5

In assuming that Texas had a government Houston was, in a broad sense, correct.

While he had been delaying his urgent march to rescue the blind widow, the Convention at Washington received its first intimation of the fall of the Alamo in a guarded letter from the Commander himself. Next day Houston confirmed the disaster, and deserters from Gonzales embroidered the horror. Part of the Convention fled without ceremony. Other members got drunk. Chairman Ellis attempted to adjourn the sittings to Nacogdoches, but a well-knit delegate with a stubby beard stood on a bench and told the members to return to their work.

THE RETREAT FROM GONZALES 233

The Constitution was slapped together at ten o'clock that night. At midnight the Convention elected the well-knit delegate provisional president of the Republic.

His name was David G. Burnet. Thirty years before he had deserted a high stool in a New York counting house to see the world. He was with Miranda's romantic but rash descents upon Venezuela. He had roamed with the wild Indians in the little-explored West. One bulge in his close-fitting coat was made by a Bible, another by a pistol; and he did not drink or swear.

Lorenzo de Zavala was chosen vice-president.

Burnet's Cabinet was elected on the spot. At four in the morning of March seventeenth the new Administration was sworn in, and the Convention took a recess for breakfast.

After the meal a remnant of the members came together again. "An invaded, unarmed, unprovided country," wrote Colonel Gray, the useful diarist, "without an army to oppose invaders, and without money to raise one, now presents itself to their hitherto besotted and blinded minds and the awful cry has been heard from the midst of their Assembly, 'What shall we do to be saved?' " When a fugitive dashed into town shouting the groundless rumor that Santa Anna's cavalry had crossed the Colorado, the question of salvation became a matter too intimate for parliamentary procedure. "The members are now dispersing in all directions. A general panic seems to have seized them. Their families are exposed and defenseless, and thousands are moving off to the east. A constant stream of women and children and some men, with wagons, carts and pack mules are rushing across the Brazos night and day."

Mr. Burnet called a Cabinet meeting, at which it was decided to transfer the capital of the Republic "to Harrisburg on the Buffalo Bayou, as a place of more safety than this." The removal began in the rain on the following day. Vice-President Zavala rode a small mule. At his side Johnathan Ikin, an English capitalist, slopped through the mud on foot, revolving in his mind some doubts concerning a proposed five-million-

dollar loan. Mrs. Robinson, the wife of the late Lieutenant-Governor, also walked. Some one had stolen her horse.

Mrs. Harris, widow of the founder of the new capital, entertained the dignitaries of the government. Secretary of War Thomas J. Rusk and Colonel Gray dried themselves before her fire and rolled up in a blanket on the floor. The Secretary of Navy and the Attorney-General did the same. But the President, the Vice-President and the Secretary of State had a bed. Lorenzo de Zavala, Jr., embraced his father and, attended by a French valet, breasted the rainswept stream of fleeing humanity to join Sam Houston's Army.

6

The flight of the government did not diminish the difficulties of the Commander-in-Chief. "It was a poor compliment to me," he wrote to Rusk, "to suppose that I would not advise the convention of any necessity that might arise for their removal. . . . You know I am not easily depressed but, before my God, since we parted I have found the darkest hours of my life! . . . For forty-eight hours I have not eaten an ounce, nor have I slept." During the retreat "I was in constant apprehension of a rout . . . yet I managed as well, or such was my good luck," that the army was "kept together. At Gonzales "if I could have had a moment to start an express in advance of the deserters ... all would have been well, and all at peace" east of the Colorado. But the deserters "went first, and, being panic-struck ... all who saw them breathed the poison and fled." 8

Next day the outlook brightened. "My force will [soon] be highly respectable. . . . You will hear from us. ... I am writing in the open air. I have no tent. . . . Do devise some plan to send back the rascals who have gone from the army. . . . Oh, why did the cabinet leave Washington? . . . Oh, curse the consternation that has seized the people." 9

Matters continued to improve. Houston's determination to

THE RETREAT FROM GONZALES 235

fight brought a tide of recruits, until ultimately he had perhaps fourteen hundred men—poorly equipped, without artillery, but eager for battle. Houston maneuvered down the river, and the alert Deaf Smith captured a Mexican scout who revealed that General Sesma was approaching with seven hundred and twenty-five infantry and two field pieces. Sesma camped on the west side of the river two miles above the right wing of Houston's army, and sent for reinforcements. Lieutenant-Colonel Sidney Sherman, a dashing Kentucky volunteer with the best-looking uniform in camp, begged to cross and attack, but Houston refused.

For five days the armies faced each other in expectation of battle. There were a few brushes between patrols. On the evening of March twenty-fifth a Gonzales refugee named Peter Kerr galloped into camp shouting that Fannin had surrendered after a bloody defeat. The cry went up to fall upon Sesma at once. Houston seized Kerr and denounced his story. Sesma would be taken care of in good time. The soldiery went to bed and during the night General Sesma was heavily reinforced.

The only music in the Texan camp was tattoo and reveille beaten on a drum by the Commander-in-Chief himself, who had learned the art under Captain Cusack of the Mounted Gunmen in Tennessee. Each night between these calls, General Houston inspected the lines of sentinels, conferred with his staff, wrote dispatches and turned the pages of the Commentaries of Caesar and Gulliver's Travels, which he had brought in his saddle-bags from Washington to read in his spare time.

There was an occasional hour for a talk with George Hockley. A fast comradeship grew between the General and his aide. They were old acquaintances and had come near fighting a duel in Nashville ten years before. But these mellow midnight conversations while his army slept carried Sam Houston back to days more remote. He spoke of his mother, of the consolation her teachings had been to his troubled life and of his will to reestablish himself as a mark of respect for her memory.

Reveille was beaten an hour before dawn, when the camp

stood to arms until full day outlined the west bank of the river where Mexican patrols lurked in the brush. After breakfast the Commander-in-Chief would kick off his boots and sleep for three hours. By mid-forenoon he was on his round of inspection, which carried him to every precinct of the camp. Since joining the troops at Gonzales the Commander had used liquor sparingly, if at all, but carried a small vial of salts of hartshorn which he periodically dabbed to his nostrils.

The morning after the Fannin alarm Houston did not sleep. The soldiers saw their General sunning himself on a pile of saddles while he cut chews of tobacco with a clasp knife and studied a map. The rumor spread that the General was planning a battle, and there was a great cleaning of rifles and clattering of accouterments. Noon came and Houston had not begun his inspections. Something was in the wind. By mid-afternoon the atmosphere was tense when an order came to break camp, load the wagons and be ready to retreat at sunset.

The army was dumfounded. What did it mean?' Detachment commanders went flying to headquarters to ascertain. They were told to return to their companies and carry out orders. The army would march at sunset as directed.

Bewildered and complaining, the army left fires alight and picked its way eastward through the tall grass. Seventy-five families were encamped on the river, hoping for a battle. They fled. "Among these was my own," one soldier wrote. "I now left the army and with the families set out on the retreat." 10 Many of Houston's soldiers did likewise.

Six miles from the river the army bivouaced without fires and grumbled itself to sleep. The first light of morning saw the column pressing on. Staff officers rode up and down. "Close up, men. Close up." Major Ben Fort Smith of the staff asked Captain Moseley Baker what he thought of the movement. Captain Baker replied in a loud voice. He thought little enough of the movement, and unless reasons for the retreat acceptable to the Army were forthcoming, Sam Houston would be deposed from command before the day was over.

THE RETREAT FROM GONZALES 237

The march was so relentlessly pressed that Captain Baker did not find an opportunity to carry out his plan. That night, with thirty weary miles behind them, the men were too tired to care. They had covered the whole distance between the Colorado and the Rio de los Brazos de Dios and were bivouaced a mile from San Felipe de Austin. But sentiment against the retreat had grown, and after a few hurried interviews Captain Baker turned in, confident that the Army would throw off Houston's leadership in the morning. 3

CHAPTER XIX The Plain of St. Hyacinth

Reveille rolled in the darkness, and stiff men, casting grotesque shadows, fumbled about the breakfast fires. A bleak wind blew ashes in the coffee kettles. The Commander-in-Chief did not show himself, but after breakfast the punctual staff officers bounced through camp with brisk orders to form companies for the march.

Soldiers grumble as a matter of form, but those ably led acquire a habit of obedience that overbears many weaknesses of the flesh. The companies fell in, and only Captains Moseley Baker and Wily Martin sustained the bold resolutions of the night before. Lieutenant-Colonel Sherman sent Houston an announcement of their refusal to march. This brought Hockley at a gallop, shouting to Sherman to put the column in motion. "If subordinates refuse to obey orders the sooner the fact is ascertained the better!" The column moved, but the companies of Baker and Martin stood fast.

