Lt. Cdr. E. Boyle

The sea was calm and the night dark as HM Submarine E14 twisted between the myriad craft anchored off Cape Helles on her passage up the Dardanelles. It was around 3.00 a.m. on 27 April. Barely an hour and a half had passed since Lt. Cdr. Courtney Boyle had slipped out of Tenedos at the start of his mission to break through the Narrows into the Sea of Marmora, for so long regarded by the Turks as their own private lake.

As the E14 passed the ruined fortress of Sedd el Bahr, the sounds of conflict drifted eerily across the water; the rattle of rifle fire mingling with the cries of men, fighting on the bitterly contested beachhead. Boyle, standing alone and exposed on the open conning-tower, could hear it all. The canvas bridge screen had been removed and all the steel stanchions taken down save one, to give him something to hold on to while navigating a course along the surface.

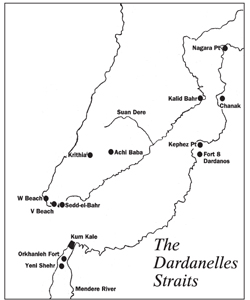

Occasionally, the night sky was lit by red flashes as the heavy guns from the French battleships thundered across the anchorage. Dead ahead, some eight miles distant, lay the Narrows, bathed in brilliant white light, like a vast stage, while still closer, at the mouth of the Suan Dere river, a single powerful searchlight swept across the water. There was a strange air of unreality. To Boyle’s first lieutenant, Edward Stanley, ‘it all looked very weird and threatening’. Positioned just below the open conning-tower hatch, Stanley passed Boyle’s orders on to the coxswain at the foot of the ladder. He was also in charge of the submarine’s gyro compass, a new and important navigational aid considered to require such careful handling that no one else, not even the captain, was allowed to touch it.

Such rules were typical of the meticulous planning which had gone into Boyle’s preparation for the hazardous venture into one of the world’s most heavily defended stretches of water. Since December 1914, when the small submarine B11, commanded by Lt. Norman Holbrook, ventured half-way up the Narrows to sink an old Turkish battleship below Chanak, three submarines had dared to reach the Sea of Marmora. Two had been sunk and only one, the AE2, an Australian submarine commanded by an Irishman, had successfully negotiated the Dardanelles. Lt. Cdr. Hew Stoker’s foray on 25 April signalled the start of one of the most daring and successful submarine campaigns ever to be waged. But her entry into the Sea of Marmora was of little practical assistance to Boyle, who knew nothing of her experiences. The success or failure of the E14’s passage, therefore, would rest wholly on his own plan, based on personal experience and reconnaissances of the approaches to the Dardanelles. Lt. Stanley later noted:

There was very little guessing … as far as possible everything which could ensure success was thought of in advance. The battery was brought up to 100% condition and an hour before starting off was ‘fizzing’, then ventilated, left topped until within half an hour of diving. Every tank, blow and motor had been examined – all was in tip top condition.

The route through the Narrows

Even with such a high degree of planning, however, there was much that was not known about the obstacles confronting them. As well as at least five rows of mines and numerous vessels patrolling the Narrows, there were reports of shore-sited torpedo tubes, a sunken bridge off Nagara Point and anti-submarine nets. These posed formidable enough problems, but when combined with the natural elements they appeared almost insurmountable. Although the E-class boats were designed to stay submerged for 50 miles, the power of the current, running at 3–5 knots through the narrow bottle-neck linking the Sea of Marmora to the Mediterranean, made it unlikely they would be able to complete the tortuous passage of the 35-mile-long Straits underwater. Nor could they be sure of avoiding all of the moored mines by diving deep. To safely navigate, it was vital to take frequent observations of landmarks which necessarily entailed operating at periscope depth. Even had they been able to remain submerged, the navigation of such a confined waterway dominated by strong-running currents represented one of the most dangerous challenges then known to submariners. In addition, they faced the hazards posed by the change of water density as the saltwater of the Mediterranean met the freshwater of the Marmora, which could make submarines almost uncontrollable.

