Chapter 5

Principle Five

Feel Your Fullness

Listen for the body signals that tell you that you are no longer hungry. Observe the signs that show that you’re comfortably full. Pause in the middle of eating and ask yourself how the food tastes and what your current fullness level is.

It is difficult to identify fullness if you are eating while distracted, stuck in habitual patterns of cleaning your plate, or eating quickly without savoring your food. In the book CrazyBusy (2007), Edward M. Hallowell describes our modern predicament: people are incredibly busy and distracted, thanks to technology that’s always on and a growing sense of urgency that we must be productive at all times. We always have to be doing something. Some people even view sitting down to simply enjoy a meal as a waste of time; they use their mealtimes to get other things done, even if it’s just watching the news.

The activities in this chapter will help you to

- connect with your physical sensations from fullness;

- contemplate how you want to feel, physically, after eating a meal or snack;

- practice identifying the nuances of fullness;

- learn how to say no to people who pressure you to eat when you are either full or not yet hungry; and

- work on the clean-your-plate mentality.

Barriers to Experiencing Fullness

This section describes the many barriers that can make it difficult to hear your body’s signal of fullness, from distracted eating to social pressure to eating past fullness. More importantly, you will practice ways to overcome the obstacles so that you can respond to your fullness signals in a timely manner.

Distracted Eating

Eating while engaged in another activity is much like distracted driving—the driver has the illusion that he or she can drive just fine while texting. Distracted eating is no different (Brunstrom and Mitchell 2006; Robinson et al. 2013). You might have the impression that you are aware of what you are putting in your mouth while reading the news or responding to e-mail. But you are truly missing out on the sensory aspects of eating—the sound of the crunch of lettuce, the cool silkiness of the sour cream next to the thick richness of a bean chili, the scent of cinnamon wafting from your oatmeal, or the visual tapestry of a colorful pasta salad. Although you have the ability to multitask, your mind can truly pay attention to only one thing at a time, like a camera lens. Consequently, if you are preoccupied with doing other activities while eating, not only will your enjoyment of your meal be diminished but also it is likely that you will not sense your fullness until you discover that you are too full and that you ate more than you needed. Or you might discover that you feel full, but because you didn’t experience all the pleasures of your meal, you may still have a profound desire to continue eating to experience those joys.

