Chapter 9

Principle Nine

Exercise: Feel the Difference

Forget militant exercise. Just get active and feel the difference. Shift your focus to how it feels to move your body, rather than the calorie-burning effect of exercise. If you focus on how you feel from working out, such as energized, it can make the difference between rolling out of bed for a brisk morning walk or hitting the snooze alarm. If when you wake up, your only goal is to lose weight, it’s usually not a motivating factor in that moment of time.

There is no question that exercise is beneficial for a myriad of health issues from stress reduction to prevention of chronic diseases. The issue for most people is the art of doing it consistently. A big challenge for chronic dieters is choosing the right exercise. If they make their selection based on how many calories they will burn, they might be engaging in activities they don’t necessarily find enjoyable.

When your focus is on an unattainable aesthetic, rather than the intrinsic pleasure of movement, you are setting yourself up for disappointment. Worse yet, exercise becomes part of the dieting mentality and drudgery, which leads to burnout. Consequently, when the dieting stops, so does the physical activity, which is understandable—if your primary experience with exercise has been connected with dieting or when you’re not eating enough food, you won’t learn that exercise can feel good.

Note that we use the term exercise interchangeably with movement and physical activity. The World Health Organization emphasizes that physical activity does not mean only exercise or sports (2010). In fact, these endeavors are subcategories of physical activity, which includes other activities as well, such as playing, gardening, doing household chores, dancing, and recreational activities.

There are two critical components to physical activity and health—less time sitting every day and more time engaging in physical activity itself. A growing body of research shows that sitting too much is not the same thing as exercising too little (Henson et al. 2016; Cheval, Sarrazin, and Pelletier 2014; Craft et al. 2012). Studies show that even if you exercise regularly, it does not protect you from the effects of sitting too much. In this chapter, we explore both of these issues.

In this chapter, you will

- discover physical activities that you enjoy;

- explore the qualities of mindful exercise, while paying attention to the connection with your body;

- identify personal benefits and reasons to exercise;

- discover how to break through exercise barriers; and

- learn how to increase activity by sitting less.

Start By Simply Sitting Less in Your Daily Living

A person can now eat, work, shop, bank, and socialize without having to leave the comfort of their chair.

—Henson et al. 2016

Thanks to technology and urbanization, the average person spends more time sitting than sleeping (Craft et al. 2012). This lifestyle of prolonged sitting is now recognized as a unique health hazard, which increases the risk of chronic diseases, especially heart disease and type 2 diabetes (Henson et al. 2016). When the body sits for long period of time—an hour or more—there is a physiological stasis effect; your metabolic health comes to a standstill.

That’s why it is not enough to focus on exercise guidelines (which are still important and will be described later). Studies show that many people who exercise regularly still sit too much and are actually considered to be sedentary. You can be sedentary at work, at school, at home, when travelling, or during leisure time by

- sitting or lying down while watching television or playing video games;

- sitting while driving a car, or while travelling by plane, train, or bus; and

- sitting or lying down to read, study, write, or work at a desk or computer.

Consequently, public health programs are aiming to find ways both to reduce total sitting time and to increase the number of breaks in prolonged sedentary periods—all without the need to break a sweat. Just to be clear, this is not about hopping out of your chair to perform a set of jumping jacks. Rather, it’s about simply getting up and breaking the stillness of sitting, which could be as easy as getting up to talk on the phone and continuing the conversation while standing. These types of activities are classified as Non-Exercise Activity Thermogenesis (NEAT) (Cheval, Sarrazin, and Pelletier 2014). They include a wide range of low-intensity behaviors: the ordinary activities of daily living, fidgeting, spontaneous muscle contraction, and maintaining proper posture. Don’t underestimate the important role these seemingly mundane activities play in metabolic and cardiovascular health! Even the most incidental tasks of everyday living, like taking out the trash, offer significant health benefits (Rezende et al. 2016).

If you are out of shape, starting with an effort focused on less sitting (or NEAT) is a much less daunting endeavor than beginning with a new fitness regime.

