Origins

It is an article of faith with me that a place consists of everything that has happened there; it is a reservoir of memories; and understanding those memories is not a trap but a liberation, a menu of possibilities. The richer the knowledge, the wider the options. Multiplicity is all. The only enemy is narrow, singular definition. And Sissinghurst, perhaps like any place that people have loved, is layered with these multiplicities. Even now, anyone who lives or works here soon develops an intense relationship to it, none of them quite the same, none quite distinct, none of them quite secure. Our different histories are buried and half-known but we all think we own the real thing, or at least want to. It is a place drenched both in belonging and in the longing to belong.

I always knew that its foundations were in clay, silt and sand – clay at the bottom end of the farm, through which the Hammer Brook runs, sand on the higher ridges above it and silt scattered through all of it. The clay is late land, always lying cold and reluctant, heavy and wet. It is where the fertility lies and where cereals do have some kind of a chance, at least with modern equipment. Hops, which are hungry plants, were always grown down on the heavy land by the Hammer Brook. In summer the clay is capable of turning to concrete – and then dust – as soon as the sun starts to shine. In winter, it makes for thick and cloggy ground. If you walk across one of the clay fields when it has been ploughed, it gathers in lobed elephantiasis clumps around your boots. Teams of six or eight oxen were always needed to pull a plough through these fields, and when Queen Elizabeth and her court came here in August 1573, Lord Burghley, who was with her, said it was worse than travelling in the wilds of the Peak District. Even in midsummer the roads were ‘right deep and noyous’. If heavy goods had to be brought in – in particular the bells for the churches – or timber taken out, the oxen laboured for days. I asked a farmer who had worked all his life on the clay lands to the north of here what his farm was like. ‘Not boy’s land,’ he said.

Clay, born in the wet, remains a friend to it. Surface water turns into streams. The streams cut away at the clay country, leaving the better-drained sand and silt standing proud as ridges. It is that physical difference which has cut the physiognomy of Sissinghurst. High is open and relatively dry; low is wet, secret and thick with clay. A hole dug in the clay ground here becomes a pond. No lining is needed. Clay smeared with a digger-bucket seals itself. In the 40,000 acres of pure clay lands to the north and east of Sissinghurst, I have counted on the map very nearly four thousand ponds. They are usually no more than the holes where farmers have dug, more often than not for the slightly limy clay called marl, which was used from the Middle Ages onwards to sweeten these generally acid soils. The holes have simply filled with water, but each has its character: overhung with ancient oaks, the outer fingers of their lower branches dipping into the dark surface; smartened in the garden of a newly gentrified farm; or eutrophic, clogged in the middle of an arable field with all the green slime that comes from too much fertiliser draining into it.

The sand is the clay’s opposite: thirsty, capable of drying out in anything resembling a summer, without the nutrients on which good crops rely but making for easier and lighter country. Clay and sand are the polarities of the place, although in reality the situation is not so clear cut. The two principles mix and muddle across the whole of Sissinghurst. The soils roam from silty sands and sandy silty clays to silty clay loams and on to solid clay itself, perfect for the bricks that were made at least since the eighteenth century in the Frittenden brickworks just to the north of Sissinghurst. Patches of lightness appear here and there in the middle of heavy fields, and sudden wet clay sinks can be found in the middle of soils that are otherwise good and workable.

Only here and there do the two extremes appear as themselves. On the hill above Bettenham, there is an old sandpit, perhaps where the sand for the mortar used in building Sissinghurst was dug, and where now you can find little flakes and pebbles of the sandstone pulled out by the rabbits. It also appears in another small pit in the Park, just next to the old road going south, a friable, yellowish stone which crumbles between your thumb and finger. Here and there are thin iron bands within it. But play with a pebble for a moment and all you are left with is smooth, talcum-like dust on your skin. There are small pieces of this stone, included as yellow anomalies, among the bricks next to the entrance arch at Sissinghurst. On the high dry ridge at the western edge of the farm, there is a field still called Horse Race because that is sandy, well drained and had the best going for the gentry in the seventeenth century and the officers of the eighteenth-century militia who used to race their horses here up until the 1760s. But it is not as building stone that this sand is significant. It is for the lightness it has given some of the soils here, far lighter than many places in the Weald.

At the top of the big wood there is a light, almost purely sandy patch, where a big group of sand-loving beeches grows. They are the most climbable trees at Sissinghurst, and not one of them appears down in the damp clay land. A third of a mile away, at the other end of the ridge, a cluster of sand-loving Scots pines was planted here in the 1850s by George Neve, the improving Victorian tenant. It was here that my father, as an anxious young man in the 1940s, proposed to the beautiful and entirely alluring Shirley Morgan, the only girl he ever loved and who would never accept him, despite a campaign lasting years. It was a well-chosen spot: if he had decided to lay her down on the damp sticky clay soils at the bottom of the farm, he wouldn’t have had a chance. At least he got the geology right; but geology wasn’t enough. How much easier it must be for men who live on perfectly drained, downland turf, with endless vistas across their spreading acres, to convince the girls they love. My poor father could only point to distant views scarcely visible between the trunks of the surrounding trees. Over there, on a good day, he would have said, you can almost see the tower of Canterbury Cathedral. It wasn’t enough; Shirley married a brilliant and handsome marquess whose beautiful house in North Wales has a view across its lawns of mountains and the glittering sea. My father never ceased to love her.