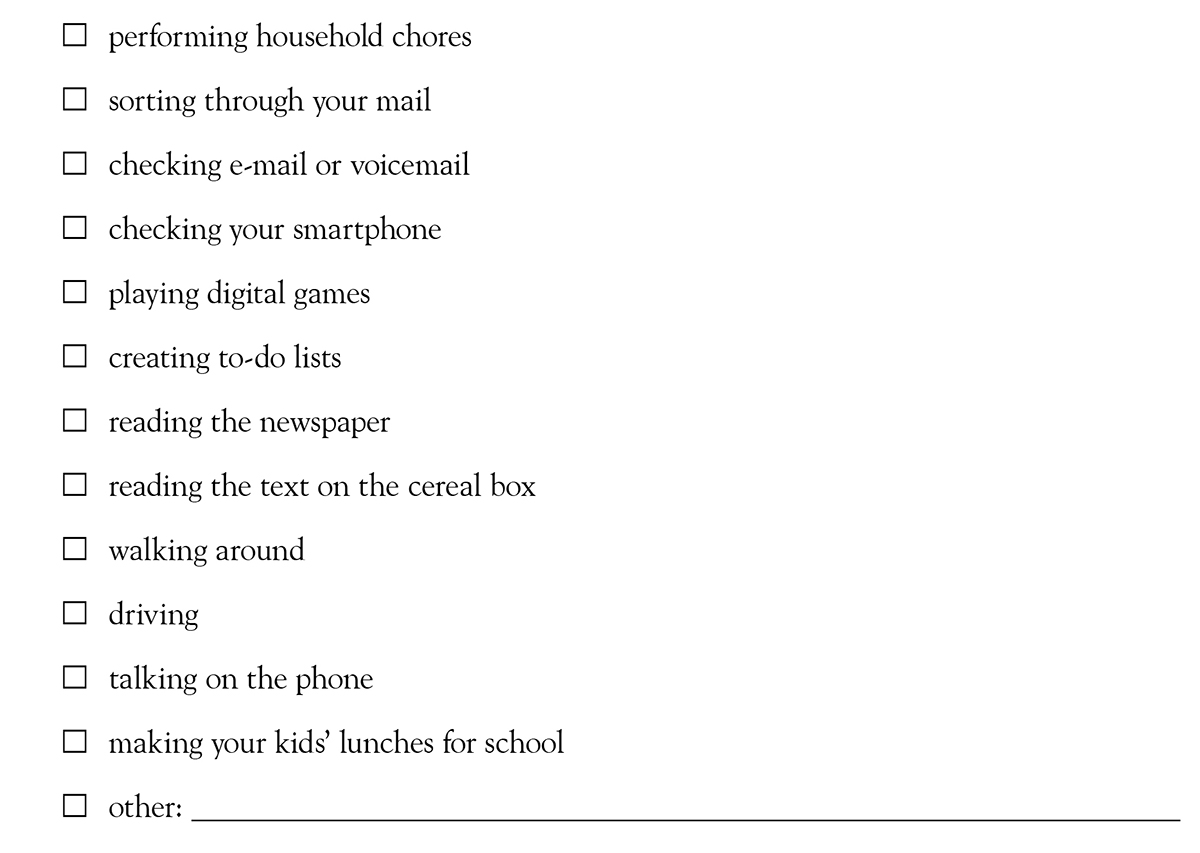

Barriers to Fullness: Eating Without Distraction Self-Assessment

- Place an X next to any of the activities that you frequently engage in while eating:

- Review the items that you checked off, then consider how often you engage in any kind of distracted eating?

- Think back at when you engaged in these activities while eating. In which cases do you remember being noticeably distracted from your food?

- ________________________________________

- ________________________________________

- ________________________________________

- What fears or thoughts of discomfort arise for you (if any), when you think about what it would be like to eat without engaging in any distracting activities?

- ________________________________________

- ________________________________________

- ________________________________________

- What do you need in order to feel ready to eat without distraction? Perhaps you have to ensure that you have enough time, that you have to eat in a room away from your television or computer, or that you have to come to an agreement with family members or roommates about it.

- ________________________________________

- ________________________________________

- ________________________________________

- Optimally, it would be important to avoid any activity that could distract you from the sensual qualities of eating, but that’s usually too big of a step for most people. Describe one step you could take for eating without distraction. For example: I will eat without distraction at several of my dinner meals for one week.

- ________________________________________

- ________________________________________

Eating as Sacred Time: Create the Optimal Eating Environment

Whether you eat alone or with other people, eating is a time to connect with your body and nourish it, especially in regular meals (though the satisfaction and comfort of having a snack should not be seen as inconsequential). If you are with family, friends, or coworkers, it’s also a time to connect with other people. But connection is difficult when there is unwanted distraction. It’s important to create as optimal an eating experience as possible: pleasant, relaxed, and free from distraction. There are two key ways to do this: by setting boundaries and by creating a pleasant environment. Review the statements listed below and place a check by the ideas that you would be willing to try.

Clean Plate Club

Finishing all the food on your plate, regardless of how much is served, is an externally based pattern of eating and a barrier to experiencing fullness, disconnecting you from your internal body cues. Instead, your stopping point is when your plate is empty, regardless of your initial hunger and subsequent fullness level. This type of eating is also common with packages of food—eating until completion, until the package is empty. The familiar parental rule from childhood evolves into a habitual pattern and even an expectation. Other factors can trigger finishing all the food on your plate, including being too hungry, eating too fast, or fear of deprivation.

Clean Plate Assessment

The next set of questions will help you evaluate tendencies to finish all the food on your plate and how to work with this habitual pattern, which does not serve the Intuitive Eating process.

- Read the statements below, and check off the clean plate factors that resonate with you.

