7

The Illusion of Consciousness

What is it like to be you? To wake up every morning, look at yourself in the mirror, and go about your daily life? What is it like to think all the things you think, to feel all the things you feel? It must be at least somewhat different from being me: whoever you are, you have your own history, your own experiences, your own memories, thoughts and desires. Your own life. Your own sense of being you.

And so we come to arguably the biggest mystery of the human brain: consciousness – our subjective experience of the world and all its perceptual contents, including sights, sounds, thoughts and sensations. A private inner universe that utterly disappears in states such as general anaesthesia or dreamless sleep. And something so mysterious that we still find it notoriously difficult to understand or even define.

Many have tried. In his famous 1974 essay, ‘What is it Like To Be a Bat?’, the American philosopher Thomas Nagel asks us to imagine changing places with a bat. His interest wasn’t in bats but in making the point that an organism can only be considered conscious ‘if and only if there is something that it is like to be that organism – something that it is like for the organism.’1 We could call this the subjective experience of being a bat; a state of being that is comparable to the bat’s.

Let’s take Nagel up on his challenge and imagine being a bat. A bat’s experience must be starkly different from our own. Most use echolocation to navigate and find food, releasing sound waves from their mouths or noses that bounce off objects and return to their ears, informing them of the object’s shape, size and location. Some bats glide through the air releasing slow and steady pulses of sound, which then rapidly speed up when they swoop down on their prey. Others calculate their speed relative to their prey using the Doppler effect (the change in sound frequency that happens when the source and/or the receiver are moving; the same reason an ambulance siren sounds differently as it passes). Being a bat, I imagine, would be to live in a shadowy, kaleidoscopic world of sound, instinct and twilight flight.

But is this really what it would be like, or have I simply tried to imagine that I am a bat? If there is in fact something that it is like to be a bat, is it merely a sense of bat subjectivity, or something more? It’s hard to say.

In the 1990s, the Australian philosopher David Chalmers took things further, proposing a hypothetical entity called the ‘philosophical zombie’: an exact, atom-for-atom duplicate of a human, indistinguishable from a real person in all its behaviour, only with no conscious experience whatsoever. Spooky, right? I envisage such a being to be a bit like Patrick Bateman, the protagonist villain of Bret Easton Ellis’s novel American Psycho, who at one point in the story reveals,

There is an idea of a Patrick Bateman, some kind of abstraction, but there is no real me, only an entity, something illusory, and though I can hide my cold gaze and you can shake my hand and feel flesh gripping yours and maybe you can even sense our lifestyles are probably comparable: I simply am not there.

Bateman is terrifying not for what his mind contains but for what it lacks. And here’s the point: if philosophical zombies are possible, Chalmers argued, it follows that conscious states might not be entirely connected to brain states – that there is something more to conscious life than neurons firing inside the brain.

If bats and zombies aren’t your thing, consider Mary the colour scientist. Mary specialises in the neurophysiology of colour vision, and thus knows everything there is to know about colour perception. She knows precisely how different wavelengths of light impinge on the retina and stimulate photoreceptors. She knows how they convert light into signals that are sent up the optic nerve to the primary visual cortex in the brain. And she knows all the cellular and molecular details of how the visual system eventually produces the experience of blue, green, red and so on.

But Mary has spent her entire life in a black and white room. She has never actually seen any colours; she has learnt about them and the world through black and white books and television programmes. One day, Mary escapes her monochrome prison and sees a brilliant blue sky for the first time. What changes? Does Mary learn something new upon seeing blue for the first time? Or is she unsurprised, since she already knows everything there is to know about how the brain processes blue in advance? If you think Mary learns something fundamentally new about the colour blue, you may consequently believe that physical facts about the world are not all there is to know.

Science still has no answer to these mind-bending thought experiments, but they are valuable because they encourage philosophers and neuroscientists to work together, to reconsider previous models and build a scientific framework for new accounts of how the brain gives rise to conscious thought. Most are essentially updated versions of the great philosopher René Descartes’ mind–body dualism. In Meditations on First Philosophy (1637), Descartes concluded that the mind was immaterial, something totally distinct from the physical properties of the brain. Consciousness, from this view, wasn’t so far removed from the Judeo-Christian notion of a soul, and indeed Descartes was strongly influenced by the Augustinian tradition of dividing soul and body. The resulting ‘Cartesian’ biology came to dominate thinking until 1949, when the British philosopher Gilbert Ryle ridiculed dualism as ‘the dogma of the ghost in the machine’.

Such thought experiments, however, can be misleading. Some scholars have pointed out that it is in fact tremendously difficult to imagine knowing everything there is to know – about colour, for instance. In consequence, we may be tying ourselves up in philosophical knots, mistaking what is merely a failure of imagination for genuine insight.