A furious rain caught the column toiling through a swamp up the west bank of the River of the Arms of God. Wagons stalled and men floundered in the mud. The sheer force of the downpour broke the ranks. The exertions of all the staff officers and of Houston himself were unable to preserve an appearance of military order. Stragglers began to grope back toward Baker and Martin. Houston paused under a tree, penciling an order to Baker to take post in defense of the river

THE PLAIN OF ST. HYACINTH 239

crossing at San Felipe, and Martin at Fort Bend. They complied.

For three terrible days Houston drove the stumbling column through the unrelenting rain, advancing only eighteen miles. On March 31,1836, he halted in a "bottom" by the Brazos with nine hundred demoralized and mutinous men remaining of the thirteen hundred he had led from the Colorado five days before. Near by glowed the lights of Jared Groce's house, where in 1829 took place the first discussion on Texas soil to solicit Sam Houston to assist the fortunes of the restless province.

The country was in worse temper than the Army. Houston's abandonment of the Colorado gave fresh wings to the terror that had been calmed somewhat by his halt and the expectation of a battle. A fierce outcry broke from government and populace, which took little account of the strategic handicap Fannin's capitulation had imposed upon their General. Although students of the military science, viewing the campaign in retrospect, entertain divided opinions on the matter, Houston believed that a victory on the Colorado would have been indecisive and a reverse irreparable. General Santa Anna believed that the elimination of Fannin had made all Texas untenable for Houston, and arranged for an early return to Mexico City.

During the retreat came the paralyzing intelligence that Fannin and three hundred and ninety men had been executed in cold blood after surrendering, and of the massacre of a smaller band under Captain King. General Santa Anna was keeping his word. Texas shuddered and fled. Mr. Burnet's government lost its grip and the flight of the population became a hysterical plunge toward the Sabine.

Sam Houston's rain-soaked and rebellious mob was the Republic's solitary hope—menaced by four Mexican columns sweeping forward to enclose its front, flanks and rear. The profound wisdom of hindsight suggests that had the Commander given some explanation of his retreat, Army and country might have fared better. But the inscrutable Indian

brain of The Raven had divulged nothing and explained nothing. "I consulted none;" he wrote in the saddle, "held no councils of war. If / err, the blame is mine" 1 And he had taken no notice of criticism.

The story grew that Houston meant to abandon Texas in a mad effort to induce United States troops on the Sabine to take up the war. That first wet night in the Brazos Bottoms, Houston wrote Secretary of War Rusk for news of the government's program, if any. "I must let the camp know something ... [so that] I can keep them together." 2

2

Sam Houston promised his mob a glorious victory and drove a parcel of beeves into camp for a barbecue. Then he began to remold the rabble into an army to receive the enemy, providentially delayed by the rains.

The Bottoms quaked with activity, and no trick in the repertory of the professionally trained soldier was neglected. Drills, inspections, maneuvers; maneuvers, inspections, drills. Units were revamped, two new regiments created, a corps d'elite of Regulars formed. Anson Jones was so dizzily yanked from infantry private to regimental surgeon that he complained of "having to do duty in both capacities" for several days. Discipline and esprit de corps began to return. Recruits came in. Scouts watched the encroaching enemy. Patrols watched the camp. Jackals caught plundering refugees were assisted out of their troubles at the nearest tree.

Encouraging reports from the United States were published to the Army. Wharton wrote to Houston from Nashville: "Your name . . . [will] raise 5000 volunteers in Tennessee alone. . . . Especially the Ladies are enthusiastic. . . . The Ladies have pledged themselves to arm equip & entirely outfit 200 volunteers now forming." 8 The lovely Nashville ladies! Miss Anna Hanna stitched a flag for her old beau. A woman in black on a river plantation flaunted, like a banner, her proud glance in the face of hostile family frowns.

THE PLAIN OF ST. HYACINTH 241

Houston's difficulties were staggering. Burnet was an enemy. He had a spy on Houston's staff. The Commander-in-Chief intercepted one of this creature's letters, declaring that after abandoning the use of liquor Houston had taken up opium. A newly promoted major returned from Moseley Baker's outpost and began to sound out officers on a scheme to "beat for volunteers" to proclaim a successor to General Houston. Sidney Sherman—a full colonel now, his uniform the brightest sight in camp—was to be the man.

An Indian uprising threatened the refugees. Mexican agents were undoing the peace-work Houston had accomplished after leaving Refugio. "My friend Col Bowl," Houston wrote the war lord of the Cherokees, "I am very busy, and will only say how da do, to you!" The salutation took the form of a reminder that Houston had been the red man's friend and that the red man would find it to his profit to reciprocate. "My best compliments to my sister, and tell her that I have not wore out the mockasins which she made me."*

On April seventh Santa Anna reached San Felipe. Houston reinforced Baker, and for four days the Mexican artillery tried to force a crossing without success, although an American named Johnson, serving with the Mexicans, caused some discomfort by firing across the flooded river with a rifle. With this cannonade rumbling in his ears, Houston received a brief message from President Burnet. "Sir: The enemy are laughing you to scorn. You must fight." 5 The camp was in a frenzy of excitement. Leaders of the contemplated mutiny believed their hour had struck, but changed their minds when Sam Houston had two graves dug and affixed to trees about camp a memorandum saying that the first man to beat for volunteers would be shot. 6

Word that Santa Anna had abruptly abandoned his attempt to cross at San Felipe found Houston in a buoyant mood. He had just received his long awaited guns—two iron six-

pounders, the gift of friends in Cincinnati. Clad in a worn leather jacket, he was watching the camp blacksmith cut up old horseshoes for artillery ammunition, when a young soldier said that the lock on his rifle would not work. "All right, son," said General Houston, "set her down and call around in an hour." The boy came back, stammering an apology. He was a recruit, he said, and did not know that the man pointed out to him as a blacksmith was the Commander-in-Chief. "My friend, he told you right. I am a very good blacksmith," replied Houston taking up the gun and snapping the lock. "She is in order now." 7

The next two days Houston devoted to moving his army across the Brazos, while Santa Anna crossed near Fort Bend. The Texans encamped on the premises of a well-to-do settler named Donahoe, who demanded that Houston stop the men from cutting his timber for fire-wood. General Houston reprimanded the wood-gatherers. Under no circumstances, he said, should they lay ax to another of Citizen Donahoe's trees. Could they not see that Citizen Donahoe's rail fence would afford the fuel required? That night the army gallants scraped up an acquaintance with some girls in a refugee camp, turned Mr. Donahoe out of house and held a dance. 8

When the army left Donahoe's at dawn Moseley Baker demanded to know whether Houston intended to intercept Santa Anna at Harrisburg or to retreat to the Sabine. The General declined to answer. Seventeen miles from Donahoe's the road forked, the left branch leading to Nacogdoches and the Sabine, the right branch to Harrisburg. If Houston should attempt to take the left road, Captain Baker proclaimed that he would "then and there be deposed from command." 9 Rain slowed the march, however, and only by borrowing draft oxen from Mrs. Mann of a refugee band that followed the army, did the troops by nightfall reach Sam McCurley's, a mile short of the crossroads.

Next morning a torrential rain failed to extinguish the excitement in the ranks. Which road would Houston take?

THE PLAIN OF ST. HYACINTH 243

The menacing Baker thundered warnings, but the Sabine route had its partizans among the troops. All of the refugees favored it. The Commander-in-Chief treated the commotion as if it did not exist and without comment sent the advance-guard over the Harrisburg Road.

A wail arose from the refugees. There was a halt and a wrangle which Houston terminated by ordering Wily Martin to escort the refugees and watch for Indian hostilities to the eastward. The Commander-in-Chief thought this cleared the path for his pursuit of Santa Anna, but he had reckoned without Mrs. Mann. She demanded the return of her oxen. Wagon Master Rohrer, a giant in buckskin with a voice like a bull, brushed the protest aside as too trivial for the attention of a man of affairs, and cracking his long whip, addressed the oxen in the sparkling idiom of the trail. Whereupon, Mrs. Mann produced from beneath her apron a pistol, and, if rightly overheard, addressed Mr. Rohrer in terms equally exhilarating. General Houston arrived in time to compose the difficulty with his usual courtly deference to the wishes of a lady.