- Review the clean plate factors that affect you and answer the following questions:

- Practice Activity. To break the tendency of automatically eating all the food on your plate or from a package, try leaving one or two bites of food uneaten. The purpose of doing this is to break the habit of eating without regard for your satiety level. Practicing this technique will help you to create the pauses that will be needed in order to assess your fullness levels in the upcoming activities.

Automatic Habit Disrupter: Left Hand Eating Experiment

A strong habit like cleaning your plate or eating fast may be insensitive to fullness cues because it is so conditioned and ingrained. But when habit automaticity is disrupted, it’s easier for you to follow through with your intentions, such as leaving food on your plate when you become comfortably full. This next activity offers a novel way to disrupt the autopilot nature of these habits, which will enable you to savor the food and ultimately to be more connected to the physical sensations of emerging fullness.

The following technique is based on a clever study, in which subjects were merely asked to eat with their nondominant hand while watching a movie (Neal et al. 2011). In the first part of the study, the subjects ate with their dominant hand, and they were minimally influenced by their state of hunger or the palatability of the popcorn. (They were given equal amounts of stale and fresh popcorn and didn’t notice the inferior popcorn.) In the second part of the study, the subjects were given a special popcorn box, which was constructed with a vertically aligned handle on one side. To prevent the subjects from using their dominant hand, they were instructed to slide the dominant hand between the handle and the box and hold the box in that manner throughout the movie. The result: less popcorn was eaten, especially if it was stale, because the subjects were more aware of what they were doing; their actions were no longer automatic.

So in the following activity, you will be eating with your nondominant hand (the left hand for most people). This activity is best performed in the privacy of your home. You will need to do something to ensure that you don’t unconsciously begin using your dominant hand, such as strap it to your leg or waist with a belt. You can also simply slip it under your thigh or hold it behind your back while eating, but you will need to stay very aware of it. You should perform this experiment at a meal when you will not be interrupted and when you will have plenty of time to eat.

- the sensations of emerging fullness as you eat, and

- the speed at which you are eating.

After you complete the experiment, answer the following questions:

- How long did it take you to eat your meal? How similar or different was the duration of your meal compared to your usual meals?

- ________________________________________

- ________________________________________

- ________________________________________

- Was it easier to identify the sensations of emerging fullness? At what point during the meal did you begin to experience this?

- ________________________________________

- ________________________________________

- ________________________________________

- What would your eating be like if you were able to eat like this—at this speed and with these same sensations of fullness—when you were using your dominant hand?

- ________________________________________

- ________________________________________

- ________________________________________

Learning to Say No

In social settings, it’s common for people to offer you more to eat. Sometimes a host is just being polite and accommodating, but some individuals gain self-worth from other people eating their food, especially if it is a special recipe. However, it’s important for you to honor your body. It is not your responsibility to make someone happy by eating more food at the expense of your body and comfort. Even if they ask you repeatedly, if you don’t want more to eat, you don’t need to change your answer. Here are some ways you can politely say no to another offer of food. Place a check by the statements that resonate with you.