If this all sounds terribly confusing, that’s because it is. And it will remain so until we solve what’s called the ‘hard problem’ of consciousness: namely, why are any physical processes in the brain accompanied by conscious experience? If the brain is ultimately just a collection of molecules shuttling around inside the skull – the same molecules that comprise earth, rock and stars – why do we think and feel anything at all? Why does our extraordinary mind spring from soggy grey matter to begin with? It’s a problem that’s been with us for centuries, as opposed to the ‘easy problem’ of consciousness, i.e. explaining how the brain works. Examples of easy problems include the biology of neurons, the mechanisms of attention and the control of behaviour – practical problems that relate to our experience of the world and that are not as deeply mysterious as the hard problem. Problems we know we can solve, in other words.

Some neuroscientists believe we will never solve the hard problem. Just as a goldfish will never be able to read a newspaper or write a sonnet, Homo sapiens, these scholars argue, are cognitively closed to such knowledge. It is a great but impenetrable mystery. The psychologist Steven Pinker calls the hard problem ‘the ultimate tease… forever beyond our conceptual grasp.’ Echoing the view that consciousness remains outside the limits of human comprehension, one of the best entries in Ambrose Bierce’s The Devil’s Dictionary is the following:

Mind, n. A mysterious form of matter secreted by the brain. Its chief activity consists in the endeavor to ascertain its own nature, the futility of the attempt being due to the fact that it has nothing but itself to know itself with.

Others believe that if we just keep solving the easy problems, the hard problem will disappear. By locating and understanding what we call the neural correlates of consciousness (NCC) – neural mechanisms that researchers say are responsible for consciousness, typically gleaned using brain scans or neurosurgery to compare conscious and unconscious states – we will march ever closer to solving the mystery, until one day there is nothing left to solve. Defining an NCC starts as a process of elimination: the spinal cord and cerebellum can be ruled out, for instance, because if both are lost to stroke or trauma, nothing happens to the victim’s consciousness. They still perceive and experience their surroundings as they did before. The best candidates for NCC (so far) are a subset of neurons in a posterior hot zone of the brain that comprises the parietal, occipital and temporal lobes of the cerebral cortex. When the posterior hot zone is electrically stimulated, as it sometimes is during surgery for brain tumours, a person will report experiencing a menagerie of thoughts, memories, sensations, visual and auditory hallucinations, and an eerie feeling of surrealism or familiarity. So if the consciousness illusion is located anywhere, it might be in this mysterious region of the posterior cortex.

Still others believe that finding the neural correlates of consciousness will help us reveal the anatomy of consciousness, that is, its biological constituents in the brain, but that this will still not solve the hard problem because not all NCC will necessarily be a part of consciousness in the first place.2 It would be like scrutinising the inside of a computer and declaring, ‘Aha! This is where the Internet lives.’

There is another possibility, one I find the most compelling. There is no hard problem – because there is no such thing as consciousness in the first place. We have been misled, partly by the intriguing but ultimately false philosophical traditions of our forebears – most of whom were theologians first and scientists second – but mainly by the language we use to talk about consciousness. Whenever we say something ‘enters consciousness’, or ‘shifts conscious experience’, we are resurrecting Descartes’ mind–body dualism, creating a new kind of Ryle’s ‘ghost in the machine’. We fail to realise that the physical activity of our brain equals our conscious experience of the world. Any separation is to commit a category error: a fallacy that arises when we assign something with a quality that belongs to a different category. It would be a category error, for example, to ask about the lyrics of flowers, even though it might sound deep and mysterious, because flowers are categorised by genus, species, and often variety, but never by lyrics. Similarly, it would be a category error to visit the churches and galleries of Florence only to ask, ‘Where is the city?’.

The mistake we make when pondering consciousness is to place feelings and experiences into some mystical, nebulous category that is separate from the brain itself. But if I put my brain in a blender and ground it into a pulpy mush, all my conscious thoughts and feelings, all my memories and perceptions, would instantly vanish. To claim consciousness is ‘one’s experience’ is a tautology: you are your experiences, and your experiences are you.

The truth is that we still, despite all our enlightened science and empirical reasoning, struggle to simply accept the reality of materialism – the reality that there is only matter and energy in the universe, bound together by the scientific laws of nature. There are no non-physical minds or immaterial thoughts. Conscious states are brain states. As Nick Chater declares in his wonderful book The Mind is Flat,

There are no conscious thoughts and unconscious thoughts, and there are certainly no thoughts slipping in and out of consciousness. There is just one type of thought, and each such thought has two aspects: a conscious read-out, and unconscious processing generating the read-out. And we can have no more conscious access to these brain processes than we can have conscious awareness of the chemistry of digestion or the biophysics of our muscles.3

No doubt, this view gives short shrift to hypothetical bats and colour scientists. But good riddance, I say. Dualism is a philosophy that has plagued neuroscience for too long. Supporters of Nagel et al. might argue that even when we fully understand the neurobiology of consciousness, we will still be missing something essential. But what, exactly? No matter how you slice it, every conceivable answer relies upon mysticism and the denial of modern neuroscience.

