Running while skipping rope is a great form drill; you can’t overstride!

—MARK CUCUZZELLA, M.D.

Runners are obsessed with their feet. They agonize about buying the right kind of running shoes, while habitually scrutinizing the wear patterns on their shoe soles, looking for tell-tale signs that something might not be quite right with their foot strike. It’s this concern with foot striking that has made it one of the hottest topics in the current running form debate; but the reality is that the foot strike represents only a single aspect of one’s overall running gait, and it might not even be the most important.

It’s critical to remember that the foot can’t be looked at in isolation from the rest of the body; it’s connected to the leg, the legs are connected to the hips, the hips are connected to the vertebral column, and the vertebrae are connected to the head. All of the bones in these structures are linked together by ligaments, muscles and tendons, creating one big, interconnected chain where activity at one location can both influence, and be affected by, activity at any other. Got a pain in your knee? Well, the origin of that pain may have nothing to do with the knee itself, but might rather stem from an issue somewhere higher or lower in the chain (for example, the hips or the foot).

And let’s not forget your hands and arms! What you do with them can affect the torso, whose movements rotate the trunk, which can in turn influence what your legs are doing down below while you run. All of these structures function together to assist in your forward motion, and the coordinated whole must function properly should you want to move efficiently and injury free.

In this chapter we examine the running stride. Our approach once again is to start by addressing how the shod human running stride differs from that of the barefoot runner (and by proxy our unshod ancestors), and then to consider whether any of the differences observed might play a causal role in the epidemic of overuse injuries that plague contemporary running.

The Barefoot Difference

Multiple studies have attempted to document the biomechanical differences between barefoot and shod running strides. Unfortunately, it’s difficult to know if these studies provide useful information about what runners do when outside of a controlled laboratory environment. Is running on a treadmill a good simulation of running on the road? Is the gait of a shod runner who runs with his or her shoes off for the first time really representative of that of a seasoned barefoot runner? Is a study that looks at runners who pass by a camera or over a force-recording platform along a short indoor runway particularly relevant when compared to real-world running? Do any of these methodologies provide information about what a runner might look like on a mountain trail or at mile twenty of a marathon? All of these are valid questions, and must be kept in mind when interpreting existing scientific studies of running mechanics. Given these issues, as well as the widely varying methodological approaches employed by different researchers, results of published studies that have compared barefoot and shod running are sometimes contradictory. Nonetheless, some general trends or characteristics have been identified among barefoot runners as compared to runners in shoes.

• The foot is more plantarflexed (angled downward) prior to ground contact, and initial contact is more likely to be at the midfoot or forefoot.

• The ankle goes through a greater range of motion after contact is made.

• The knee tends to be more flexed at initial ground contact, but tends to go through less total range of motion.

• The shin tends to be oriented more vertically at initial ground contact.

• Peak pressures under the heel, midfoot, and big toe are lower

• The calf muscles show greater pre-activation in preparation for landing.

• Stride length decreases.

• Stride rate increases.

• Flight time, the amount of time both feet are in the air, is shorter.

• Vertical impact force is reduced.

• The rate of impact force application (loading rate) is similar to that seen in shod heel strikers, but is applied and absorbed in a different way. Instead of at the heel, impact in barefoot runners is typically applied at the forefoot and absorbed by the Achilles tendon and calf muscles.

To summarize then, barefoot runners tend to avoid or minimize heel striking; they take shorter, quicker strides; they bend the knee more at contact; and the stride is less impactful. On the other hand, runners in shoes tend to heel strike; they take longer, slower strides; they land with a straighter leg; and they generate greater impact when the foot strikes the ground. Though it’s fairly easy to identify distinctions like these that emerge in a research environment, it’s far more challenging to understand the significance of these differences or to provide advice to runners based upon these findings.

However, there’s indeed a degree of certainty that shoes change how we run—they encourage us to run in a way that is quite different than the form likely exhibited by our unshod ancestors. Whether these changes are for the better or for the worse remains an open question, and it is a topic that continues to be hotly debated by runners, coaches, biomechanical researchers, and health care professionals. With that said, let’s take a more detailed look at the human running stride and attempt to address the significance of some of the differences observed.

The Running Stride

From a biomechanical standpoint, a running “stride” is defined as the distance from the contact point of one foot to the next contact point of the same foot. In other words, a full stride incorporates three “foot-meets-ground” contacts—left-right-left, or right-left-right. A running stride consists of two major phases:

In contrast, a running “step” is the distance between two successive “foot-meets-ground” contacts. In this case, it’s right-left, or left-right, and is a function of the following:

From a practical standpoint, stride length and stride rate (number of strides taken per minute; also known as cadence) are important because they are the two determinants of running speed—increase or decrease either while holding the other constant and you will run faster or slower. Similarly, a fixed speed can be maintained with varying combinations of stride rate and length. If you observe ten people running at the same pace, some will probably have short strides and a rapid cadence, and others will have longer strides and a slower cadence. Furthermore, as discussed above, stride rate and stride length are two of the variables that are consistently found to differ between barefoot and shod runners—barefooters tend to take shorter, quicker strides, whereas shod runners usually take longer, slower strides.

The big, looming questions for runners are how these varying stride rate and stride length combinations affect efficiency, and whether the specific combination employed might exhibit a relationship to injury risk. As with almost every topic in the running world, opinions and advice abound, and optimal stride rate and stride length are among the most often discussed and debated aspects of running form. Should we run like the Looney Tunes Road Runner, legs spinning rapidly under our body, or should we run with a long, loping stride in order to maximize the ground covered with each step? In contrast with foot-strike types, there appears to be greater agreement concerning the stride: the excessively long-striding or overstriding runner tends to be less efficient, and places himself or herself at increased risk for injury.

Overstriding

When it comes to running, a long stride is often regarded as a thing of beauty. In his 1908 training manual titled Running and Cross-Country Running, the great British middle-distance runner Alfred Shrubb commented on this tendency, saying “Critics talk and write enthusiastically on ‘long, springing’ strides, of men who ‘move freely from their hips,’ and whose magnificently free action simply devours the ground. These critics mean well, no doubt, but they don’t do long-distance running any good.” Shrubb goes on to explain his reason for being critical: “For however pretty this stylish running may look, it speedily brings on leg-weariness. A man who ‘throws out’ his foreleg is bound to tire his knee-joints, while the man who strides high and long . . . will in the long run cover less ground at a greater exertion than the man who lifts his feet and body clear from the track for as short a while and as little as possible. A high, springing stride inevitably means a jarring return to earth, to say nothing of a straining of the joints employed.”

Shrubb, who set multiple distance-running world records despite having a stride that was referred to in his own book as “the most ugly in existence,” was not the only running great from the past to come down hard on the long stride. In his 1935 book titled Running, South African ultrarunner Arthur Newton, who often averaged 200 miles per week, wrote that “Every single way you look at it the long stride for a long journey is wrong. . . . The further you step, the further apart become the points where you are supported by your feet against the action of gravitation . . . the longer your stride the more you bob up and down while employing it . . . you must try to avoid excessive action of this sort as far as possible, as it means that you are using a whole lot of muscles and energy which are not in any way helping you along.”

