In 1868, five years after Little Crow’s death, a fashionable couple out for a night in the capital could go to the Saint Paul Opera House and pay one dollar apiece to view “The Panorama of the Indian Massacre of 1862 and the Black Hills,” barkered as “The Great Moral Exhibition of the Age!” and “The Most Extraordinary Exhibition in the World!” and promising “War Dances, thrilling escapes, and landscape views.” Ushered to their seats, they would have found the hall dark except for a fascinating apparatus, a screen six feet wide and a dozen feet high, designed with vertical rollers that held 222 feet of canvas on which three dozen images had been painted. As a man standing next to the device slowly turned an oversized crank, the story of the Dakota War paraded across the screen to the accompaniment of music.

The entertainment was new, sensational, and utterly captivating. Part of the point was the seeming reality of the panorama itself. “Ladies and gentlemen,” the breathless narrator began, “the cause of the massacre, a portion of which we are now about to exhibit to your view, cannot be given. But a short account of the condition of the country will suffice to exhibit this tragic epoch in our country’s history in its proper light.” The war’s causes weren’t the point—no complex historical, political, racial, or moral questions would be asked of the audience—so what was this “proper light”? John Stevens, a sign painter by training, had moved beyond advertising and into the more lucrative realms of sensation and spectacle. His was not the only panorama traveling the country—the Civil War gave birth to hundreds—and like all of the others its brightly backlit images served many purposes: to titillate and awe, certainly, but also to confirm the public need to place the events of 1862 in the great sweep of the settlement of the West, joining the yeoman farmers of the Minnesota River Valley to the pressing imperatives of Manifest Destiny.

The mode of narration was epic and lurid: “Tumultuous horrors rent the midnight air, until the sad catalogue reached the fearful number of two thousand human victims from the gray haired sire to the helpless infant of a day, who lay mangled and dead on the bloody field. The dead were left to bury the dead; for the dead reigned there alone.” Indeed, much of the exhibit consisted of a long catalogue of killings and maimings, scenes dripping with hatred for a people who now seemed long gone.

The idea of executing three hundred Indian warriors aroused the sympathies of those far removed from these scenes of human butcheries, and the president was importuned by all unreasonable bounds for the release of these savages. The voice of the blood of innocence was crying from the ground. The bewailing of mothers bereft of their children was hushed in the louder cry of sympathy, and for the condemned the tide of sympathy rolled on, and the persistent applications to the president were successful, and in place of three hundred and three condemned by a military court, only forty were ordered to be executed.

Like Buffalo Bill’s Wild West show many years later, Stevens’s Sioux War panorama was a collective catharsis, a safe but thrilling coda to an unimaginably violent era. The success of the exhibition depended on the viewer’s belief in a certain vision of history: playing to packed houses in Minnesota, Wisconsin, and Iowa, it put the settlers and soldiers of those states at the center of great events and gave them a status equal to those more famous locales on the national map. The first image of the panorama—a nine-square montage of Lincoln, his cabinet, and, for good measure, Jefferson Davis—drove home the point: What had happened here was exciting. What had happened here was awful. And what had happened here mattered to everyone.

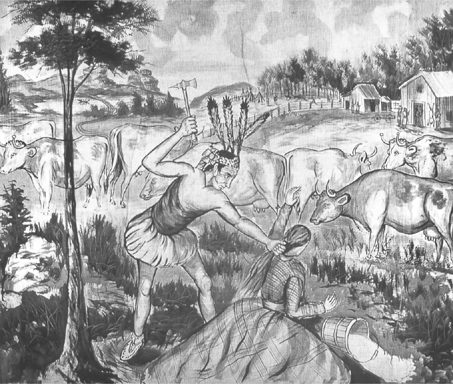

The portraits of the president and his advisers were juxtaposed with another panel featuring a similar collection of Indian faces: Little Crow, Cut Nose, Little Six, and other infamous leaders, including Chaska, whose history was now simplified to fit the needs of the narrative: “Shaska, one of the prominent actors in this fearful drama, was the murderer of George Gleason and the capturer of the Wakefield family.” The rest of the show rolled by, image after image made of crude lines and garish hues: houses afire with Dakotas riding across the fields upon defenseless farmers; two white women being killed with a single bullet; and of course, the hanging, an image frozen just before the moment of the drop.

