6

Are you planning and executing divestments for maximum value?

On the heels of a major acquisition, a global medical technology services company began considering a potential carve-out. The options were either to invest more in the business in order to meet regulatory requirements, or to sell to someone else. Management decided to divest because the business had limited long-term growth potential and was inconsistent with the company’s core operations and strategy.

All aspects of the unit were carefully considered, particularly customer overlap with other parts of the portfolio, as well as its significant revenue and earnings contributions. To determine exactly which package of assets would be most attractive to potential buyers, the seller examined four different deal perimeters, carefully crafting a value story for each. Adding to the carve-out’s complexity: the business’s activities in finance, tax, information technology, and operations were interdependent with the parent across 50 countries.

Significant up-front separation planning across key functions began 8 months before signing and 11 months before close. This thorough preparation allowed the seller to continue to focus on running the business and maintaining its value along the way. The unit not only attracted both corporate and private equity buyers, but also garnered a price 12% above initial expectations. Though many complex carve-out transactions take well over one year, this transaction occurred within a tight 11-month time line, was highly successful, and provided much needed capital for debt repayment and future acquisitions.

Divesting is critical to your capital strategy

Divestments should be a fundamental part of your Capital Agenda, especially in a volatile and disruptive environment where you need to fund growth and essential innovation. In our experience, most companies act too slowly and hold on to assets too long. Monetizing noncore and underperforming businesses helps companies redeploy resources to invest in digital capabilities, expand product ranges, and broaden geographic footprints.

Divestments can be an efficient route to unlocking hidden shareholder value, because they generate cash and often lead to an improved share price for the remaining company—if done well. External forces, including geopolitical uncertainty, macroeconomic volatility, technology-driven risks and opportunities, regulatory changes, and shareholder activism, can also spark divestment discussions. Such external forces will continue to drive divestments for the foreseeable future.

What defines a successful divestment?

Before delving into the mechanics of divesting, let’s define what we consider success. On one level the goal is to achieve your strategic imperatives; but to get more specific, we use these core criteria:

Maximize sale price

Based on our research and observations, almost half of divestments fail to realize sufficient value for their shareholders because companies tend to underprepare, and then focus too much on speed to close. It’s a costly mistake to get into the mindset of “We need to just get rid of it!”

Close the deal quickly

Our research shows companies are 60% more likely to beat their sale price expectations when they prioritize value over speed.1 Although managing the trade-off between speed and value can be critical, it is usually a false trade-off. Many companies rush to get the deal done, but in the process cut corners during preparation. As a result, the deal takes longer to close and its value declines, because potential buyers have less faith in the value story. Sellers are much more likely to maximize their sale price and shorten deal duration when they take time up front to prepare the business for sale.

Achieve an enhanced valuation multiple for the remaining company

Just as the buyer wants reinforcement that the purchase was a good decision, the seller’s confirmation of a good decision is manifested in a strong valuation multiple for the remaining company.

Divestment guiding principles

Successful sellers understand that carving out a business is typically far more complex than acquiring one. Executing a divestment requires planning, effort, and urgency. “Thinking like a buyer” helps you control and expedite the process, as well as maximize value. These guiding principles should be applied before marketing commences:

- Define the perimeter of the transaction early. Which components are included and excluded? Should the business be sold as a whole, or split and offered to multiple buyers? Though the perimeter often changes, this is a cornerstone of the planning process because it can affect all other carve-out work. The key is to remain flexible and agile as the deal evolves.

