THE TEMPEST

The Tempest was almost certainly Shakespeare’s last solo-authored play. We do not know whether he anticipated that this would be the case. It was also the first play to be printed in the First Folio. Again, we do not know whether it was given pride of place because the editors of the Folio regarded it as a showpiece—the summation of the master’s art—or for the more mundane reason that they had a clean copy in the clear hand of the scribe Ralph Crane, which would have given the compositors a relatively easy start as they set to work on the mammoth task of typesetting nearly a million words of Shakespeare. Whether it found its position by chance or design, The Tempest’s place at the end of Shakespeare’s career and the beginning of his collected works has profoundly shaped responses to the play ever since the early nineteenth century. It has come to be regarded as the touchstone of Shakespearean interpretation.

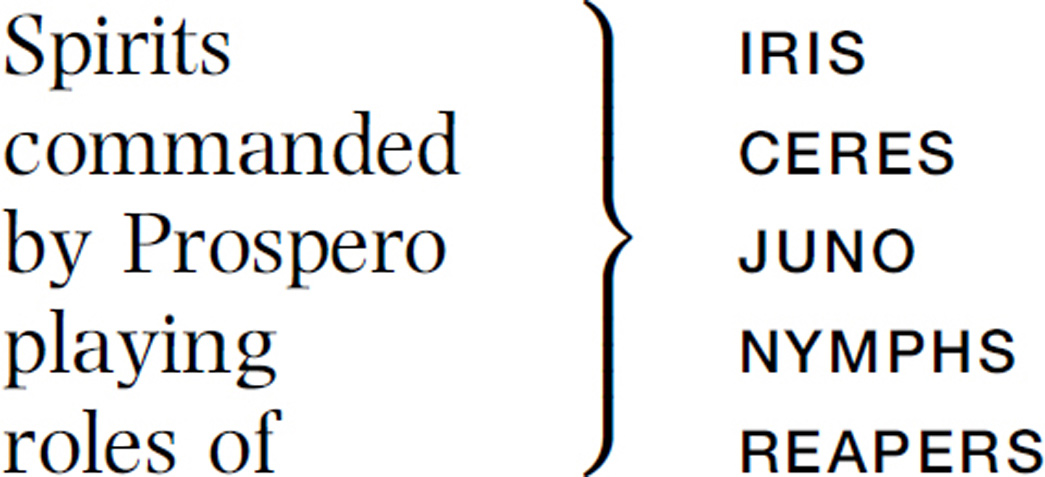

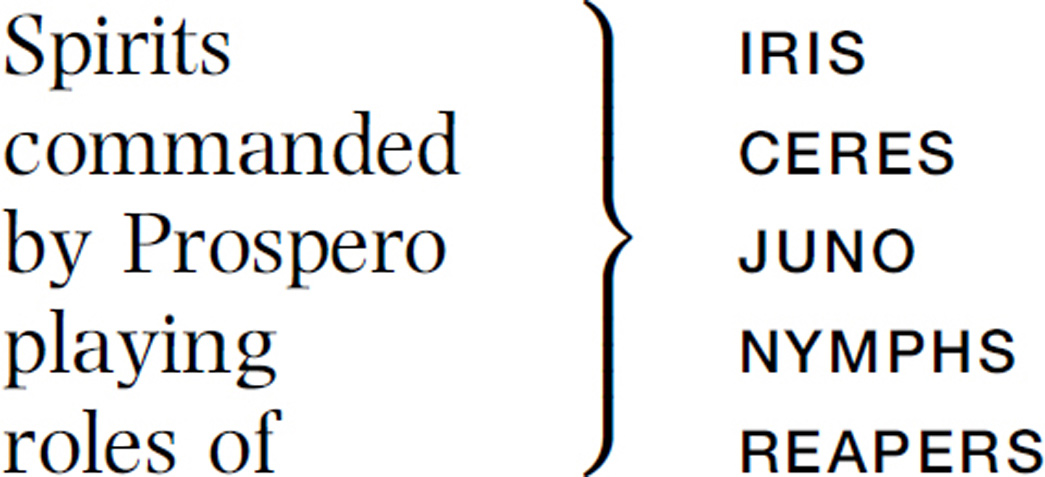

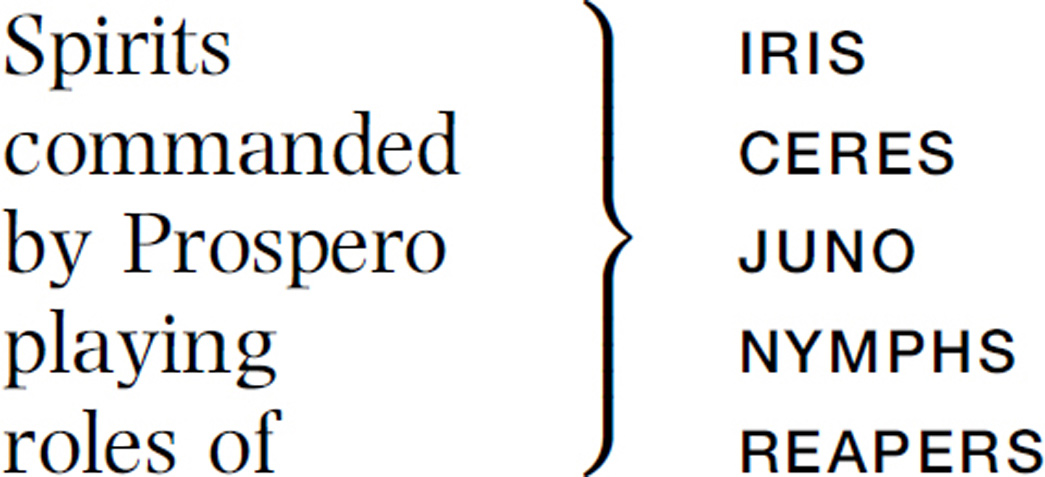

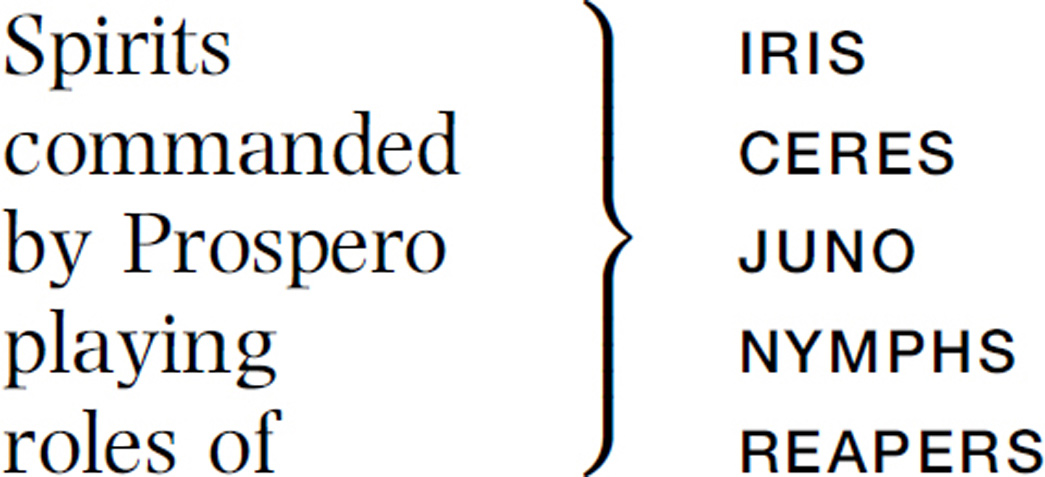

The narrative is concentrated on questions of mastery and rule. During the tempest in the opening scene, the normal social order is out of joint: the boatswain commands the courtiers in the knowledge that the roaring waves care nothing for “the name of king.” Then the back story, unfolded at length in Act 1 scene 2, tells of conspirators who do not respect the title of duke: we learn of Prospero’s loss of power in Milan and the compensatory command he has gained over Ariel and Caliban on the island. The Ferdinand and Miranda love knot is directed toward the future government of Milan and Naples. There is further politic plotting: Sebastian and Antonio’s plan to murder King Alonso and good Gonzalo, the madcap scheme of the base born characters to overthrow Prospero and make drunken butler Stephano king of the island. The theatrical coups performed by Prospero, assisted by Ariel and the other spirits of the island—the freezing of the conspirators, the harpy and the vanishing banquet, the masque of goddesses and agricultural workers, the revelation of the lovers playing at chess—all serve the purpose of requiting the sins of the past, restoring order in the present, and preparing for a harmonious future. Once the work is done, Ariel is released (with a pang) and Prospero is ready to prepare his own spirit for death. Even Caliban will “seek for grace.”

But Shakespeare never keeps it simple. Prospero’s main aim in conjuring up the storm and bringing the court to the island is to force his usurping brother Antonio into repentance. Yet when the climactic confrontation comes, Antonio does not say a word in reply to Prospero’s combination of forgiveness and demand. He wholly fails to follow the good example set by Alonso a few lines before. As for Antonio’s sidekick Sebastian, he has the temerity to ascribe Prospero’s magical foresight to demonic influence. For all the powers at Prospero’s command, there is no way of predicting or controlling human nature. A conscience cannot be created where there is none.

Samuel Taylor Coleridge described Prospero as “the very Shakespeare, as it were, of the tempest.” In other words, the leading character’s conjuring up of the storm in the opening scene corresponds to the dramatist’s conjuring up of the whole world of the play. The art of Prospero harnesses the power of nature in order to bring the other Italian characters to join him in his exile; by the same account, the art of Shakespeare transforms the platform of the stage into a ship at sea and then “an uninhabited island.” “Art” is the play’s key word. Caliban is Prospero’s “other” because he represents the state of nature. In the Darwinian nineteenth century, he was recast as the “missing link” between humankind and our animal ancestors.

