11

How can you get the most out of your advisors?

Giri Varadarajan and Aayush Tulsyan

Successful automotive equipment companies must focus on three goals: winning new customers, retaining existing customers, and maintaining customer satisfaction through the life cycle of equipment ownership.

A global industry player was struggling to achieve these goals in Japan, and called in our colleagues from the United States to analyze its 160+ dealers in Japan and to work with them to develop an effective solution. The expected thing to do in this situation would be to hire a local advisor that understands the language, culture, and business.

Why hire advisors from the United States to help fix a problem in Japan? The client concluded that it had the required local business and cultural knowledge; however, it lacked sufficient process expertise and the ability to design and implement a standardized solution across the country—so it sourced the optimum talent globally. The client arrived at this decision after thoroughly evaluating its strengths and weaknesses, and clearly defining what it wanted from an advisor (more about this later in the chapter). EY worked with the client to develop a balanced scorecard at the outset of the project to define what success would look like for the dealer business. This helped keep everyone focused on the same goals, even with cultural and language differences.

The effort began by building trust rather than launching a national project. We developed a hypothesis, conducted interviews, and framed initial recommendations based on these learnings and our past experiences. This process gave the client an opportunity to assess us as an advisor and possibly even as a journey partner1—a distinction we’ll cover later.

As the project progressed from design to implementation support, we shifted our team mix to a larger proportion of local members, who would be more adept at change management and working with local and regional dealers to roll out these changes. This helped the client achieve a successful implementation of the project across Japan.

Setting the context

Let’s address the elephant in the room: we’re advisors, and this is a chapter about how to work with advisors. You might expect we would be unqualified advocates for hiring advisors, but our recommendations are more nuanced.

It would be bad and less credible advice if we said, “You definitely need advisors.” The proper answer is that it depends on the problem you need to solve or the opportunity you want to capture.

We will explore good and bad reasons, as well as mistakes, such as hiring advisors prematurely and keeping them too long. This chapter will give you advice about getting advice, and put it in the context of optimizing your Capital Agenda.

First principles

It’s important not to confuse “getting advice” with “getting advisors.” We all get advice daily—whether solicited or not. The problem is that sometimes you need to go beyond casual suggestions and make substantial progress toward a defined goal. That’s when you might consider getting an advisor.

A Fortune 100 senior executive whom we greatly respect, and who has worked with many consultants, has this to say about why to hire an advisor:

At the end of the day, the only reason to hire an advisor is to change the outcome of a situation, whether it’s an opportunity or a crisis. You do that by getting an advisor whose proven methodology is directly applicable to the problem you’d like to solve.

Other executives who’ve successfully used advisors do so:

- To get an unbiased, outside-in assessment of a situation.

- To confirm—or question—the feasibility of a proposed solution.

- To receive insights and perspectives based on expertise and experience.

- To help apply leading practices in order to solve a problem.

- To help an organization raise its capabilities to a higher level.

You should not expect to get a so-called answer or silver bullet from a good advisor. If that’s what you’re looking for, you may be making a mistake. What you get from an advisor are insights, coupled with strategic thinking, that challenge the status quo. What’s more important is that you get a set of capabilities to help navigate your organization through a complex situation. With the help of the advisor, you co-create the thing you’re trying to get done, and that goes well beyond an “answer.”

A highly underappreciated element of working with an advisor is the methodology that an advisor brings to the project. You should not be buying merely advice. The right methodology can help to unlock the creativity and insight of your internal team. It also helps to structure and organize the work, which helps turn insight into actionable strategy. That then supports the outcomes you’re looking for. More on this later.

When it is appropriate—and not appropriate—to use an advisor

When do you know that it’s time to bring in an advisor?

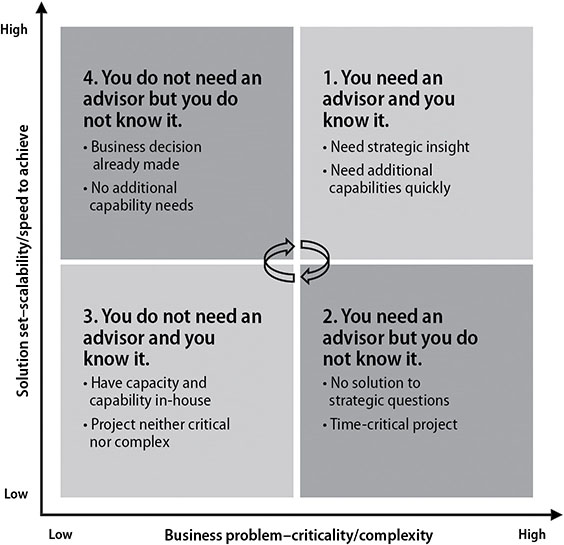

You can do just about anything yourself without advisors. But getting an advisory firm on board can help in certain specific ways. Then again, some situations may seem like the time to bring in an advisor, but are not. Let’s look at various scenarios (refer to Figure 11.1).

