Chapter 3

THE CONCEPT OF WHITENESS AND AMERICAN FILM

It may seem odd to begin an exploration of the representations of racial and ethnic minorities with a chapter on the images of white people in American cinema. However, to fully understand how certain people and communities are considered to be racial minorities, it is also necessary to examine how the empowered majority group conceives of and represents itself. Doing so places white communities under a microscope, and reveals that the concept of whiteness (the characteristics that identify an individual or a group as belong to the Caucasian race) is not as stable as is commonly supposed. Under white patriarchal capitalism, ideas about race and ethnicity are constructed and circulated in ways that tend to keep white privilege and power in place. Yet surveying representations of whiteness in American film raises fundamental questions about the very nature of race and/or ethnicity. Although it may surprise generations of the twenty-first century, some people who are now commonly considered to be white were notconsidered so in the past. The most common designation of whiteness in the United States is the term WASP, which stands for White Anglo-Saxon Protestant. People of non-Anglo-Saxon European ancestry have historically had to negotiate their relation to whiteness. If American culture had different ideas about who was considered white at different times over the past centuries, then claims about race and ethnicity as absolute markers of identity become highly problematic.

This chapter explores the differing socio-historical and cinematic constructions of whiteness throughout the history of American film. It examines the representations of several (but not all) of the communities that were not originally welcomed into American society as white, but which have been more recently assumed to belong to this racial category. The following discussion examines how these groups were represented with certain stereotypes, how these communities developed strategies for acceptance by white society, and how cinema functioned as part of this cultural negotiation. We also discuss a population group, Arab Americans, that many currently consider unable to blend into white society, even though a number of Arab American individuals have done so. But first, the chapter begins with a discussion of how film works within dominant hegemonic culture to subtly – and almost invisibly – speak about the centrality of whiteness.

Seeing White

One of the hardest aspects of discussing how white people are represented in American cinema (and in Western culture-at-large) is the effort it takes for individuals even to see that racial/ethnic issues are involved with white characters or stories. By and large, the average moviegoer thinks about issues of race only when seeing a movie about a racial or ethnic minority group. For example, most romantic comedies find humor in how male and female characters each try to hold the upper hand in a relationship. Yet Two Can Play That Game(2001), starring two African American actors (Morris Chestnut and Vivica A. Fox), is often regarded as a “black” film, whereas You’ve Got Mail(1998), starring two white actors (Tom Hanks and Meg Ryan), is usually regarded as simply a romantic comedy, and not as a “white” film. Similarly, audiences, critics, and filmmakers considered Spawn(1997) to be a film about an African American superhero, whereas Batman(1991) was simply a film about a superhero – period. These points underscore the Hollywood assumption that all viewers, whatever their racial identification, should be able to identify with white characters, but that the reverse is seldom true. Even today many white viewers choose not to see films starring non-white actors or films set in minority ethnic environments, allegedly because they feel they cannot identify with the characters. Because of that fact, Hollywood tends to spend more money on white stars in white movies, and far less money on non-white actors in overtly racial or ethnic properties.

The very structure of classical Hollywood narrative form encourages all spectators, regardless of their actual color, to identify with white protagonists. This may result in highly conflicted viewing positions, as when Native American spectators are encouraged by Hollywood Westerns to root for white cowboys battling evil Indians. This situation was especially prevalent in previous decades, when nonwhite actors were rarely permitted to play leading roles in Hollywood films, and when racialized stereotypes in movies were more obvious and prevalent. However, in an acknowledgement of our population’s diversity, over the last several decades an ever-increasing number of non-white characters have been appearing in Hollywood movies. More and more films each year now feature non-white leads, and even more regularly, non-white actors in supporting roles. Sometimes this practice is referred to as tokenism – the placing of a non-white character into a film in order to deflate any potential charge of racism. Token characters can often be found in small supporting roles that are peripheral to the white leads and their stories. For example, in war movies featuring mixed-race battalions, minor black and Hispanic characters frequently get killed off as the film progresses, leaving a white hero to save the day. This phenomenon has become so prevalent that some audience members consider it a racist cliché. For many others, however, the phenomenon goes unnoticed, and the dominance of whiteness remains unquestioned.

Film scholar Richard Dyer’s work on how cinema represents whiteness ties this unthinking (or unremarked-upon) white centrism to larger ideological issues of race. As pointed out in chapter 1, a society’s dominant ideology functions optimally when individuals are so imbued with its concepts that they do not realize that a social construct has been formed or is being reinforced. The relative cultural invisibility of whiteness within the United States serves as a perfect example of this idea: the white power base maintains its dominant position precisely by being consistently overlooked, or at least unexamined in most mainstream texts. Unless whiteness is somehow pointed out or overemphasized, its dominance is taken for granted. A rare Hollywood film such as Pleasantville(1998) calls attention to whiteness, even down to its black-and-white visual design, in which characters are literally devoid of color. (The film is a satire of 1950s nostalgia as represented by that era’s all-white television sitcoms.) More regularly, however, Hollywood films that are just as white as 1950s television – from E.T. The Extra-Terrestrial(1982) to Stepmom(1998) – fail to point out their whiteness and therefore work to naturalize it as a universal state of representation.

When it goes unmentioned, whiteness is positioned as a default category, the center or the assumed norm on which everything else is based. Under this conception, white is then often defined more through what it is notthan what it is. If whiteness must remain relatively invisible, then it can only be recognized when placed in comparison to something (or someone) that is considered notwhite. For example, in the romantic comedy You’ve Got Mail, Joe (Tom Hanks) interacts with Kevin, an African American co-worker (David Chappelle). The presence of a token African American character allegedly negates any potential accusation of Hollywood racism, but his presence may also make viewers aware of racial difference – that Joe is white because he is notblack. Some of Kevin’s lines also point out Joe’s whiteness. Up until that point, however, viewers have not been encouraged to see anything racial about Joe. The subtle ideas about whiteness that are present in the film may go unnoticed by most viewers, or if they are noted during Kevin’s scene, they may be forgotten the moment he is no longer on screen.

Kevin’s friendly put-downs of Joe also reveal that whiteness is most often invisible to people who consider themselves to be white. However, many non-white individuals are often painfully aware of the dominance of whiteness, precisely because they are repeatedly excluded from its privileges. Sometimes racialized stereotypes get inverted to characterize whiteness. Thus, if people of color are stereotyped as physical and passionate, whiteness is sometimes satirized as bland and sterile, represented by processed white bread, mayonnaise, and elevator music. The stereotypes that white people lack rhythm, can’t dance, or can’t play basketball (as the title of the film White Men Can’t Jump[1992] would have it) are simply reversals of racist stereotypes that assert that people of color are “naturally” more in touch with their physicality than are white people. Many of these stereotypes seem to invoke (and probably evolved from) the racist beliefs of earlier eras. One such belief was the assumption that white people were a more evolved type of human being – and thus suited for mental and intellectual tasks – while non-white people were thought of as being more basely physical and even animalistic.

This process of defining one group against another is sometimes referred to as Othering. More specifically, Othering refers to the way a dominant culture ascribes an undesirable trait (one shared by all humans) onto one specific group of people. Psychologically, Othering depends on the defense mechanism of displacement, in which a person or group sees something about itself that it doesn’t like, and instead of accepting that fault or shortcoming, projects it onto another person or group. For example, white culture (with its Puritan and Protestant taboos against sex) has repeatedly constructed and exploited stereotypes of non-white people as being overly sexualized. Throughout US history, fear and hysteria about “rampant and animalistic” non-white sexualities (as opposed to “regulated and healthy” white sexualities) have been used to justify both institutional and individual violence against non-white people. Other character traits common to all human groups – such as laziness, greed, or criminality – are regularly denied as white traits and projected by dominant white culture onto racial or ethnic Others. In this way, and simultaneously, whiteness represents itself as moral and good, while non-white groups are frequently characterized as immoral or inferior.

