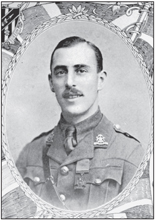

Lt. W. Forshaw

It had been a quiet day on the Helles front; ominously so, in the opinion of 25-year-old William Forshaw, a subaltern serving with the 9th Manchesters. A schoolteacher by profession, the young Territorial officer had been on the peninsula for barely a fortnight. Yet already the spirit of optimism was beginning to fade. As far as 2nd Lt. Forshaw was concerned the portents did not appear good. Writing to his former headmaster on 21 May, he confided:

I think I can safely say that it is a much stiffer proposition than was first anticipated. This country was made for defence – every inch of it – and the enemy are exceedingly well led. They are making the most of their natural advantages. Man for man, or even regimentally, they cannot compare with us, but their generals are good… . They are giving nothing away.

Over the succeeding weeks, the experience of the British forces at Helles would bear out his words. Three large-scale attacks, launched on 4 June, 28 June and 12 July, advanced the Allied lines by the merest of margins at a cost in lives which was impossible to sustain without far greater reinforcements. Trenches criss-crossed the southern neck of the peninsula, turning the Turkish position into a veritable stronghold. Such was the stalemate at Helles by the first week in August, the southern sector had become a virtual sideshow. Attention had swung north to Suvla Bay for the opening of a new front and a fresh effort to outflank the Turks.

It was in an attempt to ensure the success of the northern operations that the 42nd East Lancashire Division, which included among its units the 9th Manchesters, undertook the last major British offensive to be mounted south of Achi Baba. What was conceived as a diversionary attack, designed to draw Turkish reserves away from the main thrust, began at 3.50 p.m. on 6 August, some seven hours before transports began disgorging men and materials on to the darkened beaches of Suvla Bay. The Helles feint, launched by the reconstructed 88th Brigade of the 29th Division and continued by the 125th and 127th Brigades of the 42nd East Lancashire Division, was directed at a small kink in the Turkish lines straddling the two forks of the Kirte Dere. According to the optimistic and frighteningly simplistic plan, the assault battalions would slice through the northern face of the salient, capturing the frontline trench known as H13, leaving the Lancastrians to follow up the next day with an attack on the southern half of the Turkish lines, where they bisected a small vineyard to the west of the Krithia road.

The Turks, however, had long suspected a British attack at this point and were well prepared. When the woefully inadequate British bombardment subsided, they were ready and waiting for the assault. In the furious battle which followed, the leading waves were all but annihilated. A few parties bludgeoned their way into the Turkish trenches only to be slaughtered or compelled to retreat. In the confusion, orders for further attacks were given and then countermanded. Of the 3,000 British engaged, approximately 2,000 had become casualties and the 88th Brigade had almost ceased to exist as a fighting entity. The frontline trenches were clogged with wounded and shocked survivors. It had been a day of unmitigated disaster.

Yet despite the failure of the northern assault and the realization that the Turkish defences had been fatally under-estimated, the attack on the southern portion of the salient was not cancelled. The two-brigade attack, launched at 9.40 a.m. on 7 August, was made on a frontage of 800 yds with the objective of capturing and securing the main Turkish support line, F13–H11b. To reach it, the men of the 42nd East Lancashire Division would have to struggle through a labyrinth of trenches in one of the most intricately fortified sectors of the Turkish lines. It was scarcely a surprise, in view of the events of the preceding day, that the attack was bloodily repulsed at every point, save for the small vineyard on the right of the salient. Here fragments of the 6th and 7th Lancashire Fusiliers clung to their hard-won gains. By midday this pocket of resistance, a salient within a salient, was all the 42nd Division had to show for its endeavours. Military logic dictated a withdrawal from what appeared an untenable position. However, it was held not for reasons of strategic importance but on a point of principle. The Vineyard had become a symbol of stubborn pride.

