THE TAMING OF THE SHREW

The novelist Vladimir Nabokov once wrote that “reality” is a word that only has meaning when it is placed in quotation marks. The physicist’s “reality” is not the same as the biochemist’s, the secular humanist’s as the religious fundamentalist’s. Dare one say the woman’s is not the same as the man’s? In a culture where the conception of inherent sexual difference is regarded as a mere prejudice, as a forbidden thought (regardless of the “reality” revealed by molecular biology and neuroanatomy), The Taming of the Shrew is not likely to be one of Shakespeare’s most admired plays. Its presentation of female subordination presents the same kind of awkwardness for liberal sensibilities that the representation of Shylock does in the post-Holocaust world. At face value, the play proposes that desirable women are quiet and submissive, whereas women with spirit must be “tamed” through a combination of physical and mental abuse. Necessary tools may include starvation, sense deprivation, and the kind of distortion of “reality” that is practiced in totalitarian regimes.

Thus O’Brien to Winston Smith in George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four: “How many fingers am I holding up?” In this “reality” the correct answer is not the actual number but the number that the torturer says he is holding up. There is a precise analogy on the road back to Padua, after Kate has undergone her taming in the secluded country house where no neighbor will hear her cries:

PETRUCHIO

PETRUCHIO I say it is the moon.

KATE

KATE I know it is the moon.

PETRUCHIO

PETRUCHIO Nay, then you lie. It is the blessèd sun.

KATE

KATE Then, God be blessed, it is the blessèd sun.

But sun it is not, when you say it is not,

And the moon changes even as your mind.

What you will have it named, even that it is,

And so it shall be so for Katherine.

HORTENSIO

HORTENSIO Petruchio, go thy ways, the field is won.

She has been bent to her husband’s will. She is now ready to demonstrate that she is prepared to love, serve, and obey him. She knows her place: “Such duty as the subject owes the prince / Even such a woman oweth to her husband.” She offers to place her hand beneath her husband’s foot. The shrew is tamed.

The younger dramatist John Fletcher, who was Shakespeare’s collaborator in his final years, clearly thought that this harsh ending needed a riposte. He wrote a sequel, The Woman’s Prize; or, The Tamer Tamed, in which Kate has died and Petruchio remarried, only to find his new wife giving him a taste of his own medicine by means of the time-honored device of refusing to sleep with him until he submits to her will. Kate’s sister Bianca plays the role of colonel in a war between the sexes, which the women win, thus proving that it was an act of folly for Petruchio to tyrannize over his first wife in Shakespeare’s play.

In Shakespeare’s time, it was absolutely orthodox to believe that a man was head of the household, as the monarch was head of state and God was head of the cosmos. “My foot my tutor?” says Prospero in The Tempest when his daughter Miranda presumes to speak out of turn: if the man was the head, the girl-child was the foot, just as in Coriolanus a plebeian is nothing more than the “big toe” of the commonwealth. Kate’s readying of her hand to be trodden upon turns the analogy between social and bodily hierarchy into a stage image. But she is going much further than she should: the wife was not supposed to be beneath the foot, she was supposed to be the heart of the household. Instead of crowing in his triumph, Petruchio says “kiss me, Kate” for the third time, giving Cole Porter a title for his reimagining of the story in the cheerful mode of a musical.

Nabokov placed the word “reality” in quotation marks not because he was a cultural relativist, but because he was an aesthete. That is to say, he did not believe that art was merely a reflection, a mirror, of a pre-existent “reality.” Art shapes the way in which we perceive ourselves and the world. “Falling in love” is not only the work of molecular change in the brain, but also a set of behaviors learned from the romantic fictions of page, stage—now screen—and cultural memory. One of the tricks of great art is to draw attention to its own artificiality and in so doing paradoxically assert that its “reality” is as real as anything in the quotidian world of its audience. Shakespeare’s taste for plays-within-the-play and allusions to the theatricality of the world, Mozart’s witty quotations of the clichés of operatic convention, and Nabokov’s magical wordplay all fulfill this function.

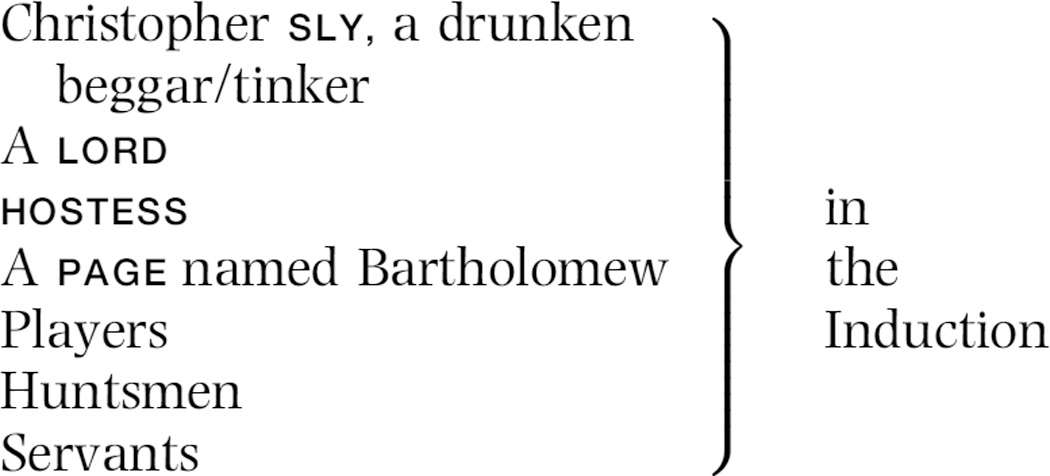

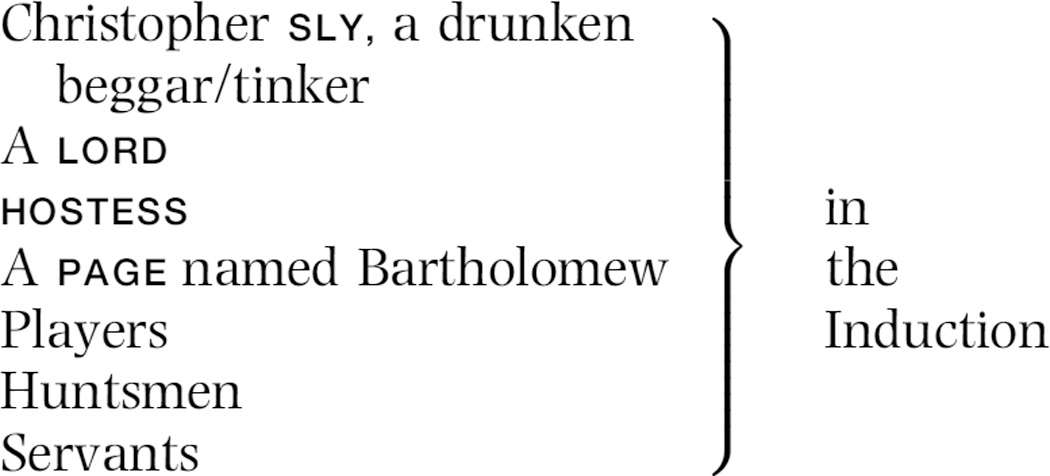

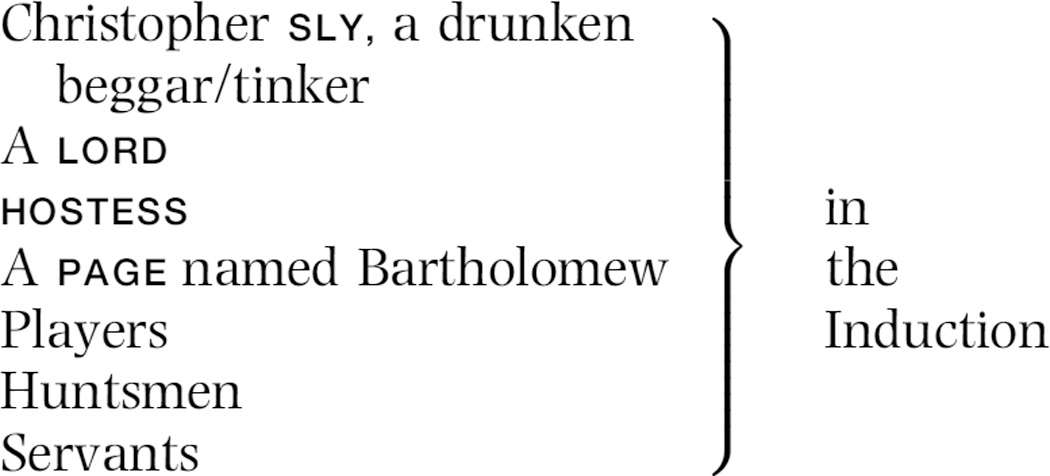

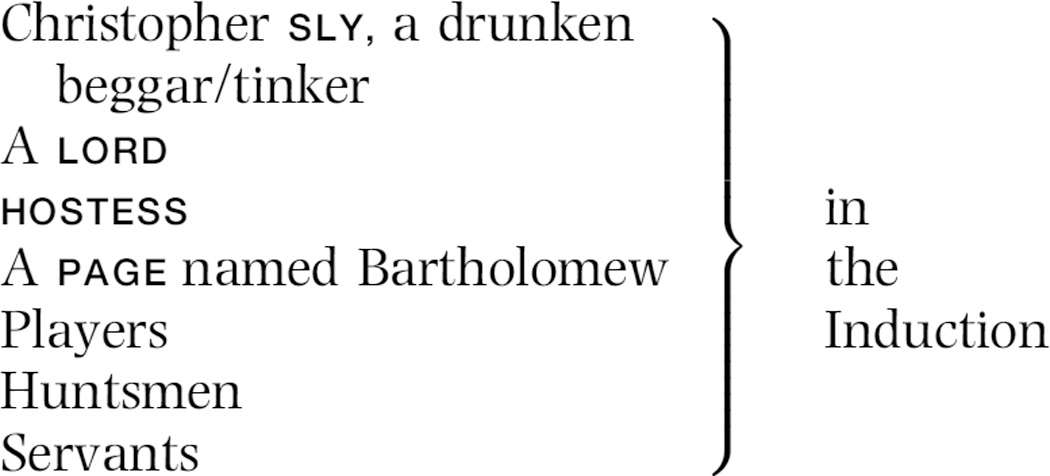

Sometimes, though, the opposite device is used: an artist puts quotation marks around a work in order to say “Don’t take this too seriously, don’t mistake its feigning for ‘reality.’ ” The Taming of the Shrew is such a work: the opening scenes with Christopher Sly place the entire play within quotation marks. The “induction” presents a series of wish-fulfillment fantasies to a drunken tinker: the fantasy that he is a lord, that he has a beautiful young wife, that scenes of erotic delight can be presented for his delectation, and that a company of professional players will stage “a kind of history” for his sole benefit, in order to frame his mind to “mirth and merriment” while teaching him how to tame a shrewish wife. But Sly is not a lord and the “wife” who watches with him is not a woman but a cross-dressed boy (which reminds us that in Shakespeare’s working world the Kate who is humiliated by Petruchio was also not a woman but a cross-dressed boy-actor). The effect of the frame is to “distance” the action and so suggest that it does not present the “reality” of proper marital relations. If Sly is not a lord and the pageboy not a wife, then this is not how to tame a shrew.

