OUR ADVENTURE PROPER BEGAN, as all adventures begin – as Morley himself might say – in media res.

We arrived at the old seaport of Blakeney, the song of the thrush preceding us, by nine o’clock, exactly according to schedule. Unscheduled, however, were the vast cloud shadows and the creeping fog that came upon us as we arrived. I had never before travelled in Norfolk and was struck immediately by the remarkable combination of vast golden fields, green trees, wide never-ending skies, the flatlands and the fog, creating the illusion of a vast oasis in a desert. I mentioned it to Morley.

‘Very good,’ he said. ‘Make a note. Just the thing we’re after. Norfolk: an oasis.’ He was given always to such phrases – summings-up, gists and piths. His goal was always ‘the telling fact’. ‘The telling fact,’ he would sometimes murmur to himself, searching for it among the lumber of his mind. ‘All we need here, Sefton, is the telling fact.’ It was the legacy, I suppose, of so many years spent as a journalist and editor: he thought in captions and headlines. ‘Minimum words. Maximum information,’ was one of his many mottoes. ‘Cacoethes loquendi, cacoethes scribendi,’ was another. He was a man of contradictions.

We had travelled – at accelerating speed, which seemed to thrill Morley almost as much as his daughter – on the winding road from Cley, over the bridge across the River Glaven.

‘Note,’ cried Morley, in full flow, ‘there are three great rivers in Norfolk: the Great Ouse, the Yare and Stiffkey. Among the smaller rivers and tributaries the most beautiful is perhaps the Glaven, which rises in Bodham and flows down to Blakeney Point, through the majestic mills and quiet ponds of the lower Glaven valley.’ He paused for breath, as I hurried to note it down. ‘Too touristy?’ he said.

‘Well, it is perhaps—’ I began, but he had already passed on to his next observation.

‘Wiveton Hall, majestic, halfway ’twixt the church and shore. And then the quaint charm of Blakeney, the name possibly derived from the Scandinavian, Blekinge in Sweden. Others say the name derives from the Black Island, the finger of land we know as …’

It felt like being dragged into the wheels of some kind of endless writing machine.

‘Am I speaking too fast for you, Sefton?’ he would sometimes ask.

‘Perhaps a little fast, Mr Morley,’ I would say.

‘I’ll slow down then, shall I?’

‘Please,’ I would say. And he’d slow down – for about a minute. And then he’d be off again: the crow-stepped gables on the houses; the cry of the bittern; the history of flint-tipped arrows. The entire duration of our trip – as on every trip – he perched high in the back of the car, the typewriter across his lap, tap, tap, tapping away, dictating to me, and glancing around continually at the scenery for all the world like a bird seeking where it might find to make its nest.

Blakeney: the Florence of East Anglia

The soft, grey morning fog was borne in from the sea, muffling Blakeney in silence as we drove down to the quay, swaddling and concealing the village from us as though a mother were wrapping it tight in a blanket of muted grey-blues and grey-gold. The place seemed not yet to have come awake – or to have come awake many hours ago, and left to go to work – and we drove through narrow, deserted streets. Out across the mudflats there were only wading birds, and a few walkers.

‘Holidaymakers,’ pronounced Morley decisively as we parked at the quay.

‘Oh, Father, how can you tell from this distance?’

‘Distance is hardly the problem, I think, Miriam.’ Morley consulted his watch. ‘Time, not space, my dear.’

‘Meaning?’

He consulted his watch. ‘Nine ten a.m. Two people out walking. What does that suggest?’

‘They could be going to work.’

‘With a walking stick?’

‘They might have a bad leg?’

‘Clearly not,’ said Morley, peering after the disappearing shapes.

‘Fishermen?’

‘In grey mackintoshes and gum boots?’

‘Oh, whatever,’ said Miriam, yanking on the handbrake.

Morley carefully levered himself from his seat, and then climbed down from the car, and sniffed the air.