The process of Othering reveals more about white frames of mind than about the various minority cultures being represented. This was often embodied within classical Hollywood filmmaking, when racial or ethnic minority characters were played by white actors. This common practice allowed white producers to construct images of non-white people according to how they (the white producers) thought non-white people acted and spoke. How non-white Others helped to define whiteness can also be seen in the silent and classical Hollywood practice of using minority-group performers to play a variety of racial or ethnic characters. For example, African Americans and Latinos were often hired to play Native American characters, and Hispanic, Italian, and Jewish actors played everything from Eskimos to Swedes. Such casting practices again reinforce the notion that people are either white or non-white, and Hollywood did not take much care to distinguish among non-white peoples, often treating them as interchangeable Others.

In socially constructing this concept of whiteness, Western culture had to define who got to be considered white. Many attempts were made over the past centuries to “measure” a person’s whiteness. In the United States, laws were passed defining who was and who was not to be considered white. People claimed that “one drop of blood” from a non-white lineage excluded an individual from being “truly” white. Marriages were carefully arranged to keep a family lineage “pure,” and laws prohibiting interracial marriage were common in most states. If there were non-white relationships within a family tree, they would frequently be hidden or denied. Throughout much of American history, lynching – the illegal mob torture and murder of a suspected individual – was a white community crime commonly spurred by fears over interracial sex. All these measures to “protect” whiteness indicate a serious cultural anxiety about the permeable borders between white and non-white races. In reality, the sexual commingling of different racial and ethnic groups was common in the United States almost from the moment European settlers landed on the continent. On the Western frontier, white men often took up relations with Native American women. In the Eastern United States, many white slave owners regularly forced sex upon their female slaves. Even President Thomas Jefferson fathered children by his slave, Sally Hemings. Needless to say, these incidents have rarely been represented in Hollywood cinema.

Struggles over the definition of whiteness were especially pronounced during the 1800s and the early 1900s, when film was in its infancy. The idea of the American melting pot arose during this period. The metaphor expressed the way various immigrant cultures and traditions were to be forged or melted together into an overall sense of American identity. Obviously, the American melting pot most readily accepted those groups that could successfully blend into or assimilate into the ideals and assumptions of white patriarchal capitalism. Assimilation was (and is) easier for some groups than for others, and the reason for that was (and is) based on longstanding notions about racial difference. European immigrants, although from different national and ethnic cultures, were more readily assimilated into mainstream white American culture than were people of African, Asian, or Native American backgrounds. Partly this was because European immigrants had a certain amount of cultural, racial, and religious overlap with white America; people from other areas of the globe were (and still are) more likely to be considered as racially and culturally Other. Nonetheless, even European immigrants had to struggle for acceptance in the United States, and a history of those struggles can be found in that era’s cinematic record.

Assimilation remains a contested issue to this day. While many people (of all racial, ethnic, and national backgrounds) support the idea that Americans should strive to assimilate into the dominant (white) way of life, others find that proposition disturbing. Some people feel that racial and ethnic cultures should be celebrated and not phased out of existence, arguing that one of the basic strengths of America is its very diversity of cultures, and – hopefully – cinematic representations. Another controversial issue related to assimilation is the phenomenon of passing, wherein some people of color deny their racial or ethnic backgrounds in order to be accepted as white. People who pass are sometimes accused of “selling out” their racial or ethnic heritages. However, people who can pass often choose to do so precisely because whites are still afforded more privilege and power in our national culture, and those who pass often want to share in those opportunities. It is this social reality that led many European immigrants to work toward assimilation and acceptance as being white. That process can be seen occurring in American films made throughout the twentieth century, especially in regard to changing representations of Irish, Italian, and Jewish Americans. In film and culture-at-large, the shift to whiteness occurred for these groups of people when they were no longer regarded as separate races, but rather as ethnicities or nationalities that could then be assimilated into the American concept of whiteness.

Bleaching the Green: The Irish in American Cinema

Irish people first came to the “New World” long before the United States declared its independence from Great Britain. These first Irish Americans were predominantly middle-class Protestants, and therefore somewhat similar to settlers from Great Britain, the majority of whom were also middle-class and Protestant. However, the cultural makeup of Irish immigrants changed dramatically during the 1800s. The great potato famine of the 1840s drove hundreds of thousands of Irish citizens – mainly of poor Catholic background – across the Atlantic ocean to the United States. Facing their first significant wave of immigration, many Americans reacted with fear and hostility. Conveniently forgetting their own recent resettlement from Europe, a number of American citizens rallied around the new cause of Nativism : that “America should be for Americans” and not for foreigners. Laws were passed in various states restricting immigration, denying voting rights, and prohibiting Irish American citizens from holding elective office. Speeches, newspaper editorials, and political cartoons often described Irish Americans as barely human: they were represented as small, hairy, apelike creatures with a propensity for violence, drunkenness, and unchecked sexual impulses.

Similar descriptions were used for African Americans during these years, and comparisons were often made between the two groups. Irish Americans were commonly called “white niggers” while African Americans were sometimes referred to as “smoked Irish.” Such shared discrimination at times tied the two communities together. Some people saw that the groups had a shared struggle and linked the institutional slavery of African Americans to the “wage slavery” of Irish immigrants, many of whom worked as servants in white households. Yet, more often than not, Irish American communities responded to such comparisons by distancing themselves from African Americans, in some cases through violent race riots. By strenuously denying similarities to African Americans, Irish Americans strove to be regarded as white and not black. Similarly, conceptions of Irish whiteness were dramatized on stage via the conventions of blackface, a popular theatrical tradition of the 1800s that featured white performers darkening their faces with makeup in order to perform broad, comedic stereotypes of African Americans. Blackface was one way that popular culture distinguished between white and non-white behaviors and identities. By leading the blackface trend, Irish American performers did acknowledge on some level how many people conflated the two groups. These performers thus positioned themselves as whitepeople who needed to “black up” to play the parts, defining themselves against a racial Other of blackness. In so doing, Irish American performers promoted their own whiteness, in effect saying “you may consider us lesser, but at least we are not black.”

Representations of Irish Americans in early American cinema drew upon already-established stereotypes and misconceptions developed in other media such as literature, newspaper cartooning, and the theater. Alternatively referred to as “Paddy,” the “Boy-o,” or the “Mick,” early films typically showed Irish Americans as small, fiery-tempered, heavy-drinking, working-class men. Irish American women also appeared in many early films, typically as ill-bred, unintelligent house servants, often named Bridget. The Finish of Bridget McKeen(1901) serves as a good example of these early cinematic representations: Bridget is a stout, slovenly scullery maid who tries to light an oven, and in her frustration stokes it with kerosene. When she lights a match, an explosion results, and the film dissolves to its supposedly uproarious punch line: a shot of Bridget’s gravestone. Yet these derogatory images of Irish Americans were short-lived, for by the advent of early cinema, public perceptions about Irish Americans were shifting. Irish Americans had been assimilating into American whiteness for half a century, and by the early 1900s, new waves of immigrants from other countries began to inundate the United States. Many of these immigrants originated from Southern and Eastern Europe, and many Americans regarded these new immigrants as darker or more swarthy (that is, less white) than immigrants from Northern and Western Europe. The Irish suddenly seemed more white in comparison.

Irish Americans began to be positioned as exemplars of immigrant assimilation, a group upon whom other immigrants should attempt to model themselves. Increasingly, the Irish were regarded as an ethnicity and a nationality, whereas they had previously been considered a race. As a consequence, Irish Americans (and their cinematic representations) moved up the scale of whiteness. Images of drunken, boisterous Micks still occurred throughout the 1920s – on stage in the long-running Abie’s Irish Rose, and on film in The Callahans and the Murphys(1927). However, the predominant image of the Irish American in 1920s film shifted to that of the Colleen. Replacing the slovenly, stupid Bridget, Colleen was a spunky, bright-eyed young woman who was quickly welcomed into American life; films about Colleen characters often ended in her marriage to a wealthy white man. Films such as Come On Over(1922), Little Annie Rooney(1925), and Irene(1926, based on the stage musical) center on young Irish American women, who, under the direction of white masculinity, successfully blend into the country’s melting pot. Often these films dramatized assimilation as an issue of generational difference: in them, parents who embodied the old Mick and Bridget stereotypes were shown to be less capable of assimilation than were their more Americanized offspring.