Imagine being in that audience, the show proposed, in order that viewers might marvel at being in this audience. The final image, “Minnesota Fruit,” made clear the tale’s happy outcome: three women in dresses attended a tree out of which grew not apples, but newborn white babies.

Stevens’s panorama seemed to be many entertainments in one, looking to the past, present, and future with its mix of ages-old iconography and brand-new technology, but it was just one voice raised in an outburst of postwar storytelling. While thousands of Dakota prisoners, exiles, and refugees sat around campfires and in lodges in a dozen different far-flung places and retold the story in their own ways, unrecorded in print but remembered generation after generation, tens of thousands of whites turned to a set of ready-made popular genres to live and relive the final months of 1862, a hunger that would ebb and flow but never fully subside. Beginning within weeks of the execution, the citizens of Saint Paul, Milwaukee, and even Chicago were inundated with letters, pamphlets, songs, speeches, poems, photographs, drawings, dime novels, and popular histories. For an event that had slipped into the headlines under the cover of the American Civil War, the Dakota War of 1862—or Little Crow’s War, or the Dakota Uprising, or the Minnesota Massacre, or the Dakota Conflict, depending on the era, author, and point of view—would come to have a dizzying number of chroniclers.

At the time that John Nicolay carried Lincoln’s Annual Message to Congress, he had been penning two articles of his own, one on the affair with Hole in the Day for the January 1863 issue of Harper’s and the other on the “Sioux War” one month later for the Continental Monthly. Nicolay had remained a frequent journalist after his move to Washington, D.C., often publishing anonymously, sometimes acting as a mouthpiece for Lincoln, and sometimes writing independent commentary. His article on Hole in the Day was even-handed, complimentary of the Ojibwe leader, and steeped in detail; it made good use of his immediate experience of the event. His article on the Dakota War—which was widely read and considered a key source—was a different animal: relying on thirdhand accounts and nebulous newspaper reports, Nicolay wrote in great brushstrokes of deepest purple, appealing to “hearts appalled by the gleam of the tomahawk and the scalping knife, as they descended in indiscriminate and remorseless slaughter.”

Six months later Harper’s published its own twenty-four-page account of the war, augmented by seventeen drawings from the pen of Minnesota soldier Albert Colgrave, many after photographs by fellow enlistee Adrian Ebell, who was also the author of the article. Most of the magazine’s readers, including many in Minnesota, had little experience with Indian reservations and could not picture the drama’s major players in their minds’ eyes, so Colgrave’s illustrations became their first and only look at the places and people involved: the Upper and Lower Agencies, the villages of traditional Indians and the farms of cut-hairs, the faces of Little Crow and William Marshall, the assault at New Ulm, the scenes at Camp Release and Camp Lincoln.

Closer to home, the Mankato Weekly Record made an unprecedented editorial decision to devote the entire front page of one February 1863 issue to a single engraved image. The often-imitated point of view was taken at an angle to the gallows, foreshortening the scene into a set of thick diagonal lines growing ever longer as they radiated outward from the scaffold: the condemned men, the double rows of foot soldiers, the single row of cavalry, and behind the cavalry masses of citizens spilling off the drawing’s edge. In the center of the picture, an American flag rose high above the scene atop a needle of a pole. The Dakota themselves stood on the platform, blindfolded by their caps, their knees flexed in anticipation of the drop. In the lower left corner, a team and wagon waited to cart the dead bodies away.

