Chapter 1

INTRODUCTION TO THE STUDY OF FILM FORM AND REPRESENTATION

The purpose of this book is to analyze how American films have represented race, class, gender, sexuality, and ability throughout the twentieth century and into the early twenty-first. It is a basic principle of this work that by studying American film history, we can gain keen insights into the ways that different groups of American people have been treated (and continue to be treated). Images of people on film actively contribute to the ways in which people are understood and experienced in the “real world.” Furthermore, there are multiple and varied connections between film and “real life,” and we need to have agreed-upon ways of discussing those connections and their ramifications. Therefore, before examining in detail how specific groups of people have been represented within American cinema, we need to understand some preliminary concepts: how film works to represent people and things, how and why social groupings are and have been formed, and how individuals interact with the larger socio-cultural structures of the United States of America. This chapter introduces some basic ideas about film form, American history, and cultural studies.

Film Form

Film form refers to the constitutive elements that make a film uniquely a “film” and not a painting or a short story. All works of art might be said to have both form and content. Content is what a work is about, while form is how that content is expressed. Form and content are inextricably combined, and it is an old adage of art theory that “form follows content,” which means that the content of a work of art should dictate the form in which it should be expressed. For example, many different poems might have the same content – say, for example, a rose – but the content of a rose can be expressed in various forms in an infinite number of ways: in a sonnet, a ballad, an epic, a haiku, a limerick, and so forth. Each of these formal structures will create a different “take” on the content. For example, a limerick tends to be humorous or flippant, while a sonnet tends to be more serious and romantic. Likewise, different films with similar content can be serious, frivolous, artistic, intellectual, comedic, or frightening. Therefore, understanding how cinema communicates or creates meaning requires more than paying attention to what is specifically going on in the story (the film's content); it also requires paying attention to how various artistic choices (the film's form) affect the way the story is understood by the viewer.

Many entire books have been written analyzing the various formal elements of film but, for the purposes of this basic introduction, they can be broken into five main aspects: literary design, visual design, cinematography, editing, and sound design. The first aspect of film form, literary design, refers to the elements of a film that come from the script and story ideas. The literary design includes the story, the setting, the action, the characters, the characters' names, the dialog, the film's title, and any deeper subtexts or thematic meanings. Film is capable of many literary devices: metaphor, irony, satire, allegory, and so forth. Some films are black comedies and must be understood according to that form. Other films are dramas to be taken seriously while still others try to make us laugh by being deliberately juvenile. Yet other films try to shock or provoke us with new and unexpected ideas. Analyzing a movie's literary design is a good place to start when analyzing a film, but one should not ignore the four other axes of film form and how they contribute to a film's meaning.

Another broad aspect of film form has been labeled mise-en-scène, a French term for what goes into each individual shot (or uninterrupted run of film). Aspects of mise-en-scene include our second and third formal axes: the visual design of what's being filmed (the choice of sets, costumes, makeup, lighting, color, and actors' performance and arrangement before the camera) and the cinematographic design – that is, how the camera records the visual elements that have been dictated by the literary design. The cinematographic design includes things like the choice of framing, lenses, camera angle, camera movement, what is in focus and what is not. Each of these choices of mise-en-scene can affect the viewer's feelings toward the story and its characters. A room that is brightly lit may seem comfortable or even festive; that same room with heavy shadows may seem threatening or scary. If everyone in a crowd scene is wearing various shades of gray and black, the viewer will tend to see them as just a crowd; if one person is wearing red, the viewer will tend to focus on that one person. Similarly, a camera shooting up from the floor at a character will create a different feeling than a camera aimed at eye-level. In yet another example, if only one couple on a dance floor are kept in focus, the viewer will pay attention to them; if the whole ballroom is kept in focus, the viewer may choose to look in a number of directions.

The fourth axis of film form is called montage or editing, and refers to how all the individual shots the camera records are put together in order to create meaning or tell a story. Most movies are made up of hundreds and hundreds of shots which are edited together to make a full-length feature film. Many choices get made at the editing stage. Not only do filmmakers usually have multiple takes of the same scene to choose from, they also choose which shots to place together with other shots. It may seem obvious to an audience, since the editing would seem to need to follow the story (A follows B follows C), but an editor may choose to break up a shot of a group of people talking with individual close-ups of people in the group. Such a choice affects audience understanding by forcing the viewer to pay attention to just one person instead of the entire group. Audience identification with specific characters can be encouraged or discouraged in this manner. Montage also involves choosing the length of each shot. Usually, longer shot lengths are used to create quiet or contemplative moments, while action sequences or chases often are put together with short, quick shots.

The fifth and final formal axis of cinema is sound design. Although cinema audiences are usually referred to as viewers or spectators, audiences both watch and listen to films, and the same types of artistic choices that are made with the visual images are also made with the soundtrack. The dialog of some of the characters on the screen is easy to hear, while the dialog of others is inaudible (thus directing the audience member to pay attention to the conversation that the filmmakers want them to pay attention to). Most films have a musical score that the audience can hear but which the characters cannot. Choosing what type of music to play under a scene will greatly affect viewer comprehension – that is why the music is there in the first place – by directing the viewer toward the preferred understanding of the images. Playing a luscious ballad during a scene between a woman and her fiance helps create a romantic sense, but playing ominous music during the same scene may make the viewer think the man is out to hurt the woman (or vice versa).

