Although travel on roads and canals was already well established, from the 1830s onwards railways in Britain revolutionized the movement of people and freight. They also changed the ways that people spent their leisure time. From day trips to holidays, the railways enabled mass transport over much greater distances than had been previously travelled and at greater speed, too.

Suddenly, ordinary people could access all parts of the country and subsequently the world, if they desired. The introduction of the railways brought an impact on people’s lives that was akin to the mass production of the motor car and the evolution of the budget airline.

The word holiday is derived from the term ‘Holy Day’, and comes from the demarcation of certain days within the christian calendar as feast days. These days would have been documented in the Book of Hours, which detailed the division of the days and the year according to a monastical lifestyle. The book was available to lay people as well, so holy days would have affected the whole community.

The word vacation, derived from the Latin ‘to leave’, gained much of its meaning for a break from work during the Middle Ages. The Inns of Court in London have a yearly calendar that is divided into terms and vacations. To this day, lawyers still process from the temple over to Westminster Abbey to attend the yearly ceremony that signifies the commencement of the first term. When the lawyers are not in residence, they are said to be ‘on vacation’. This vernacular of the law courts was carried over to universities.

However, the more modern perception of a holiday or a vacation, certainly as far as the masses were concerned, was forged in the age of steam. The idea of ‘leisure time’ very much originated in the nineteenth century. With the exception of religious pilgrimages, which were accessible to many people across society, ‘holidays’ had long been the preserve of the rich alone.

Having said that, the concept of ‘tourism’ seems to have been around almost as long as mankind has been civilized. Early forms of travel that might be considered tourism often focused on health. There is a belief that, during the Bronze Age, the site of Stonehenge in Wiltshire attracted people from across Europe in search of cures for a variety of ailments. Similarly, the Romans established many baths used for ritualistic cleansing at the sites of both inland and coastal mineral springs. Those who were sufficiently wealthy could travel to these locations and, over time, many of these spas – such as Baiae in southern Italy – essentially became holiday destinations.

Although Roman baths had been created in ancient Britain, it was in the 1600s that the tradition of medicinal bathing was revived. Thomas Guidott established a medical practice in Bath, Somerset, in 1668, publishing papers discussing the healing properties of the water. Many spa towns were established across Britain as people increasingly began to travel and visit. There is even a town named ‘Spa’ in Belgium, which offers the bountiful iron-rich waters after which spa towns are named.

In the mid-seventeenth century, the Grand Tour also became very popular. The idea behind this novel holiday concept was that wealthy young men of social standing should embark upon an extended continental journey lasting for months, if not years. The Grand Tour was generally conducted in western Europe, although some intrepid travellers ventured further afield. The aim of the tour was to experience the roots of civilization; to gain an education while honing language skills and making social connections; and to collect unique pieces of art and furniture with which to feather a nest and further a reputation in society back home. The Grand Tour became a rite of passage and perhaps even a little formulaic, rather like a modern university ‘gap’ year. It is embossed upon the national consciousness and became something to aspire to for many rich young men over many decades.

With the advent of steam power, the world became a smaller place. Travel became cheaper and easier and there was a host of willing participants all wanting to experience grand tours of their own. Trade routes and military duties had seen people across the social spectrum travel to quite exotic locations, but not for the purposes of leisure. Now all that was about to change forever.

Meanwhile, in the worlds of agriculture and industry, steam was making just as much of a mark. Steam saves labour, in as much as it can do the work of many men. Steam engines deployed in agriculture meant that fewer people were needed to work on farms, so increasingly rural workers travelled to the cities to find work instead. Much of that work was to be found in factories powered by steam. The agricultural year is continuous and hard work but there is an ebb and flow to the work. Sunlight governs working hours and the seasons dictate the pace of labour. Contrarily, industrial steam power is relentless and continuous. So long as someone is feeding an engine coal and water, it never stops. The immense shift from rural to industrial ways of working that steam power caused changed the pace of people’s lives. In turn, this meant that relatively well-paid factory workers – especially in the industrial north – would come to feel that they needed a break. It is generally accepted that the United Kingdom was the first European country to actively promote leisure time to an increasingly industrial population. This was a population that both needed a break and had an income that could be spent on railway transport.

EVENTS

The railways enabled a greater number of people to take part in a wide range of events, from music concerts to sporting spectacles. They represented a good way of moving a large number of people a long distance in a short space of time, meaning that a big audience for a single event could easily be assembled and dispersed within a single day. Perhaps the most famous event of the Victorian period was the Great Exhibition, which was held in Hyde Park in 1851.

Following two decades of political unrest in Europe, the Great Exhibition was a display of ‘the works of industry of all nations’, although primarily it promoted Britain as an industrial world leader. The project was conceived and approved a mere nine months prior to its opening. The majority of the exhibition was housed in the great Crystal Palace, a giant greenhouse structure of glass ceilings and walls. The nature of the structure negated the need for lighting and meant that fully grown trees could be cultivated within the building. This impressive feature was intended to demonstrate Victorian man’s conquering of nature.

The exhibition ran from 1 May until 11 October, when the structure was dismantled and relocated to Sydenham in South London (an area that was subsequently renamed Crystal Palace). During those five short months the Crystal Palace welcomed some six million visitors – a number equivalent to a third of the population of Britain. Tickets were sold to anyone who could pay. The most popular was that costing one shilling (equivalent to five pounds in today’s money), eagerly purchased in volume by the emerging industrial classes. The revenue that was generated above the cost of the exhibition was used to create the Victoria and Albert Museum, the Science Museum and the Natural History Museum at a site to the south of Hyde Park. Some of the money was also used to fund further industrial research.

The exhibition itself included diamonds, minerals, machines, utensils, farm equipment, guns, locks, textiles – pretty much everything under the sun. To accommodate the visitors, the first public flushing toilets were designed and installed by George Jennings. They cost a penny to use, giving rise to the phrase ‘spend a penny’, and Jennings convinced the organizers and park authorities to allow him to leave the toilets in situ after the exhibition closed. It was a wise commercial decision: the toilets went on to generate £1,000 a year in revenue.

When the Crystal Palace was moved to south London and reopened in 1854, it was enlarged and reconfigured. The cost of the move, together with the alterations, saddled the company with a financial burden it never repaid. The chosen permanent location at Penge Common was in part lobbied by representatives of the London, Brighton and South Coast railway. Due to the popularity of the Great Exhibition, the railways would be well aware of the revenue that they could earn from visitors to the new site. Two railway stations were opened to serve the new location; Crystal Palace High Level and Crystal Palace Low Level. The new permanent exhibition space was intended to be a People’s Palace.