In the surviving script of the play, Sly and the pageboy disappear after the first act, presumably because Shakespeare’s acting company was not large enough to waste several members of the cast sitting in the gallery as spectators all the way through. But in an anonymously published play of 1594 called The Taming of a Shrew, which seems to be some sort of adaptation, reconstruction, or variant version, the Christopher Sly “frame” is maintained throughout the action by means of a series of brief interludes and an epilogue. This version ends with the tinker going home claiming that the play has taught him how to tame a shrew and thus to handle his own wife. But the tapster knows better: “your wife will course [thrash] you for dreaming here tonight.” The hungover Sly is in no position to tame anybody; he will return home and be soundly beaten by his wife. Kate’s speech propounds the patriarchal ideal of marriage, but in A Shrew the Slys’ is a union that reveals this ideology’s distance from “reality”; its implied resolution, with the woman on top, intimates that “real” housewives are not silent and obedient, and plays cannot teach husbands to tame them into submission.

We do not need the epilogue of the anonymously published play to see that Shakespeare’s ending is more complicated and ironic than first appears. Having been outwitted in his courtship of Bianca, Hortensio marries the widow for her money. The latter shows signs of frowardness and has to be lectured by Kate. The first half of Kate’s famous submission speech is spoken in the singular, addressed specifically to the widow and not to womankind in general: “Thy husband is thy lord, thy life, thy keeper, / Thy head, thy sovereign: one that cares for thee.” The contextual irony of this is not always appreciated: in contradistinction to Kate’s prescriptions, in this marriage it will be the wife, the wealthy widow, who provides the “maintenance”; Hortensio will be spared the labors of a breadwinner. According to Kate, all a husband asks from a wife is love, good looks, and obedience; these are said to be “Too little payment for so great a debt.” But the audience knows that in this case the debt is all Hortensio’s. Besides, he has said earlier that he is no longer interested in woman’s traditional attribute of “beauteous looks”—all he wants is the money. Kate’s vision of obedience is made to look oddly irrelevant to the very marriage upon which she is offering advice.

Then there is Kate’s sister. Petruchio’s “taming school” is played off against the attempts by Lucentio and Hortensio to gain access to Bianca by disguising themselves as schoolmasters. In the scene in which Lucentio courts her in the guise of a Latin tutor, the woman gives as good as she gets. She is happy to flirt with her supposed teacher over Ovid’s erotic manual The Art of Love. This relationship offers a model of courtship and marriage built on mutual desire and consent; Bianca escapes her class of sixteenth-century woman’s usual fate of being married to a partner of the father’s choice, such as rich old Gremio. If anything, Bianca is the dominant partner at the end. She is not read a lecture by Kate, as the widow is, and she gets the better of her husband in their final on-stage exchange. Like Beatrice in Much Ado About Nothing, she more than matches her man in the art of wordplay. One almost wonders if she would not be better matched with the pretended rather than the “real” Lucentio, that is to say the clever servant Tranio who oils the wheels of the plot and sometimes threatens to steal the show.

The double plot is a guarantee that, despite the subduing of Kate, the play is no uncomplicated apology for shrew-taming. But is Kate really subdued? Or is her submission all part of the game that she and Petruchio have been playing out? It is their marriage, not the other ones, that compels the theater audience. A woman with Kate’s energies would be bored by a conventional lover such as Lucentio. She and Petruchio are well matched because they are both of “choleric” temperament; their fierce tempers are what make them attractive to each other and charismatic to us. They seem to know they are born for each other from the moment in their first private encounter when they share a joke about oral sex (“with my tongue in your tail”). “Where two raging fires meet together” there may not be an easy marriage, but there will certainly not be a dull match and a passive wife. In the twentieth century the roles seemed ready made for Richard Burton and Elizabeth Taylor.

KEY FACTS

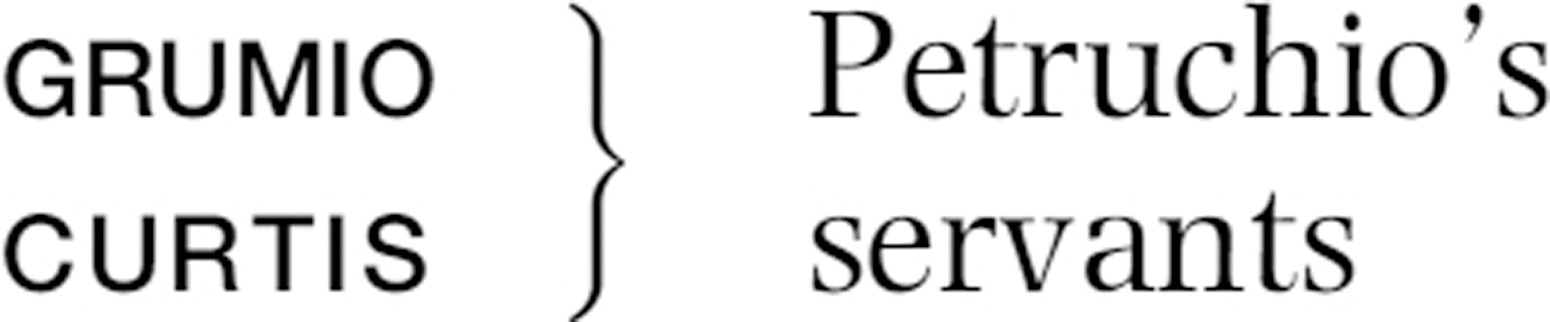

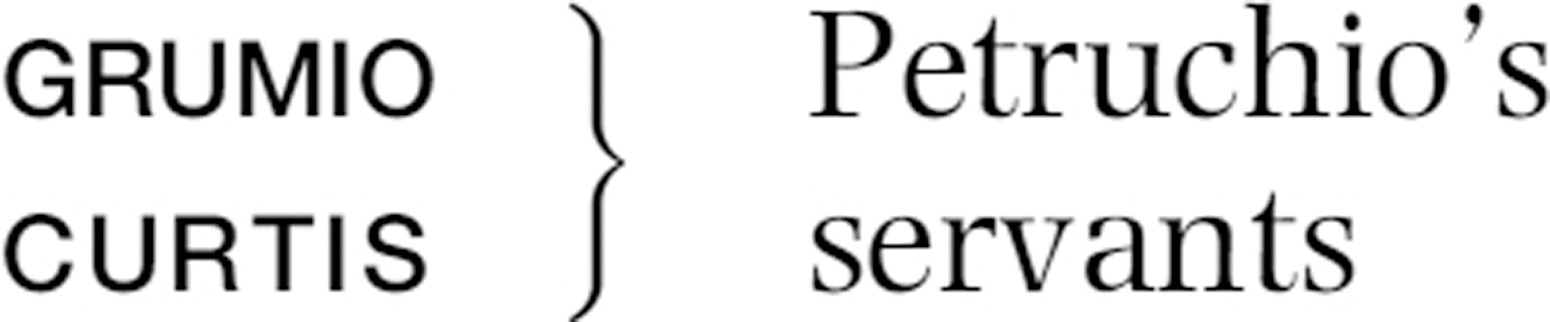

PLOT: Christopher Sly, a beggarly tinker, falls asleep drunk, having been thrown out of an ale-house. A lord takes him into his house and plays a trick involving the pretence that Sly is a lord himself, for whose benefit a company of players will act The Taming of the Shrew. The main action then commences. Fortune-hunting Hortensio, rich old Gremio, and newly-arrived-in-town Lucentio all wish to court beautiful Bianca, but she cannot marry before her older sister, shrewish Kate. Petruchio vows to woo Kate both for her dowry and for the challenge of overcoming her fearsome reputation. Hortensio and Lucentio gain access to Bianca by disguising themselves as tutors, while Lucentio’s servant Tranio plays the role of his master. Petruchio marries Kate—turning up late wearing the most unsuitable clothes imaginable—and takes her off to his country house, where he “tames” her through various forms of deprivation. Tranio persuades a traveling schoolteacher to pretend to be Lucentio’s father Vincentio in order to give assurance of Lucentio’s financial means; there is confusion when the real Vincentio turns up, but the love-match between Lucentio and Bianca is happily settled. Hortensio marries a wealthy widow and Petruchio and Kate return to reveal that she is a changed woman.

