost Great Plains whose waters did not simply rise and lower with the rains; rather, it filled and emptied, all of its water unfit to drink, brackish and full of minerals. From century to century the surface level of the lake might change by forty feet or more; in the memory of their grandfathers it had been nearly dry, but now, in early 1863, the water was near its utmost height and mostly frozen, spreading its irregular bays and fingers across more than 200,000 acres of land and threatening to overspill its highest, outermost banks.

Many spirits resided here. And as the new year began and the spring thaw slowly approached, so did many thousands of Indians. Little Crow had arrived in December to join a great gathering of tribes, but whatever reports to the contrary might have been reaching white ears, this was no unified gathering of armies on the plains. Rather, it was a collection of smaller winter villages spread out in defensible positions among the fingers of land created by the lake’s many bays, of camps along the Sheyenne River to the south or on the banks of a series of smaller freshwater lakes to the north, where Little Crow and his followers were now staying. From the east came the Upper Agency Dakota, the Sissetons and Wahpetons; from the north arrived bands of Ojibwe and Red River Métis, those descendants of French traders who, unlike the Dakota mixed-bloods, had kept themselves and their culture separate from whites and Indians alike; and from the west came Lakotas, Yanktons, and Yanktonais, even some Mandans and Hidatsa and Arikira from the upper Missouri River. The eight thousand or more Indians gathered on the northern plains were in no sense one people and shared no common agenda, but their concentration did give Little Crow a final opportunity to nurture a frayed and fast-fading dream of forming a confederacy bent on returning to Minnesota and teaching Sibley and his army the full meaning of Dakota war.

In August, Little Crow had talked eloquently of dying with his warriors, but he hadn’t said anything about when or how that might happen. Early in the war, probably at some point soon after he’d begun the westward retreat from New Ulm, he had made the decision that, should he fail to accomplish his goals in the Dakota Territory, he would head north toward Canada and the British presence there. In his childhood Little Crow had heard stories of his grandfather’s participation on the side of Britain in the War of 1812, an alliance marked by many war councils, promises of fealty, gift exchanges, and side-by-side fighting, including a siege of Fort Meigs and a futile assault on Fort Stephenson, both near the westernmost tip of Lake Erie. His grandfather’s allies during those battles had included Tecumseh, who would perish later in the war, shot during the Battle of the Thames. There was something of the legendary Shawnee leader in Little Crow’s endgame strategy: his first hope, however inchoate, was to unite his people into one great force, enlisting the Dakota of the plains, the horse riders and buffalo hunters, into the war that many whites had now named after him, so that he might create such trouble for Washington that an advantageous peace might be made. All the while he would keep one part of his mind on the 49th parallel, the line across which lay Canada and the possibility of arms and refuge.

After an initial stop at Devils Lake in October, Little Crow had traveled hundreds of miles across the plains to the Missouri River, where he discovered six hundred lodges full of Yanktons and Yanktonais, his Western Dakota kin, raising his first hope that he might find willing warriors to follow him back into battle. In early December the Indian agent to the Yankton tribes had written to Washington to say that Little Crow and as many as a thousand Dakota warriors were “now on the Missouri River, above Fort Pierre, preparing for an early spring campaign against the whites. They are murdering all the whites in that region.” The second sentence was false, though scattered killings had taken place, but the first sentence was true, even though the count of fighting men was probably exaggerated. For a time it seemed Little Crow’s councils might bear fruit, but negotiations broke down close to Christmas, when the Yanktons and Yanktonais prepared to move their encampment and sent men to guard their traders at Fort Pierre without making the smallest commitment to the cause of war.