The new exhibition housed a host of both permanent and temporary exhibits and offered space for musical concerts and circuses. People from all walks of life could now enjoy what had once only been available to those with money. In 1859, to mark the centenary of the death of the composer George Handel, a commemorative performance of a selection of his music was staged at the Crystal Palace. These Handel festivals became a regular event, being staged every three years until they finally fell out of fashion in 1926.

The performances were colossal and only made possible by the existence of the railways. Audiences regularly exceeded 80,000, with 87,784 people attending in 1883. The first orchestra consisted of 460 players accompanied by a 2,700 strong chorus – but later choruses featured as many as 4,000 performers. The participation of the railways was openly acknowledged – even celebrated – as part of the spectacle, with a mention in the 1862 programme. It was estimated by the Musical Times that for the first concert in 1859, 12,000 people an hour arrived by train. That is 1,000 people every five minutes.

A recording of a Handel festival was made at the Crystal Palace by one Colonel George Gouraud, who worked as Thomas Edison’s sales agent in Europe. This he did using Edison’s recently perfected phonograph. Placing the device 100 yards away, Gouraud succeeded in recording the chorus of 4,000 voices. This was one of the earliest recordings of music and voice ever made. Sadly, unlike the recording, the Crystal Palace did not survive. It was consumed by fire in 1936, despite the best efforts of 89 fire engines and 400 fire fighters. Over 100,000 people came to watch the final spectacle of the palace burning down.

The Great Exhibition of 1851 focused on all aspects of industry. In 1857, Manchester held an art treasures exhibition, displaying over 16,000 works of art. Similar in conception to the Great Exhibition, it ran from May to October, was housed in a building of cast iron and cast plate glass and attracted a great number of visitors. The temporary exhibition house was erected on a three-acre site at Old Trafford, an area of Manchester that had previously been leased to the city’s cricket club. The club moved to the meadows of the de Trafford estate, where Old Trafford cricket ground still stands today.

The exhibition was served by the Manchester, South Junction and Altrincham Railway, which built a station named after the exhibition. The station is now the Old Trafford Tram Stop. The exhibition performed quite well commercially, making a small profit, but the railway did much better financially. Manchester had been made a city in 1853 and the art treasures exhibition announced its arrival on the world stage. It is still thought to be the largest exhibition of art ever held.

After the exhibition closed, the railway station continued to serve the cricket ground on match days. Old Trafford station serves as a reminder of the impact that the railways had on spectator sports. Old Trafford was the second venue to host test cricket in the United Kingdom. The first was the Oval in Kennington in London and not, as you might expect, the home of cricket, Lord’s, which is situated north of the river.

The Oval had been a market garden owned by the duchy of Cornwall, but a lease was granted for the use of the site as a cricket ground. At the start of the nineteenth century, the piece of land in question would have been a relatively rural setting; however, by the close of the century it was a little island in the middle of a great industrial sprawl. That part of London almost remains a monument to the Victorian rail network, with lines criss-crossing each other as they spread out from Victoria and Waterloo. Then they funnel through Britain’s busiest railway station, Clapham Junction, which was built in 1863 on an area of land that had previously seen the agricultural cultivation of lavender (hence the name ‘Lavender Hill’).

The Oval was well suited to facilitate the arrival of the 20,000 spectators who came to see the first match of the first tour of England by any foreign side in 1868. The tourists were the Australian aboriginal cricket team, which played 47 matches in total across England, winning 14, losing 14 and drawing 19. They garnered the respect of the English players and introduced Britain to a wealth of culture. One English cricketer managed to narrowly win a cricket ball throwing competition against the aborigines with a 118-yard throw. He was the 20-year-old emerging talent, W. G. Grace.

The Oval – which is recognized as having the first floodlights of any sporting arena, in the form of gas lamps installed in 1889 – also witnessed the birth of the cricket competition known as the Ashes. What is now referred to as ‘test cricket’ had its origins in England’s 1876–7 tour of New Zealand and Australia. However, it was a visit to England by Australia that saw the competition become immortalized. On average, it took 48 days to sail between the antipodes of Australia and the United Kingdom. Subsequently, the tourist team seldom consisted of a full compliment, as many of the best players could not be absent from work for so long. Perhaps the editor had that in mind when the Sporting Times published their mock obituary of English cricket, with a footnote stating ‘the body will be cremated and the ashes taken to Australia’.

When England returned to Australia, the press – which had enjoyed increased circulations as a direct result of the railways – latched on to these mythical ashes and the statements being made that England would recover them. It took a number of years for the term to become fully ensconced in the lingua franca of cricket, but it is now one of the most famous sporting competitions in the world.

Like cricket, football owes much of its popularity to the railways. The football league was established in 1889 and the railways allowed spectators to travel both to home and away games. As the league grew and more teams became established, sites for grounds were often chosen based on their proximity to a railway. For example, Manchester United moved to Old Trafford in 1910, mainly to take advantage of the railway station that already served the cricket ground.

The London club Arsenal picked its former home at Highbury due to the proximity to Gillespie Road tube station; the ground of Tottenham Hotspur was deliberately situated close to White Hart Lane station; Chelsea picked a site near Waltham Green; and Wembley, which had been built for the British Empire Exhibition in 1924, was placed on a site with excellent rail links. The idea behind the British Empire Exhibition was that it should feature a number of sites all linked by a circular railway, of which Wembley was one. The exhibition opened in 1923, just four days before the first event it was scheduled to host, the FA cup final. In the 51 years that the final had been staged, including eight replays, it was usually held in London. Two prominent venues for the event had been the Oval between 1874 and 1892 and the Crystal Palace between 1895 and 1914. It did not take place during the First World War and resumed in the 1919–1920 season.

Wembley stadium had an official capacity of 127,000, but the 1923 FA cup final was unticketed. This odd state of affairs was compounded by the organizers, who underestimated the number of fans who could turn up, due to the existence of the railways. There are no official figures available, but it is thought that the stadium was filled to at least double if not triple its official capacity (there were also a further 60,000 fans locked outside, to whom gate money had to be refunded). With many fans spilling out onto and almost covering the pitch, the match looked unlikely to take place, until mounted police cleared the playing area. The 1923 FA cup final is known to this day as the ‘White Horse’ final, due to the presence of the police horses that helped to clear the pitch prior to play commencing.