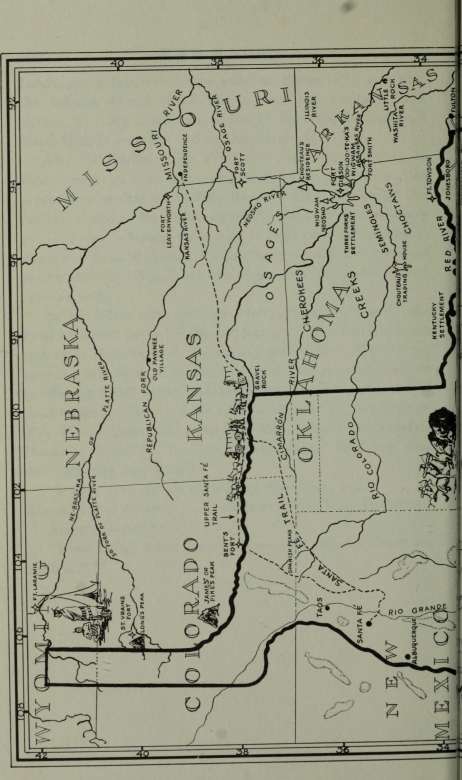

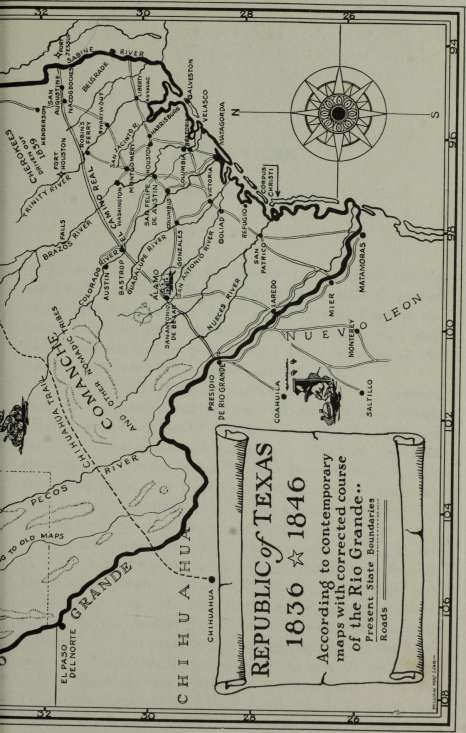

Three or four hundred men followed Martin, or departed independently, leaving Houston with less than a thousand to follow Santa Anna who rode with a magnificent suite at the head of a picked force of veterans. But Santa Anna was now the pursued and Houston the pursuer. General Santa Anna commanded the center of three armies. The rains, however, had fought on Houston's side, and there was a chance that by fast marching he might catch the Mexican Commander-in-Chief out of reach of his cooperating columns. Another factor in Houston's favor was the Sabine retreat story. Houston had never intended to fall back to the Sabine, but the report was so persistently circulated and never denied that the Mexicans included it in their strategic calculations.

Over the boggy prairie path, by courtesy the Harrisburg Road, Houston drove the little column fearfully. Nothing delayed the advance. Wagons were carried over quagmires on the backs of the men. The greatest trial was the guns. In

camp the enthusiastic soldiers had christened them the "Twin Sisters," but now they thought of other names.

On the morning of April eighteenth the army reached the Buffalo Bayou, opposite Harrisburg, having covered fifty-five miles in two and a half days. Mounts and men were dead beat. Houston had never been in this part of the country before. He spent his nights in constant touch with the scouts and in the study of a crude map, covered with cabalistic pencil-ings of his own.

The army rested. Harrisburg was in ashes; Santa Anna had come and gone. Deaf 10 Smith swam the bayou and toward evening returned with two prisoners, a Mexican scout and a courier. The courier's saddle-bag bore the name of W. B. Travis—souvenir of the Alamo. It contained useful information. Santa Anna had dashed upon Harrisburg with eight hundred troops in an effort to capture President Burnet leaving Cos to follow. But the raid netted only three printers who had stuck to their cases in the office of Gail Borden's Texas Telegraph, Editor Borden and the government had fled to Galveston Island in the nick of time, with Santa Anna racing in futile pursuit to take them before they left the mainland. On his soiled map Houston traced the situation of his quarry, not ten miles away, groping among the unfamiliar marshes that indented Galveston Bay and the estuary of a certain nebulous Rio San Jacinto. 11 Sending his army to bed the Commander-in-Chief continued to pore over the chart. Two hours before dawn he slept a little.

After the daybreak stand-to General Houston delivered a speech. The "ascending eloquence and earnestness" put one impressionable young soldier in mind of "the halo encircling the brow of our Savior." "Victory is certain!" Sam Houston said. "Trust in God and fear not! And remember the Alamo! Remember the Alamo!"

"Remember the Alamo!" the ranks roared back. They had a battle-cry.

There was just time for a short letter to Anna Raguet's

THE PLAIN OF ST. HYACINTH 245

father: "This morning we are in preparation to meet Santa Anna. . . . It is wisdom growing out of necessity." 12

The pick of the army advanced, leaving the sick and the wagons with a rear-guard. After a swift march Houston made a perilous crossing of Buffalo Bayou, using the floor torn from a cabin as a raft. The column hid in a woods until dark, and then advanced warily, encircled by the scouts under Deaf Smith and Henry Karnes. At a narrow bridge over a stream—Vince's bridge over Vince's Bayou, men who knew the country said—the column trampled the cold ashes of Santa Anna's camp-fires. The night was black and the advance painfully slow. Equipment had been muffled so as to make no sound. A low-spoken order passed from rank to rank to be ready on the instant to attack. Rifles were clutched a little closer. One mile, two miles beyond the bridge, down a steep ravine and stealthily up the other side crept the column.

At two o'clock in the morning the word came to break ranks. In the damp grass the men dropped beside their arms. With the salt of the sea in their nostrils they slept for an hour; then formed up and stumbled on until daybreak, when their General concealed them in a patch of timber.

Some of the Vince brothers' cows were grazing in this wood. The army had a commissary! Throats were noiselessly cut and General Houston had given permission to build fires when a party of scouts dashed up. They had driven off a Mexican patrol and learned that Santa Anna was on the road to Lynch's Ferry. The butchers were called from their delectable task and the fires pulled apart. The men fell in to the banging of muskets and the clank of ramrods as old charges were fired and fresh ones sent home. The breakfastless army headed for Lynch's Ferry, three miles eastward. Santa Anna approached the ferry from the south, with five miles to go.

From the crest of a grass-grown slope Houston's army got its first view of Lynch's Ferry, lying at the tip of a point of lowland where Buffalo Bayou flowed into the San Jacinto lliver. On the farther side of the river was a scattering of

unpainted houses—the town of Lynchburg. Behind the town bulged a round hill, the side of which was covered with people who gazed for a moment at the column filing down the slope, and then melted away. They were Texas Tories waiting to pilot Santa Anna toward the Sabine.

Having the choice of positions, Houston established himself in a wood of great oak trees, curtained with Spanish moss, that skirted the bayou just above its junction with the San Jacinto. He posted the infantry and cavalry in order of battle within the thick shelter, and placed the Twin Sisters on the edge of the trees so as to command the swelling savannah that lay in front of the woods. This semi-tropical prairie extended to the front for nearly a mile, thick with waving green grass, half as high as wheat. A woods bounded the prairie on the left, screening a treacherous swamp that bordered the San Jacinto. Swamp and river swung to the right, half enclosing the prairie and giving it a background of green a tone darker than the active young grass. Over this prairie Santa Anna must pass to gain the ferry.

The Texans were prepared to fight, but the presence of cows in the grass revealed the force of Napoleon's famous maxim. Again the fires crackled, and this time steaks were sizzling on the spits when the scouts came galloping across the plain. They said that Santa Anna was advancing just beyond a rise. The Twin Sisters were wheeled out a little piece on the prairie. The infantry line crept to the edge of the woods.

Santa Anna's bugles blared beyond the swell. A dotted line of skirmishers bobbed into view, and behind it marched parallel columns of infantry and of cavalry with slender lances gleaming. Between the columns Santa Anna advanced a gun. The skirmishers parted to let the clattering artillerymen through.

The Twin Sisters were primed and loaded with broken horseshoes. General Houston, on a great white stallion, rode up and down the front of his infantry. Under partial cover of a clump of trees, three hundred yards from the Texan lines, the Mexican gun wheeled into position.

THE PLAIN OF ST. HYACINTH 247

Joe Neill, commanding the Twin Sisters, gave the word for one gun to fire. Crash, went the first shot by Sam Houston's artillery in the war. There had been no powder for practise rounds. Through the ragged smoke the Texans could see Mexican horses down and men working frantically at their piece. Their Captain had been wounded and the gun carriage disabled.

Crash! The second Twin cut loose, and the Mexican gun replied. Its shot tore through the branches of the trees above the Texans' heads, causing a shower of twigs.