Isaac Heard, Sibley’s court reporter, used his access to the stories, testimony, and transcripts generated by over four hundred trials to help him write his History of the Sioux War and Massacres of 1862 and 1863, in which he affected an objective, reportorial tone that did nothing to mask his central purpose, which was to justify the conduct of the military commission. This was not as pro-white a stance as it might seem, as many of his readers would have concurred with Pope’s original wish to execute the Indians as soon as they were captured, military commissions be damned. And Heard’s account was at least based on firsthand experience and in-person testimony. The other major history of the conflict to appear in 1864 was written by an influential Saint Paul schoolteacher named Harriet Bishop, who pretended to offer a recitation of events but was far more concerned with placing the reader in the hearts and minds of the combatants, such as she viewed those hearts and minds. In Bishop’s telling, the hearts of any Dakotas not baptized into the Christian faith were dark and only prone to becoming darker. In the end, Dakota War Whoop took so many liberties with dialogue, motivations, and thoughts to which Bishop was never privy that it was essentially a dime-store novel very thinly disguised as nonfiction.

No other genre of writing, however, approached the popularity of the captivity narrative. Local journalists and book printers beat the bushes in search of anyone with firsthand experience of the Dakota camps and a desire to talk, and over the next thirty-five years many dozens of such tales were published. Most cleaved to a set of standard elements—a trial by suffering, the deliverance by a just and merciful God—to produce an allegorical contest between primitivism and civilization. “The massacre was merely an expression and demonstration of the savagery and barbarism existing in every Sioux Indian,” wrote one captive, painting the contrast between good and evil in the starkest possible terms. These were didactic works as much as narratives, taking the events of 1862 out of their chronological continuum in order that the future could now proceed without undue discussion of the past.

Exceptions did exist to this unquestioning view of the war, the first and most notable among them Sarah Wakefield’s own memoir, Six Weeks in the Sioux Tepees. The book appeared in autumn of 1863, just months after Sarah wrote her final letters to Lincoln and Riggs, and some of it must have been written while she lived away from her husband in Red Wing before she returned to Shakopee. It is difficult to say today how wide the initial readership for Six Weeks was—few original editions still exist—but there was apparently enough interest in her story that she pondered its appeal in her home state of Rhode Island and offered “a liberal discount” for “local traveling agents” to sell the book around Minnesota and surrounding states. For such agents, the bet was a good one. Sarah was still notorious then, so much so that readers could experience a certain kind of thrill by buying or borrowing a copy to read about this woman who had, they’d heard, fallen in love with one of the redskins. But whatever prurient motives her readers might have, Sarah’s purpose was not to titillate, to entertain, or even to educate. Her purpose was much more personal.

I wish to say a few words in preface to my Narrative; First, that when I wrote it, it was not intended for perusal by the public eye. I wrote it for the especial benefit of my children, as they were so young at the time they were in captivity, that, in case of my death, they would, by recourse to this, be enabled to recall to memory the particulars; and I trust all who may read it will bear in mind that I do not pretend to be a book-writer, and hence they will not expect to find much to please the mind’s fancy. Secondly I have written a true statement of my captivity; what I suffered, and what I was spared from suffering, by a Friendly or Christian Indian, (whether such from policy or other motives, time will determine.) Thirdly, I do not publish a little work like this in the expectation of making money by it, but to vindicate myself, as I have been grievously abused by many, who are ignorant of the particulars of my captivity and release by the Indians.

Of the many narratives generated in the wake of the Dakota War of 1862, Sarah’s is now the most widely studied, mainly because it upsets traditional expectations of the genre and paints her in a kind of progressive light too attractive to resist. Her attitudes toward faith and the Dakota people do seem liberal for her time, and her theology, however constructed, was unusual. But her motivation in writing the book was not theological. The flat contradiction between the first and third rationales set out in her preface mirrors the contradictions in her own person. If a certain amount of bald confession was necessary, it was only so that she could make an overarching point about what she had not done.