Of the nine police horses that were involved, only one was in fact white – or ‘grey’, to use the correct equine terminology. Constable George Scorey and his white horse Billy helped push back the crowds, along with eight other mounted officers. However, due to Billy’s distinctive colour, he stood out in the black and white photos of the event. As a result of the overcrowding, the match took place 45 minutes late. The bridge outside Wembley stadium was subsequently named in Billy’s honour as ‘White Horse Bridge’.

Although the 1923 FA cup final’s unofficial attendance is probably the highest of any stadium-based sporting event ever, it does not compare to the crowds that regularly attended horse racing events. Cricket, football and boxing all benefited from increased attendances as a result of the railways. However, horse racing was already enormously popular and attracted huge local crowds. The railways just made them bigger. Perhaps part of the appeal of horse racing was that bets could be placed. The gaming act of 1845 meant that the only bets that could legally be placed were with turf accountants at the race tracks. Special excursion trains brought vast numbers of people to race meets across the country. Just before the Second World War, the amount of money being gambled on horse racing during the year was half a billion pounds. Bookies were legalized in 1961 by Harold Macmillan’s government, perhaps as an attempt to collect the tax revenue.

LONDON’S BURIAL CRISIS

As the old saying goes, ‘only two things are certain in life; death and taxes’. Throughout history, London has had a problem with death, or more accurately, what to do with the dead. Initially, those who died in the city were buried in church graveyards, but these became very crowded very quickly. The solution was more graveyards.

St George’s Gardens in Bloomsbury is the site of the first Anglican burial ground that is set apart from a church. Opened in 1713, the park was originally comprised of two graveyards serving two churches – St George the Martyr on Queen’s Street and St George’s in Bloomsbury. The boundary between the two graveyards can be seen today, demarcated by a series of stones. However, St George’s also ultimately became overcrowded.

The population of London recorded by the census of 1801 was under one million. The population of London in 1851 was just under 2.5 million. The amount of people dying in London was increasing exponentially, but the amount of space given over to graveyards was relatively unchanged. It was almost impossible to dig a fresh grave without cutting through existing graves. To make matters worse, the sheer number of corpses was beginning to pollute the water supply. From 1848 to 1849, there was a cholera epidemic in London and the bodies began quite literally to pile up. The system was totally overwhelmed, resulting in a crisis. In 1851, London’s graveyards were closed to new internments. Something had to be done.

Inspired by Paris, between 1832 and 1842 London had embarked on creating seven large cemeteries outside the city limits. Now called the ‘Magnificent Seven’ – a term coined by the architectural historian Hugh Meller after the film of the same name – there was a worry that without a better solution these graveyards would also become overwhelmed. However, Richard Broun and Richard Sprye proposed using the railways as a means of transporting the deceased from central London to a large site well beyond the projected growth of the city in the years to come.

In 1852, the London Necropolis and National Mausoleum Company was established, following an act of Parliament, and on 7 November 1854 the first funeral train left London. The company, which simply became the London Necropolis Company in 1927, had a terminus station near Waterloo and another terminus station at Brookwood in Surrey, where it established what is still the UK’s largest cemetery.

The plan was to run trains early in the morning and late at night, carrying the deceased along with their funeral party to the cemetery. The initial idea of moving the body and the mourners separately had been dismissed. The LNC anticipated moving tens of thousands of bodies a year, but this projection was never fulfilled. The LNC did, however, help relocate a lot of remains from existing London cemeteries. It was during the Victorian period that St George’s graveyards in Bloomsbury were redesigned as gardens with the idea of creating an outdoor sitting room.

One train a day began running from the London Necropolis railway station to the Brookwood cemetery station. It used the London and South Western Railway line, which was subsequently linked onto the LNC’s own branch lines at each end. The coffins and mourners were segmented in upper or standard class. Upon arrival at the cemetery, the coffins were unloaded either at the north station for non-conformists, or the south station for Anglicans. There were also designated rooms for each class of mourner. The initial design of the cemetery branch line meant that the engine would be at the wrong end of the train for the return trip. Therefore, near the entrance to the graveyard, the carriages were uncoupled and then pulled through the cemetery by a team of black horses.

The LSWR were quite worried that the idea of their locomotives pulling dead bodies might put off their living customers, so they bought steam engines specifically to pull the LNC trains. They also eventually provided a free lunch for their train crews (as long as only one beer was consumed by each man), after complaints that some train drivers became so drunk while waiting at the cemetery’s licensed refreshment rooms that they were unable to drive the trains back.

The service ran daily until 1900, after which time it ran as required. The LNC trains stopped running in 1941 and the LNC railway ceased to operate altogether directly after the Second World War. The London Necropolis station had been destroyed in the blitz; the cemetery branch line needed the sleepers to be constantly replaced as the poor ground conditions accelerated their decay; and much of the rolling stock had also been lost in the war. When British Railways was formed in 1947, funeral trains went into steep decline. The last funeral train carried Lord Mountbatten in 1979, and in 1988 British Rail formally ceased carrying coffins altogether.

FAIRS AND MARKETS

Thanks to steam and the network of railways, big events and day trips out became a part of many people’s everyday lives – but it took time. Today, most people take a two-day weekend for granted, but the majority of Victorian working class people only had one day off – the Sabbath. This caused its own distinct set of problems.

The company that was initially set up to run the Crystal Palace when it first relocated did not open the venue on Sundays. This policy was in line with the Lord’s Day Observance Society’s view that people, in this case staff at the palace, should not have to work on the Sabbath. However, starting in 1861, eventually the Crystal Palace began opening on a Sunday – and immediately enjoyed as many as 40,000 visitors in a day.

As society developed, so did social reform. Good Friday and Christmas Day had always been days of rest, but many of the other feast days associated with the religious calendar no longer applied to the working classes. The Bank of England reduced the number of saints’ days it observed from thirty-three to four in 1834 (which included Good Friday and Christmas Day).

One banker who had a strong interest in reducing working hours for the working classes and the implementation of official holidays was John Lubbock. In 1871, he was instrumental in passing the Bank Holidays Act, while he was serving his first term as a Liberal MP. The days that applied to England, Wales and Ireland were Easter Monday, Whit Monday, the first Monday in August and St Stephen’s Day (Boxing Day). The bank holidays were very popular and were initially referred to as ‘St Lubbock days’.