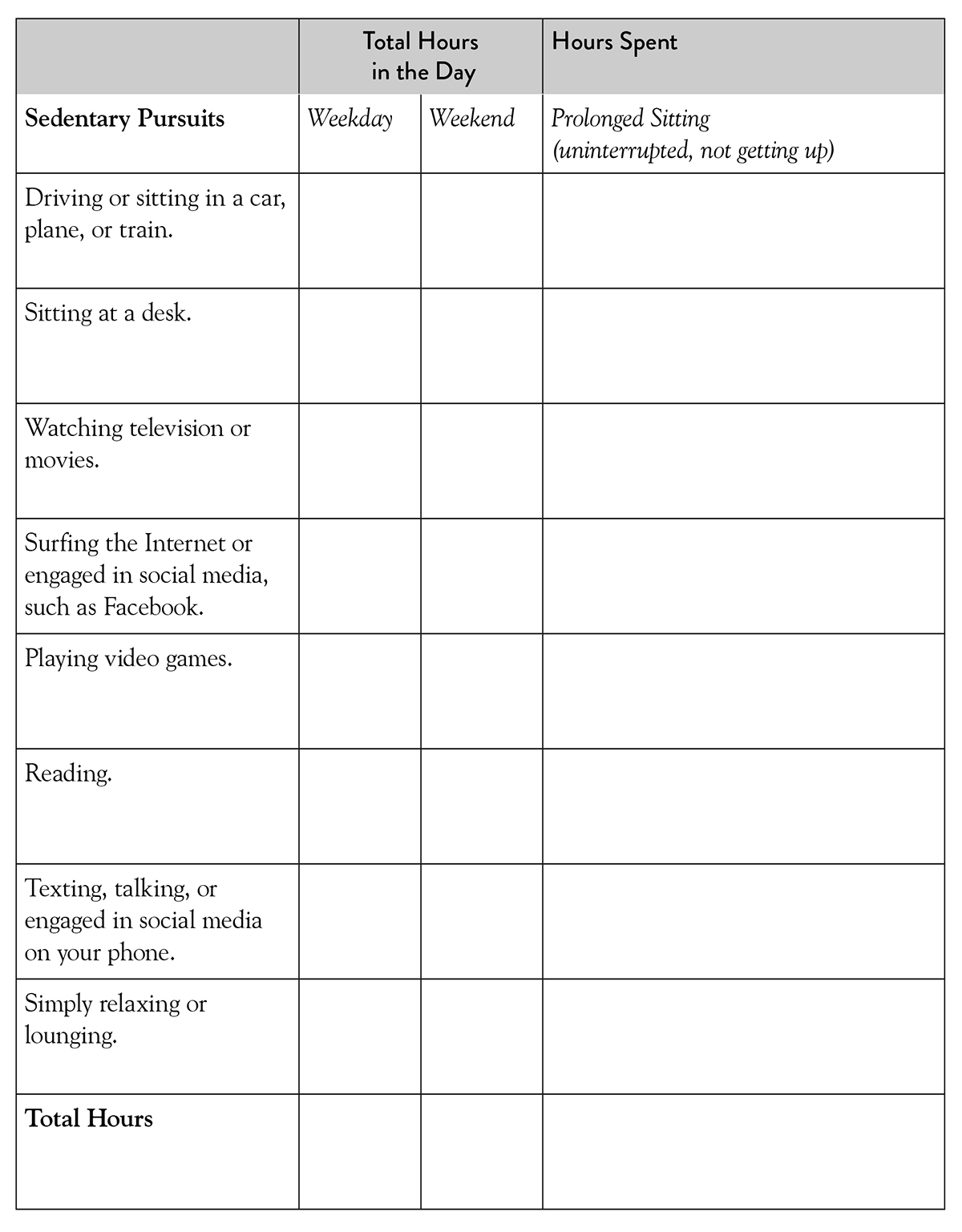

Getting Real: Estimating the Amount of Your Sitting Time

We spend so much time chasing deadlines and running errands that it is easy to perceive that we are living active, rather than sedentary, lifestyles. But for most people, this chase is accomplished while sitting in a car or behind a desk or staring at a smartphone.

First, let’s get an idea of what your sitting lifestyle is really like (without judgment, please). The purpose is to provide a better picture of how much time you spend sitting, which will give you a better idea of where it might be feasible to make some easy changes. Select two typical days (one weekday and one day on the weekend). On the following chart, track the hours you spend sitting on those days, and in the right-hand column, note the longest uninterrupted period of time spent sitting. If you sat continuously to watch a three-hour movie, you would write down “three hours”—but if you got up to go to the kitchen halfway through the movie, your entry would be “one and a half hours.”

Exploring How to Sit Less and Interrupt Prolonged Sitting

After you complete your estimated time spent sitting during the weekdays and weekends, answer the following questions.

How many hours do you spend sitting or lying down during

- weekdays ________

- weekends ________

What was your longest bout of uninterrupted sitting, and is this typical for you?

_____________________________________________

_____________________________________________

Below is a list of ways to interrupt sitting. Read through them and place a checkmark next to those that you would be willing to incorporate into your everyday living.

