Renewal

The decision to go ahead with the farm project had been made in December 2007. It seemed for a time as if all was set. Advertisements were put in relevant papers for a project manager; for a vegetable grower and a deputy; and for a farmer. Early in 2008 we had a string of open days on which candidates came to Sissinghurst for their interviews and to be walked round in the cold and the wind. It was exciting. Here at last, living in flesh and blood, were some of the people who were going to make the change.

The first to join was the new project manager. Tom Lupton is a tall, big-voiced man, Oxford-educated, with a long history of land-management in the tropics, a hunger for order and eyebrows that jump at each emphasis in a sentence. It was like having the engineer on the Aswan dam supervise the building of your pond. Why was he doing it? Certainly not for the National Trust salary. More because it was ‘an ideal thing to get involved with. It was an idea with a very holistic view, doing things I have spent all my life doing, using land to improve people’s lives at the same time as protecting the environment, and done by an organisation which takes a long-term view. It was a marriage of all those things.’

Next was the vegetable grower. The ad in Horticulture Week came out in February 2008. Amy Covey, a twenty-three-year-old, with a big-teeth smile and a blonde, tanned presence as buoyant and English as her name, was working in a private garden in the Midlands. She was young to take it on, but we all felt when she came for an interview and we showed her the bleak unploughed, wind-exposed stretch of ground that was going to be her vegetable garden that her sense of enthusiasm and capability, her wonderful undauntedness, was just what Sissinghurst needed.

Third in this flow of new blood was to be the new farmer. But here it went wrong. A farming couple was chosen but after months of negotiation with the Trust, no agreement on the details of the tenancy could be reached and they withdrew. It was the first sign that the sailing might not be all entirely plain.

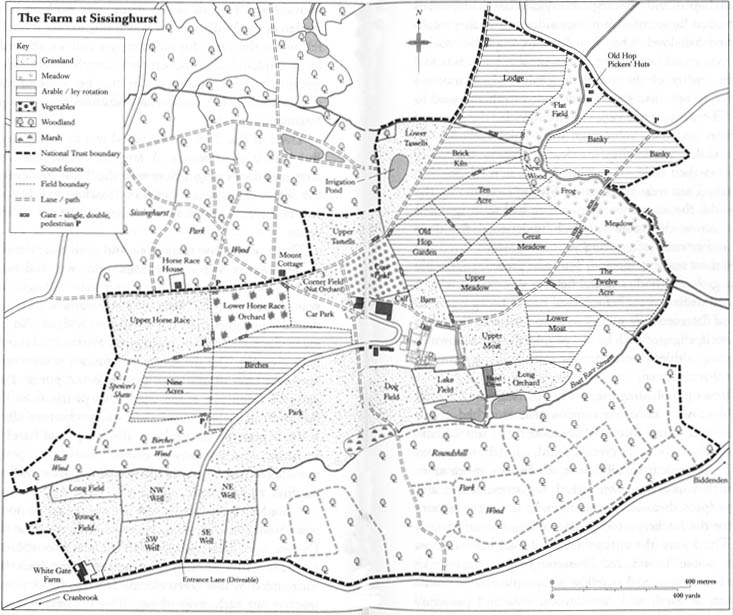

There were some marvellous and optimistic developments. A three-and-a-half-acre vegetable plot was laid out in nine different segments, the crops to rotate through it year by year. Peter Dear, the National Trust warden, had it manured, drained, ploughed, fenced, gated and hedged. An extra segment was added for the children of Frittenden school to grow their own veg. The site for the polytunnels was set up behind a screening layer of oak trees. Irrigation was put in. Peter and a party of volunteers made windbreak panels from the wood, using chestnut poles and sliver-thick chestnut slices which he wove between the uprights. Birch tops and hazels were cut for the peas and beans to climb. Peter drew up a plan for the whole farm in which all the hedges, gates and stiles were carefully and exactly detailed.

I loved it all. Suddenly, new life was springing up out of the inert Sissinghurst ground. It was slightly rough at the edges. Despite some ferreting earlier in the year, the rabbits wrought mayhem with the early plantings and the beds had to be surrounded by low green electric fencing. Black plastic mulch marked out each strip of veg. The soil was not as good as we all had hoped and the vegetable gardeners had pushed grapefruit-sized lumps of clay to one side so that they could get each bed half-level. The sown lines were a little wobbly and there was an ad hoc feeling to the garden, but it was this hand-made quality of the vegetable garden which touched me. Not for decades had someone attended to this ground in this way. The paths worn between the rows by the boots of the gardeners and their volunteers; the picnic tables for the Frittenden children; and the Handbook of Organic Gardening left on the tea-shed table: all were marks of a new relationship to this place. They were the signs of Sissinghurst joining the modern world, the same movement which had re-invigorated allotments across the country, which understood the deep pleasures and rewards of growing your own, which loved the local in the most real way it could. This new presence of people out on the ground – bodies in the fields – was exactly what I had dreamed of four years before: land not as background, as wallpaper or flattened ‘tranquillity zone’ to walk your dogs, but the thing itself, engaged with by real people, the plants sown in it bursting into a third dimension, the soil the living source of everything that mattered.

Sarah drew up a planting list of what the veg garden could and should grow, a cornucopia menu that stretched across the months and years. Intensely productive but not labour-intensive salads, herbs, leafy greens, chard, spinach, courgettes and beans. Alongside them all the veg which taste much more delicious if they have just been picked: tomatoes, carrots and sugar snaps (peas themselves were thought to be too labour-intensive for the kitchen – too much shelling for not enough product). Third were ‘the unbuyables’ – unusual herbs such as lovage, the edible flowers, red Brussels sprouts, stripy pink-and-white beetroot, as well as yellow and purple French beans. All of them, as Sarah said, ‘for flavour, style and panache’. Kales, leeks and purple sprouting broccoli, ‘the hungry gap crops’, would grow through the winter and be harvested in March and April when the restaurant opened for the season. Raspberries, blackberries, gooseberries and red and black currants were planted in long lines between the nine sections of the garden, both to provide windbreaks and to give the plot a visual structure. Forty new volunteers were recruited to help work there and in the polytunnels.

Tom, Peter and Amy drew up plans for the new orchard. A third of it was to be filled with 90 big old-fashioned apple trees (mainly juicing varieties so that the apples could be collected from the ground and no one would have to climb high in the trees to pick them). Most of the rest, just over three acres, was to be smaller modern trees, 1,500 of them, no more than eight feet tall, for easy picking and tons of fruit. Plums, apples, pears and a few cherries: a vision of blossom and fruiting heaven. I had the idea of putting thirty acres of hay meadow back into Frogmead along the banks of the Hammer Brook and meadow experts came to advise. Peter was designing wet patches for birds and dragonflies along the streams and a new rough wood to extend the habitat for nightingales and warblers. We bought some new disease-resistant elms to place around the landscape as the great towering tree-presences of the future. Architects redesigned the farmhouse as a modern B&B.