‘Great day!’ he announced.

‘No. It is not a great day. It is a grey day, Father,’ said Miriam. ‘Grey, foggy, and—’

‘If there’s enough blue to make—’

‘A pair of sailor’s trousers—’

‘Is what I always say.’

‘We know,’ said Miriam.

‘Gamey, isn’t it?’ continued Morley, sniffing again, while I scrambled after him as he began to stroll purposefully past the deserted pleasure boats along the quay. ‘Muttony, almost. Reasty. Wouldn’t you say? Make a note, Sefton. Blakeney. Reasty. Do you know the word?’

‘No.’

‘Hmm. Sometimes said of bacon. But it’ll do us here, don’t you think?’

I took a sniff.

‘Smell of the tidal estuary,’ continued Morley. ‘Yeasty. Rank. Gamey. Yes?’

‘Something rotten in the state of Denmark,’ I ventured.

‘Strictly speaking, I think the Bard is referring to something rotten in the body politic at that point, Sefton. The smell here is simply a smell. We shouldn’t get carried away with ourselves, should we? Now, camera. Miriam?’

Miriam duly produced the camera from one of the trunks and proceeded to give me a basic lesson while Morley offered a brief history on the development of photography.

‘It’s the innovations in shutter speed and focal planes that makes them now so light, of course; and as for our Leica D.R.P. Ernst Leitz Wetzlar IIIa here … Best that money can buy, Sefton. Always worth getting the right kit, isn’t it, Miriam?’

‘True, O King!’

‘I do wish you wouldn’t say that, Miriam.’

‘Why? That’s the response he’s looking for, Sefton. You might as well get used to it. Book of Daniel,’ she said.

‘Chapter three, verse twenty-four,’ added Morley. ‘Do you remember your first 35mm, Miriam?’

‘I do, Father, indeed.’ She glanced at me again.

‘The Coronet?’

‘Yes. Nice camera.’

‘And before that, what was it?’

‘A Contax, Father. And a Rolleiflex roll-film, that was rather fun.’

‘Yes, of course. Anyway, all set? Got the gist of it, Sefton?’

‘Say “Yes, O King,”’ said Miriam.

‘Yes, Mr Morley.’ I seemed as prepared as I was ever going to be.

‘You know the work of Gisèle Freund?’ he asked, striding ahead.

‘I’m not sure—’

‘Life magazine.’

‘No, I don’t think I—’

‘Anyway, that’s not what we want. I’m thinking more Cartier Bresson, Brassai, Sefton. You know the sort of thing.’

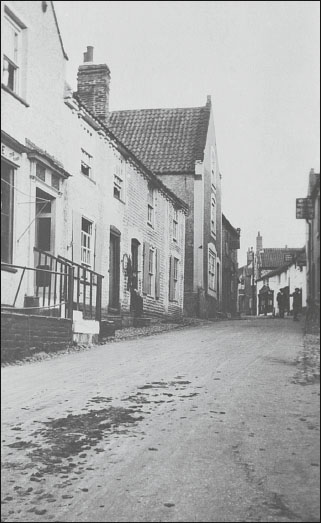

I did not know the sort of thing, but agreed, and began making notes and taking photographs as instructed. It took me a while to get the hang of the thing, but eventually I seemed to work it out and started snapping away: the old Guildhall; detail of some of the fine Flemish brickwork; the little red-roofed cobble cottages jammed together among the boat sheds and alleyways. Instantly I liked the feel of the camera in my hands. It felt like a form of protection. Morley, meanwhile, continued composing aloud, on the hoof, as it were, adding captions to the photographs as quick – and often quicker – as I was taking them.

‘The town, with its little red-roofed cobble cottages. Marvellous, aren’t they, Sefton? The pantiled dormers, with their gentle slopes like the curves … like the curves of a woman’s body, eh? Actually, strike that, Sefton. Do you know the domes of Burma and India?’