It was scarcely surprising, therefore, that when originally asked whether an E-boat could make it through to the Marmora, Boyle had sided with the majority of senior naval officers in delivering a firm ‘No’. Only the commander of the E15 had thought it possible, and his attempt resulted in the second submarine loss of the campaign. Since then the AE2 had shown the way, and now it was E14’s turn. As the submarine entered the Straits, Lt. Stanley noted ‘the crew were extremely calm’. There was no sign of excitement. ‘I think really that we were all resigned for the worst and hoped for the best’, he added.

At about 4.00 a.m. the E14 was caught in the glare of the searchlight at Suan Dere and almost immediately shells splashed into the sea ahead. Boyle took this as his cue to submerge. In his official report he recorded:

Dived to 90 feet under the minefield. Rose to 22 feet 1 mile south of Killid Bahr and at 5.15 a.m. passed Chanak, all the forts firing at me. There were a lot of small ships and steamboats patrolling, and I saw one torpedo gunboat, ‘Berki-Satvet’ class, which I fired at, range about 1,600 yards. I just had time to see a large column of water as high as her mast rise from her quarter where she was presumably hit, when I had to dip again as the men in a small steam boat were leaning over trying to catch hold of the top of my periscope.

It was an extraordinary encounter. Boyle had, in fact, sunk the Turkish gunboat with his second torpedo, but he was fortunate to have escaped without damage from his brush with the steamboat crew. Rounding Nagara Point at 6.30 a.m., he passed beneath a succession of small craft apparently searching for him. At 9.00 a.m., while coming up to periscope depth to get a navigational fix, he spotted a Turkish battleship less than a mile astern, but decided to ignore her and press on towards the Sea of Marmora, which he entered at 10.15 a.m. Boyle was able to observe Turkish efforts to locate him, but not wishing to give his position away, he spent much of his first day submerged. The next day proved a frustrating one with a succession of Turkish patrol craft forcing the E14 to dive whenever the submarine came to the surface to charge her over-worked batteries. Boyle decided to seek out a safer hunting ground, and later that evening moved along the surface to the north-east of Marmora Island.

The next day, 29 April, he spotted a convoy of two troopships escorted by three destroyers. Conditions for attack, however, were far from ideal. He reported:

Unfortunately, it was a glassy calm and the TBDs [destroyers] sighted my periscope and came for me and opened fire while I was a good way off. I fired at one transport, range about 1,500 yards, but had to dip before I could see the effect of the shot. (One periscope had had the upper window pane broken by a shot the day before and was useless, and so I could not afford to risk my remaining one being bent).

According to Turkish records, one of the escorting destroyers, probably the Muavent-I Milliye, made a vain attempt to ram E14. Half an hour later, when Boyle felt it safe enough to come to periscope depth, he observed that the destroyers were escorting only one troopship and the other, later identified as the 921-ton steamer Ittihat, was ‘making for the shore at Sar Kioi with dense columns of yellow smoke pouring from her’.

Later that afternoon the E14 made an unscheduled meeting with AE2, and plans were made for another rendezvous the next day. But Stoker’s submarine was sunk the following morning, before she could keep her appointment. The next day the Turks celebrated another success, the destruction of the French submarine Joule while attempting to break through the Straits. The crew of E14 would have to continue their efforts alone.

Boyle, meanwhile, was determined to adopt a more aggressive approach towards his most persistent adversaries. As he said in his report: ‘I decided to sink a patrol ship as they were always firing at me.’ He found his victim at 10.45 a.m. on 1 May, and made short work of it. One torpedo was enough to send the Turkish minelayer Nour-el-Bahr to the bottom. Leading Stoker John Haskins wrote in his diary:

The Captain saw two men aboard the mine-layer, cleaning a gun abaft; they saw the torpedo coming straight at them, and they started to run to tell the officer on the bridge. But they were too late. The torpedo hit her and she blew up. By the explosion she made, she must have been full of mines. There was nothing left of her in three minutes. The blast gave us a good shaking up, but nobody minded, as it meant another enemy ship less.