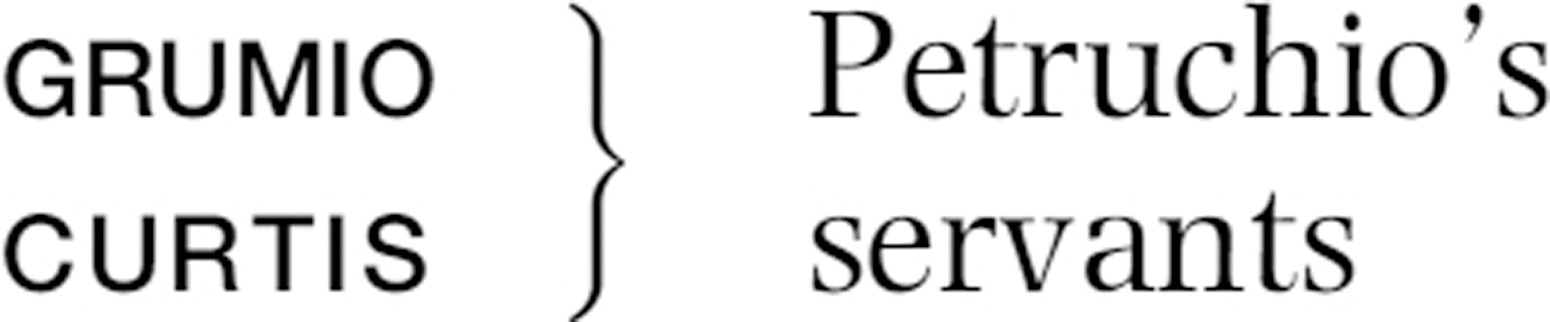

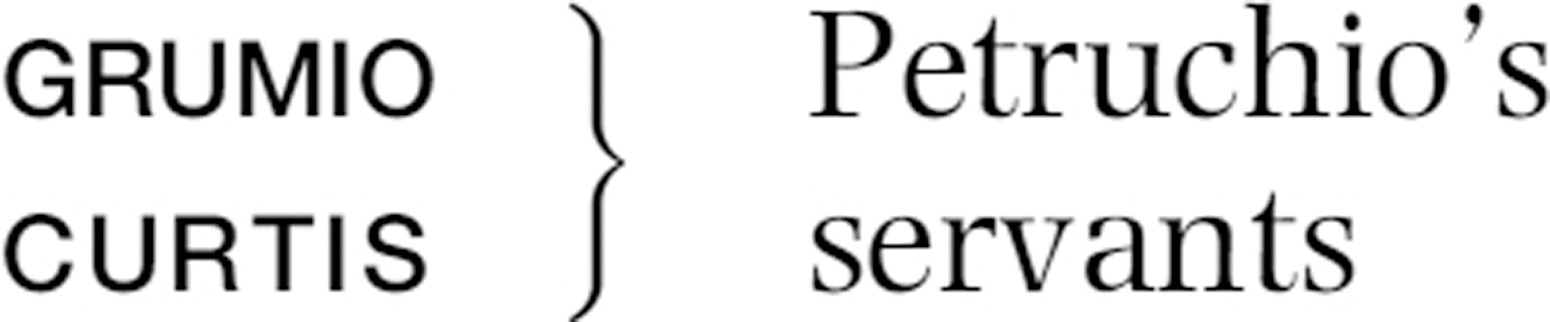

MAJOR PARTS: (with percentages of lines/number of speeches/scenes on stage) Petruchio (22%/158/8), Tranio (11%/90/8), Kate (8%/82/8), Hortensio (8%/70/8), Baptista (7%/68/6), Lucentio (7%/61/8), Grumio (6%/63/4), Gremio (6%/58/6), Lord (5%/17/2), Biondello (4%/39/7), Bianca (3%/29/7), Sly (2%/24/3), Vincentio (2%/23/3), Pedant (2%/20/3).

LINGUISTIC MEDIUM: 80% verse, 20% prose.

DATE: Usually considered to be one of Shakespeare’s earliest works. Assuming that Quarto The Taming of a Shrew, registered for publication May 1594, is a version of the text rather than a source for it (see below), the play is likely to pre-date the long periods of plague closure that inhibited theatrical activity from summer 1592 onward, but there is no firm evidence for a more precise date.

SOURCES: The Induction’s scenario of a beggar transported into luxury is a traditional motif in ballads and the folk tradition; the shrewish wife is also common in fabliaux and other forms of popular tale, as well as classical comedy; Socrates, wisest of the ancients, was supposed to be married to the shrewish Xanthippe; the courtship of Bianca is developed from George Gascoigne’s Supposes (1566), itself a prose translation of Ludovico Ariosto’s I Suppositi (1509), an archetypal Italian Renaissance comedy suffused with conventions derived from the ancient Roman comedies of Plautus and Terence. Some scholars suppose that The Taming of a Shrew (1594) is a badly printed text of an older play that was Shakespeare’s primary source, but others regard it as an adaptation of Shakespeare’s work; it includes the Christopher Sly frame, the taming of Kate (with a differently named tamer), and a highly variant version of the Bianca sub-plot.

TEXT: The 1623 Folio is the only authoritative text; it seems to have been set from manuscript copy, possibly a scribal transcript that retains some of the marks of Shakespeare’s working manuscript. The 1594 Quarto Taming of a Shrew must be regarded as an autonomous work, but it provides a source for emendations on a few occasions where it corresponds closely to The Shrew.

BAPTISTA Minola, a gentleman of Padua

KATE (Katherina), his elder daughter, the “shrew”

BIANCA, his younger daughter

PETRUCHIO, a gentleman from Verona, suitor to Kate

LUCENTIO, in love with Bianca (disguises himself as “Cambio,” a Latin tutor)

VINCENTIO, Lucentio’s father, a merchant from Pisa

GREMIO, an aged suitor to Bianca

HORTENSIO, friend of Petruchio and suitor to Bianca (disguises himself as “Litio,” a music tutor)

TRANIO, Lucentio’s servant

BIONDELLO, a boy in the service of Lucentio

A PEDANT

A WIDOW

A TAILOR

A HABERDASHER

Servants and Messengers (Petruchio has servants named NATHANIEL, JOSEPH, NICHOLAS, PHILIP and PETER)

running scene 1

Enter Beggar and Hostess, [the beggar is called] Christopher Sly

SLY

SLY I’ll pheeze

1 you, in faith.

HOSTESS

HOSTESS A

2 pair of stocks, you rogue!

SLY

SLY You’re a baggage,

3 the Slys are no rogues. Look in the chronicles, we came in with Richard Conqueror:

4 therefore

paucas pallabris, let the world slide. Sessa!

HOSTESS

HOSTESS You will not pay for the glasses you have burst?

5

SLY

SLY No, not a denier.

6 Go by, Saint Jeronimy, go to thy cold bed and warm thee.

HOSTESS

HOSTESS I know my remedy: I must go fetch the thirdborough.

7

[Exit]

SLY

SLY Third, or fourth, or fifth borough, I’ll answer him by law.

8 I’ll not budge an inch, boy. Let him come, and kindly.

9

[He] falls asleep

Wind horns. Enter a Lord from hunting, with his train

10

10

LORD

LORD Huntsman, I charge

10 thee tender well my hounds.

Brach11 Merriman, the poor cur is embossed,

And couple12 Clowder with the deep-mouthed brach.

Saw’st thou not, boy, how Silver made it good13

At the hedge-corner, in the coldest fault?14

15

15 I would not lose the dog for twenty pound.

FIRST HUNTSMAN

FIRST HUNTSMAN Why, Belman is as good as he, my lord.

He cried17 upon it at the merest loss,

And twice today picked out the dullest scent.

Trust me, I take him for the better dog.

20

20

LORD

LORD Thou art a fool. If Echo were as fleet,

20

I would esteem him worth a dozen such.

But sup22 them well and look unto them all:

Tomorrow I intend to hunt again.

FIRST HUNTSMAN

FIRST HUNTSMAN I will, my lord.

25

25

LORD

LORD What’s here? One dead, or drunk? See, doth he breathe?

Sees Sly

SECOND HUNTSMAN

SECOND HUNTSMAN He breathes, my lord. Were he not warmed with ale,

This were a bed but cold27 to sleep so soundly.

LORD

LORD O monstrous beast, how like a swine he lies!

Grim29 death, how foul and loathsome is thine image.

30

30 Sirs, I will practise on30 this drunken man.

What think you, if he were conveyed to bed,

Wrapped in sweet32 clothes, rings put upon his fingers,

A most delicious banquet33 by his bed,

And brave34 attendants near him when he wakes,

35

35 Would not the beggar then forget himself?35

FIRST HUNTSMAN

FIRST HUNTSMAN Believe me, lord, I think he cannot choose.

36

SECOND HUNTSMAN

SECOND HUNTSMAN It would seem strange

37 unto him when he waked.

LORD

LORD Even as a flatt’ring dream or worthless fancy.

38

Then take him up and manage well the jest:

40

40 Carry him gently to my fairest chamber

And hang it round41 with all my wanton pictures:

Balm42 his foul head in warm distillèd waters

And burn sweet43 wood to make the lodging sweet:

Procure me music ready when he wakes,

45

45 To make a dulcet45 and a heavenly sound.

And if he chance to speak, be ready straight46

And with a low47 submissive reverence

Say ‘What is it your honour will command?’

Let one attend him with a silver basin

50

50 Full of rose-water and bestrewed with flowers,

Another bear the ewer,51 the third a diaper,

And say ‘Will’t please your lordship cool your hands?’

Someone be ready with a costly suit

And ask him what apparel he will wear.

55

55 Another tell him of his hounds and horse,

And that his lady mourns at his disease.56

Persuade him that he hath been lunatic,

And when he says he is,58 say that he dreams,

For he is nothing but a mighty lord.

60

60 This do, and do it kindly,60 gentle sirs.

It will be pastime passing61 excellent,

If it be husbanded62 with modesty.

FIRST HUNTSMAN

FIRST HUNTSMAN My lord, I warrant

63 you we will play our part,

As64 he shall think by our true diligence

65

65 He is no less than what we say he is.

LORD

LORD Take him up gently and to bed with him,

Some carry out Sly

And each one to his office67 when he wakes

Sound trumpets

Sirrah,68 go see what trumpet ’tis that sounds.

[Exit a Servingman]

Belike,69 some noble gentleman that means,

70

70 Travelling some journey, to repose him here.

How now? Who is it?

SERVINGMAN

SERVINGMAN An’t

72 please your honour, players

That offer service to your lordship.

Enter Players

LORD

LORD Bid them come near.— Now, fellows, you are welcome.

75

75

PLAYERS

PLAYERS We thank your honour.

LORD

LORD Do you intend to stay with me tonight?

SECOND PLAYER

SECOND PLAYER So please

77 your lordship to accept our duty.

LORD

LORD With all my heart. This fellow I remember,

Since once he played a farmer’s eldest son.

80

80 ’Twas where you wooed the gentlewoman so well:

I have forgot your name, but, sure, that part

Was aptly fitted82 and naturally performed.

FIRST PLAYER

FIRST PLAYER I think ’twas Soto that your honour means.

LORD

LORD ’Tis very true, thou didst it excellent.

85

85 Well, you are come to me in happy85 time,

The rather for86 I have some sport in hand

Wherein your cunning87 can assist me much.

There is a lord will hear you play tonight;

But I am doubtful89 of your modesties,

90

90 Lest over-eyeing of90 his odd behaviour —

For yet his honour never heard a play —

You break into some merry passion92

And so offend him, for I tell you, sirs,

If you should smile he grows impatient.94

95

95

FIRST PLAYER

FIRST PLAYER Fear not, my lord, we can contain ourselves

Were he the veriest antic96 in the world.

LORD

LORD Go, sirrah, take them to the buttery,

97 To a Servingman

And give them friendly welcome every one.

Let them want99 nothing that my house affords.

Exit one with the Players

100

100 Sirrah, go you to Barthol’mew my page,

And see him dressed in all suits101 like a lady.