The Pursuit of Pleasurable Activities

A growing body of research shows that deriving pleasure from physical activities may be one of the most important factors for sustaining consistent exercise, rather than focusing on the classic fitness prescriptions of frequency, intensity, and duration (Parfitt, Evans, and Eston 2012; Ekkekakis, Parfitt, and Petruzzello 2012; Petruzzello 2012; Segar, Eccles, and Richardson 2011). This concept of engaging in activities that you enjoy or that give you increased energy or an improved mood is based on the Hedonic Theory of Motivation. This theory basically says that people will repeat activities that feel good. Conversely, activities that cause pain or discomfort will wane or be avoided. This is welcome research, refuting the popular notion that people need to be bullied into physical activity in the name of health.

All too often, people have been cajoled to disregard the cautionary messages of the body with adages such as suck it up or no pain, no gain. This can lead to a big disconnect, because it encourages pain and minimizes the messages you are receiving from your body. Just as dieting teaches you to ignore what your body wants and needs, these old patterns of exercise only separate you from the wisdom of your body. Remember, only you can possibly know how your body feels.

Let Your Body Be Your Guide: Mindful Exercise

Paying attention to how your body feels during and after movement is an important way to discover enjoyable activities. Mindful exercise places value on paying attention to how your body feels—without judgment, comparison, or competition. It is an activity that fosters attunement, which includes four components (Calogero and Pedrotty 2007):

- It rejuvenates, rather than exhausts or depletes.

- It enhances the mind-body connection.

- It alleviates stress, rather than amplifies stress.

- It provides genuine enjoyment and pleasure.

The more you can tune in to your body’s sensations during physical activities (not merely thinking about the sensations, but actually feeling them), the more it can help you cultivate interoceptive awareness (your perception of the physical sensations from within your body). During exercise, these sensations can include the intensity and rate of your breathing, speed and strength of your heartbeat, muscle tension and muscle relaxation, and overall perceived effort or exertion. The more you listen to your body, the more it heightens your ability to “hear” it, which will also increase your interoceptive awareness in other areas—like perceiving hunger and fullness. Think of it as a form of cross-training for your mind-body connection—all of which are connected and interdependent.

Exploring How the Pursuit of Enjoyable Activities Would Impact You

- How would pursuing physical activities for pleasure and enjoyment affect your

- desire to be active?

- ________________________________________

- ________________________________________

- ________________________________________

- selection of type of activity you engage in, especially if you feel out of shape?

- ________________________________________

- ________________________________________

- ________________________________________

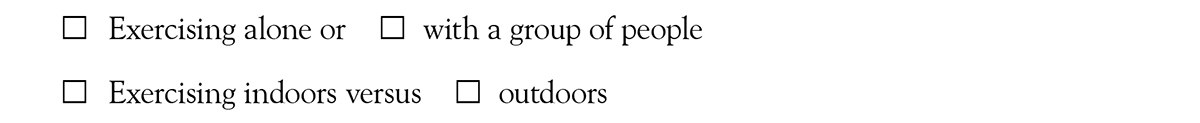

- selection of the environment where you exercise—with others or alone, in public or private, outdoors or in a gym?

- ________________________________________

- ________________________________________

- ________________________________________

- How would a pleasant physical activity feel to you, during and after you exercise?

- How would placing an emphasis on activities that are invigorating, rather than exhausting or depleting, affect your choice and frequency of exercise?

Benefits of and Barriers to Physical Activity

Benefits of Physical Activity

While most people know there are many health benefits gained from exercise, it is such a generalized idea that it may lose its specific relevance to you. In this section, we briefly review the benefits of physical activity in two parts: reducing the risk of diseases and improving life-enhancing qualities.

Health Benefits of Physical Activity

Review the following chart of the health benefits of physical activity. In the first section, Reduces Health Risks, put a checkmark in the box next to any diseases and conditions that are in your family history (parents, grandparents, and siblings). In the next section, Improves Quality of Life, circle the benefits that are meaningful to you.

Exploring the Short-Term Life-Enhancing Benefits of Physical Activity

In this section, we will focus on the more noticeable short-term benefits of exercise, the things that generally make you feel good. Using the information from the chart above, answer the following questions.

Describe two short-term benefits of exercise that are appealing to you.

_____________________________________________

_____________________________________________

How would selecting an activity based on benefits that you actually feel, such as improved energy, mood, strength, or sleep, affect your day-to-day quality of life? For example, consider how feeling more energized after an activity would affect you for the rest of the day (or night).