This had left Little Crow little choice but to move well north along the Missouri River toward the region called the Painted Woods, where he might recruit the Mandan, Hidasta, and Arikira peoples who made their winter lodges there. Little Crow and his advance warriors made signs of peace as they approached, but the Mandans only shot at them and Arikiras made ready to surround them. News of Little Crow’s mission and the danger it would pose to those appearing friendly to his cause had apparently preceded him. Here, in the open spaces of the Dakota Territory, where tillable farmland was in shorter supply and the discovery of gold and other precious ores was yet to come, the Dakota still greatly outnumbered white settlers and had not yet felt the full military and commercial force of the United States. Little Crow, a man who seemed to many of them bent on bringing down that might on the heads of all of the western Indians, was as much a threat to their way of life as any far-off federal government.

His options growing short, Little Crow knew that shelter and provision for the winter would soon become more important than forming an army, and so he headed back to Devils Lake. Here he crossed paths with Standing Buffalo once more and discovered that their plans seemed to be converging even if their goals remained far apart. In late December, Standing Buffalo had left with a delegation of Upper Dakota Indians to move north up the oxcart trails paralleling the Red River and into Canada, where there were many métis and few white soldiers, in order to look for a place of peace away from the carnage. Little Crow did not go, but he watched carefully. If Standing Buffalo received encouragement, or even simply a cordial welcome, he might have one more card to play.

As Little Crow roamed farther and farther north, ever more distant from the old places of his people, 1,600 of his fellow Dakotas were living under the eye of white soldiers not five miles from where the bark lodges in his former village of Kaposia had once stood. No feature of the landscape was more important to the Eastern Dakota than the confluence of rivers, and no confluence was more important to Little Crow’s band, the Mdewakanton, than that of the Minnesota and Mississippi. Long a vital nexus tied to trade, hunting, shelter, travel, and the spirit world, it was now a prison, center of a deep spiritual dislocation and despair that no white could fully understand.

Surrounded by a twelve-foot-high fence, their tepees arranged across three acres in precise rows “with streets, alleys, and public square,” they now lived their days in stasis. Abutting the river on “a low flat place in parts of which the water still stands,” the captives had endured the harsh, changeable winter as best they could, but their spirits remained low. As one mixed-blood wrote, “We had no land, no homes, no means of support and the outlook was most dreary and discouraging.”

A teenage Wisconsin private named Chauncey Cooke left a written record of his first tour of infantry duty in a series of lengthy, precocious letters to his mother that he later edited for publication. In one, he described the scene at Fort Snelling: “Papooses are running about in the snow barefoot and the old Indians wear thin buckskin moccasins and no stockings. Their ponies are poor and their dogs are starved.” Cooke also engaged in what was apparently a common pastime of visitors and soldiers alike by, in the words of one visiting pastor, “lifting up the little doors and looking in without saying as much as by your leave.” More attuned to the helplessness and degradation of the captives than most whites, Cooke noted the “angry eyes” that met him in return. “Nearly all of them were alike,” he wrote. “Mothers with babies at their breasts, grandmothers and grandsires sat about smouldering fires in the center of the tepee, smoking their long stemmed pipes, and muttering their plaints in the soft gutteral tones of the Sioux.”

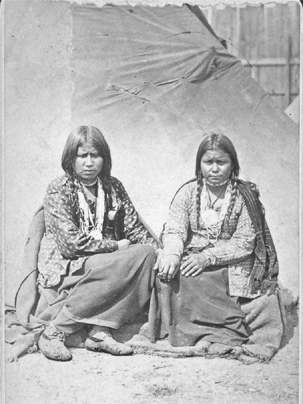

Cooke was not the only white person peering into the Dakota tepees. Beginning on the first day of their arrival, the destitute families became curios for politicians, reporters, and men bearing cameras. Very few photographs remain from the war itself, but these 1,600 Dakotas represented no danger to whites and were now close enough to the ever more numerous studios in Saint Paul that a windfall could be had. No Mathew Brady or Alexander Gardner had roamed the battlefields of Minnesota, but still “The Dead of Antietam” found an analogue in many dozens of portraits and commemorative postcards of the captive families held at Fort Snelling. For the first time, a rich visual record emerged. The bluff one hundred feet above the camp provided a dramatic view of the tepees, highlighting their arrangement in tightly packed straight lines and providing an unsettling contrast to the circular layout of a traditional Dakota village. But it was the photos of individual Dakotas that sold best, images that banked on all of the usual associations with Indians: nobility, savagery, primitiveness, and most especially tragedy. Indians captivated the white imagination precisely because they seemed to be vanishing.

