WE PUT UP IN THE BLAKENEY HOTEL. Miriam had long since departed for London. After a light supper we adjourned to the hotel’s public bar. Morley always insisted on the public bar, believing saloon bars to be places of ill-repute. ‘Strictly for duchesses, cads and travelling salesmen,’ he would say. ‘And hoity-toits like you, of course, Sefton.’

The bar was busy: locals. The ritualistic sound of pint glasses, and of low, muddy, murmuring Norfolk voices. And then there was the sound of Morley, cutting through.

‘“Set ’em up, Joe,”’ he said, unfortunately, to the barman.

‘I beg your pardon, sir?’

‘I said, “Set ’em up, Joe.”’

You could hear men squint, and the sound of calloused hands being rubbed.

Morley, as everyone knows, had a predilection for reciting nursery rhymes, and tongue-twisters, and indulging in verbal games of all sorts – it was the flipside, I suppose one might say, of his fluency, an aspect of his character much remarked upon and cherished; another sign of his droll English eccentricity. His habit of imitating phrases from American films and novels, however, and often at the most inopportune moments, was one of his lesser known and less endearing characteristics.

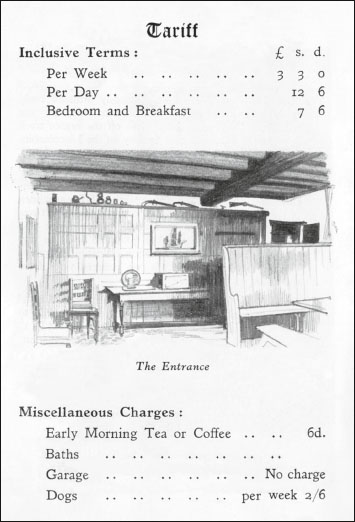

Tariff from the Blakeney Hotel

‘What can I get you, sir?’ said the barman stoically.

‘“Set ’em up, Joe!”’ Morley said again, rolling the phrase around in his mouth. ‘Extraordinary phrase, isn’t it? I don’t know if you’re a fan of the Western?’

‘No.’

In the public bar of the Blakeney Hotel that evening, it suddenly felt like a Western, and we were the unwelcome strangers just ridden into town.

‘No? The Texas Rangers? Custer’s Last Stand? Gene Autry, the Singing Cowboy? “Mexicali Rose”? “Mexicali Rose, stop crying—”’

I stepped in quickly before Morley got into the swing of his cowboy singing.

‘A pint of beer for me, please.’ Morley looked at me disapprovingly. ‘Under the circumstances,’ I said.

‘Very well,’ said Morley.

‘And what would you like to drink, Mr Morley?’

‘A pint of Adam’s ale for me, please.’

The barman looked at Morley – as barmen often looked at him – with a sort of weariness bordering on contempt.

‘You serve Adam’s ale?’ said Morley.

‘Adam’s ale?’ said the barman.

‘Aqua vitae. The—’

‘Water,’ I said. ‘Please. If you don’t mind.’

‘Water?’ said the barman to me, having given up on a sensible conversation with Morley. ‘He’s wanting to drink water?’

‘That’s it,’ said Morley. And this of course was another of his exotic habits: the ordering of water in pubs and bars. Indeed, among all his habits – the punctiliousness, the hastiness, the continual quoting of Latin tags and English verse, his archaic Edwardian manners, the inopportune quoting of phrases from American movies – it was the drinking of water in public bars that was perhaps the one habit that over the years got us into more trouble than anything else.

‘I’m not sure I’d drink the water,’ said the barman.

‘It’ll be fine,’ said Morley, raising his considerable eyebrows in friendly reassurance. ‘Fine. Nothing finer than a glass of English water.’ He turned around to address the now silent men of the bar. ‘Isn’t that right, gentlemen?’ Reply came there none, and if in Norfolk there were tumble-weed, tumbling it would come. ‘The true and proper drink of Englishmen, barman, if I might paraphrase George Borrow.’

‘George Who?’

‘Borrow?’ said Morley. ‘Late of this parish? Local hero, surely?’

‘Who?’

‘Borrow. George Borrow?’

‘Anybody know George Borrow?’ the barman asked of the silent drinkers.

‘No.’

‘Really?’ said Morley.

‘And you say he’s from Blakeney?’

‘Norfolk, certainly. Dereham, I think. You’re not acquainted? Linguist. Novelist. Friend of the Romanichals?’