_____________________________________________

_____________________________________________

_____________________________________________

_____________________________________________

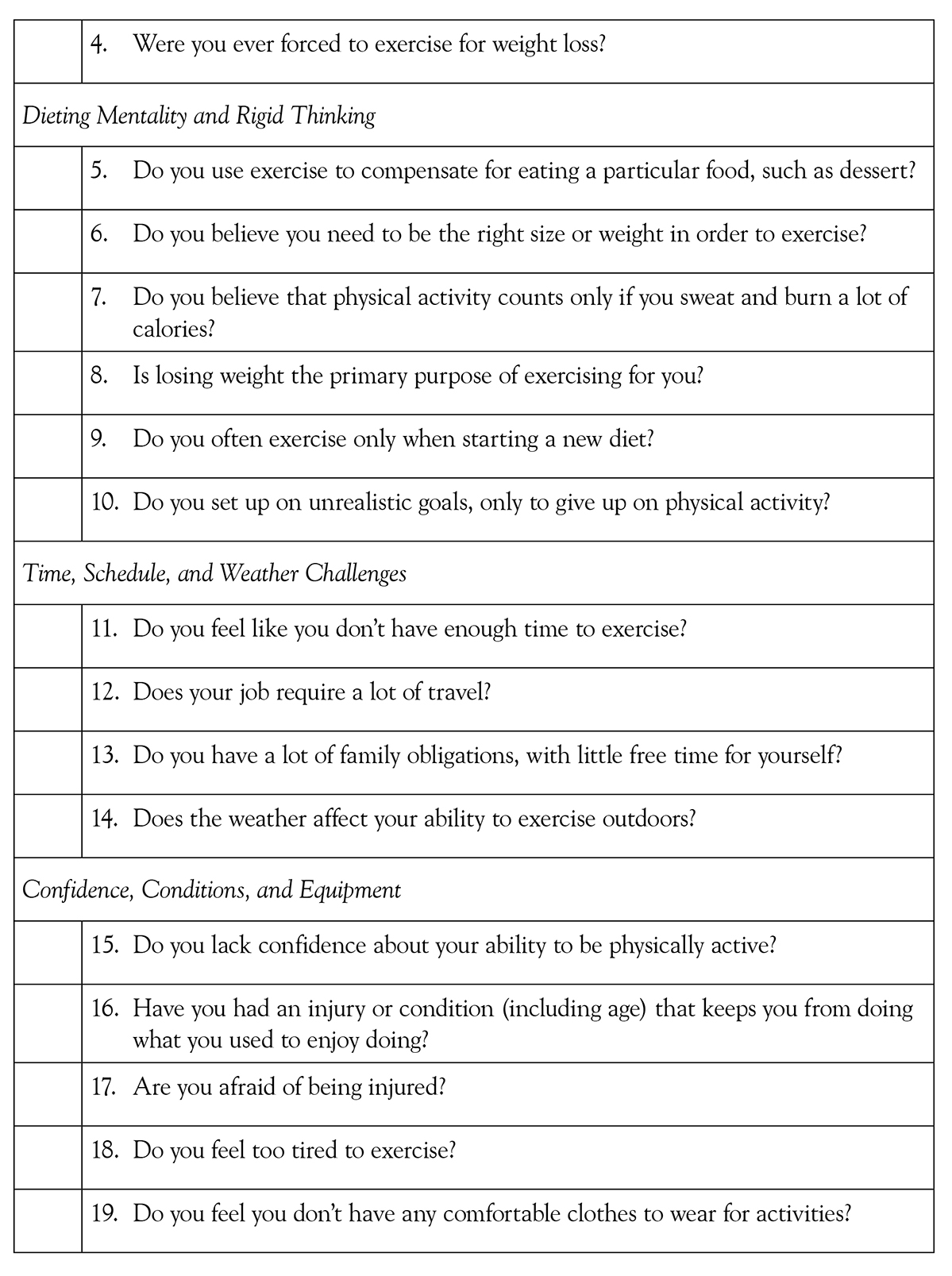

Barriers to Exercise

Despite the well-known health benefits of physical activity, inactivity is a growing problem globally. According to the World Health Organization (2010), inactivity is the fourth leading cause of death—with approximately 3.2 million deaths each year attributable to insufficient physical activity.

Even when you personally value the benefits of exercise and have a genuine desire to be active, there can be obstacles to overcome—some of which may be based on how you experienced play time or sports growing up. Perhaps you were teased or bullied into exercising, which can create a disdain for any activity. Or there may be present-day challenges, such as a demanding schedule with school, kids, work, or a combination thereof. Understanding your barriers to exercise and creating strategies to overcome them can help you make physical activity a regular part of your life.