Prospero’s backstory tells of a progression from the “liberal arts” that offered a training for governors to the more dangerous “art” of magic. Magical thinking was universal in the age of Shakespeare. Everyone was brought up to believe that there was another realm beyond that of nature, a realm of the spirit and of spirits. “Natural” and “demonic” magic were the two branches of the study and manipulation of preternatural phenomena. Magic meant the knowledge of hidden things and the art of working wonders. For some, it was the highest form of natural philosophy: the word came from magia, the ancient Persian term for wisdom. The “occult philosophy,” as it was known, postulated a hierarchy of powers, with influence descending from disembodied (“intellectual”) angelic spirits to the stellar and planetary world of the heavens to earthly things and their physical changes. The magician ascends to knowledge of higher powers and draws them down artificially to produce wonderful effects. Cornelius Agrippa, author of the influential De occulta philosophia, argued that “ceremonial magic” was needed in order to reach the angelic intelligences above the stars. This was the highest and most dangerous level of activity, since it was all too easy—as Christopher Marlowe’s Dr. Faustus found—to conjure up a devil instead of an angel. The more common form of “natural magic” involved “marrying” heaven to earth, working with the occult correspondences between the stars and the elements of the material world. The enduring conception of astrological influences is a vestige of this mode of thought. For a Renaissance mage such as Girolamo Cardano, who practiced in Milan, medicine, natural philosophy, mathematics, astrology, and dream interpretation were all intimately connected.

But natural magic could never escape its demonic shadow. For every learned mage such as Agrippa or Cardano, there were a thousand village “wise women” practicing folk medicine and fortune-telling. All too often, the latter found themselves demonized as witches, blamed for crop failure, livestock disease, and the other ills of life in the premodern era. Prospero is keen to contrast his own white magic with the black arts of Sycorax, Caliban’s mother, but the play establishes strong parallels between them. He was exiled from Milan to the island because his devotion to his secret studies gave Antonio the opportunity to usurp the dukedom, whilst Sycorax was exiled from Algiers to the island because she was accused of witchcraft; he arrived with his young daughter, whilst she arrived pregnant with the child she had supposedly conceived by sleeping with the devil. Each of them can command the tides and manipulate the spirit world that is embodied by Ariel. When Prospero comes to renounce his magic, he describes his powers in words borrowed from the incantation of another witch, Medea in Ovid’s great storehouse of ancient mythological tales, the Metamorphoses. Prospero at some level registers his own kinship with Sycorax when he says of Caliban “this thing of darkness I / Acknowledge mine.” The splitting of subject and verb across the line ending here, ensuring a moment’s hesitation in the acknowledgment, is an extreme instance of the suppleness with which late Shakespeare handles his iambic pentameter verse.

Shakespeare loved to set up oppositions, then shade his black and white into gray areas of moral complexity. In Milan, Prospero’s inward-looking study of the liberal arts had led to the loss of power and the establishment of tyranny. On the island he seeks to make amends by applying what he has learned, by using active magic to bring repentance, restore his dukedom, and set up a dynastic marriage. Yet at the beginning of the fifth act he sees that to be truly human is a matter not of exercising wisdom for the purposes of rule, but of practicing a more strictly Christian version of virtue. For sixteenth-century humanists, education in princely virtue meant the cultivation for political ends of wisdom, magnanimity, temperance, and integrity. For Prospero what finally matters is kindness. And this is something that the master learns from his pupil: it is Ariel who teaches Prospero about “feeling,” not vice versa.

Ariel represents fire and air, concord and music, loyal service. Caliban is of the earth, associated with discord, drunkenness, and rebellion. Ariel’s medium of expression is delicate verse, whilst Caliban’s is for the most part a robust, often ribald, prose like that of the jester Trinculo and drunken butler Stephano. But, astonishingly, it is Caliban who speaks the play’s most beautiful verse when he hears the music of Ariel. Even in prose, Caliban has a wonderful attunement to the natural environment: he knows every corner, every species of the island. Prospero calls him “A devil, a born devil, on whose nature / Nurture can never stick,” yet in the very next speech Caliban enters with the line “Pray you tread softly, that the blind mole may not hear a footfall,” words of such strong imagination that Prospero’s claim is instantly belied.

Caliban’s purported sexual assault on Miranda shows that Prospero failed in his attempt to tame the animal instincts of the “man-monster” and educate him into humanity. But who bears responsibility for the failure? Could it be that the problem arises from what Prospero has imprinted on Caliban’s memory, not from the latter’s nature? Caliban initially welcomed Prospero to the island and offered to share its fruits, every bit in the manner of the “noble savages” in Michel de Montaigne’s essay “Of the Cannibals,” which was another source from which Shakespeare quoted in the play (Gonzalo’s Utopian “golden age” vision of how he would govern the isle is borrowed from the English translation of Montaigne). Caliban only acts basely after Prospero has printed that baseness on him; what makes Caliban “filth” may be the lessons in which Prospero has taught him that he is “filth.”

Caliban understands the power of the book: as fashioners of modern coups d’état begin by seizing the television station, so he stresses that the rebellion against Prospero must begin by taking possession of his books. But Stephano has another book. “Here is that which will give language to you,” he says to Caliban, replicating Prospero’s gaining of control through language—but in a different mode. Textual inculcation is replaced by intoxication: the book that is kissed is the bottle. The dialogic spirit that is fostered by Shakespeare’s technique of scenic counterpoint thus calls into question Prospero’s use of books. If Stephano and Trinculo achieve through their alcohol what Prospero achieves through his teaching (in each case Caliban is persuaded to serve and to share the fruits of the isle), is not that teaching exposed as potentially nothing more than a means of social control? Prospero often seems more interested in the power structure that is established by his schoolmastering than in the substance of what he teaches. It is hard to see how making Ferdinand carry logs is intended to inculcate virtue; its purpose is to elicit submission.

Arrival on an island uninhabited by Europeans, talk of “plantation,” an encounter with a “savage” in which alcohol is exchanged for survival skills, a process of language learning in which it is made clear who is master and who is slave, fear that the slave will impregnate the master’s daughter, the desire to make the savage seek for Christian “grace” (though also a proposal that he should be shipped to England and exhibited for profit), references to the dangerous weather of the Bermudas and to a “brave new world”: in all these respects, The Tempest conjures up the spirit of European colonialism. Shakespeare had contacts with members of the Virginia Company, which had been established by royal charter in 1606 and was instrumental in the foundation of the Jamestown colony in America the following year. Some time in the autumn of 1610, a letter reached England describing how a fleet sent to reinforce the colony had been broken up by a storm in the Caribbean; the ship carrying the new governor had been driven to Bermuda, where the crew and passengers had wintered. Though the letter was not published at the time, it circulated in manuscript and inspired at least two pamphlets about these events. Scholars debate the extent to which Shakespeare made direct use of these materials, but certain details of the storm and the island seem to be derived from them. There is no doubt that the seemingly miraculous survival of the governor’s party and the fertile environment they discovered in the Bahamas were topics of great public interest at the time of the play.

The British Empire, the slave trade, and the riches of the spice routes lay in the future. Shakespeare’s play is set in the Mediterranean, not the Caribbean. Caliban cannot strictly be described as a native of the island. And yet the play intuits the dynamic of colonial possession and dispossession with such uncanny power that in 1950 a book by Octave Mannoni called The Psychology of Colonisation could argue that the process functioned by means of a pair of reciprocal neuroses: the “Prospero complex” on the part of the colonizer and the “Caliban complex” on that of the colonized. It was in response to Mannoni that Frantz Fanon wrote Black Skin, White Masks, a book that did much to shape the intellectual terrain of the “postcolonial” era. For many Anglophone Caribbean writers of the late twentieth century, The Tempest, and the figure of Caliban in particular, became a focal point for discovery of their own literary voices. The play is less a reflection of imperial history—after all, Prospero is an exile, not a venturer—than an anticipation of it.

As regular players at royal command performances in the Whitehall Palace, the King’s Men knew that from the end of 1608 onward, the teenage Princess Elizabeth was resident at court. A cultured young woman who enjoyed music and dancing, she participated in court festivals and in 1610 danced in a masque called Tethys. Masques—performed by a mixed cast of royalty, courtiers, and professional actors, staged with spectacular scenery and elaborate music—were the height of fashion at court in these years. Shakespeare’s friend and rival Ben Jonson, working in conjunction with the designer Inigo Jones, was carving out a role for himself as the age’s leading masque-wright. In 1608 he introduced the “antimasque” (or “antemasque”), a convention whereby grotesque figures known as “antics” danced boisterously prior to the graceful and harmonious masque itself. Shakespeare nods to contemporary fashion by including a betrothal masque within the action of The Tempest, together with the antimasque farce of Caliban, Stephano, and Trinculo smelling of horse-piss, stealing clothes from a line, and being chased away by dogs. One almost wonders whether the figure of Prospero is a gentle parody of Ben Jonson: his theatrical imagination is bound by the classical unities of time and place (as Jonson’s was) and he stages a court masque (as Jonson did). Perhaps this is why a few years later, in his Bartholomew Fair, Jonson parodied The Tempest in return.

Prospero’s Christian language reaches its most sustained pitch in the epilogue, but his final request is for the indulgence not of God but of the audience. At the last moment, humanist learning is replaced not by Christian but by theatrical faith. Because of this it has been possible for the play to be read, as it so often has been since the Romantic period, as Shakespeare’s defense of his own dramatic art. Ironically, though, the play itself is profoundly skeptical of the power of the book and even of the theater. The book of art is drowned, whilst the masque and its players dissolve into vacancy like a “baseless fabric” or a dream.