It might be tempting to dismiss the writings of these old-time runners as nothing more than historical curiosities—after all, their records have now been eclipsed by runners employing modern-training techniques. However, opposition to the excessively long stride is still common today. For example, the “magic” number of 180 steps per minute is often thrown around these days as being the optimal cadence for a runner, with the implication being that most runners run with a step rate that is too low and thus a stride length that is too long (more on this in a bit). Similarly, one often hears that runners should shorten their stride by aiming to land directly under their center of mass. We’ll ignore for a moment the fact that there is no concrete evidence that 180 is optimal, and that landing directly under your center of mass is in most cases impossible, and instead consider what these oft-repeated nuggets of advice are attempting to correct: overstriding. Among the many things a runner can do wrong with their gait, overstriding is perceived almost universally to be one of the worst when it comes to both injury risk and running efficiency, and it is one of the most commonly observed gait flaws in the modern, shod runner.

Although it has been somewhat variably defined, the term “overstride” is generally applied in reference to the landing phase of running, and describes when ground contact occurs too far out in front of the center of mass of the body. The phrase “center of mass,” sometimes used interchangeably with “center of gravity,” is frequently stated in the running literature, both popular and scientific, and refers to the average location of the mass or weight of an object. For example, if you were to try to balance a pencil perpendicularly across your extended finger, the location where you could balance it evenly without it falling off would be the center of mass of the pencil. In a human standing vertically, the center of mass is located somewhere along the midline of the body extending from the head through the feet—functionally, it’s located roughly in the region of the hips. If you were to lean forward from the ankles while keeping your legs straight and feet planted firmly on the ground, your center of mass would move forward as well. Lean too far forward, and gravity acting vertically downward through your center of mass will cause you to topple over (note: gravity is a vertical force and will not pull you forward as suggested by some running-form schools).

Determining when a runner is landing too far in front of his or her center of mass is difficult in practice—how far is too far? As such, a more practical definition of overstriding is as follows: overstriding is when a runner reaches out excessively with the foot and lower leg such that at ground contact the ankle lands in front of a line drawn vertically through the knee (see Figure 8-1). The farther in front of the knee that the ankle falls, the greater the overstride.

Figure 8-1. Images of representative overstriding runners taken from a high-speed video recording of a 5-kilometer road race. All images represent the moment of initial contact between the foot and the ground—note that the ankle is well ahead of the knee in all three images.

Definitions based on forward reaching of the lead leg have been applied for decades. For example, Fred Wilt, a two-time Olympian (1948 and 1952 in the 10,000 meters) and former coach of the Purdue University women’s track and cross-country teams, wrote the following in his 1964 book Run Run Run: “The leading leg should never be stretched forward in an exaggerated effort to achieve a longer stride.” In their 1967 book Jogging, Bill Bowerman and W. E. Harris also advise against over-striding, writing that “Each foot falls just under the knee. Don’t reach out with the foot and overstride.” Similarly, Dr. George Sheehan asked the following question as part of his overuse syndrome “systems analysis” in his 1978 book Medical Advice for Runners: “Are you landing properly, with the knee bent and the foot never getting in front of the knee?” Unfortunately for many recreational runners, and even some elites, the answer to Sheehan’s question is all too often “no.”

Adding more complexity to his recommendation, Bowerman elaborated on overstriding and his vision of proper running form in an article from a 1971 issue of Sports Illustrated titled “The Secrets of Speed”:

When your foot first makes contact with the ground two fundamentals must be carefully observed. First, your foot should strike after it has reached its farthest point of advance and has actually started to swing back. Second, when your foot first strikes, the point of contact should be directly under your knee, not out in front of it, and as nearly as possible squarely beneath your center of gravity. Fortunately, both fundamentals are easy enough to comply with by keeping your knees slightly bent at all times and by not overstriding. If the foot hits the ground ahead of the knee, the leg will be too straight and will act as a brake instead of an accelerator. The entire body will be severely jolted with each stride. This creates fatigue, pain, and possibly eventual injury.

Bowerman covers lots of ground in this Sports Illustrated excerpt. He says that overstriding is bad, that it increases braking forces, that it jolts the legs and can increase injury risk. Hence, a runner should strive to land as close to directly underneath the center of mass as possible, and that the aim is to strike the ground after the foot has reached its farthest point of advance. Almost forty years later, running journalist and author Scott Douglas makes many of the same points in a 2010 issue of Running Times:

Overstriding means that your feet land significantly in front of your center of gravity. When this happens, you’re unable to make full use of your fitness, because you’re braking with every step. And you might soon be breaking with every step, in that overstriding amplifies the already-strong impact forces of running and therefore can contribute to more strain on your bones, muscles, and ligaments.

Apparently, many runners have not gotten the message. In slow-motion video clips of typical non-elite runners in a race, it’s quite common to observe people landing with nearly straight legs, feet extended well in front of the knee, and a foot that is angled upward toward the sky. Furthermore, many runners violate Bowerman’s directive to not let the foot contact the ground before the lower leg has finished its forward swing— in fact, some runners, particularly when fatigued, will actually skid forward into a landing. (If you have extensive wear on the outer-rear margin of your shoes, you might be a scuffer of this sort.)

So how is it that after more than 100 years of athletes, coaches, and writers shouting warnings about the risks of overstriding, this nettlesome gait flaw is still so prevalent in just about any road race? Part of the reason, one can certainly suspect, is running shoes. For the past several decades, running shoes have been designed for the specific purpose of reducing impact, which is a major outcome of overstriding. Quite rightly, runners who overstride and pound the ground with their heels need cushioning under the rear portion of the foot. As a result, heel cushioning has become more elaborate, and cushioning “technology” in the heel requires space that has necessitated that heels become even larger still. And herein lies the problem—the rear portion of the sole of a shoe with a 12mm cushioning differential between the heel and forefoot extends both far below and typically well behind the actual heel of the foot. This particular footwear construction virtually guarantees that contact characteristics will differ from barefoot running because there is simply more shoe to get in the way of a runner’s natural stride.

Following Bill Bowerman’s advice to contact the ground after the leg has started to swing back is difficult in shoes with a large, cushioned heel because the heel can catch the ground before swing-back can even begin; and once the heel catches it forces the forefoot to slap downward as the foot is torqued about the ankle. As the cushioned heel gets larger and larger (for example, by adding springs or other gratuitous “impact absorbing” gadgets), it’s probably even more likely that a runner will overstride. It’s a vicious cycle where the overstride calls for cushion, and cushion allows the overstride to become even more pronounced, to the point where it is hard to avoid. Just as Peter Cavanagh suggested back in 1980 that thickening of the cushioned heel of running shoes might have contributed to rearfoot instability and thus the rise of pronation control technology, raising the heel might also be encouraging a more impactful gait, necessitating ever larger amounts of cushion. In other words, modern running shoes may be creating problems that require “more shoe” to correct. It’s a catch-22.

