James Tarr surprisingly didn’t feel a chill as he hiked to the end of his grandparents’ driveway to pick up the mail. The mercury hovered at 37 degrees, balmy for two days after Christmas 1922 in central Wisconsin.

Twenty-year-old James looked around at the eighty acres Grandpa James Chapman had cultivated into a prosperous farm, with crops and dairying, having a good herd of graded cattle with a pure-bred Holstein sire at the head. Just a couple years earlier, Chapman had built a modern barn with a basement.

James’s mom, Lorena, had grown up here, an only child, nurtured and loved by her parents, James and Clementine. They shared their affection with young James and his siblings, Manning and Sadie, and on their grandparents’ farm the children were experiencing much of the life their mom had known as a child. Grandpa James had one of those great bushy mustaches that tickled when he gave kisses and held leftovers from an earlier meal.

Grandpa James and Grandma Clementine were popular in their neighborhood, and James was well-respected in Wood County. He served as chairman of the county board and as a member of the county drainage board. Various businesses sought his involvement as an investor, a consultant, anything to be able to associate with him.

So it wasn’t a surprise to find some straggler Christmas cards in the mailbox that day. It was the foot-long gray package that intrigued the boy, especially since it had no return address and listed his grandparents’ address as “Marshfild, Wisconsin,” instead of the accurate name, Cameron Township, which is located just a few miles south of Marshfield.

James kicked the slushy snow as he returned up the driveway. He stomped out his shoes before going back into the house and handing the package to his grandparents, who were in their dining room. As his grandma held the Christmas cards, his grandfather sat down with the package on his knees and took out his pocket knife to cut the wrapping paper lengthwise.

Clementine leaned over his shoulder and he cut through the twine. She never got to see what was inside the package.

Moments later, Tarr stumbled to the phone and called a family friend, Ole Gilberts, at the Klondyke General Store, a mile away from the home.

“For God’s sake, come up here!” he shouted into the phone.

Gilberts rushed to help the Chapmans. He later told authorities that when he got to the farmhouse, he found James Chapman lying unconscious near the dining room, with his left hand blown off and a bleeding leg. Clementine was face down in a pool of blood, dying from massive chest and stomach wounds and significant internal bleeding. Tarr suffered only minor physical injuries.

The dining room walls and ceiling looked like Swiss cheese studded with metal fragments. A six-inch iron pipe, stuffed with explosive picric acid, a dynamite substitute, was lodged in the Chapmans’ floor. Picric acid, usually used to clear land, left the odor of antiseptic soap. Those first on the scene after the blast swore they could smell it.

In this case, it had been used to make a bomb. The pipe had been encased in a block of wood, and the twine around the package had served as the trigger.

Authorities, including Wood County Sheriff Walter Mueller, wondered whether the motive was political, perhaps retaliation for a vote Chapman had cast that a neighbor didn’t like. But James Chapman had served his county for nearly two decades, and he had taken many controversial votes during his time in office. Recently, he had voted to authorize money to crack down on moonshiners and bootleggers to implement Prohibition, ratified in the form of the 18th Amendment to the US Constitution a couple of years earlier. Or maybe it had something to do with a ditch the county drainage board and Chapman had supported that headed through the southern part of the county. Many farmers didn’t like it because it traversed their properties. Just a couple of months earlier, a suspicious fire had destroyed the barn of one of Chapman’s fellow drainage commissioners. A few months before that, the equipment set to dig the ditch had been blown up with dynamite.

Forty-four-year-old John Magnuson, a native of Sweden, had fought for the British in the Boer War in Africa before owning a garage in Chicago and then moving north to eighty acres in Wood County. To authorities he was the most outspoken opponent of the drainage ditch. Witnesses said he had threatened violence against those who supported the ditch. Chapman later told investigators looking into the explosion at his house that Magnuson had threatened a lawsuit to stop the drainage ditch. If the best Chicago lawyer couldn’t stop the project, Magnuson said his guns would.

While the general public was fixated on the crime that killed Clementine Chapman, authorities were fixated on Magnuson. He would be arrested and charged with first-degree murder.