Sissinghurst, in its roots, is a little second rate. This part of Kent has never been smart England, and its deepest of origins, the sources of its own soil, are decidedly murky. I love it for that. This is ordinariness itself: no volcanoes and no cataclysms, just a slow, deep gathering of what it was. The first moment when Sissinghurst came into being, when the stuff you can now hold there in your hands was there to be held, was about 120 million years ago. Britain was at the latitude of Lagos. Dinosaurs walked its river valleys, and a range of old and stony hills lay across the whole of England to the north. Forests of horsetails and giant ferns shrouded the valley slopes. Two steaming rivers flowed south out of those hills, their tributaries grinding away at the old rocks of which the hills were made. The rivers ran fast and carried with them a load of coarse-grained sand. As they emerged from the hills, just south of London, they flowed into a huge and swampy delta, covering perhaps 30,000 square miles, stretching from here far to the south of Paris, a dank, tropical place with many soft islands within it. Here the current slowed and dropped the sand in wide banks across the estuary. These, in their origins, were the sands on which Shirley Morgan lay immaculate and the officers of the Hampshire Militia, the young Edward Gibbon among them, raced their sweating horses.

As the rivers coming south from the uplands in Hertfordshire and Essex wore away at their hills, they slowed and became sluggish, carrying now only the finest of grains. What had been delta sands turned to thick grey mineral mud. The grains settled closely together in a gluey morass, a brackish and hostile place. It was a fossilised quagmire, impenetrable, a trap for anything that wandered into it, burying entire trees and whole animals, a graveyard of gummy secrets. This was the origin of the Wealden clay. Of course, my father didn’t try to kiss Shirley Morgan there. They would have sunk into it, slowly disappearing, as if into the jaws of an insect-eating fungus.

When I was a boy, I used to play with the clay in the summer. You could dig it out of the side of the lake banks, wet and slithery in your hands, your fingers pushing into the antique ooze. If you held a small ball of it in your fist and wetted it and squeezed it, two slimy snakes of clay, like a patissier’s piping, would emerge top and bottom, curling, ribbed, while their miniature cousins came out between the joints of your fingers. It felt like ur-stuff, stuff at its most basic, as good as dough or pastry, squeezable, makable, lovable. Occasionally, we moulded it into pots, one of which I still have sitting on my desk, unglazed and unbaked, a rough lump from the basement of existence. Your shorts and shirt after one of these mornings would be unwearably filthy, your hands and legs washable only under a hose.

This was the clay which in the sixteenth century gave modern Sissinghurst one of its essential substances and colours: brick. No record survives of the great brick building programmes here, either from the 1530s or the 1560s, but there can be no doubt that the clay for the pink Tudor and Elizabethan palaces at Sissinghurst came from the stream valley just to the south. When Vita and Harold wanted to put up new garden walls in the 1930s, they commissioned bricks from the Frittenden brickworks only a mile away on the other side. But the bricks of those walls never looked right: too brown, without the variable, pink, iron-rich, rosy flush the sixteenth-century builders had found. Even from a mile away, the brick Vita and Harold used was obviously not from here. It was one of their mistakes.

If the Sissinghurst process followed the pattern elsewhere in the Weald in the sixteenth century, the clay itself would have been tested and selected by an expert, a travelling brickmaker. In the autumn or early winter, gangs of labourers would then have dug the raw clay out of the valley and spread it out over what are now the Lake field and Long Orchard, so that autumn rains could get into the lumps and the frost split them. All winter the clay lay there on the fields, a dirty orange scar, like the embankment for a railway or bypass under construction. In the spring, the clay was rewetted and then, with more gangs of day labourers, trampled underfoot. Raw clay is full of little stony nodules. If they are left in the clay when it is fired, they overheat and split the bricks. For weeks, probably in large wooden troughs, the clay was kneaded and the little stones removed so that the brickmakers were left with a smooth and seamless paste which could be pushed into wooden brick-sized moulds, usually here nine inches long, four wide and two deep, the long, thin, smoked-salmon sliver-shaped bricks of sixteenth-century Sissinghurst. I remember seeing moulds of exactly that form in the Frittenden brickworks when I was a boy, but they have disappeared now. The clammy raw clay bricks were then turned out of the moulds and left to dry in stacks for a month. In Frittenden there were long, open-sided wooden sheds for this, with oak frames and tiled roofs, but the scene in the fields of Elizabethan Sissinghurst would have been more ad hoc than that: bricks drying in what sun there was on offer. The whole process would have relied on a good fine summer.

Only at the end of the drying, when the bricks would already have developed some of the cracks and wrinkles you can still see in Sissinghurst’s walls, would they be fired. Specialist brickmakers would arrive again, hired for the purpose, and build temporary ‘clamps’, clay-sealed kilns in which the bricks were baked in a wood fire. It was a local and not entirely consistent process. Those bricks that were at the windward end of the clamp were more thoroughly fired than those downwind. The clay itself had wide variations in iron content. Different clamps, some with drier timber than others, some even using brushwood, burned at different temperatures. And so the flickering pinkness of Sissinghurst’s walls emerged from the ground, everything from red to black, the near-white pink of flesh to the pink of camellias, wine red, apricot, even where it is rubbed a kind of orange, but in sum, across a whole wall, always with a rosy freshness, a lightness to the colour which denies its origins in damp and fire, and scarcely reflects the whole process, the transmutation of an ancient eroded swamp. Not that the Elizabethans would have liked the variability. They would have admired and required precision and exactness. It was only because there was no stone here with which to build that they turned to the clay. The idea of bringing any quantity of stone from the quarries in the greensand ridge eight miles to the north was unthinkable, in time and expense, on the wet clay roads. Clay ground, thank God, meant a brick house, a subliminal joining of a high-prospect tower to the ground it surveys.