Everywhere you looked, all through the spring and summer of 2008, change was underway. More people, new people, new structures, new land uses, new relationships. All these changes were exciting but it also felt like a long, slow earthquake heaving up under a stable and intricately defined place. Inevitably, the stress and grief began to tell. Difficulties, tensions and rows started to break out. There were tears and snubbings, huffs and confrontations. No one had quite understood how deeply these ideas for the place, and all its emphasis on reinvigoration and the re-animation of the landscape, would disturb the people who lived and worked here.

People were getting angry, offended, offensive and dismissive. I talked to Tom Lupton about what was going wrong. He is the definition of a wise dog and one of the problems, he said, was that I had not properly understood how deeply attached other people were to Sissinghurst. I had assumed I was the only person to whom it meant a great deal.

There is a lot of emotion tied up in this project. From you, of course. You have obviously staked a lot in it. But that’s true of a lot of people who live and work here. Sissinghurst is not like going into the supermarket. People come here and very quickly form emotional bonds. They love it. It feeds many individual needs, which are very difficult to get fed in many places these days. Sissinghurst spoon-feeds it to people. As you walk from the car park, you are given these wonderful, sensuous experiences. In through the gateway, the tower, you wander into the garden. It’s beautiful but it’s obviously been beautiful for a long time. That is very reassuring and very comforting. It’s a refuge but it does a bit more than that. I can’t believe that many people don’t leave here feeling better. It’s a recharging point and for people who work here it has an increasing value to them the more they are steeped in it. You, Adam, need to be aware how many other people have loved being here.

It was well said and I heard it clearly. I asked Sam Butler, the National Trust Visitor Services Manager, about this too. Why were people so attached to Sissinghurst? Was it just a tranquillity balm? I had always thought of it as a place that should have life and vitality, which should feel enriched by the things going on here, by a sense of a living landscape not an embalmed one. Sam gave me a sceptical look.

I know you would like to bring the farm up close around the garden so that there was more of a contrast. I can see that, but I quite like the feminine, soft, National Trust sanitisation. I quite like that because that is where I am comfortable but what you are proposing is much more masculine and that’s unknown territory. I am not sure how I am going to respond to that.

Really? Was a sanitised, blanded-out soft zone really what was needed?

I like it and most of our visitors like it. It makes it accessible and for those who don’t know the countryside, they need their hands holding, giving them a comfort zone so that they can access it without it being too threatening.

How was she feeling about the whole transformation? A week or two before, at a meeting, she had suddenly coloured up at something I said.

It was like a slap in the face. I had been listening to you and Tom and I suddenly realised that this place was going to change for ever in the way I felt about it. It didn’t matter whether it was good or bad. I knew it was different and that for me was a loss, because I have been tied to this place for such a long time.

We have visitors who come here every Saturday morning to read their papers in the orchard, who used to come here maybe with a partner or a husband or a wife or a child they have lost and they now come here to reflect as well as to enjoy the flowers and the views and the vistas. And you know we must look after those people too.

All this was an education for me, almost the first time I had ever listened to the stories other people at Sissinghurst were telling me.

The real pinchpoint, though, was the restaurant. It was vital that the restaurant changed to reflect what was happening in the wider landscape. It would make little sense to set up all these connections between land, place and people if the restaurant continued to produce food much as before. Sarah, who was the author of prize-winning gardening and cookery books and had a decade’s experience of growing and cooking vegetables for her gardening school in Sussex, if no knowledge of running a large-scale catering operation, took on the task of introducing the restaurant to these new hyper-local sources of produce. She tried to persuade the managers and chefs to adopt a new responsiveness to the food coming in off the field. For months, over these questions, there was an agonised non-meeting of minds.

Both sides felt deeply unappreciated by the other. Ginny Coombes, the restaurant manager, who has been generating quantities of cash for Sissinghurst year after year, felt bruised by the whole process.

There is no appreciation of how far we have come, or of what we have taken on. A lot of ideas have been thrown at us and it isn’t easy. We are moving in the right direction and we are doing a lot already with local and seasonal. That’s my mantra! It is something the Trust has been working towards for years. And we are improving year on year. Someone needs to say, ‘Listen to the staff, they run it, they know what they are doing. We want to help you improve what you have got already.’ But we don’t feel that anyone is saying that.

It was never going to be easy. For chefs and restaurant managers used to high-pressure, high-volume production of meals for hundreds of visitors, often in less than perfect circumstances, all our talk of ‘the dignity of vegetables’ was not even funny. Mutual frustrations erupted. Sarah pursued her gospel: vegetables are cheaper to grow than meat, better for the environment, better for you, utterly delicious when they are so fresh, and make you feel good when you know exactly where they have come from. And Ginny said ‘Look, do you know what it is like in here on a busy day?’

When you came to me three years ago and said ‘What about growing our own veg here?’, I thought that would be a wonderful thing. But it has all got so over-complicated. I love what Sarah does at Perch Hill and I listened. That is all fine when you have fifty people to feed. When you have got a thousand people a day, they want choice.

Early in June 2008, to get some understanding of what Ginny and her staff were having to deal with, Sarah and I worked in the restaurant for two days, her in the kitchen, me on the tables, behind the counter and doing the washing up.

Seeing it all from the other side was pure reality-check. The customer demand was relentless and the need to shave costs unbending. The building – a restaurant inserted into an old granary-cum-cow-shed – is badly laid out. For the staff it is often unbearably hot as wafts of hot air come from the industrial dishwasher, the heated counters or the ovens. The clearing away system does not help the waiters and there is a lot of double handling. The queue for a pot of coffee gets muddled with the queue for the hot dishes. Space behind the counter is cramped and, where different routes cross, inconvenient. Everybody works unrelentingly hard and remains cheerfully nice to each other through the heat and harassing customers. And everybody ends the day exhausted. I felt I had been in a trawler for eight hours. Only when one of the visitors said ‘This must be such a nice place to work,’ did I very nearly ask him if he had just landed from Mars.

Of course this restaurant finds it difficult to embrace any change. An irregular supply of vegetables from the plot, in variable volumes, is going to need an elastic frame of mind. Working in this tight and difficult environment allows no room for elasticity. I asked Ginny about this. ‘People here don’t see our side of it, our passion for it, the work and energy we put in here,’ she said.

I know you saw it the other day, how drained people are at the end of a working day. But nobody gives us credit for it. And nobody knows exactly what is needed. It is all big ideas, everybody thinks they know better than us. We are taking on board the advice that everyone seems to be giving us, but give us time.

It was in truth a culture clash between Sarah and the NT restaurant staff. There was an assumption on their side that Sarah was promoting her own private agenda, when she felt she was ushering in part of the food culture which had been the lingua franca of food writing, restaurants and shops on both sides of the Atlantic for the last twenty years. An emotional and resolute refusal to entertain most of her ideas made her feel as if she was banging her head against a wall. Parts of the National Trust wanted her to contribute, others didn’t. ‘All I am trying to do is modernise the restaurant in its attitude to fresh produce, to simplicity as the modern way. They think I am trying to extend my empire. And the organisation can’t back me up because they have to support their staff. But you don’t have to wave goodbye to flowers and texture and freshness and goodness just because you are providing two hundred meals a day.’