Saints’ days had played an important part in the British calendar since the Roman period. Many of them were associated with fairs or markets. Fairs played an important role in trade, with many being based upon a particular type of livestock. From the Middle Ages onwards, fairs and markets began to become established, as towns and villages were created.

Fairs are certainly known to have existed during the Roman period, when they were considered holidays. Markets and fairs crop up usually in association with a church and many were granted a royal charter. Chartered fairs, as they were known, reached their zenith in the thirteenth century and were an important outlet for trade and leisure in a community. When a fair or market was held, visitors would come from far and wide and the whole operation had to be policed.

Powers were granted to the fairs, so that courts could be held to enforce order and administer justice. These courts were known as ‘piepowder courts’, which directly translates as ‘dusty feet courts’, as a term applied to travellers who walked several miles to reach the fair. The last known piepowder court to be held was at the end of the nineteenth century in Hemel Hempstead, Hertfordshire, and the last active piepowder court was held at the Stag and Hounds public house on Market Street in Bristol. Although the court had not been held since 1870, it was officially abolished with the courts act in 1971.

The number of fairs diminished after the thirteenth century, as the number of markets settled down. However, the remaining fairs played an important role in agriculture, as farmers and drovers moved livestock from hillside to fair along well-established drove roads. As the railways were developed and Britain became industrialized, many of the smaller fairs and markets ceased to exist. Livestock was primarily moved long distance by railway, but the larger markets flourished, such as Smithfields in London.

In certain places, fairs took on new life with industrialization. Famously, Glasgow fair has been held on the last fortnight in July since the twelfth century. Originally a livestock market focusing on the sale of horses and cattle and held at Glasgow cathedral, from the nineteenth century onwards it has been held at Glasgow Green and has become a beacon for travelling showmen. Incidentally, it has been stated that it was while walking in Glasgow Green that James Watt thought up his idea of a separate condenser and thereby made the Newcomen engine far more efficient and considerably more practical.

As the Glasgow fair was a holiday that was already well established in the fabric of the community, the factories in Glasgow respected fair Friday and shut down, to allow the workers to go to the celebrations at Glasgow Green. Fairs throughout history would have attracted travelling showmen. With the invention of steam, the fairs became mechanized and many of the showmen brought engines. Showmen engines were usually characterized by their bright colours and long canopies, which covered the whole engine. They had long or extendable chimneys to get the draw needed and to protect the punters from hot smuts. The engines were used to provide power for electric lighting and to operate rides.

As the steam power took hold, the rides took off. They became progressively bigger and would have changed the feel of the fairs from the agricultural affairs they once were to the funfairs and carnivals we know today. A ‘carnival’ was specifically a festival that happened directly before lent but, certainly in the UK, this has also become a term that is used to describe the annual town celebrations that were once fairs. One of the most enduring and popular rides at a fair is the carousel. It was invented by one Frederick Savage, who made the move from agricultural machine builder to fairground ride innovator. The name ‘carousel’ was derived from a complex military dressage manoeuvre that garnered popularity in medieval jousting arenas.

Shortly after seeing a mechanical steam-powered roundabout at the Aylesham fair in Norfolk, Frederick Savage began designing his fairground rides. By the turn of the century, he had perfected his carousel with lights, an organ and horses that galloped up and down on poles. These original carousels are things of beauty. Strangely, there has long been a tradition that British carousels rotate clockwise, whereas European and American carousels rotate anti-clockwise.

The practice of shutting the factories in Glasgow for the fair was not unique to that city. Many industrialized cities had similar traditions. There are a number of documented instances of factory fortnights or what are also termed ‘wake weeks’. My mum can remember the factories all closing down at the same time when she was a girl growing up in Glasgow. She also remembers that the nearby cities would also shut their factories, but the dates would be staggered so as not to clash with those of Glasgow or other nearby industrial centres.

The roots of these factory fortnights lay both in the religious fairs and the Scottish tradition of the trades fortnight, when each trade takes its summer holiday. The usually unpaid leave of a wake week allowed the factories to undertake any maintenance jobs that could not be done while the factory was in steam, and it also allowed the factory workers to go on holiday. With the rail network in place, a holiday could be taken effectively anywhere, but the most popular destinations were the seaside resorts.