Dr. Steven Robbins, an M.D. and associate professor of mechanical engineering at Concordia University in Montreal, has written extensively on the effects of cushioning and footwear on running gait, and in a series of papers from the late 1980’s and early 1990’s he outlined a number of mechanisms by which running shoes alter one’s stride. He summarized many of these points in a 1990 article in the journal Sports Medicine.

Robbins suggested that an extremely soft, cushioned running shoe encourages pre-emptive stiffening of the leg prior to landing as a runner searches for stability and attempts to prevent the foot from rolling inward or outward on the compressible sole after contact is made. In other words, running in a soft, cushioned shoe causes you to tense certain of your leg muscles in preparation for landing since you know your foot is about to collide with an unstable surface. This response is similar to how your body reacts to running on surfaces of varying hardness—the softer the surface, the more you stiffen your legs when your foot lands (try running on gym mats or a trampoline and see what happens). This response could in part explain why runners in heavily cushioned shoes tend to both land on their heels and have straighter legs at contact. In support of this hypothesis, a study published in 2003 in the Journal of Biomechanics by Vinzenz von Tscharner and colleagues from the University of Calgary demonstrated that shod runners exhibit more intense preactivation (or pre-firing) of the tibialis anterior muscle on the front of the shin prior to ground contact than barefoot runners—this muscle is responsible for lifting the front portion of the foot up (dorsiflexion) prior to a heel strike. Altering what is on your feet thus changes the action of your muscles, and these changes are initiated before the foot even contacts the ground.

In addition to creating instability by putting a soft landing surface under the foot, Robbins emphasized that shoe soles rob your feet of critical sensory input from the ground surface, and he believes that this can have a dramatic effect on running form. For example, he thinks that one will modify the interaction between the foot and the ground in order to minimize painful sensations caused by surface irregularity or the presence of ground debris like pebbles or sharp twigs. As anyone who has tried to run barefoot on asphalt or concrete knows firsthand, initial attempts (depending on distance) will often result in serious blistering of the skin on the bottoms of the feet. Some of this might be due to a lack of conditioning (the bare skin is simply too tender, especially if one has been wearing shoes since childhood). But the skin abrasion that occurs might also be caused by a lack of behavioral adaptation. Robbins indicates that due to the highly sensory nature of the soles of the human feet, barefoot runners learn to avoid shearing between the foot and the ground by adapting their stride to minimize friction. Repeatedly skidding forward into a landing would be quite damaging for a barefoot runner! What many barefoot runners tend to do instead is land just as described by Bowerman—after the foot has reached its forward-most swing or even after it has just started to come back. In watching slow-motion videos of barefoot runners on asphalt, it often seems as if the foot pauses in the air for a split second just before it touches down—it’s as if the foot is waiting for its forward velocity to match that of the rest of the body before contacting the rough surface below. A good way to visualize this is to think about the motion of the foot when propelling a scooter or skateboard—you don’t want it to first plow forward into the ground, then reverse direction and start pushing. The friction generated might not hurt if you’re wearing shoes, but you can be sure that doing it regularly would rapidly wear down the sole.

If Robbins is correct, then the form adaptations made by barefoot runners are not geared solely toward managing impact, but also include protective mechanisms aimed at preventing damage to the skin on the sole of the foot. Putting on shoes of any type (even the most minimal) removes the need for this protective response, and this could explain why running form of barefoot runners changes in certain noticeable ways— longer stride, reduced cadence, longer flight phase—even when they put on ultra-minimal shoes like the Vibram FiveFingers. Even though there are now plenty of new barefoot-style and minimalist shoes without much or any cushion, making a shoe that allows similar plantar sensation as going completely barefoot is simply not possible. Furthermore, any protective covering on the sole, no matter how thin, is going to dramatically reduce friction between the skin and ground. As a result, it is quite unlikely that any form of footwear will perfectly replicate what it is like to run barefoot.

Consider the irony: Bill Bowerman, who was a co-founder of Nike, advocated that runners should avoid doing all of the things that modern cushioned shoes with beefed-up heels encouraged them to do with their form. The ideal form, he maintained, is instead more typical of speedy elites and those who regularly run barefoot. Although the straight-legged heel strike is common among shod runners, unless you’re running on an exceedingly soft surface (such as sand), it’s not something you would likely do for any length of time if you were barefoot. Though some barefoot runners do in fact heel strike, and some do overstride with a forefoot strike (overstriding can occur with any type of foot strike, and a forefoot overstride can be just as problematic), it’s extremely rare to see a barefoot runner who combines a pronounced overstride with a significant heel strike—to do so would be far too jarring on the heel bone and lower leg. The combination of overstriding and a massive heel strike seems to be a modern phenomenon, and it might just be that this unnatural pairing is causing us harm.

Is Overstriding Bad?

It’s all well and good to posit that gait adaptations caused by shoes might be a cause of some running injuries, but speculation should not be the basis upon which runners decide to ditch their shoes or modify their stride. A better approach is to consider the evidence that suggests that overstriding and related gait characteristics are in fact problematic, and to then explore approaches to overcoming the overstride.

Let’s take a look at two studies that support the notion that longer strides increase joint loading, and thus might increase injury risk:

Stride Study #1

A 1998 article in the journal Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise discusses in depth the relationship between stride length and impact absorption in running. The authors of the article, lead by Dr. Timothy Derrick from Iowa State University, point out that when a runner’s foot makes initial contact with the ground during the landing phase of the gait cycle, the body rapidly decelerates during the collision, and a shock wave is transmitted through the body. Because it is imperative to keep the head stable in order to maintain the ability to see straight and prevent the brain from rattling around in the skull, the body has built-in mechanisms that attenuate or diminish the magnitude of this shock wave before it reaches the head.

Shock-dissipating structures in the human body include the bones and cartilage in the feet, legs, hips, and vertebral column, and the muscles and tendons that attach to your skeleton. Because of both their elasticity and their ability to adapt contraction strength to the demands of the situation, your muscles are the most effective shock absorbers. As impact is applied at the foot and your joints begin bend, the muscles around the rotating joints are tensed in order to prevent each joint from collapsing. In this process, they “absorb” some of the impact energy. This is why you aim to land with bent legs rather than straight legs when jumping down from a height—better to brace your fall with your leg muscles rather than your leg bones. A straight-legged landing is far more likely to be jawjarring and teeth-rattling!

Derrick and his colleagues’ goal with their experiment was to determine how decreasing and increasing stride length from a runner’s naturally chosen value at a given speed might affect impact energy absorption and thus shock attenuation at the ankle, knee, and hip. In other words, could an alteration of stride length affect how one manages the impact shock wave as it races from the feet up to the head, and if so, what implications might this have for injury risk?