A number of the actresses who played these Colleen roles (such as Colleen Moore, Mary Pickford, and Nancy Carroll) were themselves of Irish heritage. Just as the stage had been one of the arenas in which Irish Americans “became” white, so did the Hollywood film industry help Irish Americans assimilate into whiteness. Unlike many other ethnic groups during the first half of the twentieth century, most Irish Americans actors did not feel the need to Anglicize their names – George O’Brien, Sally O’Neil, Maureen O’Sullivan, and Mickey Rooney (to name just a few) became stars under their own names. Irish American men also found work behind the camera as directors: Mickey Neilan, Raoul Walsh, and John Ford were all well-established directors by the end of the silent film era. Furthermore, one of the first Irish American millionaires, Joseph P. Kennedy, became himself a film executive, producing films for Gloria Swanson in the late 1920s and helping found the RKO Radio studio in 1928.

In the 1930s, a few gangster films would acknowledge Irish Americans in organized crime. Based on real-life criminals “Machine Gun” Kelly and “Baby Face” Nelson, these thugs portrayed by actor James Cagney might have presaged an anti-Irish backlash. Yet films centered on Irish American hoodlums were invariably balanced by those that portrayed Irish Americans as law-abiding citizens. For example, Cagney’s gangster character in Public Enemy(1931) has a policeman brother, and his character in Angels With Dirty Faces(1938) has a priest for a best friend. Cagney’s career itself dramatized Irish American assimilation into whiteness: his roles evolved from rebel outsiders to all-American heroes. By 1940, he was starring in The Fighting 69th, a film about a famed Irish American regiment that fought in World War I. Two years later, Cagney won an Oscar for playing the flag-waving Irish American showman George M. Cohan in Yankee Doodle Dandy(1942).

Irish Americans in film (and in real life) worked hard to assimilate through overt indications of patriotism and loyalty. Irish Americans came to dominate urban police forces and fire departments, and many joined the armed forces. Overt displays of Irish American patriotism were made in the movies as well. John Ford became known for directing films that glorified the United States – primarily his legendary Westerns, but also a number of overtly patriotic war films during World War II. In both types of films, Irish American characters consistently appeared as true-blue Americans. Picturing Irish Americans as ultra-nationalists often went hand in hand with seeing them as pious and moral, specifically by linking them to Catholicism. By the 1940s, the most common image of Irish Americans in Hollywood films was either as policeman or as priest. Films such as Boys Town(1938), Angels With Dirty Faces, the Oscar-winning Going My Way(1944), its sequel The Bells of St. Mary’s(1945), and Fighting Father Dunne(1948) showed Irish American priests kindly dispensing wisdom and morality to future generations. This image of Irish Americans as upholders of American moral rectitude extended to the industry itself. The Hollywood Production Code was written in 1930 by two Irish Americans, Martin Quigley and Jesuit Fr. Daniel Lord. When the Catholic Church organized the Legion of Decency to protest against violent and sexually licentious Hollywood films, Irish American priests led the way. And when the Production Code Administration responded in 1934 by instituting the Seal of Approval provision that enforced the Code, Irish American Joseph Breen helmed the organization (and did so for the next 20 years). Picturing Irish Americans as moral guardians possibly reached its apex with the short-lived popularity of Senator Joseph McCarthy, a politician who exploited the Red Scare by pursuing potential communist agents in the United States.

When McCarthy’s popularity diminished in the mid-1950s, the Production Code Administration’s power was also beginning to wane. While one might suppose this to signal a loss of Irish American influence on Hollywood film, the 1950s also seemed to signal the end of Irish American struggles for inclusion. By the end of World War II, the Irish American population had largely been assimilated. Evidence of this was plain on American movie screens: actors of Irish heritage regularly played a variety of roles instead of being typecast as only Irish characters. For example, in the 1940s, Gene Kelly had often played overtly Irish American characters, but by the 1950s, his characters were considered simply American. He was, after all, An American in Paris(1951), not an Irish Americanin Paris. A few years later, Bing Crosby and Grace Kelly, both of Irish descent, starred as the epitome of upper-class white culture in High Society(1956). Even in a film aboutIreland and Irish immigration, one can find successful assimilation dramatized. For example, in John Ford’s Oscar-winning The Quiet Man(1952), John Wayne plays an Irish American so thoroughly assimilated to American whiteness that he has difficulty coping with the culture and people of Ireland itself. The election of President John F. Kennedy in 1960 might be said to symbolize the pinnacle of Irish American assimilation, although there were still many Americans who were outspokenly prejudiced against his Irish heritage, as well as his Catholicism.

Going My Way(1944) told the story of two generations of Irish American priests – the older (Barry Fitzgerald) portrayed in broad fashion, and the younger (Bing Crosby) as almost thoroughly assimilated.

Going My Way, copyright © 1944, Paramount

Many Irish Americans today still strongly hold onto their ethnic heritage and identity, as can be seen across the country every St Patrick’s Day. Being white and being Irish are no longer incompatible, though, as the common phrase “everyone’s Irish on St Patrick’s Day” attests. Irish Americans today can choose to proclaim their ethnicity or to blend into an undifferentiated whiteness. This status is evident in the way Irish Americans have been shown in Hollywood films since the 1960s. Explicitly ethnic Irish Americans surface only sporadically – often in nostalgic period films like The Sting(1973), Miller’s Crossing(1991), or The Road to Perdition(2002). Gangs of New York(2002) is one of the few films that acknowledges what Irish Americans endured in the struggle for acceptance into whiteness during the 1800s. The social and political problems faced by Ireland itself have been the subject of several Irish, British, and American films, including The Crying Game(1992), In the Name of the Father(1993), Michael Collins(1996), and Angela’s Ashes(1999). However, many more Irish American characters appear in Hollywood films in ways that are indistinguishable from any other white characters. When audiences watched Saving Private Ryan(1998), most probably did not even consciously think about the title character being Irish American. He was simply a white American soldier.

John Ford’s The Quiet Man(1952) showed John Wayne’s Irish American attempting to assimilate when he moves to Ireland (and win the heart of Maureen O’Hara’s local lass).

The Quiet Man, copyright © 1952, Republic

Looking for Respect: Italians in American Cinema

During the early 1800s, Italian people emigrated to America in relatively small numbers. However, many Italians (along with Poles, Slavs, Russians, Greeks, and other people from Southern and Eastern Europe) were part of a great surge in immigration that occurred in America during the final years of the nineteenth century. According to some sources, by 1900, 75 percent of the population of major urban areas (including New York City, Chicago, and Boston) were made up of immigrants. This influx of people produced a new round of xenophobia, the irrational fear and/or hatred of foreigners, among many Americans. Much as Irish immigrants had been compared to and equated with African Americans a few decades earlier, so too were Italian immigrants thought by some to be “black.” Conventional representations of Italian Americans in newspapers and early films depicted them as having darker skin tones, thick curly hair, and little to no education. Consequently, while Irish Americans were slowly coming to be regarded as white during the silent film era, Italian Americans were just beginning their own struggle for assimilation. Furthermore, Italian Americans themselves were sometimes prejudiced against other Italian Americans. Until the late 1800s, Italy was not a unified nation but a collection of separate principalities – thus many Italian immigrants had a stronger regional than national identity. Not all people from mainland Italy liked being compared to those from Sicily (and vice versa), although the popular media of the day often used the same stereotypes to represent people from both regions.

One of the earliest of those stereotypical representations (in newspapers, theater, and film) was that of an assimilationist small businessman. Sometimes named Luigi, or Carmine, or Guido, this Italian American stereotype was a simple-minded, working-class man who spoke in broken English and who often wore a bushy moustache. He was always smiling and gracious, and he worked as a street vendor, cranked a street organ, or ran a small café in order to support his large family. This stereotype continued to be a recognizable stock character throughout decades of Hollywood film. He appears as a friendly restaurateur, small business owner, or fruit-stand manager in countless small roles in countless Hollywood films. The type was so prevalent that one of the Marx Brothers (who were of Russian and Jewish heritage) became famous for his Italian American persona “Chico.” The type was also popular on radio (and later television) programs such as Life with Luigi(CBSTV, 1952–3). To this day, the name “Guido” is sometimes used to describe a young, none-too-bright Italian American working-class man, as in the film Kiss Me Guido(1997). The stereotype is also invoked by the video-game (and film) characters, the Super Mario Brothers(1993).

