The popular Japanese expression “Ganbatte kudasai” (“Please do your best!” or “Go for it!”) is particularly appropriate in a discussion on the Japanese language. It may be one of the hardest languages to master, certainly in its written form, but Japanese is now recognized as one of the world’s important modern languages. Self-evidently, learning even a little spoken Japanese will make visiting or living in Japan much easier. In addition, the Japanese respond warmly to anyone attempting to learn their language—indeed, the effort to hold the simplest day-today conversations yields disproportionate rewards in terms of Japanese affirmation and practical outcomes.

Of course, it is entirely possible to live in metropolitan Japan without speaking a word of Japanese, but it would be expecting a lot of your hosts and Japanese colleagues to get everything right in English all of the time.

In addition to the more than 127 million people living in Japan, it is worth noting that Japanese is also spoken abroad wherever Japanese people have settled—in North and South America (the biggest Japanese population outside Japan is in Brazil) and in Hawaii—and by an estimated three million people around the world, including many Chinese, as well as schoolchildren in North America, the UK, Australia, and New Zealand, for whom Japanese sometimes forms part of the curriculum.

Adult literacy and numeracy in Japan is virtually 100 percent, the highest in the world. How has this come about? Much is said about the rigor of the Japanese education system, where rote learning is still a fundamental teaching tool and the “Three Rs” (reading, writing, and arithmetic) continue to dominate the curriculum. But the learning of the language itself is surely a major factor in terms of advancing both the intellect and the memory.

The Japanese script uses a mixture of Chinese characters or ideograms (kanji) plus two phonetic “shorthand” systems (known as syllabaries)—katakana and hiragana, which are derived from kanji and contain forty-six symbols each. Katakana is used to write foreign names and loan words, and hiragana is used on railway signboards, sometimes on menus, and so on. Roman script (romaji) is also used.

The number of kanji in regular use is approximately 2000. These must be mastered by the end of lower secondary school—compulsory education finishes at the age of fifteen, but practically every child in Japan (95 percent) goes on to upper secondary/senior high school for a further three years. The two syllabaries also have to be mastered at school, of course. Furthermore, the Arabic numerals have to be learned, as well as writing with brush and ink, which involves a considerable investment in time, particularly at primary school.

READING THE RAILWAY SIGNS

A typical railway signboard will give the name of the station in a mixture of scripts for the convenience of everyone (including youngsters who haven’t yet mastered enough kanji, and foreigners who can’t read Japanese). Usually, the top row of characters will be in kanji, and below that will be hiragana and then romaji (Roman script). At the very bottom are left and right arrows with kanji above pointing to the previous station (with name) and the next station (with name).

Japanese does not fit easily into any of the “family trees” of the world’s languages. On the one hand, it has a grammatical affinity with Korean and Central Asian languages; on the other, when spelled out, it looks strikingly similar to some Polynesian languages. In fact, one of the most provocative theories about the origins of Japanese is that it is a Central Asian language spoken with a Polynesian accent—in the same way that French is a form of Latin spoken with a Gallic accent.

Unlike Chinese (from which many Japanese kanji were originally imported) with its formidable array of tonal levels, Japanese is not an inflected language and consequently is comparatively easy to pronounce (see over), which is encouraging for beginners. However, every word of Japanese you learn will be a “one off” item of vocabulary. There are no familiar linguistic landmarks and word families as there are in European languages! But there are rewards for your efforts. For example, unlike European scripts, Japanese is written vertically (top to bottom, right to left), making it very easy to read the title of a book on a bookshop shelf without having to turn your head ninety degrees! Of course, a Japanese book, by definition, is also “back to front!”

Clearly, therefore, there is no shortcut to learning Japanese. Mastery of the language will require daily study and revision over several years. But for those looking to achieve “survival” Japanese (in both speaking and comprehension), determined application over six months is usually the agreed time frame.

Fortunately for beginners, a “helping hand” is available: the Japanese are also extremely fond of using loan words from Western languages, with English words predominating (see opposite).

