Delacroix’s friendship with Thales Fielding and Bonington and his love of English romantic literature had awakened in him the desire to visit London. He undertook the little journey in 1825. He was much impressed by the immensity of London, the “absence of all that we call architecture,” the horses and carriages, the river, Richmond, and Greenwich; and, above all, by the English stage. He had occasion to admire the great Kean in some of his Shakespearian impersonations, and Terry as Mephistopheles in an adaptation of “Faust.” He was deeply stirred by these productions, which had a by no means beneficial influence upon his art. To his love of the stage may be ascribed the least acceptable characteristics of his minor pictures and lithographs — exaggerated action, stage grouping, and a certain lack of restraint. It is difficult to understand Goethe’s highly eulogistic comment upon Delacroix’s “Faust” illustrations, unless it was a case of faute de mieux, or that he had not seen the complete set. To modern eyes, at any rate, they are the epitome of the master’s weaknesses. The drawing is frequently inexcusably bad; the sentiment is carried beyond the merely theatrical to the melodramatic.

Next to the stage, he was interested by the works of the contemporary British artists, with many of whom he entered into personal relations. In his letters he expressed the keenest admiration not only for Bonington (with whom he shared a studio in the following year), Constable, and Turner, whose influence upon the French School he readily admitted, but also for Lawrence— “the flower of politeness and truly a painter of princes ... he is inimitable” — and for Wilkie, whose sketches and studies he declared to be beyond praise, although “he spoils regularly all the beautiful things he has done” in the process of finishing the pictures.

Unfortunately the principal work painted by Delacroix in the year after his return from England, the “Justinian Composing the Institutes,” for the interior of the Conseil d’État, perished by fire in 1871. The Salon was only reopened, after an interval of two years, in 1827, when Delacroix was represented by no fewer than twelve paintings, including “The Death of Sardanapalus,” “Marino Faliero,” and “Christ in the Garden of Olives.” The extreme daring, the tempestuous passionate disorder of the design of the large “Sardanapalus” alienated from him even the few enlightened spirits who had espoused his cause on the two former occasions. The reception of the picture was disastrous. Delacroix himself admitted that the first sight of his canvas at the exhibition had given him a severe shock. “I hope,” he wrote to a friend, “that people won’t look at it through my eyes.” The picture raised a hurricane of abuse. His own significant dictum that “you should begin with a broom and finish with a needle,” was turned against him by a critic who spoke of the work of an “intoxicated broom.” Another described him as a “drunken savage,” and yet another referred to the picture as the “composition of a sick man in delirium.” His other pictures were scarcely noticed, although they included a masterpiece like the “Marino Faliero” (now in the Wallace Collection), which Delacroix himself held to be one of his finest achievements, and which certainly rivals the great Venetians in harmonious sumptuousness of colour. In this picture Delacroix is intensely dramatic without being theatrical. Nothing could be more impressive than the massing of light on the empty marble staircase, the grand figure of the executioner, the statuesque immobility of the nobles assembled at the head of the staircase. The picture was exhibited in London in 1828, when it was warmly eulogised, which is the more remarkable as Delacroix never seemed to appeal strongly to British taste — the scarcity of his works in our public and private collections may be adduced as proof.

It was on the occasion of this 1827 Salon that the terms “Romanticism” and “Romanticists” first came into general use. Their exact definition is not an easy matter. Broadly speaking, the romantic movement in literature, music, and painting signifies the accentuation of human emotions and passions in art, as opposed to the classic ideal of purity of form. Delacroix himself did not wish to be identified with any group or movement, but in the eyes of the public he stood as the leader of the Romanticists in painting, just as Victor Hugo, with whom he had but little sympathy, did in literature.

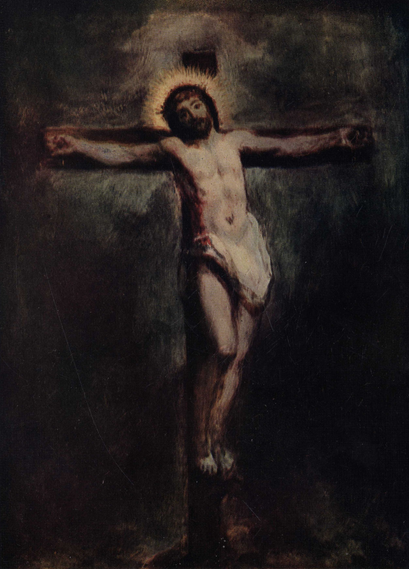

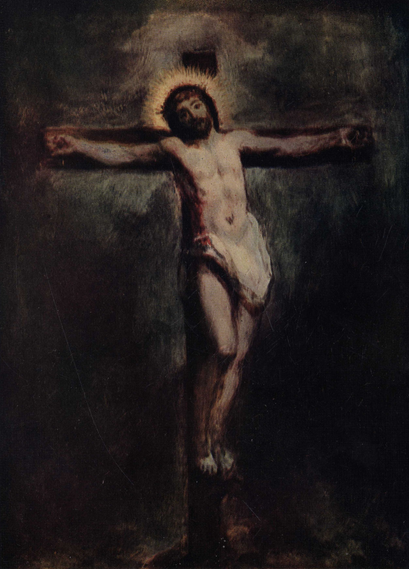

PLATE IV. — THE CRUCIFIXION

(In the Louvre)

This small panel, which forms part of the Thomas Thiery bequest to the Louvre, is a picture of precious quality and soft colouring, painted for his friend, Mme. de Forget, who had exercised her influence in official quarters when Delacroix endeavoured to obtain the post of director of the Gobelins manufactory. It was painted in 1848. There are numerous replicas in existence.