While the Luigi or Guido figure was somewhat simple-minded, he was at least non-threatening, and seemed to indicate that Italian Americans could eventually be assimilated into American whiteness via their hard work and capitalist ethics. However, there was another more ominous Italian American stereotype present in the public consciousness during the first decades of the twentieth century: that of the socialist radical or anarchist. An anarchist is someone who believes in toppling all forms of social control and/or government, often through violent means. The Italian American anarchist type (sometimes he was also depicted as coming from neighboring Southern or Eastern European countries) actively battled againstwhite America rather than trying to assimilate into it. In films of the era, this dark-skinned antagonist was defeated by heroic white men.

By the 1920s, yet another image of Italian American men could be found on the nation’s movie screens: the Latin Lover, a handsome and exotic, sexually alluring leading man. The most famous Latin Lover of the decade was Rudolph Valentino, an actor who had been born in Italy and who appeared in films such as The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse(1921) and The Sheik(1921). While the ascendancy of Valentino and the Latin Lover type may be seen as a step toward acceptance and assimilation, the appeal of the Latin Lover lies precisely in his Otherness. He is bold, aggressive, and potentially violent in his sexual passions – quite unlike respectable white men. Furthermore, as will be discussed in chapter 7, the Latin Lover type also included men from Hispanic cultures – a fact that again suggests how the dominant culture groups together different racial/ethnic Others as a means of opposing (and therefore defining) whiteness. The Latin Lover image was also used in more forthrightly derogative ways, as when he was represented as a gigolo trying to sleep his way into wealth and white society.

By the early 1930s, the image of the Italian American man looking for success and respect via disreputable means took a more ominous turn on the nation’s movie screens. Italian Americans became the ruthless lead characters of the gangster film. Partly, this linkage of Italian Americans and mobsters was drawn from real life. Stories of Italian American ghettoes being controlled by almost feudal family gangs (the so-called Mafia, a concept originally derived from Sicilian culture) had begun to proliferate in the American popular press in the earliest years of the century. During the Prohibition era (1919–33), various criminal organizations thrived by distributing illegal alcohol. While people of numerous backgrounds were part of these organized crimes, many people focused on the Italian names being reported in the nation’s newspapers: Al Capone, Frank Nitti, Johnny Torrio, etc. Thus, when Hollywood began its cycle of gangster films in the early 1930s, Italian Americans were prominently featured. Little Caesar(1930), a film that many regard as the first film of this genre, focuses on the rise and fall of Italian American gangster Rico Bandello (played by Jewish actor Edward G. Robinson). Little Caesarwas followed by Scarface(1932), which focuses on the corrupt, ultra-violent, and vaguely incestuous Tony Camonte (played by another Jewish actor, Paul Muni). Throughout the 1930s and continuing for decades, the most conspicuous representation of Italian Americans on Hollywood movie screens would be as mobsters.

Other stereotypical and more fully developed Italian American characters began to emerge during and after World War II. As the United States fought a war against Germany, Italy, and Japan, Italian Americans increasingly promoted their patriotism and loyalty to America. As a consequence, they were often featured in Hollywood’s wartime propaganda movies. In the many war movies made during these years, such as Sahara(1943), The Purple Heart(1944), Back to Bataan(1945), and The Story of G.I. Joe(1945), Italian American characters were included; they fought with courage and dedication alongside American soldiers of a variety of other ethnicities. In the postwar years, Italian American musical performers such as Frank Sinatra, Dean Martin, and Mario Lanza became increasingly popular, both on radio and in Hollywood films.

Postwar filmmaking in Italy also had an affect on Hollywood images of Italian Americans. The popularity and critical regard of the film movement known as Italian Neorealism spurred greater attempts at cinematic realism in a number of countries; the movement regularly represented Italians as poor and/or working-class people. Consequently, 1950s American film also saw an increase in down-to-earth, working-class Italian American characters. Part of this “earthiness” expressed itself via sensuality. Italian actresses such as Sophia Loren, Gina Lollobrigida, and Anna Magnani became internationally famous during these years, partly because of their uninhibited sexuality. Like that of the 1920s Latin Lover, the sexual appeal these women exuded for American audiences was partly due to their Otherness. (The fact that many of their films were made overseas – far away from the Hollywood Production Code – also contributed to their reputation as sexually unbridled.) Earthy, working-class representations of Italian Americans became so popular that they swept the Oscars in 1955, when a film about a lonely Italian American butcher (Marty) won Best Picture and Best Actor (Ernest Borgnine), and Anna Magnani won a Best Actress award for her first American film, The Rose Tattoo.

Edward G. Robinson played Italian American mobster Rico Bandello in one of the most famous classical Hollywood gangster movies,

Little Caesar(1930). Little Caesar, copyright © 1930, Warner Bros.

During the 1960s and 1970s, a new generation of Italian American actors and directors became prominent in the Hollywood film industry. Actors such as Al Pacino, Robert DeNiro, Talia Shire, Sylvester Stallone, and John Travolta rose to prominence, while directors like Francis Ford Coppola, Martin Scorsese, and Michael Cimino were also highly successful. While such success might possibly signal an erasure of Italian ethnicity into a general sense of whiteness, this was not the case. Recall that during the 1960s, dominant American culture was coming under severe criticism from various sectors of the counterculture. As part of those critiques, whiteness was being taken off its pedestal and racial and ethnic identities were being celebrated as more authentic and meaningful. White suburban lifestyles (on display, for example, in comedies such as Please Don’t Eat the Daisies[1960] or The Thrill Of It All[1963]) were increasingly seen as bland and mind-numbing. As a consequence, ethnicity was suddenly “in,” and starched symbols of whiteness (such as Doris Day and John Wayne) were supplanted by actors who did not hide their ethnic heritage.

Yet what types of stories and characters did these new Italian American filmmakers create? To a great extent, they replicated old-style Hollywood formulas in nostalgic Hollywood blockbusters. One of the first and most important of these films was Francis Ford Coppola’s The Godfather(1972), a period gangster film about Italian American mobsters. While the film was protested against by many Italian American media watchdog groups who objected to the revival of the gangster stereotype, it became one of the most successful films of all time, spawning two sequels (1974 and 1990). Many of Martin Scorsese’s films also centered on Italian American gangs and gangsters. Although he has made all sorts of films, including a personal documentary about his parents and their ethnic heritage (Italianamerican[1974]), it is Scorsese’s violent gangster films that most moviegoers recall: Mean Streets(1973), Goodfellas(1990), and Casino(1995). Still other films from this era (reworking another earlier stereotype) focus on Italian American working-class men who struggle to achieve the American Dream. Rocky(1976) and Saturday Night Fever(1977) both position their Italian American protagonists not just as characters representative of Italian American concerns, but also as larger symbols of American spirit and determination. Similarly, Coppola had envisioned the Corleone family in The Godfatherto be a symbol of America – but not in the patriotic style of Rocky. Rather, Coppola used his Godfatherfilms (especially Part II[1974]) to indict and critique white patriarchal capitalism.

Even in the New Hollywood, filmmakers still associated Italian American culture and tradition with the mobster stereotype, particularly in the enormously successful The Godfather(1972).

The Godfather, copyright © 1972, Paramount

Many of these types of images of Italian Americans remain in contemporary Hollywood film. While characters of Irish descent often appear without any mention of their heritage, Italian American characters are still frequently depicted as earthy, working-class types (as in Moonstruck[1988]), or mobsters (as in The Untouchables[1988] or the cable TV series The Sopranos[1999–2007]). While across culture-at-large Italian Americans have become for the most part regarded as white, many Italian Americans still choose to maintain a pronounced ethnicity, actively celebrating the culture and traditions of their heritage. Consequently, representing Italian Americans as a distinct ethnicity remains a common practice in American film.