The book’s frank opinion of the inadequacies of white military leadership and Sarah’s sympathetic stance toward the Dakota would lead her fellow settlers to publicly brand her a “traitor” and “Indian lover.” One year after the first edition of Six Weeks appeared, a German settler named Mary Schwandt, whose family had been decimated by the first round of attacks on the farms north of the Minnesota River, published a long narrative of her own in which she became one of the first to describe and criticize Sarah’s conduct in print. Schwandt wrote that Sarah and another captive were “painted and decorated and dressed in full Indian costume, and seemed proud of it. They were usually in good spirits, laughing and joking, and appeared to enjoy their new life. The rest of us disliked their conduct, and would have but little to do with them.”

In 1864, at about the same time Mary Schwandt’s story appeared, Sarah issued an expanded and corrected second edition of her book. In its preface, she complained about errors and omissions in the production of the first edition by her original printer, the Atlas Printing Company in Minneapolis, so now she worked through a hometown outfit, Argus Book and Job Printing in Shakopee, perhaps to keep a closer eye on the work or because she knew the printer personally and could trust him not to repeat the same kinds of mistakes. In any event, most of the book’s typographical blemishes were remedied and eleven pages’ worth of material added, as well as an image of Little Crow as a frontispiece. Sarah expanded the descriptions of her own suffering and further justified her seemingly “pro-Indian” or “anti-white” behavior, in every case citing either insanity or extenuating circumstances. She also more explicitly defended the Dakota of the peace party and more fully outlined Dakota motives for commencing the war, adding several examples of Chaska’s constant protection and more completely describing the blameworthy or at least ambiguous behavior of other captive women.

The largest self-contained change to the second edition of Six Weeks appeared at the very end of the narrative, where Sarah added 1,400 new words. The new edition now contained the story of her husband’s flight from the Upper Agency to the Big Woods and then back to Shakopee. The cursory reunion scene at Fort Ridgely she left untouched, still more focused on her children’s good fortune at her husband’s return than on her own. She capped her additions, and the second edition of her book, with the tale of one final postwar encounter with some of her Dakota protectors among a small band that had just returned to the state under the protection of Bishop Whipple and other clergy.

A few days since a number of families passed through here, and as I saw them I ran with eagerness to see those old faces who were so kind to me while I was in captivity. I went down to the camp (for they stayed all night in Shakopee), and was rejoiced to be able to take them some food, and other little things which I knew would please them, and for this I have been blamed; but I could not help it. They were kind to me, and I will try and repay them, trusting that in God’s own time I will be righted and my conduct understood, for with Him all things are plain. And now I will bid this subject farewell forever.

She kept her word, stepping off the stage and never reemerging as a figure of public attention. She bore two more children, Julia in 1866 and John two years later, but her marriage only worsened. Her husband drank ever more heavily, habituating several taverns for daily doses of beer and whiskey, and in February 1874 he died of an overdose of opium in their upstairs bedroom under circumstances that raised the possibility of suicide. Sarah was left with four children under seventeen and $5,000 in debt, an obligation that ate up nearly all of her assets and left her with no cushion as she struck out on her own.

By 1876 she had moved to Saint Paul, but there the documentary trail of her life nearly dries up. The few facts available indicate that she was able to buy a small plot of land and may have run a business. Her daughter Nellie, who had nursed at her breast throughout their six weeks of captivity, would graduate from Macalaster College and marry and divorce before she was thirty-five. Some records suggest that Sarah made a second marriage, but if so, it ended in divorce or a second widowhood, as she was unmarried on the date of her death, May 27, 1899.