Although this only begins to introduce the subject of film form, these few examples do point out how cinema's basic aesthetic qualities help to create meaning. Discussing how various types of people are represented in American cinema, then, requires more than analyzing only the stories and the characters. For example, let's imagine a film about both a white man and a Native American man. The story alternates between the two characters, showing their daily activities: getting up, eating, interacting with their family and friends, working, and then going to sleep. There would seem to be nothing necessarily biased or prejudiced according to this description of the film's content. Yet, in this hypothetical film, all the scenes with the white man are brightly lit, with the camera placed at eye-level; the shots are of medium length, and calm, pleasant music is used for underscoring. In contrast, all the scenes of the Native American man are composed with dark shadows, with the camera constantly tilted at weird angles; the shots are quick and choppy, and dark, brooding music is used for underscoring. Such choices obviously slant how a viewer is supposed to react to these two characters. The content of the film may have seemed neutral, but when the other axes of film form are analyzed, one realizes that the white man was presented in a favorable (or neutral) light, while the Native American man was made to seem shifty or dangerous.

The above example is an imaginary one, but throughout this book actual films will be analyzed in detail in terms of both content and form, in order to examine how various American identities are represented in American films. As the next chapters will discuss in detail, the Hollywood studio system developed certain traditions in its formal choices that would vastly affect how race, class, gender, sexuality, and ability were and are treated in mainstream narrative films. But before turning to specifics, we must also examine the social and political nature of American society itself, as well as the theoretical tools that have been developed to explore the relationship between film and “real life.”

American Ideologies: Discrimination and Resistance

The Constitution of the United States of America famously begins with these three words: “We the People.” Their importance highlights one of the founding principles of the nation: that the power of government is embodied not in the will of a dictator, nor in that of a religious leader or a monarch, but in the collective will of individual citizens. In conceptualizing “the power of the people,” the newly formed United States based its national identity on the principle of equality or, as Thomas Jefferson wrote in the Declaration of Independence, that “all men are created equal.” Yet, as admirable as these sentiments were (and are), the United States of the late 1700s saw some individuals as “more equal” than others. Jefferson's very words underline the fact that women were excluded from this equality – women were not allowed to vote or hold office, and they were severely hampered in opportunities to pursue careers outside the home. People of African descent were also regularly denied the vote, and the writers of the Constitution itself acknowledged (and thus implicitly endorsed) an institutional system of slavery against blacks and others. The Constitution did at least acknowledge the presence of African Americans in the country (although they were valued by the government as only three-fifths of a person). Native Americans were denied even this dubious honor and were considered aliens. Even being a male of European descent did not necessarily guarantee inclusion in the great experiment of American democracy, for many statesmen at the time argued that only landowners (that is, those of a certain economic standing) should have the right to vote or hold office.

Over the years, Americans have come to understand that the Constitution is a living document, one that can be and has been changed to encompass a wider meaning of equality. In America today, there is a general belief that each and every individual is unique, and should have equal access to the American Dream of “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.” Not everyone will necessarily reach the same levels of happiness and success, but most Americans believe that the results of that quest should be based on individual effort and merit rather than preferential treatment (or, conversely, exclusionary tactics). The United States professes that these opportunities are “inalienable rights.” However, just as in the late 1700s, barriers, conflicts, biases, and misunderstandings continue to hamper these ideals. While most American citizens philosophically understand and endorse these principles of equality, many of those same people also recognize that equality has not been totally achieved in the everyday life of the nation.

Why is there such a disparity between the avowed principles of equality and many citizens' actual lived experience? First, while ostensibly acknowledging that each person is unique, most of us also recognize that individuals are often grouped together by some shared trait. This grouping comes in many forms: by racial or ethnic heritage, by gender, by income level, by academic level, by sexual orientation, by geographic region, by age, by physical ability, and so forth. Almost invariably, such categorization of various identity types becomes a type of “shorthand” for describing people – a working-class Latino, a black deaf senior citizen, a Southern middle-class gay man. Quite often, this shorthand is accompanied by assumed traits that people belonging to a certain category supposedly have in common: that women are more emotional than rational, that gay men lisp, that African Americans are good dancers. When such oversimplified and overgeneralized assumptions become standardized – in speech, in movies, on TV – they become stereotypes. Stereotypes are often said to contain a “kernel of truth,” in that some women are more emotional than rational, some gay men do lisp, and some African Americans do excel at dance. The problems begin when people make unsupported leaps in logic and assume that everyone of a certain group is “naturally inclined” to exhibit these traits, thus reducing complex human diversity to simple-minded and judgmental assumptions.

In their oversimplification, stereotypes inevitably create erroneous perceptions about individuals. Stereotypes become even more problematic when they are used to favor certain groups over others, which unfortunately occurs quite commonly. While ostensibly living in a “free and equal” society, most Americans are aware that certain groups still have more opportunities and protection than others. In almost all of the categories listed above, there is one group that tends to have more access to “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness” than the others. Within race, those considered white or of Anglo-Saxon descent still seem to have more privilege and opportunity than do those of other races. Within gender, women are still working to achieve equity with men, while within sexual orientation, heterosexuality is more accepted and privileged than other orientations. And since notions of success and happiness are intricately tied to income level in contemporary US culture, one can see that working-class people hold less power than middle-class people (and that middle-class people in turn hold less power than do people of the upper classes). One need merely glance at the demographic makeup of Congress or the boardrooms of most major American corporations to see that wealthy heterosexual white men dominate these positions of power. American films over the past century also disproportionately focus on stories of strong and stalwart heterosexual white men finding happiness and success.

