‘WAS IT EDWARD IV who breakfasted on a buttock of beef and a tankard of old ale every morning?’ asked Morley.

‘It may have been, sir.’

‘Well, we don’t.’

‘No,’ I agreed.

‘Cup of hot water with a slice of lemon. Bowl of oatmeal,’ said Morley, tapping his spoon decisively on the side of his bowl. ‘Sets a man up for the day. Full of goodness, oatmeal. Steel-cut. Pure as driven snow.’

‘Pass the sugar, would you?’ said Miriam. ‘Indispensable, wouldn’t you say, Sefton? Utterly tasteless without, isn’t it? Like eating gruel.’

‘Gruel? Gruel?’ said Morley, before embarking on a short excursion on the history of the word, punctuated by Miriam’s protests and my own occasional weary agreements.

It was the morning after the night before, and I was enjoying my first taste of breakfast in the dining room at St George’s, which was not a household, I came to realise, that liked to ease its way into the day. There was neither a halt nor indeed even a pause in the relentless clamour of argument and quarrelling that echoed around the place like trains at a continental railway station. The conversation – to quote Sir Francis Bacon, or possibly Dr Johnson, or Hazlitt, certainly one of the great English essayists, who Morley liked to quote at every opportunity, and who I now, in turn, like to misquote – was like a fire lit early to warm the day and once lit was inextinguishable. Even when engaged in apparently casual conversation, Morley and his daughter exchanged verbal thrusts and parries that could be shocking to the outsider. For his part, Morley was not a man who brooked much disagreement, and his daughter was not a woman who liked to be bested in argument: and so the sparks would fly. All houses, of course, have an atmosphere – some pleasant, some not so pleasant, and some merely strange, no matter how humble nor how grand. The atmosphere of St George’s was one of a noisy Academy, presided over by Socrates and his rebellious daughter.

‘Sleep well?’

‘He’s not a child, Father. “A dry bed deserves a boiled sweet.”’

‘Sorry, I—’

‘Ignore her, Sefton. She only does it to provoke.’

‘Are you feeling provoked, Sefton?’ asked Miriam.

‘Erm. No. I don’t think so.’

‘Good,’ said Morley. ‘Dies faustus, eh? Dies faustus! All set?’

‘I think so, Mr Morley.’

‘Good, good. First day. Gradus ad Parnassum. Miriam will be driving us, in the Lagonda.’

‘Very well.’

‘Until you get the hang of it.’

‘Get the hang of it!’ snorted Miriam.

‘Anyway, I thought it would be nice for you to accompany us on the first outing. And I’ll need to brief Mr Sefton properly.’

‘Brief him? It’s hardly a military operation, Father.’

‘Have you exercised, Sefton?’

‘Not this morning, sir, no.’

‘Pity. Never mind. No time now. But in future I’ll expect you to be in fine fettle for our little trips. You’re welcome to use the swimming pool, you know. Down by the orchard.’

‘Thank you.’

‘Not at all. You have a bathing gown?’

‘No, I’m afraid my clothes … I left my luggage on the train.’

‘I see.’ He eyed my blue serge suit with a tailor’s precision, his eyes like tiny chalks.

‘Oh. We’ll have to see what we can do. I think we might have some clothes that fit you. Miriam, do you think?’ They both looked me up and down.

‘About the same height,’ said Miriam.

‘Same build,’ agreed Morley. ‘You know where the clothes are?’

‘Yes, Father.’ Miriam sighed. There was an awkward – and unusual – silence. Miriam poured more coffee, the remains of the coffee from a flask.

‘Anyway,’ said Morley. ‘Bathing suit. I’ll lend you one of mine. Fifty lengths, I’d say? Controlled Interval Method of training I prefer. We need you in tip-top shape. This is not going to be a holiday, you know.’

‘Of course.’

‘So,’ continued Morley, ‘let us set out, shall we, since all our party are assembled, our aims, principles and methods.’

‘Father!’

‘What?’

‘Do give the poor man a break, will you? He’s not had a cup of coffee, and you’re offering him this muck—’ She gestured towards the bowl of oatmeal.