HOLIDAYS

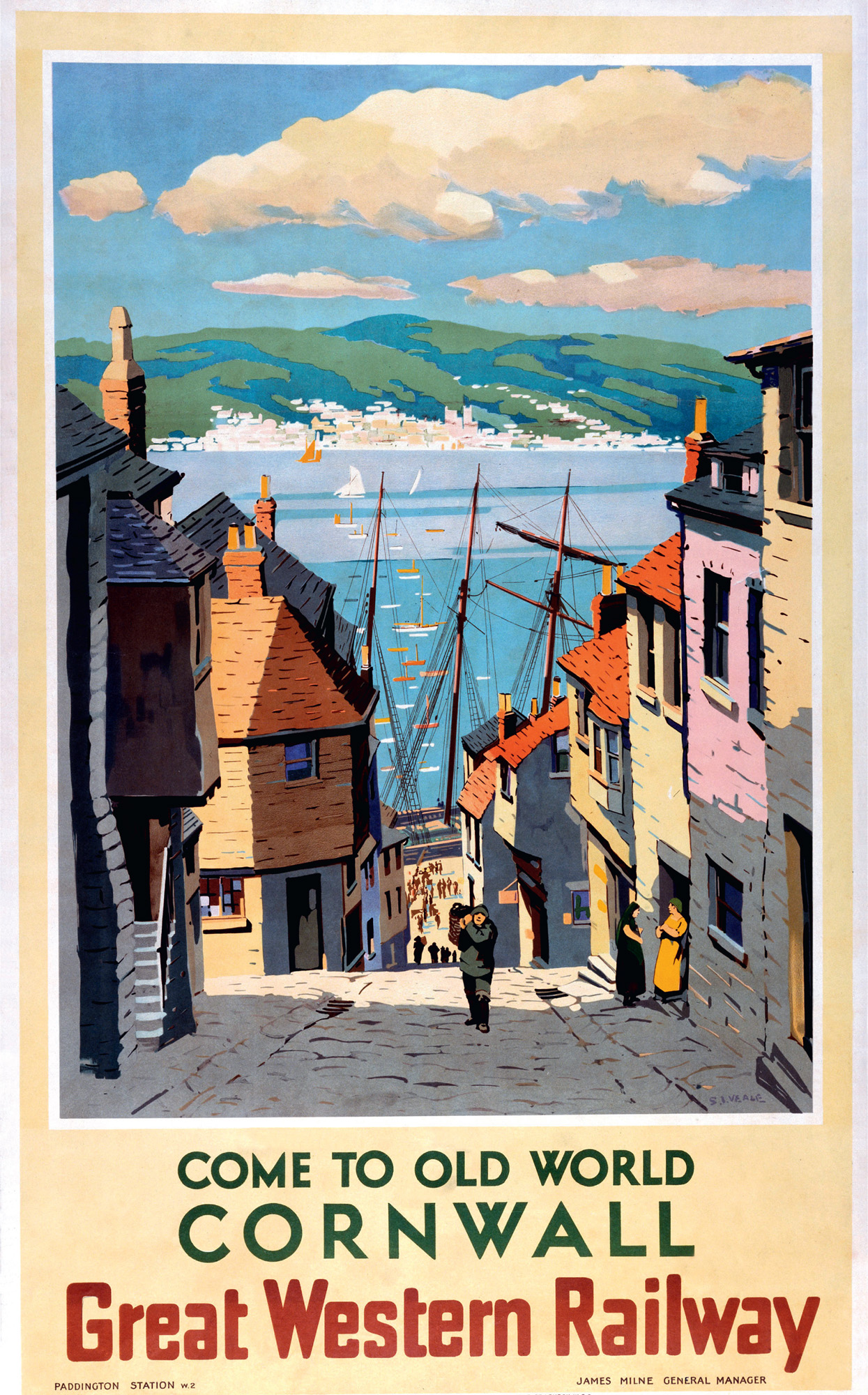

The idea that the sea had restorative properties was a long and widely held belief. However, prior to the happy combination of both free time and the new access provided by the railways, a trip to the seaside had largely been the preserve of the rich. During the down time of a wake week, people would often travel to the seaside either as a day trip or later for an extended period. It was not until the Holiday Pay Act of 1938, following lobbying since the First World War, that wages were paid to the working classes during a vacation of the factory. Prior to that, savings clubs were set up to fund the excursions.

The landscapes of many of Britain’s seaside towns have developed as a direct result of catering for the mass influx of tourists. Those settlements on the coast that have natural or manmade harbours that permit boats to dock were less affected, as they already had a rich culture of fishing and therefore an infrastructure built around an industry. However, many of Britain’s beautiful beaches became beacons for visitors, and much of what can be seen in relation to a beach resort today was built in the Victorian period.

WILLIAM WORDSWORTH (1770–1850)

The poet William Wordsworth was not a fan of railways. When a proposal was made to extend the line to his beloved Lake Windermere, he fired off an extremely huffy letter of opposition to the Morning Post in 1844 with an even more disgruntled follow-up shortly after. His career as a poet had been spent extolling the beauty of the Lake District’s wild places, in describing the solace such landscapes could bring. He strove, along with others, to change the public view of unproductive land from ‘waste’ to ‘healing nature’. He wrote of the power of the wild natural world to inspire, to transport the human mind to a higher, more spiritual state. He wished people to follow his lead and head outside in search of the ‘sublime’. But not, it transpires, too many people, or the wrong sort of people.

‘We should have the whole of Lancashire, and no small part of Yorkshire, pouring in upon us to meet the men of Durham, and the borders from Cumberland and Northumberland. Alas, alas, if the lakes are to pay this penalty for their own attractions!

Picturesque and romantic scenery is so far from being intuitive, that it can only be produced by a slow and gradual process of culture; and ... as a consequence, that the humbler ranks of society are not, and cannot be, in a state to gain material benefit from a more speedy access than they now have to this beautiful region.’

Wordsworth’s vision of the Lake District was one that he intended only for the select few.

However, the great British public read his poetry and took it to heart – and then they just as firmly ignored his letters about the unstoppable spread of the railways. Taking the train to outdoor beauty spots and making holidays from a mixture of train rides and walks, quickly and quietly became a nationwide habit – one enjoyed by all but the very poorest levels of society.

Blackpool is the most famous example of the seaside resort towns that boomed because of the railways. Trains from Preston brought wave after wave of tourists, primarily from Lancashire, along a branch line built in 1846. The staggering of mill and factory closures over the summer meant that Blackpool could both handle the tourists and was assured of a season. It had originally been a location for ‘taking the cure’, so some hotels did exist as well as a road to the resort. However, the trains brought huge numbers of tourists and that created a market that enterprising business people jumped upon. No longer would a dip in the sea and a game of bowls suffice.

Preston was the first location outside of London to have gas street lighting in 1825, and piped water was installed in 1864. Blackpool received gas lighting in 1852. The street lighting was upgraded to electric street lighting in 1879, a year after Paris and London had seen some electric street lights. These lights along the promenade were associated with a certain amount of pageantry and spectacle, which later evolved into the world-famous Blackpool illuminations. In 1885, one of the world’s first practical electric tramways was installed and ran with an unbroken history until 2012, when the rolling stock was upgraded. The old trams still run occasionally, and are some of the only double-decker trams in the world.

Blackpool also saw three piers constructed, the first being what is now north pier in 1863, central pier in 1868 and finally south pier in 1893, as the linear town of Blackpool spread further than the area known as the ‘Golden Mile’. The Victorians constructed a lot of piers at seaside towns, but Blackpool is the only one to have three. Their design is in part due to the fact that when the tide goes out, often the promenade is a long way from the sea. Southend at the mouth of the river Thames has the longest pier in the world. It is 1.34 miles long, which reflects the fact that the sea goes out over a mile at low tide, exposing unattractive mud flats. If daytrippers are only visiting for a short time, a pier ensures good access to the sea. It also allows boats such as paddle steamers to dock without the need for a harbour, and bring visitors to the towns via the sea.

SEEING THE SIGHTS

If you have ever read Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice, you will know that by 1813 when the book was published, there was already a well established tourist tradition of visiting stately homes and picturesque countryside. Elizabeth Bennet, the heroine of the book, is taken on holiday by her aunt and uncle in their carriage, stopping at country inns along the way. They pay a visit to Pemberley, the grand home of Mr Darcy, and are shown around by the housekeeper. It was not an unusual thing to do – anyone who was well dressed and owned or could hire a carriage was free to make a similar visit by appointment to most of the great houses of Britain. However, getting there did limit the experience to the very top rungs of society. The railways were to change all that, allowing many more people the opportunity to partake of these upper-class pleasures. Up and down the country, wherever a line ran close enough, housekeepers began to find themselves inundated with requests. Regular hours for visiting began to be introduced and dedicated guides rather than the busy housekeeper were employed to look after this new flood of visitors.