Of the true lives of their subjects the photographers knew nothing, and the photos did little to reveal individual personalities. Still, if the pictures were intrusive and patronizing, they were also mesmerizing. The stock shot captured a woman seated outside her tepee, staring forward without expression; only beneath flat eyes did something seem to stir at a great remove from the man behind the camera. These images were mailed all over the United States and even overseas. Some also found their way into the hands of the captive Indians at Mankato, traveling with letters that were first censored by Major Joseph R. Brown and other representatives of the government.

The list of people, land, objects, and freedoms that been taken away from the Dakota families was long. Their wagons, yokes, and harnesses were now lost or had been confiscated, while all of their horses, oxen, cows, and mules had died, vanished, or been sold to pay for their upkeep. To make them winter on an open flat protected only by a two-inch-thick wooden fence was, in their eyes, insanity; as the missionary John P. Williamson had written in mid-November, “They would like to have some place in the woods a few miles off and as they are here I think it would be the best they could do for them. It is going to be a hard time for the Christian Indians. Temptation comes in like a flood. If their enemies cannot destroy them by the sword they will destroy them by corruption.”

On November 19, before the enclosure was completed, the Saint Paul Pioneer reported that “an Indian squaw” had been killed and added, “we doubt not but there will be many such accidents if Abraham don’t consent to let them hang.” A fusillade of dueling articles had then appeared doubting the charge or demanding an investigation and punishment, until a letter published three days later in the Saint Paul Daily Union seemed to have settled on an agreed-upon version: “The truth of the matter appears to be, that the squaws have been in a habit of gathering wood for their campfires and one of them, thus engaged, having wandered some little distance from the encampment, was seized by a number of soldiers and brutally outraged.”

Another series of general orders, almost identical to those issued by Sibley and Marshall on the marches of early November, had threatened court-martial and execution should such incidents recur, but the camp was too large to create any confidence in their enforcement. In the end, the threat of disease did more than anything else to keep renegade soldiers and parasitic civilians away. The measles raged up and down the rivers that winter, along with diphtheria and typhoid, all of which made their way into the camp in short order. As Stephen R. Riggs wrote in mid-December, “Since the Dakota camp has been placed at Fort Snelling, quite a number have died of measles and other diseases. I learn that their buried dead have, in several instances, been taken up and mutilated. They are now keeping their dead or burying them in their tepees.” Henry Whipple wrote to his wife, Cornelia, predicting that as many as three hundred Indians would die before the warmer months, and shortly thereafter Riggs reported that “the crying hardly ever stops” and that “from five to ten die daily.”

The day of the hangings brought the camp low, the embers of white retribution stoked by a small, vocal number of soldiers who, as always, made it their purpose to make the prisoners aware of outside events they might find distressing. The Dakota families took little solace in Lincoln’s intervention, not with thirty-eight dead and the final disposition of the reprieved men still as mysterious as their own. “The ever-present query was, ‘What will become of us, and especially of the men?’ ” wrote John P. Williamson, the missionary’s son. “With inquisitive eyes they were always watching the soldiers and other whites who visited them, for an answer, but the curses and threats they received were little understood, except that they meant no good. With what imploring looks have we been besought to tell them their fate.”

Williamson and Samuel Hinman, Bishop Whipple’s protégé, had traveled every step of the way with the captive families and now lived among the Dakota in their encampment. After the executions they were joined for many days at Fort Snelling by Father Ravoux, Stephen R. Riggs, and the old Presbyterian missionaries Samuel and Gideon Pond, along with various clergy from Saint Paul. Daily services were held by each of the various denominations, wrote Whipple, noting that the prisoners who attended “were subdued, and felt very sore because their chiefs and medicine-men had misled them in their prophecies of a successful war.”