‘Oatmeal.’

‘Muck for breakfast, and he looks like he’s half asleep.’

‘I’m fine, thank you, Miss Morley,’ I spoke up.

‘Oh, good grief, Sefton, come on. Be honest. Tell him. He’s as … as tedious as a tired horse, a railing wife, and worse than a smoky house!’

‘Shakespeare?’ said Morley.

‘Correct!’ said Miriam. ‘Play? Sefton?’

‘Much Ado About Nothing?’ I offered lamely.

‘Henry IV,’ said Miriam, simultaneously sighing and raising her eyebrows – in a manner not unlike her father’s, I would say – as though I had proved the end of civilisation.

‘Part?’ said Morley.

‘What?’ said Miriam.

‘Henry IV part …?’

‘One,’ said Miriam. ‘Obviously.’

‘Correct,’ said Morley. ‘Now, where were we?’

‘Aims, principles—’

‘And methods,’ I said.

‘Exactly. Basic principles first, Sefton. If we’re going to meet our targets we can’t loaf.’

‘No loafing,’ I said.

‘Jolly good. And no funking.’

‘No. Funking,’ said Miriam. ‘Did you hear that, Sefton?’

I ignored her provocation.

‘Do you take a drink?’

‘Well, occasionally—’ I began.

‘And absolutely no drinking while out researching. Have I made myself clear?’

‘Abundantly, Mr Morley,’ I said, scraping the rest of my oatmeal.

‘Good, good. And let’s just remember that procrastination—’

‘Is the thief of time,’ said Miriam wearily, rolling her eyes. ‘I’m going to go and get ready, Father.’

‘Are you not ready already?’

‘In this old thing?’ Miriam smoothed down the sides of her dress, flashing her eyes at me. ‘Now, no man of any consequence would allow me to accompany him on any adventure in this old thing, would they, Mr Sefton?’

‘Erm.’

‘Miriam, please. We need to leave …’ Morley glanced up at a clock on the wall. ‘In forty-seven minutes.’

‘I’ll be ready, Father.’

‘And bring those clothes for Sefton, won’t you?’

‘I shall.’ She sighed again. ‘Now do let Sefton enjoy his breakfast. If enjoy is the right word. Which it is not.’

And with that, she flounced out.

‘I do apologise, Sefton. As I was saying to you last night: animal. Wild animal. Untamed.’

‘Quite, sir.’

‘You don’t drink coffee, do you? Didn’t have you down as a coffee man.’

‘Well, I …’

‘I’ll get cook to make some more.’

‘No, it’s fine. I’ll manage.’

‘Good. Now, where were we?’

‘Aims?’

‘Aims. Precisely. So, aim is, book about once every five weeks. That gives us a chance to get there, gen up on the place, get writing, get back here for the editing. What do you think?’

‘It’s certainly an ambitious—’

‘Though Norfolk I think we can do rather more quickly. Because a lot of it’s already up here.’ He tapped his head. ‘As far as research is concerned we’ll be relying mostly on the archive, Sefton.’

‘The archive?’

‘Yes. Here.’ He tapped his head. ‘Mostly. Archive. From the Greek and Latin for town hall, I think, isn’t it? Is that right?’

‘Probably.’ My Greek and my Latin were not always immediately to hand.

‘Yes. Denoting order, efficiency, completeness. The principles by which we work. We’ll have books with us, of course. But the books are the reserve fund, if you like.’ He smiled and stroked his moustache. ‘Up here, you see, that’s where we do the real work. It’s all about connections, our project, Sefton. Making connections. And you can only make them here.’ He tapped his head again. ‘And context, of course. Context. Very important. Topicality. The topos. Where we find it. You see. If you are digging, you don’t simply make an inventory of the things you discover. You mark the exact location where the treasures are found. Think Howard Carter, Sefton. Another of Norfolk’s sons – make a note. Like Carter we are engaged in a struggle to preserve, Sefton. To find and preserve.’ He checked his watch. ‘Forty-three minutes to departure, Sefton. I have a few things to attend to. You’ll need an overnight bag.’