Even since human beings first arrived here, 750,000 years ago, seven ice ages have come and gone, driving the people, the animals and the plants far to the south, to their refuges in the warmth of southern Europe, and leaving this place, if not ice-bound, at least a frozen tundra, bleak and treeless. If I shut my eyes, I like to see it then, just at its moment of emergence, at the end of the last ice age, about twelve thousand years ago. It is a rolling windswept plain, continuous into Europe. Nothing coats the horizon but the grasses and the moss. There is cold to the north. Storms cross it in winter. In summer, as it does the steppe, the sun dries and burnishes it, a Ukrainian pelt concealing the earth. Ten thousand years ago, the average July temperature in Kent was already in the mid-sixties Fahrenheit. With that warmth, into this huge savannah, more developed forms of life come rippling up in the wake of the retreating cold. First, the great herds of grazing animals, what may appear now like a North American scene but was indeed the case in northern Europe as the ice withdrew. Roe deer, red deer, no bison but the huge wild cows called aurochsen (of which the last, a Polish cow, died in 1627, and one of whose horns is still used as a communal drinking cup in a Cambridge college), elk or moose and herds of wild boar: all of these in their hundreds of thousands thrived on the great grassy treeless plains, where the wolves and lynxes pursued them. Bears would have fished for salmon and trout in the Medway and the Beult, the Hammer Brook and its glittering, unshaded tributaries. Foxes, cats, martens, otters and beavers would all have been making their way up from the south, a spreading tide of appetite and complexity.

A sense of openness and fullness would have been there at the very beginning of Sissinghurst. Even now, wild animals in these situations are not afraid. The first European visitors to the great American plains found the herds wandering up to them with fearlessness and curiosity, a look in the eye from a stag, a straight sniff from a moose. Charles Darwin killed a fox on the South American island of Chiloe in 1834 by walking up to it and hitting it on the head with his geological hammer. Those paintings of Douanier Rousseau’s in which wild animals put their noses into the faces of men asleep on the ground are not romantic fantasies but descriptions of how the world once was. Eden was a reality here. And the first domesticated animals accompanied the men. As Sir Francis Galton, the Victorian polymath and cousin of Charles Darwin, described in 1865, the children of the native Americans kept bear cubs as their pets. All those paintings on cave walls clearly bear witness to animals seen close up and in numbers. A drawing on ivory from the Pyrenees of about ten thousand years ago shows a horse’s head in a harness. People and their animals walked up into the oceanic widths of the grassy savannah. This moment is the oldest of the Wealden folk memories. I have my grandmother’s copy of the first great book written about Kent, William Lambarde’s Perambulation, published in 1570. She must have had it in the 1920s when writing The Land, her long Virgilian epic on the Weald, sidelining in it the passages she liked. The Weald, Lambarde had written, and she marked, ‘was nothing else but a Desart, and waste Wildernesse, not planted with Towns or peopled with men, as the outsides of the Shire were, but stored and stuffed with heards of Deer and droves of Hogs only’.

The birds came with them and with the birds the trees. In the pollen record, those trees whose seeds are dispersed by birds are the first to appear in the wake of the shrinking ice. Snow buntings, the Lapland bunting and the shore lark all now spend the summer in the tundra on the edge of the Arctic and the winter farther south. They would have carried the first tree seeds up to sub-arctic Sissinghurst, perhaps the blackthorn and hawthorn, whose berries they would have eaten in the Dordogne or the Lot and would have dispersed here to make the first shrubby patches in the grasslands. The nutcracker has been found carrying hazelnuts ten or twelve miles from the trees where they picked them up, and perhaps, ahead of the wind, the nutcrackers were responsible for the big hazel woods which were the first to grow on the grasslands here. A thousand miles at ten miles a year takes only a century.

Quite slowly, with the help of the warm south wind, the wood thickened. First, the willows, the pioneers, set up in the damp patches, the fluff of their seeds drifting up in the summers. By 8000 BC the birch had arrived. Five hundred years later, the oaks came, their acorns almost certainly carried north by jays. The elm had also come, growing only on the dry land, not down in the damp of the clay. (‘The oak unattended by the elm,’ J. M. Furley, the great nineteenth-century historian of the Weald, wrote, ‘betrays a soil not prized by the agriculturalist.’) By about 6000 BC alders had colonised the stream margins, where they are still to be found, reliant on the water flowing steadily past their roots. The ash came at the same time. Not until about 5000 BC were there any beeches here, and then only, as now, on the drier hills. The hornbeam came even later and the chestnut not until the Romans brought it.

All of them had come north from their ice age refuges in France, wandering up on the wind into the increasingly friendly environments of Kent. It is like the cast of a play coming on to the stage and finding a seat there. As you walk through the woods and stream margins of Sissinghurst today, it is of course possible to listen to the ensemble, just to drink in the flecking green light of the wood in summer, but you can pick out individual lines of the instruments too and find here now, perfectly articulate if you listen for it, the story of their arrival.

The thorns were the early pioneers. In a rough and neglected sliver of Sissinghurst Park Wood, where some giant alder stools have overgrown themselves and crashed down on to the wood floor, leaving a hole in the canopy behind them, blackthorn has invaded to make a thick and bitter, self-protective patch. The long sharp thorns are poisonous. If one of them pricks you and breaks off in your flesh, the red-flushed wound festers for days. The blackthorn patch is everything the word ‘thicket’ might imply, tangled into a hedgehog of denial and involution, clawing at itself, a crown of thorns thirty feet across. A big hawthorn standing coated in mayflower in a hedgerow is one thing – and well-grown thorns certainly make outstanding firewood – but the essence of a thorn is this thickety resistance to all outsiders, a miniature act of self-containment which the medieval English called a spinney, a spiny place, designed to exclude.