The bishop visited once a week, performing baptisms and confirmations, accepting surrendered charms and medicine bags, and conferring with the other religious men on the site. Noting a set of stitches in Samuel Hinman’s scalp, Whipple extracted the story from him: one night after dark “some white roughs from St. Paul” had forced their way into the camp and assaulted Hinman, who was left bleeding and unconscious but not bowed. “Those who live much with the Indians,” wrote Whipple, referring to Hinman’s stoic acceptance of his scar, “seem to imbibe their spirit of fortitude and apparent indifference to suffering.”

Whipple now began to concoct a plan to shelter those former members of the peace party who wished to stay in the state and become Episcopalians. At the same time, he wrote perhaps his most pointed and personal letter of the war, having heard, accurately, that Henry Sibley was seeking the go-ahead to execute fifty of the reprieved prisoners still held in Mankato and place the remainder in prison for life. On March 7, Whipple wrote to the general, saying he was “sure that our friendship will be a sufficient apology for addressing you upon the subject of the Indian prisoners at Mankato.” Then he continued in an entirely atypical vein, calling Sibley to personal account.

Your official report to Gen. Pope states explicitly that these men came to you under a flag of truce. Captives have declared the same to me … Officers have told me privately that the trial was conducted with such haste as to forbid all justice. I have even been informed by one high in command that of those executed there was one innocent man. The civilized world cannot justify the trial by military commission of men who voluntarily came in under a flag of truce … I have hitherto refrained from saying one word to any public officer. May I not ask you to look at this subject again in this view of the matter. I believe you will change your views.

The request was remarkable: he was asking Sibley to examine his own conscience, to consider the moral propriety of disregarding the flag of truce the general himself had encouraged and the results of trials that the general himself had ordered, organized, and overseen.

This may have been the only such letter Sibley ever received in the course of his career, and he replied with heat. “There were no such flags, strictly speaking, used,” he wrote, the “strictly speaking” adding a touch of hair-splitting that belied his seeming assurance. He employed no such legalese, however, in explaining his stance toward the captured and surrendered Dakota. “If I had not received the President’s orders to the contrary,” Sibley wrote, “I should have executed these Indians as fast as convicted.”

None of the hardships of Sarah Wakefield’s captivity—the initial burst of terror, the endless nights full of fear, the insults of drunken Indian warriors, the uncertainty of her fate—were as harrowing for her as the first few months of her freedom. The “trouble” about which she wrote so frequently and in such broad strokes seems to have been less social than moral, some notorious event in her past or tendency in her present that caused the church to keep her at arm’s length and forced her personal relationship to God out of the usual channels. And now she was also trying to make sense of Chaska’s death, an event that seems to have haunted her every day.

At some point after her move to Red Wing and in the new year, she had picked up a newspaper and found there the reprinted “confessions” gathered by the Reverend Stephen R. Riggs. Reaching the transcription of Chaska’s interview, she saw her own name printed twice, as if to make sure she could make no mistake in her reading: “Then came along Mr. Gleason and Mrs. Wakefield. His friend shot Mr. Gleason and he attempted to fire on him, but his gun did not go off. He saved Mrs. Wakefield and the children, and now he dies while she lives.”

Guilt lashed her, and over one forty-eight-hour period in March, she wrote two unnerving letters that demonstrated her precarious state of mind. The first, on the 22nd, went to Riggs, expressing her anger over Chaska’s mistaken hanging and demanding an explanation. “I understand that Chaska’s mother hung herself the day he was executed,” she began. That piece of information, wherever she’d heard it, was incorrect, but her tone was set and she went on, one sentence after another, in rushed and rattled prose such as she never wrote in any other surviving private or public document.