Boyle’s reputation was growing rapidly, both among his own crew and the Turks, who attempted to counter the submarine menace by establishing a primitive coast-watching network. Bonfires were lit along the shore as warnings to shipping whenever sightings were made. However, it was bad luck and not smoke signals which denied Boyle of further success on 5 May. On that date, he carried out a textbook attack on a Turkish transport, but his torpedo, which was seen to strike the target, failed to explode. The Turks were becoming increasingly wary. The next day a destroyer and transport turned and fled back towards Constantinople at the sight of E14. Boyle added to their timidity on 8 May when, having stopped and searched two vessels crowded with refugees, he followed a third steamer into the Turkish harbour at Rodosto. He reported: ‘She anchored close in shore and was also full of refugees. Approached within 1,200 yards of the shore. I could not see any troops, but they opened a heavy rifle fire on us, hitting the boat several times, so I went away.’

Two days later the E14 surfaced near Kalolimno Island. The sea was clear and Boyle decided to allow the crew some relaxation. But while they were taking a swim, a destroyer hove into view. Leading Stoker Haskins noted: ‘There was a hell of a splash as the lads climbed aboard and stood by their diving stations.’

Boyle took E14 down and the destroyer passed directly above. Half an hour later, Boyle sighted two transports being escorted by a single destroyer. In what would prove to be his greatest success of a profitable first patrol in the Marmora, he immediately attacked:

The torpedo fired at the leading transport did not run straight and missed astern. The second torpedo hit the second transport, and there was a terrific explosion. Debris and men were seen falling into the water … Unfortunately it was 7.35 p.m. when I fired, and in ten minutes it was quite dark, so I did not see her actually sink. However, she was very much down by the stern when I last saw her, and must have sunk in a very short time.

The crew of the E14 were jubilant. Haskins wrote: ‘The lads gave a cheer as the troops aboard the transport jumped overboard in their hundreds.’

What Boyle, in his report, described as a three-masted and two-funnelled ship ‘twice as large as any other ship I saw there’, was, in fact, the 5,017-ton former White Star liner Germanic, rechristened Guj Djemal. And, contrary to his supposition as to the vessel’s fate, she appears to have survived the encounter, though her bows had been broken. According to Turkish records, the Guj Djemal, which was carrying 1,600 troops (British accounts speak of 6,000 men and an artillery battery), was able to limp into Constantinople with the assistance of two Bosphorus ferries.

The torpedo attack, on the thirteenth day of the E14’s patrol, was to be her last. Boyle had expended nine of his ten torpedoes; the remaining one was found to be faulty. Of the nine, four had resulted in the destruction of a gunboat, minelayer and transport and the almost certain loss of a second transport. Three had either not run true or failed to explode and only two had missed their targets. It was an impressive success rate. Boyle’s achievements, however, went far beyond material destruction. Turkish shipping movements were severely disrupted, seriously hampering the transport of men and material to the peninsula. But the impact on civilian morale was even greater. Such was the extent of the hysteria gripping Constantinople, it was considered that the continued presence of the E14 in the Sea of Marmora, even without offensive armament, would contribute significantly to the weakening of Turkish resolve. It appeared to be an accurate assumption. On 13 May the unarmed E14 chased a small steamer with such determination that she ran herself aground. A brief rifle skirmish followed before Boyle left her and headed for Erekli Bay.

The next morning, Boyle decided to employ a new ‘weapon’ – deception. A dummy gun was rigged up, and was immediately used to help stop a Turkish tug towing a lighter. After an inspection revealed the cargo to be baulks of timber, she was allowed to continue, although reports of her interception could only have served to fuel Turkish anxieties. Later Boyle suffered the frustration of having to allow a convoy consisting of three full transports and one destroyer to pass because of his lack of torpedoes. A busy day ended with the E14 narrowly avoiding disaster after failing to spot a Turkish patrol boat until it was almost too late. Leading Stoker Haskins recorded: ‘At 9.10 we had to dive in a hurry. It was very dark, and before we knew what was happening an enemy destroyer appeared right on top of us. It was a near thing.’ According to Boyle, the destroyer which almost caught them napping on the surface was ‘not more than 400 yards off when sighted’. It was not the first time that the Turks had been in with a chance of catching their quarry, and Boyle was convinced that only their lack of determination spared his vessel from destruction. He noted:

I think that the Turkish torpedo boats must have been frightened of ramming us, as several times when I tried to remain on the surface at night, they were so close when sighted that it must have been possible to get us if they had so desired. In the day time the atmosphere was so clear that we were practically always in sight from the shore, and these signal fires and smoke columns were always in evidence, so I think our position was always known to the patrols unless we dived most of the day.

By 16 May provisions were running low and water was rationed to one pint per man a day. There were hopes that the submarine would be resupplied by the E11, but the following day E14 was ordered by wireless to return. On the morning of 18 May, the twenty-first day of his momentous patrol, Boyle brought his boat out of the Dardanelles. Despite having been detected at the very outset of his return trip, and again by the Turkish shore defences at Chanak, he skilfully avoided all obstacles to complete the first double passage. The E14 surfaced close to a French battleship, its decks crowded with cheering sailors. With a destroyer as escort, the submarine, sporting the ‘Jolly Roger’, entered Kephalo where, according to Haskins, ‘we had to go around the whole fleet and they certainly gave us a cheer’.

It had been an outstandingly successful patrol, far exceeding his superiors’ hopes. As early as 14 May, Cdre. Roger Keyes had wired the Admiralty praising Boyle and outlining his record of success. Although no official recommendation for honours was made, Keyes had insisted that Boyle ‘deserved the greatest credit for his persistent enterprise in remaining in the Sea of Marmora, hunted day and night …’. In a subsequent telegraph, Vice-Admiral de Robeck stated: ‘It is impossible to do full justice to this great achievement.’ The result was one of the swiftest announcements of a VC after the action for which it was gained. News of the honour reached the Mediterranean Fleet on 19 May, two days before it was officially recorded in the London Gazette and before Boyle had compiled his own report. Even Keyes was astonished at the speed of events. ‘I was hoping they would give him a VC but rather doubted it’, he wrote to his wife. ‘That they should have done so without our official recommendation was splendid.’ In his diary entry for 19 May, Leading Stoker Haskins recorded:

At 6.30 a.m. all hands were turned out and had to fall in on the boat. And then, reading out the citations, they inform[ed] us that our Captain had been awarded the VC and that our second and third officers had been awarded the DSC and that the remainder of the crew had been awarded the DSM each. We gave three cheers for our officers and then at 11.20 a.m. we got on the way for Mudros …

For his part, Boyle heaped praise on his crew. He credited much of the E14’s success to the ‘untiring energy, knowledge of the boat, and general efficiency’ of his first lieutenant, Lt. Stanley, and acknowledged the intelligent hard work of his navigator, Acting Lt. Reginald Lawrence, RNR. He also selected for special mention five senior crew members, including Leading Stoker Haskins. His own Victoria Cross citation read:

For most conspicuous bravery, in command of Submarine E14, when he dived his vessel under the enemy’s minefields and entered the Sea of Marmora on the 27th April, 1915. In spite of great navigational difficulties from strong currents, of the continual neighbourhood of hostile patrols, and of the hourly danger of attack from the enemy, he continued to operate in the narrow waters of the Straits and succeeded in sinking two Turkish gunboats and one large military transport.

![]()

Edward Courtney Boyle, one of the most distinguished submariners of his generation, was born on 23 March 1883 in Carlisle, Cumberland, the son of Lt. Col. Edward Boyle, then serving in the Army Pay Department, and Edith (née Cowley).

Educated at Cheltenham College, he entered HMS Britannia in 1897 and became a midshipman the following year. He was an early convert to one of the Navy’s newest branches, the Submarine Service. His abilities were such that he was given his first command, a Holland boat, as a 21-year-old sub-lieutenant.