Sarah was buried next to John in Shakopee. Her obituary—subtitled “She Was a Prisoner of the Sioux for Six Weeks During Their Outbreak”—listed the cause of death as “blood poisoning, resulting from other ailments,” and called her an “old settler, having come to Minnesota in 1854.” The notice contained no hint of controversy, no hint of her authorship of Six Weeks in the Sioux Tepees, no hint of trouble in her marriage to John, no hint of her husband’s fate, and no hint of her connection to Chaska. Sarah had taken no part in the century-closing spate of nostalgia for frontier times, a boom in demand during the 1890s for lectures, new writings, revised editions, and interviews involving captives, Indians, soldiers, or anyone else able to provide purported eyewitness accounts of the great Dakota War almost forty years earlier. It may speak to weariness—or, more optimistically, to a personal peace—that Sarah Wakefield had been content to let the new surge of interest pass her by and keep on with the business of living.

John Pope’s surprising intervention in the case of Wowinape and his support of pardons for the remaining Dakota prisoners turned out not to be aberrations. Following a brief stint as military governor overseeing the reconstruction of Atlanta, General Pope returned to the West in 1867 in order to take command of the federal government’s war on the Apache, just one of many new Indian fronts now open in the wake of the Civil War. He soon became a leading proponent of a plan to shield Indian reservations from white encroachment by situating them behind existing federal forts and placing them under the administration of the Department of War and the United States Army, rather than the Interior Department and the Indian Bureau, which he viewed as a bastion of lazy and corrupt administrators.

Pope’s plan can be read skeptically as an effort to increase his own military influence, or more generously as a genuine attempt to remove the graft and fraud so thoroughly enmeshed with the “Indian system.” He called for doing away with annuities, for careful regulation of trade, and for a tight rein on traders stationed near the reservations. Pope’s suggestions were, in fact, more radical and contentious than anything Henry Whipple ever proposed, as they would have essentially held the federal government responsible for any subsequent crimes or frauds perpetrated against the tribes. For this reason and many others, the plan was doomed from the start, and there is irony in the fact that Pope’s efforts eventually earned him a label as a controversial “reformer” and “Indian lover,” a role he grew to accept and even relish. It was an unfair label from both white and Indian points of view, however, as he never questioned the essential rightness of the concentration and acculturation policies begun so many decades before. He was in full agreement with William Tecumseh Sherman’s statement that when it came to Indian affairs the army “gets the cuff from both sides,” and had scant understanding of how much more accurate that statement was for the Indian tribes he sought to help.

Henry Benjamin Whipple’s all-out efforts on behalf of Indians would last for another thirty-eight years until his death in 1901 at the age of seventy-nine. In 1863, with the Dakota all but driven out of Minnesota, Whipple took on the cause of the Ojibwe in the northern half of the state, sparking “one of the severest personal conflicts that I have had in my life” when the members of Lincoln’s brain trust refused to listen to his accusations of fraud and double-dealing among the Indian agents assigned to the tribe. As Edwin Stanton wrote to Henry Halleck, “What does Bishop Whipple want? If he has come here to tell us of the corruption of our Indian system and the dishonesty of Indian agents, tell him that we know it. But the Government never reforms an evil until the people demand it. Tell him that when he reaches the heart of the American people, the Indians will be saved.” This wasn’t acceptable to Whipple, who, in one of the rare recorded instances of his frustration with specific individuals in power, told Commissioner Dole that “I came here as an honest man to put you in possession of facts to save another outbreak. Had I whistled against the north wind I should have done as much good.” Though new treaties were soon signed with the Ojibwe, real reform seemed as far away as ever.

In 1865, Whipple made a pilgrimage to Palestine “simply as a Christian to join the crowd of loving hearts,” and there he found in the hard, stark landscape of the Holy Land a ready analogy to the urban squalor of Chicago or the constricted space of Indian reservations. “It is plain that this is the land where Jesus found sermons for his untutored hearers in everything which their eyes saw,” he wrote. “For Him everything held a sermon to lead bewildered men to find fellowship with God.” Suffering a relapse of his lifelong bronchial condition on his return trip, he stopped in Paris, where he first heard of the assassination of President Lincoln. The only statement in his memoir about the news was brief: “No words can describe the feeling of sorrow which pervaded all classes, as if his death were a personal bereavement.”