In everyday conversation, less privileged groups are frequently referred to as minority groups. Such a term positions these groups as marginal to the dominant group that holds greater power. The term also implies that the disempowered groups are smaller numerically than the dominant group – an implication that may not necessarily be true. Census statistics often indicate that there are slightly more women living in the United States than men, yet men hold far more social power and privilege than do women. Current population projections are forecasting that, in many states, white citizens will be outnumbered by other racial or ethnic groups some time in the near future. Hence, the term “minority group” more often refers to types of people with less social power than to any group's actual size.

One common method of keeping minority communities on the margins of power has been to pit their struggles for equality against one another, while the dominant group continues to lead. Another method has been to exclude members of minority groups from being considered “American” in the first place. The creation of a sense of national identity consistently involves social negotiations of who gets included and who gets excluded. Identity in general becomes more fixed when it is able to define what it is not : someone who is white is not black; a man is not a woman; a heterosexual is not a homosexual. America gains a greater sense of itself through such juxtapositions: it is not a British colony, it is not the various nations of Native Americans, and it is not the other countries that make up the American continents (which can also lay claim to the name “America”). Consequently, if certain population groups can be considered “alienable,” then it becomes easier to feel that they are not entitled to those “inalienable rights” that “We the People of the United States of America” have supposedly been granted.

While women, homosexuals, the differently abled, and people of non-white heritage have made tremendous gains in social power during the last few decades, white heterosexual men still dominate the corridors of power in America. Many people feel that this is “how things ought to be,” that this is simply the “natural order of things.” In theoretical terms, considering white heterosexual males obviously or essentially better (stronger, more intelligent, etc.) is called an ideological assumption. Ideology is a term that refers to a system of beliefs that groups of people share and believe are inherently true and acceptable. Most ideological beliefs are rarely questioned by those who hold them; the beliefs are naturalized because of their constant and unquestioned usage. They are, to use a word made famous in the Declaration of Independence, “self-evident.” No one needs to explain these ideas, because supposedly everyone knows them.

When an ideology is functioning optimally within a society or civilization, individuals are often incapable of recognizing that these ideas are socially constructed opinions and not objective truths. We call these assumptions dominant ideologies, because they tend to structure in pervasive ways how a culture thinks about itself and others, who and what it upholds as worthy, meaningful, true, and valuable. The United States was founded on and still adheres to the dominant ideology of white patriarchal capitalism. This does not mean that wealthy white men gather together in some sort of conspiracy to oppress everyone else in the nation, although such groups have been formed throughout American history in order consolidate and control power. Rather, white patriarchal capitalism is an ideology that permeates the ways most Americans think about themselves and the world around them. It also permeates most American films.

White patriarchal capitalism entails several distinct aspects. The first – white – refers to the ideology that people of Western and Northern European descent are somehow better than are people whose ancestry is traced to other parts of the world. Patriarchal (its root words mean “rule by the father”) refers to a culture predicated on the belief that men are the most important members of society, and thus entitled to greater opportunity and access to power. As part of American patriarchy, sexuality is only condoned within heterosexual marriage, a situation that considers all other sexualities taboo and reinforces women's role as the child-bearing and child- raising property of men. The third term – capitalism – is also a complex one, which multiple volumes over many years have attempted to dissect and define, both as an economic system and as a set of interlocking ideologies.

For the working purposes of this introduction, capitalism as an ideology can be defined as the belief that success and worth are measured by one's material wealth. This fundamental aspect of capitalism has been so ingrained in the social imagination that visions of the American Dream almost always invoke financial success: a big house, big car, yacht, closets full of clothes, etc. Capitalism (both as an economic system and as an ideology) works to naturalize the concept of an open market economy, that the competition of various businesses and industries in the marketplace should be unhindered by governmental intrusion. (The US film industry, a strong example of capitalist enterprise, has spent much of its history trying to prevent governmental oversight.) One of the ideological strategies for promoting capitalism within the United States has been in labeling this system a “free” market, thus equating unchecked capitalism with the philosophies of democracy. Capitalism often stands in opposition to the ideology and practice of communism , an economic system wherein the government controls all wealth and industry in order to redistribute that income to the population in an equitable fashion. (The history of the twentieth century showed that human greed usually turns the best communist intentions into crude dictatorships.) Socialism , an economic and ideological system mediating capitalism and communism, seeks to structure a society's economic system around governmental regulation of industries and the equitable sharing of wealth for certain basic necessities, while still maintaining democratic values and a free market for most consumer goods. Since the United States was founded under capitalism, American culture has largely demonized socialism and communism as evil and unnatural, even though many US government programs can be considered socialist in both intent and practice.

The ideology of white patriarchal capitalism works not only to naturalize the idea that wealthy white men deserve greater social privilege, but to protect those privileges by naturalizing various beliefs that degrade other groups – thus making it seem obvious that those groups should not be afforded the same privileges. Some argue that capitalism can help minority groups gain power. If a group is able to move up the economic ladder through capitalist means, then that group can claim for itself as much power, access, and opportunity as do the most privileged Americans. As persuasive as this argument is (as can be seen by its widespread use), capitalism has often worked against various minority groups throughout US history. The wealthy have used their position to consolidate and insure their power, often at the expense of the rest of the population. Since this wealthy group has almost exclusively been comprised of white men, the dissemination of racist and sexist stereotypes has helped keep people of color and women from moving ahead economically. To use an early example, arguing that individuals of African descent were barely human allowed slavery to continue to thrive as an economic arrangement that benefited whites.

Today, racist, sexist, and homophobic attitudes work to create in corporate culture a glass ceiling, a metaphoric term that describes how everyone but white heterosexual males tends to be excluded from the highest executive levels of American industries.