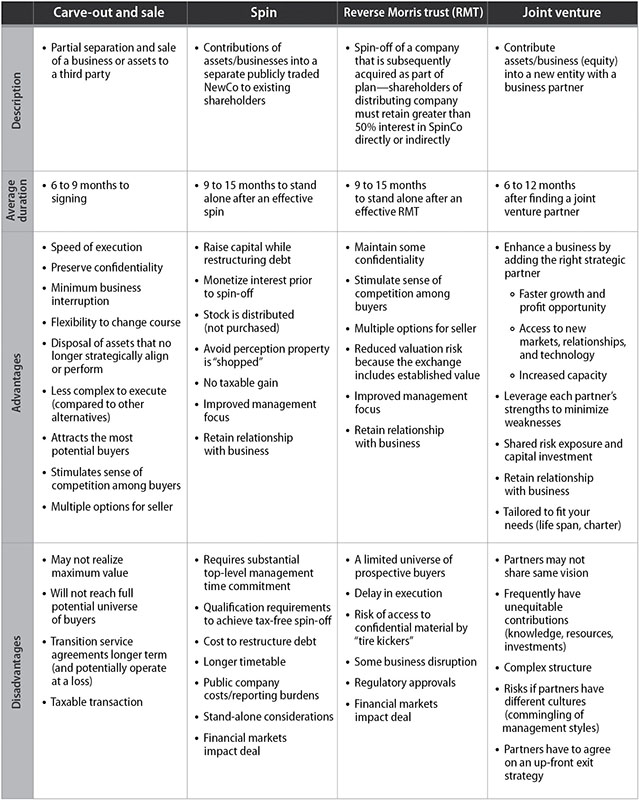

Fully consider transaction alternatives. Companies should explore alternative structures to achieve the optimal transaction outcome. Though every divestment will have unique features, most transaction types fall into four main categories, as shown in Figure 6.1.

Further, companies often dual-track transaction structures to maximize value for their stakeholders—pursuing both a spin-off to public investors and a third-party sale—until a clearly superior option emerges.

Develop a buyer mindset. By doing so, sellers can better understand value drivers and consequently tailor information to maximize value while shortening the divestment process. Figure 6.2 describes focus areas for both strategic and private equity buyers.

Sellers must identify and understand their pool of potential buyers to evaluate their purchase and valuation perspectives. Then they must provide a comprehensive plan for how the unit will be operationally separated from the parent and fit into the buyer’s portfolio. For example, PE buyers usually are interested in a stand-alone basis whereas strategic buyers care about the synergistic view.

Plan for separation early. Successful sellers understand that unanticipated separation issues can lower the value to potential buyers who desire a functional business. The appropriate governance structure—with representation from the board of directors, corporate development, finance, tax, operations, human resources, legal, and investor relations—supports the creation of an appropriate project plan with key milestones throughout the divestment life cycle. Rigorous planning and adherence to processes will help sellers avoid value-destroying surprises.

To illustrate: on a quarterly investor call, a CFO committed to a closing date for a significant spin-off without checking on feasibility with the deal execution team.

During the separation process, the company discovered regulatory hurdles in numerous countries that delayed the transaction by six months. The company’s stock lost more than 20% of its value post announcement and did not recoup its losses until well after separation.

- Address all stakeholders. Do not leave employees in the dark to imagine what may happen and thereby risk losing key talent. Involve individuals with mission-critical knowledge and capabilities early on to help you make the most informed decisions. Though this may seem obvious, the reality is that often the very people who really know the business to be divested are not included early enough, often because of concerns over confidentiality. Clearly communicate the strategic rationale behind the divestment and its intended effect on shareholder value. Don’t forget about external stakeholders, whether they be shareholders, creditors, customers, or vendors. Frequent communications instill confidence.

Figure 6.1 Transaction structuring considerations

Figure 6.2 Buyer focus areas and criteria

Leading sources of value erosion

- Operating performance deteriorates, undermining your value story.

- Incomplete due diligence materials reduce buyers’ willingness to bid competitively.

- Lack of flexibility in transaction structuring fails to attract optimal buyer group.

- Inadequate resources are devoted to executing the transaction.

- Insufficiently developed and documented stand-alone costs scare off financial buyers.

- Tax due diligence and planning fail to anticipate needs of each buyer group.

- Missed opportunities to fix or improve the business before the sale suppress value.

- Senior management commits publicly to an unachievable closing date.

Can you increase business value before divesting?