As children, we were always taught that you must try to sympathise with the spiky and the spiny, to understand what it was that did not allow them the open, displaying elegance of the beech or the confidence of the oak. Why are thorns so bitter? What can be the point, in such a calm English wood, of such unfriendliness? You feel like asking them to relax, even if relaxation is not in their nature. But everywhere in the woods at Sissinghurst there is one repeated clue to this foundation-level exercise in tree psychology: at the foot of almost every oak there is at least one holly nestling in the shade. Why? Why is the spiky holly drawn to the roots of the oak? What sort of symbiosis is this? But the question, it turns out, may be the wrong way round.

Why does the oak live with the holly? Because the holly, when they were both young, looked after the oak. Its spiky evergreen leaves protected the young acorn seedling from the browsing lips of the ever-hungry deer. The oak had a holly nurse, and only after a while did the young tree outstrip the protector that now shelters in its shade.

That too was the role played by the early spinney thickets. In an England filled with roaming herds, new trees needed to adopt one of three or four strategies to outstrip the nibbling lips. Either a spiny blanket which would mean they weren’t eaten themselves. Or sheltering within someone else’s spiny blanket, so that by the time they emerged from it they were big enough not to be eaten. Or, like those other pioneers, the willows, growing so fast that at least one or two of you could outstrip the ubiquitous mouths. Or finally, like the birch, just as much of a pioneer of new ground as the willow or the thorns, colonising new areas in such numbers that at least one or two would escape the enemy. The browsing beasts were at war with the trees and the tree strategies were clear enough: hunker down (the thorns); borrow a friend (oaks, elms, beeches and ashes); keep running (the willows); or blast them with numbers (the birch).

Every one of these post-ice age theories of defence – spike, cower, rush or proliferate – is there to be seen in the Sissinghurst woods today. A few years ago, one of the great beeches on the high ridge of the big wood collapsed in a gale. Nothing was more shocking to me than to find it one autumn self-felled and horizontal, its stump a jagged spike ten or twelve feet high, looking more ripped than broken, as if someone had taken a pound of cheese and torn it in half. My father always used to bring us here in springtime when we were small and lie us down on the dry bronze leaves and mast below the tree. The new leaves sprinkled light on our faces. Each leaf was like a spot of greenness, floating, scarcely connected to the huge grey body of the tree. My father always said the same thing: how wonderful it was that this duchess, each year, dressed herself like a debutante for the ball. I cannot now look at a beech tree in spring without that phrase entering my mind.

Later, I climbed it often enough, chimneying up between its forking branches, avoiding the horrible squirrel’s dray in one of its crooks, finding as you got higher that limbs that had seemed as solid as buildings farther down started to sway and shift under your weight and pressure. Then coming up into the realm of the leaves, as tender as lettuce early in the summer, acquiring a sheen and a brittleness as the months went on, until at last, in the top, like a crow’s nest in a square-rigger, where the branches were no thicker than my forearm, I could look out over the roof of the wood, across the small valley, to the Tower, whose parapet half a mile away was level with my eye and where the pink- and blue-shirted visitors to the garden could be seen by me, while I knew that to them I was quite invisible.

Now the whole tree was down. Its splaying limbs had been smashed in the fall and lay along with the trunk like a doll someone had squashed into a box. I could walk, teeteringly, the length of the tree, as if I were a nuthatch whose world had been turned through ninety degrees. Even then, the beech started to rot where it lay. As it did so, something miraculous happened: in the wide circle around the beech’s trunk, to which its multilayered coverage of leaves had denied light, nothing in the past had grown. Now, though, the light poured in, and in that circle hundreds and hundreds of birch trees sprang up, a dense little wood of rigid spaghetti trees, a noodle wood, without any great dignity or individual presence but extraordinary for its surge and hunger, opportunists, like pioneers pouring off their ship into a new and hope-filled land. Within their new wood, the body of the beech lay as a mausoleum of itself, vast and inert, an unburied colossus, yesterday’s story, no more than a reservoir of nutrients for the life that was so patently already coming after. The birch surge was, in its way, just as much as the thorn thicket, or the oaks sheltering in the embrace of the holly, or the romping willows on the banks of the lake, a vision of what happened here after the ice age was over, when the cold withdrew, and trees reclaimed the country.

As much as the clay, the trees are at the heart of Sissinghurst. To the south and west of here, the woods of the High Weald make up a broken, parcelled, varied country, thick with tiny settlements and ancient names, all of them in their own nests of privacy, tucked in among the folds of the wood on the hills. It is still possible, even today, to walk for eighty miles in a line going west from Sissinghurst – if you are careful and pick your path – without leaving woodland for more than a quarter of a mile at a time. Not until you reach the Hampshire chalk at Selborne does open country defeat you. Weald means Wald, the great wood of England, and although it has been eaten into and nibbled at for at least fifteen centuries, and perhaps for more like fifty, it persists. It is the frame of Sissinghurst, the woods, in Kipling’s words, ‘that know everything and tell nothing’.