Late that summer, Sarah and I went to a meeting in London with Sue Wilkinson, the NT’s director of marketing. She told us, in effect, that the place Sarah was trying to take the restaurant was not the place the NT wanted to go. The local food managers had said that ‘the expectation of the general public was the “hot two-course meal”’ and the chef at Sissinghurst had reiterated that: ‘This is a standard fish and meat and three vegetables place. It always has been and always will be.’ Sarah had arranged for Peter Weeden, head chef at the Paternoster Chophouse, a London restaurant which specialises in modern, fresh, seasonal food, to be brought in as a consultant but his contributions were rejected. ‘Maybe Sissinghurst is not ready for that much change,’ he said when he left. When Sissinghurst volunteers were asked about suggested changes to the restaurant menus, one said, ‘Just because Vita went to Persia and ate some curry or whatever they eat there, I don’t think people would really want that experience here.’ And another: ‘I don’t think you come to Sissinghurst wanting Chinese meals. I’m sure that’s not people’s expectations.’ A man I had never met said to me at the garden gate, ‘It all depends on whether people prefer olive oil and vinaigrette to bangers and mash. And if it’s bangers and mash, you’re going to have egg all over your face, aren’t you, Mr Nicolson?’ I said I didn’t think he had quite understood the whole picture.

Much of what Sarah was suggesting – a freer, looser, richer, more internationalist line – was not only part of the modern mainstream but came from the roots of modern Sissinghurst. That cut no ice. An almost purely conservative sense of ‘we know best’ carried the day. In the autumn of 2008, Sarah took a step back. The Food Group at which she had tried to persuade and show the National Trust catering staff what she had in mind was disbanded. It was agreed that she should provide the restaurant with the recipe for a single dish a month, which they would trial. Her relations with the restaurant manager and chef should from now on be exclusively through the National Trust hierarchy.

At the same time, I was also suffering my defeats. I had been asked by the property manager to devise a new, historically based approach for the area immediately outside the garden, between the car park, the ticket office and the front gate. Over the previous thirty years, it had been managed in a bland, corporate, golf-course style of large swathes of mown grass with ornamental trees. This was the first part of Sissinghurst to be seen by visitors and to my mind it gave all the wrong signals. I wanted it to be more rural, to give a sense that this was a garden in a farm, that Kent itself not suburbia lapped at the garden walls. But the head gardener did not see the point, or at least did not agree with it, and told me that she and the property manager alone should decide how it was managed. The grass would be allowed to grow a little longer around the edges but essentially the area should remain unchanged. The Trust hierarchy supported her and the ideas I had been asked to provide were dropped.

By the autumn of 2008, things were looking glum: no farmer; little change in the restaurant; no change in the immediate surroundings of the garden. Then it got worse: although the veg garden was going organic, the conversion of the farm to an organic system was delayed three years; the tenancies of the bed & breakfast and of the farm were separated, as it was thought unlikely that a single couple would be able to do both. As the farm was so small, this meant that the farm would not have a dedicated farmer of its own but would again become part of a larger enterprise. I felt that the idea I had originally proposed was suffering death by a thousand cuts, that the all-important connections between farm, food, restaurant, bed & breakfast, garden, history, land and people were all being neatly snipped one by one. And if the connections were cut, where was the idea? In her poem about Sissinghurst, Vita had written that here, at last, she had found ‘in chain/The castle, and the pasture, and the rose.’ That chain, the vitality of connectedness, was what now seemed to be in danger.

Fiona Reynolds, the director-general and chief executive of the Trust came down to see me and told me that I needed to look at things more optimistically, that it was damaging to morale only to look on the downside and that I was ‘an old Romantic’. After she left, I thought about that phrase and realised that what, from the outside, looked like Romanticism seemed to me like a belief that only something done wholly was valuable. People don’t come to Sissinghurst because it is quite like everywhere else, shaped by the tastes and expectations of everywhere else, but because it is exceptionally itself. Its potential for beauty and richness needs to be entirely understood and made entirely explicit, not buried under a duvet of the average. It needs to embody a completely fulfilled relationship of all its parts. That should be the aim and goal of what was done here now. It might be the motto for this entire project. Nor is that goal merely Romantic in the derogatory sense. As a result of the publicity surrounding the publication of this book in England in the autumn of 2008, an extra 15,000 visitors came to Sissinghurst in those months, spending an average of £10 each. They were drawn by the idea that something courageously different from the norm was being done here. At the beginning of the beautiful and sunny 2009 season, visitor numbers at all National Trust properties were up on average 30 per cent. Sissinghurst, largely as a result of a BBC television series about the project, filmed over the course of 2008 and broadcast in February and March 2009, was up almost 70 per cent. If nothing else, Romanticism is good box office. Vita and Harold saw that. And the wholly done thing, driven to fulfil itself by a powerful and commanding sense of its own value, will always be at the root of the beautiful landscape, the beautiful painting or the beautiful piece of music. Beauty is not based on consensus. Beauty would be impossible without exceptionalism, a denial of the average. It stands out for its own idea of itself. That is not the only ingredient, but it is certainly a necessary part of it.

After Fiona had left, and under her prompting, I made a list of what was good here. There was a lot. The new orchard had been laid out and marked with chestnut stakes from the wood. 636 young fruit trees (cookers, early eaters and cider apples, greengages and Victoria plums, three different sorts of cherry, with a range of fruiting season, and delicious Doyenne du Comice pears, as well as Concorde and Conference pears for cooking) were planted as soon as the weather allowed. Almost a mile of new hedges on the old lines were marked out across the big arable fields, and as soon as the ground dried, the new ditches alongside them were dug and thousands of hedge-plants planted. New water troughs, piped water and new fencing were all put into the permanent pasture. Thirty-five acres of a new streamside hay meadow (on Frogmead, probably a meadow for about a thousand years before it became a hop garden in the 1860s), two new pieces of scrubby woodland, ideal for nightingales and willow-warblers, and a new ‘scrape’, a slightly dished boggy patch by a stream, were designed as a dragonfly- and wader-heaven. On 1 January 2009 the vegetable garden had gone into organic conversion, under the auspices of the Soil Association. New advertisements for the farmer and the B&B, although separate, would at least refer to each other, so that a chance remained that farm and farmhouse would be reconnected. There was a presumption that in 2012/13 the farm would go into organic conversion.

This was the inventory of where, early in 2009, the project stood in relation to its original intentions.

OUTCOME 2009 | |

Meadows |

Yes, bigger than envisaged |

Orchards |

Yes and more planned |

Nut orchard |

Yes, if small |

Beef Cattle |

Yes |

Sheep |

Yes |

Vegetable garden |

Yes, a great success |

Volunteers on the land |

Yes |

Smaller fields |

Yes and others planned |

New woods |

Yes |

New wetlands |

Yes |

New hedges on old lines |

Yes and others planned |

Farm supply to restaurant |

Yes from veg garden, planned from farm |

Restaurant to reflect farm |

Yes, partly, but a way to go |

Pigs |

A good possibility |

Chickens |

A good possibility |

Organic system |

Planned, but some hesitations in the air |

Farmer as resident |

A possibility |

B&B as integrated part of farm |

A possibility |

Dairy Cattle |

No (but a micro-dairy remained possible) |

Hop garden |

No |

Redesign of garden surroundings |

Not in detail but the atmosphere is changed |

‘A place exceptionally itself’ |

Coming on … |

It was a mixed picture, but the feeling here that spring was one of enormous optimism, that the landscape around Sissinghurst was one of possibility. There had not been a snap change, nor should there have been, but something was under way which five years later had the chance of being as deeply and integratedly wonderful as any Romantic could wish. An old friend of my father’s, who had known this place all his life, wrote to me after he had seen what was beginning here, and said, ‘It’s as if we have all been blind for the last forty years.’ Scales were falling from eyes.