We often hear executives say, “It doesn’t make sense to invest in a business we are going to sell.” On the contrary: when a company begins to explore strategic alternatives, the highest priorities for any seller should be to strengthen the business, develop the equity story, and execute on a seamless separation. This requires you to regularly evaluate trade-offs between initiatives to improve the business and their associated costs.

Value enhancements come in two flavors: those you can implement before beginning the divestment process, and those you don’t make but can credibly describe to potential buyers. For this second category, sellers should demonstrate a road map so a buyer can execute on the improvement plan. Some ways to create value include:

- Treat the business as a stand-alone entity. Sellers encourage buyer confidence when they can provide separate financial and operating results for a to-be-divested business. When a business has been earmarked for sale, sellers should explore the feasibility of internally reorganizing to put the business on a stand-alone basis. Key focus areas include:

- Go-to-market models, such as direct versus distributors.

- Financial reporting, including balance sheets, income statements, working capital, and forecasts.

- Rational cost allocations or, better yet, direct costs.

- Appropriately capitalized legal entities.

- Legal and regulatory requirements in applicable countries, particularly those that may prohibit a buyer from operating the business on the desired closing date.

- Enhance revenue. Although an extensive product expansion program may be unrealistic for a business for sale, companies can start to optimize their product footprint across customers and geographies. A bolder move is to add products or expand into different geographies or markets through a joint venture arrangement, or to consider acquiring another company. A global private equity fund completed several bolt-on acquisitions to bolster its real estate portfolio: it acquired commercial estate to expand in geographies and also a carved-out business of a large corporation to add size and scale to the asset.

- Extract working capital. Buyers generally won’t pay for excess working capital. Companies planning to divest a business need only enough working capital to run the business on a day-to-day basis. Any amount beyond that should be liberated prior to beginning the divestment process and put to work elsewhere, as we discuss extensively in Chapter 8.

- Cut costs through procurement. Companies can enter into group-purchasing agreements, or even form their own buyer consortium to reduce costs and enhance margins.

What does it take to close the deal and maximize value?