Figure 11.1 When is it appropriate—and not appropriate—to use an advisor?

Every situation falls into one of four quadrants:

1. You need an advisor and you know it

To get strategic insight. You are at the crossroads of choosing a strategic option or making another important decision. You conclude that it would be helpful to have someone guide—and occasionally force—you to thoroughly think through the alternatives, using a proven approach. An advisor can clarify and help establish benchmark criteria for success, and assess your ability to acquire and maintain those capabilities.

To accelerate a process. You’re in a relatively new market and have captured modest market share, but now that market is heating up, with new, cash-rich competitors. How can you reconfigure your supply chain and commercial model to gain much greater market share in the next 12 months?

You need additional capabilities quickly. You have a line of successful consumer packaged goods in Europe, and want to explore expanding that line into Latin America. You learned the European market on your own and could do the same with Latin America—given enough time—but the window of opportunity doesn’t allow that luxury.

2. You need an advisor but you do not know it

You’ve wrestled for a long time with certain strategic questions without coming to a resolution. They may involve concerns around restructuring, disruptions in your industry, a steady erosion of margin, or other value-depleting trends.

You have no data about how long certain initiatives should take and what they should involve (such as entering a new market), and you’re not sure how to go about finding the right solution.

You’re in a downward spiral of cost cutting and are unable to invest in technologies, people, or advisors who might get you out of the slump. This situation leads to more cost cutting.

You’re struggling with breaking down the situation and defining the specific questions to be answered.

You need a specific set of analytics capabilities and tool set during the due diligence period, and you don’t have this internally.

3. You do not need an advisor and you know it

- A project has ended.

- You’ve built robust capacity and capability in-house.

- You’re able to staff up and down without creating problems.

- The project is neither critical nor complex.

- You have sufficient time to execute your plans.

4. You do not need an advisor but you do not know it

An executive might say: “I’ve decided to buy Acme Industries. I’m making my offer next week and I need a second opinion because I think I may get a lot of pushback from my board.” If the decision has already been made, then the advisor’s ability to add value will be limited. However, if the advisor is given the freedom and information to provide an independent and objective perspective, then such a second opinion may be useful.

You should be hiring advisors because they do things differently from the way you do them. They should not be brought in to rubber-stamp decisions already made, or to manage corporate politics. Confirmatory advice can be helpful (or even necessary) from a governance perspective, but you should be wary of paying someone to tell you things you already know. Advisors would have been more valuable if they had been brought in upstream from the decision to buy Acme, at the stage when they could help explore options. Early on is the time to ask focusing questions:

- Given your strategic objectives, where is your next big opportunity?

- Are there organic growth options to achieve your goals?

- What are the industry trends you’re seeing, and which opportunities are you uniquely positioned to harvest?

- What company could you potentially buy, or partner with? How does Acme fit into that picture?

It’s also okay to hire an advisor if Acme is in play and you want to think through quickly whether it makes sense to do a deal there, but not because you’ve already decided and want a second opinion. Maybe you’re already down the road in the decision to purchase Acme, and want someone to help you with contractual protections, valuation, negotiations, integration, tax structuring, and so on. That could be an appropriate time to hire an advisor for expertise in those areas.

Let’s say you’re understaffed in a country and you think that maybe the advisor can be your arms and legs on that project. Advisors should be hired to apply their proven processes to your business objectives, and not as additional full‐time equivalent (FTEs) on your staff, unless it’s for a true short-term engagement to keep time lines moving.

Staff augmentation is a perfectly legitimate activity. A large advisory firm might even have units that perform that role, and they may do it well. What’s important is to recognize when you’re hiring an advisor for the ability to support decision making, and when you’re hiring someone in order to augment staff.

Hiring process

It’s not uncommon for companies to select an advisory firm through a process that somewhat resembles the TV talent show model. Companies send out a request for proposal (RFP) to multiple firms, ask for written responses, and then schedule presentations by those firms. Sometimes several advisors will be given 90-minute windows to present, and are stacked back-to-back during one long day. At the end of that marathon, the client chooses an advisor.