Attractive and intelligent, if somewhat reserved, Boyle’s behaviour suggested a casual indifference which was sometimes mistaken for arrogance. To some of his colleagues he gave the impression of being bored by life in the peacetime Navy. Appearances, however, were deceptive. The long-limbed Boyle was one of those rare individuals who could accomplish with relative ease and unruffled calm what others strained to achieve. Charles Brodie, a fellow submariner in the pre-war days, remembered:

In the period 1905–8 submarines and motor bicycles were new and fascinating if grubby toys, and specialists in both were often dubbed pirates. Boyle knew his submarine as thoroughly and rode his motor bicycle as fast as any, but was more courteous and tidy than most pirates … He did not pose, but seemed slightly aloof, ganging his own gait.

His quiet authority and cool efficiency in handling submarines was duly noted. Promotion followed at regular intervals, and a succession of submarine commands followed. At the outbreak of war he was captaining D3 in the 8th Submarine Flotilla. His early North Sea patrols, which included what Keyes described as a ‘first class daring reconnaissance’ into the shoals inside the Amrum Bank off the north German coast, were recognised by the award of a mention in dispatches. As a further reward, Boyle was promoted lieutenant commander and given command of the E14, one of the Navy’s latest submarines. The following March, E14 was among three E-class boats sent from England to operate in the Dardanelles. It would prove to be a happy hunting ground for the modest yet quietly confident Boyle.

Between April and August Boyle and E14 completed three successful cruises into the Sea of Marmora, each journey through the Dardanelles made more dangerous than the previous one by the ever-strengthened Turkish defences. During the return passage at the end of his third patrol, the E14 came perilously close to disaster. Having burst through a new anti-submarine net, she narrowly escaped being hit by two torpedoes fired from the shore, before scraping her way through the Turkish minefields to safety. Perhaps it was an omen. The E14 and her captain were withdrawn from the fray and given a well-earned rest.

In all, Boyle had spent seventy days in the Marmora, and as well as enduring the prolonged strain of command in hostile waters, he had, like many of his crew, suffered bouts of dysentery and illness. The Royal Navy recognised his services by promoting him to commander, while Britain’s allies showered him with decorations. The French made him a Chevalier of the Legion of Honour and the Italians gave him their Order of St Maurice and St Lazarus. But apart from the VC given for his first patrol, Boyle surprisingly received no further awards from his own country.

He continued to serve in submarines. By 1917 he was once more operating in the North Sea, in command of the new boat J5, in a flotilla which included the Navy’s Baltic ace, Cdr. Max Horton, DSO and Bar. There were, however, reminders of his Dardanelles days. That same year, Boyle fought and lost a £31,000 ‘blood money’ claim in an Admiralty prize court for the ‘sinking’ of the Guj Djemal. Ironically, the grounds for refusing him were not that the ship had survived the attack – so far as the Royal Navy was concerned, it had been destroyed – but that it was not ‘offensively armed’. Some months after the war, however, the Admiralty, still apparently none the wiser as to the true fate of the vessel, reversed their decision.

The end of the war found him in command of the Australian Submarine Flotilla. Two years later he was promoted captain.

During the next ten years, Boyle alternated sea-going commands with shore duties. He commanded, in turn, the cruisers HMS Birmingham and Carysfort and the aging battleship Iron Duke, while for two years he served as King’s Harbour Master at Devonport. Promoted rear-admiral in October 1932, he retired on a Good Service Pension. During the Second World War he served for a time as flag officer in charge, London.

In an active retirement, Rear-Admiral Boyle, a childless widower who lived at Sunningdale Hotel, became an enthusiastic member of the local golf club. He died on 16 December 1967, as a result of injuries sustained the previous day when he was knocked down by a lorry on a pedestrian crossing.

Twenty-one years later, members of the Boyle family provided a fitting epitaph to the life of one of the Navy’s most gifted pioneer submariners, when they presented their heroic forebear’s Victoria Cross to HMS Dolphin, headquarters of the 1st Submarine Squadron at Gosport.