‘Not personally, Mr Morley, no.’

‘Things of incomparable beauty. I’m a great fan of Indian architecture. All that copper and gold on the temples and the mosques. Sort of oriental versions of the roof of Westminster Hall, I always think. Don’t you?’ I did not answer: it did not matter. ‘Which of course – I think – is the biggest oak roof of its kind in England. We’ll need to check that. Timbers fashioned from oak which were saplings when the Romans ruled the land.’ He glanced at the roofs around him. ‘But these? They are like an Italianate city. Italianate, wouldn’t you say, Sefton? The alleyways and what have you?’

‘Yes.’

‘Florentine,’ he mused. ‘Yes. There we are. “Blakeney: The Florence of East Anglia.” That’ll do. Make a note.’ And on. And on.

![]()

Miriam soon made her excuses and took herself off to the Blakeney Hotel down on the quayside, where, she informed us, she hoped to procure coffee, smoke cigarettes and, if at all possible, scandalise the natives – an objective, I fancied, that might not take more than a quarter of an hour. Morley and I meanwhile walked up through the streets, bidding good morning to the occasional passer-by, Morley noting both out loud and in his notebook some of the more notable roofs, gables and architectural features that took his fancy. Eventually we made it to the top of the village, a slight breeze coming up behind us, splitting the fog, and a church rising before us like a …

‘Galleon on the high seas,’ said Morley, who as usual was several steps ahead.

As we approached the church I noticed a pair of owls were busy around an old alder.

‘Owls,’ said Morley. ‘Note.’ Which I already had. ‘And the arched roofs of the alder, gabled like porches,’ he added. Which I had not. He was always able to find and describe the unexpected, even among the unexpected. ‘And so, Sefton,’ he continued, striding through the graveyard, spreading his hands before him as if introducing a fairground attraction, or a troupe of music-hall performers, ‘as if coming to announce itself to us: the mystery of the church at Blakeney.’

‘The mystery?’

‘Indeed.’ He stopped in his tracks and turned to face me, the church looming behind him. ‘There is mystery all about us, Sefton, if only we would open our eyes and perceive it. Is this not the lesson taught to us by all the great mystics?’

‘Perhaps,’ I agreed.

‘Look at these headstones, for example. Hundreds and hundreds. And each one with a story to tell if only we would let them tell it, eh?’ He knelt down by a gravestone. ‘The joie de vivre of the English stonemason, Sefton. Quite extraordinary. Humbling.’ He traced the words on the stone with his fingers. ‘Traditional English letter forms, Sefton. Quite unlike their continental counterparts: bolder strokes, thinner strokes; the abrupt transition from thick to thin. See? Inspiring, isn’t it?’

‘Yes,’ I said, trying to sound inspired.

He stood up. ‘Now, what is it that strikes you about the church, Sefton?’

I gazed up at what appeared to me to be simply … a church. A faded board outside announced that it was St Nicholas, Blakeney, with service times at 8 a.m., 10 a.m.,4 p.m. and 6 p.m. on Sundays and matins during the week.

‘A typical example,’ Morley continued. ‘I would say – wouldn’t you say, Sefton? – of fifteenth-century Perpendicular architecture. Though of course with one very peculiar and distinguishing feature.’ He paused. ‘Which is?’

I gazed along from the west tower to the—

‘Two towers,’ he exclaimed.

‘Ah.’

‘Indeed. Like an aft-mast and a main mast, aren’t they?’

I agreed that indeed they were.

‘Now, note, Sefton.’ I took out my notebook and began to write. ‘The chancel tower, the east tower, is believed by many to have been a lighthouse.’

‘Really?’

‘Yes. But does it look like a lighthouse to you, Sefton?’

I looked up again. ‘It could be a lighthouse, I suppose.’

‘Hmm. But what is it lacking, would you say, in its potential capacity as a lighthouse?’

‘Lights?’ I suggested.