We’ve been here before. For centuries, the theory of a ‘vital force’ (or élan vital) was proffered to explain how living things could arise out of non-living matter. The fire-like element phlogiston was once needed to explain oxygen; caloric fluid was advanced to explain heat. The illusion of consciousness is almost as absurd as the creationist notion of ‘irreducible complexity’: the belief that the molecular complexity of things like the bacterial flagellum is unassailable proof that it could not have arisen by a gradual step-by-step evolutionary process; God must be responsible.

Some people baulk at materialism because they fear it will denude life of its meaning. If human minds are just bags of chemicals with no mental depths to plumb, if all our actions are just the result of the electrochemical activity of neurons performing intelligent computations, what is the point of life? Here again the crisis stems from a misuse of language. ‘Just’ is not appropriate because these processes are extraordinary and many of them are beyond our current conception.

The reason we find materialism hard to swallow is because the words we use to describe brain activity are different to those we use to describe feelings. No one has trouble accepting that rain or snow are just other ways of discussing annual precipitation, but try telling someone that anxiety and happiness are just other ways of discussing serotonergic neuronal activity. Both types of language are part of the same equation, yet we focus on only one side.4

None of this is meant to remove consciousness from our evolutionary journey, any more than my emphasis on nurture removes the salience of nature. It is meant to topple our preconceived notions of consciousness in order to focus on what really matters: why consciousness seems the way that it does. To answer this question, we must explore how – and why – the illusion of consciousness evolved in the first place.

How Illusions Evolve

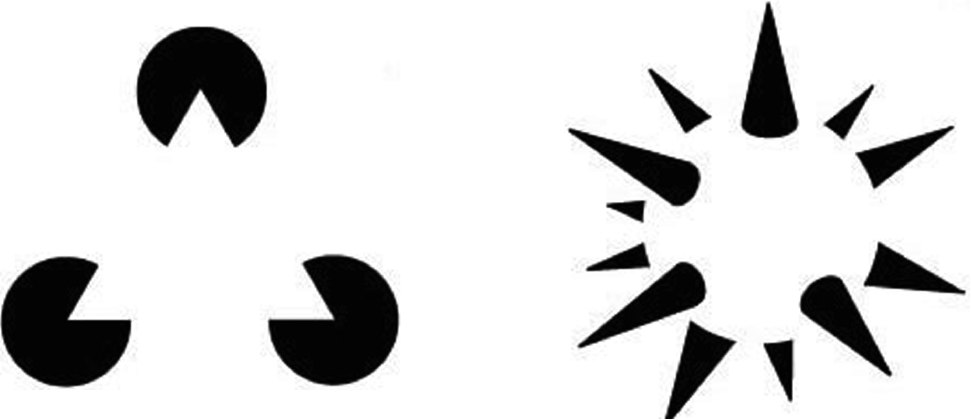

An illusion is not something that doesn’t exist; it is something that is not what it seems to be. When I wake in the middle of the night and perceive the washing on my clotheshorse as if it were a small child, I am – thankfully – having an illusion. The socks and T-shirts really do exist, and could (with a little artistic license) be taken to resemble a child. But it’s not a child. Just as the sun isn’t orbiting a flat earth, my mind has misinterpreted the facts. The same thing happens when we look at a missing-shapes illusion. The black shapes really do exist, but there is no white triangle or white sphere. Your brain has invented them.

With respect to consciousness, our experience exists but the notion of consciousness does not. It may seem as though our experiences are part of something larger – some grand cohesive narrative, a stream of consciousness, a movie-in-the-brain – yet this is no more real than the child I sometimes see in my clotheshorse. It is ‘a magic show that you stage for yourself inside your own head,’ says the psychologist Nicholas Humphrey.

Still, even magic shows need explaining. Did the illusion evolve for a particular purpose or is it a useless by-product: an evolutionary vestige like the human tailbone and goose bumps? In my view, whatever purpose the consciousness illusion might serve, it is principally no more than the emergent phenomena of brain activity – no more mysterious than the fact that sand forms dunes and birds fly in flocks.

Consider frogs. Their eyes do not tell their brains all the things that human eyes tell the human brain. Unlike humans, frogs do not construct a picture of the world in their heads; they see only what they need to see, namely moving edges, a little light, and insects. Inside a frog’s eye, in fact, is a network of nerves that act as an insect detector, which activates only when small moving objects enter the frog’s visual field, telling it to release its tongue to catch its prey. Remarkably, a frog can starve to death surrounded by dead flies – because if the flies don’t move, the frog doesn’t see them. Poor frogs, you might think. Yet we may be more like them than we realise, for we too have only a partial perception of reality.