That serves the best interests of neither the client nor the advisors. Most such talent shows provide only a superficial understanding of client objectives and the advisors’ capabilities.

Some small amount of this process may be unavoidable, in the sense that multiple firms are reviewed in a short period. However, if you’re moving into an unfamiliar space, the best way to decide on an advisor is to meet people from the relevant firms in a less-than-formal setting. Explain your business objectives, and then tell the advisors a little bit about what you’re doing and why.

Then have them provide some initial thoughts and insights. As the client, you should be listening for three things:

- Would I enjoy working with this person?

- Can I see myself being vulnerable in front of this person? That may sound like an odd question, but in reality if you’re going to benefit from advice, you need to be humble enough to receive it. Is this person somebody that I could have a good enough rapport with that I could handle getting frank advice from him or her? Can I be comfortable enough with this person to have productive back-and-forth interaction to effectively handle necessary course corrections?

- Would the advice be worth taking? In other words, what is the quality of the advice, based not only on the person’s experience, but also on the experience and capabilities of the team around him or her? Does this person have the substance to help me move into some area that’s new to me?

What I’d next like to hear from the advisor during our conversations is something along the lines of “Okay, I answered the questions that your procurement process required. I addressed the scope of the project as it has been outlined. What I’d like to do now is have a chance to recommend some things that I would either limit or suggest you modify in the scoping document, in order for this to turn into a successful business outcome.” These additional elements might be insights or perspectives gained from the advisor’s experience, and this sort of response indicates independent thinking and ownership of the project. Can the advisor also start to anticipate some of the critical implications that may be outside this engagement but will be a result of the course of action?

This would also tell me I’m not just being told what someone thinks I want to hear. The advisor may indeed have a vision, strategic thinking, and methodology that’s different from my preconceived notions, and that may produce better results for us. Remember, you’re hiring advisors because they bring expertise and perspectives you don’t have in-house.

Don’t choose advisors based on the lowest cost, but instead on the best value in terms of the right fit, capability, and experience they bring to the engagement. In the long run, this approach will help you to avoid cost overruns, dead ends, and lost value. Getting the right advice, in a timely manner, will almost always be more cost effective than having an unsuccessful or inefficient project drag on at a low hourly rate.

Speaking of the engagement, you need to have as clear a statement as possible about its scope and nature, including what success looks like in terms of your key desired outcomes. Advisors run the gamut from strategy firms to ones that encompass major areas like operations and finance, and to ones with highly specialized expertise in crisis management, cybersecurity, and so on. The proper match between you and an advisor can be made only when your problem statement and desired outcome are as clear as you can make them.

How to do proper due diligence on advisors

Your personal network is larger than you think it is. That’s true for everyone. Social media business tools are surprisingly powerful not only for contacting your connections, but also for doing quick research about who knows whom. Often just one or two well-placed emails can get you in touch with people who have a wealth of information on the advisors you’re considering.

Ask the advisor to give you an overview of how he or she would approach your challenges, including a description of their methodology. That might also include a 90-minute workshop for a handful of people on your team. During the workshop, the advisor should walk you through an example of a similar project that the company did, including what went well and what could have been done better.

The advisor should be able to provide sufficiently anonymized case studies that convey the team’s approach and expertise without disclosing the name or identifiable details of the actual client being discussed. In many cases adequate anonymization can be achieved by changing names, statistics, locations, and organizational structure, while preserving enough of the methodology and insight to demonstrate real-life expertise. Experienced advisors tend to publish white papers, case studies, special reports, articles, and books. Take the opportunity to look at what’s published, and study the tone. Are you reading material that contains generic information or real insights? Does the material simply describe what the advisor did on projects, or does it cover specific business outcomes?

Ask to speak with other clients who have worked with the advisor. Your questions can cover some of the areas we’ve just listed; for example: What is the advisor’s methodology? To what degree did the advisor make you think hard about topics, and maybe even challenge you? What are the advisor’s strengths and not-so-strong areas?

Then ask to speak with some of the team members who will be doing the day-to-day work on the project. It’s important to understand their capabilities and gauge their ability to deliver unbiased advice, rather than merely accept whatever you say.

Advisors as competitors and as peers

This is a good place to bring up the topic of other advisors, first in the context of competition.

