4

Reason #1: Customer Success Stops Churn—The Silent Business Killer

Basic math tells us that as your company grows and your base of recurring revenue increases, the dollars of churn against that base get larger every month (in raw numbers), even if the percentage of churn stays the same. So you need more new business every month to replace the churn, which slows your growth. The bigger you get, the more your growth is slowed by the drag of churn.

Churn is like a weird kind of business-world gravity—an irresistible force—that's constantly pulling on your customer base. It's the silent, perpetual energy dragging the base down. Customers are exercising their right to leave more often than ever, thanks to the low-commitment pricing models and next-to-nonexistent switching costs brought about by the new cloud-based economy.

Remember what it used to be like when your clients would stay with you through thick and thin—and maybe the occasional steak dinner or sporting event? Yeah, those days are gone. Now you're earning your client's continued loyalty every single day.

But the next-level implication is where it gets interesting. One of today's key questions for business leaders is, “Which of my clients are at risk?”

Here's the hard truth: Any one of your clients could leave you at any time. In the long run, all of your clients are “red.” They're all at risk. Let's look at why that is:

- Your sponsor at the client will leave and the replacement may have experience with a competitor.

- Your client could have a bad experience with your team that changes everything.

- Your customer could switch business strategies and have less of a need for your offering.

- Your competitors could evolve faster than you are and be more compelling in a year or two.

Gainsight's Chief Evangelist (and co-author of Customer Success), Dan Steinman, likes to say, “The natural tendency of clients is toward churn.” And while this happens at the micro-level (client by client), it happens at the macro-level as well. We meet CEOs frequently who pride themselves on their “ninety-something-percent retention rate.” They like to say that churn doesn't affect them. They're out in space where gravity can't touch them.

Until it does: What we've found is changes in churn rate (like changes in velocity from gravity) accelerate over time. Then the cracks appear and alternatives improve. The early churns look insignificant. But then they snowball. All of a sudden, 95% retention is 50% or worse.

So what do you do? Fundamentally, leaders have been evolving their thinking from assuming that clients are “acquired” and committed for the long term to the idea that vendors re-earn their clients' business every day. In the long run, this means prioritizing and budgeting investments to ensure long-term client retention and success—instead of just assuming it will happen.

Churn is like gravity. If something goes up, you need to fight hard to prevent it from coming down.

CSMs are at the forefront of that fight against churn. As a result, improved gross retention is the first reason why companies tend to invest in Customer Success. Five years ago, companies would invest in building Customer Success teams once they realized that the churn they were experiencing was too high. It was a reactive measure to stem the tide, and the hired CSMs would enter what was effectively a firefighting role. Today, companies anticipate that churn will come unless it's proactively mitigated, so they design their organizations upfront to ensure strong gross retention rates.

What do we actually mean when we say “churn” and “retention”? Let's turn to more precise definitions.

Churn: How Do You Measure It?

Churn and Retention—which are inverses of each other—are not yet generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP) metrics. That said, the Customer Success industry has converged on a few calculations for Retention Rate. Your choice of calculation depends on whether your business has renewals (not all recurring revenue companies do) and your strategic focus.

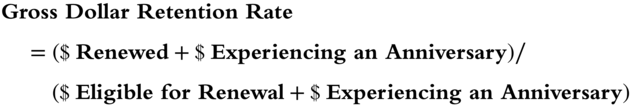

Type 1: Gross Dollar Renewal Rate

This is how you calculate it:

The difference between $ Eligible for Renewal and $ Renewed is the amount of Churn plus Downsell. Downsell captures a reduction in contract size, for example, due to the client not renewing a particular product module or not renewing some of their licenses. (This calculation obviously assumes that you have renewals in your business.)

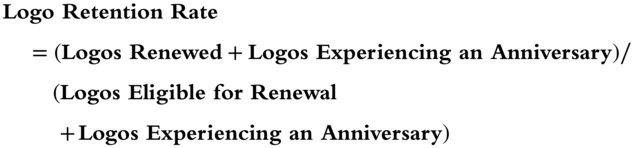

Type 2: Gross Dollar Retention Rate, Including Multi-Years

This calculation takes into account the beneficial impact of multi-year contracts by including the contracts that are experiencing an anniversary (i.e. essentially renewing by default) in the denominator.

This is the calculation that we recommend reporting to your board. Multi-year contracts are an important strategy for bolstering your recurring revenue and should therefore be reflected in this top-level revenue metric. (You can see that anniversary dollars, because they “renew” at 100%, will make this retention rate greater than your renewal rate from Type 1.) That said, if you are relying too much on multi-years to bolster your retention, because the clients that are up for renewal are not actually renewing at high rates, you should also pay close attention to the Type 1 calculation above.

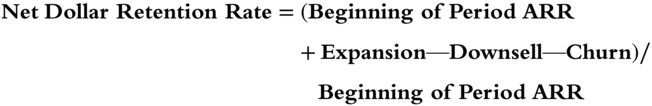

Type 3: Logo Retention Rate

Here we're capturing the logos that have renewed, rather than the dollars:

You likely won't be reporting this metric to your board, but your CS team should pay attention to it. Every logo, no matter how small, that churns your product represents another detractor on the market who can generate negative word of mouth and hamper future sales. (In fact, the smallest companies are often the most vocal about their poor experiences as clients.) Even if your Dollar Retention Rate is high, a low Logo Retention Rate can hinder your growth.

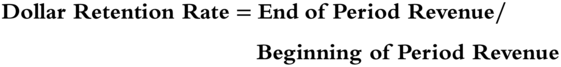

Type 4: Net Dollar Retention Rate

This is another dollar calculation, and it factors in the expansion of existing client contracts through upsell or cross-sell. Expansion can include the sale of new licenses or products, or the sale to new business units or teams within the client:

where Expansion, Downsell, and Churn are for the last 12 months.