‘I’m not sure I—’

‘Cook’ll sort you out with something.’ He checked his watch again. ‘Forty-two minutes. See you anon.’

![]()

Forty-two minutes later – or near enough – I made my way outside, where Morley was supervising Miriam packing the car.

‘Forty-five minutes, Sefton,’ he said, without glancing at a watch. ‘Forty-five. Tempus anima rei, eh? Tempus anima rei. You’re putting us behind schedule. Don’t do it again. Now, you’ll be wondering, of course, about method,’ he continued, picking up on the threads of the conversation we’d had forty-five minutes earlier, as though nothing else had intervened between. ‘No, not there, Miriam!’

‘Why, what’s wrong with there?’

‘There,’ he said. ‘Clearly, it fits there.’

Miriam slightly readjusted some bags packed around the large brass-bound travelling trunk that was strapped on the back, numbered ‘No.1’.

‘Do you need a hand at all?’ I said.

‘Forty-five minutes!’ said Miriam mockingly, tightening straps. ‘You have us all behind, Sefton.’

‘You know the word verzetteln, Sefton?’ continued Morley.

‘No, I’m afraid I don’t, sir.’

‘From library science. “To excerpt”. To arrange things into individual slips or the form of a card index.’

‘I see.’

‘Place for everything.’

‘And everything in its place,’ said Miriam, handing me an old Gladstone bag. ‘You’ll be needing these, Sefton.’ The bag was stuffed to overflowing with clothes and dozens of notebooks.

‘Ah. The notebooks,’ said Morley. ‘Jolly good. Notebooks are the fundamental equipment for those who devise things,’ said Morley. ‘Are they not, Miriam?’

‘Yes, Father.’

‘One should always avoid haphazard writing materials, Sefton. Remember that.’

He then gestured towards the car, and daintily climbed into the back seat, whereupon, to my astonishment, Miriam began fitting a wooden desk around him, transforming the rear of the vehicle instantly into a kind of portable office. Safely wedged into his seat, Miriam then hoisted, seemingly from out of nowhere, a small, lightweight typewriter onto a couple of stays on the desk, and stood back to admire her handiwork.

‘Home from home,’ said Morley.

‘Do you like my dress, Sefton?’ said Miriam.

‘Very nice,’ I said, bewildered, as so often in their company. ‘Brown.’

‘It’s “donkey”, actually,’ she said.

‘Donkey? Is that a colour?’

‘Of course it’s a colour. Have you ever seen a donkey?’

‘Yes.’

‘And what colour is it?’

‘It’s—’

‘Donkey is the colour of donkeys, Sefton.’

‘Well—’

‘Enough tittle-tattle, children,’ said Morley. ‘Do we have everything, Miriam?’

‘Yes. Of course. Now, you’ve remembered I’m going to London later, Father?’

‘But—’

‘I told you yesterday. Margaret Whitwell is having a party and she absolutely insists that I’m there. So Sefton will be in charge of things once I’ve dropped you off. Get in, then, Sefton.’

‘Where?’

‘There.’

I clambered into the back with Morley.

‘You know I don’t hold with these London parties, Miriam.’

‘I know that, Father.’

‘I’m just reminding you, that’s all.’

‘Repetition is a form of self-plagiarism, I think you’ll find, Father.’

‘Anyway. We have everything? Pens?’

‘Yes.’

‘Pencils?’

‘Yes.’

‘Koh-i-noor pencils?’

‘Yes, of course.’

‘You use Koh-i-noor, Sefton?’

‘I can’t say that I—’

‘They’re terribly good. Hardtmuth’s. Sounds German. But they’re American. Seventeen degrees. Smooth. Durable. Unsnappable. Four shillings per dozen from my wholesaler. Which isn’t bad for pencil perfection, eh? Notebooks, Miriam?’

‘Yes.’

‘Typewriters?’

‘Yes, of course, Father.’

‘Camera for Sefton?’