One important question remains unaddressed: does this project have any significance beyond itself? Partly, my answer is No. These ideas are about this place, this ecology, human and natural, this particular set of connections between people and place. And that particularity is its virtue.

But the question recurs. Is it not just a private indulgence, an exercise in the unreal, attempting to impose on the real world ideas which belong in a dream or on stage? Is it a masque, a replaying of ‘The Shepherd’s Paradise’? Or an attempt to ‘turn the clock back’, as people have often said, a nostalgic and unreal longing for something that no longer exists?

I passionately believe that it is none of those things, and I will make my case here, but these are questions and criticisms that need answering. Three people have put versions of them to me recently, two in public, the other in private.

First, the journalist Simon Jenkins, now chairman of the National Trust, produced a hybrid objection. On the platform of a meeting we shared in Oxford he said (in a perfectly friendly way) that in promoting these ideas, I was ‘acting out a combination of an eighteenth-century squire and a hippy’. The motives behind this project were both doolally idealist and deeply pre-bourgeois and pre-industrial conservative. ‘Adam has an agrarian vision, wants to return Sissinghurst to the conditions of his childhood in the 1960s. Why should the National Trust do that? Other people, who work there, are just as attached to the highly successful Sissinghurst of the 1980s or 1990s. Why should Adam’s vision of a dream world have priority over any other? Why is his childhood important?’

The second public objection took one of these elements – the squire line – and played it harder. Charles Moore, a prominent right-wing columnist, neo-liberal and Thatcherite, who was at school and university with me and has been my friend for forty years, saw the Sissinghurst project as little but snob drama. He had watched the beginning of the TV series and reviewed the first programme. ‘It’s the lower middle classes who own England,’ he wrote in the Daily Telegraph, but Sarah and I, apparently, did not like them. Instead, we had a vision of a world which we controlled.

What emerges at once is that the staff at Sissinghurst do not like what Adam and Sarah want. The chef thinks her idea of lots of home-grown vegetables and less meat might be fine for London, where people like being ‘conned’, but will never do here.

The head-gardener is told by Sarah that she has just destroyed a romantic little corner of the garden in her desire to make everything ‘too perfect’. Perfection, she says through gritted teeth, is exactly what she is trained to provide.

It does not take long to see that the clash is irreconcilable. What she and Adam cannot say – but clearly feel – is that the Sissinghurst restaurant is frightfully common. Even when redone, the floor is too shiny, and there is too much vinegar in the beetroot. The staff use words like ‘condiments’, which make the Nicolsons wince.

The stalwart staff at Sissinghurst hate mess, worry about how to run the place efficiently, and feel unappreciated by the couple. Related to the question of class is one of ownership. To whom does Sissinghurst belong? In law, of course, it belongs to the National Trust. It is a hopeless, soul-destroying quest to try to own what you cannot, and one feels enormous sympathy with the poor, despised Sissinghurst workers. Why should they have all this emotional and dynastic baggage dumped on them? This series illustrates the great argument about who owns England. The answer is, the lower middle classes, the people Kipling called ‘the sons of Martha’. One’s romantic streak may regret this but, in the modern world, our life, liberty and property depend on it.

The first effect of this article was to irritate everyone who works at Sissinghurst. Lower middle class? Who was Charles Moore? And who was he calling the ‘sons of Martha’? Who did he think he was? I was blackened by association, for being his friend. But what could I say in response? There was no way I was dumping emotional or dynastic baggage on anyone. I had been to hundreds of meetings to avoid any dumping. I didn’t want to become any kind of squire here. I had always recognised that none of us would be living here without the National Trust. We lived in an extraordinarily privileged situation. My motive was not any form of control but of partnership. I did not feel that I had any rights over the direction of things at Sissinghurst because of my genes. The only possible justification for raising these ideas was that I had known this place a long time, had thought a great deal about it and the relationships that lay at the root of it and had researched its story carefully. Future directions would benefit from deep roots. Of course we did not despise the people who worked here, nor was I trying to own what I could not. Charles Moore labelled Sarah and me as nostalgic snobs but I cannot think of a single thing we have done which could justify that.

Simon Jenkins had said hippy-squire; Charles Moore had said squire; Oliver Walston said hippy. He is a barley-baron, owns a 2,000-acre intensive arable farm in Cambridgeshire, entirely dependent on chemical fertilisers and pesticides, feeding wheat and oil seed rape into the international commodity markets, and over several decades has been steadily subsidised by the European Union to the tune of some £200,000 a year. When he was a boy eighty people worked on his land. Now he has two employees who drive the giant tractors and the very large Klaas combine harvester (which drinks £700-worth of diesel a day). His job of managing them and the farm, he says, takes up 15 per cent of his time. Much of the rest of it he spends in his charming house in Fleurie, in the Beaujolais, writing brilliant, candid articles for the press which are designed to inflame environmentalists.

In April 2009, I asked him to come to Sissinghurst to look at what we were doing. I also asked Patrick Holden. He is both an organic dairy and carrot farmer in the far west of Wales and Director of the Soil Association, Britain’s leading organic organisation. I asked them both how this tiny farm project stood in relation to the world.

On one thing they were agreed: in global terms, a crisis was approaching. For Patrick, it was

the biggest crisis there has ever been. We are the binge generation. Agriculture has been spending beyond its means for more than a hundred years, treating environmental capital as if it were income. Fossil fuels, minerals, phosphates, water, soil fertility, human skills capital – all that collective capital, much of it laid down by centuries of relatively sustainable farming, has been used up in the last hundred years. We now have an industrial agricultural system which crudely uses ten calories of fossil fuel energy to grow one calorie of food. That is not sustainable and it will only go on as long as there is any environmental capital to exploit. The problem we face is that we have nearly used up the store. And we have exponential world population growth and climate change which is going to shrink the area in which agriculture is possible. The crisis will come in fifteen years if we are lucky. We cannot go on as we have been.

Oliver Walston’s answer was to quote Earl Butz, the 1970s apostle of industrialised farming: ‘Before we go back to organic agriculture, somebody is going to have to decide what 50 million people we are going to let starve.’ Every acre of Walston’s farm grows 16 tonnes of wheat every decade. No organic farmer could approach a third of that yield. That is the wheat problem. If there are going to be 9.5 billion people in the world in 2050, they will need wheat to be grown by efficient, Walston-style chemical and industrial methods. Any other form of farming can be no more than a niche, to satisfy rich, middle-class customers who are keen on wildlife. ‘I am interested in sustaining human beings,’ Oliver said. ‘Patrick is interested in sustaining an agricultural system.’