KEY FACTS

PLOT: Twelve years ago Prospero, the Duke of Milan, was usurped by his brother, Antonio, with the help of Alonso, King of Naples, and the King’s brother Sebastian. Prospero and his baby daughter Miranda were put to sea and landed on a distant island where ever since, by the use of his magic art, he has ruled over the spirit Ariel and the savage Caliban. He uses his powers to raise a storm that shipwrecks his enemies on the island. Alonso searches for his son, Ferdinand, although fearing him to be drowned. Sebastian plots to kill Alonso and seize the crown. The drunken butler, Stephano, and the jester, Trinculo, encounter Caliban and are persuaded by him to kill Prospero so that they can rule the island. Ferdinand meets Miranda and they fall instantly in love. Prospero sets heavy tasks to test Ferdinand and, when satisfied, presents the young couple with a betrothal masque. As Prospero’s plan draws to its climax, he confronts his enemies and forgives them. Prospero grants Ariel his freedom and prepares to leave the island for Milan.

MAJOR PARTS: (with percentage of lines/number of speeches/scenes on stage) Prospero (30%/115/5), Ariel (9%/45/6), Caliban (8%/50/5), Stephano (7%/60/4), Gonzalo (7%/52/4), Sebastian (5%/67/4), Antonio (6%/57/4), Miranda (6%/49/4), Ferdinand (6%/31/4), Alonso (5%/40/4), Trinculo (4%/39/4).

LINGUISTIC MEDIUM: 80% verse, 20% prose.

DATE: 1611. Performed at court, November 1, 1611; uses source material not available before autumn 1610.

SOURCES: No known source for main plot, but some details of the tempest and the island seem to derive from William Strachey, A True Reportory of the Wreck and Redemption of Sir Thomas Gates, Knight (written 1610, published in Purchas his Pilgrims, 1625) and perhaps Sylvester Jourdain, A Discovery of the Bermudas (1610) and the Virginia Company’s pamphlet A True Declaration of the Estate of the Colony in Virginia (1610); several allusions to Virgil’s Aeneid and Ovid’s Metamorphoses (most notably the imitation in Act 5 scene 1 of Arthur Golding’s 1567 translation of Medea’s incantation in Ovid’s 7th book); Gonzalo’s “golden age” oration in Act 2 scene 1 based closely on Michel de Montaigne’s essay “Of the Cannibals,” translated by John Florio (1603).

TEXT: First Folio of 1623 is the only early printed text. Based on a transcript by Ralph Crane, professional scribe working for the King’s Men. Generally good quality of printing.

PROSPERO, the right Duke of Milan

MIRANDA, his daughter

ALONSO, King of Naples

SEBASTIAN, his brother

ANTONIO, Prospero’s brother, the usurping Duke of Milan

FERDINAND, son to the King of Naples

GONZALO, an honest old councillor

ADRIAN and FRANCISCO, lords

TRINCULO, a jester

STEPHANO, a drunken butler

MASTER of a ship

BOATSWAIN

MARINERS

CALIBAN, a savage and deformed slave

ARIEL, an airy spirit

The Scene: an uninhabited island

running scene 1

A tempestuous noise of thunder and lightning heard. Enter a Shipmaster and a Boatswain

BOATSWAIN

BOATSWAIN Here, master. What cheer?

2

MASTER

MASTER Good:

3 speak to th’mariners. Fall to’t yarely, or we run ourselves aground! Bestir,

4 bestir!

Exit

Enter Mariners

BOATSWAIN

BOATSWAIN Heigh, my hearts!

5 Cheerly, cheerly, my hearts! Yare, yare! Take in the topsail. Tend

6 to th’master’s whistle.—

To the storm Blow, till thou burst thy wind, if room enough.

Enter Alonso, Sebastian, Antonio, Ferdinand, Gonzalo and others

ALONSO

ALONSO Good boatswain, have

8 care. Where’s the master? Play the men.

BOATSWAIN

BOATSWAIN I pray now, keep below.

ANTONIO

ANTONIO Where is the master, boatswain?

BOATSWAIN

BOATSWAIN Do you not hear him? You mar

11 our labour. Keep your cabins! You do assist the storm.

GONZALO

GONZALO Nay, good, be patient.

BOATSWAIN

BOATSWAIN When the sea is. Hence!

14 What cares these roarers for the name of king? To cabin! Silence! Trouble us not.

GONZALO

GONZALO Good, yet remember whom thou hast aboard.

BOATSWAIN

BOATSWAIN None that I more love than myself. You are a counsellor:

17 if you can command these elements to silence, and work

18 the peace of the present, we will not hand

19 a rope more: use your authority. If you cannot, give thanks you have lived so long, and make yourself ready in your cabin for the mischance of the hour, if it so hap.

21—

To the Mariners Cheerly, good hearts!—

To the Courtiers

Out of our way, I say.

Exeunt [Boatswain with Mariners, followed by Alonso, Sebastian, Antonio, and Ferdinand]

GONZALO

GONZALO I have great comfort from this fellow: methinks he

23 hath no drowning mark

24 upon him: his complexion is perfect gallows. Stand fast, good Fate, to his

hanging: make the rope of his destiny

25 our cable, for our own doth little advantage. If he be not born to be hanged, our case is miserable.

Exit

Enter Boatswain

BOATSWAIN

BOATSWAIN Down

27 with the topmast! Yare! Lower, lower! Bring her to try with main course. (

A cry within) A plague upon this howling! They are louder than the weather or our office.

29

Enter Sebastian, Antonio and Gonzalo

Yet again? What do you here? Shall we give o’er30 and drown? Have you a mind to sink?

SEBASTIAN

SEBASTIAN A pox

32 o’your throat, you bawling, blasphemous, incharitable dog!

BOATSWAIN

BOATSWAIN Work you then.

ANTONIO

ANTONIO Hang, cur!

34 Hang, you whoreson, insolent noisemaker! We are less afraid to be drowned than thou art.

GONZALO

GONZALO I’ll warrant

36 him for drowning, though the ship were no stronger than a nutshell and as leaky as an unstanched

37 wench.

BOATSWAIN

BOATSWAIN Lay her ahold,

38 ahold! Set her two courses off to sea again! Lay her off!

Enter Mariners, wet

MARINERS

MARINERS All lost! To prayers, to prayers! All lost!

BOATSWAIN

BOATSWAIN What, must

40 our mouths be cold?

GONZALO

GONZALO The king and prince at prayers: let’s assist them, for our case is as theirs.

SEBASTIAN

SEBASTIAN I’m out of patience.

ANTONIO

ANTONIO We are merely

43 cheated of our lives by drunkards. This wide-chopped rascal: would thou mightst lie drowning, the washing of ten tides!

44

45

45 GONZALO

GONZALO He’ll be hanged yet,

45

Though every drop of water swear against it

And gape at wid’st47 to glut him.

[Exeunt Boatswain and Mariners]

A confused noise within

[VOICES OFF-STAGE]

[VOICES OFF-STAGE] Mercy on us! — We split,

48 we split! — Farewell, my wife and children! — Farewell, brother! — We split, we split, we split!

ANTONIO

ANTONIO Let’s all sink wi’th’king.

SEBASTIAN

SEBASTIAN Let’s take leave of him.

Exeunt [Antonio and Sebastian]

GONZALO

GONZALO Now would I give a thousand furlongs

52 of sea for an acre of barren ground: long heath,

53 brown furze, anything. The wills above be done! But I would fain

54 die a dry death.

Exit

running scene 2

Enter Prospero and Miranda

MIRANDA

MIRANDA If by your art,

1 my dearest father, you have

Put the wild waters in this roar, allay2 them.

The sky, it seems, would pour down stinking pitch,3

But that the sea, mounting to th’welkin’s4 cheek,

5

5 Dashes the fire5 out. O, I have suffered

With those that I saw suffer: a brave6 vessel —

Who had, no doubt, some noble creature in her —

Dashed all to pieces. O, the cry did knock

Against my very heart. Poor souls, they perished.

10

10 Had I been any god of power, I would

Have sunk the sea within the earth, or ere11

It should the good ship so have swallowed, and

The fraughting souls13 within her.

PROSPERO

PROSPERO Be collected:

14

15

15 No more amazement.15 Tell your piteous heart

There’s no harm done.

MIRANDA

MIRANDA O, woe the day!

PROSPERO

PROSPERO No harm:

I have done nothing but in care of thee —

20

20 Of thee, my dear one, thee, my daughter — who

Art ignorant of what thou art: nought knowing

Of whence I am,22 nor that I am more better

Than Prospero, master of a full poor cell,23

And thy no greater father.24

25

25 MIRANDA

MIRANDA More to know

25

Did never meddle with26 my thoughts.

PROSPERO

PROSPERO ’Tis time

I should inform thee further. Lend thy hand

And pluck my magic garment from me. So: Lays down his magic cloak

30

30 Lie there, my art. Wipe thou thine eyes, have comfort.

The direful spectacle of the wreck, which touched

The very virtue of compassion in thee,

I have with such provision33 in mine art

So safely ordered that there is no soul —

35

35 No, not so much perdition35 as an hair

Betid36 to any creature in the vessel

Which thou heard’st cry, which thou saw’st sink. Sit down, Miranda sits

For thou must now know further.

MIRANDA

MIRANDA You have often

40

40 Begun to tell me what I am, but stopped

And left me to a bootless inquisition,41

Concluding ‘Stay: not yet.’

PROSPERO

PROSPERO The hour’s now come,

The very minute bids thee ope44 thine ear:

45

45 Obey, and be attentive. Canst thou remember

A time before we came unto this cell?

I do not think thou canst, for then thou wast not

Out48 three years old.

MIRANDA

MIRANDA Certainly, sir, I can.

50

50 PROSPERO

PROSPERO By what? By any other house or person?

Of any thing the image, tell me, that

Hath52 kept with thy remembrance.

MIRANDA

MIRANDA ’Tis far off,

And rather like a dream than an assurance54

55

55 That my remembrance warrants.55 Had I not

Four or five women once that tended56 me?