Rat-tat! The Mexican skirmishers opened fire and plumes of black dirt jumped in front of the Texas infantry. A ball glanced from a metal trimming on General Houston's bridle. Colonel Neill dropped with a broken hip.

The Texan infantrymen had held their beads on the dotted line for so long that their faces ached. Every dot was covered by ten rifles, for no Texan had to be told that when he shot to shoot at something. A row of flaming orange jets rushed from the woods and expired in air; the dotted gray line sagged into the grass and did not reappear.

The Twin Sisters whanged away and the Mexican gun barked back, but the state of its carriage made accurate aim impossible. Santa Anna decided not to bring on a general engagement, and sent a detachment of dragoons to haul off the crippled gun. Dashing Sidney Sherman begged to take the cavalry and capture the Mexican field piece, and finally Houston consented. Sherman lost two men and several horses, but failed to get the gun. General Houston gave him a dressing down that should have withered the leaves on the trees. A private by the conquering name of Mirabeau Buonaparte Lamar who had borne himself courageously was promoted to command the cavalry regiment, numbering fifty-three.

Sherman was considerable of a camp hero just the same; he and Deaf Smith who had captured the ferry-boat loaded with Mexican flour. Dough, rolled on sticks and baked by the fire, made the postponed meal notable, after which the men

spread blankets by the fires and talked themselves to sleep over the big fight that was to take place in the morning. Less than a mile away, under the watchful eyes of Houston's scouts, flickered the camp-fires of the enemy.

On the twenty-first of April, 1836, reveille rolled at the usual hour of four, but a strange hand tapped the drum. The Commander-in-Chief was asleep, with a coil of rope under his head. He had left instructions not to be disturbed. It was evident that the anticipated dawn attack would not take place. The ranks silently stood to until daylight, precisely as they had done every other morning, except that the Commander-in-Chief slept through it all. Nor did the soldier hum of breakfast-time arouse him. It was full day when Sam Houston opened his eyes—after his first sleep of more than three hours in six weeks. He lay on his back, studying the sky. An eagle wheeled before the flawless blue. The Commander-in-Chief sprang to his feet. "The sun of Austerlitz," he said, "has risen again." 13

An eagle over the Cumberland on that awful April night— an eagle over the muddier Rubicon—an eagle above the plain of St. Hyacinth. Did these symbolic birds exist, or were they simply reflections of a mind drenched with Indian lore? The eagle was Sam Houston's medicine animal. When profoundly moved it was from the Indian part of his being and not the white-man part that unbidden prayers ascended.

The camp was in a fidget to attack. It could not fathom a commander who sauntered aimlessly under the trees in the sheer enjoyment, he said, of a good night's sleep. Deaf Smith rode up and dismounted. The lines of the old plainsman's leathery face were deep. His short square frame moved with a heavy tread. The scout was very weary. Night and day he and Henry Karnes had been the eyes of the army, and considering the tax of the other faculties that deafness imposed

THE PLAIN OF ST. HYACINTH 249

upon a scout, the achievements of Smith elude rational explanation.

"Santa Anna is getting reinforcements," he said in his high-pitched voice. And surely enough, a line of pack-mules was just visible beyond the swell in the prairie. "They've just come over our track. I'm going to tell the general he ought to burn Vince's bridge before any more come up."

After a talk with Smith, Houston told his commissary general, John Forbes, to find two sharp axes, and then strolled past a gathering of soldiers remarking that it wasn't often Deaf Smith could be fooled by a trick like that—Santa Anna marching men around and around to make it look like a reinforcement. Smith returned from another gallop on to the prairie. "The general was right," he announced loudly. "It's all a humbug." But privately he informed Houston that the reinforcement numbered five hundred and forty men under Cos, which raised Santa Anna's force to the neighborhood of thirteen hundred and fifty. Houston's strength was slightly above eight hundred. 1 *

Houston later told Santa Anna that his reason for waiting for Cos was to avoid making "two bites of one cherry." But he did not care to see Filisola, who might turn up at any time with two or three thousand Mexicans. Handing the axes to Smith, Houston told him to destroy Vince's bridge. "And come back like eagles, or you will be too late for the day."

Unaware of these preparations, the camp was working itself into a state. To all appearance the General was wasting good time, and jealous officers were only too eager to place this construction on the situation. At noon John A. Wharton, the Adjutant-General, with whom the Commander-in-Chief was not on the most cordial terms, went from mess to mess, stirring up the men. "Boys, there is no other word to-day, but fight, fight!" Moseley Baker harangued his company. They must neither give nor ask quarter, he said. Resting on his saddle horn, Houston narrowly observed the Baker proceedings. He rode on to a mess that Wharton had just addressed. Every

one was boiling for a fight. "All right," observed the General. 'Tight and be damned." 15

Houston called a council of war—the first and last, but one, of his career. The question he proposed was, "Shall we attack the enemy or await his attack upon us?" There was a sharp division of ideas. Houston expressed no opinion, and when the others had wrangled themselves into a thorough disagreement he dismissed the council.

At three-thirty o'clock, the Commander-in-Chief abruptly formed his army for attack. At four o'clock he lifted his sword. A drum and fife raised the air of a love-song, Come to the Bower, and the last army of the Republic moved from the woods and slowly up the sloping plain of San Jacinto. The left of the line was covered by the swamp, the right by the Twin Sisters, Millard's forty-eight Regulars and Lamar's fifty cavalry. A company from Newport, Kentucky, displayed a white silk flag, embroidered with an amateurish figure of Liberty. (The Lone Star emblem was a later creation.) A glove of the First Lieutenant's sweetheart bobbed from the staff. On the big white stallion Sam Houston rode up and down the front.

"Hold your fire, men. Hold your fire. Hold your fire."

The mastery of a continent was in contention between the champions of two civilizations—racial rivals and hereditary enemies, so divergent in idea and method that suggeston of compromise was an affront. On an obscure meadow of bright grass, nursed by a watercourse named on hardly any map, wet steel would decide which civilization should prevail on these shores and which submit in the clash of men and symbols impending— the conquistador and the frontiersman, the Inquisition and the Magna Charta, the rosary and the rifle.

For ten of the longest minutes that a man ever lives, the single line poked through the grass. In front lay a barricade

THE PLAIN OF ST. HYACINTH 251

of Mexican pack-saddles and camp impedimenta, inert in the oblique rays of the sun.

"Hold your fire, men. Hold your fire."

Behind the Mexican line a bugle rang. A sketchy string of orange dots glowed from the pack-saddles and a ragged rattle of musketry roused up a scolding swarm of birds from the trees on the Texans' left. A few Texans raised their rifles and let go at the dots.

"Hold your fire! God damn you, hold your fire !" 16 General Houston spurred the white stallion to a gallop.

The orange dots continued to wink and die. The white stallion fell. Throwing himself upon a cavalryman's pony, Houston resumed his patrol of the line.

"Fight for your lives ! Vince's bridge has been cut down!" It was Deaf Smith on a lathered mustang. Rather inaccurately, the soldiers understood Vince's bridge to be their sole avenue of retreat.

Twenty yards from the works, Houston made a signal with his hat. A blast of horseshoes from the Twin Sisters laid a section of the fragile breastwork flat. The infantrymen roared a volley and lunged forward drawing their hunting knives. "Remember the Alamo ! Remember the Alamo !"

They swept over the torn barricade as if it had not been there. Shouts and yells and the pounding of hoofs smote their ears. Through key-holes in a pungent wall of smoke they saw gray-clad little figures, with chin-straps awry, running back, kneeling and firing, and running back—toward some tents where greater masses of men were veering this way and that. The Texans pursued them. The pungent wall melted; the firing was not so heavy now as the Texans were using their knives and the bayonets of Mexican guns. The surprise lacked nothing. Santa Anna had thought Houston would not, could not, attack. In his carpeted marquee, he was enjoying a siesta when a drowsy sentinel on the barricade descried the Texan advance. Cos's men were sleeping off the fatigue of their night march. Cavalrymen were riding bareback to and from

water. Others were cooking and cutting wood. Arms were stacked.

When the barrier was overrun a general of brigade rallied a handful of men about a field piece; all fell before the Texans' knives. An infantry colonel got together a following under cover of some trees; a Texas sharpshooter killed him, and the following scattered. Almonte, the Chief-of-Staff, rounded up four hundred men and succeeded in retreating out of the panic zone. Santa Anna rushed from his tent commanding every one to lie down. A moment later he vaulted on a black horse and disappeared.