That done, conduct him to the drunkard’s chamber,

And call him ‘madam’, do him obeisance.103

Tell him from me, as he will104 win my love,

105

105 He bear105 himself with honourable action,

Such as he hath observed in noble ladies

Unto their lords, by them accomplishèd:107

Such duty108 to the drunkard let him do

With soft low tongue109 and lowly courtesy,

110

110 And say, ‘What is’t your honour will command,

Wherein your lady and your humble wife

May show her duty and make known her love?’

And then with kind embracements, tempting kisses,

And with114 declining head into his bosom,

115

115 Bid him shed tears, as being overjoyed

To see her noble lord restored to health,

Who for this seven years hath esteemèd him117

No better than a poor and loathsome beggar:

And if the boy have not a woman’s gift

120

120 To rain a shower of commanded tears,120

An onion will do well for such a shift,121

Which in a napkin122 being close conveyed

Shall in despite123 enforce a watery eye.

See this dispatched124 with all the haste thou canst.

125

125 Anon125 I’ll give thee more instructions.

Exit a Servingman

I know the boy will well usurp the grace,126

Voice, gait and action of a gentlewoman:

I long to hear him call the drunkard husband,

And how129 my men will stay themselves from laughter

130

130 When they do homage to this simple peasant.

I’ll in131 to counsel them. Haply my presence

May well abate the over-merry spleen132

Which otherwise would grow into extremes.

[Exeunt]

running scene 1 continues

Enter aloft the drunkard [Sly] with Attendants, some with apparel, basin and ewer, and other appurtenances, and Lord

SLY

SLY For God’s sake, a pot of small

1 ale.

FIRST SERVINGMAN

FIRST SERVINGMAN Will’t please your lordship drink a cup of sack?

SECOND SERVINGMAN

SECOND SERVINGMAN Will’t please your honour taste of these conserves?

3

THIRD SERVINGMAN

THIRD SERVINGMAN What raiment

4 will your honour wear today?

SLY

SLY I am Christophero Sly, call not me ‘honour’ nor ‘lordship’. I ne’er drank sack in my life: and if you give me any conserves, give me conserves of beef:

6 ne’er ask me what raiment I’ll wear, for I have no more doublets

7 than backs, no more stockings than legs, nor no more shoes than feet — nay, sometime more feet than shoes, or such shoes as my toes look

9 through the over-leather.

10

10

LORD

LORD Heaven cease this idle humour

10 in your honour!

O, that a mighty man of such descent,

Of such possessions and so high esteem,

Should be infusèd with so foul a spirit!13

SLY

SLY What, would you make me mad? Am not I Christopher Sly, old Sly’s son of Burtonheath,

15 by birth a pedlar, by education a cardmaker, by transmutation a bear-herd,

16 and now by present profession a tinker? Ask Marian Hacket, the fat ale-wife

17 of Wincot, if she know me not: if she say I am not fourteen pence on the score

18 for sheer ale, score me up for the lying’st knave in Christendom. What, I am not bestraught!

19 Here’s—

20

20

THIRD SERVINGMAN

THIRD SERVINGMAN O, this it is that makes your lady mourn!

SECOND SERVINGMAN

SECOND SERVINGMAN O, this is it that makes your servants droop!

21

LORD

LORD Hence comes it that your kindred shuns your house,

As23 beaten hence by your strange lunacy.

O noble lord, bethink thee of thy birth,

25

25 Call home thy ancient25 thoughts from banishment

And banish hence these abject lowly dreams.26

Look how thy servants do attend on thee,

Each in his office ready at thy beck.

Wilt thou have music? Hark! Apollo29 plays,

Music

30

30 And twenty cagèd nightingales do sing.

Or wilt thou sleep? We’ll have thee to a couch

Softer and sweeter than the lustful32 bed

On purpose trimmed up33 for Semiramis.

Say thou wilt walk, we will bestrow34 the ground.

35

35 Or wilt thou ride? Thy horses shall be trapped,35

Their harness studded all with gold and pearl.

Dost thou love hawking?37 Thou hast hawks will soar

Above the morning lark. Or wilt thou hunt?

Thy hounds shall make the welkin39 answer them

40

40 And fetch shrill echoes from the hollow earth.

FIRST SERVINGMAN

FIRST SERVINGMAN Say thou wilt course,

41 thy greyhounds are as swift

As breathèd42 stags, ay, fleeter than the roe.

SECOND SERVINGMAN

SECOND SERVINGMAN Dost thou love pictures? We will fetch thee straight

Adonis44 painted by a running brook,

45

45 And Cytherea45 all in sedges hid,

Which seem to move and wanton46 with her breath,

Even as the waving sedges play with wind.

LORD

LORD we’ll show thee Io

48 as she was a maid,

And how she was beguilèd49 and surprised,

50

50 As lively50 painted as the deed was done.

THIRD SERVINGMAN

THIRD SERVINGMAN Or Daphne

51 roaming through a thorny wood,

Scratching her legs that one shall swear she bleeds,

And at that sight shall sad Apollo weep,

So workmanly54 the blood and tears are drawn.

55

55

LORD

LORD Thou art a lord, and nothing but a lord.

Thou hast a lady far more beautiful

Than any woman in this waning57 age.

FIRST SERVINGMAN

FIRST SERVINGMAN And till the tears that she hath shed for thee

Like envious59 floods o’errun her lovely face,

60

60 She was the fairest creature in the world,

And yet61 she is inferior to none.

SLY

SLY Am I a lord? And have I such a lady?

Or do I dream? Or have I dreamed till now?

I do not sleep: I see, I hear, I speak,

65

65 I smell sweet savours and I feel soft things.

Upon my life, I am a lord indeed

And not a tinker nor Christopher SIy.

Well, bring our lady hither to our sight,

And once again, a pot o’th’smallest ale.

70

70

SECOND SERVINGMAN

SECOND SERVINGMAN Will’t please your mightiness to wash your hands?

O, how we joy to see your wit71 restored!

O, that once more you knew but72 what you are!

These fifteen years you have been in a dream,

Or when you waked, so waked as if you slept.

75

75

SLY

SLY These fifteen years! By my fay,

75 a goodly nap.

But did I never speak of76 all that time?

FIRST SERVINGMAN

FIRST SERVINGMAN O, yes, my lord, but very idle words,

For though you lay here in this goodly chamber,

Yet would you say ye were beaten out of door,

80

80 And rail upon80 the hostess of the house,

And say you would present81 her at the leet,

Because she brought stone82 jugs and no sealed quarts:

Sometimes you would call out for Cicely Hacket.

SLY

SLY Ay, the woman’s

84 maid of the house.

85

85

THIRD SERVINGMAN

THIRD SERVINGMAN Why, sir, you know no house nor no such maid,

Nor no such men as you have reckoned up,86

As Stephen Sly and old John Naps of Greece87

And Peter Turph and Henry Pimpernell

And twenty more such names and men as these

90

90 Which never were nor no man ever saw.

SLY

SLY Now lord be thankèd for my good amends!

91

Enter [the Page dressed as a] lady, with Attendants

SLY

SLY I thank thee. Thou shalt not lose by it.

PAGE

PAGE How fares my noble lord?

95

95

SLY

SLY Marry,

95 I fare well, for here is cheer enough. Where is my wife?

PAGE

PAGE Here, noble lord. What is thy will with her?

SLY

SLY Are you my wife and will not call me husband?

My men should call me ‘lord’. I am your Goodman.98

PAGE

PAGE My husband and my lord, my lord and husband,

100

100 I am your wife in all obedience.

SLY

SLY I know it well.— What must I call her?

SLY

SLY Al’ce

103 madam, or Joan madam?

LORD

LORD ‘Madam’, and nothing else. So lords call ladies.

105

105

SLY

SLY Madam wife, they say that I have dreamed

And slept above some fifteen year or more.

PAGE

PAGE Ay, and the time seems thirty unto me,

Being all this time abandoned108 from your bed.

SLY

SLY ’Tis much. Servants, leave me and her alone.

[Exeunt Attendants]

110

110 Madam, undress you and come now to bed.

PAGE

PAGE Thrice-noble lord, let me entreat of you

To pardon me yet for a night or two,

Or, if not so, until the sun be set.

For your physicians have expressly charged,

115

115 In115 peril to incur your former malady,

That I should yet absent me from your bed:

I hope this reason stands for117 my excuse.

SLY

SLY Ay, it stands

118 so that I may hardly tarry so long. But I would be loath to fall into my dreams again. I will therefore tarry in despite

119 of the flesh and the blood.

Enter a Messenger

120

120

MESSENGER

MESSENGER Your honour’s players, hearing your amendment,

Are come to play a pleasant121 comedy,

For so your doctors hold it very meet,122

Seeing too much sadness hath congealed your blood,

And melancholy is the nurse of frenzy:

125

125 Therefore they thought it good you hear a play

And frame126 your mind to mirth and merriment,

Which bars127 a thousand harms and lengthens life.

SLY

SLY Marry, I will, let them play it. Is not a comonty

128 a Christmas gambold or a tumbling trick?

PAGE

PAGE No, my good lord, it is more pleasing stuff.

130

SLY

SLY What, household stuff?

PAGE

PAGE It is a kind of history.

132

SLY

SLY Well, we’ll see’t. Come, madam wife, sit by my side and let the world slip,

133 They sit we shall ne’er be younger.

Flourish

running scene 2

Enter Lucentio and his man Tranio

LUCENTIO

LUCENTIO Tranio, since for the great desire I had

To see fair Padua,2 nursery of arts,

I am arrived for3 fruitful Lombardy,

The pleasant garden of great Italy,

5

5 And by my father’s love and leave5 am armed

With his good will and thy good company,

My trusty servant, well approved7 in all,

Here let us breathe8 and haply institute

A course of learning and ingenious9 studies.

10

10 Pisa, renownèd for grave10 citizens,

Gave11 me my being and my father first,

A merchant of great traffic12 through the world,

Vincentio come of13 the Bentivolii.

Vincentio’s14 son, brought up in Florence,

15

15 It shall become to serve all hopes conceived,

To deck his fortune with his virtuous deeds:

And therefore, Tranio, for the time I study,

Virtue and that part of philosophy

Will I apply that treats of19 happiness

20

20 By virtue specially to be achieved.

Tell me thy mind, for I have Pisa left

And am to Padua come, as he that leaves

A shallow plash23 to plunge him in the deep

And with satiety24 seeks to quench his thirst.

25

25

TRANIO

TRANIO Mi perdonato,

25 gentle master mine.

I am in all affected26 as yourself,

Glad that you thus continue your resolve

To suck the sweets of sweet philosophy.