As part of your due diligence and interviewing process, ask: “Whom do you see as your competition?” That simple question sometimes can speak volumes.

What you don’t want to hear is “Oh, it’s my policy not to say anything negative about the competition, but instead to stick to the topic of how I can help you.” To which you should respond, “I don’t want you to say anything that’s untruthful about your competitors, but I do want to hear how you differ from them in specific ways.”

Then ask: “What do you do really well that you’re particularly proud of? What are some areas where your competition does things either differently or perhaps even better? If you were working on this project and a couple of areas were outside your sweet spot, how would you suggest we go about getting someone else to help with that, and what’s your recommended path for working with them?”

These last questions will tell you a lot about the advisor. Is this person unwilling to admit that anyone comes even close in ability, or has strengths in other areas? Does the advisor look surprised at the question and then say that the only circumstance where there could be another advisor brought in is if this advisor controls the other as a subcontractor? In our experience, these sorts of defensive responses tend to foreshadow problems down the road.

On the other hand, you may find that the advisor is both experienced and humble. “We’re strong in cross-border taxation, but not as strong in the evolving area of cryptocurrencies. If you need both, then you may want to bring in someone that specializes in crypto work. We can walk you through where we have effectively teamed up with other advisors to bring the best business outcomes to the situation.”

If you as the client have clearly stated the business outcomes you need, then having more than one advisor—with equally clearly stated areas of responsibility—means that the advisors should not trip over each other.

Note: Don’t be the client who says (and we’re not making this up): “I want a single throat to choke across bankers, attorneys, and advisors.” Sometimes complicated business outcomes require the insight and support of multiple organizations. An experienced, high-quality advisor almost certainly will not agree to be that single throat, because the statement may be indicative of a predisposition to assign blame instead of working through difficult issues. Of course, it’s perfectly acceptable—and a leading practice—to insist that an advisor provide a single point of coordination across his or her own work streams. While good advisors will normally resist taking responsibility for another advisor’s work, they can provide project management support to help you keep the process on track.

How to start the relationship with an advisor

Let’s say you’ve navigated the process and have chosen an advisor. What’s the best way to begin to work together for the first time? Is it to dive right into your big project, or to create some type of pilot project to see how things work?

We suggest neither approach. Instead, we recommend that the main project for which you hired the advisor be broken into natural stages. Let’s take an integration, for example. You’ve decided to buy a company and need to do some planning around finance and operations before you make the final offer. That would be one natural stage of the project.

The next stage might be the period from “sign to close,” followed by “close to Day 100” and so on. Then you could say to the advisor, “I would like to know your total capabilities and your general approach to the project. But I’d like to see the work broken into discrete phases. As we transition from one phase to the next, I want to do two things: reflect on how well we’re working together, and also build some capabilities internally.”

Each stage is unique and separate, but part of the overall project. Obviously you have the right to change horses at the next stage, but that’s not the reason you’re working in stages. The objective instead is to be able to have outcomes to evaluate and learn from at each stage.

Fourteen other leading practices (and what not to do) when hiring and managing advisors

- Be very careful about allowing middle managers complete freedom when hiring advisors. You may think: “I want my middle management to take ownership.” If they have never experienced this type of project or transformation, then it’s a recipe for problems. Advisors could also be perceived as a threat because they might make middle management look bad. Sometimes not the best people get hired, and even if they are the best, they may be constrained in ways that do not maximize their value. At the very least, plan to stay involved in this crucial process to ensure that advisors are given enough freedom to provide the right advice, and that their input is carefully considered.

- Do not set arbitrary constraints. Criteria like “We want to use the advisors that are local to a given region” are not productive. The problem is that advisors are not interchangeable commodities; you want the right team for the specific job. Region-specific expertise may be an important consideration, but not the only one.

- Do not consider the advisory staff as a static entity. Few aspects of business are static. In most projects, the advisory team size and composition will evolve as phases change. For example, an acquisition advisory team may have a relatively large number of tax structuring specialists early on. In the later phase of the project there may be fewer of those experts and more people focused on operational integration.

- Be sure to align incentives. You’re asking for problems if your people are incentivized in one direction (lowering unit costs in your plants, for example) but your advisor might come back with recommendations that are counter to those incentives—such as lowering inventory levels to free up cash. The CFO is usually best positioned to balance these forces, and can be an active coach to middle managers, who work and drive the project on a daily basis.