PROSPERO

PROSPERO Thou hadst; and more, Miranda. But how is it

That this lives in thy mind? What see’st thou else

In the dark backward59 and abysm of time?

60

60 If thou rememb’rest aught60 ere thou cam’st here,

How thou cam’st here thou mayst.

MIRANDA

MIRANDA But that I do not.

PROSPERO

PROSPERO Twelve year since, Miranda, twelve year since,

Thy father was the Duke of Milan and

65

65 A prince of power.

MIRANDA

MIRANDA Sir, are not you my father?

PROSPERO

PROSPERO Thy mother was a piece

67 of virtue, and

She said thou wast my daughter; and thy father

Was Duke of Milan, and his only heir

70

70 And princess, no worse issued.70

MIRANDA

MIRANDA O the heavens!

What foul play had we, that we came from thence?

Or blessèd73 wast we did?

PROSPERO

PROSPERO Both, both, my girl.

75

75 By foul play — as thou say’st — were we heaved thence,

But blessedly holp76 hither.

MIRANDA

MIRANDA O, my heart bleeds

To think o’th’teen78 that I have turned you to,

Which is from79 my remembrance. Please you, further.

80

80 PROSPERO

PROSPERO My brother and thy uncle, called Antonio —

I pray thee, mark81 me — that a brother should

Be so perfidious82 — he whom next thyself

Of all the world I loved, and to him put

The manage84 of my state, as at that time

85

85 Through all the signories85 it was the first,

And Prospero the prime86 duke, being so reputed

In dignity, and for the liberal arts87

Without a parallel; those being all my study,

The government I cast upon my brother

90

90 And to my state90 grew stranger, being transported

And rapt in secret studies. Thy false uncle —

Dost thou attend me?

MIRANDA

MIRANDA Sir, most heedfully.

PROSPERO

PROSPERO Being once perfected

94 how to grant suits,

95

95 How to deny them, who t’advance and who

To trash for over-topping,96 new created

The creatures that were mine, I say, or changed ’em,97

Or else new formed98 ’em; having both the key

Of officer and office, set all hearts i’th’state

100

100 To what tune pleased his ear, that100 now he was

The ivy101 which had hid my princely trunk

And sucked my verdure102 out on’t.— Thou attend’st not.

MIRANDA

MIRANDA O good sir, I do.

PROSPERO

PROSPERO I pray thee, mark me:

105

105 I, thus neglecting worldly ends,105 all dedicated

To closeness106 and the bettering of my mind

With that, which but107 by being so retired,

O’er-prized108 all popular rate, in my false brother

Awaked an evil nature, and my trust,

110

110 Like a good parent,110 did beget of him

A falsehood111 in its contrary, as great

As my trust was, which had indeed no limit,

A confidence sans113 bound. He being thus lorded,

Not only with what my revenue yielded,

115

115 But what my power might else exact:115 like one

Who having into116 truth, by telling of it,

Made such a sinner of his memory

To credit his own lie, he did believe

He was indeed the duke, out o’th’substitution119

120

120 And executing th’outward face120 of royalty

With all prerogative: hence his ambition growing —

Dost thou hear?

MIRANDA

MIRANDA Your tale, sir, would cure deafness.

PROSPERO

PROSPERO To have no screen

124 between this part he played,

125

125 And him125 he played it for, he needs will be

Absolute Milan.126 Me — poor man — my library

Was dukedom large enough: of temporal royalties127

He thinks me now incapable. Confederates128 —

So dry129 he was for sway — wi’th’King of Naples

130

130 To give him annual tribute,130 do him homage,

Subject131 his coronet to his crown, and bend

The dukedom yet132 unbowed — alas, poor Milan —

To most ignoble stooping.

MIRANDA

MIRANDA O the heavens!

135

135 PROSPERO

PROSPERO Mark his condition

135 and th’event, then tell me

If136 this might be a brother.

MIRANDA

MIRANDA I should sin

To think but138 nobly of my grandmother:

Good wombs have borne bad sons.

140

140 PROSPERO

PROSPERO Now the condition.

This King of Naples, being an enemy

To me inveterate,142 hearkens my brother’s suit,

Which was, that he,143 in lieu o’th’premises

Of homage, and I know not how much tribute,144

145

145 Should presently extirpate145 me and mine

Out of the dukedom, and confer fair Milan,

With all the honours, on my brother: whereon,

A treacherous army levied, one midnight

Fated to th’purpose, did Antonio open

150

150 The gates of Milan, and i’th’dead of darkness

The ministers151 for th’purpose hurried thence

Me and thy crying self.

MIRANDA

MIRANDA Alack, for pity!

I, not rememb’ring how I cried out then,

155

155 Will cry it o’er again: it is a hint155

That wrings mine eyes to’t.

PROSPERO

PROSPERO Hear a little further,

And then I’ll bring thee to the present business

Which now’s upon’s: without the which, this story

160

160 Were most impertinent.160

MIRANDA

MIRANDA Wherefore did they not

That hour destroy us?

PROSPERO

PROSPERO Well demanded, wench:

My tale provokes that question. Dear, they durst164 not,

165

165 So dear the love my people bore me: nor set

A mark so bloody on the business: but

With colours fairer, painted167 their foul ends.

In few,168 they hurried us aboard a barque,

Bore us some leagues to sea, where they prepared

170

170 A rotten carcass of a butt,170 not rigged,

Nor tackle, sail, nor mast: the very rats

Instinctively have quit it. There they hoist172 us,

To cry to th’sea that roared to us; to sigh

To th’winds, whose pity sighing back again,

175

175 Did us but loving wrong.175

MIRANDA

MIRANDA Alack, what trouble

Was I then to you!

PROSPERO

PROSPERO O, a cherubin

178

Thou wast that did preserve me. Thou didst smile,

180

180 Infused with a fortitude from heaven,

When I have decked181 the sea with drops full salt,

Under my burden groaned, which182 raised in me

An undergoing stomach,183 to bear up

Against what should ensue.

185

185 MIRANDA

MIRANDA How came we ashore?

Prospero sits

PROSPERO

PROSPERO By providence divine.

Some food we had, and some fresh water, that

A noble Neapolitan, Gonzalo,

Out of his charity — who being then appointed

190

190 Master of this design190 — did give us, with

Rich garments, linens, stuffs191 and necessaries,

Which since have steaded much.192 So, of his gentleness,

Knowing I loved my books, he furnished me

From mine own library with volumes that

195

195 I prize above my dukedom.

MIRANDA

MIRANDA Would

196 I might

But ever see that man.

PROSPERO

PROSPERO Now I arise:

Prospero stands

Sit still,199 and hear the last of our sea-sorrow.

200

200 Here in this island we arrived, and here

Have I, thy schoolmaster, made thee more profit201

Than other princes can that have more time

For vainer203 hours, and tutors not so careful.

MIRANDA

MIRANDA Heavens thank you for’t. And now, I pray you, sir,

205

205 For still ’tis beating in my mind: your reason

For raising this sea-storm?

PROSPERO

PROSPERO Know thus far forth:

By accident most strange, bountiful Fortune —

Now my dear lady209 — hath mine enemies

210

210 Brought to this shore: and by my prescience210

I find my zenith211 doth depend upon

A most auspicious star, whose influence212

If now I court not, but omit,213 my fortunes

Will ever after droop. Here cease more questions:

215

215 Thou art inclined to sleep. ’Tis a good dullness,215

And give it way:216 I know thou canst not choose.— Miranda sleeps

Come away, servant, come. I am ready now.

Approach, my Ariel,218 come.

Enter Ariel

ARIEL

ARIEL All hail, great master! Grave

219 sir, hail! I come

220

220 To answer thy best pleasure; be’t to fly,

To swim, to dive into the fire, to ride

On the curled clouds: to thy strong bidding task222

Ariel and all his quality.223

PROSPERO

PROSPERO Hast thou, spirit,

225

225 Performed to point225 the tempest that I bade thee?

ARIEL

ARIEL To every article.

I boarded the king’s ship: now on the beak,227

Now in the waist,228 the deck, in every cabin,

I flamed amazement:229 sometime I’d divide

230

230 And burn in many places; on the topmast,

The yards231 and bowsprit would I flame distinctly,

Then meet and join. Jove’s232 lightning, the precursors

O’th’dreadful thunderclaps, more momentary

And sight-outrunning234 were not; the fire and cracks

235

235 Of sulphurous roaring, the most mighty Neptune235

Seem to besiege and make his bold waves tremble,

Yea, his dread trident237 shake.

PROSPERO

PROSPERO My brave spirit!

Who was so firm, so constant, that this coil239

240

240 Would not infect his reason?

But felt a fever of the mad242 and played

Some tricks of desperation. All but mariners

Plunged in the foaming brine and quit the vessel,

245

245 Then all afire245 with me: the king’s son, Ferdinand,

With hair up-staring246 — then like reeds, not hair —

Was the first man that leaped; cried ‘Hell is empty

And all the devils are here.’

PROSPERO

PROSPERO Why, that’s my spirit!

250

250 But was not this nigh250 shore?

ARIEL

ARIEL Close by, my master.

PROSPERO

PROSPERO But are they, Ariel, safe?

ARIEL

ARIEL Not a hair perished:

On their sustaining254 garments not a blemish,

255

255 But fresher than before: and, as thou bad’st me,

In troops256 I have dispersed them ’bout the isle.

The king’s son have I landed by himself,

Whom I left cooling of258 the air with sighs

In an odd angle259 of the isle, and sitting,

260

260 His arms in this sad knot.260 Folds his arms

PROSPERO

PROSPERO Of the king’s ship,

The mariners, say how thou hast disposed,

And all the rest o’th’fleet?