Wood to Sissinghurst is like sea to an island. Everything in the Weald, in the end, comes back to the wood. Sissinghurst’s parish church, at least until the nineteenth century, was at Cranbrook, about two and a half miles away, a short bike ride. It became an intensely puritan place in the sixteenth century, and the feeling in the church still reflects that: big clear windows, a spreading light, the clarity of revelation. But in the church, miraculously preserved, are the remains of an earlier and darker phase. On the inner, east wall of the tower are four ‘bosses’ – large, carved wooden knobs, originally made to decorate the intersections of beams in the roof high above the church floor. These are from a late-fourteenth-century chancel roof which was replaced in 1868. They are some of Cranbrook’s greatest treasures. Each is cut from a single fat dark disc of oak, a yard across and a foot deep, sliced from the body of a timber tree. The carving takes up the full depth of the disc so that there is nothing shallow or decorative about the form. Most of the oak has been chiselled away, leaving only the vibrant, mysterious forms. These faces are the trees speaking. The trees have been felled but here they grow again.

Each of the four bosses has a different atmosphere, a different reflection of the nature of the wood, and of the human relationship to it.

Man at ease in nature

There is a conventional, if smiling human face, a young man, wearing a padded hat and a headcloth, surrounded by a mass of curling leaves, a wide border to the face, with no interpenetration between figure and tree. It is, perhaps, an image of reconciliation, of an easiness with the facts of nature, a civilised man (or perhaps a woman?) settled in his bed of vegetation, like half an egg resting on its salad.

Man troubled by nature

The second, which is aged, bearded and broken, as if the boss had fallen from the chancel roof on to the stone floor of the church, was clearly similar, a face with leaves, but more troubled, an arch of anxiety across the bearded man’s brow, a feeling that in the luxuriance of his beard there is some osmosis across the human–natural barrier. Already here, the civilised man is sinking into (or is it emerging from?) the vegetation that threatens to smother him.

The other two come from somewhere still deeper, wild and savage things from a world that seems scarcely connected to Christian orthodoxy, let alone to the neatness of modern Cranbrook going about its shopping outside the door. These are the wood spirits that have emerged from the primitive Weald itself:

Nature as threat

The first is a huge, near-animal mask, at least twice the size of a human face, with goggle eyes and an open mouth, a face of threat and terror. Between its lips, roughly hewn, uneven peg teeth grip the fat, snaky stems of a plant, which is clearly growing from this creature’s gut and from there spewing out into the world. Its chiselled tendrils engulf the head, branching around it, gripping it and almost drowning it, as though the figure were not the source of the wood power but its victim. The whole disc looks like a hellish subversion of a sun god: not a source of emanating life and light but a sink of power, dark and shadowed where the sun disc gleams.

The fourth of the Cranbrook bosses is the most intriguing. The same net of leaves, which are perhaps the leaves of a plant that hovers between an acanthus and a hawthorn, crawls all over the surface of the boss, but without regularity, a chaotic and naturalistic maze of leaf and hollow, mimicking the unregulated experience of a wood itself, highlight and shadow, reenacting the obstruction and givingness of trees. Within this vivid maze of life, there is something else, a body, winged apparently, with a giant claw that grasps a stem, and beyond that the full round breast of a bird. There is a head here, perhaps of a dragon, curled round to the top and difficult to make out, a presence, neither slight nor evanescent, both solid and unknowable, the wood bird/dragon, which does not even give as much as the green man, with his terror-explicit face and strangeness-explicit eyes.

Nature as the maze of life

These four great Cranbrook bosses were almost certainly paid for by the de Berhams, the family living at Sissinghurst at the end of the fourteenth century, when Cranbrook church was embellished, and whose coat of arms was carved on the west face of the church tower. In their bosses, there is a buried and schematic sermon on our relationship to the natural world. The set of four presents four different visions in a sort of matrix, two human, two natural, two good and two bad: a sense of ease among the froth of vegetation (human good); anxiety at its power (human bad); the bird/dragon half seen in the obscuring leaves (natural good); and the peg-toothed wood god grinning in the dark (natural bad). There seems to be no ranking here. Each is equal with the others. Together they are a description of how we are with the natural world (delighted or threatened), and how it is with us (mysterious and beneficent or obvious and cruel). Nothing I have ever seen has made the wood speak quite like this.

Of all the trees that this part of the world was in love with, none was more constant than the oak. In the great rebuilding of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, oak played a constant part. The hundreds of big Wealden houses on the farms around here are always crammed with as many oak studs in their façades as they could manage.

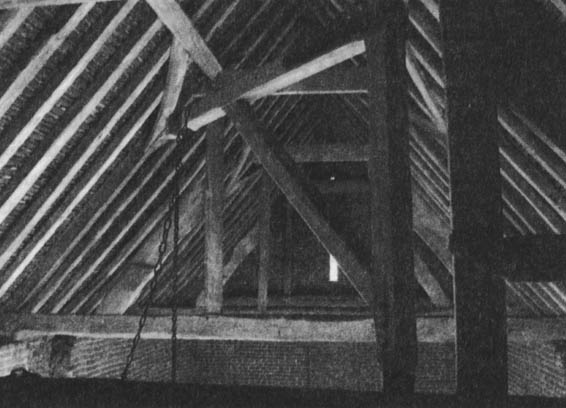

At what remains of Sissinghurst itself, which is a brick house, consciously set apart from the yeoman timber-framed tradition around it, the timber still shapes the interiors. All my life, lying in bed in the morning or last thing at night, I have stared up at the oak joists and tie beams of its ceilings. In the five hundred years since they were put up there, the oak has lost the orange-brown tang that it has when new and paled to a kind of dun suede, dry and hard, with a sort of suavity to it. There is no way you could bang a nail into this oak now, but it makes no display of its strength. It lies above you as you lie in bed, the grain visible along with an occasional knot, the edges as clean and sharp as the day they were cut. I have slept in every bedroom in the house at different times, and each has its different quirks and wrinkles. In some you can see where the sawyers using a doubled-handled saw made their successive cuts. A man stood at each end of the saw, one above, on the timber itself, the other, the underdog, in the pit beneath him. Each downward swoop was followed by an upward cut, and each cut moved the saw a quarter or a third of an inch along the joist. Each of those cuts is visible now in little ridges, not quite aligned, some almost on the vertical, some more on the diagonal, where one or other of the sawyers ripped an extra bit of energy into his stroke. The timbers look like a roughened bar-code, an account of two men at work one Elizabethan morning.