Evaluating Barriers to Exercise

Review the questions and check the ones that apply to your situation.

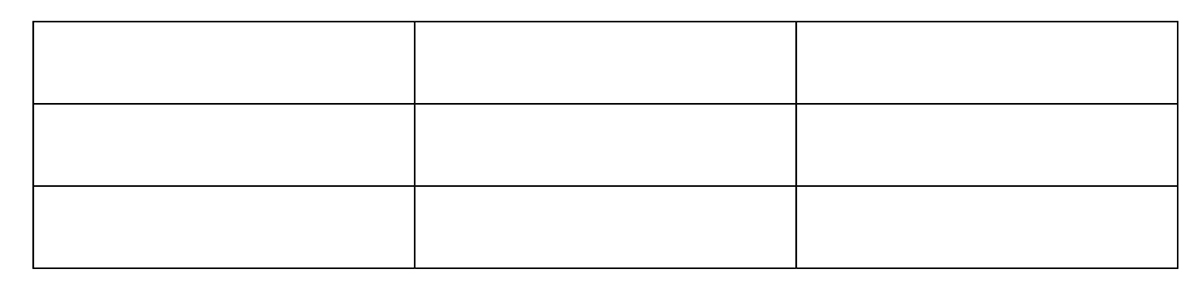

Exploring Barriers to Exercise

Select the barriers that present the biggest obstacles to physical activity for you. Describe what you could do to overcome each barrier.

First Barrier:

_____________________________________________

_____________________________________________

Solution:

_____________________________________________

_____________________________________________

_____________________________________________

Second Barrier:

_____________________________________________

_____________________________________________

Solution:

_____________________________________________

_____________________________________________

_____________________________________________

What do you need in order to make physical activity a nonnegotiable priority in your life? Consider how you are doing in self-care and setting boundaries.

_____________________________________________

_____________________________________________

_____________________________________________

_____________________________________________

Overcoming Barriers: Importance of a Body-Positive Environment

If you do not feel comfortable exploring a new activity or fitness endeavor alone, seeking a qualified personal trainer or a gym that has guided group activities can be helpful. Yet far too many people feel out of place at a gym; they don’t feel welcome. Worse yet, some gyms and classes are focused on weight loss rather than enjoyment, strength, and energy.

Fortunately, there is a growing recognition on the importance of body positivity within the fitness industry, evidenced by the Body Positive Fitness Alliance (BPFA). The BPFA requires affiliated members and corporations to be trained in and to comply with their seven pillars of body-positive fitness in order to make physical activity more accessible, approachable, and fun. In addition, it promotes an effective community, with exercise professionals who work within their scope of practice and are focused on full health and body positivity. We think the pillars are revolutionary and suggest that people look for these qualities in a fitness environment or trainer.

The Body Positive Fitness Alliance Seven Pillars1

- Accessibility. I choose to provide an environment where anyone from any walk of life can step foot in and move their bodies without worrying about what they look like while doing it.

- Approachability. I choose to eliminate any intimidating elements from this space, which I provide. I understand the difference between intimidating and challenging.

- Enjoyment. I apply the fact that people are motivated when they feel like they belong to a community where they can become their best selves and can have fun!

- Community. I have built a community free of egos and full of heart. I have taught my members that “fit” does not have a look. Anyone who walks in our doors is a member of our family. We celebrate each other’s successes, we lift each other up when down, and we don’t stand for judgment.

- Scope of Practice. I agree that being a fitness professional does not necessarily make one a nutrition professional, a mental health professional or a general health advisor. I refer my clients to appropriate care when their needs are outside of my scope of practice. I can identify and I value evidence-based science. Studied and proven methods drive my practice.

- Full Health. I live in the belief that health is equal parts mental, physical and emotional. Balance is the key to health and one third cannot thrive if another third is suffering.

- Body Positivity. I believe in praise and celebration of what one can do and not what one looks like. I understand the damage which is done to individuals when they are encouraged to take up less space. I empathize with the fact that individuals are unique in shape and size, and one’s shape or size does not necessarily indicate their strength, endurance, and overall fitness and health. I understand that happiness does not rely on smallness and fitness does not have a “look.”

Discover Physical Activities You Enjoy

In this section you will explore physical activities to try, learn the optimal frequency and duration of exercise, and monitor how your body feels, with the emphasis on enjoyment, of course!