In the 1950s, in an effort to treat people with severe epilepsy, some patients received a callosotomy, a surgical procedure that severs the corpus callosum: the nerves dividing the brain into left and right hemispheres. The surgery appeared to work, alleviating the patients’ seizures without producing any discernible side effects. These so-called split-brain patients allowed scientists to investigate the relative contributions of the ‘left-brain’ versus the ‘right-brain’.5 While it is a myth that some people use one side of their brain more than the other – that left-brained people are more analytical whereas right-brained people are more creative – the hemispheres do possess a high degree of functional independence. The left side of the brain controls the right side of the body, for instance, and vice versa. Anything that falls in the left visual field of each eye is projected to the right hemisphere, and vice versa. And the left hemisphere is mainly, though not exclusively, in charge of language. But the hemispheric independence of a split-brain patient also revealed something eerily puzzling about conscious experience.

In the experiment, a split-brain patient is asked to focus on a dot in the middle of a screen. Then a word – say, ‘spoon’ – is briefly flashed to the left of the dot, which only the patient’s right hemisphere sees. When asked what was seen, the patient (using her language-centred left hemisphere) will say ‘nothing’. Yet when the same patient is asked to pick up the ‘unseen’ object from a variety of objects using only her left hand (which is controlled by the right hemisphere), she will correctly select a spoon every time. If the patient is then asked what she now holds in her left hand, she will not be able to say what the object is until her left hemisphere is also allowed to see it. When everything is revealed, and the person doing the experiment asks her why she picked the spoon, she will either claim not to know or invent a story to fill in the gaps. This is very weird. It suggests that parts of the brain operate independently of each other, creating the impression of something being unconscious. It suggests that evolution has also hidden things from us.

Consider too the phenomenon of binocular rivalry. When one eye is presented with one image – a bus, say – and the other eye is presented with a different image – a tree, say – we do not experience a blending of the two images. Instead, the bus will be seen for a few seconds, and then the tree, and then the bus again, and so on, constantly flipping back and forth until we decide to look away. This is also pretty weird. Despite being completely awake and responsive to our surroundings, a complete overhaul of the contents of our conscious experience is occurring all the time.

We’re not really sure why the mind evolved this way, but just as wavelengths of light that our eyes cannot see and frequencies of sound that our ears cannot hear exist, evolution has clearly designed the brain to detect only particular features of the world around us. Like a glorified insect detector, the brain excludes unimportant details and zooms in on what really matters.

So where did the consciousness illusion come from? When and how did it evolve? For centuries these questions remained within the purview of theology and philosophy. Today there is a menagerie of evolutionary theories dedicated to this question. Some argue that consciousness arose as soon as single-celled life emerged, some 4 billion years ago. Others think that consciousness requires a nervous system, the first of which dates back to a wormlike organism about 550 to 600 million years ago, during the so-called Cambrian explosion. Still others, including the neurobiologist Bernard Baars, link consciousness to the arrival of the mammalian brain around 200 million years ago. The Oxford University neuroscientist Susan Greenfield thinks that consciousness evolved gradually as the brain size of hominids increased.6 The Cambridge University neuroscientist Nicholas Humphrey thinks that the consciousness of Homo sapiens may have been the first kind of consciousness to evolve.7

To reach the truth, we need to consider three viewpoints. The first is that only humans experience the illusion of consciousness. If you think that language and other uniquely human capacities are necessary for the illusion, you may agree with this viewpoint. I will add, though, that the brains of our ape cousins are organised in a remarkably similar way to our own, and research shows that chimpanzees are self-aware and may even be able to comprehend the minds of others. So it does look as though they almost certainly experience some form of the consciousness illusion. The second is that all species experience the illusion. An extreme version of this view is sometimes called panpsychism – the idea that everything from cosmic dust to a blade of grass has some form of consciousness. However, even if such consciousness does emerge from the interaction of subatomic particles, that still leaves us with the riddle of how these ‘micro-consciousnesses’ combine to create human experience. The third is that consciousness can be split into sensory consciousness – defined as our awareness of sensations in the present moment (the smell of fresh coffee, the blueness of the sky) – and higher-order consciousness – defined as our self-awareness, our thoughts about our thoughts and our ability to contemplate our fundamental nature and purpose. If true, this might mean that we have an on/off switch for consciousness, which some scientists believe exists deep in the brain. Nevertheless, by breaking up consciousness into parts including attention, sensation, introspection and so on, one could argue that we are no more explaining the illusion than explaining the purpose of a birthday cake by discussing flour types, flavour combinations and baking time.