Oak sack hoist, trusses and rafters of the Elizabethan barn

Until recently, it was thought that the original wildwood, the wood of England before man began to change it, was a huge and continuous cover of trees, the crown of each tree meeting those of its neighbours for hundreds of miles so that a squirrel could run from Dover to Ludlow or Penzance to Alnwick without once needing to touch the ground. Universal and mysterious gloom prevailed in this ancient picture. Occasionally a giant tree would crash to the ground, it was thought, and light would come down to the forest floor, but for the most part life was said to crawl about in a romantic vision of everlasting shadow.

All of that, it now seems, may be wrong. In the last few years new thinking, particularly by the brilliant Dutch forest ecologist Frans Vera, has begun to challenge this idea of the ubiquitous, closed forest of the ancient world. According to Vera’s ideas, the ancient Weald, the sort of landscape that people would first have found when they came to Sissinghurst, may not, strangely enough, have looked very different from the Weald as it now is. If I walk out from Sissinghurst, across the Park, into the wood and out again into the pasture fields beyond it, where the oaks grow spreadingly in the light, I may well be walking through a place whose condition is rather like it was five thousand years ago.

If you take your bike and ride north from Sissinghurst, about seven miles across the clay flatlands of the Low Weald, past a succession of fifteenth- and sixteenth-century oak farmhouses, you come beyond Headcorn to the first rise of the Greensand Hills. Farmhouses, farm walls, barns and piggeries all start to turn here into the pale grey ragstone of the hills themselves. Just north of Headcorn, where the old road is cut deeply into the slope, you climb to the village of Ulcombe. From here you can look back at Sissinghurst from a place on its own skyline. The Weald lies blue and glossy in front of you. Beyond the ground at your feet, there is nothing but trees. I scanned the whole horizon. In the binoculars – it must have been five miles away – I saw what I hadn’t spotted with the naked eye: a kestrel hanging and fluttering in the summer air. Its body was quivering in the eyeglass from the rising heat, a black dot buried in the distance, making its own survey of the land. Beyond the kestrel’s body, I could make out the ridges of the Weald, one layer of wood after another, but scarcely a field and no buildings, except, very occasionally, a church tower. There was no hint of modernity, nor from this height even the sound of traffic. Only, far to the south-east and grey with distance, like islands seen from out at sea, the huge blocks of the Dungeness power stations on the Channel coast, and the necklaced pylons strung towards them like toys. Otherwise only the heat, the dot of the kestrel and the blue of the wood. Even with the binoculars, I couldn’t make out the Tower at Sissinghurst, but the avenue of poplars going down from the herb garden to the lake, planted by Vita and Harold in November 1932, stood out clearly enough, almost the only verticals in the continuous rounded swells of the oaks.

The view from Ulcombe is a vision of the great wood of England. All the hedgerow oaks in the Low Weald come together to give an impression of uninvaded woodland. It is a view that might have confirmed the old theories of the solid, unbroken canopy of the Weald. Now, though, intriguingly for the later history of Sissinghurst, it seems that this picture of the dark, continuous ‘closed’ forest of folklore may not be the whole story. The critical factor, for Frans Vera and those who follow him, is the large herds of grazing animals. What effect would they have had on the ability of trees to reproduce themselves? Would they not have nibbled the seedlings even as they emerged? Added to that is the strange anomaly of the large amounts of oak and hazel pollen that have been found trapped within ancient muds at the bottom of lakes and ponds. Neither oak nor hazel can reproduce itself in shade. They need plenty of light to establish themselves as trees. If the forest remained dense and dark, with the canopy closed, how come there were so many of these shade-intolerant trees?

Vera’s answer combines an understanding of the nibbling mouths with all the defence strategies the trees employ to resist or evade them. The Vera forest is a mosaic of thorny patches in which young saplings are growing; open, park-like savannah in which spreading, many-branched trees stand over well-grazed pastures; fringes of nettle, garlic, sorrel and goosefoot; and in the centre of the spreading woods places where the trees have aged and died and grassland has re-established itself, with its butterflies and all the birds of the woodland edge. It is not unlike the Park at Sissinghurst now, fringing on to the wet alder and oak wood, with thorny patches here and there (which we call hedges) in which the young oaks spring up, protected by the thorns and looking for the light. If Sissinghurst’s well-managed parklands were abandoned, and the grazing mouths withdrawn (by a wolf, say, or lynx), then blackthorn, hawthorn, guelder rose, wild apple, pear and cherry, together with lots of hazel, would all emerge, to make buttons of young, scrubby wood. The whole place would be in slow and gradual flux under its ancient tension of grazing mouth and germinating tree: not a constant and continuous place, but somewhere in movement, a shifting of high woodland from one place to another, an opening of grassland, a recolonising of it by scrub.