Only, good master, while we do admire

30

30 This virtue and this moral discipline,

Let’s be no stoics31 nor no stocks, I pray,

Or so devote to Aristotle’s32 checks

As33 Ovid be an outcast quite abjured.

Balk34 logic with acquaintance that you have

35

35 And practise rhetoric in your common35 talk,

Music and poesy use to quicken36 you;

The mathematics and the metaphysics,

Fall to38 them as you find your stomach serves you.

No39 profit grows where is no pleasure ta’en:

40

40 In brief, sir, study what you most affect.40

LUCENTIO

LUCENTIO Gramercies,

41 Tranio, well dost thou advise.

If, Biondello, thou wert42 come ashore,

We could at once put us in readiness,

And take a lodging fit to entertain

45

45 Such friends as time in Padua shall beget.45

But stay a while, what company is this?

TRANIO

TRANIO Master, some show to welcome us to town.

Enter Baptista with his two daughters, Katherina and Bianca, Gremio a pantaloon, Hortensio suitor to Bianca. Lucentio [and] Tranio stand by

BAPTISTA

BAPTISTA Gentlemen, importune

48 me no farther,

For how I firmly am resolved you know:

50

50 That is, not to bestow50 my youngest daughter

Before I have a husband for the elder.

If either of you both love Katherina,

Because I know you well and love you well,

Leave shall you have to court her at your pleasure.

55

55

GREMIO

GREMIO To cart her

55 rather. She’s too rough for me.

Aside?

There, there, Hortensio, will you56 any wife?

KATE

KATE I pray you, sir, is it your will

To Baptista

To make a stale58 of me amongst these mates?

HORTENSIO

HORTENSIO Mates’, maid? How mean you that? No mates for you,

60

60 Unless you were of gentler, milder mould.

KATE

KATE I’faith, sir, you shall never need to fear:

Iwis62 it is not halfway to her heart.

But if it were, doubt not her care63 should be

To comb your noddle64 with a three-legged stool

65

65 And paint65 your face and use you like a fool.

HORTENSIO

HORTENSIO From all such devils, good lord deliver us!

GREMIO

GREMIO And me too, good lord!

TRANIO

TRANIO Husht, master! Here’s some good pastime toward;

68 Aside to Lucentio

That wench is stark mad or wonderful froward.69

70

70

LUCENTIO

LUCENTIO But in the other’s silence do I see

Aside to Tranio

Maid’s mild behaviour and sobriety.

Peace, Tranio!

TRANIO

TRANIO Well said, master. Mum,

73 and gaze your fill.

Aside to Lucentio

BAPTISTA

BAPTISTA Gentlemen, that I may soon make good

75

75 What I have said, Bianca, get you in,

And let it not displease thee, good Bianca,

For I will love thee ne’er the less, my girl.

KATE

KATE A pretty peat!

78 It is best

Put79 finger in the eye, an she knew why.

80

80

BIANCA

BIANCA Sister, content you

80 in my discontent.

Sir, to your pleasure81 humbly I subscribe:

My books and instruments shall be my company,

On them to look and practise by myself.

LUCENTIO

LUCENTIO Hark, Tranio, thou may’st hear Minerva

84 speak.

85

HORTENSIO

HORTENSIO Signior Baptista, will you be so strange?

85

Sorry am I that our good will effects86

Bianca’s grief.

GREMIO

GREMIO Why will you mew her up,

88

Signior Baptista, for89 this fiend of hell,

90

90 And make her90 bear the penance of her tongue?

BAPTISTA

BAPTISTA Gentlemen, content ye, I am resolved.—

Go in, Bianca.—

[Exit Bianca]

And for93 I know she taketh most delight

In music, instruments and poetry,

95

95 Schoolmasters will I keep within my house

Fit to instruct her youth. If you, Hortensio,

Or Signior Gremio, you, know any such,

Prefer98 them hither, for to cunning men

I will be very kind, and liberal

100

100 To mine own children in good bringing up.

And so farewell.— Katherina, you may stay,

For I have more to commune102 with Bianca.

Exit

KATE

KATE Why, and I trust I may go too, may I not? What, shall I be appointed hours,

103 as though, belike,

104 I knew not what to take and what to leave? Ha?

Exit

GREMIO

GREMIO You may go to the devil’s dam.

105 Your gifts are so good, here’s none will hold you.— Their love

106 is not so great, Hortensio, but we may blow our nails together, and fast

107 it fairly out. Our cake’s dough on both sides. Farewell. Yet for the love I bear my sweet Bianca, if I can by any means light on

108 a fit man to teach her that wherein she delights, I will wish

109 him to her father.

HORTENSIO

HORTENSIO So will I, Signior Gremio. But a word, I pray. Though the nature of our quarrel yet never brooked parle,

111 know now, upon advice, it toucheth us both — that we may yet again have access to our fair mistress and be happy rivals in Bianca’s love — to labour and effect

113 one thing specially.

GREMIO

GREMIO What’s that, I pray?

HORTENSIO

HORTENSIO Marry, sir, to get a husband for her sister.

GREMIO

GREMIO A husband? A devil.

HORTENSIO

HORTENSIO I say a husband.

GREMIO

GREMIO I say a devil. Think’st thou, Hortensio, though her father be very rich, any man is so very a fool to be married to hell?

HORTENSIO

HORTENSIO Tush, Gremio, though it pass

120 your patience and mine to endure her loud alarums,

121 why, man, there be good fellows in the world, an a man could light on them, would take her with all faults, and money enough.

GREMIO

GREMIO I cannot tell, but I had as lief

123 take her dowry with this condition: to be whipped at the high cross

124 every morning.

HORTENSIO

HORTENSIO Faith, as you say, there’s small choice in rotten apples. But come, since this bar in law

126 makes us friends, it shall be so far forth friendly maintained till by helping Baptista’s eldest daughter to a husband we set his youngest free for a husband, and then have

128 to’t afresh. Sweet Bianca! Happy man be his dole! He that runs fastest gets the ring.

129 How say you, Signior Gremio?

GREMIO

GREMIO I am agreed, and would I had given him the best horse in Padua to begin his wooing that would thoroughly woo her, wed her and bed her and rid the house of her! Come on.

Exeunt both [

Gremio and Hortensio].

Tranio and Lucentio remain

TRANIO

TRANIO I pray, sir, tell me, is it possible

That love should of a sudden take such hold?

135

135

LUCENTIO

LUCENTIO O Tranio, till I found it to be true,

I never thought it possible or likely.

But see, while idly I stood looking on,

I found the effect of love in idleness,138

And now in plainness do confess to thee,

140

140 That art to me as secret140 and as dear

As Anna141 to the Queen of Carthage was,

Tranio, I burn, I pine, I perish, Tranio,

If I achieve not this young modest girl.

Counsel me, Tranio, for I know thou canst.

145

145 Assist me, Tranio, for I know thou wilt.

TRANIO

TRANIO Master, it is no time to chide you now.

Affection is not rated147 from the heart:

If love have touched you, naught remains but so,

Redime149 te captum quam queas minimo.

150

150

LUCENTIO

LUCENTIO Gramercies, lad. Go forward.

150 This contents:

The rest will comfort, for thy counsel’s sound.

TRANIO

TRANIO Master, you looked so longly

152 on the maid,

Perhaps you marked not153 what’s the pith of all.

LUCENTIO

LUCENTIO O, yes, I saw sweet beauty in her face,

155

155 Such as the daughter of Agenor155 had,

That made great Jove to humble him156 to her hand.

When with his knees he kissed157 the Cretan strand.

TRANIO

TRANIO Saw you no more? Marked you not how her sister

Began to scold and raise up such a storm

160

160 That mortal ears might hardly endure the din?

LUCENTIO

LUCENTIO Tranio, I saw her coral lips to move

And with her breath she did perfume the air.

Sacred and sweet was all I saw in her.

TRANIO

TRANIO Nay, then, ’tis time to stir him from his trance.—

Aside

165

165 I pray, awake, sir. If you love the maid,

Bend166 thoughts and wits to achieve her. Thus it stands:

Her elder sister is so curst167 and shrewd

That till the father rid his hands of her,

Master, your love must live a maid169 at home,

170

170 And therefore has he closely170 mewed her up,

Because she will not be annoyed171 with suitors.

LUCENTIO

LUCENTIO Ah, Tranio, what a cruel father’s he!

But art thou not advised173 he took some care

To get her cunning schoolmasters to instruct her?

175

175

TRANIO

TRANIO Ay, marry, am I, sir, and now ’tis plotted.

LUCENTIO

LUCENTIO I have it, Tranio.

TRANIO

TRANIO Master, for my hand,

177

Both our inventions meet178 and jump in one.

LUCENTIO

LUCENTIO Tell me thine first.

180

TRANIO

TRANIO You will be schoolmaster

And undertake the teaching of the maid:

That’s your device.182

LUCENTIO

LUCENTIO It is: may it be done?

TRANIO

TRANIO Not possible, for who shall bear

184 your part,

185

185 And be in Padua here Vincentio’s son,

Keep house186 and ply his book, welcome his friends,

Visit his countrymen and banquet them?

LUCENTIO

LUCENTIO Basta,

188 content thee, for I have it full.

We have not yet been seen in any house,

190

190 Nor can we be distinguished by our faces

For man or master. Then it follows thus:

Thou shalt be master, Tranio, in my stead,

Keep house and port193 and servants as I should.

I will some other be, some Florentine,

195

195 Some Neapolitan, or meaner195 man of Pisa.

’Tis hatched and shall be so. Tranio, at once

Uncase197 thee: take my coloured hat and cloak. They exchange clothes

When Biondello comes, he waits on thee,

But I will charm199 him first to keep his tongue.

200

200

TRANIO

TRANIO So had you need.

In brief, sir, sith201 it your pleasure is,

And I am tied202 to be obedient —

For so your father charged203 me at our parting,

‘Be serviceable to my son’, quoth he,

205

205 Although I think ’twas in another sense —

I am content to be Lucentio,

Because so well I love Lucentio.

LUCENTIO

LUCENTIO Tranio, be so, because Lucentio loves.

And let me be a slave, t’achieve that maid

210

210 Whose sudden sight210 hath thralled my wounded eye.

Enter Biondello

Here comes the rogue. Sirrah, where have you been?

BIONDELLO

BIONDELLO Where have I been? Nay, how now? Where are you? Master, has my fellow Tranio stolen your clothes? Or you stolen his? Or both? Pray, what’s the news?

215

215

LUCENTIO

LUCENTIO Sirrah, come hither. ’Tis no time to jest,

And therefore frame216 your manners to the time.