During the afternoon, the remnants of the Lancashire Fusiliers were bolstered by the arrival of two platoons from A Company, the 9th Manchesters, otherwise known as ‘Ashton’s Own’. They were led by the same William Forshaw, who ten weeks earlier had so perceptively judged the Turkish powers of resistance. Now his own resolve would be put to the test.

Since arriving on the peninsula, the 9th Manchesters had escaped the worst of the fighting and their losses were correspondingly light. Forshaw had been promoted from quartermaster to the command of A Company, with the temporary rank of captain, shortly before the battle in which the 9th were held in reserve. His second in command was 2nd Lt. C.E. Cooke. For them, and for most of their men, the advance into the Vineyard represented a violent introduction to trench warfare.

Passing over the newly captured ground, they were guided to the north-western corner of the position, at the vital junction of the former Turkish trench, G12. Both sides knew it to be the key to the precarious British incursion. All that separated Briton from Turk at this point were hastily constructed barricades. To hold his post Forshaw had approximately twenty men armed with rifles and a plentiful supply of jam-tin bombs. Forshaw put the number of bombs at around 800 and, in the absence of machine-guns, saw in them his best chance of salvation. He later recalled:

We decided that we would hold on to the position whatever it cost us, for we knew what it meant to us. If we had lost it the whole of the trench would have fallen into the hands of the enemy. I had half of the men with me, and the other half I placed along the trench with a subaltern [2nd Lt. Cooke].

Three Turkish-held saps converged on Forshaw’s post, and it was from these that the Turks hurled themselves in a series of frenzied assaults beginning on the night of 7 August and continuing until the morning of 9 August. The close-quarter fighting was of almost medieval savagery. Seventy years later, Godfrey Clay, a member of Forshaw’s force, remembered: ‘We hadn’t been in above half an hour when the Turks got out over the top and came at us … We kept them out … How I don’t know. Mostly with rifle fire … I got a bullet through my hair that day.’ Another of the defenders, Sgt. Harry Grantham, who had earned a DCM a month earlier, stated: ‘We could see the Turks coming on at us, great big fellows they were, and we dropped our bombs right amidst them.’ Forshaw was the life and soul of the defence. Wherever the fighting was most intense he was to be found, hurling bombs and shouting encouragement to his men. According to Sgt. Grantham:

He fairly revelled in it. He kept joking and cheering us on and was smoking cigarettes all the while. He used his cigarettes to light the fuses of the bombs, instead of striking matches. ‘Keep it up, boys’, he kept saying. We did, although a lot of our lads were killed and injured by the Turkish fire bombs [sic].

Forshaw later explained: ‘I was far too busy to think of myself or even to think of anything. We just went at it without a pause while the Turks were attacking, and in the slack intervals I put more fuses into bombs.’

In a brief lull in the fighting on the first night, Forshaw was surprised to see a young Turkish officer peering over the parapet with his hands above his head. ‘He seemed perfectly dazed and we took him prisoner’, said Forshaw. During the next day, Forshaw’s dwindling force beat off further attacks in which Cpl. S. Bayley and L/Cpl. T. Pickford figured prominently. After twenty-four hours of near continuous fighting without sleep or food and water, they were finally relieved by a detachment drawn from other battalions in the Division. As most of his men marched out of the Vineyard, Forshaw, together with Cpl. Bayley, volunteered to remain, and it was during their second night in the position that the Turks mounted their most determined counter-attack. Three times they threw themselves forward. Twice they were halted before reaching the parapet, but on one occasion they burst in. As they clambered over the barricade and dropped into the darkened trench they were met, almost inevitably, by Forshaw. He recalled:

Three of these big, dark-skinned warriors appeared. Immediately one made a move for a corporal who was digging a hole from which to fire during the night. I saw the Turk make for him with his long bayonet and I straight away put a bullet through him from my useful Colt revolver. My weapon was a very fine friend to me during those thrilling minutes. A second Turk came for me with his bayonet fixed, evidently with the object of covering his pal, who was making for the box of our bombs, but I managed to put them both out of action. They never came over the parapet again; but, realising as they did what the position meant, they kept up a fusilade during the whole night.