I would be pleased to learn the particulars also in what way and by whom the mistake was made whereby an innocent man was hanged. I did not fully understand the day you was here, as I am about publishing a narrative of my life among the Indians every thing of any moment is of course necessary that is any way connected with that family names of course I care not to bring in to print but every occurrence I shall want to give to the public.

Here is the first suggestion that the narrative she would soon publish, a book that would become one of the most widely known accounts of the war, may have been born at least in part out of her dismay at Chaska’s fate and her desire to create a public argument for his innocence, tied always to her need to defend herself against the charge that she had become his lover. The next day, on March 23, she poured even more of her bewilderment and grief into a letter to Abraham Lincoln. By this point the president had heard about his handling of the Dakota War from bishops, missionaries, state and national legislators, newspaper editors, citizens’ assemblies, and, indirectly, the Minnesota voters who had helped to reduce the size of the Republican majority in Congress in November. But no one else had written to him as Sarah did now, outlining an acknowledged case of mistaken identity that she viewed as entirely intentional.

“I will introduce myself to your notice as one of the Prisoners in the late Indian War in Minnesota,” she began, and then told Lincoln of her capture, Chaska’s role in her deliverance, his arrest and trial, his commutation, and the “sad mistake in the number, whereby Chaskadan who saved me and my little family was executed in place of the guilty man this man is now at Mankato living, while a good honest man lies sleeping in death.” Next she turned to a matter that Lincoln couldn’t possibly be expected to adjudicate.

I am extremely sorry this thing happened as it injures me greatly in the community that I live. I exerted myself very much to save him and many have been so ungenerous as to say I was in love with him that I was his wife &c, all of which is absolutely false. He always treated me like a brother and as such I respect his memory and curse his slanderers.

The blame, Sarah wrote, belonged to “a certain Officer at Mankato who has many children in the Dakota tribe,” a statement that could only refer to Joseph R. Brown, the former Indian agent known for his lifelong pursuit of Indian women, the same man who had come to the prisoners’ enclosure to read out the names of the thirty-nine. She referred vaguely to a “promise” made to her at the trial—an odd contention given the finding of guilt and the sentence of death—and described how she discovered the mistake via Riggs’s translations of the prisoners’ final “confessions.” Then she made a plea that Lincoln might make things right—“it would be extremely gratifying to me to have these heedless persons brought to justice”—but only in passing, as the real point of her letter seemed to be something much more personal.

I am abased already by the world as I am a Friend of the Indians. This family I had known for 8 years and they were Farmers and doing well. Now this poor old Mother is left destitute, and broken hearted, for she has feeling if she is an Indian, surely we are Brothers all made by one God? we will all meet some day, and why not treat them as such here. I beg pardon for troubling you but there is much said in reference to his Execution. The world says he was not convicted of Murder then why was he Hanged? Then they draw their own conclusions: if this could be explained to the world a great stain would be lifted from my name. God knows I suffered enough with the Indians without suffering more now by white brethren & sisters.

Lincoln received thousands of letters every year from private citizens seeking office, proposing policy, praising or condemning the conduct of the Civil War, selling goods or services, or outlining personal grievances. A high proportion of these supplicants or critics began their letters by begging the president’s forgiveness for intruding on him “amidst his multitude of cares,” or some other such phrase. John Nicolay, John Hay, and various assistant secretaries handled most of this mail and forwarded what seemed important. The president’s personal history, melancholy countenance, and well-earned reputation for compassion made him a tabula rasa upon which people wrote their dreams, hopes, anxieties, and terrors, whether or not he was able to respond. Bishop Whipple had shaken Lincoln’s hand, while Sarah Wakefield’s message seems to have disappeared into a great whirlpool of anonymity. But both were saying the same thing in their appeals for a more humane consideration of the plight of the Dakota.

“God and you Sir,” Sarah closed, “protect and save them as a people.”