In this way, one can see how the impact of social difference (race, gender, sexuality, physical ability) can have an impact upon one's economic class status. In fact, the social differences that this book attempts to discuss – race, gender, class, sexuality, and ability – cannot be readily separated out as discrete categories. For example, people of color are men and women, rich and poor, straight and gay. Being a black female means dealing with both patriarchal assumptions about male superiority and lingering ideas of white supremacy. Being a lesbian of color might mean one is triply oppressed – potentially discriminated against on three separate levels of social difference. Encountering real-world prejudice on account of those differences, non-white, non-male, and non-heterosexual people, as well as those considered disabled, may have trouble finding good jobs and subsequent economic success.

Most ideologies, being belief systems, are only relatively coherent, and may sometimes contain overlaps, contradictions, and/or gaps. The dominant ideology of any given culture is never stable and rigid. Instead, dominant ideologies and ruling assumptions are constantly in flux, a state of things referred to by cultural theorists as hegemony – the ongoing struggle to maintain the consent of the people to a system that governs them (and which may or may not oppress them in some ways). Hegemony is thus a complex theory that attempts to account for the confusing and often contradictory ways in which modern Western societies change and evolve. Whereas “ideology” is often used in ahistorical ways – as an unchanging or stable set of beliefs – hegemony refers to the way that social control must be won over and over again within different eras and within different cultures. For example, we should not speak of patriarchal ideology as a monolithic concept that means the same thing in different eras and in different situations. Rather, the hegemonic struggle of patriarchy to maintain power is a fluid and dynamic thing that allows for its ongoing maintenance but also the possibility of its alteration. For example, specific early twentieth-century patriarchal ideologies were challenged and changed when women won the right to vote in 1920, but that did not destroy the hegemony of American patriarchy.

Thus, the dominant ideology of a culture is always open to change and revision via the ebb and flow of hegemonic negotiation, the processes whereby various social groups exert pressure on the dominant hegemony. In another example, over the last fifty years, American civil rights groups have worked to expose and overturn the entrenched system of prejudice that has oppressed their communities for generations. Often, these fights include attempts to instill pride and self-worth in the minority groups that have been traditionally disparaged. In the process, the ideological biases of racial superiority are being challenged, but the basic assumption that individuals can be grouped according to their race is not. While these efforts attempt to disrupt one level of assumptions, a more basic ideological belief is kept intact. In this case the dominant hegemonic concept of racial difference as a valuable social marker remains untouched, even as the individual ideologies of white supremacy are challenged. (More recent cultural theorists have begun to challenge the very notion of such categorizations, a topic explored more fully in future chapters.)

Ideological struggle is therefore an ongoing political process that surrounds us constantly, bombarding individuals at every moment with messages about how the world should and could function. Such struggles can be both obvious and subtle. One obvious way of disseminating and maintaining social control is through oppressive and violent means, through institutions such as armies, wars, police forces, terrorism, and torture – institutions known as repressive state apparatuses (RSAs) . Violent, repressive discrimination is part of American history, as evidenced by terrorist groups such as the Ku Klux Klan, political assassinations, police brutality, and the continued presence of hate crimes. More subtly, the state can also enforce ideological assumptions through legal discrimination. For example, the so-called Jim Crow Laws of the American South during the first half of the twentieth century legally inscribed African Americans as second-class citizens. Current examples would be the lack of federal laws that prohibit discrimination based on gender or perceived sexual orientation. Such legal discrimination tacitly helps maintain occupational discrimination. What these few examples also show is that discrimination and bias are systemic problems as well as individualized ones. Just as a single person can be a bigot, those same biases can be incorporated into the very structures of our “free” nation: this is known as institutionalized discrimination .

While institutionalized discrimination and other oppressive measures overtly attempt to impose certain ideologies upon a society, there are still more subtle means of doing so that often do not even feel or look like social control. Winning over the “hearts and minds” of a society with what are called ideological state apparatuses (ISAs) usually proves more effective than more oppressive measures, since the population acquiesces to those in power frequently without even being aware that it is doing so. ISAs include various non-violent social formations such as schools, the family, the church, and the media institutions – including film and television – that shape and represent our culture in certain ways. They spread ideology not through intimidation and oppression, but by example and education. In schools, students learn skills such as reading and math, but they are also taught to believe certain things about America, and how to be productive, law-abiding citizens. The enormously popular Dick and Jane books taught many American youngsters not only how to read, but also how boys and girls were supposed to behave (and most importantly, that boys and girls behave differently). Institutionalized religion is also an ideological state apparatus, in which theological beliefs help sustain ideological imperatives. Many Christian denominations during the country's first century used the Bible to justify slavery and segregation of the races. Some faiths still demonize homosexuality and argue that women should subjugate themselves to men. Others regard children born with differing physical abilties as signs of sin or evil. Even the structure of the family itself is an ISA, in which sons and daughters are taught ideological concepts by their parents. In the United States, families have traditionally been idealized as patriarchal, with the father as the leader. Parental prejudices (about the lower classes, about homosexuals, about the disabled, about other races or ethnicities) can also be passed down to their offspring, helping maintain those beliefs.