Just two days after the explosion at the Chapman home, the nearby Wisconsin Rapids Daily Tribune reported on its front page that “Marshfield has been transformed from a peaceful city to one of hubbub due to the influx of the government operatives and to the large press gallery which has assembled there. It is regarded by the press to be one of the biggest stories of the year and over a dozen of special correspondents were sent to the scene immediately by press associations and metropolitan newspapers.”

Prosecutors knew that the case, albeit “premeditated . . . to effect the death of a human being with malice aforethought,” would be circumstantial in nature. For example, no one had seen Magnuson make the bomb. No one had seen him put it in the mail along Rural Route 5, which was nowhere near his property. No fingerprints were found on the bomb materials left behind by the explosion.

The prosecution gathered handwriting experts from New York, Milwaukee, and Chicago. They brought in an engineering professor from the University of Wisconsin–Madison to testify that steel from a gas engine on Magnuson’s farm matched the steel in the bomb trigger. A UW chemistry professor matched the bomb’s metal with metal found at Magnuson’s.

And to Judge Byron B. Park’s Branch 2 courtroom, prosecutors brought a thirty-seven-year-old xylotomist, an expert in wood identification, to weigh in on the fifty-one wood shavings and chips found under the lathe in Magnuson’s workshop. The balding judge in his three-piece suit looked over his wire-rim glasses at a type of forensic science expert witness he’d never seen in his courtroom before.

Ever meticulous, Arthur Koehler had analyzed all fifty-one samples under his microscope. Now he told Stan Peters, the foreman of the jury, and his fellow Wood County citizens that forty-six of the samples were white oak. One was hemlock, and one was ash.

And three of the chips and shavings investigators had brought to Koehler’s Madison laboratory were white elm, the same wood from which the bomb casing had been constructed. According to Koehler, those wood chips displayed the “beautiful chevron-like distribution of pore structure on the cut surface.” The newspaper headline called Koehler’s testimony a “Blow to Bomb Defense” and “the most important” of the expert testimony delivered in court.

Despite the defense attorney lamenting that the case against his client was solely circumstantial in nature, and despite Magnuson protesting to the court, “Time will prove my innocence,” the Swede was convicted of murder.

For Koehler, wood identification, while new to a courtroom in 1923, was standard practice.

Arthur Koehler was born in 1885 on a farm south of Mishicot, which was about eight miles north of Manitowoc, nestled nicely along Lake Michigan and at the mouth of the Manitowoc River. President Andrew Jackson had authorized land sales for the region in 1835, and Koehler’s parents, Louis and Ottilie, took advantage four decades later, purchasing eighty acres for $1,800.

Louis bought the first combined reaper and mower in the area, cutting not only his own grain, but that of his neighbors as well. He also bought the first gas engine in the neighborhood and used it to saw wood at one dollar an hour.

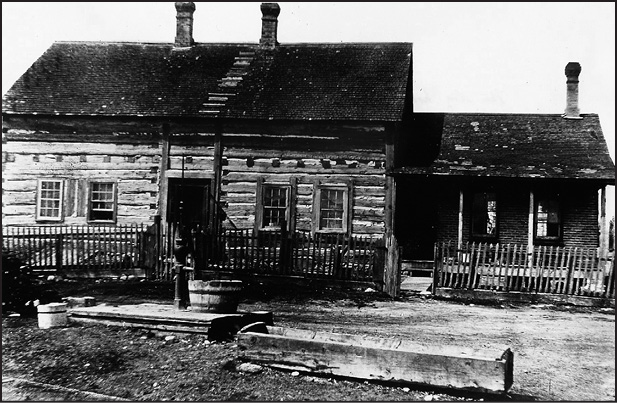

Arthur Koehler was born in 1885 in this farm house near Manitowoc, Wisconsin. He was the sixth of nine children born to Louis and Ottilie Koehler. Four of those children would die before the age of 10. (Courtesy: George E. Koehler)

The Koehlers had five cows, two horses, a wagon, a sled, and a sow at the beginning. Shortly after moving in, Louis planted one hundred apple trees for use at home and for sale. He put in berry bushes as well: blackberries, strawberries, and black, red, brown, and yellow raspberries. They grew oats, rye, and peas. The cows provided milk and butter for every meal, with “a considerable quantity” of butter to be sold at market as well, along with eggs from the Koehlers’ chickens.