To conduct the experiment, the researchers attached shock sensing accelerometers to the shins and foreheads of their subjects—this would allow them to estimate shock dissipation from the lower leg to the skull. Each runner ran across a force plate at his normal, naturally chosen stride length, and then at (plus or minus) 10 percent and (plus or minus) 20 percent of the normal stride length (using longer or shorter strides than he would freely choose). What Derrick’s team found was that as stride length increased from normal, shock magnitude increased and progressed further up the body from foot to head—this resulted in increased impact energy absorption by the knee and hip. As stride length decreased, impact energy absorption at all three joints—the hip, knee, and ankle— decreased significantly. Of particular interest is the fact that the specific way impact energy was dissipated by the joints was dependent on stride length. Though all three joints contributed to impact energy absorption while running with a stride 20 percent longer than what was normal for the runners, the long stride placed a disproportionate fraction of the work on the knee, which is the most commonly injured joint in runners. In contrast, when running with a stride 20 percent shorter than normal impact absorption was shared almost equally by the ankle and knee, and the hip contributed very little.

The results of this study indicate that running with a long stride places greater stress on the muscles and connective tissues that support the knees and hips. Not only could this increase risk of overuse injury, it also requires the large muscles around these joints to be more metabolically active. Studies have indeed shown that longer strides are associated with greater energy utilization (and thus reduced efficiency), whereas runners can increase stride rate by as much as 10 percent (and thus shorten their stride) without incurring a metabolic penalty (more on this later). If speed over a short distance is the goal, a long stride may not be a big problem, but over the course of a marathon or an ultra a long stride could be a recipe for disaster.

Stride Study #2

In 2011, Dr. Bryan Heiderscheit, a physical therapist and associate professor in the Department of Orthopedics and Rehabilitation at the University of Wisconsin, published a study with colleagues in the journal Medicine & Science in Sport & Exercise that to a degree reproduced but also expanded upon the research done by Derrick’s team. Heiderscheit noted that increasing stride rate and thus lowering stride length appears to have positive benefits for joint loading, but that increasing stride rate too much has negative impacts in terms of efficiency. Thus, he conducted a study to look at the effects of more moderate modifications of step rate/ length on running mechanics and joint loading, and he looked at loading over a longer period of the stance phase. (Authors’ Note: the phrases “step rate” and “stride rate” are sometimes used interchangeably, which can be confusing. Step rate is the number of steps taken per minute; stride rate is the number of strides taken per minute. Since each stride is composed of two steps, step rate is equal to two times stride rate.)

In the Heiderscheit study, forty-five recreational runners ran on a treadmill (each wearing his or her own training shoes) at step rates both 5 percent and 10 percent below (slower cadence) and above (faster cadence) their normal, freely chosen step rate. All trials were run at the same speed (a “moderate intensity” pace chosen by each individual). They concurrently measured forces underfoot, and made a variety of biomechanical measurements of the runners at the various step rates.

With a step rate increase of only 5 percent relative to the naturally chosen step rate, this is what the study found:

Heiderscheit’s team also found that in addition to the changes listed above, a step rate increase of 10 percent resulted in the following:

Generally speaking, most of the above variables changed in the opposite direction when step rate was decreased by 5 or 10 percent, and somewhat surprisingly, the ankle only showed increased loading when step rate was reduced by 10 percent from normal. Thus, running with shorter, quicker steps tended to reduce joint loading, whereas longer, slower steps increased loading of all three of the major joints in the leg.

Looking at these results, it seems like running with shorter, quicker steps provides much positive benefit with little negative consequence beyond a slightly greater perceived exertion if step rate is increased by 10 percent from what is normal for that runner. One notices that loading of joints is reduced, braking force and up/down movement are reduced (both of which can be linked to improved efficiency), and several biomechanical measures associated with injuries are lessened. As an example of the latter, Heiderscheit writes that excessive hip adduction and internal rotation have been associated with knee injuries and iliotibial band syndrome, and suggests that “running with a step rate greater than preferred . . . may be useful in the clinical management of running injuries involving the hip.”

The Heiderscheit study concludes that “subtle changes in step rate can reduce the energy absorption required of the lower extremity joints, which may prove beneficial in the prevention and treatment of running injuries,” and that the “knee joint appeared to be most sensitive to changes in step rate.” Furthermore, the authors highlighted that “many of the biomechanical changes we found when step rate increased are similar to those observed when running barefoot or with minimalist footwear.”

On the Runner’s World Peak Performance blog, Amby Burfoot interviewed Heiderscheit about his study. He asked him what he thought would have happened if his subjects had worn racing flats instead of their training shoes, and Heiderscheit responded that: “I’d guess, and this is just speculation, that they wouldn’t run the same as in the training shoes. I think they would have selected a preferred stride rate close to our plus five-percent condition.” Burfoot later asks whether “thick, cushioned shoes” encourage runners to take a longer stride, to which Heiderscheit responded that there is lots of variability, but that it “seems like a reasonable conclusion.” Furthermore, just as Bill Bowerman emphasized that landing should occur “after (the foot) has reached its farthest point of advance and has actually started to swing back,” Heiderscheit also stressed the importance of the final moments before ground contact: “A lot of the big action happens at the very end of the stride. Some people fall forward onto their extended foot, while others begin to reverse their foot action before they put the foot down. Thicker shoes probably encourage runners to fall forward onto them.”

What’s important to remember in considering the results of studies like those conducted by Derrick and Heiderscheit is that though both empirically observed what appear to be positive changes in association with a shorter, quicker stride, these studies do not answer the question of whether such changes actually reduce injury risk. Heiderscheit was very clear about this in his interview with Burfoot, saying that “We decided against pushing the shorter strides harder at this point because we don’t have good injury results yet.” But based on his own clinical experience treating injured runners, Heiderscheit did say that “if we shorten their strides, a lot of their problems go away.” Thus, there is no guarantee that a shorter stride is a cure all for every running injury or that it will even consistently fix a specific problem like knee pain in every runner who suffers from it. However, the results of these studies do suggest that stride manipulation is a potentially useful tool in the treatment of running injuries, and the positive benefits seem to be accrued by adapting patterns away from those encouraged by the modern running shoe.

Pounding vs. Repetition—Which is Worse?

While increasing stride rate and thus decreasing stride length has been found to reduce loading of the joints, running at a higher cadence requires one to take more steps to cover the same distance. This raises the question of which is more detrimental to the body: a lower impact stride that must be repeated more times over a given distance, or a higher impact stride that can cover that distance with fewer repetitions?

In a 2009 study published in Medicine and Science in Sport and Exercise that looked at the risk of stress fracture as it relates to stride length, Dr. Brent Edwards of the University of Illinois at Chicago and colleagues determined that reducing stride length by 10 percent should theoretically reduce the risk of suffering a tibial stress fracture, and that “the benefits of reducing strain with stride length manipulation outweigh the detriments of increased loading cycles associated with a given mileage.” Furthermore, the study concluded that “these benefits become more pronounced at higher running mileages.” Though more research needs to be done on this topic, initial results support the idea that the load-reducing benefits of increasing stride rate outweigh the risks of having to cycle through a greater number of strides on each run.