As these examples of ISAs show, ideology functions most smoothly when it is so embedded in everyday life that more overt oppressive measures become unnecessary. In fact, the use of oppression usually indicates that large sections of a society are beginning to diverge from the dominant ideology. At their most successful, ISAs act as reinforcements for individuals who have already been inculcated into dominant ideology. Such individuals are said to have internalized ideology , or to have adopted socially constructed ideological assumptions into their own senses of self. Such internalizing can have significant effects on people, especially members of minority groups. No matter what social group one might identify with, we all are constantly bombarded by images, ideas, and ideologies of straight white male superiority and centrality, and these constructs are consciously and unconsciously internalized by everyone. For straight white men, those images can reinforce feelings of superiority. For everyone else, those images and ideas can produce mild to severe self-hatred or create a psychological state in which individuals limit their own potential. In effect, we might allow the dominant ideology to tell us what we are or are not capable of – that women are not good at math, that African Americans can only excel at sports, that people from the lower classes must remain uneducated, that someone in a wheelchair cannot be an elected official, or that being homosexual is a shameful thing. Possibly the least noticeable but potentially most damaging, this type of internalized discrimination is sometimes termed ego-destructive , because it actively works against an individual's sense of psychological well-being. Such ego-destructive ideologies may be especially harmful because they are often fostered by those groups and individuals who allegedly love and nurture us: rejection from families and religions is still a common occurrence for people who are perceived as different from the “norm.”

The strength and tenacity of such internalized ideologies within an efficiently working hegemonic system allow people to consider their society open and free, since it appears that no one is forcing anyone else to live a certain way, or keeping them from reaching their highest possible levels of achievement. Yet the subtlety of ideological state apparatuses and the subconscious impact of ego-destructive discrimination severely undercut and problematize the avowed principles of liberty and equality upon which the United States was founded. Hallowed as these principles are, the functioning of white patriarchal capitalism as our nation's dominant ideology militates against social equality in a variety of ways.

Culture and Cultural Studies

While the school, the church, and the family serve as classic examples of ideological state apparatuses, potentially the most pervasive of ISAs (at least in the past century) is the mass media – newspapers, magazines, television, radio, film, and now the Internet and the World Wide Web. Many theorists feel that in today's electronic world, the media has more influence on cultural ideas and ideologies than do schools, religions, and families combined. The bulk of this book will examine historically how one branch of this mass media, the American cinema, has worked to exemplify and reinforce (and more rarely challenge) the hegemonic domination of white patriarchal capitalism.

One of the first arguments used to resist focusing on American cinema as a conveyer of ideological messages is that Hollywood movies are merely “entertainment.” Consequently, as the argument goes, academics are reading too much into these things. What do ideas like ideology and hegemony have to do with mindless escapism? To answer such questions, one has to recognize that cinema (and all other mass media) are important parts of American culture. Culture refers to the characteristic features of a civilization or state, or the behavior typical of a group or class. Culture is thus deeply connected to ideology: one might say it is the “real- world” manifestation of ideology, since characteristic features, social behaviors, and cultural products all convey ideology.

Historically, European culture judged itself to be superior to all other cultures on the globe. “True” culture was thought to be synonymous with Western notions of high art – classical music, “serious” literature and theater, etc. – and other cultures were judged to be deficient by those standards. Today we try to discuss different cultures without making such value judgments; we also understand that any given group's culture is more than just its most “respectable” and officially “important” art works. Culture also encompasses the modes of everyday life: how one behaves in a social situation, the type of clothes one wears, the slang one uses when talking to friends, etc. This definition of culture includes the so-called low art of popular music, comic books, paperback novels, movies, and television – forms of culture that interact with far more people than do those found only in museums or opera houses. Even language itself shapes and is shaped by culture, and thus conveys ideological meanings. For example, the Euro-American cultural tradition that associates “white” with goodness and “black” with evil cannot help but influence how we think about race, which we often define in the same terms.

Within any given society, there are multiple cultures that differ in varying degrees from one another. In the United States, one can find a variety of cultures: hip-hop, Chicano, Mennonite, conservative Christian, and yuppie, just to name a few. These cultures co-exist and may overlap (for example, a Chicano yuppie), but cultural groupings rarely exist in equal balance with one another. Rather, the culture of the ruling or most powerful group in a society tends to be the dominant culture, expressing its values and beliefs through ideologies and other cultural forms. The group with the most control has the greater means to produce and disseminate their preferred cultural attitudes throughout the rest of the society – their music, their literature, their standards of behavior become the norm for the rest of the society. For example, Native Americans have historically had less opportunity than Anglo Americans to get the funding or training necessary to make films or television programs. Consequently, the white man's version of “how the West was won” has been filmed and televised literally thousands of times, while Native Americans have had very little chance to present their viewpoint of that era on film or video.

The culture of any marginalized or minority group is often labeled a subculture. Subcultures can have their effect on the dominant culture by contributing to the active hegemonic negotiation of dominant ideology, but usually this only happens to the extent that a subculture's concerns can be adapted to the needs of the dominant ruling interests. For example, hip-hop and rap music styles have crossed over into mainstream popular music – but in an altered (and some might say watered-down) version. This is broadly called commodification (turning something into a product for sale) and more specifically incorporation (the stripping of an ideology or cultural artifact's more “dangerous” or critical meanings so that the watered-down artifact can be sold to mainstream culture). Another good example of this process is the recent history of earrings worn on men. Some men in the 1970s started to wear earrings as a “coming out” gesture – to announce to the world that they belonged to the emerging gay male subculture. As an act of coming out, the gesture was political and meant to challenge a dominant culture that ignored or suppressed the existence of gay men. In the 2000s, however, many, many men wear earrings – not because they want the world to know that they are gay, but because earrings for men have become a commodity that can be bought and sold as part of a depoliticized fashion trend. The gay political meaning of men wearing earrings has been stripped from the act – it was commodified and incorporated within the dominant culture.