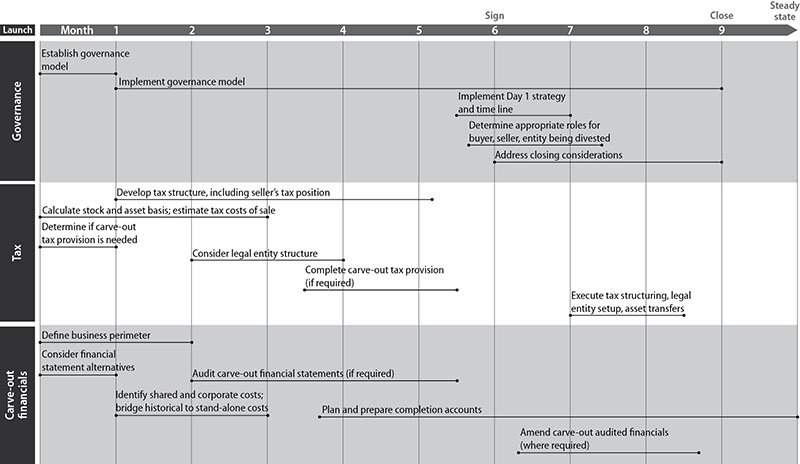

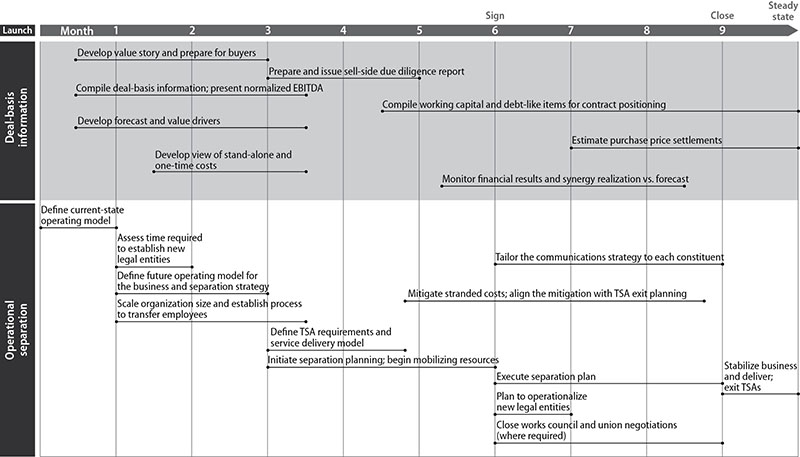

Most companies do not divest as often as they acquire and don’t recognize that divestments are complex and require thoughtful governance, resourcing, and prioritization across all functions. The activities of the tax, financial, and operational separation work streams must be prioritized against competing initiatives within the organization. Figure 6.3 contains a brief overview of a typical divestment work plan. While this chapter covers divestments of all types, here we’ll focus in detail on carve-out transactions as an important example.

Figure 6.3 Divestment work plan

Let’s look at each of the essential focus areas.

Governance. Executing a successful deal without undermining core business operations

Leadership needs to establish a governance structure that defines the transaction time line, milestones, roles, and responsibilities. The separation management office (SMO) should have representation from the entire enterprise, including tax, finance, supply chain, IT, human resources, legal, and communications. With the SMO in place, each team must be appropriately resourced with those best positioned to execute, not simply those who are available. This often entails a combination of internal and external resources.

Tax. Structuring the deal to minimize tax risks

We often hear, “There is little benefit to tax planning when we don’t know who the buyer is.” This can be a costly mistake: tax issues can make or break a deal because of their economic effects on both seller and buyer. Our research indicates the majority of sellers neglect to effectively communicate tax upsides to bidders, thereby failing to maximize value. The most successful sellers consider tax early in the process, and proactively consider the tax needs of possible types of bidders—corporate versus private equity, domestic versus foreign. Enhancing a transaction’s tax structure requires detailed knowledge of historical tax risks and upsides, as well as an understanding of how to mitigate tax costs while maximizing upsides to benefit both the buyer and the seller. See Chapter 9. Some essential practices:

- Ensure tax, finance, and corporate development are aligned with the deal-basis financial statements to ensure that the right information drives critical decisions.

- Determine which legal entities will be sold as stock versus assets, and calculate tax gain or loss. The anticipated tax bill may drive a “go/no-go” decision and help to focus on how to maximize after-tax proceeds.

- Consider a legal entity structure that helps drive value for a buyer by optimizing taxes on sale and repatriation of proceeds, as well as future operating earnings.

- Anticipate required tax provisions. Will full generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP)–compliant financial statements be needed, or will bidders accept special-purpose or abbreviated statements?

Some examples of common tax-efficient divestment strategies:

- Tax-free spin-off. An existing business is separated out of a company. Shares in the spin-off entity are distributed directly to the company’s existing shareholders. When appropriately planned and structured, sellers can divest appreciated assets without incurring US federal income tax.

- Reverse Morris Trust (RMT). A number of companies, particularly in technology, in recent years have completed RMT transactions, allowing for a tax-free spin-off of the business followed by a third-party acquisition of a minority interest in the spun-off entity. These structures apply only in specific fact patterns, but in the right scenario they allow sellers to monetize a significant portion of their ownership interest without incurring tax.