Outdoor sites proved even more accessible. Consider Corfe Castle in Dorset, for example. At the end of the eighteenth century, it was attracting a trickle of romanticaly minded, well-heeled visitors – people like William Turner, who painted a watercolour of the scene in 1793, dwelling on the play of light across its crumbling ivy-clad walls. It was just the sort of place that Elizabeth Bennet would have visited had her holiday been in Dorset rather than Derbyshire and by 1829 sported its own guide book, A Historical and Architectural Description of Corfe Castle By a Near Neighbour, which was full of historical colour and atmosphere. In 1885, a new branchline opened from Wareham to Swanage, passing right alongside the castle with a station at its foot. The latest guidebook published just eighteen months earlier – The History and Description of Corfe Castle, by Thomas Bond – began ‘The silence of this gloomy fortress has rarely been disturbed save by the wail of the captive in his dungeon, or the clank of the warder, as he paced his rounds within the battlements.’ It was a rather serious booklet in the main, outlining the author Thomas Bond’s ‘diggings’ ( archaeology of a sort) and historical researches among the records, but he could not resist the gothic, the romantic and the emotive. Such sites were meant to be enjoyed on several levels and ever-increasing numbers of people arrived by rail to walk, to admire the view, to dream romantic dreams, to enjoy the puzzle of working out the architecture and to feel a connection with the past. The low-cost nature of such sights was an additional draw.

By 1935, the Southern Railway was using an image of Corfe Castle with the railway running around its base upon posters to advertise their services. Visiting historic monuments and scenic countryside generated good passenger income.

Piers for the loading and unloading of cargo have been around for a long time, but in the nineteenth century pleasure piers were an entirely new thing. Blackpool north pier is the longest of the three piers and was originally only intended as a promenade. It was built near to the first, and now only, railway station. As the town grew, central pier was built five years after the construction of Blackpool Hounds Hill railway station (later Blackpool central) which at its peak had 14 platforms and was the station with the most platforms to close in the 1964 revision of the railways. Both piers offered steamboat excursions, but central pier focused on fun – mainly in the form of dancing – rather than the more genteel pursuits offered by north pier. When south pier was built, north and central piers were competing for that ‘fun’ tourist market. South pier was commissioned when people began going further down to south shore, after a carousel was installed near the sand dunes. It was wider and shorter than its predecessors, had 36 shops, a bandstand, an ice cream parlour and a photo booth. It is also where the popular twentieth century entertainer Harry Corbett bought the famous television show glove puppet that was known as Sooty.

Blackpool’s physical attractions also include: the Winter Gardens, built in 1878; the pleasure beach, first started in 1896 opposite the tram terminus, but which came into its own in the early twentieth century; and, most famously, the Blackpool tower, which opened in 1894. Designed to look like the Eiffel Tower, it stands at 158 metres tall and is a monument to the evolution and development of coastal towns due to the railways.

Holidaymakers and daytrippers from Glasgow often found themselves in the nearby coastal resort of Millport. To get there, the tourists would generally travel down the Clyde on a paddle steamer. Millport still sees the last operational sea-going passenger paddle steamer, the Waverley, visiting the resort and bringing passengers in the summer. The PS Waverley was built in 1946 to replace a previous paddle steamer named Waverley. That ship was built in 1899 and saw service as a minesweeper in the Second World War, before being sunk during the evacuation of Dunkirk in 1940. She was part of the LNER and worked their Firth of Clyde steamer route briefly, before the nationalization of the railways, when she came under control of the railway executive. The notation ‘PS’ stands for ‘paddle steamer’, which is a vessel with a large paddle wheel on the side. ‘SS’ stood for ‘screw steamer’, which is a vessel with a propeller, although SS often just means ‘steam ship’.

It was on the Firth of Clyde in 1812 that Henry Bell’s Comet ran as the first commercially successful steamboat service in Europe. By 1822, there were 50 steamers in operation on the Clyde and by 1900 there were over 300. Steam power on the rivers and more importantly the seas allowed for boat services to be run in much the same vein as the railways. Unlike ships that purely relied on sail, steam-powered vessels could still progress when there was insufficient wind. Although affected by adverse weather, on the whole they could be run on a timetable. The great Victorian engineer Isambard Kingdom Brunel was commissioned as chief engineer to build the Great Western Railway in 1833. He envisioned a steam ship service from Bristol to New York that could effectively be an extension of the railway. In 1836, the Great Western Steam Ship Company was established, and from 1838 until 1846 a regular transatlantic service ensued.

The Great Western Steam Ship Company was affected by the rocky debut of Brunel’s SS Great Britain. Initially intended to be a paddle steamer, Brunel changed the design after seeing the SS Archimedes, the first screw-propelled steam ship. When floated in 1843, the SS Great Britain was the largest vessel on the seas. However, her extended build time and increasing costs had taken their toll on the company. When she ran aground due to navigational error and was feared beyond retrieval, the Great Western Steam Ship Company suspended all sailings and went out of business in 1846.

The SS Great Britain was however saved, and continued in service for several more years as a steam passenger ship with Gibbs, Bright & Co. While in operation as a passenger ship, she ferried the England cricket team on their first tour of Australia in 1861. She was then converted to a sailing ship to carry cargo, in 1882. She is now a museum in dry dock in her home town of Bristol.

Steam ships and railways linking the world are ultimately what ended the existing upper class tradition of the Grand Tour. They also changed it to create something that was cheaper, easier and open to all. Mass tourism was now a realistic option and one man was ready and waiting to make it happen – Thomas Cook.

Thomas Cook is considered to have been the first commercial tour operator. He started by offering day excursions to the temperance society to which he belonged. The excursions were to events including the Great Exhibition in 1851. Excursions that were cheap, popular and conveyed large groups to a single event were pioneered by the Mechanics Institute, which in 1841 organized visits between the Leicester and Nottingham branches. These excursions were many people’s first experience of train travel and moving at speed and were quite the spectacle themselves, with most of the townsfolk waving the trains off.