Seen from a time-lapse camera, suspended over it in a balloon, the country flickers and shifts. The herds come and go, the patches of woodland emerge as thorny thickets and spinneys, become high, leafy canopied oak wood and collapse in time, the animals moving in again, the grassland emerging, the buttercups flowering in the flush of summer. There were beavers here then, and when beavers build dams in streams and small rivers, the roots of the trees rot and the forest collapses. If the beavers then leave, their dams break and the pools empty. In place of the drained pool, a grassy meadow develops and elk and deer come in to graze it. When Western colonists first went to Ontario they often found beaver meadows up to a hundred acres across and used them to make hay for their own cattle. So perhaps this too was happening down in the valley of the Hammer Brook, beaver dams and beaver meadows, the opening of wonderful damp, grassy glades where the herds of deer would come to graze.

I know that for others, certainly for people who have come to work at Sissinghurst and to make their lives here, its beauty lies in its fixity, in its resistance apparently to modernity, and as a place that was reassuringly still and even perfect. Why did I not share in that?

Perhaps, I came to realise, because it allowed us a place here too, because a focus on vitality and change, which may look like a rejection of the past, is, if set in this other framework, in fact a continuation of it. It might re-establish at Sissinghurst a sense that this was not a shrine or a mausoleum, but a long-living entity, far older than any one ingredient in it, of which self-renewal was part of its essence.

The Weald has never been the best or richest of lands. Throughout human history, the part of Kent that has seen the greatest development, the most people, money, roads, cities and grandeur, has been the strip of land in the north of the county, between the North Downs and the marshes that run along the south shore of the Thames estuary. Even at the very beginning, that would have been the prime land. It was easy to reach from the sea. Endless little creeks run up into it from the estuary shore. Travelling there, on lighter soils, would have been far easier than in the Weald. The soils were good there. It is one of the deep structures of Sissinghurst’s history that it is a long way in from that coastline and set apart from that richness.

Even so, at the very beginning, the wild animals of the great wood would have been a draw, and the first signs that people came to Sissinghurst are now in Cranbrook Museum. Gathered in a glass case are the earliest human artefacts from this part of the Weald, flint hand axes and knives found now and then by chance in ditches and postholes, or turned up by the plough. A cluster of them appeared when Cranbrook School made its playing fields. A mile to the south of here, in a field at Golford Corner, a large Mesolithic flake was found which could have been a pick, perhaps belonging to a group of hunters pursuing the deer five or six thousand years ago. Some of the flints had yet to be made into useful tools or weapons; spare parts, elements of a repair kit. One or two had been chipped into blunt ‘scrapers’, used for separating flesh from skins. I have handled these stones at the museum, and one arrowhead in particular is a perfect thing, made of flint that the huntsman had brought here from the chalk downland to the north and then dropped or abandoned, who knows why. Its edge, scalloped to sharpness, each chipping like part of a little fingernail dished out of the flint, can still cut a slice in a piece of paper. There is nothing primitive or crude about it. It remains as honed as the day it was made.

Even so, these stones are at best fragmentary memories, half-whispers from the distant past, but they do at least articulate one thing: people were here. And they brought something with them. They were here for a purpose, and the fact they were here must mean there were animals in the Sissinghurst woods worth pursuing. How had they come? How did their life relate to this geography?

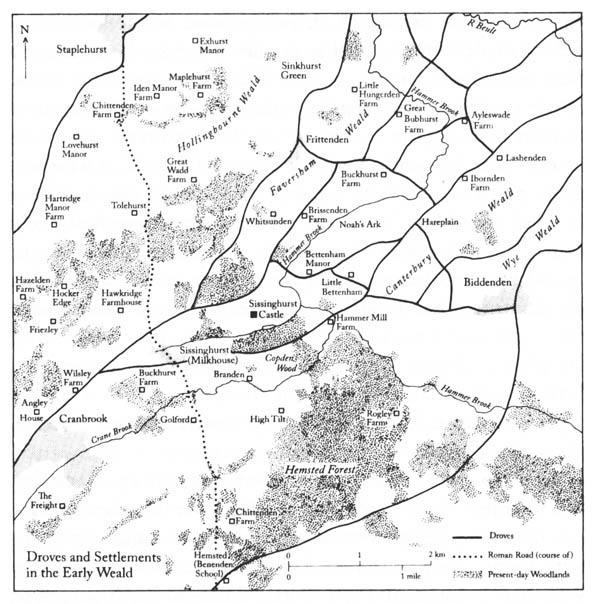

If you look at a map of the lowland that lies to the north-east of Sissinghurst, the 25,000 acres taken in by the view across the farmland of the Low Weald from the Tower, what you are looking at is the section of country that connects Sissinghurst to Canterbury and all the riches of the light, good soils in north-east Kent. Remove the villages and the farms, the railway and the Victorian toll road, and look for a moment only at the arrangement of the lanes. A pattern emerges. Quite consistently, over a front about seven miles wide, the country to the north-east of Sissinghurst is aligned around a set of long, sinuous but almost parallel lanes which snake across the Low Weald, each separated by about three-quarters of a mile from its neighbours. Sometimes the lanes visit the villages, but more often ignore them and slip onwards, across the clay lowlands. Farms are usually latched on to the lanes, but not always, and quite often little side routes diverge to a settlement, while the main drive moves on as if it had another motive beyond visiting the local and the immediate.