ARIEL

ARIEL Safely in harbour

265

265 Is the king’s ship: in the deep nook where once

Thou call’dst me up at midnight to fetch dew266

From the still-vexed Bermudas,267 there she’s hid;

The mariners all under hatches268 stowed,

Who, with a charm269 joined to their suffered labour,

270

270 I have left asleep: and for the rest o’th’fleet —

Which I dispersed — they all have met again,

And are upon the Mediterranean float272

Bound sadly home for Naples,

Supposing that they saw the king’s ship wrecked

275

275 And his great person perish.

PROSPERO

PROSPERO Ariel, thy charge

Exactly is performed; but there’s more work:

What is the time o’th’day?

ARIEL

ARIEL Past the mid season.

279

280

280 PROSPERO

PROSPERO At least two glasses.

280 The time ’twixt six and now

Must by us both be spent most preciously.281

ARIEL

ARIEL Is there more toil? Since thou dost give me pains,

282

Let me remember283 thee what thou hast promised,

Which is not yet performed me.

285

285 PROSPERO

PROSPERO How now? Moody?

285

What is’t thou canst demand?

PROSPERO

PROSPERO Before the time be out?

288 No more!

290

290 Remember I have done thee worthy service,

Told thee no lies, made thee no mistakings, served

Without or292 grudge or grumblings: thou did promise

To bate293 me a full year.

PROSPERO

PROSPERO Dost thou forget

295

295 From what a torment I did free thee?

PROSPERO

PROSPERO Thou dost: and think’st it much to tread

297 the ooze

Of the salt deep,

To run upon the sharp wind of the north,

300

300 To do me business in the veins o’th’earth

When it is baked with frost.

ARIEL

ARIEL I do not, sir.

PROSPERO

PROSPERO Thou liest, malignant thing. Hast thou forgot

The foul witch Sycorax,304 who with age and envy

305

305 Was grown into a hoop?305 Hast thou forgot her?

PROSPERO

PROSPERO Thou hast. Where was she born? Speak: tell me.

ARIEL

ARIEL Sir, in Algiers.

308

PROSPERO

PROSPERO O, was she so? I must

310

310 Once in a month recount what thou hast been,

Which thou forget’st. This damned witch Sycorax,

For mischiefs manifold, and sorceries terrible

To enter human hearing, from Algiers,

Thou know’st, was banished: for314 one thing she did

315

315 They would not take her life. Is not this true?

PROSPERO

PROSPERO This blue-eyed

317 hag was hither brought with child,

And here was left by th’sailors. Thou, my slave,

As thou report’st thyself, was then her servant:

320

320 And, for320 thou wast a spirit too delicate

To act her earthy321 and abhorred commands,

Refusing her grand hests,322 she did confine thee

By help of her more potent ministers,323

And in her most unmitigable324 rage,

325

325 Into a cloven325 pine, within which rift

Imprisoned thou didst painfully remain

A dozen years: within which space she died,

And left thee there, where thou didst vent thy groans

As329 fast as mill-wheels strike. Then was this island —

330

330 Save for the son that she did litter330 here,

A freckled whelp,331 hag-born — not honoured with

A human shape.

ARIEL

ARIEL Yes: Caliban

333 her son.

PROSPERO

PROSPERO Dull thing,

334 I say so: he, that Caliban

335

335 Whom now I keep in service.335 Thou best know’st

What torment I did find thee in: thy groans

Did make wolves337 howl and penetrate the breasts

Of ever-angry bears; it was a torment

To lay upon the damned, which Sycorax

340

340 Could not again undo. It was mine art,

When I arrived and heard thee, that made gape341

The pine and let thee out.

ARIEL

ARIEL I thank thee, master.

PROSPERO

PROSPERO If thou more murmur’st,

344 I will rend an oak

345

345 And peg345 thee in his knotty entrails till

Thou hast howled away twelve winters.

ARIEL

ARIEL Pardon, master:

I will be correspondent348 to command

And do my spriting349 gently.

350

350 PROSPERO

PROSPERO Do so: and after two days

I will discharge351 thee.

ARIEL

ARIEL That’s my noble master!

What shall I do? Say what? What shall I do?

PROSPERO

PROSPERO Go make thyself like a nymph o’th’sea,

355

355 Be subject to no sight but thine and mine: invisible

To every eyeball else. Go take this shape

And hither come in’t: go! Hence with diligence!

Exit [Ariel]

Awake, dear heart, awake. Thou hast slept well. Awake. To Miranda

MIRANDA

MIRANDA The strangeness of your story put

360

360 Heaviness360 in me.

PROSPERO

PROSPERO Shake it off. Come on:

We’ll visit Caliban, my slave, who never

Yields us kind answer.

MIRANDA

MIRANDA ’Tis a villain,

364 sir, I do not love to look on.

365

365 PROSPERO

PROSPERO But, as ’tis,

We cannot miss366 him: he does make our fire,

Fetch in our wood and serves in offices367

That profit us. What, ho! Slave! Caliban!

Thou earth,369 thou! Speak!

370

370 CALIBAN

CALIBAN There’s wood enough within.

Within

PROSPERO

PROSPERO Come forth, I say! There’s other business for thee:

Come, thou tortoise! When?

Enter Ariel like a water-nymph

Fine apparition: my quaint373 Ariel,

Hark in thine ear.

375

375 ARIEL

ARIEL My lord, it shall be done.

Exit

PROSPERO

PROSPERO Thou poisonous slave, got

376 by the devil himself

Upon thy wicked dam:377 come forth!

Enter Caliban

CALIBAN

CALIBAN As wicked dew as e’er my mother brushed

With raven’s feather from unwholesome fen379

380

380 Drop on you both! A southwest380 blow on ye

And blister you all o’er!

PROSPERO

PROSPERO For this, be sure, tonight thou shalt have cramps,

Side-stitches that shall pen thy breath up: urchins383

Shall, for that vast384 of night that they may work,

385

385 All exercise385 on thee: thou shalt be pinched

As386 thick as honeycomb, each pinch more stinging

Than387 bees that made ’em.

CALIBAN

CALIBAN I must eat my dinner.

This island’s mine by Sycorax my mother,

390

390 Which thou tak’st from me. When thou cam’st first,

Thou strok’st me and made much of me: wouldst give me

Water with berries392 in’t, and teach me how

To name the bigger393 light, and how the less,

That burn by day and night: and then I loved thee

395

395 And showed thee all the qualities o’th’isle,

The fresh springs, brine-pits,396 barren place and fertile.

Cursed be I that did so! All the charms397

Of Sycorax — toads, beetles, bats — light398 on you!

For I am all the subjects that you have,

400

400 Which first was mine own king: and here you sty400 me

In this hard rock,401 whiles you do keep from me

The rest o’th’island.

PROSPERO

PROSPERO Thou most lying slave,

Whom stripes404 may move, not kindness! I have used thee —

405

405 Filth as thou art — with humane405 care, and lodged thee

In mine own cell, till thou didst seek to violate406

The honour of my child.

CALIBAN

CALIBAN O

ho, O ho! Would’t had been done!

Thou didst prevent me: I409 had peopled else

410

410 This isle with Calibans.

MIRANDA

MIRANDA Abhorred slave,

Which any print412 of goodness wilt not take,

Being capable413 of all ill. I pitied thee,

Took pains to make thee speak, taught thee each hour

415

415 One thing or other: when thou didst not, savage,

Know thine own meaning, but wouldst gabble like

A thing most brutish, I endowed thy purposes

With words that made them known. But thy vile race418 —

Though thou didst learn — had that in’t which good natures

420

420 Could not abide to be with: therefore wast thou

Deservedly confined into this rock, who hadst

Deserved more422 than a prison.

CALIBAN

CALIBAN You taught me language, and my profit on’t

Is, I know how to curse. The red-plague424 rid you

425

425 For learning425 me your language.

PROSPERO

PROSPERO Hag-seed,

426 hence!

Fetch us in fuel, and be quick: thou’rt best427

To answer other business. Shrug’st thou, malice?

If thou neglect’st or dost unwillingly

430

430 What I command, I’ll rack430 thee with old cramps,

Fill all thy bones with aches, make thee roar,

That beasts shall tremble at thy din.

CALIBAN

CALIBAN No, pray thee.—

I must obey: his art is of such power, Aside

435

435 It would control my dam’s god, Setebos,435

And make a vassal436 of him.

PROSPERO

PROSPERO So, slave, hence!

Exit Caliban

Enter Ferdinand, and Ariel, invisible, playing and singing

ARIEL

ARIEL Come unto these yellow sands,

Song

And then take hands:

440

440 Curtsied when you have, and kissed

The wild waves whist:441

Foot it featly442 here and there,

And, sweet sprites, bear

The burden.

445

445 [SPIRITS

[SPIRITS Within,

sing the] (

burden,

445 dispersedly)

Hark, hark! Bow-wow!

The watch-dogs bark: bow-wow.

ARIEL

ARIEL Hark, hark! I hear

The strain449 of strutting chanticleer

450

450 Cry, cock-a-diddle-dow.

FERDINAND

FERDINAND Where should this music be? I’th’air or th’earth?

It sounds no more: and sure it waits upon452

Some god o’th’island. Sitting on a bank,

Weeping again the454 king my father’s wreck,

455

455 This music crept by me upon the waters,

Allaying both their fury and my passion456

With its sweet air: thence I have followed it —

Or it hath drawn me rather — but ’tis gone.

No, it begins again.

460

460 ARIEL

ARIEL Full fathom five

460 thy father lies,

Song

Of his bones are coral made:

Those are pearls that were his eyes:

Nothing of him that doth fade,463

But doth suffer464 a sea-change

465

465 Into something rich and strange.

Sea-nymphs hourly ring his knell:466

445 [SPIRITS

[SPIRITS Within,

sing the] (

burden) Ding-dong.