Your fellow Tranio here, to save my life,

Puts my apparel and my count’nance218 on,

And I for my escape have put on his,

220

220 For in a quarrel since I came ashore

I killed a man, and fear I was descried.221

Wait you on him, I charge you, as becomes,222

While I make way from hence to save my life.

You understand me?

225

225

BIONDELLO

BIONDELLO I, sir? Ne’er a whit.

LUCENTIO

LUCENTIO And not a jot of Tranio in your mouth.

Tranio is changed into Lucentio.

BIONDELLO

BIONDELLO The better for him. Would I were so too!

TRANIO

TRANIO So could I, faith, boy, to have the next wish after,

230

230 That Lucentio indeed had Baptista’s youngest daughter.

But, sirrah, not for my sake, but your master’s, I advise

You use your manners discreetly232 in all kind of companies:

When I am alone, why, then I am Tranio,

But in all places else your master Lucentio.

LUCENTIO

LUCENTIO Tranio, let’s go. One thing more rests

235 that thyself execute: to make one among these wooers. If thou ask me why, sufficeth

236 my reasons are both good and weighty.

Exeunt

The Presenters above speaks

FIRST SERVINGMAN

FIRST SERVINGMAN My lord, you nod. You do not mind

238 the play.

SLY

SLY Yes, by Saint Anne, do I. A good matter,

239 surely.

240

240 Comes there any more of it?

PAGE

PAGE My lord, ’tis but begun.

SLY

SLY ’Tis a very excellent piece of work, madam lady.

Would243 ’twere done!

They sit and mark

running scene 2 continues

Enter Petruchio and his man Grumio

PETRUCHIO

PETRUCHIO Verona,

1 for a while I take my leave,

To see my friends in Padua; but of all2

My best belovèd and approvèd friend,

Hortensio, and I trow4 this is his house.

5

5 Here, sirrah Grumio, knock, I say.

GRUMIO

GRUMIO Knock,

6 sir? Whom should I knock? Is there any man has rebused your worship?

PETRUCHIO

PETRUCHIO Villain, I say, knock me here soundly.

GRUMIO

GRUMIO Knock you here, sir? Why, sir, what am I, sir, that I should knock you here, sir?

PETRUCHIO

PETRUCHIO Villain,

11 I say, knock me at this gate

And rap me well, or I’ll knock your knave’s pate.12

GRUMIO

GRUMIO My master is grown quarrelsome. I

13 should knock you first,

And then I know after who comes by the worst.

15

15

PETRUCHIO

PETRUCHIO Will it not be?

Faith, sirrah, an you’ll not knock, I’ll ring16 it.

I’ll17 try how you can sol-fa and sing it.

He wrings him by the ears

GRUMIO

GRUMIO Help, mistress,

18 help! My master is mad.

PETRUCHIO

PETRUCHIO Now, knock when I bid you, sirrah villain.

Enter Hortensio

HORTENSIO

HORTENSIO How now? What’s the matter? My old friend Grumio and my good friend Petruchio? How

21 do you all at Verona?

PETRUCHIO

PETRUCHIO Signior Hortensio, come you to part the fray?

Con23 tutto il cuore, ben trovato, may I say.

HORTENSIO

HORTENSIO Alla24 nostra casa ben venuto,

molto honorata signor mio Petruchio. Rise, Grumio, rise. We will compound

25 this quarrel.

GRUMIO

GRUMIO Nay, ’tis no matter, sir, what he ’leges

26 in Latin. If this be not a lawful cause for me to leave his service, look you, sir: he bid me knock him and rap him soundly, sir. Well, was it fit for a servant to use

28 his master so, being perhaps, for aught

29 I see, two and thirty, a pip out?

30

30 Whom would to God I had well knocked at first,

Then had not Grumio come by the worst.

PETRUCHIO

PETRUCHIO A senseless villain! Good Hortensio,

I bade the rascal knock upon your gate

And could not get him for my heart34 to do it.

GRUMIO

GRUMIO Knock at the gate? O heavens! Spake you not these words plain, ‘Sirrah, knock me here, rap me here, knock me well, and knock me soundly’? And come you now with, ‘knocking at the gate’?

PETRUCHIO

PETRUCHIO Sirrah, be gone, or talk not, I advise you.

HORTENSIO

HORTENSIO Petruchio, patience. I am Grumio’s pledge.

39

40

40 Why, this’40 a heavy chance ’twixt him and you,

Your ancient,41 trusty, pleasant servant Grumio.

And tell me now, sweet friend, what happy42 gale

Blows you to Padua here from old Verona?

PETRUCHIO

PETRUCHIO Such wind as scatters young men through the world,

45

45 To seek their fortunes further than at home

Where small experience grows. But in a few,46

Signior Hortensio, thus it stands with me:

Antonio, my father, is deceased,

And I have thrust myself into this maze,

50

50 Happily to wive50 and thrive as best I may.

Crowns51 in my purse I have and goods at home,

And so am come abroad to see the world.

HORTENSIO

HORTENSIO Petruchio, shall I then come roundly

53 to thee

And wish54 thee to a shrewd ill-favoured wife?

55

55 Thou’ldst55 thank me but a little for my counsel.

And yet I’ll promise thee she shall be rich,

And very rich. But thou’rt too much my friend,

And I’ll not wish thee to her.

PETRUCHIO

PETRUCHIO Signior Hortensio, ’twixt such friends as we

60

60 Few words suffice: and therefore, if thou know

One rich enough to be Petruchio’s wife —

As wealth is burden62 of my wooing dance —

Be she as foul as was Florentius’ love,63

As old as Sibyl64 and as curst and shrewd

65

65 As Socrates’ Xanthippe,65 or a worse,

She moves me not,66 or not removes, at least,

Affection’s edge in me, were she as rough

As are the swelling Adriatic seas.

I come to wive it wealthily in Padua,

70

70 If wealthily, then happily in Padua.

GRUMIO

GRUMIO Nay, look you, sir, he tells you flatly what his mind

71 is. Why, give him gold enough and marry him to a puppet or an aglet-baby;

72 or an old trot with ne’er a tooth in her head, though she have as many diseases as two and fifty horses. Why, nothing comes amiss, so

74 money comes withal.

75

75

HORTENSIO

HORTENSIO Petruchio, since we are

75 stepped thus far in,

I will continue that I broached76 in jest.

I can, Petruchio, help thee to a wife

With wealth enough and young and beauteous,

Brought up as best becomes a gentlewoman.

80

80 Her only fault, and that is faults enough,

Is that she is intolerable81 curst

And shrewd and froward, so beyond all measure

That, were my state83 far worser than it is,

I would not wed her for a mine of gold.

85

85

PETRUCHIO

PETRUCHIO Hortensio, peace! Thou know’st not gold’s effect.

Tell me her father’s name and ’tis enough,

For I will board87 her, though she chide as loud

As thunder when the clouds in autumn crack.88

HORTENSIO

HORTENSIO Her father is Baptista Minola,

90

90 An affable and courteous gentleman.

Her name is Katherina Minola,

Renowned in Padua for her scolding tongue.

PETRUCHIO

PETRUCHIO I know her father, though I know not her,

And he knew my deceasèd father well.

95

95 I will not sleep, Hortensio, till I see her,

And therefore let me be thus bold with you

To give you over97 at this first encounter,

Unless you will accompany me thither.

GRUMIO

GRUMIO I pray you, sir, let him go while the humour

99 lasts. O’ my word, an she knew him as well as I do, she would think scolding would do little good upon him. She may perhaps call him half a score

101 knaves or so. Why, that’s nothing; an he begin once, he’ll rail

102 in his rope-tricks. I’ll tell you what, sir, an she stand him but a little, he will throw a figure

103 in her face and so disfigure her with it that she shall have no more eyes to see withal

104 than a cat. You know him not, sir.

105

105

HORTENSIO

HORTENSIO Tarry, Petruchio, I must go with thee,

For in Baptista’s keep106 my treasure is:

He hath the jewel of my life in hold,107

His youngest daughter, beautiful Bianca,

And her withholds from me and other more,109

110

110 Suitors to her and rivals in my love,

Supposing it a thing impossible,

For those defects112 I have before rehearsed,

That ever Katherina will be wooed:

Therefore this order114 hath Baptista ta’en,

115

115 That none shall have access unto Bianca

Till Katherine the curst have got a husband.

GRUMIO

GRUMIO Katherine the curst!

A title for a maid of all titles the worst.

HORTENSIO

HORTENSIO Now shall my friend Petruchio do me grace,

119

120

120 And offer me disguised in sober robes

To old Baptista as a schoolmaster

Well seen122 in music, to instruct Bianca,

That so I may by this device at least

Have leave and leisure to make love to124 her

125

125 And unsuspected court her by herself.

Enter Gremio and Lucentio disguised

GRUMIO

GRUMIO Here’s no knavery!

126 See, to beguile the old folks, how the young folks lay their heads together! Master, master, look about you. Who goes there, ha?

HORTENSIO

HORTENSIO Peace, Grumio, it is the rival of my love.

Petruchio, stand by a while. They stand aside

130

130

GRUMIO

GRUMIO A proper stripling

130 and an amorous!

Aside

GREMIO

GREMIO O, very well, I have perused the note.

131 To Lucentio

Hark you, sir, I’ll have them very fairly132 bound —

All books of love, see that at any hand133 —

And see you read134 no other lectures to her.

135

135 You understand me. Over and beside

Signior Baptista’s liberality,136

I’ll mend137 it with a largesse. Take your paper too, Gives Lucentio the note

And let me have them138 very well perfumed,

For she is sweeter than perfume itself

140

140 To whom they go to. What will you read to her?

LUCENTIO

LUCENTIO Whate’er I read to her, I’ll plead for you

As for my patron, stand you so assured,

As firmly as yourself143 were still in place —

Yea, and perhaps with more successful words

145

145 Than you, unless you were a scholar, sir.

GREMIO

GREMIO O, this learning, what a thing it is!

GRUMIO

GRUMIO O, this woodcock,

147 what an ass it is!

Aside

PETRUCHIO

PETRUCHIO Peace, sirrah!

HORTENSIO

HORTENSIO Grumio, mum.— God save you, Signior Gremio.

150

150

GREMIO

GREMIO And you

150 are well met, Signior Hortensio.

Trow you151 whither I am going? To Baptista Minola.

I promised to inquire carefully

About a schoolmaster for the fair Bianca,

And by good fortune I have lighted well

155

155 On this young man, for learning and behaviour

Fit156 for her turn, well read in poetry

And other books, good ones, I warrant ye.

HORTENSIO

HORTENSIO ’Tis well. And I have met a gentleman

Hath promised me to help me to159 another,

160

160 A fine musician to instruct our mistress.

So shall I no whit be behind in duty

To fair Bianca, so beloved of me.