The crisis had passed, but the relentless pressure of the past two days’ action had taken their toll on even Forshaw’s powers of resistance. At 9.00 a.m. on 9 August he was relieved by 2nd Lt. Cooke and made his way back to battalion HQ. According to the unit war diary, he was ‘quite done up and covered with bomb fumes. He had been hit by a shrapnel case and had been fighting for two days and nights without ceasing.’ His courageous and energetic defence of the most exposed post made a deep impact on his comrades. The 9th Manchesters’ war diary recorded:

He had shown extraordinary bravery and had by his personal example been the cause of the Vineyard trenches G12 being retained by us … The Brigadier-General of the 126th Brigade personally congratulated the commanding officer on the gallant behaviour of Lieut Forshaw, Second Lieut Cooke and the two platoons under them.

For some days after the action, Forshaw was unable to speak; the combination of shouting and smoking cigarettes had left him voiceless. Sick from the stench of bomb fumes and suffering from shock, he was nevertheless incredulous at his survival. ‘I cannot imagine how I escaped with only a bruise’, he later said. ‘It was miraculous.’ A few weeks after the battle, he stated:

It was like a big game. I knew it was risky, of course, but in the excitement one loses all sense of personal danger. You get frightfully excited, and I think it was the excitement that held me up. You see men knocked out, dead and dying, all around you, but it doesn’t trouble you in the least, except when you see good men and chums hit you feel determined to have revenge. That was why I volunteered to keep on after being relieved.

That the fighting left psychological scars, however, was clearly evident. Cpl. Bayley, who had fought alongside Forshaw during the two-day battle, wrote to his sister on 16 August:

Myself and a few men and the captain held a trench which was almost impossible to hold, but we stuck it like glue, in spite of the Turks attacking us with bombs … Our captain has been recommended for the VC and I hope he gets it, because he was determined to hold the trench till the last man was finished. But we did not lose many. Our captain has not got over it yet, but it is only his nerves that are shattered a bit …

Forshaw was evacuated to Cairo ‘suffering from shock’, and from there he cabled his parents: ‘Not wounded. Nearly fit again.’ While convalescing news reached him on 9 September that he had been awarded the Victoria Cross. The citation read:

For most conspicuous bravery and determination on the Gallipoli Peninsula from 7th to 9th August, 1915.

When holding the north-west corner of the ‘Vineyard’ he was attacked and heavily bombed by Turks, who advanced time after time by three trenches which converged at this point; but he held his own, not only directing his men and encouraging them by exposing himself with the utmost disregard to danger, but personally throwing bombs continuously for 41 hours.

When his detachment was relieved after 24 hours he volunteered to continue the direction of operations.

Three times during the night of 8th–9th August he was again heavily attacked, and once the Turks got over the barricade, but after shooting three with his revolver he led his men forward, and captured it.

When he rejoined his battalion he was choked and sickened by bomb fumes, badly bruised by a fragment of shrapnel, and could hardly lift his arm from continuous bomb throwing.

It was due to his personal example, magnificent courage and endurance that this very important corner was held.

It was the first VC to go to a member of the 42nd Division and letters of congratulation poured in. As well as Forshaw’s award, there were decorations for other members of his gallant company. 2nd Lt. Cooke received a Military Cross and Cpl. Bayley and L/Cpl. Pickford were given DCMs.

Forshaw was invalided home on extended sick leave on 26 September. The following month he was given a hero’s welcome. Fêted by press and public as the ‘Cigarette VC’ on account of the cigarettes he had used to light bomb fuses throughout the Vineyard fighting, he received little peace. His home town of Barrow-in-Furness presented him with a sword of honour at a civic reception, and the proud burghers of Ashton-under-Lyne, home of the 9th Manchesters, made him a Freeman. On 18 October came the biggest ceremony of all, the investiture of his Victoria Cross at Buckingham Palace. Through it all, he bore himself with great dignity, even though he was far from fully recovered. Back home, he confided: ‘Shells have affected my eyes to some extent, and my nerves are somewhat out of order. I cannot concentrate my thoughts properly.’