‘Of course. But it is not night. And even now without, lights it once might have had. Lights there may have been.’ He pointed up to the top of the tower. ‘So, the lack of lights, we are agreed, is hardly a sufficient reason for what we suspect to have once been a lighthouse indeed to have been such. Is that correct?’

The mystery of the church at Blakeney

‘I suppose.’

‘Good. So, to return to the question: what is the other essential condition of a lighthouse functioning as a lighthouse, Sefton? Not only light, but …’

‘I’m sorry, I don’t know.’

‘Think about it.’

‘Sorry, I don’t—’

‘Don’t give up! A lighthouse needs …’ He stood on his tiptoes, and stretched his hands high above his head.

‘Height?’ I said.

‘Height!’ said Morley. ‘Exactly! Yes! Indeed. There we are. So if you were building a lighthouse, might you not have made the east tower here a taller tower?’

‘Yes, I suppose I would,’ I agreed.

‘Or simply installed your light in the west, the taller tower, which clearly predates the other?’ The west, taller tower, I could confirm, looked older.

‘So why didn’t they make it taller?’

‘You see, you see. That, Sefton, is the mystery of the church at Blakeney. Make a note now. Come, come. Let’s venture in.’

But just as I was about to write down this latest insight, a woman came rushing out of the church and out of the fog towards us, like a wraith or a demon.

‘Oh! Oh!’ she cried when she saw us, grabbing hold of Morley’s arm. ‘Oh, oh!’ she continued to wail.

‘What seems to be the problem?’ said Morley. ‘Madam. Are you all right?’

The woman had the look about her of someone who was not at all all right, and who was indeed so not all right that she was about to collapse and become very un-all right indeed. Sensing that this might be the case, Morley promptly produced a bottle of smelling salts from his waistcoat pocket; he never travelled without it, regarding it as an essential pick-me-up. (If I ever saw him begin to fade – and it happened, perhaps, no more than half a dozen times during the course of our long association – he would instantly produce the smelling salts, take a sniff, and straight away be off again to a fresh start.)

‘The reverend … is …’ the woman began, momentarily revived by the first whiff of the smelling salts. But she was unable to finish the sentence, as if caught by the throat by an invisible hand.

‘Yes?’ said Morley, waving the bottle now more vigorously beneath her nose.

The woman took in deep breaths, and again the smelling salts seemed to have a momentary effect.

‘The reverend … He’s …’ But again she seemed about to go under.

‘Goodness,’ said Morley, taking the woman gently by the arm. ‘A three-sniff problem, Sefton,’ he said to me. ‘Come and sit down here,’ he instructed the woman, brushing some moss from a gravestone – Arthur Cooke, Surgeon of Addenbrooke’s Hospital, Cambridge, 1868–1933, R.I.P. He set her gently down. ‘There. I’m sure Mr Cooke won’t mind.’

The woman looked dazed.

‘Now. Are you sick?’ asked Morley. ‘Unwell?’

‘No. No. The reverend.’

‘He’s sick?’

‘He’s not sick, no!’ the woman said, before losing the power of words again. ‘He’s …’ She pointed towards the door of the church.

‘Yes, you said. Now what’s your name, my dear?’ asked Morley.

‘Snatchfold,’ she said. ‘Snatchfold.’

‘Right, well. If you can tell us what’s wrong, Mrs Snatchfold, we might be able to help.’

‘He’s …’

Mrs Snatchfold was clearly going to be unable to tell us anything further.

‘Well, how about we go and see the reverend, shall we?’ said Morley, taking charge of the situation. ‘Is he here in the church?’

‘Yes, yes. In the church.’

‘Very well. Come on, Sefton. Something’s up. Let’s not dilly-dally. Would you rather stay here, my dear?’

‘No!’ she said. ‘Don’t leave me!’ At which she sprang up from her sitting position and held on tight to Morley’s arm.

‘Very well, then,’ said Morley, glancing at me, perturbed. ‘Clearly a serious business. Lead on.’