In recent decades, scholars in various disciplines (sociology, political science, literature, communications, history, media studies) have begun to study and theorize concepts and issues surrounding culture and ideology. This interdisciplinary research has coalesced under the term cultural studies. As its theorists come from such different backgrounds, cultural studies as a field of academic inquiry has consistently focused on multiple aspects of how culture works (and needs to be analyzed), but one of the basic foundations for this new discipline has been that every cultural artifact – book, movie, music video, song, billboard, joke, slang term, earring, etc. – is an expression of the culture that produces it. Every cultural artifact is thus a text that conveys information, carrying the ideological messages of both its authors and the culture that produced it. As a result, many cultural studies scholars are interested in how media texts express a view of the world, how these expressions create ideological effects, and how the users of such texts make meaning from them. This area, sometimes called image studies , looks at the processes of representation – the systems we use to communicate and understand our world – language, art, speech, and more recently TV, movies, and newer forms of media. These are representational systems that show us reconstructed (or mediated ) versions of life, not “real life” itself. Most US citizens have never been to China, but probably know something about it from reading books or newspapers, or seeing images of it on television or at the movies. Since all media texts reflect in some way the ideological biases of the culture from which they emanate, the images of China shown in Hollywood movies or on American television will be different from the mediated images of China made in some other area of the world (and different from China's own images of itself).

There are two stages of making meaning within any given text: encoding and decoding. Encoding encompasses the actual production of the text. A common method of analyzing encoding in film studies has been termed auteur studies . French for “author,” the auteur concept understands film or films as the imaginative work of a single specific artist, usually the director. By examining a number of films made by the same auteur, one can supposedly find common stylistic choices (ways of using the camera, editing, etc.) as well as common themes. Auteur studies became popular during the 1960s, and even now journalists will refer to “the latest Quentin Tarantino film” or “a typical Steven Spielberg picture.” The auteur theory argues that it is important to know who made a film, because aspects of a filmmaker's personality and social position will affect the meanings encoded within it. Historically, straight white men in Hollywood made most American films; it has only been in recent decades that women, people of color, and/or homosexuals have had greater opportunities to make films.

Thus, during the encoding stage, the maker(s) of a film place meaning, including ideological meaning, into the text. Sometimes this involves specific, overt editorializing: a character gives a speech about a certain issue, or the entire story attempts to teach a moral lesson. However, the encoding of ideological meaning need not be so obvious; it might be done casually, and even unconsciously. Certain choices in creating mood or emotion, or in fostering audience sympathy (or antipathy), will also carry ideological weight. (Recall our earlier discussion of the hypothetical film about a white man and a Native American man.) To many, the process of encoding may initially sound like it applies solely to the production of propaganda , in which ideas, opinions, or allegations are presented as incontestable facts in order to sway public opinion toward or away from some cause or point. Texts that are labeled propaganda are usually encoded with overt ideological messages – cultural artifacts like advertisements, public service announcements, and political speeches. Hollywood movies are rarely labeled propaganda, yet they always encode certain ideologies. In other words, while all propaganda conveys ideological messages, not all texts are or should be labeled propaganda.

Students sometimes want to ask about a film text, “Did the author really mean it that way?” Such a question assumes that filmic analysis is “reading too much into things” unless one can find definite evidence of a filmmaker's intent. The response to this criticism is that all texts encode ideological meanings and messages, but those messages are not always consciously embedded in the text by its producer(s). Usually, filmmakers simply want to make a good film, tell an entertaining story, and sell tickets. Yet what is considered good or entertaining is itself going to differ according to cultural and ideological standards. Furthermore, the makers of cultural texts are not somehow removed from or above the society in which they live. They are just as much shaped by the dominant ideology as anyone else – and this can have an unconscious effect on what they put into their work. A white heterosexual middle-class Protestant male is going to have had a certain experience of life that will translate in some fashion into the films he writes or directs, even if he is not aware of it. Similarly, a non-white or female or homosexual or disabled filmmaker is going to have had a different life experience that will result in him or her making a different type of film (consciously or unconsciously). Also, a film from the 1950s is recognizably different from a film from the 1970s, not only because of the changes in cars and fashions, but also because of the changes in the ideological assumptions about social issues (such as race, class, gender, sexuality, and ability).

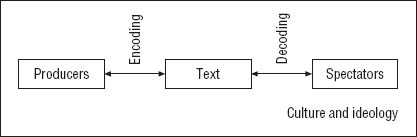

A cultural studies model of encoding and decoding. Producers, texts, and spectators all exist within larger spheres of culture and ideology.

The other stage of making meaning, decoding, involves the reception of a text. Once a text is produced, it is distributed to others (to be read, listened to, watched, worn, etc.). Those who use the produced text (that is, the audience) then decode the text's meanings on the basis of their own conscious and unconscious cultural, ideological positioning(s). In other words, producers, texts, and receivers make up a system of communication or meaning production, and that system exists within the larger social spheres of culture and ideology. Like encoding, decoding can be overt or subliminal. At certain times, an audience member will consciously recognize she or he is being “preached to.” If an ideological position becomes too strong or apparent, people may easily reject it as propaganda (especially if the ideology being espoused challenges their own). Yet, at other times, the messages may be decoded below one's consciousness. An imbalance that favors men instead of women as the main characters of Hollywood films might be decoded by audiences (without ever stopping to really think about it) as meaning that men are more important (or do more important things) than women.