‘Yes. Yes. The new Leica.’

‘Good. Portable desk?’

‘Yes. Of course.’

‘Blotting paper?’

‘Yes!’

‘Writing paper.’

‘Yes! Father!’

‘Airmail paper?’

‘Yes, yes, yes. And the elephant rifle, the muskets, the swords, the daggers and the boar spears!’

‘Good.’

‘We don’t really have—’ I began.

‘Of course not!’ said Miriam. ‘But we have everything we need, and now we are going.’

At which, without further ado, Miriam started up the car and set off down the driveway in much the manner she had been driving the day before, which is to say, suicidally. Thrilling at the speed, Morley sat bolt upright, gazing all around like a child, his fingers playing across the keys of his typewriter so much like a pianist about to perform that I almost expected him to play a scale.

‘It’s a Hermes Featherweight,’ he said loudly, leaning across.

‘Very nice,’ I agreed.

‘Nobody else cares about your typewriters, Father!’ called Miriam from the front.

‘Tools of the trade,’ said Morley. ‘Sefton needs to get to know them.’

‘They’re just typewriters!’ said Miriam. ‘Lesson over.’

‘They’re not just typewriters!’ said Morley. ‘Sefton. Look. They’ve only just started manufacturing them. Had it imported from Switzerland. Tremendous craftsmanship.’ He stroked the casing of the machine. ‘I use Good Companions as back-ups,’ he said, ‘but the Swiss do seem to have the upper hand when it comes to precision engineering, don’t you think? Watches and what have you.’ He held up both wrists to me – a watch on each wrist. ‘Luminous dial,’ he said, pointing with his right hand to his left wrist, and then pointing to the right wrist, ‘And non-luminous dial.’

‘Super,’ I said.

‘Beautiful, isn’t she?’ continued Morley, addressing the typewriter.

‘She’s certainly a very nice typewriter,’ I said.

‘And incredibly light. Here.’ He pulled the typewriter towards him, removed it from its wooden stays and handed it across to me.

‘Extraordinary, isn’t she?’

‘It’s certainly very light.’

‘Eight pounds.’

‘Very light.’

‘You could sit her on your lap almost, couldn’t you? Never mind portables, Sefton. Lapwriters, that’ll be the next thing, mark my word. Five, ten years, we’ll have typewriters you can fit into your pocket!’ He was always coming up with absurd predictions about machines of the future – he corresponded, of course, for many years with H.G. Wells about the nature and practicalities of time travel – and there was also his famous shed, more like a barn, at St George’s, mentioned by all the biographers, and which contained the carcasses of many engines, clocks and bicycles, the mechanisms of which he was continually seeking to improve, or, more likely, confuse: there were clocks made from bicycle parts, and bicycles made from clock parts. The story of Morley’s ill-fated steam-paraffin-driven bicycle I shan’t repeat here, for we were sweeping out onto the open road, and I was having trouble keeping up with the briefing …

‘So, that’s me,’ he said, wedging the typewriter back into position. ‘You, meanwhile, will mostly be using the notebooks. Have them imported specially from Germany. The very best. Waterproof.’

I picked up one of the notebooks from the bag Miriam had handed me. And it was indeed a fine notebook: octavo, morocco-bound, lined, with a red ribbon marker dangling from it, like a fuse.

‘Feel the heft of it,’ said Morley.

I weighed the notebook in my hand.

‘Beautiful, isn’t it?’ he said.

‘Yes, again, it’s quite … beautiful,’ I said. I had never before met a man who cared so much about his writing equipment. I had always managed to get by with pencils and the backs of envelopes and cigarette packets.

‘Leave the poor man alone!’ cried Miriam from the front. ‘Nobody wants to hear about your stationery fetish.’

‘My what?’ said Morley.

Miriam groaned. ‘Never mind.’

‘My advice to novice writers when they write to me, Sefton, is very simple. “Avoid haphazard writing habits. And haphazard writing materials.” And that’s it.’

‘That’s it?’ I said.

‘That’s it,’ agreed Miriam, from the seat in front.