General Houston rode among the wreckage of the Mexican camp. He- was on his third horse, and his right boot was full of blood. "A hundred steady men," he said, "could wipe us out." Except for a handful of Regulars, the army had escaped control of its officers, and was pursuing, clubbing, knifing, shooting Mexicans wherever they were found. Fugitives plunged into the swamp and scattered over the prairie. "Me no Alamo! Me no Alamo!" Some cavalry bolted for bridge-less Vince's Bayou. The Texans rushed them down a vertical bank. A hundred men and a hundred horses, inextricably tangled, perished in the water.

Houston glanced over the prairie. A gray-clad column, marching with the swing of veterans, bore toward the scene of battle. After a long look the General lowered his field-glass with a thankful sigh. Almonte and his four hundred were surrendering in a body.

As the sun of Austerlitz set General Houston fainted in Hockley's arms. His right leg was shattered above the ankle. The other Texan casualties were six killed and twenty-four wounded. According to Texan figures the Mexicans lost 630 killed, 208 wounded and 730 prisoners, making a total of 1568 accounted for. This seems to be about 200 more men than Santa Anna had with him.

The battle proper had lasted perhaps twenty minutes. The rest was in remembrance of the Alamo. This pursuit and

THE PLAIN OF ST. HYACINTH 253

slaughter continued into the night. The prisoners were herded in the center of a circle of bright fires. "Santa Anna? Santa Anna?" the Texans demanded until officers began to pull off their shoulder-straps. But no Santa Anna was found.

The Texans roystered all night, to the terror of the prisoners who designated their captors by the only English words their bewildered senses were competent to grasp. A woman camp-follower threw herself before a Texan soldier. "Sefior God Damn, do not kill me for the love of God and the life of your mother!" The soldier was of the small company of Mexicans that had fought under young Zavala. He told his countrywoman not to fear. "Sisters, see here," the woman cried. "This Sefior God Damn speaks the Christian language like the rest of us!"

6

After a night of pain General Houston propped himself against a tree, and Surgeon Ewing redressed his wound which was more serious than had been supposed. While the Surgeon probed fragments of bone from the mangled flesh, the patient fashioned a garland of leaves and tastefully inscribed a card "To Miss Anna Raguet, Nacogdoches, Texas: These are laurels I send you from the battle field of San Jacinto. Thine. Houston."

The Commander-in-Chief also penciled a note which was borne as fast as horseflesh could take it to the hands of one who deserved his own share of the laurels—Andrew Jackson.

All day bands of scared prisoners were brought in. But no Santa Anna, no Cos. This was more than vexing. The Texans wished simply to kill Cos for violation of parole, but Santa Anna might escape to Filisola and return with thrice the army Houston had just defeated. With the President of Mexico in his hands, however, Houston could rest assured that he had won the war, not merely a battle.

Toward evening a patrol of five men rode into camp. Mounted behind Joel Robison was a bedraggled little figure in

a blue cotton smock and red felt slippers. The patrol had found him near the ruined Vince's Bayou bridge seated on a stump, the living picture of dejection. He said he had found his ridiculous clothes in a deserted house. He looked hardly worth bothering to take five miles to camp and would have been dispatched on the spot but for Robison, who was a good-hearted boy, and spoke Spanish. Robison and his prisoner chatted on the ride. How many men did the Americans have? Robison said less than eight hundred, and the prisoner said that surely there were more than that. Robison asked the captive if he had left a family behind. "Si, senor." "Do you expect to see them again?" The little Mexican shrugged his shoulders. "Why did you come and fight us?" Robison wished to know. "A private soldier, senor, has little choice in such matters."

Robison had taken a liking to the polite little fellow and was about to turn him loose without ceremony among the herd of prisoners, when the captives began to raise their hats.

"El Presidente! El Presidente!"

An officer of the guard ran up and with an air that left the Texan flat, the prisoner asked to be conducted to General Houston.

Sam Houston was lying on a blanket under the oak tree, his eyes closed and his face drawn with pain. The little man was brought up by Hockley and Ben Fort Smith. He stepped forward and bowed gracefully.

"I am General Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna, President of Mexico, Commander-in-Chief of the Army of Operations. I place myself at the disposal of the brave General Houston."

This much unexpected Spanish was almost too great a strain upon the pupil of Miss Anna Raguet. Raising himself on one elbow, Houston replied as words came to him.

"General Santa Anna!—Ah, indeed!—Take a seat, General. I am glad to see you, take a seat!"

The host waved his arm toward a black box, and asked for an interpreter. Zavala came up. Santa Anna recognized him.

THE PLAIN OF ST. HYACINTH 255

"Oh! My friend, the son of my early friend!"

The young patrician bowed coldly. Santa Anna turned to General Houston.

"That man may consider himself born to no common destiny who has conquered the Napoleon of the West; and it now remains for him to be generous to the vanquished."

"You should have remembered that at the Alamo," Houston replied. 17

General Santa Anna made a bland Latin answer that loses much in translation. Houston pressed the point. What excuse for the massacre of Fannin's men? Another Latin answer. Another blunt interrogation, and for the first time in his amazing life Santa Anna's power of self-command deserted him. He raised a nervous hand to his pale face and glanced behind him. A ring of savage Texans had pressed around, with ominous looks on their faces and ominous stains on their knives. Santa Anna murmured something about a passing indisposition and requested a piece of opium.

The drug restored the prisoner's poise, and formal negotiations were begun. Santa Anna was deft and shrewd, but Houston declined to discuss terms of peace, saying that was a governmental matter not within the province of a military commander. Santa Anna proposed an armistice, which Houston accepted, dictating the terms which provided for the immediate evacuation of Texas by the Mexican Armies. Santa Anna wrote marching orders for Filisola and the other generals. Houston beckoned to Deaf Smith, and the orders were on their way.

Houston had Santa Anna's marquee erected within a few yards of the tree under which the Texas General lay, and restored the captive's personal baggage to him. Santa Anna retired to change his clothes, and General Houston produced an ear of corn from beneath his blanket and began to nibble it. A soldier picked up a kernel and said he was going to take it home and plant it, A genius had opened his lips!

Houston's great voice summoned the men from their cordial

discussion of the mode of General Santa Anna's execution. "My brave fellows," he said scattering corn by the handful, "take this along with you to your own fields, where I hope you may long cultivate the arts of peace as you have shown yourselves masters of the art of war."

Irresistible. "We'll call it Houston corn!" they shouted.

"Not Houston corn," their General said gravely, "but San Jacinto corn !" 18

And thousands of tasseled Texas acres to-day boast pedigrees that trace back to the San Jacinto ear. Three days after the corn incident, Houston had forgotten the name, however, and in his official report nearly wrote it the battle of Lynchburg.

7

When President Burnet arrived with as much of his travel-stained government as could be picked up on short notice, General Houston was receiving Mrs. McCormick who bore a verbal petition to remove "them stinking Mexicans" from her land.

"Why, lady," protested General Houston, "your land will be famed in history as the spot where the glorious battle was fought."

"To the devil with your glorious history," the lady replied. "Take off your stinking Mexicans." 19

Mr. Burnet also found much to deplore, including General Houston^ reported use of profanity. He and his satellites swarmed over the camp, collecting souvenirs and giving orders without notice of the Comi..ander-in-Chief. Sidney Sherman and the new Colonel Lamar were much in the company of these statesmen. Leaning on his crutches, Houston watched the government confiscate the fine stallion of Almonte, which, after the sale of some captured material at auction, had been presented to the General by his soldiers. Had Sam Houston raised his hand those soldiers would have pushed Mr. Burnet into the San Jacinto. Even greater tact was required to preserve the

THE PLAIN OF ST. HYACINTH 257

life of Santa Anna, whose guards would have slain him except for Houston.

The Commander's wound had become dangerous, and Doctor Ewing said he must go to New Orleans for an operation. When President Burnet and Cabinet boarded their vessel to return to Galveston Island, Houston was not asked to accompany them. When he applied for permission, it was refused. But the Captain of the boat declined to sail without the General, and Secretary of War Rusk and his brother carried him aboard. Mr. Rusk was still Houston's friend and had made the last part of the campaign with the Army.

Passage on a Texas naval vessel sailing for New Orleans was likewise refused, and Surgeon Ewing, who had accompanied his chief to Galveston Island against President Burnet's order, was dismissed from the service. Houston's condition was alarming. Doctor Ewing feared lockjaw would develop before he could reach New Orleans. While Houston was being lifted on board a dirty little trading schooner, Burnet regaled the vast refugee camp on the island with tales of the General's private life. When these reached the ears of a newly landed company of southern volunteers, a message written by a hand so stricken that it could hardly guide a pen was all that saved the official dignity of the Provisional President.