When producers and readers share aspects of the same culture, texts are more easily decoded or understood. (If you doubt that, try reading a newspaper written in a language you do not understand!) However, not every reader is going to take (or make) identical meanings from the same text. Depending upon their own cultural positioning, different people may decode texts in different ways – sometimes minutely different, sometimes greatly so. Readings that decode a text in accordance with how it was encoded are said to be dominant readings . On the other side of the spectrum are oppositional readings , which actively question the ideological assumptions encoded in a text. Most readings lie somewhere in between these two extremes. Negotiated readings resist some aspects of what has been encoded, but accept others. Frequently, members of minority groups have social standpoints that differ from those encoded in mainstream texts, and sometimes this allows such individuals to perform readings that are more regularly negotiated or oppositional.

In most cases, Hollywood filmmakers don't want moviegoers to question the politics of their films. Hollywood promotes its films not as political tracts but as mindless escapism, and an audience member who accepts that tenet will rarely be alert to the cultural and ideological assumptions that the films encode and promote. (One should remember that ideology is often most effective when it goes unnoticed.) The fact that Hollywood films are generally understood as mere entertainment (without political significance) is itself an ideological assumption, one that denies the importance of image studies and therefore represents white patriarchal capitalist film practice as neutral, natural, and inevitable.

Yet the act of performing a negotiated or oppositional reading is not in and of itself a radical denunciation of dominant cinema. (After all, even the oppositional spectator has signaled his or her “approval” of the text by purchasing a ticket to the film.) While such readings may criticize and critique certain ideological notions, they are nonetheless created within the same basic hegemonic framework as are dominant readings. They cannot completely negate the ideological messages found in the text, only resist them. Still, oppositional and negotiated readings can have an effect on the hegemonic negotiation of dominant ideologies throughout time. When a certain oppositional reading strategy grows within a culture to the point that future similar texts are no longer accepted by consumers, then certain ideological assumptions must be altered, and future texts may exhibit those changes. As we shall see throughout this book, the overtly racist and sexist images that were found in many films from previous decades are – in many cases – no longer considered acceptable in the twenty-first century. Nonetheless, white patriarchal capitalism maintains its hegemonic dominance, in both American film and culture-at-large.

Case Study: The Lion King (1994)

Issues of culture and ideology can be illustrated by examining a text that many people would probably consider totally apolitical and meaningless except as mere entertainment – the Walt Disney Company's animated feature The Lion King (1994). One of the biggest box office successes in motion picture history, The Lion King embodies what most people refer to as escapist family entertainment. Since the film was about animals – and cartoon animals at that – the film might seem to have little to say about human relations or ideologies. Yet, since cultural artifacts always reflect in some way the conditions of their production and reception, it is not surprising that The Lion King has interesting things to convey about late twentieth-century American culture and its dominant ideology – white patriarchal capitalism. These messages reflect the place and time in which the film was made: the songs are typical 1990s soft rock music, some of the jokes refer to current events, and the storyline evokes concepts popularized in the 1990s by New Age spirituality. Using ideas and concepts that were familiar and reassuring to many Americans probably helped strengthen the film's popularity.

According to our cultural studies model, the cultural artifact The Lion King is the text under consideration, its producer is the Walt Disney Company (the animators, performers, and other employees involved in making the film), and the readers are all the people who have seen the film since its release in 1994. The Disney filmmakers encoded meaning into the cartoon, and every viewer, whether preschooler or senior citizen, works to understand the text by decoding it. The film was arguably as popular as it was because it playfully and joyfully encoded dominant hegemonic ideas about white patriarchal capitalism into its form and content: the film's story is a coming-of-age tale in which Simba, a young male lion, learns that his proper place in the world is to be the leader of those around him. Readers who enjoyed the film were probably performing dominant readings of the text, as they cheered on the young lion's rise to the throne, defeating his adversaries amid song and dance and colorful spectacle.

Yet, while the film was a huge box office hit, there emerged a small but vocal opposition to The Lion King, criticizing it on a number of levels. These critics of the film performed oppositional and/or negotiated readings. For example, some readers were annoyed that the film focused on patriarchal privilege by dramatizing how a son inherits the right to rule over the land from his father. The film literally “nature”-alizes this ideology by making it seem as if this is how real-life animals behave, when in fact female lions play active roles in the social structure of actual prides, a detail the film minimizes (and which, by extension, minimizes the importance of females in human society). The female lions in the film are minor “love interest” characters, and females of other species are almost non-existent. One might also note that the film's very title is suggestive of male authority and supremacy – lions and kings are longstanding symbols of patriarchy.

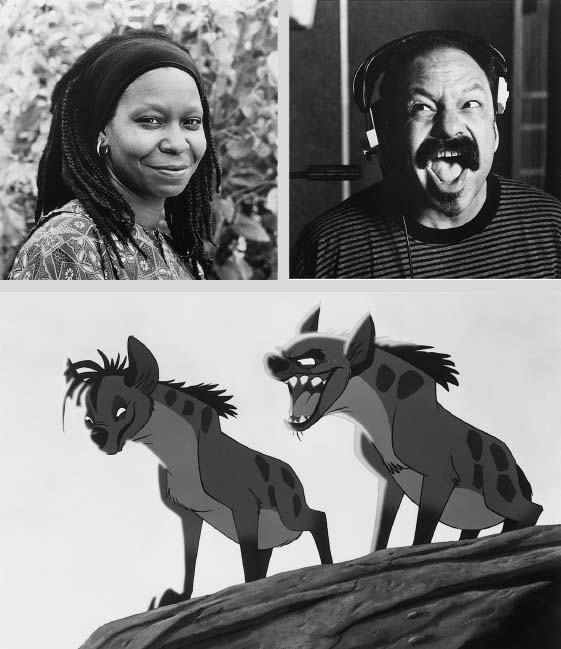

Scar's moronic and evil sidekicks are voiced by actors of color, Whoopi Goldberg and Cheech Marin. The Lion King, copyright © 1993, The Walt Disney Co. Top left, photo: Umberto Adaggi; top right, photo: Michael Ansell

Uncle Scar preens with an arched eyebrow (a stereotypical signifier of male homosexuality) as he plots against Simba, the “true” and “rightful” ruler of the jungle, in Walt Disney’s The Lion King (1994). The Lion King, copyright © 1993, The Walt Disney Co.