But the Koehler family derived most of its income from bees. The hive located on the farm when the Koehlers bought it died that first winter, as did replacement hives he bought the following winter. Louis got a number of books on the subject and built a bee cellar to protect them from inclement weather, and by 1906 his apiary would number 250 hives. It was profitable as early as 1891, when Louis sold more than 10,000 pounds of honey at 18 cents per pound from 130 hives.

Louis’s interests didn’t stop at farming and bees. He gave eulogies for community members when the minister wasn’t available. He extracted teeth. One time he sewed up a young man cut by an axe using nothing more than an ordinary needle and thread.

But his passion was carpentry. The year Arthur was born, 1885, Louis built Ottilie a brick kitchen and turned the old frame kitchen into his carpentry shop. Once he built a coffin and lay down in it to give Ottilie a start and him a laugh.

The matriarch of the Koehler family was too busy for such shenanigans. “Ottilie milked the cows, raised chickens, knit socks, wove cloth and made clothing for the children,” Ben Koehler, Arthur’s brother, would later write. Ben’s wife, Edith, said of her mother-in-law, “I never saw anyone with more patience. . . . I feel that she was the most unselfish woman I ever met. I had great respect for her. I never heard her say anything against anyone. She was a truly Christian woman.”

She needed to be, with the losses she and Louis experienced. Both of their first two children, William and Martha, died before their first birthdays. Their third child, Amanda, was very healthy, but at just over a year old, she choked on a plum pit and died of suffocation.

Hugo, born in 1881, would be the first of the Koehler children to make it to his second birthday. Lydia was next, born in 1882. Arthur Koehler was the sixth child born to Louis and Ottilie, arriving in 1885. Three more boys, Ben, Walter, and Alfred, would come over the next eleven years.

Tragedy would strike again when Arthur was seven, as Lydia and Ben suffered from a severe case of diphtheria in 1892. Ben would recover, but Lydia died two weeks shy of her tenth birthday.

“One hour before she left us she prayed to God to leave her with her papa and mamma and her brothers,” Louis wrote in the American Bee Journal. “Still the Great Shepherd took her away from us to a better land, where the storms of this life will never reach her any more, and where all diseases are unknown—to a home in Heaven. What a joyful thought.”

Arthur grew up happy, spending hours upon hours in his father’s workshop. He made miniature threshing machines during bean harvesting time, crafting teeth for the cylinder out of cut shingle nails with their heads flattened on an anvil. These activities weren’t without episode, either, with a narrow cutter head once cutting a triangular hole in his fingernail. It happened in the dead of winter, and Arthur later reported that “the cold seemed to increase the pain which was excruciating.”

Despite growing up on a farm, he always “preferred winter work in the woods to summer jobs. A particularly repulsive job in the fields was to shock bundles of rye or barley on a hot summer’s day with the barbed ‘beards’ of the grain finding their way inside my shirt.” In winter, however, he found “there was something fascinating about the cold stillness of the forest; or, if the wind was blowing, to hear it moan in the pine tops overhead.”

The only rule his father had for him in the shop was that he was not allowed to use the saw or hammer on Sundays, as it might be disrespectful to the neighbors. The Koehlers weren’t particularly religious, although Louis did say grace in German before every meal.

In fact, Arthur and his brothers spoke German when their parents were included in the conversation and English to each other. The five boys were close, literally and figuratively, three of them at one time sleeping in an attic room usually used for storage. Walter remembered once being upstairs with Hugo and Arthur in the middle of the winter and having to “shake the snow off his underwear before dressing.”

They weren’t the type of family to play games together or dance around the phonograph. When Arthur’s parents had spare time, they chose to read. His father liked his children to keep quiet after dinner so he could read the paper undisturbed.

Arthur’s affection for learning was apparent at an early age. He began attending school at age three and went fulltime after he turned four. He finished eighth grade at age twelve and then moved in with Hugo and their maternal grandmother in Manitowoc so he could attend the high school, which was nearly ten miles from the farm. He worked as a school janitor and in various stores to help support himself.

He graduated high school at age sixteen with a focus in English and a thesis on Arctic exploration. His commencement program mistakenly listed him as “Arthur G. Koehler,” the only time he would have a middle initial until getting involved in the Lindbergh case more than three decades later.