Consciousness is likely to be a relatively modern invention. The brain continually changes and develops in response to input, with culture perhaps exerting the greatest influence of all. Given our capacity for symbolic thought, the illusion probably co-evolved with the appearance of specialised social skills, language and creative thinking. Today, a new theory called the Attention Schema Theory (AST) suggests that consciousness arose at some unknown point between 200,000 and 2 million years ago to deal with the continuous excess of information flowing into our minds.8 Human species during this time period ranged from Homo habilis to Homo erectus to Homo heidelbergenis to Homo neanderthalensis to Homo floresiensis to Homo sapiens (to name but a few). And each possessed a different brain size which, as we have seen, gave rise to different cognition and behaviour. But there’s a unifying factor about these early humans that helps explain where and how consciousness arose: their lives were a relentless test of where to focus their attention. In their struggle for survival, they needed to process a continuous excess of information. And so, by a strange form of neuronal competition, the theory goes, early human neurons had to select, moment-to-moment, which signals they were willing to convert into conscious awareness and which they were not. In essence the brain chose what it needed to know.

In the AST’s evolutionary story, attention is the essential pre-requisite for consciousness. For example, when a member of the Homo erectus species crept along the lake shore to hunt an antelope, her brain would first have had to suppress any competing signals for her attention, such as a bird or the wind rustling the grass. Then, as she got closer to the antelope, her attention became more focused; as far as her brain was concerned, it was now just her, the antelope, and her attention to the antelope. By constructing this level of attention, the brain concluded that such attention must belong to a separate, non-physical type of awareness. And with that, the illusion of consciousness was born. This theory fits nicely with our observations regarding optical illusions and split-brain patients, and also explains how the hardware for conscious thought could have emerged gradually over millions of years.

Then, enter Homo sapiens, fitted with a brain capable of igniting a social, linguistic and cultural explosion, roughly 60,000 to 40,000 years ago. As the brain expanded, the amount of information it could store and manage increased, leading to the phenomenon of cultural evolution. An important consequence of cultural evolution is a set of shared attitudes, values, beliefs and behaviours. Our brains have chosen what they need to know based on our social milieu. The consciousness illusion is not fixed. It evolved in tandem with the society that we created. It is our social and cultural experience of the world. The consciousness illusion is whatever we want it to be.

The Self Illusion

I opened this chapter with a question. Did you answer it? Could you answer it? Whatever you thought, I suspect a part of you considered it a reasonable question. Our everyday language is saturated, indeed obsessed, with our sense of self. Though our opinions, desires, hopes and fantasies may change over time, we return always to ourselves. As James Joyce wrote in Ulysses, ‘Every life is in many days, day after day. We walk through ourselves, meeting robbers, ghosts, giants, old men, young men, wives, widows, brothers-in-love, but always meeting ourselves.’9

But this way of thinking about ourselves is problematic. By talking about the brain as something that ‘I’ possess, I separate myself from it, thereby creating an illusory being, an everlasting author, who does not in fact exist. The Buddha understood this. In his sixth-century-BC doctrine of anatta he taught that the self is a changing, impermanent multitude of discrete parts: an individual’s identity, he said, is selfless. Building on this idea, the Oxford philosopher Derek Parfit (1942–2017) advanced two theories of personal identity: the ego theory and the bundle theory. Ego theorists believe there is a single, continuous self controlling our identity. Bundle theorists, on the other hand, believe there is no one self but a bundle, or collection of selves that ultimately defines us. Buddha was perhaps the first bundle theorist.

And certainly not the last. In A Treatise of Human Nature (1739), David Hume argued that the self is merely a bundle of different perceptions. It only feels like a continuous entity because memory seems to tie all our experiences together. But this is just another illusion. There is nothing supplementary to the feeling of continuity, no divine witness of the world and your earthly experiences. Hume writes:

For my part, when I enter most intimately into what I call myself, I always stumble on some particular perception or other, of heat or cold, light or shade, love or hatred, pain or pleasure. I never can catch myself at any time without a perception, and never can observe any thing but the perception.10

Like the Buddha, Hume discovered a fundamental truth about human experience: there is no experiencer. This was seen as heresy to ego theorists of the time. As Hume’s contemporary, the Scottish philosopher Thomas Reid, retorted: ‘I am not thought, I am not action, I am not feeling: I am something that thinks, and acts, and suffers.’11 But ponder what Reid is saying here. He is ‘not thought’, but ‘something that thinks’. What is that something, exactly? It is millions of interconnected neurons firing in the brain. It is a physical substance giving rise to behaviours, memories, and perceptions. It is thought. He then says he is ‘not action’, but something that ‘acts’. Well, okay, but actions and decisions occur due to the biological laws of living systems. The fact that we don’t yet fully understand those laws does not legitimise an illusion