He admitted, though, that his type of farming was not sustainable. Finite reserves of phosphate, potash and fuel mean that it cannot continue into the future. His answer is what greens call ‘a techno-fix’. Science has come up with solutions in the past. There is no reason to doubt it will again.

For Patrick, the nub of the crisis is in the relationship of energy and fertility. The coming shortages of fossil fuel will need us ‘to switch from the energy capital laid down over the last 150 million years to operating within current solar energy input. And the biggest single change is the switch to generating fertility from solar energy within the farming system. Of course we will need tractors and there will be techno-fixes to fuel them. But we won’t be able to power the growing itself by artificial fertiliser because natural gas is going to run out and the amount of energy required to fix a tonne of nitrogen fertiliser is enormous.’

He described a revolution in the farmed landscape of Britain and the rest of the industrialised world. Cereal production will halve. And as half of all the grain grown in the industrialised world is fed to animals in sheds, most of that form of agriculture will also disappear. It will be the end of intensive poultry and pigs. Dairy cows will return to what they were before the 1960s, not relying on grain but eating grass, ‘dual purpose’ – i.e. dairy calves will make good beef animals. Human diet will have to change. There will be less white meat, although this is not a vegetarian system. In a sustainably farmed Britain, half the land area will be in clover or grass or permanent pasture and the best way to harvest that phase of the rotation is with cattle and sheep. There will be a great deal of red meat, milk and cheese, as well as grass-fed poultry and pigs fed on swill and grass. ‘This is not a question of choice,’ Patrick said. ‘We have got no choice.’

Oliver Walston’s hopes were pinned on a new kind of genetically modified wheat, which has genes from a nitrogen-fixing bean implanted in it so that, as the wheat plant grows, it derives its own nitrogen fertiliser from the air. No need for any artificial fertiliser, no need for any break-crops. It could be GM nitro-wheat year after year, feeding the world.

The question for me was how to connect this giant global agenda to any of the intuitive desires and ideals I had for Sissinghurst. Was there no way in which the plans for Sissinghurst could be seen as more than a first-world luxury, the twenty-first-century Petit Trianon? Was everything I believed about it finally trivial, a form of exterior décor? What about local meaning, I asked them, the particularity of doing particular things in particular places? Did that have no role in their thinking?

Patrick of course thought it did. ‘The old idea was if you wanted to solve the world’s food problems, get a bunch of global leaders together, they will hatch a plan, the G20, trillions of whatever, they will do it top-down and things will be all right. But the really interesting thing is what the bottom-up components of that top-down plan will be. I am thinking about that, driven by selfish motives because unless I make the necessary preparations on my own farm in Wales, when the crunch comes, the food crunch, I am scared that my business will collapse.’

Oliver answered in terms of the market. ‘If I were running Sissinghurst now, I would be growing organic food for the restaurant. The punters can afford it, they will appreciate it and so you should go for it. If I opened a restaurant in Grosvenor Square, I would do the same. If I opened a restaurant in the poorest parts of northern England, I am not sure I would.’

Oliver talked about the changes he had seen since the 1950s, the disappearance of so many farming jobs, the loss of wildlife on his farm, the way in which a farmer would have nothing to do unless he became a tractor driver. Those were real losses, but in no way did he look back to lost halcyon days. They weren’t.

Manual labour was the norm, lifting heavy sacks resulted in frequent back injuries and working in dusty conditions damaged the lungs. Wages were insulting, hours were long and holidays short. And above all the farm workers invariably lived in tied cottages from which, in theory at least, they could be evicted at the whim of the farmer.

And for Patrick, finally, the real loss, the loss that had to be made up, was in human and cultural value.

We have deskilled in one generation, lost people who want to work in agriculture. The average age in farming is nearly sixty. Most people think a job in farming is absolutely not cool, with low social, economic and cultural status. But here is something: all my children have got jobs in food or farming. And before that, they have all tried and left London jobs. And that pattern of re-connection, of re-acquiring the cultural, emotional and social skills that come with the growing life, that is what this huge challenge is all about.

So either (the gospel according to Patrick): we have to make the change, we ought to make it and we would like it if we did make it. Sissinghurst is a beacon, somewhere that can signal the virtues of those changes widely in the world.

Or (according to Oliver): we must not make the change, we cannot afford to make it, we must trust that a techno-solution will emerge, and we must accept the cultural and environmental losses which industrial farming imposes as part of necessity itself. Sissinghurst is an irrelevance.

Or maybe there is a third position: we need both. The two attitudes to land and food will continue in tension, mutually evolving, far into the future. Sissinghurst is not the answer to the world food crisis but it is an attempt to redeem some of the losses that have occurred over the last fifty years. It is an answer for itself and in that particularity lies its general significance.

Oliver Walston’s trajectory in East Anglia from 80 farm workers in the 1950s to 2.15 now (including himself) is symptomatic. Ten million European farmers have left the land since the 1950s. Even Sissinghurst’s neighbour farm, Brissenden, which in 2009 was made up of 1,000 arable acres farmed by Robert Lewis with the help of a single employee, had in the recent past been part of fourteen different farms (Bettenham, Brissenden, Catherine Wheel, Church Farm, Beale Farm, Commenden, Hammer Mill Farm, East Ongley, West Ongley, Park Farm in Biddenden, Whitsunden, Buckhurst, Ponds Farm and Street Farm). Nearly all those farmsteads are medieval, some go back to the Dark Ages. None of them now, except Brissenden, is connected to the land. A world that was almost continuous for 1,500 years disappeared in the 1970s and ’80s. The fate of Sissinghurst, described in these pages, was common.

Robert Lewis told me something of the Brissenden story. He is a strong, bluff man, although a little shy, with a way of looking at you from a distance, not a seeker of the limelight, but direct, without side, happy to plough his own furrow and to work hard for the goals he identified long ago: a planned approach, a systematic outcome, efficiency, self-reliance. ‘I have always got on with things quietly. It has served me better.’ He came to Brissenden from Essex in 1974, as farm manager for the landowners, Thomas and Marjorie James. Professor James was a lawyer at King’s College London and Marjorie had been a botanist at Kew. They had in mind, from the 1960s onwards, to make a landholding in Kent which would be viable in the modern world.

Gradually, from the ’60s through to the ’80s, the Jameses expanded their farm, always folding the profit into new acquisitions. It had begun with Bettenham and Brissenden, the two farms my father sold them in 1963. When Robert arrived, it was still a bundle of small, ill-drained fields, nothing but ‘cow pats and water grass,’ he says, ‘derelict dairy farms which we were welding together to make a single unit.’ It was a challenge he relished. He was twenty-seven then, away from his own county, surrounded by farming neighbours who were ‘difficult’ with him. ‘Some were better than others. But the point is we were doing something and most of them were sitting on their hands. There was a fair bit of jealousy.’ Perhaps they were waiting for the whole enterprise ‘to go tits up’, as stock farmers say. But it didn’t and Robert rationalised the stretch of country that increasingly fell into his hands. He took out hedges, made some enormous fields, one of them nearly half a mile long, put in drainage, demolished and moved many buildings, laid a lot of concrete, got rid of any animals in what had been almost entirely cattle and meadow country, and started turning in rich and rewarding yields of wheat, barley, oats, rape and beans. In those corners too wet to drain, with grants and advice from the nature authorities, he planted thousands of trees, plantations in which his beloved nightingales, mistle thrushes, nuthatches, wrens and woodpeckers, tree creepers and grey wagtails all now gather.