In his junior year, Arthur began chronicling literally every expense he incurred, a practice he would follow for the next sixty-three years. On the first page of his first financial ledger, he wrote: “Though money talks, As we’ve heard tell, To most of us it says—‘Farewell.’”

The very first cash received came in a $5.00 payment for his janitorial services and an additional $1.10 from “Grandma.” He already had seventeen cents in savings for an opening balance of $6.17 for the month of June 1900. On the spending side, on June 2 he spent seventeen cents on a “Fishing outfit” and another six cents on laundry. He balanced his new ledger just two days later—his birthday, June 4. He accounted for every penny, including numerous five-cent payments for ice cream, cookies, and banjo strings.

In his senior year, he spent and earned more, including spending eighteen cents for each book of the Leather Stocking Tales series by James Fennimore Cooper. For his graduation from high school, he spent five cents on firecrackers, fifty cents to attend the banquet, and five cents for a banana. He left high school and headed back to the family farm with $13.67 in his pocket.

To say Arthur Koehler lacked direction after high school would be accurate. He bounced around in Manitowoc, working for a bookstore, a wholesale fruit dealer, and at the general store, and then moved back home from 1903 to the fall of the following year. He was nineteen years old, with no job and no career. But he had developed a passion for photography that would stay with him for the rest of his life. As an early Christmas present to himself in 1903, he spent $5.14 for a “camera outfit,” including developing paper, chemicals, a tripod screw, and exposure tables.

That fall, he moved to Milwaukee to work for a wholesale candy dealer who offered room and board as part of the compensation. Arthur delivered the candy and took care of the horses that got him to where he needed to go.

His older brother, Hugo, got him a grocery clerk job in Ohio in the fall of 1905. He was earning ten dollars every two weeks with room and board covered. He closed the year and his first ledger with a balance of $108.80.

The second edition begins with three quotes, including from the business magazine Collier: “As a man spends his money, so is he.”

Another business magazine made an even greater impact on Arthur. Success was founded by Orison Swett Marden, who encouraged readers that “all who have accomplished great things have had a great aim, have fixed their gaze on a goal which was high, one which sometimes seemed impossible.” Marden was America’s first true self-help guru. Like Arthur, he had been born on a farm with modest means, but unlike Arthur, Marden had gone to college and graduate school before embarking on his career. To Marden, education was vital to success.

The monthly publication he founded in 1897 had half a million subscribers just a decade later, meaning it likely was read by roughly three million people. To Arthur, it certainly was worth the ten cents per issue. He had read it off and on during his time in Milwaukee, but the move to Ohio seemed to fuel his own desire to succeed, and he bought the magazine every month. He liked it so much, he ended up working to sell subscriptions.

If the publication inspired Arthur to go to college, his preferred area of study percolated after he spent the 1907 New Year’s back at the family farm. His trip to Ohio took him through Chicago’s Union Depot, created in 1874 by five separate railroads. The station opened to Canal Street and stretched from Madison to Adams Streets. Commercial vendors lined the building that served as the main passenger thoroughfare to the city. In addition to buying the January edition of Success from an area merchant, Arthur braved Chicago’s westerly winds and relatively mild 40-degree temperatures to spend two dollars on a book called Our Native Trees.

His brother Ben said Arthur started thinking about a career in forestry right after high school, after he heard a speaker discuss the topic. But it wasn’t until he picked up the seminal book in the field by naturalist Harriet L. Keeler that the idea took shape.

The book came out in 1900 to rave reviews. The New York Times called it “well-written and thoroughly interesting.” Keeler wrote eloquently about trees from the Atlantic Ocean to the Rocky Mountains and from Canada to the southern states.

Arthur wanted to learn more and would enroll at Lawrence University in Appleton, Wisconsin, in the fall of 1907 at age twenty-two. On his first day in botany class, he was paired up with Ethelyn Smith to go to the home of a woman who raised petunias and bring back a flat for the rest of the students.

His third financial ledger tells the tale of a blossoming romance with the young woman, three years his junior, from Evansville, just south of the Wisconsin state capital of Madison. He took Ethelyn to a “Magic Show” for a dollar, bought her ice cream and candy for a nickel each, and treated her to meals and to the theatre for two dollars.

