5

Do your acquisitions consistently pay off for shareholders?

Was it the best of times or the worst of times? In 2000, CEOs Gerald Levin and Steve Case announced that Case’s America Online would be acquiring Levin’s Time Warner for about US$182 billion in stock and debt. At the time, it was the largest takeover ever. Time’s own Fortune magazine reported on the “widespread confusion about the payoff in this deal.” How should Wall Street evaluate this transaction, the unprecedented acquisition of an old, storied media company by a new, digital one? Veteran journalist Carol Loomis wrote, “The murkiness won’t be dispelled soon. Even at internet speed, it will take some time for the world to judge whether AOL overpaid in offering 1.5 shares of its stock for each Time Warner share, or whether Time Warner sold its impressive assets too cheaply, or whether this is truly a marriage made in heaven.”1

Since then, the union has become the poster child for matches made in Hades. Two of AOL Time Warner’s problems were the dot-com crash and then the corporate-culture clash of analog-content creators and digital-content distributors. Its stock price plummeted, and Levin left the company in 2002. The board approved the diplomatic Richard Parsons to replace him, and Parsons braced shareholders for the turnaround.2 In a few years, he indeed helped turn the company around, dropping AOL from its name and restoring Time Warner to its perch as the world’s most profitable media company.3

Fast-forward to 2007. Parsons’s successor, Jeff Bewkes, was known for his celebrated television dramas (e.g. producing The Sopranos) rather than for corporate drama. His strategy focused on what he considered to be the company’s competitive advantage—its video content—and he started investing more than US$12 billion a year in new program development. He also shed assets that didn’t strengthen the company’s competitive position, such as the remains of AOL, Time Warner’s cable distribution business, and the Time Inc. magazine group. In 2017, Bewkes announced his biggest deal yet: the sale of the whole company to AT&T for US$109 billion. With the June 2018 closing of this new marriage of content and digital distribution, Bewkes has delivered an eye-popping 341% return to shareholders during his time in office, including spin-offs and dividends.4

An age-old M&A question

Our tale of two Time Warner deals brings us to one of the more debated questions within the world of modern finance: on average, have M&As destroyed more value than they have created? Among those who say “M&A activity generally creates shareholder value” are many investment bankers, corporate lawyers, shareholder activists, and other advisors who make their living by advocating and brokering such deals. Those who say “Such deals often fail to create value and can even destroy it” are typically management consultants who sell their postmerger integration services to forestall the predicted destruction. They often say that the main reasons for not delivering sufficient value are overpaying for the deal and missteps in integrating the acquired company. They also will add that management tends to underestimate both deal integration costs and the difficulty in capturing synergies.

To get at an empirical answer, EY reviewed much of the scholarly and not-so-scholarly research on the subject. In one study of 500 publicly traded companies in developed markets, the enterprise value growth rate of serial acquirers—those firms that acquired at least one company a year between 2009 and 2013—was 25% higher than that of firms without acquisitions. These serial acquirers had a 31% higher enterprise value to EBITDA multiple than the nonbuyers.5 Of course, correlation is not causality, and comparing companies that do many deals with those that do fewer doesn’t tell us what might have happened to these acquisitive companies had they not acquired.

Stress testing your M&A activities

Though there may not exist definitive statistical proof of M&A’s value, we have seen the following, time and time again: companies that do not innovate and grow don’t thrive. Instead, they slip into a rapidly accelerating death spiral of market-share erosion, brand devaluation, talent attrition, and cost cutting. This inevitably leads to a further slowdown in top-line growth, a decline in stock price (which of course is largely based on expectations of future growth), and a loss of shareholder confidence. Even those companies considered by many to be the most internally innovative and well run—Microsoft, Disney, and Johnson & Johnson, to name a few—rely to varying degrees upon M&A to fuel their innovation and growth. How could they otherwise develop all of the operational know-how, market access, customer knowledge, intellectual property, and other attributes required to succeed in this rapidly changing world? M&A is a crucial tool for growth and survival.

However, not all M&A is good; in some cases, companies move too quickly. Valeant Pharmaceutical’s rapid attempt to digest more than 50 acquisitions over five years is one example. Likewise, the infamous WorldCom made 65 acquisitions in rapid succession before it imploded. But that type of roll-up strategy tends to be the exception rather than the rule.