‘That’s it,’ said Morley. ‘That is the secret of my success.’

In fact, as his own notebooks clearly show, Morley’s work was forever verging on the haphazard, with sketches, diagrams, coordinates and figures of all sorts crowding the pages, not to mention the words themselves. He wrote – as anyone familiar with the biographies will know – not only continuously and prodigiously, and in the same notebooks for almost forty years, but also in a tiny, lunatic hand. Indeed, over the years of our relationship, his handwriting became progressively smaller and smaller, almost to the point of being unreadable except by the use of a magnifying glass. His stated ambition was to squeeze ina hundred lines per page. Sometimes, pausing in between his labours, I would notice him counting the lines, again and again.

‘Blast it!’ he would say.

‘A problem, Mr Morley?’

‘Ninety. Blast it.’

‘Ninety?’

‘Lines.’

‘Ah.’

There was, I came to realise, a relationship between the size and density of his writing and his lavishness of aim and ambition in wishing to capture reality as he felt it existed: it was as if by making things small he also somehow emphasised their magnitude and significance. I, on the other hand, averaged at best twenty lines a page. Which he believed to be a sign of moral turpitude.

‘Now. Norfolk. Norfolk. What do you think of, Sefton, when you think of Norfolk?’

‘“Very flat, Norfolk”?’ I said, regretting it immediately.

Morley groaned as though I had prodded him in the side with a spear. ‘Spare us the Noël Coward, Sefton, please. Terribly overrated. Not a fan. Poor man’s Oscar Wilde. Who was himself, of course, the poor man’s Dr Johnson. Who one might say was the poor man’s Aubrey. Who was the poor man’s Burton … Who was … Anyway … A quip is not an insight, Sefton. And besides, it’s not, actually, Norfolk.’

‘What?’ I did my best to keep up.

‘Flat. Ever been to Gas Hill, in Norwich?’

‘No, I—’

‘Precisely. West Runton? Beacon Hill?’

‘Again, no, I—’

‘There you are, then. It’s actually made up of three very distinct geological areas, Norfolk.’ He made cupping movements with his hands, as though the entire county was within his grasp. ‘Flatlands in the west. Chalklands and heathlands of the north and the centre. And the rich valleys of the south and east.’

‘I see.’

‘From which we might learn much about the history of the place. “Very flat, Norfolk!” Worthless. Ignorant. Stupid. We can learn everything about a place from its landscape, Sefton, if we bother to pay attention to it. You’re going to have to clear your mind of cant, if you wouldn’t mind, when we’re discussing these things. I want to know what you think when you think of Norfolk, Sefton, not Mr Know-All Coward. Independent thought, Sefton. That’s the thing. The mind unshackled. So. Let’s try again, shall we? When I think of Norfolk I think of …’

‘When I think of Norfolk I think of—’

‘Churches. Exactly. Very important. Beguiling county of great religious art and culture.’

‘I see.’

‘Write it down, Sefton.’

And so I took up a pen and began to write; my first notes of our grand project.

‘Saxons, Normans, came, built their churches. Churches. That’s the way in to Norfolk. Not a lot you can’t learn from churches. Norfolk has some six hundred medieval churches, I think. Check that. Most of them of the Perpendicular.’ He pulled a piece of paper from a pocket. ‘Here. I have a little list.’ He brandished a scribbled list. I read it. It was a list of churches: three columns per side, one hundred lines apiece.

‘There’s certainly a lot there,’ I said.

‘Six hundred,’ he said.

‘Yes, that’s a lot.’

‘Don’t worry, Sefton. We’re not going to visit them all.’

‘Right. Good.’

‘Four or five hundred should do us. I thought we’d start with the churches. Get them out of the way. And then we’ve got all of Norwich to do. Carrow Road. “Come on, the Canaries!” Though I’m not a great fan of association football. And I thought we might do something on the speedway at Hellesdon – terribly popular, you know, speedway. Are you a fan, Sefton?’