On Anecdotes and the Running Stride

Let’s temporarily move away from the hard science and address a topic that’s certainly less empirical and data-driven: anecdotal evidence. While these “findings” are often dismissed as unscientific, it does not mean that they have little value. Subjective experience is what many of us have to go on. We might like a certain shoe or feel that a technique “cured” a chronic injury. Furthermore, when there’s mounting anecdotal evidence about a particular issue or problem, this should be a sign for further study. Brian Heiderscheit told Amby Burfoot that one of the reasons that he conducted his study on stride-rate manipulation was his clinical observation that patients sometimes reported that their knee-injury symptoms improved when they ran faster, and faster running is typically coupled with a higher stride rate and possibly changes in landing characteristics. This is an ideal example of how anecdotal observations can stimulate more detailed scientific study, which in turn can aid in the development of treatment strategies.

Anecdotes have played a big role in fueling the recent barefoot running trend and consumer interest in minimalist footwear. You’ve probably read about or heard fellow runners claiming that switching to barefoot running or a barefoot-style stride made all of their injuries go away. What they may not reveal is that sometimes new and different injuries do appear (often to bones, muscles, ligaments or tendons associated with the ankles or feet), but let’s assume that these individuals are being honest (given the number of these reports, surely some of them are) and relate these anecdotal reports to the science just discussed. As we noted at the beginning of this chapter, one of the major differences that has been consistently observed in comparisons of shod vs. barefoot runners is that the barefooters tend to adopt a shorter, quicker stride. Thus, we might speculate that one of the ways that running barefoot or with barefoot-style form might help some people overcome injury is that it facilitates a change in running gait, and that change alters the way that forces are applied to the joints. The studies by Derrick and Heiderscheit provide plausible mechanisms by which this might occur—running with a shorter, quicker stride seems to take some of the load off the knees and hips, so those suffering from injuries associated with these joints may experience relief when their stride shortens up even just a small amount.

The next step in the process of scientific investigation is to actually put stride length modification as a treatment strategy to the test—try it out on a group of injured runners and see what happens. According to an August 2010 article by Alex Hutchinson in the Globe and Mail, Heiderscheit has been doing just that by conducting a trial that compares stride rate modification to standard care for the treatment of knee pain and iliotibial band syndrome. It will take awhile for the results to fully materialize, so it’s currently up to each runner and therapist to individually decide whether they find existing evidence of benefit sufficient, or whether it’s better to wait for concrete results on injury outcomes. For the perennially injured runner who has nothing to lose though, doing a bit of experimentation with form or footwear either on his or her own or under the guidance of a coach or physical therapist seems like an easy choice— when the alternative is not running at all or being miserable when you do so, why not try something different?

The Need for Speed

You’ve probably noticed that we’ve written little in this book about speed— the omission is intentional. Though running fast may win races and satisfy individual performance goals (who doesn’t like setting a new PR), speed increases forces and thus increases injury risk.

“Running to compete” has been identified as a risk factor for injury in runners, and if you make a decision to compete in races and chase time goals, then you must accept that there is some risk associated with doing so. Elite athletes accept this risk every day—to be able to perform their best in competition, they run a very fine line in attempting to maximize the benefits of training without pushing so hard that they get hurt. But, elite athletes are usually paid to train (it’s their job), or they are on scholarships. Furthermore, they typically have support networks, trainers, massage therapists, coaches, and so forth to keep their bodies in highly competitive shape. The elite athlete thus has both needs and means that are very different than those of the weekend warrior.

So, for the majority of runners who run for health, fitness, and enjoyment and perhaps like to let loose in the occasional local 5K (and who have never had the opportunity to sit in a cryosauna, or sleep in a high-altitude simulator), what are the best ways to incorporate speed without getting hurt?

First and foremost, speed should be embraced like any other change in training—gradually and progressively. Don’t head out to the track and attempt to knock out ten laps at maximum speed on your first time out! Build slowly and learn to feel comfortable using a faster stride. Regarding the latter, be aware that running faster is usually accomplished initially by adopting a longer stride, so avoid the temptation to lengthen stride by reaching out with the lead leg. If you watch elite runners running fast, they typically elongate their stride on the backside by extending their hip more, which results in the foot and leg trailing further behind the body. This can be difficult if you have tight hip flexors or weak glutes/hamstrings (as most of us who sit at a desk all day probably do), so some flexibility and strengthening work might be advisable. Also, avoid the temptation to launch yourself into the air at too high an angle with each stride—excessive vertical movement wastes energy by requiring your muscles to work harder to support your weight as you come back down.

Although there are risks involved, one of the positive benefits of running fast is that it’s a great way to fine-tune your stride. Mistakes are more noticeable when you’re running at high speed, particularly if you’re wearing racing flats or a similar minimal shoe, and speed work will allow you to feel what it’s like to run at a higher cadence.

You might consider starting with speed work by just incorporating a bit of faster paced running at the end of your runs (perhaps barefoot on a track infield). If you find that to be of benefit, you can start to explore more intense speed workouts like track intervals. Regardless of what you choose, the same message applies: always be careful.

Is There an Optimal Stride Rate?

Let’s say that you know that you’re an overstrider—perhaps your running partner has commented on how you thud the ground when you run, or perhaps you spot a race photo of yourself hitting the ground with an extended knee. Suppose you also have a chronic injury history that you suspect might be related to your less-than-ideal gait, or maybe you think that the braking forces that you generate are holding you back from your next PR. How do you fix this?

There is no shortage of available advice and information on how to go about retooling your stride. In fact, form coaches seem to be popping up all over, and there are entire books and DVD series that provide detailed instruction on how to retrain your gait (for example, Chi Running, Evolution Running, POSE). Each form approach has its own idiosyncrasies, and a comparison among them or consideration of their relative merits is beyond the scope of this book. Our own personal take is that we all learn differently, and if you think an informational guide or accredited coach might be useful then do a bit of research on the options and go for it! However, there’s no reason that form change can’t be accomplished on your own if you have the desire and willingness to expend a bit of time and effort.

Should You Attempt to Run Like the Elites?

One approach to learning about good running form is to watch the elites— they run for a living and have spent more time fine-tuning their form than the vast majority of recreational runners. However, a few things should be kept in mind when trying to emulate the form of elite runners.

First, and most obviously, elite runners in a race are running very fast, and form changes with speed. It makes little sense for a recreational runner who puts in most of their miles at an 8:00 or 9:00 per mile pace to attempt to perfectly mimic the gait of an elite 10,000-meter specialist running at a sub-5:00 per mile pace. Most of us would be better off emulating the relaxed form they employ during their victory lap!

Second, form among elite runners is variable. Alberto Salazar, who won the Boston Marathon once and New York City Marathon three times in the early 1980’s, was widely believed to have succeeded despite his form rather than because of it. So even elites may not be perfect role models. Should the average runner mimic the head-bob of Paula Radcliff? Probably not, even though she does happen to own the women’s marathon world record. Emil Zatopek was one of the greatest distance runners of all time. But here’s how New York Herald Tribune sports columnist Red Smith described his form: “He ran like a man with a noose around his neck . . . the most frightful horror spectacle since Frankenstein . . . on the verge of strangulation; his hatchet face was crimson; his tongue lolled out.” Another newspaper scribe wrote, “He ran as if his next step would be his last.” But Zatopek, a threetime gold medalist in the 1952 Helsinki Olympics, had a ready-made answer for his critics: “I shall learn to have a better style once they start judging races according to their beauty. So long as it’s a question of speed then my attention will be directed to seeing how fast I can cover the ground.”