‘The locals complained a lot,’ he says, ‘but it has been an unqualified success. The farm is in better heart than when it was found.’ It had been heavily infested with black grass and wild oats. That has been largely dealt with. Over 100 acres is now in an environmental scheme of one kind or another. ‘It is all you could do with it. The soil is silty, better than the sand up at Sissinghurst, but you couldn’t begin to farm it organically. It is not easy ground. It is not even girls’ ground. Everybody says they have the worst land in England, but this is hungry, low in potash and phosphate. You would be very pushed to do anything different here.’

The modern Brissenden is a monument to the age in which it was created. There is of course no doubting the good intentions of Robert Lewis or the Jameses. They were pursuing a goal of ‘improvement’ when confronted with a place that looked as if it had failed. And it is heavily locked into patterns of world distribution. Robert told me how the soft wheat he now grows here gets trucked in lorries to the big container port at Tilbury, pumped into the holds of giant bulk carriers and shipped to Dubai and other parts further east to make chapatis. No sense of local provenance, nor of local habits has survived the great transformation. The landscape of his vast fields is, despite the green corners and edges, fiercely denuded. He farms with extreme care, there is almost no sign of herbicide spray drifting beyond the farmed area. The whole place is neat beyond belief. In the springtime, there are plenty of wildflowers, buttons of primroses, cuckoo-pint and wood anemones on the farm. But the vast fields might be anywhere. No sense of the past has survived the rationalisation. Any idea of it being a place with a history and memories has been suppressed. Its past is no longer legible and the form of the land does not speak. When walking on one of the footpaths that still crisscross it (and which Robert meticulously clears and signposts) I only want to leave, to find myself in the country I know. From every yard you can read only distant markets, global supplies. No one is here. Nothing comes from here and nothing is destined for here. There is no cycle, only inputs and outputs. Compared with the meadows and hedges, the small fields and intimate landscapes, the cherry orchards and field ponds of those few Low Weald farms which have survived largely unchanged, this is lacking in almost everything except its productive capacity.

Why does the Brissenden approach seem wrong? In The Language Instinct, Steven Pinker, now a professor of psychology at Harvard, very carefully describes how language is rich in redundancy. We don’t need to say half the things we do. We consistently say a great deal more than need requires. The most obvious wastage, as Pinker points out, is in the vowels. We can leave vowels out of the picture and still make our meaning clear. Yxx mxy fxnd thxs sxrprxsxng, bxt yxx cxn rxxd thxs sxntxncx xnd xndxrstxnd xt, cxn’t yxx? Sntcs lk ths cld stll, n fct, b ndrstd, lthgh ths s rthr mr dffclt nd slghtl slwr thn th sntnc wth th xs whr th vwls shld b.

You can read it but it’s not English, and tht tght-lppd, clppd wy f tlkng sounds a little mad. It’s not human. The natural human manner is voluble, assertive, open-mouthed, vowelly and over-supplied with signals. That communicative generosity is a sign of humanity itself, a form of biophilia, the love of vitality itself. The ever-present but strictly unnecessary vowels are, it turns out, symptoms of a much more general phenomenon. We surround ourselves with a thick meaning blanket, a pelt of significance. We don’t spit sharp little pellets of pre-digested information at each other like sharp-beaked owls. We lounge together in the same meaning bath. Redundancy, an over supply of meaning, and a certain inefficiency, are the defining qualities of a humane life.

This is an intriguing idea. For something of human and cultural value to be communicated, something more than that has to be cultivated at the same time. The stripped-down meaning, the thing made efficient, the thing reduced to essentials, has lost something essential in the process. Fuzz is more accurate than core. There is no such thing as a core meaning and a précis always lies because meaning is spread throughout whatever appears contingent or nearly irrelevant. Imprecision is the first requirement of understanding. Clarity obscures the nature of what it hopes to clarify.

The landscape is also a language. If you don’t want change to involve loss of meaning, the key question is: what about the vowels? What about the soft, subtle, pervasive and evasive, apparently inessential things which make so much of what is important but which can’t be measured, or not easily? What about the darkness of the sky at night, the bendiness of the lanes, the nature and form of the hedges, the precise form of the latches with which the gates open and close, the ways in which the orchard trees are pruned, the habits and colours of the local cows, the hereness of any particular here?

There is a difference between Sssnghrst or even Sxssxnghxrst, locations whose meaning can be understood but which read like components of a formula or marks on a despatch docket, and Sissinghurst, a rounded being, which I have always thought of as entirely female, like a sister turned into a place, a fully syllabled, generous description of home.

If we only attend to the consonants, and reduce a place to its obvious functions, if we make the operation of a stretch of country financially and technologically efficient, if we make it singular and pointed, rather than multiple and rounded, a good environment – that is a good place in which to live – will have been damaged. You might even say that the more unimportant something seems, the more important it is. Redundancy is all. Compare a place you love with somewhere no one could possibly love, perhaps one of those stretches of mown grass on the outside of an intersection, a curved region which looked good on the road engineer’s plan but which in reality is a piece of curved vacuity. One seems like a place and the other no more than a place where a place should be. And the difference between them lies in a certain unnecessary complexity, a bobbled scurf of things, the trace of the past, the embedded quirk, the wrinkle in a face, the burble of a particular family’s or a particular person’s lack of clarity.

It is the distinction between a landscape and a place. Landscape is an idea but place is a sense. Landscape requires a prospect, a surveying eye, even a controlling and appropriating eye, place an embeddedness, a skin experience, a kind of fleshy, sense-rich thickness. The only way to enjoy summer in England, according to Horace Walpole, was ‘to have it framed and glazed in a comfortable room.’ That is the landscape view. Coleridge in 1802 saw the Cumbrian waterfall called Moss Force in full spate, churning though its

prison of rock, as if it turned the corners not from mechanic force, but with foreknowledge, like a fierce and skilful driver. Great masses of water, one after another, that in twilight one might have feelingly compared them to a vast crowd of huge white bears, rushing one over the other against the wind – their long white hair shattering abroad in the wind.

That is an understanding of place. A landscape is seen; a place is experienced and known. And so the key qualities of place may perhaps be complexity, multifariousness, hidden corners, both closeness and closedness. A place rather than a landscape allows the folding of individual energies and passions into its forms. It must in other words be full of the potential for change and development, for a sense that its potential might be fulfilled.

There are a thousand ways in which this idea of connectedness can make its presence felt in the real world. Take for example, as a barometer of intent, the place of the hedgehog, as a symbol of the sort of landscape this book is arguing for.