‘I can’t say—’

‘And then something on the flora and fauna – lavender and what have you. And Thetford Forest, I suppose. Largest lowland pine forest in Britain, I think I’m right in saying, though we’ll have to check, of course.’

Norfolk, county of mills

‘Of course.’

‘And all the little curiosities: Whalebone House in Cley. And the windmills and the water mills. Brick mills. Drainage mills. County of mills, Norfolk. And some of the modern industries, of course – we mustn’t forget Colman’s. But the churches first. Need to get our priorities right, eh?’

‘Yes.’

‘Definitely Trunch.’

‘Trunch?’

‘You know the font canopy at Trunch?’

‘I can’t say I do—’

He sniffed the air, as though he could actually smell the font canopy at Trunch, like the lure of wild game beckoning to him across the East Anglian tundra.

‘And Ranworth,’ he said. ‘Wonderful. And the crypt at Brisley – used for prisoners on their way to the Norwich jail, did you know?’

‘No, I can’t say I—’

‘The Labours of the Month at Burnham Deepdale. Early Gothic leaf carving at West Walton, curvilinear windows at Cley and at Walsingham. Oh, yes. It’s going to be a wonderful few days, Sefton. All on the list there, if you look.’

I stared at the list as Morley continued to recite the wonders of many of Norfolk’s six hundred churches, and Miriam kept gunning the engine.

‘… the hammerbeam roof at Cawston, the giant St Nicholas in Yarmouth, the Seven Sacraments font at Dereham, the four great churches of Wiggenhall …’

We paused briefly, and thankfully, at a crossroads, Morley and engine idling.

‘All sounds fas-cin-ating,’ yelled Miriam from the front, yawning loudly.

‘Yes, I think it will be.’

‘I was being ironical, Father.’

‘Oh? Were you? I do wish you wouldn’t, Miriam. It’s terribly bad manners.’

‘It’s the height of sophistication, actually.’

‘Really? Sefton?’

‘Sorry, Mr Morley?’

‘Irony?’

‘What about it, Mr Morley?’

‘An adjudication, if you please?’

‘On?’

‘Irony. Good thing, or a bad thing? What do you think?’

‘It certainly shows a certain … detachment,’ I said. ‘And an energy of response.’

‘Energy of response,’ he said. ‘I like that. Very nice, Sefton. That’s why we’ve hired you. He admires your energy of response,’ he called out loudly to Miriam.

‘Really?’ said Miriam. ‘I’m flattered, Sefton. I shan’t return the compliment, though, thank you. Now, which way?’

‘Left,’ said Morley.

Miriam swung the vehicle left, and we began to pick up speed.

‘Anyway,’ said Morley, tapping at the keys, with one eye on the surroundings. ‘Ah!’ he cried. ‘Notable roof!’

‘Sorry, Mr Morley?’

‘A notable roof. There. See?’

He pointed towards what looked like an entirely average Norfolk roof of blackish-red pantiles.

‘See?’

‘Yes,’ I said.

‘Make a note,’ said Morley.

I wrote down the words ‘Notable roof’.

‘Sorry, Mr Morley, notable in what sense?’

‘Blackish tinge around the chimney?’ he said.

I turned and looked behind me as the house and its chimney vanished into the distance.

‘Yes.’ The chimney was indeed blackened.

‘And what make you of that?’

‘I don’t know.’

‘And he doesn’t care!’ cried Miriam.

‘Don’t care was made to care,’ said Morley. ‘And don’t know isn’t an answer.’

‘Yes it is!’ said Miriam.

‘A chimney fire, perhaps?’ I said.

‘Oh, come on. Go for the obvious answer first, Sefton, shouldn’t you? Before indulging in fantasies? A blackened chimney? Logical explanation? Primary cause?’

‘A hot fire?’

‘Aha! Exactly. And why would this particular house, among all the other houses in the village, have such a hot fire, do you think?’

‘Because the inhabitants are colder than the others?’

‘Possible, I suppose. Except that we know nothing of the inhabitants. Context?’

‘A house in a village?’

‘Correct. And moreover?’