Getting Started

To help you get started with making physical activity an enjoyable part of your life, consider these factors.

- What are your preferences?

- What is your current fitness level?

- ________________________________________

- Considering your current fitness level, what would be the most pleasurable type of activities to explore?

- ________________________________________

- ________________________________________

- How do you want to feel after physical activity? Perhaps calm or perhaps energized?

- ________________________________________

- ________________________________________

Physical Activities Worksheet

Review this list of physical activities. The five middle columns indicate different aspects of the activities—whether the activity is typically practiced as a game, whether it is a solo or group exercise (or both), and whether it’s done indoors or outdoors (or both). In the right-hand column, rate your interest in exploring each exercise from 0 to 10, with 0 being not interested and 10 being very interested.

Exploring Physical Activities

- List the activities that you gave a rating of 7 or higher for your interest in exploring. Then circle the top three activities that you would like to try. (Note that if none of the activities was appealing enough to get a rating of 7 or above, list some activities that you might tolerate.)

- What do you need in order to get started? Consider your schedule, comfortable clothing, comfortable shoes, equipment, and a check-up from your doctor.

- What do you need in order to keep your expectations realistic, especially if you are not fit or if you are trying a new activity, especially one that requires practice to develop the new skills?

- ________________________________________

- ________________________________________

- ________________________________________

- ________________________________________

- ________________________________________

How Much Activity and How Often?

Doing some physical activity is better than doing none.

—World Health Organization

In this section, we will explore how much activity to strive for in a week, but as you read, it is important that you keep in mind the World Health Organization’s advice: any activity is better than none. When it comes to accruing the health benefits of physical activity, even just short bouts of ten minutes will benefit your cardiovascular health (World Health Organization 2010). Please don’t use the recommended exercise targets discussed below to be beat yourself up if you currently don’t meet the guidelines. It is important to start with where you are at and what is comfortable for you.

How Many Minutes Per Week?

Both the WHO and the Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans recommend the following targets for adults aged eighteen to sixty-four years.

- Aim for seventy-five to 150 minutes of physical activity per week, depending on whether the intensity of the activity is moderate or vigorous (see the next section for details).

- Be sure to include at least two muscle-strengthening activities a week as part of your total time spent in physical activity. (Examples of these types of activities include some types of yoga and lifting weights.)

If you are sixty-five years old or older, the guidelines are the same as above, with an added recommendation for those who have poor mobility: engage in activities that enhance balance and prevent falls at least three days per week.

Effort or Intensity

Generally, intensity refers to how much effort you put forth in an activity, which can vary from person to person. One way to gauge this effort is using an exertion scale of 0 to 10, where sitting is 0 and the greatest effort possible is 10.

Moderate-intensity activity requires a medium level of effort, about a 5 or 6 on the exertion scale. This effort produces a noticeable increase in your breathing rate and heart rate. Examples of these types of activities include general gardening and walking. Aim for 150 minutes of these types of activities.

Vigorous activity is about a 7 or 8 on this scale, produces a large increase in your breathing and heart rate, and often causes sweating. Examples include tennis, jogging, and hiking on hilly terrain. If you engage in these types of activities, aim for at least seventy-five minutes throughout the week.

A general rule of thumb is that two minutes of moderate-intensity activity counts the same as one minute of vigorous-intensity activity (USDHHS 2008), so thirty minutes of moderate-intensity activity is roughly the same as fifteen minutes of vigorous activity.

Physical Activity Planning Guide

When you start to explore what getting seventy-five to 150 minutes of exercise in a week looks like, it can seem surprisingly manageable. Consider your regular obligations, and use the weekly planning grid below to indicate when and how much activity is realistic for you.