Speaking at New York’s Cooper Union in 1866—standing on the same rostrum from which Lincoln had delivered his most famous campaign speech—Whipple spoke vehemently on the need for an Indian peace commission made of religious men and not politicians. Brought to the attention of Ulysses S. Grant, Whipple became a key consultant to the commission and one of the architects of the federal government’s peace policy, working side by side and arguing frequently with Sherman, though not to the point that Whipple couldn’t praise the general for “his singular uprightness of character and his devotion to his country.” With military authorities and other clergy, Whipple also aided in the removal of the Dakota from the parched and deadly wasteland that was Crow Creek to a somewhat more hospitable location near Niobrara, Nebraska, along the South Dakota border, and he was instrumental in the safe return of Christian Indians to Minnesota, using a gift of land from the Dakota leader and scout Andrew Good Thunder to establish an Episcopal mission near the site of the old Birch Coulee battlefield.

In the 1870s and 1880s, Whipple became one of the leading international voices of the American Episcopal church, making mission trips to Alaska, Puerto Rico, Cuba, and Florida, where, for good measure, he caught a record tarpon in the Atlantic Ocean. In 1885 he was invited to preach on the subject of American Indians at Canterbury Cathedral, and during his long stay in London he befriended a host of luminaries, including Lord Tennyson, William Gladstone, John Greenleaf Whittier, and Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. Whipple also accepted an invitation for a private audience with Queen Victoria to discuss transoceanic relations between the British Anglican and American Episcopal churches and to speak to her of a lifetime of working on behalf of the Indians. Asked to contribute a preface to Helen Hunt Jackson’s 1881 book A Century of Dishonor: A Sketch of the United States Government’s Dealings with Some of the Indian Tribes—a widely read and impassioned catalogue of broken treaties, theft of Indian lands, and military malfeasance—Whipple wrote, “Nations, like individuals, reap exactly what they sow; they who sow robbery reap robbery. The seed-sowing of iniquity replies in a harvest of blood.”

Whipple’s industriousness on behalf of his Indian wards never flagged, but neither did his belief that the only solution was white customs and white religion, which led ultimately to his support for the Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Pennsylvania. The most visible manifestation of the peace policy’s emphasis on “aggressive civilization” of the Indian, the Carlisle School took in and boarded Indian students, some as young as five, and forcibly separated them from everything that made them Indian: from their parents, their names, their languages, their clothing, their long hair, their medicine, and their customs of birth, marriage, and death. The goal was a complete erasure of self, society, and history, and some Indians complied, at least outwardly. Some who resisted, however, found themselves subject to beatings, hard labor, or confinement in a Dickensian misery mill that saw twice as many students drop out and run away as graduate in the latter part of the nineteenth century. No aspect of the Indian wars, however violent, was so painful to many Indians as this separation from culture, family, tribe, and lands.

In 1899, the Macmillan Company published Whipple’s “reminiscences,” Lights and Shadows of a Long Episcopate, and two years later the bishop died of heart failure at home in Faribault. Effusive tributes and reverential obituaries appeared in newspapers from New Ulm to Great Britain. His body was interred beneath the altar of the Cathedral of Our Merciful Savior in Faribault, after which forty Christian Dakotas sang “Asleep in Jesus.” His legacy was massive and admirable, and in the final analysis Whipple earned his reputation as a friend of the Indian. But it was, in the end, a very complicated friendship.

As Wowinape, teenage son of Little Crow, had fled in one direction away from his father’s body, so had Chauncey Lamson, killer of Little Crow, run in another. Returning later in the day with his brother, Lamson found signs that their wounded father had managed to crawl and then walk away. They also discovered that the Indian they’d killed was still in the raspberry patch, his body cold, his bare chest covered in dried blood, and two moccasins by his side. They hazarded no guesses as to the identity of their victim, but simply went to work with a large knife and removed the anonymous man’s scalp, a trophy for which Lamson and sons would be later awarded the standard $25 bounty given for the murder of any Indian found free in the state.