Cook’s excursions quickly established him as a popular tour operator, and by 1855 he was organizing tours to Europe. Starting with the Paris exhibition, his plan was to offer grand circular tours of Europe and then further afield, as ‘inclusive independent travel’. By the mid-1860s, Cook’s tours were taking in Egypt and America. Thomas Cook was joined by his son John Mason Cook, and in 1871 the company became Thomas Cook & Son, offering round the world tours that took in Japan, China and India.

The company published Cook’s continental timetable, which they continued to print up until 2013. It is now printed by a different company. In 1874 the company began issuing circular cheques, which are now better known by their AmEx branded name of ‘traveller’s cheques’. Thomas Cook & Son established offices around the world and in 1888 they sold three and a quarter million tickets for package holidays.

The tours were relatively expensive and lasted several weeks, but they were a once in a lifetime event and catered very much for the emerging middle classes. While on tour, excursions were offered that took in local culture or activities. The company also published guidebooks for travellers and they sold paraphernalia in their shops that prospective travellers might need, such as luggage and suitable footwear.

As mass travel now became available through the power of steam, certain destinations gained a new clientele. Nice in the south of France near the border with Italy was one such place, adopted by the British as a location to take the winter sun. With money donated by the Reverend Lewis Way, a promenade was built in Nice that was named the Promenade des Anglais. Similarly, in the north of France, Dinard became a very popular destination for summer holidaymakers, and in the late nineteenth century wealthy Britons built large villas along the coast.

The railways facilitated travel across the world and with it came some iconic trains. The Orient Express, the Trans-Siberian railway and the Blue Train are all examples of the grandeur put on offer by many of the world’s railway companies. The Orient Express is perhaps most famous because of the Agatha Christie novel, Murder on the Orient Express. It became a byword for luxury, but in reality it was a rail service that primarily linked Paris with Istanbul. The Blue Train was a luxury overnight express favoured by the wealthy that linked Calais with the French riviera. To link up to these, Southern Railway offered the Golden Arrow, which carried passengers to Dover and onto a luxury boat service to Calais. From there a connection to Paris could be taken, in the form of the equivalent Flèche d’Or.

Holidays were not a reality for all, but a tradition of hop-picking as a working holiday was cultivated by the railways. Beer was an essential drink in places where there was no source of reliable clean water. The boiling of the water, the alcohol and the hops all added to its preservative and sterile characteristics. One place that beer was required was India, but traditional brews did not travel well. The solution was the development of the IPA or Indian Pale Ale, which had both a slightly higher alcohol content and an increased number of hops that contain natural antiseptics.

Hop-picking today is generally mechanized, but before these innovations it was a labour intensive process. At one point hops were grown across the entire country and would have been harvested by seasonal workers to be used by the local breweries. However, as the railways were developed, farming could become specialized and suddenly breweries could get their hops from Kent and their barley from Hampshire, if they so desired. The railways meant that counties that grew large numbers of hops could bring in large numbers of seasonal workers in a process that developed into working holidays for the working classes, especially those from the east end of London. The hops were picked, often using stilts for the large climbing varieties, put into bags while still green, and taken to drying houses. Once dried, the hops were packaged into large sacks known as hop pockets and then transported to the breweries. The sacks were a good six feet long and weighed about 80 kilograms. A few hops go a long way in the brewing process, as they are very pungent and act like a herb in cooking. However, due to the vast quantities of beer being produced and either sold or given as a daily ration to those working in industrial environments, such as metal-producing factories, the demand for hops remained high.

The train remained a leading form of transport for holidays up until the advent of affordable air travel, although at the end of the nineteenth century touring cars were beginning to appear. In 1900, the French tyre manufacturing company Michelin produced a restaurant guide for motorists so that they could determine if a restaurant was worth a detour. The guide was given away for free in France and was intended to boost the demand for cars and subsequently car tyres.

Although the internal combustion engine fuelled by petrol became the primary car propulsion system, there were other forms of car being made, including steam cars. For a short period in history, steam cars represented the pre-eminent car technology. The knowledge that had been gained and refined through the operation of steam engines on the railways meant that the first steam cars had advantages over their internal combustion engine competitors. They were very quiet and their fires consumed most pollutants, so there were fewer emissions. They did not require a crank handle to start them and they could be driven off quickly once they were at operating temperature. Innovations in steam motoring technology saw some steam cars being able to start from cold after forty seconds of the turn of a key. Like the steam locomotives on the railways, steam cars did not require complex transmission systems and so did not need a clutch. Incredibly, for a while, a steam car even held the land speed record.

However, steam cars did have drawbacks – primarily their vast consumption of water. Some cars had facilities to carry extra fuel and water, but when the electric starter motor was introduced along with the production line, both the ease and the cost of petrol cars improved. After the Great War, steam cars started to become museum pieces and collectables for enthusiasts. Like steam locomotives, they are remembered fondly as part of a world that no longer exists.

MEMORABILIA

Due to the pollution that they caused – ‘peasouper’ fogs in London and smog that enveloped many other cities – in the end steam engines were viewed by many as dirty and inefficient. However, steam engines are a marvel, and during their heyday and after their time they have captured the imaginations of many and taken a permanent residence in that world of nostalgia and memorabilia.

The decision taken in 1955 to stop steam engines on the railways actually did not come into effect until the summer of 1968. One year later, in the summer of 1969, what is now known as the Great Dorset Steam Fair was launched. Although its focus is not on the steam engines of the railways but rather on the traction engines used in agriculture and on the roads, it is a demonstration of the British public’s love of steam, with its regular annual visitors numbering as many as 200,000 people.

The idea of preserving steam has been around since the early steam locomotives were gradually being superseded. A proposal for a national railway museum was made in the nineteenth century and the Science Museum inherited an early collection of steam engines that was started by the patent office in the 1860s. Several of the railway companies kept examples of their early innovations on display at stations, but it was hit and miss as to what was preserved and how well it was preserved.

Commander John Baldock began collecting traction engines in the 1940s, as they began to disappear from everyday life. At times, traction engines would be pulled out of hedges where they had been abandoned in favour of new machines, but now they are now worth a lot of money. Baldock’s collection grew and became what is now the Hollycombe steam collection, based near the town of Liphook in Hampshire. It consists of agricultural, fairground and railway machinery, which without museums, enthusiasts and collectors would have faded from life only to exist in art and fleeting glimpses in films.

Railways have always lent themselves well to film and the public imagination. Cinematography started in the 1890s and took off from there. Prior to 1927, films were silent, accompanied by an organist, pianist or even an orchestra. They are a visual medium that can document motion beautifully, so trains have always been a natural fit for the silver screen.