ARIEL

ARIEL Hark! Now I hear them: ding-dong, bell.

FERDINAND

FERDINAND The ditty

469 does remember my drowned father.

470

470 This is no mortal470 business, nor no sound

That the earth owes.471 I hear it now above me.

PROSPERO

PROSPERO The fringèd curtains

472 of thine eye advance

And say what thou see’st yond.473

MIRANDA

MIRANDA What is’t? A spirit?

475

475 Lord, how it looks about! Believe me, sir,

It carries a brave476 form. But ’tis a spirit.

PROSPERO

PROSPERO No, wench: it eats, and sleeps, and hath such senses

As we have, such. This gallant478 which thou see’st

Was in the wreck: and, but479 he’s something stained

480

480 With grief — that’s beauty’s canker480 — thou mightst call him

A goodly481 person: he hath lost his fellows

And strays about to find ’em.

MIRANDA

MIRANDA I might call him

A thing divine, for nothing natural484

485

485 I ever saw so noble.

PROSPERO

PROSPERO It goes on, I see,

Aside

As my soul prompts487 it.— Spirit, fine spirit: I’ll free thee To Ariel

Within two days for this.

FERDINAND

FERDINAND Most sure, the goddess

490

490 On whom these airs490 attend! Vouchsafe my prayer

May know if you remain491 upon this island,

And that you will some good instruction give

How I may bear me493 here: my prime request,

Which I do last pronounce, is — O you wonder!494 —

495

495 If you be maid495 or no?

MIRANDA

MIRANDA No wonder, sir,

But certainly a maid.

FERDINAND

FERDINAND My language? Heavens!

I am the best499 of them that speak this speech,

500

500 Were I but where500 ’tis spoken.

PROSPERO

PROSPERO How? The best?

What wert thou if the King of Naples heard thee?

FERDINAND

FERDINAND A single thing,

503 as I am now, that wonders

To hear thee speak of Naples. He504 does hear me:

505

505 And that he does, I weep. Myself am Naples,

Who with mine eyes, never since at ebb,506 beheld

The king my father wrecked.

MIRANDA

MIRANDA Alack, for mercy!

FERDINAND

FERDINAND Yes, faith, and all his lords, the Duke of Milan

510

510 And his brave son510 being twain.

PROSPERO

PROSPERO The Duke of Milan

Aside

And his more braver daughter could control512 thee

If now ’twere fit to do’t. At the first sight

They have changed eyes.514— Delicate Ariel, To Ariel

515

515 I’ll set thee free for this.— A word, good sir, To Ferdinand

I fear you have done516 yourself some wrong: a word.

MIRANDA

MIRANDA Why speaks my father so ungently?

517 This

Is the third man that e’er I saw: the first

That e’er I sighed for. Pity move my father

520

520 To be inclined my way.

FERDINAND

FERDINAND O, if a virgin,

And your522 affection not gone forth, I’ll make you

The Queen of Naples.

PROSPERO

PROSPERO Soft,

524 sir,

one word more.—

525

525 They are both in either’s525 powers: but this swift business Aside

I must uneasy526 make, lest too light winning

Make the prize light.— One word more: I charge527 thee To Ferdinand

That thou attend528 me: thou dost here usurp

The name thou ow’st not,529 and hast put thyself

530

530 Upon this island as a spy, to win it

From me, the lord on’t.531

FERDINAND

FERDINAND No, as I am a man.

MIRANDA

MIRANDA There’s nothing ill can dwell in such a temple:

533

If the ill-spirit have so fair a house,

535

535 Good things will strive to dwell with’t.

PROSPERO

PROSPERO Follow me.—

To Ferdinand

Speak not you for him: he’s a traitor.— Come: To Miranda/To Ferdinand

I’ll manacle thy neck and feet together:

Seawater shalt thou drink: thy food shall be

540

540 The fresh-brook mussels,540 withered roots and husks

Wherein the acorn cradled. Follow.

I will resist such entertainment543 till

Mine enemy has more power.

He draws, and is charmed from moving

545

545 MIRANDA

MIRANDA O dear father,

Make not too rash a trial of him, for

He’s gentle,547 and not fearful.

PROSPERO

PROSPERO What, I say,

My foot549 my tutor?— Put thy sword up, traitor: To Ferdinand

550

550 Who mak’st a show but dar’st not strike, thy conscience

Is so possessed with guilt. Come from thy ward,551

For I can here disarm thee with this stick, Brandishes his staff

And make thy weapon drop.

MIRANDA

MIRANDA Beseech you, father.

Kneels or attempts to stop him

555

555 PROSPERO

PROSPERO Hence! Hang not on my garments.

MIRANDA

MIRANDA Sir, have pity:

I’ll be his surety.557

PROSPERO

PROSPERO Silence! One word more

Shall make me chide559 thee, if not hate thee. What,

560

560 An advocate for an impostor? Hush!

Thou think’st there is no more such shapes561 as he,

Having seen but him and Caliban. Foolish wench,

To563 th’most of men this is a Caliban,

And they to him are angels.

565

565 MIRANDA

MIRANDA My affections

Are then most humble: I have no ambition

To see a goodlier man.

PROSPERO

PROSPERO Come on, obey:

To Ferdinand

Thy nerves569 are in their infancy again

570

570 And have no vigour570 in them.

FERDINAND

FERDINAND So they are:

My spirits,572 as in a dream, are all bound up.

My father’s loss, the weakness which I feel,

The wreck of all my friends, nor this man’s threats,

575

575 To whom I am subdued, are but light to me,

Might I but through576 my prison once a day

Behold this maid: all corners else577 o’th’earth

Let liberty make use of: space enough

Have I in such a prison.

580

580 PROSPERO

PROSPERO It works.— Come on.—

Aside/To Ferdinand

Thou hast done well, fine Ariel!— Follow me.— To Ariel/To Ferdinand

Hark what thou else shalt do me.582 To Ariel

MIRANDA

MIRANDA Be of comfort:

My father’s of a better nature, sir,

585

585 Than he appears by speech: this is unwonted585

Which now came from him.

PROSPERO

PROSPERO Thou shalt be as free

To Ariel

As mountain winds; but then588 exactly do

All points of my command.

590

590 ARIEL

ARIEL To th’syllable.

PROSPERO

PROSPERO Come, follow.— Speak not for him.

To Ferdinand/To Miranda

Exeunt

Act 2 Scene 1

running scene 3

Enter Alonso, Sebastian, Antonio, Gonzalo, Adrian, Francisco and others

GONZALO

GONZALO Beseech you, sir, be merry; you have cause —

To Alonso

So have we all — of joy, for our escape

Is much beyond3 our loss. Our hint of woe

Is common: every day some sailor’s wife,

5

5 The masters5 of some merchant, and the merchant

Have just our theme of woe. But for the miracle —

I mean our preservation — few in millions

Can speak like us: then wisely, good sir, weigh8

Our sorrow with our comfort.

ALONSO

ALONSO Prithee, peace.

10

SEBASTIAN

SEBASTIAN He receives comfort like cold porridge.

Antonio and Sebastian speak apart

ANTONIO

ANTONIO The visitor

12 will not give him o’er so.

SEBASTIAN

SEBASTIAN Look, he’s winding up the watch of his wit:

13 by and by it will strike.

GONZALO

GONZALO Sir—

To Alonso

SEBASTIAN

SEBASTIAN One: tell.

15

GONZALO

GONZALO When every grief is entertained

16 that’s offered, comes to th’entertainer—

SEBASTIAN

SEBASTIAN A dollar.

17 Aside to Antonio, but overheard by Gonzalo

GONZALO

GONZALO Dolour

18 comes to him, indeed: you have spoken truer than you purposed.

SEBASTIAN

SEBASTIAN You have taken it wiselier

19 than I meant you should.

GONZALO

GONZALO Therefore, my lord—

To Alonso

ANTONIO

ANTONIO Fie, what a spendthrift is he of his tongue!

ALONSO

ALONSO I prithee, spare.

22 To Gonzalo

GONZALO

GONZALO Well, I have done: but yet—

SEBASTIAN

SEBASTIAN He will be talking.

ANTONIO

ANTONIO Which, of he or Adrian, for a good wager, first begins to crow?

25

SEBASTIAN

SEBASTIAN The old cock.

ANTONIO

ANTONIO The cockerel.

27

SEBASTIAN

SEBASTIAN Done. The wager?

28

ANTONIO

ANTONIO A laughter.

29

SEBASTIAN

SEBASTIAN A match!

ADRIAN

ADRIAN Though this island seem to be desert

31—

SEBASTIAN

SEBASTIAN Ha,

32 ha, ha!

ANTONIO

ANTONIO So: you’re paid.

ADRIAN

ADRIAN Uninhabitable and almost inaccessible—

ANTONIO

ANTONIO He could not miss’t.

ADRIAN

ADRIAN It must needs be of subtle,

38 tender and delicate temperance.

ANTONIO

ANTONIO Temperance was a delicate

39 wench.

SEBASTIAN

SEBASTIAN Ay, and a subtle,

40 as he most learnedly delivered.

ADRIAN

ADRIAN The air breathes upon us here most sweetly.

SEBASTIAN

SEBASTIAN As if it had lungs, and rotten ones.

ANTONIO

ANTONIO Or as ’twere perfumed by a fen.

43

GONZALO

GONZALO Here is everything advantageous to life.

ANTONIO

ANTONIO True: save

45 means to live.

SEBASTIAN

SEBASTIAN Of that there’s none, or little.

GONZALO

GONZALO How lush and lusty

47 the grass looks. How green!

ANTONIO

ANTONIO The ground indeed is tawny.

48

SEBASTIAN

SEBASTIAN With an eye

49 of green in’t.

ANTONIO

ANTONIO He misses not much.

SEBASTIAN

SEBASTIAN No: he doth but mistake the truth totally.