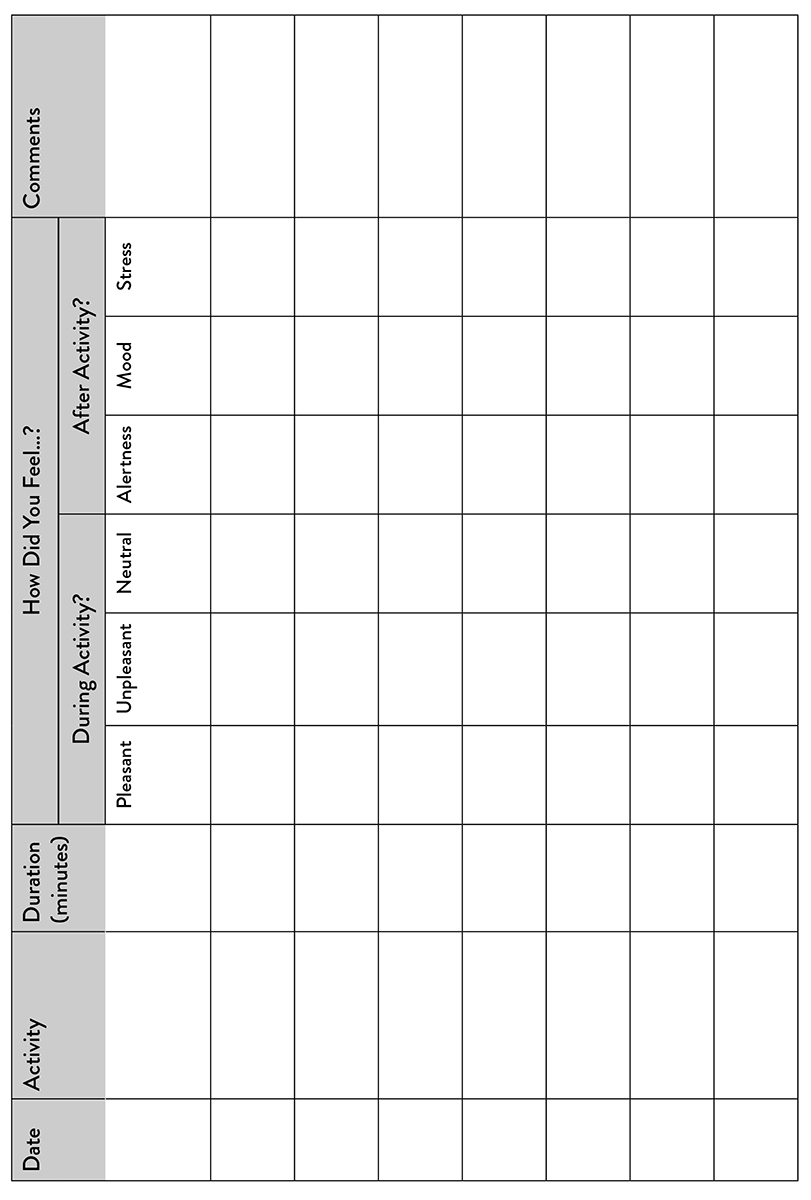

Monitoring How You Feel

It’s important to pay attention to how you feel during and after your activity—this will help you prevent injuries, while helping you focus on the sensation of pleasantness during activity and the accruing benefits of movement (such as improved mood and alertness). The following journal is a useful tool to monitor these factors. In the columns on the left, record the date, your activity, and its duration. In the central columns, note how you feel during and after the activity. During your activity, pay attention to the intensity of your breathing, the sensations of your muscles (such as relaxed, tense, or sore), and your overall perceived effort of exertion—then reflect on whether the activity felt pleasant, unpleasant, or neutral. After the exercise, reflect on the less directly physical effects of your activity—did it improve your alertness, mood, or stress levels? Some of these effects you might feel immediately, some later, and these effects may last a long time or be brief. In the right-hand column, make any other comments you would like about the activity.

Reflection of Activity Journal

After you complete a few days of this journal, review it and answer the following questions.

During your activity, how does your perceived effort and the intensity of your breathing affect the pleasantness of your overall experience?

_____________________________________________

_____________________________________________

_____________________________________________

What is the difference between the sensation of feeling invigorated versus feeling exhausted and depleted from an activity?

_____________________________________________

_____________________________________________

_____________________________________________

If your activity felt unpleasant, what could you do to improve your enjoyment? Consider the intensity of your effort, your expectations, and whether you were competitive with yourself or others. Also consider other factors, such as getting enough sleep the night before, how frequently you engage in the activity, and the environment in which your activity took place.

_____________________________________________

_____________________________________________

_____________________________________________

After your activity, what trends did you notice about your overall mood, alertness, and stress level?

_____________________________________________

_____________________________________________

Did you notice any other benefits, such as being more eager to take on the day or any improved quality of your sleep?

_____________________________________________

_____________________________________________

In the beginning, you might not notice any trends of improved overall well-being. Keep in mind that it takes about twelve weeks to get a physiological effect from moving your body consistently.