Nobody knows very much about the hedgehogs – how many there are, where they are, how many are needed for a viable population, how they cope with modern life, or, in a country teeming with foxes and badgers, their natural predators. But one thing now is certain: the hedgehogs of Britain are dying out at a rate of about a fifth of the population every four years. By 2025, they will be gone.

Does it matter? I think so. The hedgehog has always been the embodiment of something subtle and tender in the landscape. It is not a flamboyant creature, but quiet, nocturnal and discreet. They doze in long summer grass where strimmers chop them up. They get tangled up in tennis nets. The hedgehog smells something delicious left in the bottom of a cup, pushes its snout in to lick up the remains and then finds the cup stuck to its prickles.

They have been protected from hunting since 1981, but they are dying now in a less obvious way. The prospect of their loss seems dreadful, partly, I think, because the hedgehog should be seen as the symbol of a kind of world, or even of a certain frame of mind: self-absorbed, private, snuffling through the landscape, self-protective, neither very dynamic nor sharp but dignified and curiously important.

This discretion of the hedgehog is not just literary or sentimental: a kind of patient unobtrusiveness is its central characteristic. What the biologists call the hedgehog’s ‘generalism’, its lack of slick speciality, the way it noses for beetles, caterpillars, earwigs and worms, sometimes eating frogs, baby mice, eggs and chicks, its happy existence at the bottom of hedges and in people’s back gardens, its inability to cope with very large, chemically denuded arable fields – in other words its fondness for the private, the scruffy and the marginal – all make it a measure of the state of the landscape’s health as a whole.

This book is perhaps an argument and plea for the virtues of idiosyncrasy of which the hedgehog is the emblem. At its roots, idiosyncrasy means a ‘private–co-mixture’, a coming together of qualities which are characteristic of that thing alone and which are in that way the reservoirs of value.

Last night with some friends, I went out into the fields and we listened to a single nightingale in the scurfy wood, beginning its song again and again, each time a new variant on what had come before, as if nothing inherited or borrowed was worth considering. Every snatch of its song was unfinished, an experiment in gurgle-beauty. You wanted him to go on but he didn’t, always stopping when the song was half-made. We listened, standing in the warm wind, waiting for the next raid on inventiveness. Every part of that bird’s mind was restless, on and on, never settling on a known formula, an unending, self-renewing addiction to the new, to another way of doing it, and then another, all in the service of a listening mate and the survival of genes. That is the nightingale’s irony: his brilliantly variable song is indistinguishable from his father’s or his son’s. Invention is nothing but the badge of his race. It is as if new and old in him were indistinguishable. That is the nightingale lesson: inventing the new is his form of repeating the past.

Is that the model here? Is that how we should do it too? I have been making some radio programmes about Homer and his landscapes. Reading the Odyssey now, at the end of this Sissinghurst story, brings something home to me. People think of it as the great poem of adventure and mystery, of a man travelling to strange worlds beyond the horizon, of the threat and challenge of the sea. That is true but it is only half of it. The second part, as long as the other, is devoted to something else: Odysseus’s home-coming to Ithaca and his ferocious desire, in the middle of his life, after twenty years away, to reform the place he finds, to steer it back on to a path it abandoned many years before. Homer certainly knew about homecoming. Odysseus thinks that all he need do is re-create the order he remembers from his youth, to cleanse the place of everything wrong that has grown up in the meantime and re-establish a kind of purity and simplicity over which he can preside. I hear the echoes of what I have done. ‘Nowhere is sweeter’, Homer says, as Odysseus bends to kiss the green turf of Ithaca, ‘than a man’s own country.’ That is what we might like to think, but the truth is harder. Nowhere is the desire for sweetness stronger than in a man’s own country and nowhere is it more difficult to achieve.

Odysseus soon realises that home is not safe or steady. If he is to re-establish the order he remembers, he has to use all sorts of cunning and persuasion, and in the end even that is not enough. His longed-for sweetness clashes with the realities of imposing it on a place that has changed. The resolution the poem comes to is terrifying: Odysseus slaughters every one of the young men who have been living in his house and corrupting it. He leaves the palace littered with their bodies and his own skin slobbered with their guts – his thighs, Homer says at the end of the killing, are ‘shining’ with their blood – and then, with the help of his son, strings up the girls those men have been sleeping with, their legs kicking out, the poem says, like little birds which have been looking for a roost but have found themselves caught in a hidden snare. Odysseus thinks of it as a cleansing, a return to goodness, but the poem knows that the desire for sweetness has ended only in horror and mayhem. He thinks that order can be imposed by will; the poem knows that the vision of perfection brings war into a house and leaves it broken and bloodied.

It is a sobering drama, an anti-Arcadia, with a deep lesson: singular visions do not work; only by consensus and accommodation can the good world be made; returning wanderers do not have all the answers; and anything which is to be done in your own Ithaca can only be done by understanding other people’s needs and their unfamiliar desires. Complexity, multiplicity, is all and clarified solutions come at a brutal price.

So the nightingale has it. Newness is not a new quality. Ingenuity and inventiveness are central parts of life, human and non-human. Stay loose, it says; don’t rigidify; accept that you have inherited from the past many beautiful and varied ways of being. And once you know that, sing your song, which attends to the present, and is even a hymn to the present, to the long sense of possibility which has the past buried inside it. Elegy, which is a longing for an abandoned past, is not enough. Elegy, in fact, may do terrible Odyssean damage. It feeds off regret, and even though regret is beautiful and moving, it gives nothing to the future. Regret is a curmudgeon with a way of stringing up the innocent girls. This story, then, is a lyric, a song to what might be, not a longing for what has been.

Among the thousands of documents in the files of the Kent County Archives in Maidstone, there are two giant vellum pages, stitched together along the bottom edge with vellum strips and carrying the seals and signatures of eleven different individuals. Each page is over two feet wide and eighteen inches high, and both are covered from top to bottom in the tiny, exact but very clear handwriting of the clerk who drew them up.

The document looks as if it might be medieval, or perhaps the translation of something medieval, written on a burnished sheepskin, with the vast Gothic headline ‘This Indenture Tripartite’ painted across the top. It is in fact less than two hundred years old, an agreement made in May 1811 between Sir Horatio Mann, the owner of Sissinghurst, and a set of eight individuals, described as ‘Yeomen of Cranbrook’, who were renting the farm here. It is both an ancient thing, dripping in its medieval inheritance, looking like a treaty drawn up after Agincourt, and a modern one, an arrangement for the welfare officers in Cranbrook, which is what these men were, to take the farm so that the poor of the parish could live and work there: a job-creation scheme of a modern and enlightened kind.

When I first read this document, something else came bowling towards me. This lease, in its attention to the details of the land and the habits by which it was managed, was a voice from the old world. But it was also a summons to do things like it again. It was shaped by the attitudes which I felt Sissinghurst needed, a level of care and understanding which the late twentieth century had almost entirely abandoned. People had always accused me of ‘wanting to turn the clock back’. It was a phrase that seemed wide of the mark to me, dependent on the idea that the passage of time was a singular and univalent process, that the present needed to leave the past behind. I was not interested in turning the clock either backwards or forwards. I simply wanted to make the place as good as it could be.