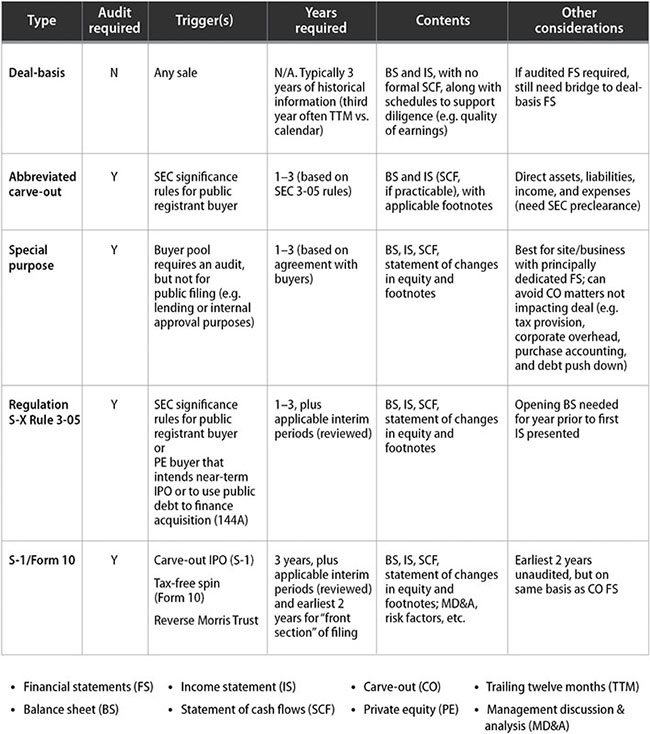

Carve-out financials. Preparing for the buyer pool and their financial requirements

Carve-out financial statements, whether on a deal basis, audited, or both, are paramount to the success of any divestment. We often hear, “Existing information will satisfy any deal-basis financial statements,” or “Why prepare audited financial statements? Most buyers don’t require them,” or “They can get a waiver.” Here are some counterarguments:

- Does your internal financial information reflect the anticipated perimeter of the transaction and related operations? If not, how will prospective buyers understand the assets, liabilities, and working capital to be transferred? How will they understand the cost structure they will assume? How will the tax team determine the appropriate structure and gain/loss on the sale?

- Does your buyer pool include private equity buyers? If so, audited financial statements are typically required.

- Will your buyers, whether corporate or PE, require debt or equity financing? If so, audited financial statements are also likely required.

Although preparing financial statements for a divestment is time-consuming—three or more months for deal-basis financials and nine months or more for audited financials—deficient statements can easily derail your deal.

Figure 6.4 illustrates types of transaction-related financial statements and their triggers.

Figure 6.4 Financial statement requirements

Despite the extra effort required, audited financials can support a bigger buyer pool, increase competitive tension, and enhance valuation. Identifying the potential buyer pool needs to happen as early as possible.

Deal-basis information. The key elements of a strong value story

Deal-basis financial information should represent a summary of those assets, liabilities, working capital, and operations anticipated to transfer to buyers. They will be subject to extensive due diligence and form the basis for bidders’ valuation analysis.

- Define the perimeter of the business and how it might be packaged; identify the optional components that may later be included or excluded.

- Use the governance structure to align the deal teams with the perimeter so there are no surprises later in the process.

- Perform defensive due diligence on the financial statement components. Are amounts direct? Do they contain allocations? Will they withstand buyer scrutiny?

- Bridge the deal-basis and audited financial statements. There generally are significant differences, and being able to articulate those to potential buyers will enhance your credibility as a seller and help facilitate the sale.

Provide a Compelling Value Story

Buyers want a due diligence package that delivers a strong value story and links historical results with operational forecasts. They’ll expect a comprehensive, self-service virtual data room that supports buyer confidence in the numbers. The following are some critical steps to take:

- Develop the divestment rationale, anticipate buyers’ value drivers, and tailor materials to support their needs.

- Compile deal-basis information that includes normalized EBITDA so buyers can index purchase price to an EBITDA multiple.

- Create a view of stand-alone and one-time costs that can withstand buyer scrutiny. This helps influence buyers’ assumptions about operating model, potential synergies, and projections.

- Prepare a sell-side due diligence report. A well-prepared and comprehensive seller due diligence report will help enhance competition and expedite buyers’ analyses.

A supportable investment thesis and deal-basis financials help maintain your credibility and control in the negotiation process. A counterexample: a global manufacturer was negotiating to sell its noncore business to a private equity firm. Although the seller prepared deal-basis financial information, it did not provide an estimate of stand-alone costs. During the negotiation, the buyer put forth its own calculations of normalized EBITDA with stand-alone and one-time costs. Its sustainable profitability assumptions were significantly lower than the seller’s would have been, resulting in a considerable reduction to the offer price. Negotiations dragged on, and ultimately both parties walked away from the transaction.