PLATE IV. — THE CRUCIFIXION

Delacroix’s “Sardanapalus” led to humiliations that he felt more keenly than the abuse showered upon him by the Press. He was sent for by Sosthene de la Rochefoucauld, then Director of the Beaux-Arts, to be advised in all seriousness to study drawing from casts of the antique, and to change his style if he had any aspirations to official encouragement. The threat had no effect upon a man of Delacroix’s strength of conviction. He yielded never an inch. He continued to follow the promptings of his artistic conscience which permitted no concessions, no compromise. During the very next year, in spite of De la Rochefoucauld’s threat, the State commissioned from him the painting of “The Death of Charles the Bold at the Battle of Nancy” (now at the Nancy Museum). The picture was not finished and exhibited before 1834, when this magnificently conceived scene of wild conflict under a threatening winter sky — so different from the grandiloquous style of the painters of the Napoleonic epopee — met with the usual chorus of disapprobation for being historically incorrect, “as bad as could be in drawing,” “incredibly dirty in colour” — the horses bad as regards anatomy, the sky impossible!

Although Delacroix was too completely absorbed in his art, which — his one great passion — took up his entire life, to take any active part in politics, he was deeply stirred by the events of the July Revolution of 1830. “The 28th July 1830,” or “The Barricade,” one of the nine works by which he was represented at the Salon of 1831, was an unmistakable confession of his political faith. Here, for once, Delacroix found his moving drama not in romance or in the history of the past, nor in the picturesque East which, owing to its comparative remoteness and inaccessibility at a time that did not enjoy the prosaic advantages of a Cook’s Agency, was still invested with the glamour of romance; for once he devoted himself to the reality of contemporary life, even though the daring departure into realism was thinly veiled by the introduction of that rather unfortunate allegorical figure of Liberty with her clumsy draperies and badly painted tricolour flag. The top-hat and frock-coat, hitherto considered incompatible with a grand pictorial conception, enter with triumphant defiance into the painter’s art; and they detract nothing from the epic grandeur of this truly historical composition. In many ways “The Barricade” was more daringly unconventional than any of the earlier pictures which had stamped Delacroix as a revolutionary. Yet its success was immediate and final. That the artist was awarded the Cross of the Legion of Honour, was perhaps a recognition of his political sympathies rather than of his artistry. But this time Delacroix found favour with the public and the critics.

At the same Salon was to be seen another of Delacroix’s most striking masterpieces, “The Assassination of the Bishop of Liège,” for which he had found the subject in Sir Walter Scott’s “Quentin Durward,” and which was painted for Louis-Philippe, then Duke of Orleans. It is a marvellously vivid realisation of this terrific scene. “Who would ever have thought that one could paint noise and tumult?” wrote Théophile Gautier in his enthusiastic appreciation of this work. “Movement is all very well, but this little canvas howls, yells, and blasphemes!” The realisation of the wild and sanguinary orgy described by Scott is complete and absolute; and yet, in the long list of Delacroix’s “illustrative” pictures, there is none that is so strictly pictorial in conception and less tied to the letter of the author’s description. It is not so much the detail, the personal action of each participator in the drama, upon which the artist depends to tell this ferocious tale of unbridled passion, but the atmosphere of vague terror, the mysterious gloom of the lofty hall, the flaring flames of the torches, the flashes of brilliant reflections thrown up from the luminous centre provided by the white tablecloth, of the importance of which Delacroix was well aware when he said one evening to his friend Villot: “To-morrow I shall attack that cursed tablecloth which will be my Austerlitz or my Waterloo.” It was his Austerlitz.

PLATE V. — THE BRIDE OF ABYDOS

(In the Louvre)

A great reader of English literature, Delacroix found the inspiration for many remarkable paintings in the works of Byron, who was one of the idols of the French Romanticists. As was his wont, Delacroix produced several versions of this subject, which shows Zuleika trying to prevent Selim from giving the signal to his comrades. A smaller variant, painted like the Louvre picture in 1843, and measuring only 14 in. by 10 in., realised the high price of £1282 at public auction in 1874.

PLATE V. — THE BRIDE OF ABYDOS

“The Assassination of the Bishop of Liège” was painted in 1829, the same year to which we owe that superbly handled and strangely fascinating auto-portrait of the artist at the Louvre, which he left to his faithful servant, Jenny le Guillou, on condition that she should give it to the Louvre on the day when the Orleans family were to gain once more possession of the throne. This event did not come to pass, but the picture nevertheless reached its final destination by gift of Mme. Durieu in 1872. Delacroix’s strangely fascinating personality is completely revealed in this masterpiece of artistic auto-biography. In every feature it recalls that famous description of the master given by Baudelaire in his series of critical essays, “L’Art Romantique”: —

“He was all energy, but energy derived from the nerves and the will; for, physically, he was frail and delicate. The tiger, watching its prey, has less light in its eyes and has less impatient quivering in its muscles, than could be perceived in our great painter when with his whole soul he flung himself on an idea or endeavoured to seize a dream. The very physical character of his physiognomy, his Peruvian or Malay complexion; his eyes which were large and black but had narrowed owing to the habit of half closing them when fixing an object, and seemed to test the light; his abundant and glossy hair; his obstinate forehead; his tight-drawn lips to which the perpetual tension of the will had given a cruel expression — in a word, his whole person suggested the thought of an exotic origin.”

It is interesting to note how completely this vivid description of the mature man tallies not only with the painted portrait of Delacroix at the age of thirty-one, but with another description of the adolescent, left by his college friend, Philarète Chasle, who speaks of him as “a lad, with olive-hued forehead, flashing eyes, a mobile face with prematurely sunken cheeks, abundant wavy black hair, betraying southern origin.”