A Special Case: Jews and Hollywood

Jews in America and in American cinema have faced (and still do face) a different set of circumstances than either Irish Americans or Italian Americans in their negotiation of whiteness. For example, being Jewish frequently encompasses religion as well as ethnicity. Also, Jewish immigrants came to America from a wide variety of countries and thus claim a wide range of national heritages. Unlike most Irish and Italian people, who left their native lands for America as a matter of choice, many Jews were forced out of European nations via state-sanctioned acts of murder and terrorism (such as the pogroms of Tsarist Russia or the Nazi-induced Holocaust). Furthermore, while most of the US population now regards citizens of European Jewish background to be white, a small but highly vocal group of white supremacist Americans still regard Jews as a “race” that are out to destroy white Aryan purity through intermarriage. (Their use of the term “race,” rather than “ethnicity,” is further meant to exclude Jews from their definition of whiteness.) The roots of such anti-Semitism, or hatred of Jews, are complex and can be traced back thousands of years. Even in contemporary America, people of Jewish heritage are still regularly targeted by hate crimes and hate speech. Conversely, most European immigrants from Christian belief systems have been more readily assimilated into the ideals of American whiteness.

Anti-Semitism was an even stronger force in the United States during the first half of the twentieth century. One can see this in films made during the earliest days of cinema, before the advent of Hollywood. Short films made by white Protestant men (such as those who worked for Thomas Edison) sometimes featured grotesque stereotypes of Jews as hunchbacked, hook-nosed, and greedy cheats. Such subhuman depictions, found in films like Levitsky’s Insurance Policy(1903) and Cohen’s Advertising Scheme(1904), presented an image of Jews as money-grubbing and untrustworthy. Jewish immigrants of the era responded in different manners to anti-Semitic attitudes and representations. As with other ethnic groups, some Jews drew in closer to each other in urban ghettoes, where they fiercely clung to their traditions. Examples of this philosophy can be found in a number of Yiddish-language films made during the 1920s and 1930s. These films were small-budget, independent films made by and for the Jewish community and were rarely shown outside urban neighborhood theaters. On the other hand, many Jewish immigrants struggled to assimilate into the culture of white Christian America. (Interestingly, the term “American melting pot” itself was coined by a Jewish immigrant playwright, Israel Zangwill.) Also, just as Irish American theatrical performers had done, a number of Jewish American performers began donning blackface on stage, an act that emphasized that Jews were indeed white people who had to “black up” in order to play African Americans.

Intriguingly, many of the most popular Jewish stage entertainers of the period used blackface in complex ways. While attempting to differentiate (white) Jews from (black) African Americans, Jewish entertainers also used blackface to indicate shared oppression and outsider status. For example, under the guise of blackface, Jewish entertainers sometimes felt safe to tell critical jokes about the white power structure. Jewish entertainers also blurred boundaries between racial and ethnic categories – they may have been performing in blackface, but they sprinkled their dialog with Yiddish slang. Such tomfoolery, practiced by major stars such as Al Jolson and Eddie Cantor, tended to expose the artificiality of racial and ethnic categories by jumbling them all together. When Eddie Cantor made a film version of his hit stage musical Whoopee!(1930), he bounced from one racial/ethnic type to another: Jewish in one scene, then in blackface, and then Native American. The film’s story revolves around Cantor’s friends, who are forbidden to marry because the man is Native American and the woman is white. This conflict is resolved when it is discovered that the male was only raised by Native Americans and is “actually” white. The resolution of the plot, as well as Cantor’s parody of racial stereotypes, demonstrate the highly subjective and constantly fluctuating nature of racial and ethnic identities.

By the time that Al Jolson and Eddie Cantor moved from stage to film, circumstances for Jews in the American film industry had changed immensely. During the 1920s, Jews came to dominate Hollywood. Initially, a number of Jewish immigrants had opened and run nickelodeons in the urban ghettoes of large Eastern cities. From those beginnings, these same men built film production companies, moved to the West Coast, and wrested control of the industry away from Eastern entrepreneurs like Thomas Edison. Most of the heads of the major studios during the classical Hollywood era were Jewish: Carl Laemmle (Universal), Adolph Zukor (Paramount), Louis B. Mayer (MGM), Harry Cohn (Columbia), and the Warner Brothers. With Jewish men as the leaders of the film industry, many other people of Jewish heritage went into the business as directors, writers, actors, and technicians. Consequently, American Jews have had a greater say in how their images were being fashioned in American cinema than any other racial or ethnic minority.

This is not to say that mainstream Hollywood movies became non-stop celebrations of Jewish culture. On the contrary, Jewish filmmakers had to negotiate their images (both as industry leaders and in film texts) within a larger white society. Classical Hollywood films therefore emphasized a vision of America as largely white and Christian, in order to appeal to white mainstream audiences and avoid the wrath of potential anti-Semites. For example, there are numerous fondly remembered classical Hollywood Christmas films (A Christmas Carol[1938], It’s A Wonderful Life[1946], Miracle On 34th Street[1947]) but, until 8 Crazy Nights(2002), there were no comparable Hollywood Hanukkah films. In fact, overtly Jewish characters rarely appeared in 1930s Hollywood films, and Jewish executives often went out of their way to efface their (and their employees’) Jewish heritage. Jewish actors were encouraged to change their names to “whiter-sounding” ones: Emanuel Goldenberg, Julius Garfinkle, Betty Perske, Danielovitch Demsky, David Kaminsky, and Bernard Schwartz became, respectively, Edward G. Robinson, John Garfield, Lauren Bacall, Kirk Douglas, Danny Kaye, and Tony Curtis. These efforts were a conscious strategy to deal with recurrent worries about anti-Semitism. Repeatedly, Christian protest and reform groups asserted that Jews in Hollywood were destroying the moral fiber of the country. Jews in Hollywood were constantly on the defensive, ready for the shadow of prejudice to emerge and attempt to destroy their industry. It is no wonder that producer David O. Selznick (most famous for producing Gone With the Wind[1939]) told an interviewer at one point, “I’m American and not a Jew.”

Possibly the one studio to show some commitment to upholding its Jewish heritage was Warner Brothers. Consistently hiring more Jewish actors than did other studios, Warner Brothers also made films about Jewish characters on a somewhat regular basis. The studio won a Best Picture Oscar for The Life of Emile Zola(1937), a film that focused on the notorious “Dreyfus affair,” a major French military trial that pivoted on anti-Semitism. Warner Brothers was also the first studio to repudiate Nazi Germany in its films, several years before the United States entered World War II, most memorably in Confessions of a Nazi Spy(1939). Executives at the other studios refrained from making films critical of Nazi Germany so that they could maintain their European film distribution deals. While these decisions were thus partly fueled by capitalist desires, Jewish industry heads were also worried that taking a forthright stand against Hitler could reawaken anti-Semitic sentiment against Hollywood. In fact, that is exactly what happened in the wake of films like Confessions of a Nazi Spy. Special US Senate committee hearings were held, accusing Hollywood of trying to push the United States into World War II. The transcripts of these hearings are filled with ugly anti-Semitic rhetoric, a good example of how pervasive (and acceptable) such feelings were during this era.

After the war, as American citizens learned the extent of the Holocaust, reevaluations of American anti-Semitism began to occur. Yet many Jewish Hollywood moguls feared tackling the subject. It took the one non-Jewish studio head (Darryl F. Zanuck at 20th Century-Fox) to make the first social problem film about American anti-Semitism. Gentleman’s Agreement(1947) starred Gregory Peck as a gentile reporter going undercover as a Jew in order to expose prejudice. The film was a critical and commercial success, and won a Best Picture Oscar. That same year, a film about an anti-Semitic murder, Crossfire(1947), was released. Sadly, many of the people involved in making it were soon targets of suspicion and hatred themselves. Director Edward Dmytryk and actor Sam Levene (along with many other Jewish people in the film industry) were accused of being communist agents by HUAC, the House Un-American Activities Committee. The ensuing Red Scare threw studio executives into a panic. These allegations of communist influence in Hollywood were again tinged with (and, some have argued, fueled by) the anti-Semitism of prominent politicians and social commentators. The results of this postwar paranoia did put a disproportionate amount of Jews in Hollywood out of work. Fear of being considered un-American also curtailed the production of social problem films. Images of Jews in Hollywood films did not disappear in the wake of the Red Scare, but they were now rarely shown as part of present-day America. Rather, Hollywood films of the 1950s tended to represent Jews as oppressed minorities in Biblical epics such as The Ten Commandments(1956) and Ben-Hur(1959). These films addressed social prejudice, but from a safe historical distance and within the framework of mainstream Christianity.