Although the pronunciation of Japanese is relatively easy, there are some quicksands in comprehension if you fail to grasp the difference between the long vowel and the short vowel. In Romaji the long vowel is indicated by using a line (macron) above the ō and ū. For example, shujin with a short u means “my husband,” whereas shūjin with a long ū means “jailbird.” Kyōto is Kyoto, the ancient capital; whereas kyotō is “a big shot,” and kyōtō is an “assistant principal” of a school or college.

Also, it is important to pronounce the vowels in a dipthong quite distinctly. Thus, the Japanese surname Maeda is pronounced ma-e-da (not rhyming with “Maida” as in Maida Vale in London); “geisha,” on the other hand, is usually not split into ge-i-sha, but pronounced with a long ē, gēsha; whereas maiko, the apprentice geisha, is pronounced ma-i-ko.

Finally, the e at the end of a word in Japanese is sounded, thus saké (rice wine), netsuké (the famous miniature carved toggles), and Nakasoné (the former prime minister). Also, remember that, for the most part, Japanese nouns do not distinguish between singular and plural; so the word hon means both book and books, denwa is telephone and telephones.

| VOWELS ARE PRONOUNCED AS FOLLOWS: | |

| a – as in far | o – as in gone |

| e – as in men | u – as in put |

| i – as in meet | |

Famously, Japanese airlines have had to cope with the joke about staff wishing their customers “a nice fright” on their journey to “Rondon”—the point being that the Japanese language does not distinguish between the “l” and “r” sounds, and invariably the “r” option is selected for ease of delivery. As teachers of English as a foreign language know, the “l” sound for Japanese students is not easy to achieve, and is basically a problem involving the placement of the tongue in the mouth.

As we have seen, the Japanese have imported loan words, mostly from English, in order to expand their contemporary vocabulary and meet the needs of modern society. Here is a selection that may bring a ready smile to native speakers of English! (Remember that the Japanese often have to add in the vowels “ro” and “ru” to render the loan words pronounceable in Japanese!)

arukoru alcohol; asupirin aspirin; azukaru to look after, take care of (belongings); ba bar; baggu bag; butsu boots; chekku auto check-out; chiizu cheese; chokoreto chocolate; dababru double (room); departo department store; dorai kurliningu dry cleaning; eakon air conditioning; erebeta elevator; fasuto fudo fast food; furonto reception desk (hotel); gurasu glass; handobaggu handbag; hoteru hotel; hotto doggu hot dog; kohii shoppu coffee shop; kuroku cloakroom; meron mellon; nekkuresu necklace; pasupoto passport; purinto print; puroguramu program; rabu hoteru love hotel; rajio radio; raunji ba lounge bar; rentaka rental car; resutoran restaurant; sarariiman businessman; serusuman sales person; shinguru single (room); sofuto dorinku soft drink; tabako cigarette; terebi television; uisukii whiskey; wa puro word processor; yusu hosuteru youth hostel.

No single phenomenon can encapsulate the essence of a country, least of all a sophisticated culture like that of Japan, but it is fun to explore the options. We have considered the singular nature of Japan as a country and people “apart,” with a distinctive language and religion, and a way of life that is informed by a groupist or consensus-driven philosophy, underpinned by many and varied protocols governing personal relationships and social exchange.

We have glimpsed Japan’s unique artistic heritage, and the remarkable way in which the past coexists with the present, and the natural world continues to inform modern life.

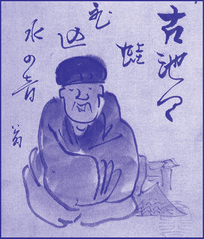

A wonderful example of this can be found in Japanese poetry, in a seventeen-syllable form of verse known as haiku. The great master of this particular form of poetry was Matsuo Basho, who died in 1694. Haiku, which is rooted in the natural world, is universally appreciated in Japan, and reinforced by numerous annual haiku events and competitions. This is one of Basho’s most famous haiku:

Listen! A frog

Jumping into the stillness

Of an ancient pond!

(Transl., Dorothy Britton)