GREMIO

GREMIO Beloved of me, and that my deeds shall prove.

GRUMIO

GRUMIO And that his bags

164 shall prove.

Aside

165

165

HORTENSIO

HORTENSIO Gremio, ’tis now no time to vent

165 our love.

Listen to me, and if you speak me fair,166

I’ll tell you news indifferent167 good for either.

Here is a gentleman whom by chance I met,

Upon agreement169 from us to his liking,

170

170 Will undertake to woo curst Katherine,

Yea, and to marry her, if her dowry please.

GREMIO

GREMIO So

172 said, so done, is well.

Hortensio, have you told him all her faults?

PETRUCHIO

PETRUCHIO I know she is an irksome brawling scold:

175

175 If that be all, masters, I hear no harm.

GREMIO

GREMIO No, say’st me so, friend? What countryman?

176

PETRUCHIO

PETRUCHIO Born in Verona, old Antonio’s son.

My father dead, my fortune lives for me,

And I do hope good days and long to see.

180

180

GREMIO

GREMIO O sir, such a life with such a wife were strange.

But if you have a stomach,181 to’t a’ God’s name.

You shall have me assisting you in all.

But will you woo this wild-cat?

PETRUCHIO

PETRUCHIO Will I live?

184

185

185

GRUMIO

GRUMIO Will he woo her? Ay, or I’ll hang her.

Aside?

PETRUCHIO

PETRUCHIO Why came I hither but to that intent?

Think you a little din can daunt mine ears?

Have I not in my time heard lions roar?

Have I not heard the sea, puffed up with winds,

190

190 Rage like an angry boar chafèd190 with sweat?

Have I not heard great ordnance191 in the field,

And heaven’s artillery thunder in the skies?

Have I not in a pitchèd193 battle heard

Loud ’larums,194 neighing steeds, and trumpets’ clang?

195

195 And do you tell me of a woman’s tongue,

That gives not half so great a blow to hear

As will a chestnut197 in a farmer’s fire?

Tush, tush! Fear198 boys with bugs.

GRUMIO

GRUMIO For he fears none.

200

200

GREMIO

GREMIO Hortensio, hark:

This gentleman is happily arrived,

My mind presumes, for his own good and yours.

HORTENSIO

HORTENSIO I promised we would be contributors

And bear his charge204 of wooing whatsoe’er.

205

205

GREMIO

GREMIO And so we will, provided that he win her.

GRUMIO

GRUMIO I would I were as sure of a good dinner.

Enter Tranio brave [disguised as Lucentio] and Biondello

TRANIO

TRANIO Gentlemen, God save you. If I may be bold,

Tell me, I beseech you, which is the readiest208 way

To the house of Signior Baptista Minola?

210

210

BIONDELLO

BIONDELLO He that has the two fair daughters, is’t he you mean?

TRANIO

TRANIO Even he, Biondello.

GREMIO

GREMIO Hark you, sir, you mean not her to

212—

TRANIO

TRANIO Perhaps, him and her, sir. What

213 have you to do?

PETRUCHIO

PETRUCHIO Not her that chides, sir, at any hand, I pray.

215

215

TRANIO

TRANIO I love no chiders,

215 sir. Biondello, let’s away.

LUCENTIO

LUCENTIO Well begun,

216 Tranio.

Aside

HORTENSIO

HORTENSIO Sir, a word ere

217 you go:

Are you a suitor to the maid you talk of, yea or no?

TRANIO

TRANIO And if I be, sir, is it any offence?

220

220

GREMIO

GREMIO No, if without more words you will get you hence.

TRANIO

TRANIO Why, sir, I pray, are not the streets as free

For me as for you?

GREMIO

GREMIO But so is not she.

TRANIO

TRANIO For what reason, I beseech you?

225

225

GREMIO

GREMIO For this reason, if you’ll know,

That she’s the choice226 love of Signior Gremio.

HORTENSIO

HORTENSIO That she’s the chosen of Signior Hortensio.

TRANIO

TRANIO Softly, my masters. If you be gentlemen,

Do me this right: hear me with patience.

230

230 Baptista is a noble gentleman,

To whom my father is not all231 unknown,

And were his daughter fairer than she is,

She may more suitors have, and me for one.

Fair Leda’s daughter234 had a thousand wooers,

235

235 Then well one more may fair Bianca have,

And so she shall. Lucentio shall make one,

Though237 Paris came in hope to speed alone.

GREMIO

GREMIO What, this gentleman will out-talk us all.

LUCENTIO

LUCENTIO Sir, give him head.

239 I know he’ll prove a jade.

240

240

PETRUCHIO

PETRUCHIO Hortensio, to what end are all these words?

HORTENSIO

HORTENSIO Sir, let me be so bold as ask you,

Did you yet ever see Baptista’s daughter?

TRANIO

TRANIO No, sir, but hear I do that he hath two:

The one as famous for a scolding tongue

245

245 As is the other for beauteous modesty.

PETRUCHIO

PETRUCHIO Sir, sir, the first’s for me, let

246 her go by.

GREMIO

GREMIO Yea, leave that labour to great Hercules,

247

And let it be248 more than Alcides’ twelve.

PETRUCHIO

PETRUCHIO Sir, understand you this of me, in sooth:

249

250

250 The youngest daughter whom you hearken for,250

Her father keeps from all access of suitors,

And will not promise her to any man

Until the elder sister first be wed.

The younger then is free, and not before.

255

255

TRANIO

TRANIO If it be so, sir, that you are the man

Must stead256 us all and me amongst the rest,

And if you break the ice and do this feat,

Achieve the elder, set the younger free

For our access, whose hap259 shall be to have her

260

260 Will260 not so graceless be to be ingrate.

HORTENSIO

HORTENSIO Sir, you say well, and well you do conceive.

261

And since you do profess to be a suitor,

You must, as we do, gratify263 this gentleman,

To whom we all rest264 generally beholding.

265

265

TRANIO

TRANIO Sir, I shall not be slack, in sign whereof,

Please ye we may contrive266 this afternoon

And quaff carouses267 to our mistress’ health,

And do as adversaries268 do in law,

Strive269 mightily, but eat and drink as friends.

270

270

GRUMIO and BIONDELLO

GRUMIO and BIONDELLO O excellent motion!

270 Fellows, let’s be gone.

HORTENSIO

HORTENSIO The motion’s good indeed and be it so,

Petruchio, I shall be your ben venuto.272

Exeunt

[Act 2 Scene 1]

running scene 3

Enter Katherina and Bianca Bianca’s hands tied

BIANCA

BIANCA Good sister, wrong me not, nor wrong yourself,

To make a bondmaid2 and a slave of me.

That I disdain. But for these other goods,3

Unbind4 my hands, I’ll pull them off myself,

5

5 Yea, all my raiment,5 to my petticoat,

Or what you will command me will I do,

So well I know my duty to my elders.

KATE

KATE Of all thy suitors here I charge thee tell

Whom thou lov’st best: see thou dissemble9 not.

10

10

BIANCA

BIANCA Believe me, sister, of all the men alive

I never yet beheld that special11 face

Which I could fancy more than any other.

KATE

KATE Minion,

13 thou liest. Is’t not Hortensio?

BIANCA

BIANCA If you affect

14 him, sister, here I swear

15

15 I’ll plead for you myself, but you shall have him.

KATE

KATE O, then belike you fancy riches more:

You will have Gremio to keep you fair.17

BIANCA

BIANCA Is it for him you do envy

18 me so?

Nay then you jest, and now I well perceive

20

20 You have but jested with me all this while.

I prithee sister Kate, untie my hands.

KATE

KATE If that be jest, then all the rest was so.

Strikes her

Enter Baptista

BAPTISTA

BAPTISTA Why, how now, dame?

23 Whence grows this insolence?—

Bianca, stand aside. Poor girl, she weeps.

25

25 Go ply thy needle,25 meddle not with her.—

For shame, thou hilding26 of a devilish spirit,

Why dost thou wrong her that did ne’er wrong thee?

When did she cross28 thee with a bitter word?

KATE

KATE Her silence flouts

29 me, and I’ll be revenged.

Flies after Bianca

30

30

BAPTISTA

BAPTISTA What, in my sight? Bianca, get thee in.

Exit [Bianca]

KATE

KATE What, will you not suffer

31 me? Nay, now I see

She is your treasure, she must have a husband,

I must dance33 barefoot on her wedding day,

And for your love to her lead34 apes in hell.

35

35 Talk not to me. I will go sit and weep

Till I can find occasion of36 revenge.

[Exit]

BAPTISTA

BAPTISTA Was ever gentleman thus grieved as I?

But who comes here?

Enter Gremio, Lucentio in the habit of a mean man, Petruchio with [Hortensio as a musician, and] Tranio, with his boy [Biondello] bearing a lute and books

GREMIO

GREMIO Good morrow, neighbour Baptista.

40

40

BAPTISTA

BAPTISTA Good morrow, neighbour Gremio.

God save you, gentlemen!

PETRUCHIO

PETRUCHIO And you, good sir. Pray, have you not a daughter

Called Katherina, fair and virtuous?

BAPTISTA

BAPTISTA I have a daughter, sir, called Katherina.

45

45

GREMIO

GREMIO You are too blunt. Go

45 to it orderly.

PETRUCHIO

PETRUCHIO You wrong me, Signior Gremio, give me leave.

46—

I am a gentleman of Verona, sir, To Baptista

That, hearing of her beauty and her wit,48

Her affability and bashful modesty,

50

50 Her wondrous qualities and mild behaviour,

Am bold to show myself a forward51 guest

Within your house, to make mine eye the witness

Of that report which I so oft have heard.

And for54 an entrance to my entertainment,

55

55 I do present you with a man of mine, Presents Hortensio

Cunning in music and the mathematics,

To instruct her fully in those sciences,57

Whereof I know she is not ignorant.

Accept of59 him, or else you do me wrong.

60

60 His name is Litio,60 born in Mantua.

BAPTISTA

BAPTISTA You’re welcome, sir, and he, for your good sake.

But for my daughter Katherine, this I know,

She is not for your turn,63 the more my grief.

PETRUCHIO

PETRUCHIO I see you do not mean to part with her,

65

65 Or else you like not of my company.

BAPTISTA

BAPTISTA Mistake me not, I speak but as I find.

Whence are you, sir? What may I call your name?

PETRUCHIO

PETRUCHIO Petruchio is my name, Antonio’s son,

A man well known throughout all Italy.