GONZALO

GONZALO But the rarity

52 of it is — which is indeed almost beyond credit—

SEBASTIAN

SEBASTIAN As many vouched

53 rarities are.

GONZALO

GONZALO —That our garments, being, as they were, drenched in the sea, hold notwithstanding their freshness and glosses, being rather new-dyed

55 than stained with salt water.

ANTONIO

ANTONIO If but one of his pockets could speak, would it not say he lies?

SEBASTIAN

SEBASTIAN Ay, or very falsely pocket up

58 his report.

GONZALO

GONZALO Methinks our garments are now as fresh as when we put them on first in Afric,

60 at the marriage of the king’s fair daughter Claribel to the King of Tunis.

SEBASTIAN

SEBASTIAN ’Twas a sweet marriage, and we prosper well in our return.

ADRIAN

ADRIAN Tunis was never graced before with such a paragon to their queen.

GONZALO

GONZALO Not since widow Dido’s

63 time.

ANTONIO

ANTONIO Widow! A pox o’that! How

64 came that ‘widow’ in? Widow Dido!

SEBASTIAN

SEBASTIAN What if he had said ‘widower Aeneas’

65 too? Good lord, how you take it!

ADRIAN

ADRIAN ‘Widow Dido’, said you? You make me study of

66 that: she was of Carthage, not of Tunis.

GONZALO

GONZALO This

68 Tunis, sir, was Carthage.

GONZALO

GONZALO I assure you, Carthage.

ANTONIO

ANTONIO His word is more than the miraculous harp.

71

SEBASTIAN

SEBASTIAN He hath raised the wall and houses too.

ANTONIO

ANTONIO What impossible matter will he make easy next?

SEBASTIAN

SEBASTIAN I think he will carry this island home in his pocket and give it his son for an apple.

ANTONIO

ANTONIO And, sowing the kernels

76 of it in the sea, bring forth more islands.

ANTONIO

ANTONIO Why, in good time.

GONZALO

GONZALO Sir,

To Alonso we were talking that our garments seem now as fresh as when we were at Tunis at the marriage of your daughter, who is now queen.

ANTONIO

ANTONIO And the rarest

81 that e’er came there.

SEBASTIAN

SEBASTIAN Bate,

82 I beseech you, widow Dido.

ANTONIO

ANTONIO O, widow Dido? Ay, widow Dido.

83

GONZALO

GONZALO Is not, sir, my doublet

84 as fresh as the first day I wore it? I mean, in a sort—

ANTONIO

ANTONIO That sort

85 was well fished for.

GONZALO

GONZALO —When I wore it at your daughter’s marriage.

ALONSO

ALONSO You cram these words into mine ears against

The stomach88 of my sense. Would I had never

Married my daughter there: for, coming thence,

90

90 My son is lost and — in my rate90 — she too,

Who is so far from Italy removed

I ne’er again shall see her. O thou mine heir

Of Naples and of Milan, what strange fish

Hath made his meal on thee?

95

95 FRANCISCO

FRANCISCO Sir, he may live:

I saw him beat the surges96 under him,

And ride upon their backs; he trod the water,

Whose enmity he flung aside, and breasted

The surge most swoll’n that met him: his bold head

100

100 ’Bove the contentious waves he kept, and oared100

Himself with his good arms in lusty101 stroke

To th’shore, that o’er his wave-worn basis102 bowed,

As103 stooping to relieve him: I not doubt

He came alive to land.

105

105 ALONSO

ALONSO No, no, he’s gone.

SEBASTIAN

SEBASTIAN Sir, you may thank yourself for this great loss,

To Alonso

That would not bless our Europe with your daughter,

But rather loose108 her to an African,

Where she, at least, is banished from your eye,

110

110 Who110 hath cause to wet the grief on’t.

ALONSO

ALONSO Prithee, peace.

SEBASTIAN

SEBASTIAN You were kneeled to and importuned

112 otherwise

By all of us: and the fair soul herself

Weighed between loathness114 and obedience at

115

115 Which115 end o’th’beam should bow. We have lost your son,

I fear, forever: Milan and Naples have

More widows in them of this business’ making

Than we bring men to comfort them.

The fault’s your own.

120

120 ALONSO

ALONSO So is the dear’st

120 o’th’loss.

GONZALO

GONZALO My lord Sebastian,

The truth you speak doth lack some gentleness,

And time123 to speak it in: you rub the sore,

When you should bring the plaster.

125

125 SEBASTIAN

SEBASTIAN Very well.

ANTONIO

ANTONIO And most chirurgeonly.

126

GONZALO

GONZALO It is foul weather in us all, good sir,

To Alonso

When you are cloudy.

SEBASTIAN

SEBASTIAN Foul weather?

130

130 ANTONIO

ANTONIO Very foul.

GONZALO

GONZALO Had I plantation

131 of this isle, my lord—

ANTONIO

ANTONIO He’d sow’t with nettle-seed.

132

SEBASTIAN

SEBASTIAN Or docks, or mallows.

GONZALO

GONZALO And were the king on’t, what would I do?

135

135 SEBASTIAN

SEBASTIAN Scape being drunk for want

135 of wine.

GONZALO

GONZALO I’th’commonwealth I would by

136 contraries

Execute all things: for no kind of traffic137

Would I admit: no name of magistrate:

Letters139 should not be known: riches, poverty,

140

140 And use of service,140 none: contract, succession,

Bourn,141 bound of land, tilth, vineyard, none:

No use of metal, corn, or wine, or oil:

No occupation, all men idle, all:

And women too, but innocent and pure:

145

145 No sovereignty.

SEBASTIAN

SEBASTIAN Yet he would be king on’t.

ANTONIO

ANTONIO The latter end of his commonwealth forgets the beginning.

GONZALO

GONZALO All things in common

148 nature should produce

Without sweat or endeavour: treason, felony,

150

150 Sword, pike,150 knife, gun, or need of any engine,

Would I not have: but nature should bring forth,

Of it own kind, all foison,152 all abundance,

To feed my innocent people.

SEBASTIAN

SEBASTIAN No marrying ’mong his subjects?

155

155 ANTONIO

ANTONIO None, man, all idle: whores and knaves.

GONZALO

GONZALO I would with such perfection govern, sir,

T’excel the golden age.157

SEBASTIAN

SEBASTIAN ’Save his majesty!

ANTONIO

ANTONIO Long live Gonzalo!

Bowing or doffing hats

GONZALO

GONZALO And — do you mark

160 me, sir?

ALONSO

ALONSO Prithee, no more: thou dost talk nothing to me.

GONZALO

GONZALO I do well believe your highness: and did it to minister occasion

162 to these gentlemen, who are of such sensible

163 and nimble lungs that they always use to laugh at nothing.

ANTONIO

ANTONIO ’Twas you we laughed at.

GONZALO

GONZALO Who in this kind of merry fooling am nothing to you: so you may continue and laugh at nothing still.

ANTONIO

ANTONIO What a blow was there given!

SEBASTIAN

SEBASTIAN An

169 it had not fallen flat-long.

GONZALO

GONZALO You are gentlemen of brave metal:

170 you would lift the moon out of her sphere,

171 if she would continue in it five weeks without changing.

Enter Ariel [invisible] playing solemn music

SEBASTIAN

SEBASTIAN We would so, and then go a-batfowling.

172

ANTONIO

ANTONIO Nay, good my lord, be not angry.

GONZALO

GONZALO No, I warrant

174 you: I will not adventure my discretion so weakly. Will you laugh me asleep, for I am very heavy?

175

ANTONIO

ANTONIO Go sleep, and hear us.

All sleep except Alonso, Sebastian, and Antonio

ALONSO

ALONSO What, all so soon asleep? I wish mine eyes

Would, with themselves, shut up my thoughts.

I find they are inclined to do so.

180

180 SEBASTIAN

SEBASTIAN Please you, sir,

Do not omit181 the heavy offer of it.

It seldom visits sorrow: when it doth, it is a comforter.

ANTONIO

ANTONIO We two, my lord, will guard your person

While you take your rest, and watch your safety.

185

185 ALONSO

ALONSO Thank you. Wondrous heavy.

He sleeps

SEBASTIAN

SEBASTIAN What a strange drowsiness possesses them!

[Exit Ariel]

ANTONIO

ANTONIO It is the quality o’th’climate.

Doth it not then our eyelids sink? I find

190

190 Not myself disposed to sleep.

ANTONIO

ANTONIO Nor I: my spirits are nimble.

They fell together all, as192 by consent

They dropped, as by a thunder-stroke. What might,

Worthy Sebastian? O, what might? — No more.—

195

195 And yet, methinks I see it in thy face,

What thou shouldst be: th’occasion speaks196 thee, and

My strong imagination sees a crown

Dropping upon thy head.

SEBASTIAN

SEBASTIAN What? Art thou waking?

199

200

200 ANTONIO

ANTONIO Do you not hear me speak?

SEBASTIAN

SEBASTIAN I do, and surely

It is a sleepy language and thou speak’st

Out of thy sleep. What is it thou didst say?

This is a strange repose, to be asleep

205

205 With eyes wide open: standing, speaking, moving,

And yet so fast asleep.

ANTONIO

ANTONIO Noble Sebastian,

Thou let’st thy fortune sleep — die, rather: wink’st208

Whiles thou art waking.

210

210 SEBASTIAN

SEBASTIAN Thou dost snore distinctly:

210

There’s meaning in thy snores.

ANTONIO

ANTONIO I am more serious than my custom:

212 you

Must be so too, if heed213 me: which to do

Trebles thee o’er.214

215

215 SEBASTIAN

SEBASTIAN Well, I am standing water.

215

ANTONIO

ANTONIO I’ll teach you how to flow.

SEBASTIAN

SEBASTIAN Do so: to ebb

Hereditary sloth218 instructs me.