![]()

William Thomas Forshaw was born on 20 April 1890, the eldest of two sons to Thomas Forshaw, of Fairfield Lane, Barrow-in-Furness. His father was head foreman at Vickers Shipyard.

Educated at Dalton Road Wesleyan School, Holker Street Boys School and Barrow’s Higher Grade School, he left home at eighteen to train as a teacher at Westminster College. After completing the course, he returned home to study for his intermediate exam. He helped pay his way by taking evening classes at his old senior school and Barrow Technical School, where his students included six Turks stationed in the town while a ship was being built for their government.

In the years leading to the outbreak of war, Forshaw taught at the Dallas Road School, Lancaster, and the North Manchester (prep) Grammar School. He was a fine athlete, played football and rugby, and later became an accomplished golfer and tennis player.

His connection with Ashton grew out of a friendship with a fellow teacher. A fine bass singer, he joined the Ashton Operatic Society, and also enlisted in the Ashton Territorial Battalion of the Manchester Regiment. Commissioned second lieutenant in May 1914, Forshaw was promoted lieutenant on the outbreak of war.

The beginning of hostilities interrupted his studies; he had been due to take his final exam in September. Instead, he found himself sailing for Egypt with the 42nd East Lancashire Division, where for the remainder of 1914 and the early part of 1915, the Lancashire Territorials continued their training. Forshaw evidently enjoyed himself during the battalion’s spell on the banks of the Suez Canal. At the Divisional sports day he won the 220 yd sprint, and he recorded:

The life there was a holiday for most of the officers and men, but I was acting as quartermaster and had a very busy time trying to get supplies over the canal by means of a hand-worked ferry boat, which averaged an hour and a half per trip. Still, the weather was perfect, and when one could steal an hour off there was some excellent bathing.

Following his services at Gallipoli, Forshaw’s promotion to captain was confirmed. A year later, Capt. Forshaw VC married a nurse in Ashton-under-Lyne.

Transferring to the 76th Punjabis, Indian Army in 1917, Forshaw took part in four frontier campaigns before retiring from the Army in November 1922. Teaching jobs, however, were hard to come by, even for a schoolmaster with a VC. Forshaw therefore decided to take a two-year appointment in the RAF Educational Service, in Egypt.

After leaving the RAF, he returned to England in 1925. He settled at Rushmere St Andrew, near Ipswich, and then Martlesham Hall. At each place he started a preparatory school for boys, but bankrupted himself in the process. Compelled to take a teaching job in an Ipswich council school, he drifted from job to job before deciding to pursue a new career.

Joining Gaumont British, Forshaw went on to specialise in the company’s Industrial Film Production Department. His interest in film and photography dated back to before the First World War. As a subaltern in Egypt and on the peninsula, he was noted as an enthusiastic photographer, several of his off-duty pictures appearing in the Ashton newspapers. After the war he branched out into writing and produced a number of commercial films.

During the Second World War he was a major in the 11th City of London (Dagenham) Battalion of the Home Guard, later serving as a staff officer. In 1941 he and his wife moved to Holyport, in Berkshire as evacuees. It was there, at his home, Foxearth Cottage, that he died on 26 May 1943. He had apparently suffered a heart attack while cutting a hedge in his garden.

Unusually, for an officer recipient of the Victoria Cross, Forshaw was buried in an unmarked grave at Touchen-End, near Maidenhead. There it was forgotten until October 1994, when efforts to trace his last resting place culminated in the dedication of a headstone provided by his old regiment. Two years later, Forshaw received further recognition when an English Heritage blue plaque honouring his memory was placed at Ladysmith Barracks, Ashton-under-Lyne.

Captain Robert Bonner, historian of the Manchester Regiment, who had done much to ensure Forshaw’s courage was remembered, remarked at the time: ‘It is very satisfying to have played a role in achieving for him his rightful recognition. It is something that should have been done many, many years ago. He was a colourful, popular young man at the time of the Great War. But, later, times were difficult for him.’