70

70

BAPTISTA

BAPTISTA I know him well. You are welcome for his sake.

GREMIO

GREMIO Saving

71 your tale, Petruchio, I pray,

Let us that are poor petitioners72 speak too:

Baccare!73 You are marvellous forward.

PETRUCHIO

PETRUCHIO O, pardon me, Signior Gremio, I

74 would fain be doing.

GREMIO

GREMIO I doubt it not, sir. But you will curse your wooing.—

To Baptists Neighbour, this is a gift very grateful,

76 I am sure of it. To express the like kindness, myself, that have been more kindly

77 beholding to you than any,

Presents Lucentio freely give unto you this young scholar, that hath been long studying at Rheims,

78 as cunning in Greek, Latin, and other languages, as the other in music and mathematics. His name is Cambio.

79 Pray, accept his service.

BAPTISTA

BAPTISTA A thousand thanks, Signior Gremio.

Welcome, good Cambio.—

But, gentle sir, methinks you walk83 like a stranger. To Tranio

May I be so bold to know the cause of your coming?

85

85

TRANIO

TRANIO Pardon me, sir, the boldness is mine own,

That, being a stranger in this city here,

Do make myself a suitor to your daughter,

Unto Bianca, fair and virtuous.

Nor is your firm resolve unknown to me,

90

90 In the preferment90 of the eldest sister.

This liberty is all that I request,

That, upon knowledge92 of my parentage,

I may have welcome ’mongst the rest that woo,

And free access and favour as the rest.

95

95 And toward the education of your daughters

I here bestow a simple instrument, Presents lute and books

And this small packet of Greek and Latin books:

If you accept them, then their worth is great.

BAPTISTA

BAPTISTA Lucentio

99 is your name? Of whence, I pray?

100

100

TRANIO

TRANIO Of Pisa, sir, son to Vincentio.

BAPTISTA

BAPTISTA A mighty

101 man of Pisa. By report

I know him well. You are very welcome, sir.— To Hortensio and Lucentio

Take you the lute, and you the set of books,

You shall go see your pupils presently.104—

105

105 Holla,105 within!

Enter a Servant

Sirrah, lead these gentlemen

To my daughters, and tell them both

These are their tutors: bid them use them well.

[Exit Servant, with Lucentio and Hortensio, Biondello following]

We will go walk a little in the orchard,109

110

110 And then to dinner.110 You are passing welcome,

And so I pray you all to think yourselves.

PETRUCHIO

PETRUCHIO Signior Baptista, my business asketh haste,

112

And every day I cannot come to woo.

You knew my father well, and in him me,

115

115 Left solely heir to all his lands and goods,

Which I have bettered rather than decreased.

Then tell me, if I get your daughter’s love,

What dowry shall I have with her to wife?

BAPTISTA

BAPTISTA After my death the one half of my lands,

120

120 And in possession120 twenty thousand crowns.

PETRUCHIO

PETRUCHIO And for that dowry I’ll assure

121 her of

Her widowhood, be it that she survive me,

In all my lands and leases123 whatsoever.

Let specialties124 be therefore drawn between us,

125

125 That covenants125 may be kept on either hand.

BAPTISTA

BAPTISTA Ay, when the special

126 thing is well obtained,

That is, her love, for that is all in all.

PETRUCHIO

PETRUCHIO Why, that is nothing, for I tell you, father,

128

I am as peremptory as she proud-minded.

130

130 And where two raging fires meet together

They do consume the thing that feeds their fury.

Though little fire grows great with little wind,

Yet extreme gusts will blow out fire and all:

So I134 to her and so she yields to me,

135

135 For I am rough and woo not like a babe.

BAPTISTA

BAPTISTA Well mayst thou woo, and happy

136 be thy speed!

But be thou armed for some unhappy words.

PETRUCHIO

PETRUCHIO Ay, to the proof,

138 as mountains are for winds,

That shakes not, though they blow perpetually.

Enter Hortensio [disguised as Litio], with his head broke

140

140

BAPTISTA

BAPTISTA How now, my friend? Why dost thou look so pale?

HORTENSIO

HORTENSIO For fear, I promise you, if I look pale.

BAPTISTA

BAPTISTA What, will my daughter prove a good musician?

HORTENSIO

HORTENSIO I think she’ll sooner prove

143 a soldier.

Iron may hold with144 her, but never lutes.

145

145

BAPTISTA

BAPTISTA Why, then thou canst not break her to

145 the lute?

HORTENSIO

HORTENSIO Why, no, for she hath broke

146 the lute to me.

I did but tell her she mistook her frets,147

And bowed her hand to teach her fingering,

When, with a most impatient devilish spirit,

150

150 ‘Frets, call you these?’ quoth she, ‘I’ll fume150 with them.’

And with that word, she struck me on the head,

And through the instrument my pate152 made way,

And there I stood amazèd153 for a while,

As154 on a pillory, looking through the lute,

155

155 While she did call me rascal fiddler155

And twangling Jack,156 with twenty such vile terms,

As had she studied157 to misuse me so.

PETRUCHIO

PETRUCHIO Now, by the world, it is a lusty

158 wench.

I love her ten times more than e’er I did.

160

160 O, how I long to have some chat with her!

BAPTISTA

BAPTISTA Well, go with me and be not so discomfited.

161 To Hortensio

Proceed in practice162 with my younger daughter,

She’s apt to learn and thankful for good turns.

Signior Petruchio, will you go with us,

165

165 Or shall I send my daughter Kate to you?

PETRUCHIO

PETRUCHIO I pray you do.

Exeunt all but Petruchio

I’ll attend166 her here,

And woo her with some spirit when she comes.

Say that she rail, why then I’ll tell her plain

She sings as sweetly as a nightingale:

170

170 Say that she frown, I’ll say she looks as clear170

As morning roses newly washed with dew:

Say she be mute and will not speak a word,

Then I’ll commend her volubility,

And say she uttereth piercing174 eloquence:

175

175 If she do bid me pack,175 I’ll give her thanks,

As though she bid me stay by her a week:

If she deny to wed, I’ll crave177 the day

When I shall ask the banns178 and when be married.

But here she comes, and now, Petruchio, speak.

Enter Katherina

180

180 Good morrow, Kate, for that’s your name, I hear.

KATE

KATE Well have you heard, but something hard

181 of hearing:

They call me Katherine that do talk of me.

PETRUCHIO

PETRUCHIO You lie, in faith, for you are called plain Kate,

And bonny Kate and sometimes Kate the curst,

185

185 But Kate, the prettiest Kate in Christendom,

Kate of Kate Hall, my super-dainty Kate,

For dainties187 are all Kates, and therefore, Kate,

Take this of188 me, Kate of my consolation,

Hearing thy mildness praised in every town,

190

190 Thy virtues spoke of, and thy beauty sounded,190

Yet not so deeply191 as to thee belongs,

Myself am moved192 to woo thee for my wife.

KATE

KATE Moved? In good time!

193 Let him that moved you hither

Remove you194 hence. I knew you at the first

195

195 You were a movable.195

PETRUCHIO

PETRUCHIO Why, what’s a movable?

KATE

KATE A joint stool.

197

PETRUCHIO

PETRUCHIO Thou hast hit it: come, sit on me.

198

KATE

KATE Asses

199 are made to bear, and so are you.

200

200

PETRUCHIO

PETRUCHIO Women are made to bear, and so are you.

KATE

KATE No such jade as you, if me you mean.

PETRUCHIO

PETRUCHIO Alas, good Kate, I will not burden

202 thee,

For knowing thee to be but young and light203—

KATE

KATE Too light

204 for such a swain as you to catch,

205

205 And yet as205 heavy as my weight should be.

PETRUCHIO

PETRUCHIO Should be?

206 Should — buzz!

KATE

KATE Well ta’en,

207 and like a buzzard.

PETRUCHIO

PETRUCHIO O slow-winged turtle,

208 shall a buzzard take thee?

KATE

KATE Ay, for a turtle,

209 as he takes a buzzard.

210

210

PETRUCHIO

PETRUCHIO Come, come, you wasp, i’faith, you are too angry.

KATE

KATE If I be waspish,

211 best beware my sting.

PETRUCHIO

PETRUCHIO My remedy is then to pluck it out.

KATE

KATE Ay, if the fool could find it where it lies.

PETRUCHIO

PETRUCHIO Who knows not where a wasp does wear his sting?

214 In his tail.

215

215

KATE

KATE In his tongue.

PETRUCHIO

PETRUCHIO Whose tongue?

KATE

KATE Yours, if you talk of tails,

217 and so farewell.

PETRUCHIO

PETRUCHIO What, with

218 my tongue in your tail? Nay, come again.

Good Kate, I am a gentleman.

220

220

KATE

KATE That I’ll try.

220

She strikes him

PETRUCHIO

PETRUCHIO I swear I’ll cuff

221 you, if you strike again.

KATE

KATE So may you lose your arms:

222

If you strike223 me, you are no gentleman,

And if no gentleman, why then no arms.

225

225

PETRUCHIO

PETRUCHIO A herald, Kate? O, put me in thy books!

225

KATE

KATE What is your crest,

226 a coxcomb?

PETRUCHIO

PETRUCHIO A combless

227 cock, so Kate will be my hen.

KATE

KATE No cock of mine, you crow too like a craven.

228

PETRUCHIO

PETRUCHIO Nay, come, Kate, come, you must not look so sour.

230

230

KATE

KATE It is my fashion,

230 when I see a crab.

PETRUCHIO

PETRUCHIO Why, here’s no crab, and therefore look not sour.

KATE

KATE There is, there is.

PETRUCHIO

PETRUCHIO Then show it me.

KATE

KATE Had I a glass,

234 I would.

235

235

PETRUCHIO

PETRUCHIO What, you mean my face?

KATE

KATE Well

236 aimed of such a young one.

PETRUCHIO

PETRUCHIO Now, by Saint George, I am too young

237 for you.

KATE

KATE Yet you are withered.

PETRUCHIO

PETRUCHIO ’Tis with cares.

239

240

PETRUCHIO

PETRUCHIO Nay, hear you, Kate. In sooth you scape

241 not so.

KATE

KATE I chafe

242 you, if I tarry. Let me go.

PETRUCHIO

PETRUCHIO No, not a whit. I find you passing gentle.

’Twas told me you were rough244 and coy and sullen,

245

245 And now I find report a very liar,

For thou are pleasant,246 gamesome, passing courteous,

But slow247 in speech, yet sweet as spring-time flowers.

Thou canst not frown, thou canst not look askance,248

Nor bite the lip, as angry wenches will,

250

250 Nor hast thou pleasure to be cross250 in talk.