‘Erm …’

‘A house in the middle of a village. Significant, surely? Small village, house centrally located, with blackened chimney, suggesting hot fire, suggesting …’

‘I’m afraid I don’t know, Mr Morley.’ I was rather exhausted from his mental exertions.

‘What about a little one-man bakery, Sefton? No market here for bakers’ vans from the town, or your Woolworth’s.’

‘Ah.’

‘The baker’s house, I’d warrant.’

‘I see.’

‘And there’s the peep of history, you see, Sefton! By studying the small things we might be able to understand the larger things. As a leaf will tell us about a tree, and a rivulet about the river, and the minute reveals the day, and—’

‘Yes, all right, Father, we get the picture.’

‘People have come far too much to rely on the far-off voices of Savoy Hill, Sefton, in my opinion. We need to use our own eyes, Sefton. And own ears. This is our England that’s disappearing, Sefton, right around us. The granary of England, Sefton. Destroyed by our mania for shop-bought bread.’ He stared across at me. ‘You look like a man who eats shop-bought bread.’

‘I suppose I am, Mr Morley, yes. Or, I mean, I have eaten—’

‘That’ll be a section in the book, Sefton. The Granary of England. Against Shop-Bought Bread. Make a note.’

I made a note.

The journey continued in like manner, with Morley variously interpreting the landscape and growing overcome with a sense of wonder at the world, while I made notes: lime trees; ash woods; sea-lavender; seals; squirrels; snakes; the history of flint-knapping. Idling at another junction, over the roar of the engine, we could just about hear the sound of birdsong.

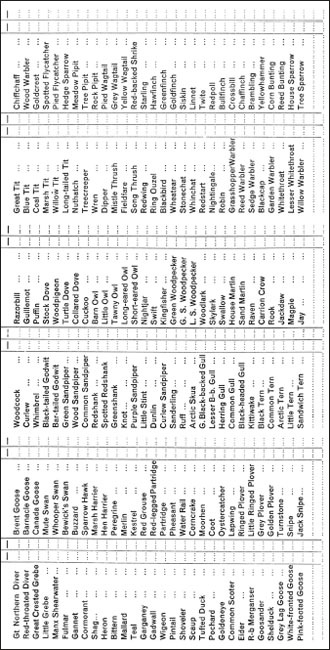

From Morley’s Field List of British Birds (Simplified)

‘Birds, Sefton.’

‘Yes,’ I agreed, feeling on reasonably solid ground.

‘Recognise them?’

‘Ah.’ I had never learned birdsong.

Morley repeated the noises himself. ‘Now, what’s that, Sefton?’

‘I’m afraid I don’t know, Mr Morley.’

‘Have you no idea at all, man?’

‘I’m afraid not.’

‘Well, hie ye and buy a bird book. Hie ye and buy a bird book. Snipe, sandpiper. And the wonderful song of the thrush,’ cried Morley. ‘Or the mavis, of course, as he is called hereabouts. Ah! The local names of birds – make a note, Sefton. Worth a little list in our book, isn’t it? Hedgeman for the sparrow, ulf for the greenfinch. Are you familiar with them?’

I confessed that I was not.

‘We’ll include a little checklist, shall we, in the County Guides? For bird-spotters? What do you think?’

‘I think it’s—’

‘Spink, I think, is the local term for a chaffinch, isn’t it? Miriam?’ he shouted.

‘What?’ she yelled back from the front.

‘Spink?’

‘What?’

‘Spink!’ yelled Morley.

Miriam glanced around at me. ‘Sorry, Father, I misheard you.’

‘Which reminds me,’ continued Morley, on another of his detours, ‘there’s a man in Great Yarmouth who claims to be able to speak seagull language. Make a note, Sefton. We must remember to call in on him.’ I made a note, and Morley began to sing: ‘“He sings each song twice o’er, / Lest you should think he never could recapture / The first fine careless rapture.” Good omen, isn’t it? The song of the thrush. Let’s on in careless rapture, shall we? To Blakeney!’

I glanced at my watch. It wasn’t yet nine o’clock in the morning. It had already been a long day.