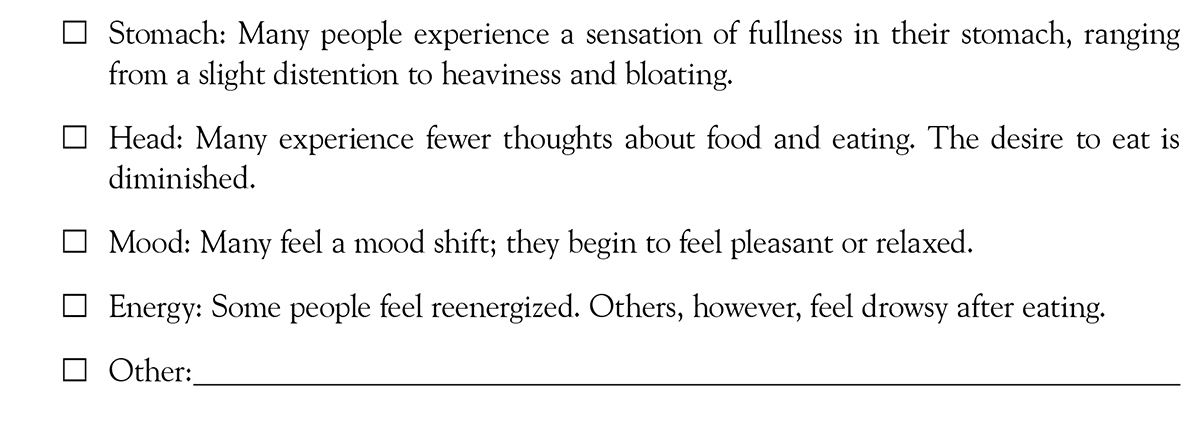

Characteristics of Fullness

There are many ways people experience fullness. Here are some of the different ways that you might experience signs of fullness during and after a meal. Check the statements that apply to you.

The Emergence of Fullness

Some people stop eating when they suddenly feel uncomfortably full. This sudden onset of extreme fullness arises from not paying attention to the emerging sensations of fullness. These sensations are subtle and easy to miss if you do not check in with your body. For many people, this requires slowing down the process of eating. The following activities will help you identify the sensations of fullness.

Interoceptive Awareness with a Water-Drinking Activity

If you have been eating with distraction, it can cultivate a dissociative-like state, in which you are behaviorally eating, but your mind has left your body. Instead of paying attention to the sensations of eating, the mind is paying attention to another activity, such as watching television. In this situation, the emerging sensation of fullness can seem like a mystery unless it is profoundly unpleasant. In chapter 2, Honor Your Hunger, we discussed interoceptive awareness, the ability to perceive the physical sensations that arise within your body. Interoceptive awareness requires your attention.

Research shows that a specific water-drinking activity, called the standardized water load test, can help you identify the sensation of the stomach distension that is commonly associated with fullness (Herbert et al. 2012). It has been shown to be a valid indicator for the perception of fullness in both healthy people and in people with gastrointestinal disorders. This is one way to practice the perception of the physical sensations related to fullness. We want to emphasize the purpose of the activity is to connect to fullness sensations—it is not intended to trick your body into feeling full. (Besides, your body is too smart for that. When tricked into feeling full with a large amount of water, it will eventually recognize the deceit and resume indicating that it needs nourishment.)

Water-Drinking Activity

For this exercise, you will need two to four cups of noncarbonated water, at room temperature, and a five-minute period of time without interruption or distraction. When you are ready, begin drinking the water. There is no need to rush or guzzle the water.

- Notice the physical sensations of swallowing the water and water traveling down your esophagus.

- Don’t stop drinking until you feel the first signs of fullness.

When you have recognized the sensation of fullness, answer the following questions.

- Approximately how much water did you drink? ___________________

- Describe the sensations of swallowing the water and having it travel down your esophagus.

- ________________________________________

- ________________________________________

- ________________________________________

- ________________________________________

- How are these sensations similar to or different from the experience of fullness when eating food?

- ________________________________________

- ________________________________________

- ________________________________________

- ________________________________________

Practice the water-drinking activity as often as you need to in order to become familiar with perceiving the physical sensations associated with fullness.

Factors That Influence Fullness

There are several factors that influence how much food it takes for you to experience comfortable fullness.

- Your Initial Hunger Level. If you start eating when you’re not hungry, there’s no compass for the contrast of fullness, because there’s no hunger to compare it to.

- Unconditional Permission to Eat with Attunement. If you have not made full peace with food (principle 3), then stopping because of fullness may seem like a difficult proposition. It’s hard to stop eating if you believe you will never eat a particular food again.

- Timing. The amount of time that has passed since your last meal or snack will influence your fullness levels. To keep your energy and blood sugar in balance, you generally need to eat every two to six hours.

- Amount of Food. The amount of food that you ate at a prior meal or snack will influence when you become hungry and how much food it will take to reach comfortable fullness.

- Social Influence. Several studies have shown that the presence of people at a meal tends to increase the amount of food you eat. This may be due to distraction, peer pressure, or just simple unawareness.