More importantly, the concept of a unified self is bad science because it is unfalsifiable, that is, there is no experimental test to disprove it. A theory is only considered good science when it is falsifiable, meaning it is possible to devise an experiment that disproves the idea in question. If I hypothesise that all apples are sour, for instance, a quick test in the form of me eating a sweet apple will falsify my hypothesis. It might sound like a silly hypothesis, but the key point is that it is testable, because it is based in reality. Horoscopes are good examples of something that isn’t falsifiable. No one can disprove that a Gemini will have a dispute with a close relative, or whether a Capricorn wearing something light blue will be lucky between 11.00 a.m. and 1.15 p.m. The statements are too vague. Even if those predictions didn’t come true, that wouldn’t make them false because they still could have happened. The same is true with the self. It is too vague to be falsifiable.

Ask any neuroscientist today and she will probably agree that the illusion of self, while certainly being a subjective experience, is one that simply does not exist in nature. Just as cosmology no longer needs a God to explain the universe, neuroscience no longer needs a unified self to explain the mind. Like it or not, when you contemplate the existence of a self you discover that it is a mirage – just another form of mind–body dualism.

Ask yourself, am I the same ‘me’ as I was a moment ago? When you really think about it, the answer has to be no. After all, are you the same ‘you’ you were ten years ago? It’s doubtful. I for one am almost nothing like the person I was ten years ago; I’ve grown up, I’ve changed. Something we all do in one form or another. As the British philosopher Galen Strawson observed, ‘Many mental selves exist, one at a time and one after another, like pearls on a string.’12

The reason it feels like we have a continuing inner self is because we each possess what neuroscientists call the phenomenal self-model (PSM). This, according to its German pioneer Thomas Metzinger, is ‘a distinct and coherent pattern of neural activity that allows you to integrate parts of the world into an inner image of yourself as a whole.’13 In the brain, the PSM is thought to be located mainly in the prefrontal cortex, and some believe it is impaired in schizophrenia and extreme narcissism. To be clear: the PSM is not the self. As Metzinger notes, ‘no such things as selves exist in the world: nobody ever was or had a self.’ The PSM is merely the neural circuitry required for our feeling of ownership and agency – the ability to perceive your limbs as your limbs, for instance.

Today, we ceaselessly create new selves via social media platforms such as Facebook, Twitter and Instagram. These selves are often very different from the selves we manifest in face-to-face encounters: they each possess a distinct narrative, a unique voice and, usually, an idealised self-image. Moreover, each self can affect the other, producing a kaleidoscope of psychological complexity.

A startling consequence of multiple selves is that each can be a product of the social setting it finds itself in. Scholars in the new field of discursive psychology, a branch of science that investigates how the self is socially constructed, are particularly interested in how people’s pronouns affect their sense of self. According to these scholars, the self is a ‘continuous production’ built from words and culture. Until recently, the first-person pronouns ‘I’, ‘me’ and ‘mine’ predominated in Western society. Now, however, dozens of pronouns are used to express various identities: ‘ze’, ‘ey’, ‘hir’, ‘xe’, ‘hen’, ‘ve’, ‘ne’, ‘per’, ‘thon’ and more. Sticklers for grammar view this as an assault on the English language. Sticklers for tradition view it as a slippery slope to government-mandated speech codes. Yet far from being new-age gobbledygook or an omen of tyranny, novel pronouns in fact have a crucial social function. They reveal your personality, reflect important differences among groups and help knit communities together.

The construction of the self also appears to be a phenomenon in the wider animal kingdom. For decades, scientists have been searching for signs of self-awareness in animals. The most widely used test, called the mirror test, works by applying a spot of odourless dye to an animal’s forehead and then seeing if it tries to scrub off the mark when placed in front of a mirror. Animals that pass this test include chimps, bonobos, orangutans, Asian elephants, Eurasian magpies, whales and dolphins (which inspect rather than scrub off the mark). Gorillas and rhesus macaques usually fail the test. Humans recognise themselves in a mirror by the age of three.

Recent findings have challenged whether the mirror test measures self-awareness, or the ability to learn self-awareness. In 2017, Liangtang Chang, a researcher at the Shanghai Institutes for Biological Sciences, China, and his colleagues trained rhesus macaques to recognise themselves in a mirror.14 To do this, they gave the monkeys a food reward for touching a red laser dot projected onto a surface in the monkeys’ vicinity. At first the laser was shone directly in front of the monkeys, where they could easily spot it. Then, it was shone on an area that could only be seen through a mirror. Following several weeks of such training, the researchers started moving the laser dot to the monkeys’ face. And voilà! They suddenly realised that the red dot on the face in the mirror was pointing to their own. They had learned self-awareness.