Next, the Lamson brothers had carried the body into the middle of the Independence Day festivities in Hutchinson and dumped it in front of a store, where the ghoulish scene was made all the more so when an unidentified individual shouted out the astonishing news that this dead Indian was none other than the Dakota war chief Little Crow. For proof, he pointed out the badly deformed wrists. Some believed him, but most didn’t, unwilling to accept that the body of such a notorious figure could be deposited so randomly in their midst. After some young boys tried to place firecrackers in the ears and mouth of the corpse, it was hurriedly taken away and buried in a gravel pit usually devoted to the bones and innards of slaughtered cattle. A few days later, a militia company led by Lieutenant James D. Farmer, who was among those convinced that he had indeed seen Little Crow’s remains, dug out the body and removed its head with a sword, probably as an exaggerated act of “scalping.” Stories of what happened next are contradictory, but eventually the skull made it into the possession of a local doctor, who placed it in a large cooking pot filled with a lime solution.

Three weeks after fleeing from his father’s side, Wowinape was found near Devils Lake. Once he began to tell his story, all doubt was removed: Little Crow was dead. By the time this news reached Hutchinson, Colonel Farmer had the skull again. He kept it in his home for another thirteen years, until he gave it to Frank Powell, a doctor and collector of Indian memorabilia who would one day contribute much of his life’s stash to Buffalo Bill Cody’s Wild West Show. Twenty years later, in 1896, when Powell decided he was finished with the trophy, he made a gift of it to the Minnesota Historical Society, then housed in the basement of the state capitol. There the skull was put on display next to Little Crow’s scalp, which had gone through its own chain of possession, from Chauncey Lamson to a county sheriff named Bates and then to the state adjutant general, who had thrown it in the trash, where it was retrieved by a janitor and turned over to the state historical society for safekeeping. Wowinape’s son Jesse spent forty-six of the last forty-seven years of his life trying to get the pieces of his grandfather’s remains returned for proper burial, finally achieving his goal in 1970.

The remains presumed to be those of Cut Nose found no such champion until the twentieth century had come and nearly gone. One year after the Dakota War, William M. Mayo became examining surgeon for Minnesota’s first district, meaning all of the state south of Saint Paul, a job that eventually led him to move his home and medical office to Rochester. He kept the skeleton he attributed to Cut Nose in a large iron rendering kettle, using the bones to explain various diagnoses to his patients and teaching his boys osteology by plucking various pieces out of the pot and asking for the correct identification. Eventually, the boys would put the skeleton on display in the front room of a new clinic bearing their name, a medical facility that would become one of the most famous and highly regarded in the world. In the 1930s the third generation of Mayos had the bones sent to the clinic’s museum, where over the next fifty years institutional memory went soft and the whereabouts of Cut Nose became confused. Finally, in 1991, at the prodding of historians and Mdewakanton Dakota elders, a forensic examination of multiple remains kept by the Mayo Clinic’s education division revealed the “high probability” that one of the skulls belonged to Cut Nose.

As for the fate of Chaska’s scalp, John F. Meagher’s search for George Gleason’s kin never paid off. Eventually he had Chaska’s hair fashioned into a watch chain that he would wear most of his adult life, until he sat down on the day after Christmas in 1887, twenty-five years to the day after the hangings, and wrote his own letter to the Minnesota Historical Society. Obviously reflecting on the momentous occasion and his life as a young man in Mankato—and probably aware of other Indian remains on display at the society—he offered his keepsake as a permanent donation. In his mind, it was time that his own needs took a back seat to those of history.

“I wore it until it was as you see about wore out,” Meagher wrote. “And now I send it to you, thinking that some day it might be of interest with the other mementoes of those terrible times and that great hanging event.”