- Type of Food. The kind of food you eat will influence not only your fullness level but also its staying power. For example, foods with a lot of bulk will make you feel full, but if they are also low in calories, such as vegetables or air-popped popcorn, they will not be satiating. Foods higher in fat, such as avocado, have more sustaining power. The next activity explores this issue in more depth.

Discovering the Fullness and Staying Power of Foods

It’s helpful to be aware of how different types of foods affect your fullness level.

Foods That Increase Fullness

Some types of foods contribute to the feeling of comfortable fullness:

Protein. The protein level in your meals or snacks helps to increase satiety levels. Foods high in protein include meats, beans, poultry, nuts, yogurt, and fish.

Fats. Fats contribute to fullness in two ways. First, the presence of fat in a meal slows down the rate of digestion. Fat is also the slowest part of food to be digested. It plays a significant role in prolonging fullness. Foods high in fats include nuts, salad dressings, oils, butter, nut butters, full-fat dairy products, and avocados.

Carbohydrates. Carbohydrates add bulk, which contributes to satiety. These foods also help to keep a normal blood sugar level, which is essential for providing energy to your cells. Foods high in carbohydrates include pasta, bread, rice, beans, and fruit.

Fiber. Fiber is an indigestible type of carbohydrate, which adds bulk and slows the absorption of carbohydrates into the blood stream. It’s the reason a sandwich made with whole wheat bread may be a little more satisfying than one made with white bread, which has less fiber.

Foods with Little Staying Power

These type of foods temporarily contribute to the feeling of fullness, but it is a short-lived fullness, because they are low-calorie foods. It’s the reason why, for example, you could eat a meal consisting of a big veggie salad (sans dressing and croutons), with a tall glass of unsweetened iced tea, and truly feel full, but then end up hungry only an hour or two later. Or you may have experienced a confusing feeling when eating these foods—you feel physically full, yet still feel like you are missing something. You feel like you are on the prowl, still needing to eat. Our patients often describe it as a restless, food-seeking feeling—they are not satisfied.

High Bulk, Low Calorie. These types of foods are generally vegetables and some fruits.

“Air Foods.” These types of foods are usually familiar to dieters. Air foods fill up your stomach but offer little, if any, energy (calories). They are typically diet foods, such as rice cakes, puffed cereal, and sugar-free beverages.

Artificially Sweetened Foods and Low Carbohydrate Foods. These foods tend to replace carbohydrates with sugar-alcohols and indigestible fibers. These replacements can make you feel temporarily full (and if eaten in excess, they can cause bloating and discomfort). This includes some energy bars, sugar-free gelatin, and low-carbohydrate desserts and snack foods.