If M&A is an essential item on a firm’s Capital Agenda, then the question that board members, CEOs, CFOs, heads of corporate development, and other executive stakeholders should ask themselves is: “How do we manage the upside return and downside risk of each deal?” Put another way, “How do we stress test our M&A—particularly when we are doing many transactions—in order to maximize shareholder value?” We suggest four areas of action:

1. Choose the right deal type for your goals

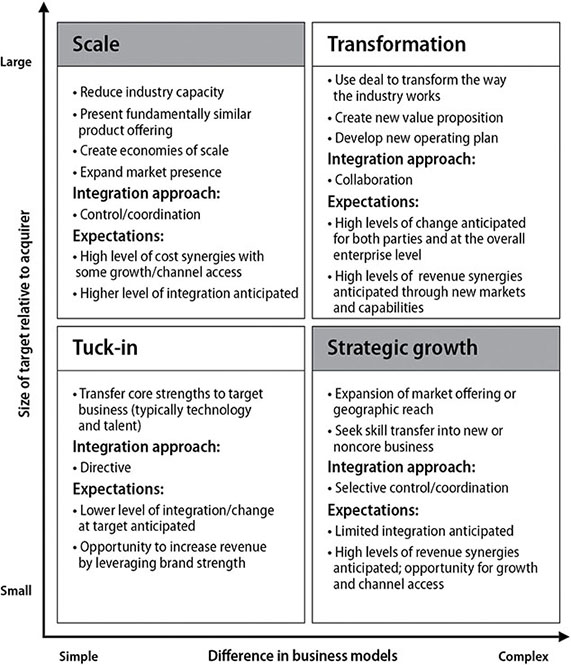

Companies have many reasons to make an acquisition. We categorize these deal types into four quadrants, according to the size of the acquired company relative to the acquirer and the complexity of the business models to be integrated. See Figure 5.1.

- Scale. This is typically a large combination in the same or very similar product or service area. It is intended to increase sales or pricing power in the market and to gain cost synergies. Examples include the Discovery-Scripps acquisition and the Praxair-Linde merger of equals.

- Transformation. These acquisitions are both large enough and strategic enough to transform the company into something new and different. Steve Case and Gerald Levin said of the AOL/Time Warner deal that Time Warner would change from an analog company to a digital one through AOL’s acquisition. Another example would be the Dow/DuPont merger.

- Tuck-in. This is a small to medium-size acquisition (relative to the size of the acquirer) in a space similar to the acquirer’s core business. It fills some gap and leverages the existing base without a dramatic change to the core business. Many transactions in the packaged goods, personal care, and pharmaceutical space fit this category. Estée Lauder’s acquisition spree, including GLAMGLOW, Le Labo, Rodin, Smashbox Beauty Cosmetics, and Too Faced, fall into this category. So does Johnson & Johnson Consumer’s acquisition of NeuWave Medical for its soft tissue microwave ablation capabilities.

- Strategic growth (also known as a bolt-on). This is a small to medium-size acquisition in a new area, or an area different from or adjacent to the core. It is a means of diversifying while leveraging part of the same platform, infrastructure, or skill set. Examples include Microsoft/LinkedIn, Amazon/Whole Foods, and Tyson/Pierre Foods.

Figure 5.1 Categories of deal types

Deals might sometimes fall into more than one of the quadrants. What matters most is that the deal rationale aligns with the integration strategy and architecture.

2. Use objectivity in valuation and business modeling

As we discussed in Chapter 2, using objectivity prevents overpaying and allows you to plot more than one path to risk-adjusted value creation by not relying solely on a specific inorganic path to growth. It’s also important to have a strong stage-gate process that is consistently applied. Investment bankers and others are incentivized to get deals done, so it’s important to counterbalance that view with a risk- adjusted view of the synergies and other valuation assumptions.

3. Conduct thorough due diligence

Due diligence must thoroughly cover all the crucial areas, including the following:

- Financial.

- Tax.

- Legal and environmental.

- Commercial, including such functional areas as information technology (IT), cybersecurity, and manufacturing operations.

- Cultural fit, or the similarities and differences between organizations, especially the potential points of conflict (the review must include a plan for onboarding, socialization, and acclimation).

In our experience, thorough due diligence, with a particular focus on the future, can help remove politics and personalities from the decision process by forcing everyone involved to view the deal through the same lens—namely, one of what the operating model will look like postclose, how long it will take to get there, and what the costs and benefits are. Especially in the dynamic world we live in, due diligence must focus more on the future potential of the target than on its history leading up to the acquisition.

4. Formulate integration strategy and implementation plans, and work to ensure they’re aligned to deal strategy

Too often, executives underappreciate the importance of integration strategy, the difficulty of capturing synergies, and the deterioration of value that comes from moving too slowly. This is why increasingly we see corporate boards asking for the integration playbook or plan as part of the due diligence process, and why integrations are not a one-size-fits-all effort. Rather, the best executives work with their integration leaders to align around a plan, communicate it to others, prioritize resourcing for the plan, and help troubleshoot throughout implementation.