In the Dark Ages, 1,500 years ago, these lanes undoubtedly became the drove roads of early English Kent, the routes by which settlements in the Weald were connected to the more established manors in the rich lands around Canterbury to the north-east, but there can be little doubt that they are far older than that. If you bicycle along them or even drive along them in the car, the sensation is quite different from driving along most lanes in England. They have an air of seamless continuity. There are no blind corners. You swerve across the miles with an extraordinary, liquid authority, gliding through Kent as if Kent were laid out for your pleasure. There are no obstructions. The lanes flow onwards, river roads, like the threads of a wide, braided stream making its way from north-east Kent to the woods of the High Weald. One French landscape historian, describing the lanes and paths of the Limousin, called them ‘les lignes maîtresses du terroir’. It is a phrase I have always loved, the mistress lines of the country, and that is what these subtle, unnoticed and slippery lanes of the Low Weald are like. They govern what they cross and predate the places they join. They are the matrix to which everything else in the end submits. Sometimes the old lane has not been taken up by the modern tarmac network but continues as a footpath across the fields or as a track used only by a farmer, and then, on foot, away from any traffic, you can feel as close to the beginnings of this place as in any other experience of the landscape.

This can only be a suggestion – it is neither provable nor disprovable – but it seems to me that these routes into the Weald are the oldest things here. And it is perfectly likely that they are not a human construct. They may be older than the presence of people here, the fossilisation and defining of routes into the great half-open, half-grassland forest, used by the early herds. This making of paths by the great herds into the wilderness is a universal fact. When men came to lay the first railways through the Appalachians in the mid-nineteenth century, the routes they chose were the tracks that had been made and kept open through the Virginian forests by the trampling and grazing of the bison. Our Kentish lanes may have the same beginnings.

Sissinghurst in antiquity was not part of the solid, impenetrable and frighteningly dense forest, but threaded with these through-paths making their ways between the clearings and thickets, finding themselves sometimes in savannah-like parkland where the deer grazed and game was to be had, sometimes passing through patches where young oaks were sprouting up between the thorns and the hollies.

The deep past, then, was not, as we are so often encouraged to imagine it, some desperate and dreadful experience coloured only by threat and unkindness, but full of possibility, excitement and beauty in the empty half-open woodlands which were here then. Half-close your eyes one evening in Blackberry Lane and those four images from the Cranbrook bosses will come back to you: a relaxed beneficence among the fresh green hawthorns; some anxiety in the shadows; the bird half seen in the obscuring trees; and the big-mouthed grin of the goggle-eyed wood god. It is all here now and it was all here then.

There was one last object which if it had survived might have been the emblem of Sissinghurst two thousand years ago. It represents a little window on the distant past which opened in a Victorian summer and has since closed. George Neve, the distinguished tenant farmer here, a man of parts, contributor to the letter columns of national newspapers, was settled into the large and comfortable brick farmhouse at Sissinghurst which he had built almost twenty years before. The young cedars of Lebanon he had planted on his south lawn were eight years old and doing well. The laurels and rhododendrons in the dell next to his house were beginning to gloom over satisfactorily. It was time to show the county what sort of man he was.

George Neve invited the general meeting of the Kent Archaeological Society to spend part of its day at Sissinghurst. They came on 24 July 1873. Earl Amherst would be attending, as would Viscount Holmesdale, his son. There were about 140 people in all, including a general, an archdeacon and twenty-five vicars, many with their wives. After a preliminary meeting in the South Eastern Hotel in Staplehurst, they visited Staplehurst and Frittenden churches, and then came on to Sissinghurst in their carriages, where ‘Mr George Neve, of Sissinghurst Castle, most hospitably invited the whole company to partake of luncheon in a shaded nook upon his lawn, where tables were laid with abundant refreshments’.

After lunch, the company re-entered their carriages and went on to Cranbrook Church. Before they left, Neve would undoubtedly have shown them his treasure. It had been ploughed up five years before, at a depth of about eight inches, from a field near Bettenham, no more specific than that. A few years earlier, in another neighbouring field, the men on the farm had ploughed up an urn containing some bones. That, unfortunately, had been destroyed, but the treasure found in 1868 Neve had kept, and had even had photographed. An image of it would be reproduced in the volume of Archaeologia Cantiana that reported his lunch party. It was a gold ring, made of two gold wires, twisted together. One of the wires was thin and of the same diameter throughout; the other was three times as thick but tapered along its length to a point.

It was a piece of Celtic jewellery, belonging to someone about two thousand years ago who spoke a version of Welsh or Breton, the kind of ring that is found all over Europe, from Bohemia to the Hebrides. Its twistedness is the mark of a culture that liked complexity and the way in which things could turn inward and mix with their opposite. It was a beautiful thing: private not public, suggestive not assertive, symbolic not utilitarian. Perhaps it was a wedding ring, a binding of two lives, in gold because gold is everlasting. At some time in the last 130 years, this precious object has disappeared, but at least we have the image of it and the knowledge of its existence. I see in the Bettenham ring the culmination of this first phase of Sissinghurst’s existence. It – and the fact of a burial being made here – confirms a certain view of the ancient Wealden past. This was not, at least by the time of Christ, some godforsaken, Tolkienian forest in which trees loomed and rivers dripped, where people trod rarely and fearfully. Far from it: people knew Bettenham and Sissinghurst as theirs. Stream, meadow, wood and track, long summer grasses, spring flowers, the spread of archangel, stitchwort, campion and bluebells on the edge of the wood, the flickering of light down on to the water, the flash of the kingfisher, the pike in the dark pools, the songs of the nightingales and the woodpeckers, the swallows and house martins dipping on to the ponds, the fluster of pigeons, the flicker of kestrel and sparrowhawk: they would have known it all – and more, not in some marginalised way, scraping a desperate, squatter existence from the woods, but with comfort, gold, elegance and the symbolising of love and mutuality in a ring. They would have farmed here. Even two thousand years ago, Sissinghurst was home.