The showing of the world’s first public film at the Grand Café in Paris contained a railway scene. Soon after, the short films of around one minute that could be made with the early technology featured aspects of the railways, such as trains passing or expresses arriving at stations. In the late 1890s, a number of films termed ‘phantom rides’ were made, by strapping the camera to the front of the locomotive and effectively filming the dramatic point of view of the locomotive.

As the cinematic technology progressed, so too did the sophistication of how the trains were used. Strangers on a Train, The Great Locomotive Chase, Paris Express – in all these films, the train was the star. A film made in 1979 called The First Great Train Robbery was based on the book by Michael Crichton, which in turn is based on the actual events of the great gold robbery in 1855. During this great crime, gold en route from London to Paris was stolen and substituted by lead shot, so that the crime would remain undetected until the lead had reached the continent. Crichton’s version contains a theory by the robbers that when exiting the moving train to climb back to the guard’s van, the prevailing forces created by the moving train would help anchor the villains to the train. A nice insight into the Victorian mindset regarding a new technology. It could be argued that, in part, trains helped attract audiences to cinemas, as they were so monumental in society.

Trainspotting is a term that many find offensive and can have a variety of different connotations. What is definite is that with steam locomotives came a fascination of steam engines, most usually amongst small boys. Springburn in Glasgow, Scotland – where my mother grew up – was a rural hamlet at the start of the nineteenth century, as the name might suggest. However, by the end of the nineteenth century, it was an inner city district. It was home to heavy industry associated with the railways, with four railway manufacturing sites. At one time it was producing 25 per cent of the world’s locomotives. Often the locomotives were for domestic usage, but many were for use overseas, and Springburn built some giants. When an engine was completed, it was brought out of the respective works and into the streets for transport on to its intended destination. This was a spectacle not to be missed by the children playing in the streets, especially the boys.

It is perhaps the unique nature of steam engines, their varied personalities and how much they impacted people’s lives that fostered a national obsession with trains. Ian Allan worked in the PR department of Southern Railways at the age of twenty in the offices of Waterloo station. He received various requests by interested members of the public as to the extent of Southern Railway’s rolling stock. Taking the initiative, he published The ABC of Southern Locomotives, which proved so popular that he formed an eponymous publishing company to simultaneously create and promote the hobby of trainspotting.

Trainspotting is still going strong today and is often accompanied by train photography. Many railway enthusiasts also pursue the hobby of creating model railways. The first model railways available were toys from the 1840s. There was no track and they were known as ‘carpet railways’ or ‘Birmingham dribblers’. The locomotive was operated by steam and could run along the floor. A number exploded, so later models had safety valves fitted. Carpet railways were produced by a number of companies and ran on the burning of methylated spirits, which would have been readily available as a source of fuel for lamps. Their wheels could be turned so that the engine would run in a circle without the need for track.

Model railways are serious business. A magazine published in 1898 called Model Engineer provided literature for the emerging hobby and is still published today. The oldest society in Britain for enthusiasts is the Model Railway Club near King’s Cross in London and was established in 1910. There are a number of gauges or scales that are used for modelling and often entire dioramas of specific periods of history of certain railways are recreated. Some scales – such as the 1972 Z scale – mean the locomotives can be held in the palm of the hand, and other scales – such as the live steam 1:8 scale – allow for the creation of an actual ride on the railways.

Model railways are not considered toys, but it was quickly realized that there was a market that stood somewhere between the accurate scaling and recreating of railways and playing with a ‘Birmingham dribbler’. Frank Hornby, who had invented and patented Mechano in 1901 and successfully improved it by 1907, began making train sets in 1920. They were initially clockwork, but the firm that Hornby set up was soon producing electric train sets. They began making models on the 00 gauge in 1938 and since then this has remained Britain’s most popular model gauge.

Steam fairs, museums and model railways are all good sources of information about the era of steam trains, but it is the preserved railways that keep much of our knowledge of Britain’s steam railway heritage alive. Many of Britain’s preserved railways were established shortly after the axe of Dr Beeching fell in the 1960s. This has led to a strange situation in which some railways are close to operating longer as preserved railways than they did originally as commercial railways, and some rolling stock has had a longer working life in the heritage world than it did when it was first built.

There are over 170 preserved heritage railways in the UK and Ireland, focusing on all aspects of Britain’s railways. These include post-steam projects such as the Advanced Passenger Train and the mighty diesels known as the ‘deltics’. Some lines, such as the Ffestiniog railway in northwest Wales, are narrow gauge industrial lines. Ffestiniog grew up around the slate mining industry and cuts through the beautiful Snowdonian landscape. Others are branch lines. The Keighley and Worth Valley railway in West Yorkshire is quite unique in that it is an entire branch line. Most preserved railways tend to be one end of the other of a discontinued branch and often, if they have two parts of a branch line, they have grand plans of linking them up. The only preserved double track mainline railway is the Great Central Railway in Leicestershire. Most steam railways are limited to 25mph, but the Great Central Railway breaks this rule as its trains travel at over 35mph. This is due to their operation of the travelling post office. The leather pouches that contain the mail that are hung off the side of the train or snatched up by the net on the side of the train will only work at between 35mph and 85mph. If the train is travelling more slowly, the mechanism will buckle and become damaged.

Knowledge is lost very quickly after something stops happening. The creation of Britain’s railways changed the world and continues to have a profound effect on our lives. Steam railways facilitated leisure time and gave us the impetus for mass travel. With those systems in place, the airlines took up the baton of package holidays from the mid-1960s onwards, and with the advent of cheap air travel many of the towns that had thrived under the railways, such as Blackpool, began to decline. However, railways still afford us the opportunity of moving quickly across the country and the world. We still use railways for leisure, be it to attend a football match, to listen to bands play in a muddy field in the countryside, or to have a city break.

The innovations and ideas of the nineteenth century still shape our leisure time and many of those railways that closed have found new life as tracks for walkers. One example is the Parkland walk in London, which was the old railway that used to connect Finsbury Park with Alexandria Palace. It is quite evident, due to its location in such an urban area. Other former railway lines are often stumbled upon in the countryside. Mainly firm under foot, generally level and often passing under or over bridges, the telltale signs that a linear lane was once a branch line are all around. Next time you stroll down one, have a think about just how much work went into its creation and just how much the railways forged British society.