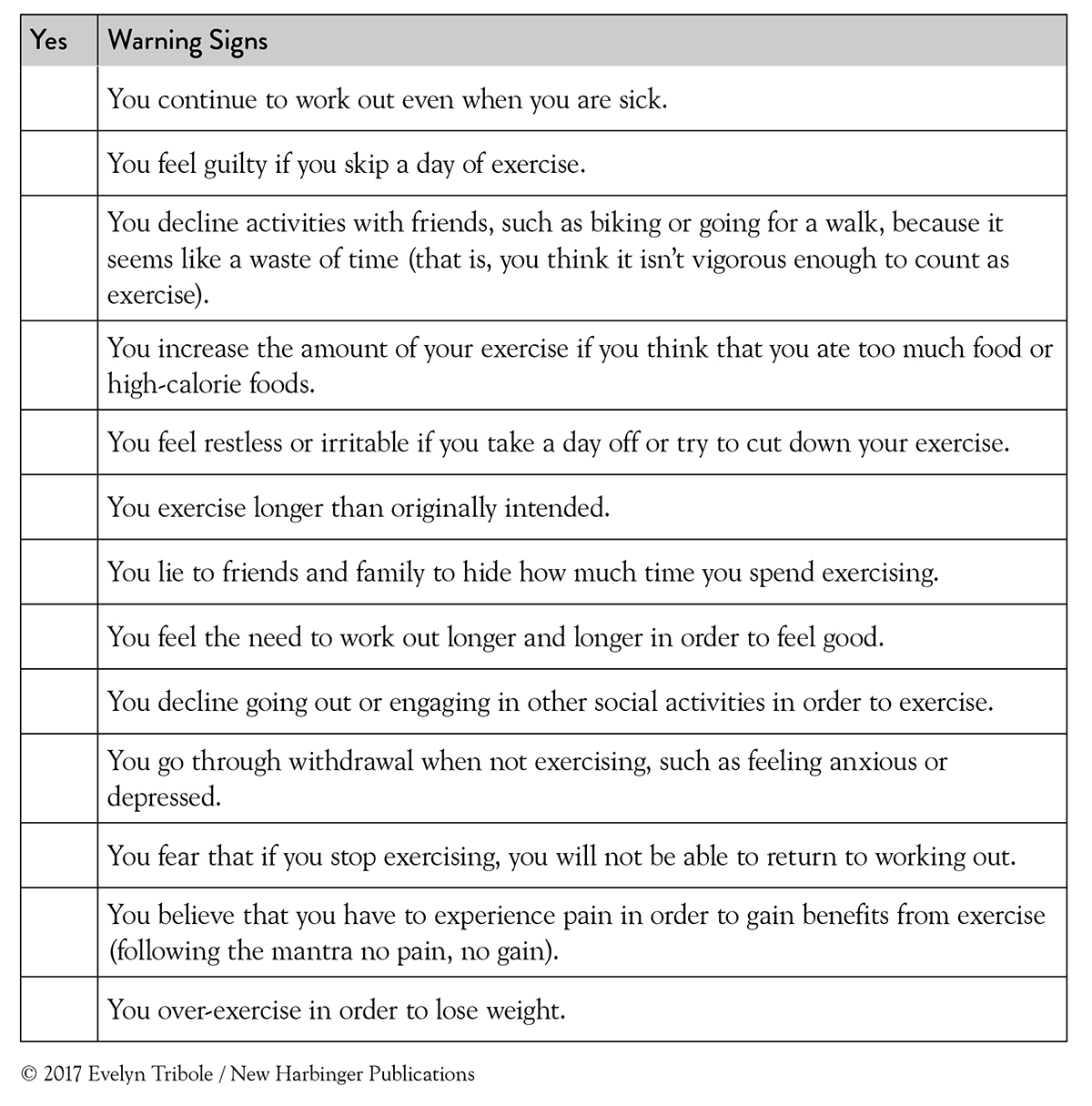

Exercising Too Much

We have spent most of this chapter on how to overcome too little physical activity, but it’s important to recognize if you have crossed over the line into an unhealthy pursuit of compulsive exercise, which could also be a sign of an eating disorder. The table below lists some warning signs to consider. Check yes to the statements that apply to you.

If you find that you are exercising too much, it’s important to listen to your body rather than the exercise rules from your mind. This may mean taking some time off from working out and letting your body recover. Keep in mind that you do not get out of shape from missing a few workouts, but you could get sick or injured if you don’t take a break. The process of recovering from over-exercise is similar to recovering from the diet mentality. You might need to see an eating disorder specialist.

Wrap-Up

Although it is important to move your body regularly and refrain from prolonged sitting, it is very important to listen to your body. This might mean taking time off if you are sick, injured, or sleep deprived. That’s okay—it will keep you healthy and more likely to engage consistently in physical activity, which is important in the big picture of your lifetime.