There are many factors that make elites capable of throwing down times that the rest of us could only dream of—these include inherent aspects of their anatomy and physiology, training background, motivation, mental toughness, VO2 max, capacity to endure pain, and so on. Form is just one part of the picture when it comes to elite running success, and it may be a very small part.

Taking this a step further, even if we take a group of elites who experts might classify as having “ideal” form, careful examination will reveal variation among them. Some carry their arms high, some carry them low. Some keep their torso upright, some lean forward a bit. Some spend a bit more time with both feet airborne, some stay closer to the ground. Some heel strike, some land on the midfoot, and others land on the forefoot. There are commonalities among elites that may suggest general patterns, but looking at any single elite’s running form as a model of absolute perfection that should be copied is a mistake. Running biomechanist Peter Cavanagh made this very point back in 1980 in the book The Sweet Spot in Time by John Jerome: “It doesn’t work, for instance, to tell the novice to imitate (Bill) Rodgers . . . Running style, or performance in any sport, eventually boils down to the way you adapt to your own anatomy, your own physiology, to the peculiarities of your own body.”

The take-away message for all runners is that each of us is unique—and this applies to the recreational runner as well as the elite. Ultimately, the key is finding the best form for your individual body—whether that’s the form that lets you run fastest, most efficiently, or with least chance of injury, that decision is up to you.

You have probably heard or read somewhere that the ideal running stride is to land with the foot directly under your center of mass and to run with a cadence of 180—both of these are aimed at reducing stride length and thus correcting an overstriding gait. Is there any evidence to support this advice? Let’s start with center of mass. Unless you are accelerating, like say a sprinter coming out of the blocks, you cannot land directly under your center of mass when you run. Says gait expert Jay Dicharry: “At steady state, the foot does (and should) contact in front of the center of mass.” The exact distance that the foot lands in front of the hips varies for sure, but it is always out front. Thus, thinking about landing under your center of mass is a great cue to help get your stride to shorten a bit, but it never happens in reality.

Next let’s address the “magic 180.” It’s not uncommon these days to hear people say that a stride rate of 180 steps per minute is optimal. Witness this passage from an article titled “Stride Right” by two-time Olympic marathoner Ed Eyestone in the September 2011 issue of Runner’s World:

Years ago, researchers determined that elite distance runners ran at a rate of about 180 strides per minute. Indeed, eminent exercise physiologist and coach Jack Daniels tallied the stride rate of every runner in every distance event at the 1984 Olympics in Los Angeles. He found that in events longer than 3000 meters, every runner save one had a stride rate of 180. The outlier had a paltry 178.

While it’s not easy to overcome biology, you can move closer to the optimum 180 strides per minute—with practice . . .

As Eyestone’s passage points out, this number can be traced back to famed coach Dr. Jack Daniels, who in his classic training manual, Daniels’ Running Formula, published an observation that elite runners at the 1984 Olympics tended to run at a stride rate of 180 or more steps/minute. Yet it’s worth noting that this is actually not the first time that the number 180 has been mentioned in relation to running cadence—Arthur Newton recommended a 180 cadence in his 1935 book Running. Nonetheless, Daniels is generally considered the father of 180. Based on his observations at the Los Angeles Olympics, which included runners competing in events ranging from 800 meters to the marathon, he also found that the rate “doesn’t vary much even when they’re not running fast” or in events from 3000 meters on up. Conversely, Daniels writes that when he works with new runners, few if any have a stride rate of 180 or more. He suggests that these long, slow striders are at increased risk for injury, and writes that “the slower you take steps, the longer you’re in the air, and the longer you’re in the air, the higher you displace your body mass and the harder you hit the ground on landing.” This occurs because a slow cadence must be compensated for by a longer stride to maintain a given speed (remember: speed = stride rate × stride length). He advocates that runners work on a “shorter, lighter stride,” with the end goal being that their running will become more efficient and they will be less prone to impact related injury. Sounds a lot like what Shrubb and Newton were saying back in the first half of the twentieth century, doesn’t it!

Unfortunately, Daniels’s findings have been misinterpreted by many runners and coaches who steadfastly believe that all runners should aim to run at exactly a 180 cadence at all times. Daniels never took such a rigid position regarding cadence. Indeed, he provides this advice in his book: “We often talk about getting into a good running rhythm, and the one you want to get into is one that involves 180 or more {our emphasis} steps per minute.” Essentially, Daniels feels that most runners have a cadence that is too slow, and that they would benefit from speeding it up a bit. An inflexible adherence to 180 steps per minute ignores the fact that cadence is known to change with speed and is probably influenced by other factors. What’s more, despite the frequency with which the 180-cadence mantra is repeated, there does not even appear to be any evidence that the 180 number is optimal for every person. Rather, the existing evidence suggests that each individual has an optimal cadence range of their own, and that the primary factor that determines optimal cadence is efficiency. Put simply, most runners seem to choose their individual cadence in order to minimize the energy that they expend when they run.

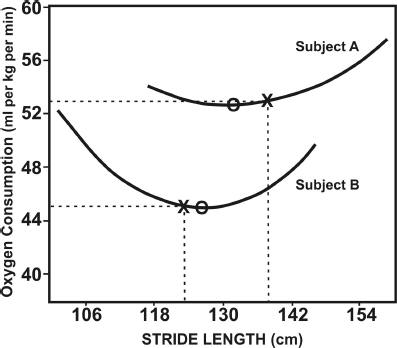

In 1982, Peter Cavanagh and Keith Williams published a classic paper titled “The Effect of Stride Length Variation on Oxygen Uptake During Distance Running” in the journal Medicine and Science in Sport and Exercise. Their goal was to determine how a given runner chooses the specific combination of stride rate and stride length that he employs when he runs. The researchers were intrigued by the idea that runners might subconsciously choose these parameters in order to run with a combination that minimizes energy expenditure at a given speed.

In order to test this hypothesis, Canavagh and Williams had ten experienced male runners run on a treadmill at a pace of 7:00 per mile. They had the runners run at their freely chosen stride rate and length, and using this value as a baseline, had them both increase and decrease stride length by 6.7 percent, 13.4 percent, and 20 percent from their freely chosen values (they used a metronome to vary stride rate, which resulted in the desired change in stride length since speed was held constant). During each running session at each stride length, they recorded oxygen consumption as a measure of energy expenditure (standard procedure in studies of this type). In doing so, they were able to observe how energy expenditure changed as stride length was varied above or below the preferred value for each individual. A higher oxygen consumption at a given stride length indicated that a greater amount of energy was being expended (in other words, the runners were less efficient at the experimental pace).