220

220 If220 you but knew how you the purpose cherish

Whiles thus you mock it: how in stripping it

You more invest222 it. Ebbing men, indeed,

Most often, do so near the bottom run

By their own fear, or sloth.

225

225 SEBASTIAN

SEBASTIAN Prithee, say on:

225

The setting226 of thine eye and cheek proclaim

A matter227 from thee; and a birth, indeed,

Which throes228 thee much to yield.

ANTONIO

ANTONIO Thus, sir:

230

230 Although this lord230 of weak remembrance, this,

Who shall be of231 as little memory

When he is earthed,232 hath here almost persuaded —

For he’s a spirit of233 persuasion, only

Professes to persuade — the king his son’s alive:

235

235 ’Tis as impossible that he’s undrowned

As he that sleeps here swims.

SEBASTIAN

SEBASTIAN I have no hope

That he’s undrowned.

ANTONIO

ANTONIO O, out of that ‘no hope’

240

240 What great hope have you! No hope that way is

Another way so high a hope,241 that even

Ambition242 cannot pierce a wink beyond,

But doubt discovery there. Will you grant with me

That Ferdinand is drowned?

245

245 SEBASTIAN

SEBASTIAN He’s gone.

ANTONIO

ANTONIO Then, tell me: who’s the next heir of Naples?

SEBASTIAN

SEBASTIAN Claribel.

ANTONIO

ANTONIO She that is Queen of Tunis: she that dwells

Ten leagues249 beyond man’s life: she that from Naples

250

250 Can have no note,250 unless the sun were post —

The man i’th’moon’s too slow — till new-born chins

Be rough and razorable: she that from whom252

We all were sea-swallowed, though some cast253 again —

And by that destiny — to perform an act

255

255 Whereof255 what’s past is prologue, what to come

In yours and my discharge.256

SEBASTIAN

SEBASTIAN What stuff

257 is this? How say you?

’Tis true, my brother’s daughter’s Queen of Tunis:

So is she heir of Naples, ’twixt which regions

260

260 There is some space.260

ANTONIO

ANTONIO A space whose every cubit

261

Seems to cry out, ‘How shall that Claribel

Measure us back263 to Naples? Keep in Tunis,

And let Sebastian wake.264’ Say this were death

265

265 That now hath seized them: why, they were no worse

Than now they are. There be that can rule Naples

As well as he267 that sleeps: lords that can prate

As amply and unnecessarily

As this Gonzalo: I myself could make269

270

270 A chough of as deep chat. O, that you bore270

The mind that I do! What a sleep were this

For your advancement! Do you understand me?

SEBASTIAN

SEBASTIAN Methinks I do.

ANTONIO

ANTONIO And how does your content

274

275

275 Tender275 your own good fortune?

SEBASTIAN

SEBASTIAN I remember

You did supplant277 your brother Prospero.

And look how well my garments279 sit upon me,

280

280 Much feater280 than before. My brother’s servants

Were then my fellows:281 now they are my men.

SEBASTIAN

SEBASTIAN But for your conscience.

ANTONIO

ANTONIO Ay, sir: where lies that? If ’twere a kibe,

283

’Twould put me to284 my slipper: but I feel not

285

285 This deity285 in my bosom: twenty consciences

That stand ’twixt me and Milan, candied286 be they,

And melt ere they molest! Here lies your brother,

No better than the earth he lies upon,

If he were that which now he’s like — that’s dead —

290

290 Whom I with this obedient steel — three inches of it — Touching sword or dagger

Can lay to bed forever: whiles you, doing thus,

To the perpetual wink292 for aye might put

This ancient morsel,293 this Sir Prudence, who

Should not294 upbraid our course. For all the rest,

295

295 They’ll take suggestion as a cat laps milk:

They’ll tell296 the clock to any business that

We say befits the hour.

SEBASTIAN

SEBASTIAN Thy case, dear friend,

Shall be my precedent. As thou got’st Milan,

300

300 I’ll come by Naples. Draw thy sword: one stroke

Shall free thee from the tribute301 which thou payest,

And I the king shall love thee.

ANTONIO

ANTONIO Draw together:

And when I rear304 my hand, do you the like,

305

305 To fall it on Gonzalo.

SEBASTIAN

SEBASTIAN O, but one word.

They talk apart

Enter Ariel [invisible] with music and song

ARIEL

ARIEL My master through his art foresees the danger

To Gonzalo, who still sleeps

That you, his friend, are in, and sends me forth —

For else his project309 dies — to keep them living.

310

310 While you here do snoring lie,

Sings in Gonzalo’s ear

Open-eyed conspiracy

His time312 doth take.

If of life you keep a care,

Shake off slumber, and beware:

315

315 Awake, awake!

ANTONIO

ANTONIO Then let us both be sudden.

Antonio and Sebastian draw their swords

GONZALO

GONZALO Now, good angels preserve the king!

Waking

ALONSO

ALONSO Why, how now? Ho, awake! Why are you drawn?

The others wake

Wherefore this ghastly319 looking?

320

320 GONZALO

GONZALO What’s the matter?

SEBASTIAN

SEBASTIAN Whiles we stood here securing your repose,

Even now, we heard a hollow burst of bellowing

Like bulls, or rather lions: did’t not wake you?

It struck mine ear most terribly.

325

325 ALONSO

ALONSO I heard nothing.

ANTONIO

ANTONIO O, ’twas a din to fright a monster’s ear,

To make an earthquake! Sure it was the roar

Of a whole herd of lions.

ALONSO

ALONSO Heard you this, Gonzalo?

330

330 GONZALO

GONZALO Upon mine honour, sir, I heard a humming,

And that a strange one too, which did awake me:

I shaked you, sir, and cried: as mine eyes opened,

I saw their weapons drawn: there was a noise,

That’s verily.334 ’Tis best we stand upon our guard,

335

335 Or that we quit this place: let’s draw our weapons.

ALONSO

ALONSO Lead off this ground, and let’s make further search

For my poor son.

GONZALO

GONZALO Heavens keep him from these beasts!

For he is sure i’th’island.

340

340 ALONSO

ALONSO Lead away.

ARIEL

ARIEL Prospero, my lord, shall know what I have done.

So, king, go safely on to seek thy son.

Exeunt [separately]

Act 2 Scene 2

running scene 4

Enter Caliban with a burden of wood. A noise of thunder heard

CALIBAN

CALIBAN All the infections that the sun sucks up

From bogs, fens, flats,2 on Prosper fall, and make him

By inch-meal3 a disease. His spirits hear me,

And yet I needs must curse. But they’ll nor4 pinch,

5

5 Fright me with urchin-shows,5 pitch me i’th’mire,

Nor lead me like a firebrand6 in the dark

Out of my way, unless he bid ’em: but

For every trifle are they set upon me,

Sometime like apes, that mow9 and chatter at me,

10

10 And after bite me: then like hedgehogs, which

Lie tumbling in my barefoot way and mount

Their pricks at my footfall: sometime am I

All wound13 with adders, who with cloven tongues

Do hiss me into madness.

Enter Trinculo

Lo,14 now, lo!

15

15 Here comes a spirit of his, and to torment me

For bringing wood in slowly. I’ll fall flat:

Perchance he will not mind17 me. Lies down and covers himself with his cloak

TRINCULO

TRINCULO Here’s neither bush nor shrub to bear off

18 any weather at all, and another storm brewing: I hear it sing i’th’wind: yond same black cloud, yond huge one, looks like a foul bombard

20 that would shed his liquor. If it should thunder as it did before, I know not where to hide my head: yond same cloud cannot choose but fall by pailfuls.

Sees Caliban What have we here? A man or a fish? Dead or alive? A fish, he smells like a fish: a very ancient and fishlike smell: a kind of not-of-the-newest poor-John.

24 A strange fish! Were I in England now — as once I was — and had but this fish painted,

25 not a holiday fool there but would give a piece of silver: there would this monster make a man:

26 any strange beast there makes a man: when they will not give a doit

27 to relieve a lame beggar, they will lay out ten to see a dead Indian.

28 Legged like a man and his fins like arms! Warm, o’my troth! I do now let loose

29 my opinion, hold it no longer: this is no fish, but an islander that hath lately suffered by a thunderbolt.

Thunder Alas, the storm is come again! My best way is to creep under his gaberdine:

31 there is no other shelter hereabout. Misery acquaints a man with strange bedfellows: I will here shroud

33 till the dregs of the storm be past.

Trinculo gets under Caliban’s cloak

Enter Stephano, singing With a bottle in his hand

STEPHANO

STEPHANO I shall no more to sea, to sea:

35

35 Here shall I die ashore—

This is a very scurvy36 tune to sing at a man’s funeral: well, here’s my comfort.

Drinks

The master, the swabber,38 the boatswain and I,

Sings

The gunner and his mate,

40

40 Loved Mall, Meg and Marian and Margery,

But none of us cared for Kate.

For she had a tongue with a tang,42

Would cry to a sailor, ‘Go hang!’

She loved not the savour44 of tar nor of pitch,

45

45 Yet a tailor45 might scratch her where’er she did itch:

Then to sea, boys, and let her go hang!

This is a scurvy tune too: but here’s my comfort.

Drinks

CALIBAN

CALIBAN Do not torment me: O!

STEPHANO

STEPHANO What’s the matter?

49 Have we devils here? Do you put tricks upon’s with savages and men of Ind,

50 ha? I have not scaped drowning to be afeard now of your four legs: for it hath been said, ‘As proper

51 a man as ever went on four legs, cannot make him give ground

52’: and it shall be said so again, while Stephano breathes at’nostrils.

53

CALIBAN

CALIBAN The spirit torments me: O!

STEPHANO

STEPHANO This is some monster of the isle with four legs, who hath got, as I take it, an ague.

56 Where the devil should he learn our language? I will give him some relief,