Case Study: The Jazz Singer(1927)

The Jazz Singerstands as one of the most important movies in American film history because it is considered to be the first Hollywood studio motion picture feature with synchronized sound. Produced by Warner Brothers in 1927, this silent film with sound sequences revolutionized the industry; it also deals with issues of race and ethnicity in very interesting ways. The story of The Jazz Singerfocuses on the problems faced by Jewish immigrants in the first few decades of the twentieth century, and dramatizes the process of ethnic assimilation into whiteness. The film also points out historical connections between Jewish immigrants and African Americans (primarily via the blackface tradition), and even obliquely comments on the connections between Jews and Irish Americans.

As a way to foreground the use of sound, The Jazz Singeris fundamentally about two different types of music: liturgical sacred music and modern American popular song (under the catch-all term “jazz”). Jakie Rabinowitz (Al Jolson) has been trained by his father to follow in his profession: all the men in the Rabinowitz family have been cantors, men who lead a synagogue’s congregation in sung prayer. Jakie, however, as a second-generation American Jew exposed to the American melting pot’s wealth of new rhythms and melodies, prefers to sing jazz. His father becomes angry that his son is seemingly forsaking the music of his Jewish heritage for American jazz. (In one inventive sequence, while Jakie is singing “Blue Skies,” his father comes in and shouts “Stop!”; just at that point, the film switches from a sound sequence back into a silent film.) Forced to choose between the two types of music and the cultures they represent, Jakie runs away from home and tries his luck singing on stage. Jakie’s interest in leaving behind his heritage in favor of American popular music indicates his aptitude for assimilation. As part of that trend, Jakie Rabinowitz changes his name to Jack Robin – in effect erasing his Jewish identity (his minority-ethnic-sounding name) for a more nondescript white-sounding name, just as many other Jewish actors in show business were being encouraged to do.

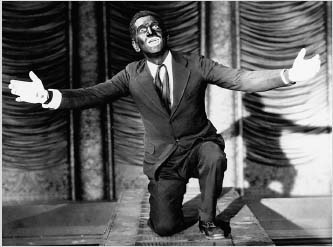

Al Jolson in blackface as Jake Rabinowitz/Jack Robin in his most famous role, The Jazz Singer(1927).

The Jazz Singer, copyright © 1927, Warner Bros.

Intriguingly, the person who guides Jack to stardom is fellow stage performer Mary Dale. Mary actively attempts to usher Jack into the inner circle of assimilated whiteness, by helping him move up the ladder of theatrical success. The character of Mary Dale is enacted by “reallife” Irish American actress May McAvoy, who played the Colleen type in many 1920s movies. While she kept her Irish-sounding name, McAvoy was accepted as white, and in playing this role, she embodies a successful example of Irish American assimilation. Most audiences today would probably not even think of her character as Irish. Mary Dale/May McAvoy literally personifies the whiteness that Jack is moving toward. During the one moment in the film in which we see May perform on stage, she is wearing a fluffy white tutu and a peroxide wig that makes her hair appear to be gleaming white, literally a vision of whiteness.

On the other hand, Jack’s big chance on Broadway is tied to his performing in blackface, simultaneously emphasizing his difference from African Americans andthe similarities in their marginal racial/ethnic status. Star Al Jolson was himself renowned for his blackface act. Yet the film does not introduce blackface until a key point in the story. Jack is just about to perform his final dress rehearsal before opening night on Broadway when he finds out that his father is dying and wants his son to take his place as cantor. The film draws out the emotional tug-of-war going on in Jack as he grapples with the lure of stardom/assimilation and his love of and sense of obligation to his Jewish upbringing. It is at this moment, as Jack is suffering through this turmoil, that he puts on blackface. The sadness and sense of difference he feels become linked to his transformation into an African American stereotype. In one shot, Jack/Jakie looks sadly in the mirror at himself in blackface, and his reflection dissolves to a vision of his father as cantor. The superimposition of the two images further strengthens the sense of Jewish blackface performance as somehow expressive of an outsider status.

The film resolves these tensions when Jakie decides to sing for his father instead of appearing on opening night – yet by the next season Jack Robin has nonetheless become a star on Broadway. The film does not bother to explain how this came to be, even though Mary and the show’s producer had told Jack that he would be finished in show business if he opted for his father instead of the play. Yet, in typical Hollywood “happy-ending” style, Jack has been able to hold onto his Jewish heritage and stillassimilate. A more consistent motif of the film that expresses the same idea is, again, tied to sound. Many people tell Jack that, unlike the average jazz singer, he sings “with a tear in his voice,” a description of his singing that associates his uniqueness directly with his training as a Jewish cantor. Jack is a better singer becauseof his ethnic heritage, even as he must assimilate to some degree in order to find acceptance. Produced by American Jews in Hollywood, The Jazz Singerendorses Jewish assimilation into whiteness, but not by necessarily denying Jewish identity in the process.

Contemporary Jewish American characters returned to American films during the 1960s. Just as the countercultural critique of whiteness resulted in a new generation of Italian American film actors, so too did a number of Jewish American performers become stars at this time: Barbra Streisand, Elliot Gould, Dustin Hoffman, Woody Allen. However, unlike their counterparts of earlier generations, these actors did not have to efface their Jewish identity by changing their names, revamping their looks, or playing only Christian characters. Today, Jewish Americans remain a strong presence in the film industry, and most of them no longer fear the possibility of anti-Semitic backlashes. While many Jewish filmmakers still focus on stories and issues central to white Christian America, there is ever-greater room for films about the Jewish American experience or films that center on issues of historical importance, such as Schindler’s List(1993) or Focus(2001). Some contemporary films, like Keeping Up With the Steins(2006), use gentle humor to celebrate the peccadilloes of Jewish American culture and/or American ethnicities in general. Similarly, the romantic comedy Keeping the Faith(2000) starred Ben Stiller as a rabbi, Edward Norton as an Irish American priest, and Jenna Elfman as the woman torn between them. The film acknowledges many of our contemporary culture’s ethnic and religious differences with humor and sensitivity.

While such developments seem to indicate that Jewish Americans have largely been accepted as white, anti-Semitism continues to be kept alive within various white supremacist groups and fundamentalist Christian communities. The survival of demonic Jewish stereotypes was made vividly clear with the release (and enormous box office success) of The Passion of the Christ(2004). This harrowing retelling of Jesus Christ’s torture and crucifixion, directed by Mel Gibson, acknowledges that both Romans and Jews were involved in his death, yet presents his Jewish persecutors as the more twisted and grotesque figures. Jewish communities were aghast and protested the film across the country. And although Gibson denied any anti-Semitic intentions in his film, he was caught making anti-Semitic comments during an arrest for drunk driving in 2006. (He later issued a public apology.) Such films and incidents highlight the fact that assimilation into whiteness is a process that is always ongoing, as well as that fear and/or hatred of the Other remains a powerful force in many Americans’ lives.

Veiled and Reviled: Arabs on Film in America

Like all of the cultural groups discussed throughout this book, the five million people of Arab descent living in America today are a highly diverse group of people. They can trace their national heritages to over 20 nations that stretch across Northern Africa (such as Morocco, Libya, Egypt) and onto the Arabian Peninsula (including Lebanon, Syria, Yemen, Saudi Arabia, and Iraq). The Arab world overlaps with the Middle East, which also includes Israel, Turkey, and Iran. Often what seems to define the idea of the Middle East in Western thinking is the Arabic language and/or the Muslim religion, although there are many different languages spoken and religions practiced throughout the entire region. In fact, there are more African American Muslims in the United States than Arab American Muslims, and most Lebanese Americans identify themselves as Christians.