As she led us into the church I was surprised to see another woman, standing by the font, her hands folded, almost in the pose of Mary at the foot of the Cross. She had her back to us.

‘Hannah,’ said Mrs Snatchfold. ‘This is Mr …’

‘Morley,’ said Morley. ‘Swanton Morley.’

‘And I’m Sefton,’ I said. ‘Stephen Sefton.’

‘Hello,’ said Hannah, who did not turn fully towards us, but merely looked over her shoulder, as if in fear or contempt. She seemed about to speak further, but then thought better of it and bit her lip. She nodded towards the altar.

Mrs Snatchfold led us through the nave. The church was much larger than I had expected, almost a small cathedral, and Morley, even in the midst of this unexpected adventure, could not help himself from remarking as he went. ‘Ah yes,’ he said, rubbing his hands together, speaking only to himself, ‘font, octagonal; nave – one, two, three, four, five, six bays; chancel with a rib vault; seven-lancet east window; grand Victorian pulpit; extraordinary rood screen; angels up in the hammerbeam, I think; and Nativity figures, altar … Oh.’

We had duly proceeded into the chancel at the east end of the church, and then through a curtain by the altar, up a steep, tight spiral staircase, and into a room where we discovered the cause of Mrs Snatchfold’s distress.

The reverend was hanging by the neck from a bell-rope, his features horribly distorted, his face staring up at nothingness, his lips pulled back in a grimace – an expression that Morley later remarked reminded him of a Barbary ape that he had once seen on his travels in the Atlas Mountains. A trail of phlegm-like liquid stained the front of his dog collar. Mrs Snatchfold stood by the door, shaking, but Morley strode towards the dangling body, peered at it, removed his spectacles, glanced around the room, andpeered again.

‘Is he … dead?’ asked Mrs Snatchfold fearfully.

‘I think we can safely assume so, madam, from the evidence,’ said Morley. ‘What do you think, Sefton?’

I had stayed unwittingly by the door myself, not so much from fear but from surprise. I had seen so much of death in Spain, but this was in some way much worse: it was the incongruity. Morley waved me forward.

‘Come, come, second opinion please. Sefton. Quickly.’

I stepped forward.

‘Dead?’ said Morley.

I nodded.

Nonetheless, Morley reached up and tried to find a pulse on the reverend’s wrist. There was nothing.

‘Skin still warm,’ Morley said, stepping back and standing up straight. ‘What do you think? Suicide?’

Mrs Snatchfold gave out another wail, and then promptly fainted. I rushed over towards her.

‘Leave her,’ commanded Morley, not turning round.

‘But, what about the smelling salts?’

‘What about them?’

‘Shouldn’t we—’

‘You’ve never seen a woman faint before?’

‘Yes, but …’

‘Yes but nothing, Sefton. We’ve got work to do. Come on, we need to move fast and take notes while the scene is fresh. Priorities, Sefton. We have a dead body here. We can deal with our fainting lady in due course.’

Morley had already produced one of his German notebooks from his jacket pocket and was surveying the scene. He leaned forward and sniffed at the chalice on the table, touched the back of his fingers to the side of it. He consulted the time on his pocket-watch. Consulted the time on his wristwatch. And his other wristwatch. Scribbled something in his notebook. Then he turned his eyes from the body, looking carefully around the rest of the room, his eyes roaming over every detail, taking careful note of what he saw.

‘Note?’ he said.

‘Sorry?’ I assumed he wanted me to make a note.

‘Any sign of a suicide note?’

‘Not that I can see,’ I said.

‘No,’ said Morley. ‘There rarely is. Never mind.’

There was the sound of Mrs Snatchfold stirring.

I began to go over to assist her up.

‘Leave her,’ said Morley. ‘You’re fine, Mrs Snatchfold,’ he called across to her, continuing to make notes. ‘You’ve simply fainted, that’s all.’