After their training, the monkeys were filmed exploring their newly discovered skill, inspecting their facial hair and fingertips, investigating previously unseen body parts and playfully flashing their genitals. The video footage leaves little doubt: they are completely hooked on themselves, enthralled by their own existence. ‘Clever studies like the one by Chang [and colleagues],’ wrote a group of fellow researchers, ‘help expose our preconceptions about ourselves and point the way toward a deeper understanding of the way our brains, and the brains of other animals, construct reality and our place within it.’15 That deeper understanding is twofold: it suggests that other species have at least one sense of self, and that the social construction of the self means that self-awareness can be taught.

There are good reasons why our minds evolved this way. The brain is constantly building models of the world around us. For early humans, life in tight-knit communities meant they probably only needed to construct a few mental selves to survive and reproduce. Gradually, as social groups grew larger and more complex, each individual member of Homo sapiens needed to construct multiple selves in order to adapt to the new social system.

The notion of a unified self is not only an illusion but a dangerous one. By rejecting the diversity of ways it is possible to live in the world, the unitary self inhibits mutual respect and social justice. Importantly, it’s now well-established that our attachment to the unified self can cause bullying, selfishness, and greed, which sometimes tips into narcissistic personality disorder (NPD): a mental health condition characterised by arrogant thinking, lack of empathy and an inflated sense of importance.16 Individual rights are vital for a free society, no doubt; but to become a moral society we must be more open-minded about the community of selves we each are.

Because the truth is, the self isn’t one thing. It’s a spectacular profusion of things – it’s the social self, the solitary self, the loving self, the caring-for-the-environment self, the learning-something-new self. There is no owner, no core self. Nothing about us is centralised. We are each a multiplicity of ever-changing, reinvented, redefined selves. The French philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau vividly captured this astonishing revelation in his Confessions:

I have very intense passions, and while I am in their grip my impetuousness is without equal: I know neither restraint, nor respect, nor fear, nor decorum; I am cynical, insolent, violent, bold: there is no shame that could stop me, nor danger that could frighten me: beyond the one object that occupies me, the universe is nothing to me. But all that lasts only a moment, and the moment that follows annihilates me.17

Free Will

The realisation that our brains evolved to conjure up illusions and multiple selves leaves a big question to be answered: are we free? Is what we do a choice freely made or the result of inevitable computations? The classic problem of free will is one of the most misunderstood in all of neuroscience. For centuries, theologians and natural philosophers have been at loggerheads over the nature and significance of free will. It’s a debate that’s filled every period of world history and been taken up by every intellectual figure since the dawn of our species.

Plato believed that free will is entirely based on our knowledge of good and evil: the person who strives for good in the form of wisdom, courage and temperance is truly free, while the person who abstains from such virtues and seeks pleasure and passion alone is a slave. It became known as ethical determinism – or ‘moral liberty’ in the Christian tradition – and has been discussed by philosophers of all persuasions. Another Greek giant, Aristotle, took things further by arguing that good choices lead to good habits, which in turn lead to good character. Like Plato, he believed that humans can freely choose between right and wrong, but he placed more emphasis on free will being something earned as a result of good character.

The idea that human choices may be partly or wholly determined by natural forces beyond our control was first put forward by the Stoics, a school of philosophy founded by Zeno of Citium, in Athens, in the early third century BC. Zeno and his disciples believed that everything in the universe and all human behaviour is causally determined by the laws of science. They still believed that our choices can be freely made – life presents us with options and we can clearly see that those options have their own consequences. We still therefore have a moral responsibility to make good choices.

The Stoics had their critics. Among them was the philosopher Alexander of Aphrodisias, who, in his work On Fate, argued against any earthly influence on human action. Shortly after this, monotheistic theologians including Saint Augustine of Hippo (354–430), Al-Ash’ari (874–936) and Maimonides (1138–1204) used religious dogma rather than reason to understand free will. It was the Enlightenment philosophers such as Thomas Hobbes (1588–1679), David Hume (1711–76) and Immanuel Kant (1724–1804) who reaffirmed that free will was written in the clockwork laws of nature.

Since then, modern conceptions of free will have focused on evolution and the inner workings of the brain. Just as the firing of neurons determines our thoughts, memories and dreams, so too do they govern our choices, behaviour and sense of free will. Nowhere is this more evident than in cases of ordinary people who become killers or rapists after suffering from brain tumours that fundamentally alter their brain chemistry. As unsettling as it may seem, these people no more choose their actions than a hurricane chooses to destroy a building. The same rubric applies to healthy people, as well. Were we to understand the brain better than we currently do, we could predict a person’s future behaviour with astonishing accuracy.