Much of the current strife in the Middle East is a continuation of centuries-long struggles between religions, tribes, and nations. During the Middle Ages, Christian Europeans waged war against Muslims (and others) in an attempt to claim and colonize the Holy Lands. These so-called Crusades eventually gave way to more modern forms of colonialism, wherein various European powers controlled the region, extracting material wealth and strategic advantages. The situation was exacerbated by the creation of the Jewish state of Israel by the United Nations in 1948. Israel was created by dividing the former British territory of Palestine; Palestine was mostly inhabited by Arabs, and they vehemently rejected the partitioning. Wars and armed conflict between Israel, Palestine, and Palestine’s Arab supporters immediately resulted and continue to this day. In yet other parts of the Middle East, corruption and greed for the area’s wealth and strategic location allowed for the rise of brutal dictators (Muammar Qaddafiof Libya, Saddam Hussein of Iraq), and most recently anti-Western religious extremists such as the Taliban, Hezbollah, and Al Qaeda. Much of the Middle East continues to be an unstable region filled with violent struggle, fueled by highly diverse and opposing nations, religions, cultures, and ideologies. As such, Americans of Middle Eastern descent are themselves a highly diverse group of individuals.

Intriguingly, one of the most significant things about Arab Americans onscreen in America is their relative scarcity: Hollywood has much more regularly depicted images of Middle Eastern Arabswhile nearly ignoring the presence of Arab Americans. In classical Hollywood cinema, Middle Eastern Arabs could sometimes be found interacting with British or French protagonists (as soldiers, explorers, archaeologists, or tourists), images that reflected the history of European colonialism in the region. In films such as Beau Geste(1926 and 1939) and The Four Feathers(1915, 1929, 1939, and 2002), European armies battle scores of Arab tribesmen, and the films somehow make it seem as though the Arabs rather than the colonizing nations are the villainous invaders. Sultans are shown sending their armies to lay siege to the white soldiers’ fortresses, scimitars blazing and ululations rending the air to make them seem strange and terrifying. Some critics have referred to these films as “Easterns,” because their narrative tropes seem almost identical to those of the Hollywood Western, replacing bloodthirsty Indian savages with bloodthirsty Arab ones.

In other films, Arabs were sexualized figures who either enticed or otherwise served the lusts of white lead characters. Intriguingly, a number of Hollywood films show Europeans “going native” – being personally transformed by participating in Arabic culture – one aspect of Orientalist desire. As discussed more fully in chapter 6, Orientalism is the term used to describe the ways in which the West has imagined the East (including the Middle East) as an exciting, primitive, and sensual landscape, the alleged opposite and repressed Other of white Western civilization. Thus, in the incredibly popular silent film The Sheik, “Latin Lover” Rudolph Valentino plays the titular Sheik Ahmed, who forcefully and lustfully kidnaps a chaste British heiress named Diana. She is simultaneously terrified and thrilled, but their romance cannot become acceptable until it is discovered that Ahmed is actually of European lineage. Decades later, the epic Lawrence of Arabia(1962) dramatized how English soldier T. E. Lawrence (Peter O’Toole) was attracted to and eventually adopted into Arab tribes as they fought for independence from their colonizers. Similar to the sexual and racial overtones of The Sheik, there are subtle indications that Lawrence’s fascination with Arab culture is linked to both homosexual and sadomasochistic desires on his part.

Probably the most pervasive image of sexualized Arabs in Hollywood films is that of the belly dancer or harem girl. Again a function of Orientalism, the Hollywood harem is presented as an exotic Arabian Nightsfantasy wherein anything (sexual) is possible. From the early silent film A Prisoner in the Harem(1913) to the Bob Hope–Bing Crosby musical comedy The Road to Morocco(1942) to Elvis Presley in Harum Scarum(1966), harems have been a constant source of fascination for white audiences, reducing Arab women to little more than dark-skinned and sensual objects. Arab culture as a site of mysterious unbridled sexuality is even at the heart of the classical Hollywood horror film The Mummy(1932), as well as its countless sequels, remakes, and updates (even into the twenty-first century). In The Mummy, Im-Ho-Tep (played by British actor Boris Karloff) is a monstrous living-dead Egyptian prince who lusts after a Western woman who may or may not be the reincarnation of his lost love.

As noted above, rarely have Arabs been shown becoming part of the fabric of either European or American communities. There has been an attitude among many that people of Arab heritage cannot assimilate into Western society (as in the adage “East is East and West is West, and never the twain shall meet”). Just as Irish and Italian Catholic Americans were once considered unable to assimilate because they supposedly held a stronger allegiance to the pope than to the president, so too do many today assume that Arab Americans pledge allegiance to the Muslim faith and not the United States. One of the few assimilated Middle Easterners to appear in Hollywood film is the Persian peddler Ali Hakim (Eddie Albert) in Oklahoma!(1955). Yet Ali Hakim is more an all-purpose exotic character used for comic effect than a genuine expression of emigration and/or assimilation. An inflammatory representation of an unassimilated Arab American character from the same era can be found in Herschell Gordon Lewis’s cult gore film Blood Feast(1963). In it, Egyptian caterer Fuad Ramses brutally murders a string of women in order to prepare a cannibalistic feast in honor of an Egyptian deity. This linkage of sex, violence, and (non-Christian) religion continues to mark more contemporary stereotypes of Arabs and Arab Americans.

By the late 1960s, as the United States became more involved in the Middle East due to both the need for oil and support of the new nation of Israel, the old image of the sultan was reconfigured into that of the modern-day oil mogul. A small number of films included subplots about wealthy Arabs being sent to America for schooling. Although this younger generation were often pictured as enjoying American culture, their presence was more often played for comic “culture clash” shtick. For example, in John Goldfarb, Please Come Home(1965), the “Crown Prince of Fawzia” (Patrick Adiarte) tells his father King Fawz (British actor Peter Ustinov) that he has been expelled from Notre Dame because he is Arab and not Irish. Many Arab Americans have taken offense at the almost comic-book stereotypes in this film. Yet it is also possible to read this little-known comedy, written by Arab American screenwriter William Peter Blatty (who would later go on to write the novel and Oscar-winning screenplay of The Exorcist[1973]), as a parody of Arab stereotypes – as well as American foreign policy. The king creates his own football team with his guards, coached by a bumbling American pilot named John Goldfarb (Richard Crenna), and uses his connections with the US State Department to force Notre Dame to play them. Although a few Arab Americans of the era protested the film, it was the University of Notre Dame that was most upset. They sued (unsuccessfully) its studio, 20th Century-Fox, at least in part because the Arab team wins the football match!

The growing economic power of Arab nations (and resentment of them in some Americans) was exacerbated in the 1970s as OPEC (Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries) instituted a petroleum embargo, resulting in gas shortages and higher prices. Also, by the 1970s, a number of radical groups working for the liberation of Palestine or for other Arab or Muslim causes made headlines with bombings, kidnappings, and airplane hijackings, culminating in the 1979 kidnapping of 52 American hostages in Iran, who were held for more than a year. These various developments led to the rise of what has become today the most prevalent image of Arabs: the Muslim terrorist. Ever since the 1970s, Arab terrorists have become an easy cliché in action films like The Delta Force(1986), Executive Decision(1996),

G.I. Jane (1997), and Rules of Engagement(2000). While often these films show white American heroes battling Arabs in foreign lands, Arab terrorists have also been shown “infiltrating” (as opposed to assimilating) into US society in order to bring it down. Black Sunday(1977), for example, shows a Palestinian terrorist plotting to hijack the Goodyear Blimp and hold the Super Bowl hostage. Other Arab terrorists in the US factor into films as diverse as Back to the Future(1985), True Lies(1994), and The Siege(1998). The Siegeis a curious film. While it presents Arab Americans as terrorists, it also includes an Arab American FBI agent. Furthermore, the film eerily presages the aftermath of the 9/11 attacks by dramatizing both a growth of racism against Arab Americans as well as America’s willingness to rescind personal liberties guaranteed under the Constitution.