Lessons learned

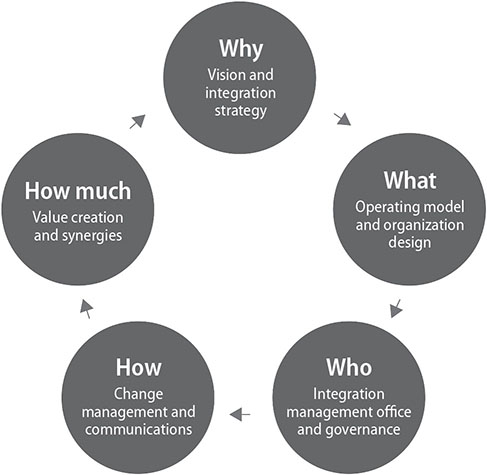

Boards are requesting more detailed integration strategies and road maps as part of their approval process. They want to know the source of synergies, a rough time line to capture value, who will drive integration, how leaders will set up the process so that it does not distract employees or detract from the business, and how it will be funded. This section will help executives to build a robust integration strategy and create that more detailed road map by focusing on five elements of a strong integration. (See Figure 5.2.)

Figure 5.2 Elements of a strong integration

Why: Vision and integration strategy

Deal makers (namely the corporate development or M&A team) need clarity in deal strategy and the expected level of integration, especially with transactions that involve capabilities outside of the buyer’s core competency. If deal makers stray from their original deal thesis and rationale, they may make undesirable or suboptimal compromises during integration. It’s also critical to drive toward more seamless handoffs among the corporate development team, the integration teams, and business leaders responsible for executing the integration.

Recommended actions

- Align the executive team on the deal thesis and value proposition by articulating them in writing. Then create a set of guiding principles that are agreed to by the board and senior management. It should contain elements that help with the many decisions to come. For example, it might spell out which brand will be kept in physical stores versus online. Such a document will eliminate a lot of noise and confusion as the integration moves ahead.

- Keep the guiding principles document current. No integration plan survives intact by the end of Day 1 of the integration, so it’s important to follow the principles when the unexpected happens; however, when major factors surface, you must modify the principles as necessary. The worst situation is to have no document, or a document that has become irrelevant and is ignored.

- Align executives at the target firm on the deal thesis and value proposition, and get the target on board with the integration strategy and plans.

- Do not waste precious time between signing and the close. This period may be as short as 60 days, in the case of a simple public-to-public or public-private deal requiring little or no complex regulatory and shareholder review, or up to two years in the most complex global deals. Regardless of the length of the sign-to-close window, planning and preparing for execution starting on Day 1 are essential. The use of clean teams and other mechanisms available to avoid “gun-jumping” penalties enables a robust preclosing integration process.

What: operating model and organization design

An early and important action is to identify talent pools critical to delivering customer care. If this is not done, you can expect a host of problems that result in lost value, including increased customer dissatisfaction and attrition, and employee disengagement and retention challenges.

In addition, the lack of shared understanding of the target’s cultural heritage can lead to real culture clashes during integration, with the possibility of some of these clashes being quite public. Elements of an organization’s heritage are its organizational values, management style, communication style, approach to innovation, tolerance for risk taking, and other cultural markers. Lack of insight into programs, training, and benefits that support this culture may result in ineffective incentives or real pushback during integration.

We’ve found that the biggest drivers of integration complexity are the number of employees involved, the number of countries where operations are located, the disparity among the two companies’ major information systems, and to what extent the acquired company is a carved-out business requiring transition services agreements (TSAs) and a lot of heavy lifting on Day 1. With integrations that involve thousands of employees and multiple countries, it’s crucial that the integration be directed or advised by people experienced in this type of complexity. After one such integration, we took a moment to count the sum total of actions that were taken. The number was close to 10,000. Given the relatively short integration windows that most organizations work under, experienced guidance is a key determinant of success.

Recommended actions

- Form and maintain a clear view of what the new combined entity should look like, and be involved in all early key decisions.

- Conduct a coordinated organization-design and talent- selection process that leads to robust onboarding and retention planning.

- Design the operating model with policies and procedures that foster the desired combined culture and address culture flashpoints.

- Do not merely integrate if you can transform. Integrations can serve as a trigger event to begin a more fundamental transformation of a company. There is an important difference between integrating (putting two things together) and transforming (rewiring or replatforming and reshaping). A transformation must be a deliberate decision. It means that the acquiring company needs to look as much at itself as it does at the target. This is not easy, but it’s a rare opportunity to be able to effect significant change.

Who: integration management office and governance

Leaders from both the buyer and the target firms must show their continuous commitment to the integration process. They can do this by being visible and active at steering committee meetings, helping to make critical decisions, communicating frequently, and participating in frequently asked questions sessions.