The Lawrence yearbook, the Ariel, mentions their relationship, proclaiming during their freshman year spring break that “Koehler wanders about Botany lab, but all in vain: Miss Smith has left for home.” The next year, the yearbook postulated, “Did you ever see Koehler without Miss Smith on Sunday evenings?”

He put his passion for photography to work capturing his newest passion. She was tall, standing above most other women on campus and even an inch or two above his five-foot- nine frame. The camera liked her, as did the photographer behind it. She exuded warmth and an openness emblematic of a woman happy to dote on those she encountered.

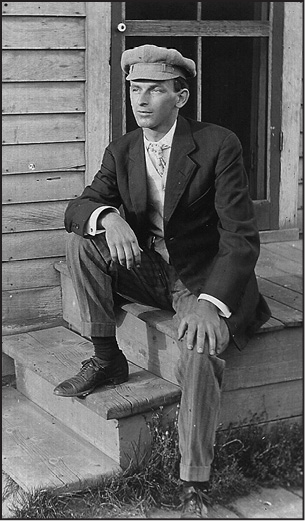

Arthur Koehler worked at a grocery store in Ohio and sold subscriptions to a leading business magazine before going to college. Here he is at age 23 before his sophomore year at Lawrence University in Appleton, Wisconsin. He would finish his degree at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor. (Courtesy: George E. Koehler)

When he wasn’t focusing his lens on Ethelyn, Arthur focused on mathematics, averaging 93 over six different courses. Despite being brought up in a home where his parents spoke the language, he scored only a 90 in third-year German. His lowest grade was in freshman elocution, a 78, which he raised to a 90 in his sophomore year.

His income came primarily from a serving job in the Ormsby Hall dining room, supplemented by selling his photos, which his younger brother Ben would point out proved to be “quite profitable work.”

Arthur knew all along he couldn’t study forestry at Lawrence, so in the fall of 1909, after a five-day “vacation” to see Ethelyn in Madison and Evansville and one more trip to Appleton, he crossed Lake Michigan on the ferry boat and began his junior year at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor.

He took his first job in the field, working in the Botany Department for $7.20 per month. He supplemented that by working as a commercial photographer, taking group and individual pictures, as well as waiting tables. He continued to see Ethelyn despite the distance between them.

He bought more publications related to forestry, including a booklet called Timber published by the US Department of Agriculture. Arthur started his senior year in Ann Arbor with a balance of $601.17 in his ledger. He sold his waiter’s coat and apron for fifty cents because he was hired on campus as an assistant instructor in tree identification, a job he later said “helped very much in fixing in my mind how the different species of trees can be distinguished and in permanently increasing my interest in life outdoors.”

His interest in Ethelyn remained a constant as well, and the Lawrence yearbook staff continued its chronicling of the now long-distance relationship, writing, “What would happen if Ethelyn Smith failed to hear from Ann Arbor?”

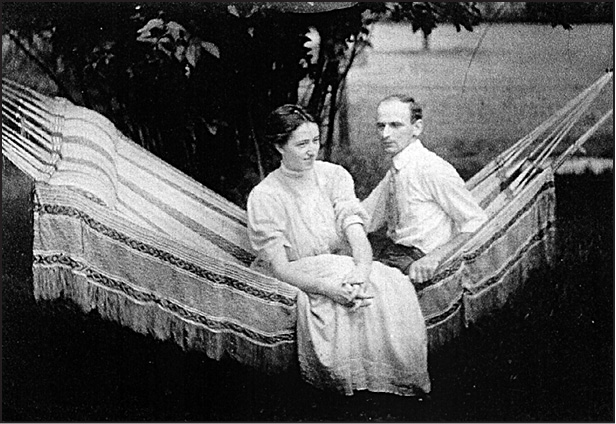

Arthur was partnered with Ethelyn Smith on their first day of Botany class at Lawrence. They would be married roughly five years later in 1912. (Courtesy: George E. Koehler)

That would not be an issue. The Christmas before their last semester in college, they met in Milwaukee and got engaged. Arthur graduated and left the university on June 21, traveling back to Evansville to see Ethelyn before going to work for the summer for the Wisconsin Forestry Department near Trout Lake, in the northern part of the state. He apparently did so more for the experience than the wages, since his ledger records little income—or expenses, for that matter—during that summer job.