Other oppositional or negotiated readings noted that the first Disney animated feature to be set in Africa had erased all evidence of human African culture, and employed white musicians to write supposedly “African” music. (This is a good example of the dominant culture industry commodifying and incorporating African style while ignoring the politics of race and nation.) Furthermore, Simba and his love interest are both voiced by white actors. Disney did hire a few African American actors as character voices (including the assassinated patriarch), but some viewers felt that these characters came close to replicating derogatory racial stereotypes. For example, although the baboon character Rafiki (voiced by African American actor Robert Guillaume) holds a place of respect in the film as the community's mystic/religious leader, he frequently acts foolish and half-crazed, a variation on old stereotypes used to depict African Americans. Furthermore, two of the villain's dim-witted henchmen were also voiced by people of color (Whoopi Goldberg and Richard “Cheech” Marin), linking their minority status to both stupidity and anti-social actions.

Villainy in the film is also linked to stereotypical traits of male homosexuality. The villainous lion Scar is voiced by Jeremy Irons with a British lisp and an arch cynicism; the Disney animators drew him as weak, limp-wristed, and with a feminine swish in his walk. Other characters refer to him as “weird,” and, in his attempt to usurp the throne for himself, he disdains the concept of the heterosexual family. Scar's murder of Simba's father and his attempt to depose the “rightful” heir to the throne posit him as a threat to the “natural order” itself (a fact made literal when Scar's rule results in the environmental desolation of the savanna). It is only with the restoration of Simba to the throne that the land comes back to life, in a dissolve that makes the change seem miraculously immediate. Perhaps most disturbingly, the film connects Scar's implied homosexuality with one of the twentieth century's most heinous evils: his musical solo, complete with goose-stepping minions, is suggestive of a Nazi rally.

Immediately, the question of which reading is “correct” gets raised. Are all these people who were bothered by The Lion King, those who performed oppositional readings, getting antagonistic over nothing? Or do they know what is really going on in the film, while everybody else (performing dominant readings) is just not “getting it”? A cultural studies theorist would answer that there are no right or wrong readings, but rather different interpretive strategies. There is no single definitive reading of any text. If a reader decodes a certain understanding of The Lion King, and can point to specific examples from the film to support his or her reading, then that reading is valid. And in order to make a persuasive defense of one's reading of a film (instead of just saying “I liked it – I don't know why”), one needs to work at finding supporting textual evidence – the specific ways the text uses film form to encode meaning. (Note how the oppositional reading just presented pointed out story elements, the actors involved, how the characters were drawn, the use of music, and even aspects of editing.) This process of analysis need not destroy one's pleasure in the text. Learning to analyze film form and ideology can enrich and deepen one's experience of any given text, and one can become a more literate, and aware, media consumer.

This book hopes to provide its readers with the tools and encouragement to become active decoders – to help students develop the skills needed to examine media texts for their social, cultural, and ideological assumptions. Throughout this book, specific films will be decoded from divergent spectator positions, pointing out how the context of social and cultural history can and does influence different reading protocols. Furthermore, one will see that judging textual images as merely “positive” or “negative” vastly oversimplifies the many complex ways that cultural texts can be and are understood in relation to the “real world.” This textbook itself is part of American culture, and thus meshes in its own way with the dominant and resistant ideologies within which it was forged. Its ultimate aim is not to raise its readers somehow out of ideology (an impossible task), but to make its readers aware of the ideological assumptions that constantly circulate through American culture, and especially through its films.

Questions for Discussion

1 What labels do you apply to your own identity? What labels do other people apply to you? Ultimately, who has the right to name or label you?

2 Can you think of other cultural artifacts (like rap music or earrings on men) that have been developed in a specific subculture and then incorporated into dominant culture? How was the artifact changed when it went mainstream?

3 What is your own ideological positioning? What are some of the ideologies you may have internalized? Do any of them clash with your own self-identity?

Further Reading

Althusser, Louis. Lenin and Philosophy and Other Essays. New York: Monthly Review Press, 1971.

Bordwell, David and Kristin Thompson. Film Art: An Introduction. New York: McGraw Hill, 2001.

Gray, Ann and Jim McGuigan. Studying Culture: An Introductory Reader. New York: Oxford University Press, 1997.

Hall, Stuart, Dorothy Hobson, Andrew Lowe, and Paul Willis, eds. Culture, Media, Language. London: Unwin Hyman, 1980.

Hebdige, Dick. Subculture: The Meaning of Style. London: Methuen, 1979.

Morley, David and Kuan-Hsing Chen, eds. Stuart Hall: Critical Dialogues in Cultural Studies. New York: Routledge, 1996.

Turner, Graeme. British Cultural Studies: An Introduction. New York: Routledge, 1996.

Williams, Raymond. Marxism and Literature. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1977.

Williams, Raymond. Problems in Materialism and Culture. London: NLB, 1980.