"On board Schooner Flora "Galveston Island, 11th May 1836 "The Commander-in-Chief . . . has heard with regret that some dissatisfaction existed in the army. If it is connected with him, or his circumstances, he asks as a special favor, that it may no longer exist. . . . Obedience to the constituted authorities ... is the first duty of a soldier. . . . The General in taking leave of his companions in arms, assures them of his affectionate gratitude.

CHAPTER XX

"The Ceisis Requires It"

Foe seven days the little Flora rolled in a storm before it beat into the churning Mississippi and at noon on Sunday, May 22, 1836, arrived at New Orleans. The levee was thronged with people.

Not since Jackson's victory at Chalmette had America been so stirred by a piece of military news. The story of San Jacinto was not believed at first. After the Alamo and Goliad, the extermination of the bands of Grant and Johnson, the flight of the government and of the people, and the dismal dispatches that Houston was falling back, still falling back, the overwhelming intelligence of the capture of the President of Mexico and the annihilation of his army was incredible. When the confirmation came cannon boomed, men paraded, and in the Senate Thomas Hart Benton called Sam Houston another Mark Antony.

General Houston lay in a stupor on the uncovered deck of the Flora. Captain Appleman believed his passenger to be a dying man. When the Flora touched the wharf a crowd surged on board, and the Captain thought that his boat would be swamped. They started to lift Houston from the deck. With a cry of pain and a convulsive movement of his powerful left arm he flung them off. A man bent over the sufferer. The years rolled back and Sam Houston recognized the voice of William Christy, with whom he had served in the United States Army. A band struck up a march; Houston told Christy to

hold off the crowd and he would get up by himself. Leaning on his crutches he lurched against the gunwale.

His wild appearance stunned the crowd. General Houston's coat was tatters. He had no hat. His stained and stinking shirt was wound about the shattered ankle. The music stopped, the cheering stopped and a schoolgirl with big violet eyes began to cry. Her name was Margaret Lea. As he was lifted to a litter, General Houston fainted.

At the Christy mansion in Girod Street, three surgeons removed twenty pieces of bone from the wound. Recovery seemed by no means certain, and crowds lingered in front of the house. On June second Houston received a few visitors, but fainted during their call. Ten days later bad news came from Texas. Sam Houston gave his host a saddle that had belonged to Santa Anna and, although his life was still in danger, set out by land for the Sabine.

His strength failing on the journey, Houston was obliged to lay over en route. On July fifth he reached San Augustine and found the town in a state that was a fair example of the confusion prevailing in the Republic. Burnet was impotent. Few could keep track of the Cabinet, it changed so fast. President Burnet had negotiated two treaties with Santa Anna—one public, the other secret. The former provided for the cessation of hostilities and the return of Santa Anna to Vera Cruz. In the secret treaty Santa Anna promised to prepare the way for Mexican recognition of the independence of Texas. Two Cabinet members refused to sign the treaties, holding that Santa Anna had forfeited his life. One of these was Secretary of War Mirabeau Buonaparte Lamar, the afflorescent stranger who had led the cavalry at San Jacinto.

Nevertheless, Burnet hustled the prisoner aboard the Texas man-of-war Invincible which was spreading canvas to depart when the steamer Ocean entered Velasco harbor with two hun-

dred and fifty adventurers under Thomas Jefferson Green, of North Carolina. Green boarded the Invincible and dragged Santa Anna ashore in manacles while a mob on the beach howled its approval. Burnet's humiliation was complete. The Army, growing in numbers and in turbulence, scorned his authority. The civil population, huddled in refugee camps or trekking back to burned towns and desolated ranches, was a law unto itself. The Executive blamed Houston for his troubles, and in an effort to undermine the disabled leader's influence, shifted Lamar from the Cabinet back to the Army which was commanded by Houston's friend Rusk.

The first letter Houston received in San Augustine was from Rusk begging the Commander-in-Chief to hasten to the army. "First they mounted you & tried to destroy you [but] finding their efforts unavailing the[y] . . . have been hammering at mee and really trying to break up the army. . . . A vast deal depends on you. You have the entire confidence of the army and the people." 1 Four days later he wrote again, communicating a rumor that was to sweep Texas. Mexico, he said, was contemplating a new invasion. Six thousand troops were at Vera Cruz, four thousand at Matamoras. The Texans were without supplies. "Confusion prevails in the Country. The Cabinette I fear as a former Government has done, have been engaged in trying to destroy the Army. . . . The Army and People are Exasperated." 2 When, repeated Rusk, could Houston place himself at the head of the troops? A sinister idea had begun to lay hold of the grumbling soldiery.

To Houston the gravest feature of the situation was the rumored invasion. Resting on his crutches, he appealed to a mass meeting in San Augustine to support the government, and one hundred and sixty men marched for the frontier. With East Texas denuded of troops, the Indians grew restive and once more terror took the hearts of the Administration.

General Gaines and his Regulars were on the American side of the Sabine. Stephen F. Austin scrawled a note to Houston. "It is verv desirable that Gen Gains should establish his head

quarters at Nacagdoches. . . . Use your influence to get him to do so, and if he could visit this place [Columbia, the seat of government] & give the people here assurances of the good faith of Gen. Santa Anna in the offers and treaties he has made you & with this Govt" that also would be helpful.

At Phil Sublett's house in San Augustine, Houston took Austin's note from the hand of the courier. He penciled an asterisk after the word "treaty" and wrote on the margin, "I made no treaty." So much for keeping the record straight. At the foot of the sheet Houston added these lines: "General I refer this letter to you and can only add that such a step will . . . save texas. Your Friend Sam Houston." 3

Gaines declined to concern himself with treaties, but he sent some dragoons to Nacogdoches, Jackson describing the intervention as a measure to safeguard our frontier against the Indians.

3

No person in America had shown greater interest in the progress of the war in Texas than Andrew Jackson. The note that Sam Houston wrote on the battle-field was thrust into the hands of General Gaines at the international boundary, and Lieutenant Hitchcock risked his life in a dash through hostile Indian territory to save a few hours on the way to Washington. Jackson was recovering from a severe illness. He saw Hitchcock at once.

"I never saw a man more delighted," the young officer wrote in his journal. "He read the dispatch . . . exclaiming over and over as though talking to himself, 'Yes, that is his writing. I know it well. That is Sam Houston's writing.' . . . The old man ordered a map . . . and tried to locate San Jacinto. He passed his fingers excitedly over the map. ... 'It must be here. . . . No, it is over there." 4

In the flush of his ardor Jackson dashed off a note of congratulation to his old subaltern. Houston had won a

victory greater than New Orleans. Houston had attacked; Jackson had stood on the defense. And after that, a second letter. Success to Texas! Money was being raised in the United States and Jackson's contribution, "was as much as I could spare." 5

The occupation of Nacogdoches by Gaines stimulated recruiting in the United States.

"My brother Tom was just out of college and I was a freshman. Tom at once organized a Company of Volunteers in Washington, Pennsylvania. . . . We marched to Wheeling and took a little stern wheel boat named the * Loyal Hannah* for Louisville. ... A boat arrived from below with word that . . • another steamer bearing President Jackson . . . would soon be along. I was color bearer . . . and had received the flag from the hands of my sister Catherine. . . . When we met his [Jackson's] boat the flag was lowered in salute and three cheers given. . . . Lemoyne, the great Abolitionist, was on that boat and demanded of the President why it was that armed bodies of men were allowed to recruit in the United States to make war on Mexico. To which General Jackson replied, 'That Americans had a lawful right to emigrate and to bear arms.' " 8

Jackson considered that his official acts had been studiously correct. In response to protests from Mexico and murmurings in the chancellories of Europe, he had issued a solemn proclamation of the official disinterestedness of the United States. He had rebuked Commissioner Austin who during his tour of the States, had made so bold as to presume otherwise. He had directed his United States district attorneys to prevent violations of our neutrality. Indeed, upon receipt of this instrument, District Attorney Grundy, of Nashville, Jackson's home, had paused in his occupation of recruiting a company for Sam Houston to publish a stem warning. "I will prosecute any man in my command who takes up arms in Tennessee against Mexico and I will lead you to the border to see that our neutrality is not violated . . . on our soil. 997

Jackson's confidant, Samuel Swartwout, wrote to Houston:

"THE CRISIS REQUIRES IT" 263

"The old chief, encourages us to believe that you are not abandoned. . . . Genl Stewart left here the day before yesterday for Pensacola. His real object we suppose to be the command of the West India fleet preparatory to the reception of the answer from Mexico, to some queries or questions that the old man has sent to her. . . . We think your Independence will soon be acknowledged. . . . We shall press hard for annexation. . . . My noble Gen. you have erected a monument, with your single hand & in a day that will outlive the proudest . . . monarchies of the old world. . • . We have entertained your name in a proper manner . . . over the bottles by coupling your name and achievements with Washington and Jackson. . . . P. S. Mrs. Swartwout, one of your greatest admirers, sends her kindest regards to you, and my Daughter, now quite grown, begs me to say the same." 8

From Congressman Ben Currey, of the intimate Jackson circle:

"You are by Genl Jackson Mr Van Buren Maj Lewis Colo Earle etc ranked among the great men of the earth. . . . I . . . raised a company of fifty men to join you. . . . Colo Earl has a splendid snuff box which he intends to send you by the first safe conveyance. I gave Mrs Addison formerly Miss Ellin Smallwood ... a splendid entertainment on account of expressions of friendship for you evidences of which she wears on her finger. ... I find in her album a poem in honor of you. . . . Hays is abusing you for not putting Santa Anna to death. . . . Genl Jackson says he is rejoiced at your prudence." 9

Discredited old Aaron Burr sighed ruefully. "I was thirty years too soon."