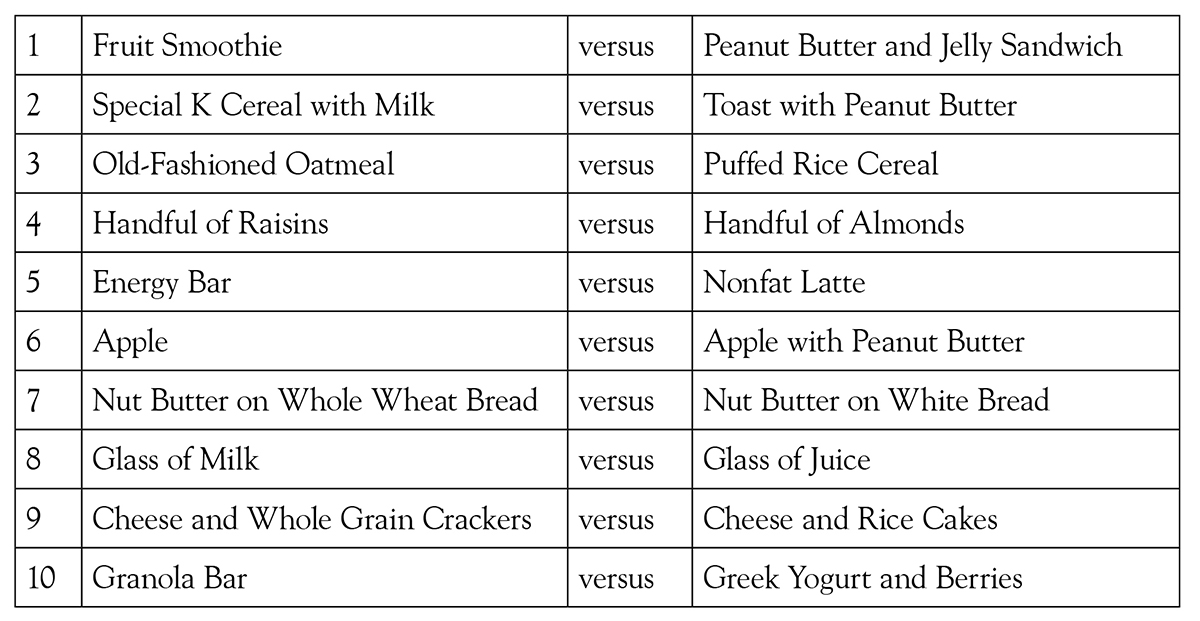

Satiety Snack Practices

In order to experience how different foods affect your fullness level, over the next couple of days, choose at least one of the paired eating experiments below to try out. Be sure to try this at a time when you are experiencing hunger. It would also be best to make your other meals as identical as possible on those days (eating the same things and eating at the same time each day), so a more filling breakfast or a later lunch won’t affect how filling the snack is. Under those controlled conditions, try a fruit smoothie one day and a peanut butter and jelly sandwich the next for comparison.

Snack Satiety Experiment

Jot down the pair of snacks you plan to eat for comparison. Circle the amount of hours that the snack sustained you until you got hungry again.

Reflection

Describe one of the snack experiments you tried. What did you expect to happen?

_____________________________________________

_____________________________________________

Which snack lasted for a longer period of time before you got hungry again?

_____________________________________________

_____________________________________________

Why do you think a particular snack sustained you for a longer period of time?

_____________________________________________

_____________________________________________

How can you apply what you discovered to your snacks for making them more sustainable (if desired)?

_____________________________________________

_____________________________________________

Discovering Meals with Staying Power

Let’s build upon what you have learned about the staying power of snacks and apply it to your meals. In addition to evaluating the sustaining qualities of a meal, you will also be paying attention to how the sensation of fullness wanes after eating a meal.

On the following worksheet, choose a few of your favorite or typical meals over the week to rate. In order to gauge how long the feeling of fullness lasts, you will rate your fullness every thirty minutes, for the two-hour period, after a meal. In the last column, note how long it took until you became hungry again (this could be from one to six hours later).

© 2017 Evelyn Tribole / New Harbinger Publications

Reflection

Review your Getting to Know Fullness Worksheet and then answer the following questions.

What types of meals helped to sustain your fullness level? For how long?

_____________________________________________

_____________________________________________

What types of foods did you eat that did not sustain you for several hours (that is, you were hungry again too soon after the meal)?

_____________________________________________

_____________________________________________

Based on your experiences, describe the components of a meal that would sustain you for several hours.

_____________________________________________

_____________________________________________

Describe the trend of your fullness levels when you checked in every thirty minutes for a two-hour period after a meal.

_____________________________________________

_____________________________________________

Describe any surprises or unexpected experiences with getting to know fullness from meals.

_____________________________________________

_____________________________________________

Fullness Discovery Scale

In order to really get dialed in to the nuances of your fullness, you will need a lot of practice listening for it. Using the Fullness Discovery Scale Journal that follows (and is available for download at http://www.newharbinger.com/26224), keep track of your hunger rating and fullness rating, the quality of the fullness, and the foods eaten for a meal or snack. Do try to be accurate with the time that you ate, as it will help you to see any patterns and trends with your intensity of hunger between meals. Do this for several days. (You may want to make copies of the journal.)

In the journal, first, rate your hunger by circling the number that best reflects your hunger level before your meal or snack. Then begin to eat, but pause in the middle of your snack or meal and gauge (1) the taste of the food, and (2) any sensations of diminishing hunger and emerging fullness. Finally, when you have had enough to eat, rate your fullness level from 0 to 10. Note the quality of your fullness level: is it pleasant, unpleasant, or neutral? In the last column, note if you were doing another activity simultaneously while you were eating (such as reading, surfing the Internet, texting, and so forth).