‘Oh, I’m sorry,’ said a tearful Mrs Snatchfold weakly from the floor, ‘it’s just …’

‘No need to apologise,’ said Morley. ‘Tell me, have you called the police?’

‘Yes. I sent a boy over to the rectory, sir. There’s a telephone there.’

‘Good. You did the right thing.’

Mrs Snatchfold lay, staring at the reverend’s body. ‘What’s that smell?’ she said.

‘He’s evacuated his bowels, I’m afraid, Mrs Snatchfold. Very common, I believe, in such cases. This stain here …’ He moved over towards the table and began pointing to the various stains.

Mrs Snatchfold gave another small cry, and fainted again.

‘Leave her, Sefton,’ he said once more as I went to assist. ‘Leica.’

‘What?’

‘The camera, man. You’ve got it?’

‘Yes.’ I brandished the camera.

‘Good. Well. Go on. Some photographs.’

‘Of the church?’ I was shocked. This hardly seemed the time to be working on the book.

‘No, not the church, man. Here. This.’ He gestured at the body, and the room.

‘Here?’

‘Yes.’

‘Isn’t that a bit macabre?’

‘This could be a scene of crime, Sefton. Corpus delicti.’

‘I hardly think—’

‘Come in useful, anyway,’ said Morley. ‘Before the police arrive and make a mess of things. Come on. Snap, snap. Just for our own records.’

I took a series of photographs while Morley strode around the room, stepping carefully over Mrs Snatchfold’s prone form, making copious notes and talking the whole time.

‘Many as you like, Sefton. Come on. Chop, chop. This, please. Photo.’ He pointed to a small coat of arms mounted on the wall. ‘Zelo Zelatus sum pro Domino Dio exercitum. Translation, Sefton?’ I couldn’t come up with a convincing reading. ‘Look,’ said Morley, pointing beneath the words. ‘Tells us the verse, for those of us without the Latin: 1 Kings 19:14. Any idea?’

‘No.’ But then, as Morley turned away to study some of the books on the shelves, and thinking I was doing the right thing, I put down the camera, picked up the Bible that lay on the table at the reverend’s feet, and was about to flick through to 1 Kings 19:14 when Morley turned.

‘No!’ he said.

I stopped, about to turn the page.

‘Don’t move!’ said Morley.

‘What?’ I said. ‘Why?’

He removed the Bible carefully from my hands, looked at the page where it was open, and made a note in his notebook. ‘Photograph,’ he said, waving at the page. ‘Please.’

‘Of the Bible?’

‘Of course.’

‘Why?’

‘What’s the passage it’s at?’

I looked down at the Bible. ‘Judges chapter 16.’

‘And do we know if that is the lesson for today?’

‘I don’t know. Does it matter?’

‘It might, Sefton. Or of course it might not.’

‘Right,’ I said.

‘Carry on,’ said Morley. ‘Chop, chop. Snap, snap, snap.’

When I had taken sufficient photographs to satisfy Morley’s needs – which were many – and Mrs Snatchfold had sufficiently revived, Morley ushered us both back towards the stairs.

‘No point upsetting ourselves further here. Clearly a matter for the police. I’m sure they’ll be here soon. Why don’t you wait outside, Mrs Snatchfold. You wouldn’t want to distress yourself further.’ At the top of the stairs he whispered to me, ‘You first, Sefton. In case we need to break a fall.’

We made it safely without incident back through the church. The woman who Mrs Snatchfold had introduced to us as Hannah stood inside the porch, and as we approached I saw her reach into her pocket for a cigarette and light it. She pulled in a deep breath of smoke.

‘Would you mind?’ I asked.

‘Of course,’ she said, and offered me a cigarette, surveying me carefully as she did so. There was something shockingly direct and frank about her gaze. It was chilling. I could think of nothing to say.

‘So?’ she said.

‘He’s dead.’

‘Of course,’ she said, and gave a little laugh.