Another film that seemed almost designed to inflame prejudices against Middle Easterners and people of Middle Eastern descent was Not Without My Daughter(1991). Based on a true story, the film is about an all-American (that is, white) woman played by Sally Field who marries an Iranian American man and begins a family. He convinces her to make a visit to his homeland, which turns into a permanent stay. In an extreme example of the supposed inability to assimilate, the husband “reverts” to Islamic fundamentalism, much to the shock and fear of his wife. He is willing to let her go, but not his daughter, whom he regards as Iranian and not American. The rest of the film entails the wife’s attempt to escape the country with her daughter. The film and its relevance to Middle Eastern cultures remain hotly debated on fan-based websites: some maintain it is an accurate depiction of how women are treated in some Middle Eastern nations, while others see it as negative stereotyping at its worst.

During the 1990s, growing groups of American citizens such as the ADC (the American-Arab Anti-Discrimination Committee ) began to protest these types of media stereotypes. They picketed films like The Siegeand Rules of Engagement, handing out leaflets challenging the films’ portrayal of Muslim and Arab cultures. An even more vociferous action was waged against the use of stereotypes in Disney’s Aladdin(1992). Disney eventually agreed to rewrite some offensive song lyrics, but not to eliminate or alter other scenes – and the studio has continued to use Arab stereotypes for comic effect in live-action pictures such as Father of the Bride II(1995) and Kazaam(1996). Such protests against media stereotyping have continued into the twenty-first century, but the events of September 11, 2001, seemed to give terrifying credence to the “accuracy” of the terrorist stereotype. Of course, most Muslim and/or Arab Americans have nothing to do with terrorism, yet they have been subjected to increased surveillance, random hate crimes, and continued stereotyping and profiling. Many Americans seemingly make no distinction between Arabs, Arab Americans, and Muslim terrorists. The United States itself was content to invade Iraq in alleged retaliation for the September 11 attacks, despite the fact that Iraq had few-to-no connections with the international terrorists who caused them.

Occasional independent or Hollywood films (such as Party Girl[1995], Sorry, Haters[2005], Crash[2004], or American Dreamz[2006]) may try to individuate Arab Americans, even as the Arab American characters often still fall back into stereotypes. Still, the image of the Arab terrorist continues to be prevalent in American films and television shows. Most recently, and perhaps most egregiously, the “historical” action film 300(2006) cast white British actors as heroic Spartans battling hordes of (literally) monstrous, dark-skinned, and sexually perverse Persians. The film seemed almost designed to exploit and capitalize on current anti-Arab and anti-Muslim feelings in American culture; its grotesque stereotyping encourages audiences to hate and fear its Persian characters while simultaneously inflaming and justifying white masculine violence. However, the film did not go unchallenged by media scholars and even the Iranian government itself.

Against this complex socio-political backdrop, it is perhaps no surprise that Arab and/or Arab American actors in Hollywood have not had an easy time finding challenging or complex characters to play. One of the first actors of openly Arab descent to make a name for himself was Omar Sharif, who was an Egyptian film star before his performance in Lawrence of Arabiaearned him an Oscar nomination and catapulted him to international fame. After his lead role as Dr Zhivago(1965), he played leading men in several Hollywood films including Funny Girl(1968) and Funny Lady(1975). Today he works mostly in Europe. American actors of Lebanese heritage such as Danny Thomas, Jamie Farr, and Casey Kasem have worked more regularly in television and radio. Thomas was the star of the popular sitcom Make Room for Daddy(1953–65), Farr played the cross-dressing Corporal Klinger in the TV show M*A*S*H(1972–83), and Kasem has had a decades-long career as a successful radio host and voice-over artist, performing the voice of Shaggy in the long-running Scooby-Doocartoons.

Shaun Toub as a Persian shopkeeper in Crash(2004), one of the few Hollywood films of recent years to include even one American character of Middle Eastern descent.

Crash, dir. Paul Haggis, copyright © 2004, Lions Gate Films

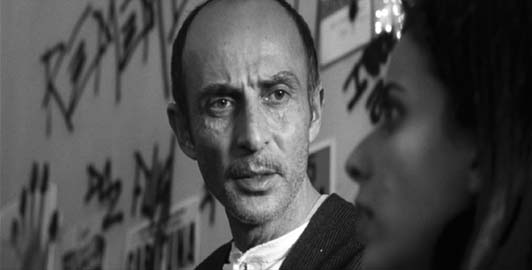

Egyptian-born Omar Sharif, seen here as Jewish entrepreneur Nicky Arnstein opposite Barbra Streisand as Jewish comedienne Fanny Brice in Funny Girl. Who is white and who is not? Funny Girl, copyright © 1968, Columbia

Other actors of Arab descent include F. Murray Abraham (who won an Oscar for his role as Salieri in Amadeus[1984]), Shohreh Aghdashloo (who garnered an Oscar nomination for her role as an Iranian immigrant in House of Sand and Fog[2003]), Alexander Siddig (Dr Bashir on Star Trek: Deep Space Nine[1993–9]), and Tony Shaloub (Monk[2001–]). It should be noted, though, that many actors of Middle Eastern heritage are still regularly cast as terrorists or sheiks; if they want to work, they are sometimes compelled to accept those roles. Also, many still feel compelled to alter or change their Arabic-sounding names in order to work in the business. For example, F. Murray Abraham’s birth name is Fahrid Murray Abraham; the actor’s official stage name potentially hides his Middle Eastern heritage.

Conclusion: Whiteness and American Film Today

Whiteness is still the unspoken ideal in American movies. Yet, as our society continues to become more diverse, so too do our movie screens. During the 1990s, multiculturalism was increasingly endorsed and/or celebrated in America, culminating in the Federal Census Bureau allowing people to check off more than one racial category for the first time in 2000. Possibly in response, many people who regarded themselves as white in the 1990s began reconnecting to their ethnic heritages, taking pride in their Irish, Italian, or other roots. Thus, these individuals could consider themselves bothwhite and part of the nation’s diversity. Also, a number of white-identified youth (predominantly male) increasingly adopted the trappings of African American urban culture (its music, its fashion, its slang) in an effort to distance themselves from whiteness. (Songs like “Pretty Fly for a White Guy” and the film Malibu’s Most Wanted[2003] satirize this trend.)

Furthermore, actors, like all Americans, are coming from increasingly diverse backgrounds, including mixed-race and mixed-nation families. F. Murray Abraham, mentioned above, was born in Pennsylvania to parents of Italian and Syrian descent. Salma Hayek’s heritage is Lebanese and Mexican. Jessica Alba’s father is from Mexico, while her mother is of French and Danish descent. Rashida Jones, who plays Karen Filippelli in the hit comedy The Office(2005–), is the daughter of African American musician Quincy Jones and white actress Peggy Lipton. Other contemporary actors with mixed-ethnic backgrounds include Dwayne “The Rock” Johnson, Jennifer Beals, and Vin Diesel. For a brief moment, Vin Diesel seemed poised to become the next big Hollywood action star, allegedly appealing to black and white audiences simultaneously. Before his Hollywood successes, however, Diesel wrote and directed a short film about media stereotypes. Multi-Facial(1999) follows Diesel’s character as he auditions for roles as an Italian American, a Latino, and a black rapper. His shifting personas in front of the casting directors (as well as his fellow actors) suggest that race and/or ethnicity is merely a matter of performance, a certain attention to and replication of behavioral traits and speech patterns. As a calling card, the film propelled Diesel into his Hollywood career, but it also chides the film industry (and especially casting directors) for perpetuating racial and ethnic stereotypes.

The growth in the number of performers who seem to transcend racial or ethnic categories may seem like a positive development in American film and television. Yet it should be recognized that industry interest in such individuals is often more due to economic interests than social or political ones. If some people regard, for example, Dwayne “The Rock” Johnson as white, and others as a person of color, then he potentially draws in multiple audiences. Furthermore, the public perception of such stars taps into the historically complex issues and opinions over passing and assimilation within white communities andcommunities of color. Still, the growing awareness and acceptance of multi-ethnic identities further complicates what many usually assume as the unproblematic nature of whiteness.

Questions for Discussion

1 Think about your own national, ethnic, or racial heritage. To what extent does it shape your personal identity? Share your thoughts with your classmates. Are people of color more aware of these issues than are many whites? If so, why?

2 What are the pros and cons of assimilation? What should America’s “national identity” be? How does film help to construct that national identity?