Reflection on Your Fullness Ratings

Review your satiety ratings and look for trends and patterns. Then answer the following questions.

At which point did you usually feel the sensations of fullness? Perhaps at a 6, perhaps at an 8?

_____________________________________________

_____________________________________________

_____________________________________________

By the time you stopped eating because of fullness, did your fullness experience tend to be pleasant, unpleasant, or neutral?

_____________________________________________

_____________________________________________

What trends did you notice between your hunger and fullness ratings? For example, if you began eating with an unpleasantly hungry rating of a 2 or less, did it take eating more food to experience fullness?

_____________________________________________

_____________________________________________

If you engaged in another activity while eating, what impact did it have on your fullness rating?

_____________________________________________

_____________________________________________

What types of foods did you eat that helped you to become comfortably full?

_____________________________________________

_____________________________________________

Were there any meals in which it took more than the usual amount of food to feel full? If yes, was there any relationship to your initial hunger level or any simultaneous activity you were engaged in?

_____________________________________________

_____________________________________________

The Last Bite Threshold

As you begin to become more familiar with the various sensations of fullness, you will be able to identify the last bite threshold, which is the endpoint of eating (for now). It’s a subtle experience. You become aware that just one more bite of food will likely be your stopping point for a comfortable satiety level. The key element in sensing this threshold is paying attention. On that front, you already have some nice experience under you belt, since you have practiced the fullness exercises in this chapter. For most people, paying enough attention to fullness to sense the last bite threshold will take more practice and patience. There are some specific steps that can help you increase your awareness of the last bite threshold:

- When you finish eating, reflect on how you feel physically. Really check in and notice the sensations of your fullness. Linger with these sensations for a few minutes.

- Next ask yourself, How would I feel if I had stopped a few bites sooner? Note the thoughts that arise. Perhaps you notice a curiosity and desire to explore this idea at your next meal. Maybe that idea is threatening to you. Perhaps the idea makes you sad. That’s okay. Just notice these feelings, without judgment, and jot down your thoughts here:

- ________________________________________

- ________________________________________

- ________________________________________

- ________________________________________

If you feel ready to experiment with stopping at a few bites sooner, move on to the next activity, the Last Bite Threshold Experiment. In order to meaningfully complete this experiment, you need to be at a place where you can recognize general fullness. If you are not at that point yet, that’s okay. It simply means that you need more practice working with the Fullness Discovery Scale Journal. Remember that becoming an Intuitive Eater is not a race, and it is important to work at a pace that feels comfortable for you.

Last Bite Threshold Experiment

Select a meal that will be relaxed and free of distraction.

- Using the techniques described in the instructions for the Fullness Discovery Scale Journal, take a prolonged pause when you are at the point of detecting the absence of hunger and the emergence of fullness (that’s step 2).

- Estimate roughly how many more bites of food it will take to be comfortably full (note that you don’t need to estimate an exact number of bites). And tentatively mark that as your stopping point.

- Continue eating with profound awareness with each bite of food.

- Notice how the food feels in your mouth and tastes.

- After swallowing, notice how your body feels.

- Before taking the next bite of food, ask yourself, is it possible that this next bite is the last bite for me? If your gut sense is yes, plan to stop at that point.

- Notice how you feel. It may be important to remind yourself that you can still eat the rest of this particular food or meal again. Remember there are no forbidden foods.

The more you practice this activity, the more adept you will become at recognizing the last bite threshold. Reflect on your experience.

_____________________________________________

_____________________________________________

_____________________________________________

_____________________________________________

Wrap-Up

In this chapter, you learned different ways to become connected to the sensation of fullness and how to overcome barriers to responding to this cue in a timely and meaningful manner. You discovered a number of factors that affect satiety, including the other people present when you are eating, the time you last ate, the types of foods you are eating, and your initial hunger level. In the next chapter, you will discover the importance of the satisfaction factor in eating, which is the hub of the Intuitive Eating principles.