The indenture, with its wavy upper edge, was a lease for twenty-one years, renewing another which the Cranbrook yeomen had made a few years earlier. The land they were renting at ‘Sissinghurst Farm’ was ‘by estimation 342 acres and a half’, in thirty-seven different parcels of arable, meadow and pastureland. The grass in the meadow was allowed to grow for hay; the pasture was to be grazed all year. There were eight acres of hops and extensive woodland.

All hedges had to be preserved ‘from the bite and spoil of cattle’. If any fruit trees died or were blown down, ‘other good and young fruit trees of the same or better sort’ had to be set in their place. Hedges had to be laid (every nine years) and good ditches made alongside them. They had to keep the buildings in good repair and pay for the window glass, lead-work, straw for any thatching and the carriage of materials. Mann’s steward agreed to provide out of the rent enough rough timber, brick, tiles, lime and iron for the work to be done.

This has a modern ring to it, a negotiated sharing out of tasks and costs. But in relationship to the land there was something much deeper, to do with a vision of cyclicality and self-sufficiency that seemed both extraordinarily and deeply primitive, laying down rules for this place which embodied almost total self-sustenance, and a clarion call for us.

First of all, the tenants were not allowed to carry away from the farm any of the farm’s own produce. Any hay, straw, fodder, unthreshed corn, compost, manure or dung ‘which now is or shall at any time during the said term grow arise or be made upon or from or by means of the said demised premises’ had to stay there. Sissinghurst’s fertility had to be kept at Sissinghurst because its long-term viability as a farm relied on those nutrients remaining to be recycled into the ground. The tenants ‘shall and will there imbarn stack and fodder out all such hay Straw and Fodder’. They were to see that the compost, manure or dung ‘shall and will in a good husbandlike manner [be] laid spread and bestowed in and upon those parts of the land which seem most to need it’. This is something the lease repeats insistently. ‘They shall and will constantly during the said term use plough sow manure mend farm and occupy the said demised lands and premises in a good tenantlike manner and according to the custom of the country in which the same are situate. And so as to ameliorate and to improve and not impoverish the same.’ Those words should be set up on a carved board at the entrance to the barn. They encapsulated, two centuries ago, exactly what I hoped for from my modern farm-and-restaurant scheme. This sense of self-enrichment was exactly what I had been stumbling after.

Here was a template for what we could do, for another way of looking at this place, which ran deep into its roots. It was essentially a cyclical vision. It did not imagine that next year would be very different from this, nor was it an exercise in progress. It felt for the health of the land in a way that understood it as a body, with all the implications of that organic analogy. It was not a fantasy of wholeness, but a working system, tied to earnings, rents, money and returns. It understood about the need for money on both sides, and the careful regulation of costs and responsibilities, but it did not single out money over all other aspects. It understood that money was one outcome, not the only one. And it understood that the land could only give what was put in. It was a picture of constancy and interrelatedness, not in any Wordsworthian ecstasy of revelation or understanding, but in a lease, a formal document made between the baronet and the yeomen of Cranbrook, drawn up by the lawyers. There, preserved in the county archives, was an invitation to the future. It was a world based on cud. A love of cud – that slow, delicious, juicy recycling of the nutritious thing – was what Sissinghurst needed. This was its unfinished history, its folding of the past into the future in the way that a cook stirs sugar into a cake.

What is it, then, that makes for beauty in a farmed place, which makes it stand out and apart from the beauty of the wild? It is at least in part a recognition of its fruitfulness, of the earth there being prepared to give some sustenance to the people who work it and work with it. But in each field, here or anywhere fields have lasted some time, there is something more than that. Each field is a small world, a particular vision, a definite history, cut off from the others and from the waste beyond them. Each is a history of care, as much as a person, or a tended animal. A field holds its own stories inside its boundaries and its essence is that the natural and the cultural have been allowed and even encouraged to come to an accommodation there. The field in that way is an act of symbiosis, the product of a human contract with the natural. In a field we are neither alien nor omnipotent. Fields belong to us but there are things beyond us in them. We shape them, make them, control them, name them, hedge them, gate them, plough them, mow them, reap them and plough them again but they are not what we are. They are our partners. Or at least that is their ideal condition. Industrialised farming is often painful and disturbing because it involves the breaking of that contract and the chemical reduction of partner to slave. It doesn’t need to be like that. It has usually, in human history, not been like that. The good farm is witness to a concordance between the human and the natural, a mutuality which as Wendell Berry, the Kentucky farmer and poet, has written, is the essence of music, goodness and hope:

Now every move

Answers what is still.

This work of love rhymes

Living and dead. A dance

Is what this plodding is.

A song, whatever is said.

I think that the farmed landscape is the most beautiful thing the human race has ever made. There is no need to be parochial about this: the great temperate belt, below the great forest and above the great desert, the humano-bio-sphere, girdling the earth, humanising it, is the great human habitat, the monument to symbiosis, to human and natural interpenetration. Is that human-devised skin wrapped around the earth no more than a product of an economic desire to survive, to get the food in? Surely not. More than the wilderness, it is our world, essentially co-operative and the great testament to what we are.

My particular problem at Sissinghurst – that I am both in it and excluded from it, that it is mine and not mine, that it has me by the heart but there is no possession there, that in some ways it is a source of life and meaning and in others a trap – all of this is only a heightened version of what our general relationship to place always has to be. We are all dispossessed. We are mortal, the earth is not ours and we are transient passengers, even parasites on it. And so almost by definition we must do things on it and with it which stand to be good in the long term. In my own mind, I have arrived at a particular phrase: the honourable landscape. Honour is the only thing that survives death. Honour is the denial of self and time. Honour understands about the virtue of the broad compass, of taking account as much as possible of what matters. Honour is not singular. It stands outside the claims of the ego, the desire to exploit, dominate or spoil. It understands about mutuality and the folding in of contradictory desires into a single variegated but integrated whole. It is a social and moral quality, founded on a self-renewing respect for the reality of others. It may be a hopelessly antiquated formulation, but that in the end is what I am interested in here.

I am leaving this story when it is quite unfinished. There are a thousand and one steps still to take. I sit beside the barn at Sissinghurst and look at the clouds streaming away in front of me to the north-east. That is what the future looks like too: avenues of bubbled possibility. The future here seems just as long as the past that extends behind it. Everything that Vita and Harold responded to when they came here nearly eighty years ago is still alive, but I also remember what John Berger wrote in Pig Earth: ‘The past is never behind. It is always to the side.’ That is true. The past is everywhere around me, coexistent with present and future, soaked into this soil but not sterilising it. There is no hierarchy. Past, present and future are all equally co-existent and Sissinghurst is becoming a place that responds to all three. And through that re-connection Sissinghurst will once again reacquire, I hope, a sense of its own middle, a confidence that it can turn to its own resources and find untold riches there. It will become, in the best possible sense of the word, its own place. That is the word to which this book has been devoted: place as the roomiest of containers for human meaning; place as the medium in which natural and cultural, inherited and invented, individual and communal can all fuse and fertilise. I don’t remember anything in my own life which has made me look at the world with such a surge of optimism and hope.