Arthur returned to Ann Arbor that fall to start postgraduate work in forestry while still earning twenty dollars a month from the university for teaching undergraduates in that field. Only a month later, after paying fifty cents to watch his Michigan Wolverines wallop Ohio State 19–0 behind All-American Stanfield Wells, Arthur left campus for Washington DC, and a job with the US Forest Service as an “assistant in the study of the cellular structure of wood.”

His first check came on November 16, a whopping $41.00. He’d receive another $42.33 from the “U.S.,” according to his ledger, for a total of $83.33 per month. The goal was to save money. Ethelyn was doing the same, teaching high school math in a small town in western Wisconsin.

Over Christmas 1912, he took an unpaid vacation to head home for nearly two weeks. During that time, he separated from his fiancée long enough to take the federal Civil Service exam. He needed a 70 to pass, which would make him eligible for promotion opportunities. He scored 87.60 on the practical questions, 85 on the thesis, and 92 on the education, training, and experience component. It was another step, like those he had read about so often in Success, toward bettering himself and creating a better future for himself and Ethelyn.

The couple planned to be married in October, but in August Arthur got sick, threatening the event. Purchases mentioned in his journal—a nasal atomizer, syringe, and two medications—suggest he thought he had a cold, but four days later he paid $1.50 for a “Taxi to Hospital.” A full seven weeks passed before the next expense was recorded. The cold was in reality typhoid fever and required a long stay at Providence hospital at a cost of $100.75. Further costs incurred included $70 to a Dr. Yates.

Before the medical bills came in, he had nearly doubled his savings, from $461.77 when he left Ann Arbor to $899.25 by October 1. That’s when he left for Wisconsin, “to recuperate and also to get married,” as Ben would later write. Two days before the October 16 wedding, Arthur started spending some of that money on things he needed for the event, including twenty-five cents for a haircut (basically a trim around the sides, as he was already bald on top of his head) and ten cents for a shave. The biggest expenses would be four dollars for shoes and four dollars for a ring.

The early-morning ceremony would be on Ethelyn’s twenty-fourth birthday at the farm where she grew up. Her new husband was twenty-seven.

Arthur got married with $627.80 on hand, finishing the last open space on his third financial ledger. The fourth, a large, gray, cloth-bound book, began with a five-dollar payment to Reverend Charles E. Coon, a Methodist pastor, for officiating the wedding, two train tickets to Manitowoc for $6.58, and the beginning of their trip back to Washington, where they would start their new lives together.

They would rent for their first couple of months there before a disagreeable landlady hastened their plans to buy a home in December 1912. They put $300 down on a three-bedroom, two-bathroom $1,300 house at 167 Uhland Terrace, in the northeast quadrant of the city. It was off of North Capitol Street, about three miles from the Department of Agriculture headquarters on Independence Avenue.

By that time, Ethelyn was pregnant and they were enjoying what Washington had to offer. Ethelyn wrote home that “it is so beautiful here . . . the most beautiful city I ever saw or imagined.” They saw Ben Hur at the theatre, went to movies, even attended the inauguration of Woodrow Wilson in January 1913.

Kathryn Marie Koehler was born on August 20, 1913, in Madison, where Ethelyn had spent the last few months of her pregnancy at her parents’ newly built home on the city’s near west side. The Smiths had sold their farm and moved to the city to live near Ethelyn’s Aunt Cora, her mother’s sister.

Arthur returned to Washington a few days after Kathryn’s birth, and mother and daughter would join him in late September. Despite the family’s enjoyment of where they lived, they were planning a move roughly a year later, as Arthur had applied for and was accepted as a xylotomist with the US Forest Service in Wisconsin. The job would pay $1,000 per year and would take them back to Madison.

Family lore has Ethelyn’s father lying awake all night as he contemplated how the new home he was building for his retirement could be expanded to accommodate an additional family of three. Arthur and Ethelyn put their Uhland Terrace home up for sale. Before they sold it to G. L. Keenan, who provided a down payment of $100, the total family savings was only $67.99.

The Koehlers left for Madison on January 14, 1914, for Arthur’s position, which was at a new facility called the Forest Products Laboratory. It was an assignment his Washington colleagues didn’t understand. They openly pitied him for being sent to “Indian Country.”

In reality, Arthur Koehler and his family were being sent home. And they couldn’t have been happier about it.