4

When Houston heard of the kidnaping of Santa Anna, he stormed at the weakness of Burnet who managed, however, to retrieve the captive from Thomas Jefferson Green. Green rejoined the Army, which liked his style, and two colonels marched to overthrow the government and seize the Mexican President. Sam Houston halted them with a letter. "Texas, to be re-

spected, must be considerate, politic . . . just. Santa Anna living . . . may be of incalculable advantage to Texas in her present crisis." Santa Anna dead would be just another dead Mexican. 10

Burnet saw that his course was run. He called a general election to choose a new president and to ratify the constitution, but there was some embarrassment because the files of the Republic contained no copy of that document. In the exodus from Washington on the Brazos the Secretary of the Convention, Mr. Kimble, had disappeared with the manuscript. He ended his retreat at Nashville, Tennessee, however, giving the constitution to an editor who published it, but lost the original. A Cincinnati paper copied it from the Nashville sheet, and ten days after the call for an election Gail Borden's serviceable Texas Telegraph made a reprint from its Ohio contemporary. Burnet put a copy of the Telegraph in his desk, and the archives were in order. 11

Austin and ex-Governor Henry Smith offered their candidacies for president and Texas began to stir—but not with enthusiasm for the election. The Mexican invasion scare had blown over, and the unoccupied army was out of hand again. General Thomas Jefferson Green was a big man now. He proposed an activity for the troops. "March immediately against the town of Matamoras . . . carry & burn the town destroy the main people if they resist & retreat . . . before they can have time to recover from their panic." 12 Rusk relayed word of the design to Houston but before anything happened useful George Hockley rode into camp with news that Sam Houston was on his way to the army!

The men were thrilled. The absent Commander-in-Chief had become a legend with the ranks. Rusk dashed off a long happy letter, Matamoras was eclipsed and the election came into its own as an object worthy of the Army's notice.

Sam Houston did not go to the army. He sat in tranquil San Augustine with his bandaged leg on a pillow, one of Phil Sublett's negroes in attendance and a Miss Barker reading

from a novel. Miss Barker had journeyed from Nacogdoches to cheer the wounded hero. He said (but not to Miss Barker) that her blue eyes reminded him of Anna Raguet, who stayed at home.

5

Houston could have obliterated President Burnet and taken charge of Texas under any title that would have suited his whim, but he passed the warm July days in seclusion, bestirring himself only to save the life of Santa Anna and to keep Burnet on his uncomfortable seat. The approaching election found General Houston still uninterested, except to remark that Rusk was a good man and might do for president.

Rusk was flattered. He was popular with the army, and something like a boom began to agitate the ranks. Thomas Jefferson Green pondered in his tent and informed Houston that Rusk would be "satisfactory." But the paramount issue with General Green, was the execution of "Santo Ana." "Great God when will this childish play cease." 13

General Santa Anna himself was not indifferent to the paramount issue. He smuggled a letter to the hermit of San Augustine, undertaking a delicate task of instruction. "Muy Esti-mado Senor. . . . Your return has appeared to be very apropos . . . because it seems to me that your voice will be heard and properly respected." The difficulties that confronted Texas "and . . . embarrass my departure for Mexico . . . you can easily remove with your influence in order that Texas may owe you its complete happiness." The cause of Texas had been harmed by Houston's "absence, which is to be deplored. Hurry yourself then to come among your friends. Take advantage of the favorable time that presents itself and believe me, in all circumstances your affectionate and very grateful servant, Ant.o Lopez de Santa Anna." 14

After a fortnight of meditation, the conscientious Rusk wrote Houston a fine letter of gratitude "that you should feel me worthy of the Presidential Chair but my age precludes me

from running." General Rusk was thirty years old and had much to learn about politics. He was perplexed. Houston was his idol, and like Santa Anna, Rusk failed to understand why he should remain aloof. "This is an important office. I would rather vote for you than any other man." 15

Rusk wrote on the ninth day of August. Texas would vote on September fifth. During the week ending August twentieth destiny showed its hand. Sam Houston's name was presented for the presidency by spontaneous meetings in various parts of the Republic. On August twenty-fifth, eleven days before the election, Houston consented to run. His announcement was the soul of brevity. "The crisis requires it." Houston received 5,119 votes to 743 for Smith and 587 for Austin. The constitution was adopted, and a proposal of annexation to the United States was carried almost unanimously. Mirabeau B. Lamar was elected vice-president.

Within certain limits Mr. Burnet could choose his own time for relinquishing office. He retired, however, with a degree of dispatch that moved his friend, General Lamar, to charge the President-Elect with unseemly precipitation in donning the toga. In any event on the morning of October 22, 1836, Burnet submitted his resignation and Congress ordained the inauguration to take place at four that afternoon. By chance or design Sam Houston was in Columbia, accessible to the committee of Congress which, in the execution of the time-saving program, conducted him to the big barn of a building that served as their meeting-place. Grumbling a little over the lack of preparation, General Houston advanced to a table covered with a blanket and took the oath.

The President made a speech, and in conclusion disengaged the sword of San Jacinto. The quotation that follows appears on page eighty-seven of the House Journal, First Session, First Congress of the Texas Republic, the words in brackets having been inserted by the official reporter.

"It now, sir, becomes my duty to make a presentation of

this sword—this emblem of my past office. [The President was unable to proceed further; but having firmly clenched it with both hands, as if with a farewell grasp, a tide of varied associations rushed upon him; . . . his countenance bespoke the . . . strongest emotions; his soul seemed to have swerved from the hypostatic union of the body. . . . After a pause . . . the president proceeded:] I have worn it with some humble pretensions in defense of my country; and, should . . . my country call ... I expect to resume it."

Not every orator is a hero to his stenographer.

CHAPTER XXI

A Toast at Midnight

Although "the want of a Suitable pen" delayed the preparations of some preliminary papers, President Houston took hold of his responsibilities with little loss of time or waste of motion. The old barn at Columbia vibrated with his energy. Appointments, commissions, instructions, approvals, rejections, streamed day and night from a gaunt room wherein the Executive's labors kept three secretaries busy, Congress in a trance and the Cabinet in a state of prostration.

Everything had to be done, everything provided—instantly, it seemed. What was this? "In the name of the Republic of Texas, Free, Sovereign and Independent. . . . To All whom these Presents Shall come or in any wise concern: I, Sam Houston, President thereof send Greetings." Sam signed his name. He enjoyed doing that, for his swelling autograph was a work of art. But the paper called also for the great seal of the Republic. The President altered the document to read, "signed and affixed my private Seal, there being no great Seal of office yet provided." From his shirt he stripped an engraved cuff link, the design of which he impressed in wax upon the official paper.

The home-made heraldry on Sam Houston's cuff button served as the seal of the Texas Republic until Anna Raguet consented to assist in designing a permanent one. The button exhibited a dog's head, collared, encircled by an olive wreath,

below which was a script capital H. Above the dog's head was a cock and above the cock the motto: try me. This picto-graph of the duel with White was a modification of the ancient coat of arms of the Scottish barons of Houston which represented an incident in the life of an early soldier of the clan.

Sam Houston believed in the influences of heredity. His imagination was impressed by symbols and signs. In his inaugural address he said that neither chance, design, nor desire, but "my destiny," had guided his steps to the chief magistracy of the new nation. The rooster and the pups that figured in the White duel bore sufficient kinship to the martlets and hounds whose images had safeguarded generations of Houstons to convince Sam that they might have something to do with his future.