Because Net Dollar Retention Rate allows a company to offset churn with expansion, it's by far the most popular metric reported in public SaaS company's filing documents.

Here's a related calculation:

In this calculation, Expansion can offset the impact of Churn and Downsell, potentially making your Net Churn Rate zero or negative, but it's still important to pay attention to churn on its own. We'll explore when to use Gross Retention and when to use Net Retention later in this book.

Type 5: No Renewals

This calculation is for businesses that do not have renewals. An example could be a diagnostics company that makes money when it sells tests, rather than at the time of a renewal:

for customers that existed at the beginning of the period (that's important because you don't want to count revenue from new customers; focus on the existing customer cohort). The period is 12 months. The numerator should reflect revenue from the last 12 months and the denominator should reflect revenue from the 12 months ending at the start of the period.

Because Ending Revenue could exceed Starting Revenue, this calculation works like a Net Retention Rate, which includes expansion, as we discussed above. In the case of the diagnostics company, a client may purchase more tests in the current period versus the previous one, or they may reduce the volume of tests or churn altogether.

So far in this chapter, we've discussed why churn matters (a business that's a leaky bucket can't survive) and what churn actually is (the leakage of dollars or logos). By now it's probably clear to you why companies would want to invest in reducing churn. But why does churn even happen in the first place? And therefore, what can companies do about it?

Why Does Churn Happen?

Venture capitalist, former CEO, and tech legend Ben Horowitz has written that if you ask salespeople why they lose deals, they'll always say, “It was the price.” Maybe they do it consciously, maybe they do it subconsciously, but by blaming price, they aren't blaming their product, their team, or themselves. Price is a safe, easy scapegoat.

In the CS world, we can lead ourselves into a similarly easy, non-blaming trap. Most of us have a “churn reason” field in our Customer Relationship Management (CRM) system and we attempt to code each churn so that we can report internally why the customer left. Having sat in on loads of churn reviews for dozens of companies, we've seen some other top reasons, besides price, for customer departures. They include:

- Sales expectations

- Competition

- Other

- Sponsor change

Seriously? What do you do with that info? Are all of those reasons equivalent? (Spoiler: No, they are not.) Is someone going to leave because of competition or sponsor change, but not both? Is sponsor change the reason they leave? Or is it a catalyst? Is sales expectations a convenient catchall? And how do we prevent future churns due to the “Other” reason?

We're not the only ones to think this way. Companies have been realizing they need to think more deeply about the why behind churn.

First, they are separating the root cause from the catalyst. You can do this with just about anything in life and it's good practice for applying this line of thinking to churn. Here's an example: Why did that soccer player blow out her knee? Was it because of the final fall you saw on TV? Or was it because of the 1,000 falls before that?

Similarly, CS teams are now breaking down their churn reasons into root issues and proximate issues. This is quite similar to marketing, where you might look at the last touch that caused a buyer to engage with you (maybe they filled out a form) and also previous touches (they watched a webinar). In Customer Success, root-cause issues might include:

- The product doesn't fit the customer need.

- The customer had a poor on-boarding experience.

- The product had a low adoption rate early on.

- The wrong people were at the client early on.

By contrast, proximate (final) issues might include:

- Sponsor change (which would have been fine if we'd had better adoption early on)

- M&A (which could have been fine if they were using the product actively)

- Competition (who wouldn't have been able to swoop in if the customer had been getting value)

- Price (which wouldn't have been an issue if the value were clear)

The proximate issue is often more readily apparent but outside of our control, whereas the root-cause issue is the real underlying problem and is typically within our control in some way. When companies start identifying root causes more consistently, they realize that they can reduce their churn. This feeling of empowerment propels companies to invest more in Customer Success—because it can result in a real revenue impact through churn reduction.

(As a side note, this is a wonderful example of how intellectual honesty makes more business sense.)

Nowadays, these root cause analyses almost always show that CSM execution isn't the only problem—and sometimes isn't the problem at all. Tomasz Tunguz, a partner at Redpoint Ventures, tends to see a few common root issues.

If an organization has high churn, there are typically three causes. It could be that the account executives oversell and then pass the account to the CS organization in a bad state. It could be the product doesn't work as advertised. Or it could be that the Customer Success Managers are ineffective. But the last one is rarest. It's uncommon to come across an organization that's running its Customer Success so poorly that you have massive customer churn.

That last point shows how far we've come in CS over the past five years, since earlier in this decade, massive churn due to execution issues was very common. Since then, companies have invested considerably in Customer Success both in terms of headcount as well as the implementation of best practices. That said, don't take your foot off the gas in CS. If you haven't achieved maturity in your CS operation, the gravity-like force of churn will inevitably result in leakage. What a shame to lose customers because of an execution problem!

Still, Tunguz's observations reveal that investing in churn reduction requires changes in other departments besides CS, a topic to which we'll turn in Part II of this book.

Summary

Simple math dictates that as your company grows, your churn increases in raw numbers—which means you have to bring in more new business every month to cover that churn. And although we all like to think that at least some of our client relationships are rock-solid, the truth is that every client is at risk of leaving. Given that the force of churn is as certain as gravity, companies have learned to invest in the foundations of their “house” of Customer Success in the same way that early humankind learned to create structures from sturdy materials.

Next, we'll look at a second reason why companies are investing in Customer Success: not only to plug the leaky bucket, but also to accelerate the flow of water into that bucket. In other words, companies believe that CS can contribute not only to revenue retention, but also to revenue growth.