What Cavanagh and Williams found was that the freely chosen combination of stride rate and stride length was indeed the most energy efficient for most of the runners that they looked at. That is, having the runners artificially increase or decrease their stride length caused them to consume more oxygen (use more energy) than when they were allowed to subconsciously choose their own stride length. Viewed in graphical form (Figure 8-2), plotting energy expenditure against stride length yielded a U-shaped curve for each runner, with freely chosen stride length tending to fall right near the bottom of the U, which is the most economical position.

Figure 8-2. Graph adapted from Cavanagh and Williams (1982) showing the relationship between stride length and oxygen consumption (energy expenditure) for two individual subjects. X’s indicate normal, freely chosen stride length for each individual, O’s indicate optimal stride length for each individual. Note that oxygen consumption at the freely chosen stride length was fairly close to optimal, indicting that the runners tended to run with a stride length that minimized energy expenditure.

In addition to the above relationship, the researchers observed considerable variation among runners in both minimum energy expenditure at the experimental speed, as well as the specific combination of stride rate and stride length employed to minimize energy expenditure. In other words, most runners chose a combination of cadence and stride length that was individually most efficient, but there was no single combination that was most efficient for all of the runners. The upshot of this is that attempting to force all of these individuals to run at the same cadence (for example, 180) would make very little sense.

When looked at on an individual level, the results of Cavanagh and Williams’ study yield some interesting findings. For example, they found that the runner with the longest legs had the shortest stride, and that the runner with the shortest legs had among the longest strides. One could imagine a long-legged runner taking short, choppy steps, but how could a short-legged runner come out near the top in a stride length comparison? Details are not provided, but one might possibly suspect that Mr. Shorty was doing some combination of extending the leg behind his body further and generating greater propulsion on takeoff, spending more time in the air during flight phase, or extending the foot farther forward on landing.

When Mr. Long Legs and Mr. Shorty were removed from the study, Cavanagh and Williams still found no strong relationship between leg length and optimal stride length, which indicates that the commonly held belief that longer legged runners take longer strides was not supported by their data. “It is not in general possible to predict optimal stride length in a population on the basis of leg length” writes Cavanagh. This comes as a bit of a surprise since just as individuals of above average height are often assumed to be “born” basketball players, individuals with long legs are often assumed to have a natural advantage when it comes to distance running. The notion that leg length is a poor predictor of stride length has since been supported by additional studies, and thus it’s not just a fluke observation of a single experiment. For example, Cavanagh himself did a follow-up study with Rodger Kram, now a biomechanist at the University of Colorado, in a 1989 issue of Medicine & Science in Sport & Exercise in which they found only a weak relationship between leg length and stride length. Based upon this result they concluded that “distance running coaches would be unwise to attempt any intervention involving alterations in SL (stride length) based on body dimensions.”

Another interesting finding from the Cavanagh and Williams study was that seven of the ten individuals studied employed strides that were longer than that predicted to be optimal. Of these, three overshot their optimal stride length by a considerable distance of 5 centimeters or more. Interestingly, in the study discussed earlier, Bryan Heiderscheit found that an increase in cadence of 5 percent from an individual runner’s preferred value reduced stride length on average by about 5 centimeters. By combining the findings from these two studies (which is admittedly speculative), 30 percent of the runners from Cavanagh and Williams’ study ran with a considerably longer than optimal stride length in terms of efficiency, and their strides were probably more impactful on their joints than if they ran at their optimal stride length. These would seem like obvious candidates for a bit of form work, and once again emphasizes why variation among individuals is always critical to take into account.

The authors conclude by stating the following: “The major implication of the results of this investigation is that well-trained runners are likely to run with a combination of SL (stride length) and SF (stride frequency) which is extremely close to their optimal condition,” with the optimal condition being the one that requires the least expenditure of energy. The results of this study have left a lasting impression among coaches and running researchers, and it’s not uncommon to hear experts claim that form change should not be pushed since runners automatically choose the optimal stride for their own body. There are a few problems with this viewpoint. First, most runners in Cavanagh and Williams’ study chose a near optimal stride length, but not all—30 percent of them had stride lengths that were over 5 centimeters longer than optimal. Second, all of the subjects that Cavanagh and Williams studied were “well-trained” runners—all were running an average of 40 to 110 miles per week at the time the study was conducted. Thus, these were very experienced runners who’d had plenty of time to feel out their gait and converge on what might be their personal optimal stride. It’s difficult to know if the same could be said for new-to-the-sport recreational runners who run ten to fifteen miles per week and are training for their first half-marathon. Cavanagh, one of the most thoughtful, conservative, and precise scientists to study running mechanics, points this out, saying “It would be of considerable interest to replicate this study with a group of beginning runners to determine if their deviations from the optimal conditions is greater than the group of well-trained or experienced runners used in this study.”

Although not necessarily conducted on beginning runners, Dr. Joseph Hamill of the University of Massachusetts published a paper in 1995 in the journal Human Movement Science in which he and colleagues performed a similar analysis to Cavanagh and Williams on ten college students who were “physically active at the time of participation in the study but not necessarily training.” They found that energy expenditure was actually lowest on average at a stride rate of plus 10 percent from preferred, though the results were not significantly different from economy at their preferred stride rate. These results call into question the suggestion that all runners automatically choose the stride that is most optimal for their own body, and suggest that there is a small window within which some amount of stride length optimization via form work could be of benefit. What’s more, form work could benefit a runner both by improving his efficiency and by reducing the forces applied to the major joints of his legs.

One other possibility that Cavanagh mentions in his paper is the idea that his “subjects have adapted through training to the particular combinations of SL (stride length) and SF (stride frequency) which appear to be optimal for their current running styles. It may be that the optimal conditions for an individual can be changed by a period of prolonged training at a stride length which differed considerably from the optimal value.” This is of possible relevance to the effects of footwear on form, especially since shoes can alter such things as stride length and stride frequency. What is still unknown is if or how we adapt over the long term to such changes. For example, if you start running barefoot, you might be quite inefficient at first with a new and unfamiliar combination of stride rate and stride length. However, as time passes and you get used to the new technique, you might find a new optimal combination, and your energy expenditure might end up lower than it was in shoes.

There is one study that puts into practice much of what we have been discussing by investigating if gait retraining can in fact make a runner more efficient. In a 1994 issue of the Journal of Applied Physiology, Don Morgan and colleagues published a study where they identified runners with non-optimal (i.e., inefficient) strides (about 20 percent of their sample of forty-five runners) and attempted to retrain their strides to make them more efficient. At the end of a three week training period, Morgan found that individuals with non-optimal strides who had received stride length training had shifted their freely chosen stride length toward their optimal stride length. Furthermore, energy expenditure at the new freely chosen stride length had decreased markedly—in other words, their new gait after the training period was more efficient than their old gait. Control individuals who did not receive training experienced no such changes.