Operational separation. Planning for a speedy close

We often hear, “It doesn’t make sense to begin planning for the separation of the business until we have a buyer.” On the contrary, rigorous up-front planning must start well before identifying a buyer, to ensure a timely closing and deliver a functioning business on Day 1. Starting early provides a much clearer view of the key decision points and enables you to minimize disruption, reduce complexity and cost, shorten the time between sign and close, and reduce the scope of transition services agreements (TSAs) and transition manufacturing agreements (TMAs).

Leading-edge separation planning begins with analyzing commingled services to enable early development of TSAs/TMAs and stranded costs modeling. Identifying long lead-time separation activities helps avoid delays in the deal time line. For example, IT is often the most entangled functional area and the one that requires the most lead time, and it is typically the most expensive to separate. As part of setting up your SMO, establish a dynamic talent management process that provides the right resources for each work stream, but also supports the day-to-day needs of the business.

Design the operating model

A credible separation strategy shows buyers the business can be separated without loss of value. This includes defining both current and future operating models. Although the buyer will eventually stand up all the functions, you’ll likely need to provide transitional support in order to hand over a fully operational business. Understanding the buyer’s future-state operating model allows you to identify long lead-time items—such as establishing new legal entities—and provide the service delivery model for Day 1.

In addition to separation complexity, the time line will be driven by the buyer’s capabilities and desired closing date. Buyer and seller should understand and fully discuss lead times to address closing conditions such as antitrust, works council, and other regulatory approvals. This allows both parties to develop work-around solutions to meet the closing conditions on schedule. For example, market authorization requirements often require an interim operating model for Day 1 with the buyer.

Define TSA requirements

Seller and buyer also need to align on guiding principles, including an approach to separating each function. Agreeing early about the delivery model for transition services will help both understand their costs to operate on Day 1. They will also be better able to plan for exiting TSAs. A proactive approach allows the seller to identify and plan for remediating stranded costs.

Finalize work-arounds for long lead-time separation activities

Understanding long lead-time items early is crucial because the post-signing period rarely includes sufficient time to begin and complete key activities. For example, requirements to establish new legal entities vary widely and can take more than a year to fulfill. Failure to move quickly can delay establishing bank accounts, contracting with vendors, configuring systems, and selling products, all of which can postpone closing. It is critical to determine IT requirements to put new legal entities into operation, segregate data and access, address name changes, and enable separate financial reporting.

An example of effective planning: a global equipment manufacturer determined that one of its business units was not core to its future strategy. Even though a final decision had not been made to divest, management began addressing long lead-time separation activities to facilitate an exit and minimize the need for TSAs, which would distract from running its core business. Key steps included establishing new legal entities in countries where existing operations were commingled with the parent, cloning the current enterprise resource planning (ERP) system hosted by a third party, and arranging contracts with external service providers for payroll and similar services.

When a decision was made a year later to sell the business unit, the private equity buyer had confidence in the ability of the business unit to stand alone, resulting in a simplified operational due diligence process and a quick closing. The seller concluded that the up-front costs to implement these changes were more than justified by the sale proceeds, early close, and minimal TSAs requested by the buyer.

Divesting for value

In an age of market disruptions and impatient shareholders, strong divesting capabilities should be part of every company’s Capital Agenda tool kit. The first bulwark against value erosion is rigorous portfolio reviews. Perhaps the most value-damaging action a company can take is holding on to an asset too long.

Once you decide to divest, thinking like a buyer is critical to success. Sale preparation is vital, even for the best-performing unit. Flexibility around the deal perimeter and structure can be the ultimate path to success. Start operational planning early in the process to accelerate speed to close while creating value for both seller and buyer.

Even after a successful divestment, significant opportunities exist for enhancing the value of the remaining business. Once TSAs expire, certain costs aren’t passed through and remain stranded with the seller. Stranded-costs management is one of the greatest challenges for the remaining business. Proper separation planning and execution will allow sellers to identify and remediate the stranded costs.