This brings us to science’s most up-to-date understanding of free will: you have free will, you just don’t have conscious will. How do we know this? Well, as far back as the late 1980s, an American neuroscientist named Benjamin Libet conducted a series of experiments which revealed that we become consciously aware of a decision about half a second after the brain has directed the neural mechanisms responsible for the decision.18 Think for a moment how strange this is. In our daily lives we experience freely made choices as being willed into existence: we consider the options before us, deliberate over which is best and, then, as with a muscle, we consciously ‘flex’ our choice into the world. Half a second is quite a long time. Wouldn’t we notice such a delay?

The answer is no because, as we have seen, there is no distinct and separate self in the first place. It merely feels like we have made the decision when in fact the brain has already made it for us. You can begin to grasp this with an easy experiment. Take a moment to give yourself a simple choice. It can be anything – clapping your hands, lifting your leg, turning your head – but the choice must be made every twenty seconds. Repeat this for a few minutes, closely observing the experience and how it feels. Think of nothing else besides the choice and how it is being made. Can you tell how the choice is being made? Are you choosing when to choose, or is the choice just appearing in your consciousness? Does consciousness deliver the choice to you, or does the choice seem to arrive from nowhere? What made you choose to clap or not to clap? When you really think about it, you realise that ‘you’ – the self – had absolutely nothing to do with it.19

Some researchers think that half a second is underestimating the time it takes for our brains to make decisions. In 2008, a group at the Max Planck Institute for Human Cognitive and Brain Sciences in Leipzig, Germany, conducted brain scans on fourteen people while they performed a decision-making task.20 They were asked simply to press a button with their left or right hand whenever they felt like it. When the team analysed the data, they detected a brain signal more than seven seconds before the volunteers claimed to have made their decision. Seven seconds is a lifetime to the brain. To put that in context, it took the world’s most powerful supercomputer forty minutes to simulate just one second of brain activity.21

For the brain, the events taking place in that gulf of time are practically infinite. What’s happening in those dark seven seconds is anyone’s guess. The only thing the researchers spotted was a shift in brain activity from the frontopolar cortex (a region linked to planning) to the parietal cortex (a region linked to movement), which isn’t a great deal to go on. But as the study’s lead author John Dylan Haynes comments, the implications are clear: ‘there’s not much space for free will to operate.’

As with consciousness, the illusion of free will is a result of evolution. But how and why would evolution generate something so complex and deceptive? The answer to ‘how’ is easy: as another product of the brain, the free will illusion consists of the billions of neurons that evolution has built for us. No single neuron or brain region has free will, of course; not even the famous neurosurgeon Henry Marsh could find a piece of brain tissue that knows or cares who we are. But like much in the brain, the origin of free will is to be found in the cohesive whole and not its constituent parts.

The answer to ‘why’ isn’t so straightforward, but a great deal of evidence suggests that while free will is an illusion created by our brain, we are better off believing we have it anyway. People who believe that they have control of their actions are happier, less stressed, less likely to steal, less likely to cheat in an exam, more creative, more humble, more grateful, more committed to relationships, more likely to work hard and show up for work on time and more likely to give money to the homeless.22

Amazingly, the illusion of free will can be triggered in people. In 1999 the psychologists Daniel Wegner and Thalia Wheatley performed experiments based on the concept of the Ouija board.23 The only spirit being contacted in this version, however, was the everyday illusion of human agency. In the experiment, two participants were asked to move a board resting on top of a computer mouse, with the mouse moving a cursor over various pictures on a computer screen. One participant was then asked to force the other to land on a particular picture, a little like cheating on a Ouija board. Each participant was wearing headphones, through which they would hear the name of the picture at different time intervals: either slightly before or slightly after they are forced to move the cursor.

Just as on a Ouija board, it’s obvious when the other participant is forcing the move. However, if the name of the object is played a second before the participant is forced to move the cursor, she or he will claim to have done it themselves. It’s that easy to be fooled. Wegner calls this the mind’s best trick. Despite walking around with the day-to-day certainty that we consciously control our behaviour, it just isn’t so. The feeling of free will, he says, merely ‘arises from interpreting one’s thought as the cause of the act.’

Viewed in this way, human choice is more delicate and mysterious than we ever imagined. Silently cocooned in an illusory exterior, hidden in depths that may forever lie beyond our grasp, our choices emerge like dark matter in the cosmos. They affect everything we hold dear: our laws, our politics and our sense of moral responsibility. The fact that human minds evolved over millions of years by chance does not diminish their value. Our lives, as William James declared, are ‘not the dull rattling off of a chain that was forged innumerable ages ago.’ Perhaps, then, the most precious gift we have inherited from our brain’s evolutionary journey is that we are all born free.