- After you’ve hired an advisor, listen to her or him. Provide the advisor with as much access to people and information as you can. Treat the advisor with the same courtesy as you do your own employees. You co-own with that advisor the performance and business outcomes.

- Watch for scope creep. Continue to be as clear as you can about what you want to accomplish, and be on the lookout for the sorts of conversations that cause scope creep. If you start to think that may be happening, step back and make sure that you understand the time and money implications of the contemplated changes. They can be okay as long as you have regular, robust discussions at both strategic and operational levels. Everyone from executive sponsor to middle managers needs to be part of this dialogue, and the scope should be modified only with great care.

- Continue to learn about the advisor’s methodology, and work on complementing each other’s skills. Don’t tell the advisor how to run his or her process and what set of tools to bring to solve the problem. If it turns out you don’t like the process, it’s time to hire a different advisor.

- Review the knowledge transfer every three to six months, depending on the project phase and level of activity. Make sure you’re letting advisors know that you will ask, “How are you transferring best practices and knowledge to us, so they become part of our routine?” Good advisors want to do that because they are looking to build long-term relationships.

- Regularly evaluate whether you are able to take over this project internally. Have you met your original objectives? By the way, if you have, then be sure to highlight any standout performance on the part of the advisor. Praise is rare and valued, even when it’s completely deserved.

- Know when it’s time to end the project. A good advisor will come to you and say, “You don’t need us for this work anymore.” It’s a matter of protecting the advisor’s brand. That’s better than making you feel later that you were strung along and now don’t want to hire that advisor again. From the advisor’s viewpoint, a strong long-term relationship is more valuable than an incremental one-time fee.

- Be alert to the nature of surprises. Has the advisor surprised you? Examples of a good “yes” are beating deadlines and delivering exceptional quality in terms of thoroughness and ease of use. Examples of a bad “yes” are unexpected fees or expenses, not delivering what was expected, and not proactively communicating when circumstances changed. Assessing the nature of surprises is one good way to know if it’s time to end the engagement—or to consider moving forward and deepening the relationship.

- Codify learnings. It is a good sign if your advisor takes the initiative to create a document with lessons learned, or a playbook to help you with similar projects in the future.

- Periodically review scope, team size, and budget. Does the advisor manage your money as if it’s theirs? Good advisors should sometimes be able to return unused budget dollars if they’ve managed the project well.

- Have open discussions beyond the current engagement. What has the advisor observed and learned about the business and organization? What opportunities or threats does the advisor see that may not be on your radar?

Beyond advisors to journey partners

At the beginning of this chapter, we talked about the difference between advice and advisors. Now we’d like to make some further important distinctions.

You say to a vendor: “I need a knee brace.”

You say to an advisor: “I have a knee issue.”

You say to a journey partner: “I didn’t even know I had a condition; thanks for the early diagnosis.”

In the business world, all three functions are important and necessary. If you need a fairness opinion for an upcoming transaction, you go to someone who in that instance plays the role of a vendor. You get the opinion and are done.

With an advisor you want to develop a deeper, ongoing, and mutually beneficial relationship. You know each other’s strengths and weaknesses. You have a communication level where the advisor feels okay saying: “What were you thinking there?!” or “I think you might be looking at this backward; here’s a whole different explanation for what you just described.”

If you and an advisor do in fact mesh and work at the relationship, it can grow from the one-off engagement to a series of projects. You should be able to tell during that first project if the trajectory is headed in the right direction.

With some time and a bit of luck, the ongoing advisory relationship may turn into that of a journey partner. This builds on the advisor role, but with a deeper level of trust on both sides. It’s a go-to person for some of your toughest questions and challenges.

You can pick up the phone and call your journey partner, and ask: “Hey, Mary, I’m confronting a new situation, and I’d like to get your perspective and help on it.” Mary is not starting the consulting clock, because your relationship is deeper than something that’s measured in billable minutes. Instead, she might come back with, “Okay, but what do you mean by ‘help’? Is this help with a decision, or help with thinking through options?”

You might describe a situation where a group of managers are feeling threatened, and you need some creative solution in order to both translate strategy to action and create a win for middle management. The two of you might explore a number of options, and reach a few dead ends as well as viable scenarios. Your journey partner may even say, “I get where you’re going and what you need. We’re qualified for about 50% of this project, but you should talk to another firm about the areas we don’t specialize in; let me introduce you to them.”

A journey partner relationship is rare but absolutely worth pursuing because of the high-value insights and perspectives it can bring to your most difficult challenges.