This study shows that gait retraining does have the potential to shift running gait in positive ways, but they did not look at long term retention of the new gait. Do these people just revert to their old ways after the study is done? Although not geared toward investigating changes in efficiency, recent studies that have provided real-time feedback training to runners with a goal of reducing shock applied to the leg have shown that gait changes can be retained for extended periods after the training period has ceased, so the technique does have promise of lasting benefit. Additional studies like these are needed, and the answers that they provide will help all runners better understand the implications of efforts to modify their stride through form work or changes in footwear.

What About the Rest of the Body?

While much of this book has focused on the running body from the waist down, it’s important to remember that what you do with the parts of the body from the waist up can also influence your running gait. In fact, form problems originating above the waist have the potential to influence both your efficiency and injury risk.

For example, research has suggested that deficiencies in hip flexor mobility can limit the ability of the hip to extend to help drive the body forward as you increase running speed. Your hip flexors (iliopsoas muscle) extend from your vertebrae, sacrum, and pelvis to an attachment on the thigh bone (femur). When the hip flexors contract, they swing the thigh forward and up as occurs when you are marching in place. How does one get tight hip flexors? One hypothesis is that sitting all day keeps the hip flexors in a shortened position, and this can ultimately lead to tightness and reduced mobility of these muscles.

So what do tight hip flexors have to do with running form above the waist? When you try to extend your thigh out behind the body during the late stance phase of the gait cycle (when the foot is preparing to leave the ground), the hip flexors stretch and become taut, thus limiting this extension. Excessively tight hip flexors can magnify this limitation. To compensate for limited extension at the hip joint and still allow the thigh to function to drive the body forward, you tend to instead tilt your pelvis forward, and this can in turn lead to excessive arching of the lower back. The combination of forward tilting of the pelvis and arching of the lower back has been suggested to be linked to both hamstring strains and lower back pain. So, while sitting in an office chair all day may not seem stressful to the body, it might just contribute to a chain of events leading to pain when you run.

In an article published on the UVA Endurosport blog, Jay Dicharry further discusses the influence of posture on running form. Dicharry sees many injured runners who exhibit poor posture when they run. In particular, he emphasizes that many runners tend to arch their lower back. Aside from potential direct effects this might have on the back itself, arching the lower back when you run has the effect of moving the center of mass backward, which in turn can cause the foot to land further in front of the center of mass. The end result is a longer stride. Dicharry suggests that maintaining a more neutral lower back position can help keep the stride shorter and reduce impact. How does one accomplish this? Aside from building a strong core and maintaining limber hip flexors, Dicharry suggests the simple cue to “Run tall!” With a bit of practice, improved posture can go a long way toward helping you iron out kinks in your form.

The arms also play an important role in your running. The primary role of arm swing is to help counterbalance trunk rotation caused by the alternating swing of the legs. Steve Magness, assistant coach to Alberto Salazar at the Nike Oregon Project, describes proper arm swing on his Science of Running blog:

The arm swing occurs from the shoulders, so that the shoulders do not turn or sway. It is a simple pendulum like forward and backward motion without shoulder sway or the crossing of the arms in front of your body. On the forward upswing the arm angle should decrease slightly with the hands in a relaxed fist. On the backswing they should swing back to just above and behind your hip joint for most running speeds. As running speed increases, the arm will swing back more, eventually culminating in going back and upwards in sprinting.

Magness also feels that form problems manifested by the legs can sometimes be linked to problems with arm swing, writing that:

A lot of times we see something happening with the leg that is incorrect and immediately work on fixing the problem by adjusting how that particular leg is working. For example, if an athlete extends out with the lower leg, we immediately try and correct them by having them put their foot down sooner. Instead, the problem seen with the leg could simply be the symptom. The real cause could be in the arm swing. A delayed arm swing or one with a hitch in it causes a delay or hitch in the opposite lower leg. If you watch someone run, the arms and legs are timed up so they work perfectly in synch. If the runner has a problem with their arm swing that causes a delay in the typical forward and backward motion, such as turning it inwards or shoulder rotation, then the opposite leg must compensate for this delay. In many cases, the opposite leg extends outwards as a form of compensation. Therefore, it is important to look at the whole body and understand that the arms and legs are synched together and interact so that a problem in one of them, might simply be a way of compensation.

When Dicharry was asked if he ever looks to the arms for clues when examining an injured runner in his gait clinic, he mentioned that watching movement of the arms can provide “hints” regarding the source of problems that appear in the lower body. For example, he says that “a wide arm swing tells you that there is some type of lateral instability in the lower body, and an arm swing that crosses midline tells you that there is a rotational instability somewhere in the body. You combine that with information you get from doing screening tests and it can help you to track down things like chronic muscle imbalances.”

The lesson here is an easy one to follow: runners tend to spend a disproportionate amount of time worrying about their legs and feet; but lifting their gaze a bit to the upper body can be revealing, and might just help them to identify, and possibly correct, the source of a chronic ache or pain in their lower limbs.

Conclusion

Overstriding has been recognized as a gait flaw for over a century. Science has now provided much-needed backup for the beliefs of running pioneers like Alfred Shrubb and Arthur Newton—excessively long strides decrease a runner’s efficiency by increasing both braking forces and vertical movement of the center of mass, and increase potentially damaging forces applied to the joints.

Although most experienced runners tend to find a stride that minimizes energetic cost, some 20 to 30 percent of experienced runners may not be running at their optimal combination of stride rate and length. To put this in perspective, of the nearly 24,000 runners who completed the 2011 Boston marathon, some 5,000 or more might have been running with a less than optimal stride. The situation for less experienced runners is not as well understood, though some evidence suggests that increasing step rate by 10 percent (and thus reducing stride length) could improve efficiency by a small amount (or at least not incur any metabolic penalty), and also significantly reduce joint loading.

All of this suggests that many runners could benefit by including some amount of stride-shortening form work into their training arsenal. The emerging science on running form change suggests that positive benefits can be accrued via gait retraining (for example, improved efficiency, reduced shock), and that stride changes obtained through gait retraining can be retained as a new normal. Incorporating a bit of barefoot training is one potentially useful approach as barefoot running tends to both shorten strides and reduce impact relative to running in shoes. Incorporating speed work can also be helpful. If you are particularly concerned that an overstriding gait is causing you trouble, attempting a wholesale transition to a more barefoot-style form in your everyday running footwear may be well-worth considering.

If you decide to make an attempt at fine-tuning your gait, it’s important to remember that tinkering with a form element like stride length involves some amount of risk—you don’t want to create a new injury, and it’s better to do nothing than to do harm. John Jerome, in his 1980 book The Sweet Spot in Time, provides some great insight from Peter Cavanagh on this topic. “If you change stride length, you change the action of almost every muscle in the body. A tiny little insignificant, innocent-looking change is really powerful as far as what its consequences are in the muscles of the body.” We are learning how to harness this power, but as yet our understanding is imperfect, and caution is warranted.

In the final analysis, when it comes to form change, many unanswered questions still remain. For now, the wisest and most prudent course of action is to experiment individually, but avoid change for change’s sake. Always remember that any experimentation should be conducted carefully and gradually, and with clear understanding of the relative risks and rewards involved.