It is not an overstatement to say that integrations succeed or fail because of the chemistry among people and their actions (or inactions). Finance, taxation, operations, and many other factors are highly important, but the people dimension is crucial.

Culture does not change easily, and it does not change with mere words, however true or sincere you make those words. Actions are what count, and words without actions are worse than no words at all.

Recommended actions

- Select key integration leaders early, and don’t be afraid to make changes if needed. Get them involved during due diligence and keep them involved moving forward.

- Engage with leaders of the target to define processes and refine what has worked in the past for their organization.

- Identify individuals to fill roles within the integration governance structure; group members into teams; clearly define those roles, responsibilities, and decision rights; and clearly articulate which decisions each level of the governance structure should make.

- You have a very small window to make tone-setting changes; they must happen right at the outset of the integration. Examples of actions that make people sit up and take notice are a key promotion of someone in the target company, or a “ceremonial hanging” or dismissal of a counterproductive faction leader.

How: change management and communications

At any point, people can lose sight of objectives and slip out of alignment, jeopardizing business continuity, value preservation, and the employee experience. Leaders from both the buy side and the sell side must align their messages, coordinate their delivery, and sustain a consistent, well-coordinated internal and external messaging campaign for the duration of the integration. Such a thoughtful campaign minimizes confusion, frustration, and flight risks among employees, and preserves the value of both the brand and the deal. The more complex a transaction, the more extensive and frequent must be the communications.

It’s helpful to remember that in most acquisitions, a relative handful of people are on the integration team. They know all about the deal, what it involves, and what it does not involve. At the same time, the vast majority of people in both organizations typically hear and transmit constant rumors.

Recommended actions

- Don’t underestimate the importance of regular, clear, and motivating communications in cultural change. Here’s a handy way to think about communication: at the point when you think you have overcommunicated and are simply repeating messages, that’s usually when you are just getting to the right level of sharing information. If employees are standing around the watercooler trying to speculate about a question you have not addressed, that means they are not spending that time building the business.

- Align messages to critical themes aimed at each stakeholder group. For example, employees will want to understand how the merger might affect their jobs and their benefits packages. If that information is not yet available, then say so.

- Remember to include all supplier relationships in critical communications. This includes not just part-timers and independent contractors, but also temporary staffing agencies and technical service providers.

- Develop an employee notification process to stage and coordinate the delivery of these messages, including who should deliver which messages—managers, investor relations, or human resources (HR) professionals.

How much: value creation and synergies

Revenue synergies may be more central to the value proposition for a transaction than cost synergies; however, they may require significant investment and a longer lead time to realize. Lack of comprehensive due diligence efforts may result in unexpected costs. An example is insufficient due diligence on IT assets, specifically the condition and age of the assets, complexity of design, transferability of licenses and security, and stability of the infrastructure. In general, companies often underestimate, or don’t bother to take the time to model the cost of achieving synergies. EY uses a standard of 0.5–1.5 times the recurring annual cost synergies to estimate one-time integration costs.

Recommended actions

- Demand analytical rigor and insight into value creation and synergies, as well as clarity on capturing them.

- Define cost-reduction and cost-avoidance opportunities to help achieve synergies in the short term.

- Conduct thorough due diligence, particularly a comprehensive audit of IT systems on the dimensions of age, condition, complexity of design, transferability of licenses, and the security, stability, and adaptability of the infrastructure.

- When you analyze the crucial staffing question, be sure to ask about “contingent staff” (i.e., contractors) and also people on leaves of absence. There have been documented cases where an acquisition involved several thousand people in this classification, yet they had not originally been included in the head count.

- Thoroughly vet the baseline assumptions and measurement metrics used in the quantification of synergy amounts, and understand sensitivities and interdependencies associated with IT or other capital expenditures.

- Engage integration team members from both buyer and target to align everyone on synergy metrics and time line, and assign responsibility for integrating people, processes, and technology.

- Translate the value proposition into financial and operational metrics to include in the integration plan at a functional level. Clearly define the baseline and targets for improvement within a reasonable time frame within the integration team.

- Establish a rigorous synergy program with clear individual accountabilities to accelerate and exceed targets, and consider striking a balance between both revenue and cost synergies. Make sure accountability is at a high level (e.g. a direct report to the CFO).

- Study the assumptions and expectations behind synergy targets to get a feel for their achievability under a range of scenarios.

- Take the top-down synergy number and validate those synergies from the bottom up with owners early. Assign individual accountability not only for each synergy target, but also for interim targets. This helps to ensure that you stay on pace to realize the overall synergy goal.

- Develop a robust plan for the one-time investments required to achieve the targets, especially for revenue and growth, and include a realistic schedule of capital expenditures.