Houston chose a notable Cabinet, inducing his rivals for the presidency to accept portfolios. Austin was made Secretary of State and Henry Smith Secretary of Treasury. Crushed by the staggering proportions of his defeat, Stephen F. Austin would have gone to his grave an embittered man but for the magnanimity of the victor. Austin was ill and had prepared to isolate himself in a woodland cabin, but the impulse to duty remained, and he accepted the most responsible and burdensome post in the government.

Rusk again became Secretary of War. Of the Army of San Jacinto few remained in service. Most of the early volunteers and professional adventurers having been killed off beforehand, independence was won mainly by the old settlers with family responsibilities. They were now at home gathering the first crop of San Jacinto corn. Nevertheless, Texas had the largest military force of its history, fed by daily arrivals from

the States. Their commander was Felix Huston, a forceful swashbuckler from Mississippi. The men wanted action, and on the lips of Felix was a dangerous word—Matamoras.

An obstreperous Army had upset one Texas Government and made another ridiculous. Secretary Rusk's attitude toward the Matamoras idea did not satisfy the President, and Mr. Rusk resigned after holding office a month. He was succeeded by William S. Fisher, a military adventurer but a staunch man who had proved his fealty at Brazos Bottoms.

The unrest of the Army increased. Felix Huston, wrote one of his men, "was as ambitious as Cortez. ... It was his thoughts by day and his dream at night to march a conquering army into the 'Hall of the Montezumas.' During intervals at drill ... he would pour floods of burning eloquence and arouse . . . passions by illusions to . . . the tropical beauties of the land far beyond the Rio Grande. . . . Had he chosen to do so he could have marched that army to Columbia with the avowed purpose of driving Sam Houston and the Congress into the Brazos River. . . . Felix Huston was a man of might but there was a mightier and far greater man in the executive cottage at Columbia. That man was Sam Houston. . . . Without a Herald and without parade he suddenly appeared [in camp]. His manner was calm and solemn. . . . The few men who had fought by his side at San Jacinto gathered around him as soldiers always cluster about a loved chief. . . . Houston's first act was to visit the hospital and inquire into the condition of the sick. . . . He reviewed the little army and addressed the men as a kind father would his wayward children. He told them the eyes of the civilized world were on them and appealed to them to disprove the calumnies sown broadcast against Texas. . . . His sonorous voice like the tones of a mighty organ rolled over the column. For a time at least the army felt his influence and it seemed as though all danger had passed." 1

The duties of the Secretary of Navy were nominal since the Navy was detained in Baltimore for non-payment of a

repair bill. James Pinckney Henderson, the good-looking and gay young Attorney-General, and Robert Barr, the Postmaster General, organized their departments on credit. Although the Republic was unable to pay cash for feed for the post-riders' horses, mail service was established and within four months a supreme court, district courts and tribunals in each of the twenty-three counties were in operation.

The administration of justice presented especial complications. The white population, distributed over an area the size of France, numbered thirty thousand. Hitherto, the process of atonement for crime in Texas had used up a good deal of rope, but with few objections on the whole.

The district judge selected for the upper Brazos was Robert M. Williamson, who had killed his opponent in duel in Georgia. When the lady in the case married a disinterested third party, the disappointed marksman came to Texas to devote himself to ranching and the elixirs of forgetfulness. One of Judge Williamson's legs being useless below the knee, he strapped it up behind him and substituted a wooden leg to walk on. This gave him the nickname of Three-Legged Willie.

On the first tour of his jurisdiction Three-Legged Willie was welcomed with the information that the inhabitants desired none of Sam Houston's courts there. Judge Williamson unpacked his saddle-bags, and establishing himself behind a table, placed a rifle at one elbow and a pistol at the other. His Honor had a way of snorting when he spoke. "Hear ye, hear ye, court for the Third District is either now in session or by God somebody's going to get killed." 2

Shortly before his inauguration Sam Houston complied with a request of General Santa Anna to visit him at his place of confinement on a plantation near Columbia. The Napoleon of the West embraced his Wellington. His head did not reach the Texan's shoulders. He wept and called Houston a mag-

nanimous conqueror. He asked General Houston's influence to obtain his release in return for which Santa Anna guaranteed the acquiescence of Mexico to the annexation of Texas by the United States.

The idea of using Santa Anna to assist in a solution of the entangling diplomatic problems of the young Republic had previously occurred to Houston. He had written Jackson about it, but Jackson did not see how Santa Anna could help. The Mexican Minister at Washington had warned that no agreement made by Santa Anna while a prisoner would be considered binding.

What to do with the distinguished captive was a puzzle. There was still a healthy sentiment for his execution, and General Santa Anna was eager to cooperate in relieving Texas of the embarrassment of his presence. After the inauguration he addressed another letter to "Don Sam Houston: Muy Sefior mio y de mi aprecio" setting forth the pleasing intelligence that the diplomatic issues confronting Texas were "very simple" of solution. Texas desired to be admitted to the American union. The American union desired it. Only Mexico remained to be consulted and Santa Anna would be pleased to go to Washington and "adjust that negotiation." 3

Houston was skeptical of any pourparlers that Santa Anna might undertake, but he did wish to get him out of Texas. "Restored to his own country," Houston said, Santa Anna "would keep Mexico in commotion for years, and Texas will be safe." Houston asked Congress for authority to release the prisoner. Congress declined, and passed an inflammatory resolution. Houston vetoed the resolution, gave Santa Anna a fine horse and sent him on his way under escort of Colonel Barnard E. Bee. Santa Anna borrowed two thousand dollars of Bee and improved his wardrobe.

William H. Wharton had already started to Washington as minister plenipotentiary with instructions to obtain the recognition of Texan independence and annexation. But these were not, the only strings to the bow of Houston's foreign

policy. Should the attitude "of the United States toward Texas be indifferent or adverse," Mr. Wharton was to cultivate "a close and intimate intercourse with the foreign ministers in Washington," particularly the British and French. 4

When Wharton had journeyed as far as Kentucky, he reported opposition to annexation by "both friends and foes" of Texas. "The leading prints of the North and East and the abolitionists . . . oppose it on the old grounds of . . . extension of slavery and of fear of southern preponderance in the councils of the Nation," while "our friends" proclaimed that "a brighter destiny awaits Texas." This bright destiny did not contemplate an independent Texas with strong friends in Europe, which was Sam Houston's alternative to annexation. It contemplated dismemberment of the Federal Union by the establishment of a slaveholding confederacy of which Texas should be a part. "Already has the war commenced. . . . The Southern papers . . . are acting most imprudently. . . . Language such as the following is uttered by the most respectable journals. . . . [*]The North must choose between the Union with Texas added—or no Union. Texas will be added and then forever farewell to northern influence. ['] Threats and denunciations like these will goad the North into a determined opposition and if Texas is annexed at all it will not be until it has convulsed this nation for several sessions of Congress." 5

Wharton anticipated no difficulty in obtaining the recognition of Texan independence, however, which was necessary to repair the desperate condition of the Republic's finances. Wharton reached Washington in December of 1836, but was unable to see the President who was ill and working on his message to Congress. The message was expected to recommend recognition, and Congress was expected to grant it.

Every straw bearing on the course of events at Washington was watched with feverish interest in the barn by the Brazos. The enormous detail work of the Texan foreign policy was handled by Austin who proved Houston's ablest lieutenant.

Thus two of the greatest figures an American frontier has produced forgot their mutual distrust in the close association of unremitting labor. Despite frail health no task was too obscure for the conscientious Austin. "The prosperity of Texas," he wrote to a friend, "has assumed the character of a religion for the guidance of my thoughts."

On the night before Christmas Austin left his fireless room in the Capitol and retired with a chill. On the twenty-seventh he was delirious. "Texas is recognized. Did you see it in the papers?" With these words he ceased to speak, and Houston dictated this announcement: "The father of Texas is no more. The first pioneer of the wilderness has departed. General Stephen F. Austin, Secretary of State, expired this day."

3

The dying words of the first pioneer were not prophetic. The minute guns announcing his passing had not ceased to boom when newspapers from the United States arrived with Jackson's message to Congress, which contained these bewildering lines:

"Recognition at this time . . . would scarcely be regarded as consistent with that prudent reserve with which we have heretofore held ourselves bound to treat all similar questions."

Wharton was dumfounded. Could the man who spoke of "prudent reserve" be the same Jackson who had striven for fifteen years to annex Texas—countenancing the seamy diplomacy of Anthony Butler to that end, speeding Americans with his blessing to Sam Houston's Army, contributing to Houston's war chest, and advising the victor of San Jacinto on the conduct of Texan affairs?