‘No,’ said the barman decisively, and he stared at Morley for a moment, attempting to get the measure of him, and then – having got the measure of him – sniffed, wiped his hands slowly on his apron and retreated to the back kitchen, where there could be heard the sound of muttering; and wherefrom an ample-bosomed and rosy-cheeked woman – who might have stepped straight from Maugham’s Cakes and Ale such was her perfectly formed barmaidliness, her body and manner expressing, if one might say so, boundless tolerance, or ‘A woman of robust and welcoming construction’, as Morley later put it – appeared.

‘Everything all right here, gentlemen?’

‘All fine, thank you, madam,’ said Morley, and then turning to me added, sotto voce, ‘Would I were in an alehouse in London, eh?’

‘Indeed, Mr Morley,’ I said, taking the comment merely as a remark.

‘Quotation, Sefton,’ he said.

‘Oh.’ I had come already, within days, rather to dread his love of quotations.

‘Guess?’

‘Shakespeare?’

‘Of course.’

‘Of course.’

‘And which play?’

‘I don’t know. Sorry. I’m tired, Mr Morley.’

‘Tired, Sefton?’ Morley turned his steely blue gaze upon me.

I don’t think in all our years of acquaintance that I ever knew Morley to admit to feeling tired. He would, on occasion, recite out loud, ‘Let us not be weary in well doing; for in due season we shall reap, if we faint not’ – something from the Bible – which seemed to work for him as a kind of charm, or a pick-me-up, like his smelling salts, the proverbial hair of the dog, as it were. ‘What we need is a biblical bracer,’ he would sometimes say, in search of a quote to support some argument or other, as though Scripture were the equivalent of a raw egg with a dash of Worcester sauce. These biblical bracers tended to have the opposite effect on me, making me despair of ever making it through the day.

‘Titus Andronicus?’ I said, when it was obvious – his peering at me enquiringly over his moustache – that he was still waiting for an answer to the question.

‘“Would I were in an alehouse in London?”’ he said.

‘Not Titus Andronicus?’

‘Henry V at battle!’ he cried, as the barman returned and placed a glass of rather cloudy-looking water before us on the bar. ‘Cry havoc, and let slip the dogs of war!’

‘Water,’ said the barman, spilling the contents of the glass slightly.

‘Adam’s ale!’ said Morley, raising the – rather grimy-looking – glass to his lips and then drinking a long draught. The barman watched him keenly, grinning, arms folded, from behind the bar. ‘Ah. Delicious,’ continued Morley. ‘A drop of the old aqua vitae. You know the word derives ultimately from the Irish and Scottish Gaelic uisge beatha?’

‘Does it now?’ said the barman.

‘And what does this phrase mean, you might ask?’

‘I might.’

‘Indeed.’

‘But I won’t, thank you, sir. That’ll be—’

‘Water of life,’ said Morley. ‘Or more commonly—’

I quickly handed some money to the barman and led Morley away to a quiet corner by the fire, where he could do no harm and cause no further irritation.

![]()

Eventually men returned to their drinking and smoking and playing darts, carefully lobbing, I noted, their cigarette ends into the fire with the same accuracy they were scoring on the dartboard, while Morley sat twisting the ends of his moustache, a sign he was deep in thought, as though he were jiggling the wires on a crystal set, trying to tune in to some obscure Hertzian wave or stream of thought. On a table opposite two men sat silently playing a game of shove-halfpenny, clearly listening to every word we spoke.

‘In the church,’ said Morley. ‘Why in the church? Why would he kill himself in the church?’

‘Because that’s where he was?’ I ventured.

‘But he could have been anywhere, could he not?’

‘He could, but he wasn’t.’

‘Exactly. Which brings us back to the question, why in the church? Why not in the rectory? Or out in some woods? Plenty of opportunities for a man to take his own life, aren’t there?’ He took a long sip of water and twisted his moustache some more. ‘Where would you take your own life, Sefton, if you were so inclined?’

The two men opposite listened ever more intently and suspiciously in our direction. This was clearly not everyday pub talk in rural north Norfolk. Though it would hardly have been everyday pub talk in any village, town or city throughout the length and breadth of England: it was simply Morley’s habit to ask the simple, direct sort of question that the rest of us usually see fit to avoid; he was a man who had somehow released the mental valve that most of us manage to keep tight shut. Freud, I often thought, would have had a field day with Morley – and vice versa. I lowered my voice as I replied, my own mental valve being turned firmly clockwise a number of times. I had, in fact, as it happened, considered taking my own life on a number of occasions, and only recently: in Spain, and in London, and by various methods: poisoning; shooting; hanging; jumping from some high place; starvation; lying down in front of a train. The options seemed endless, in fact, though ultimately unattractive. If I could simply disappear, that might have been the answer. Though travelling through England with Morley for all those years, I suppose I did in a sense disappear, or was constantly in the state of disappearing.

‘I’d probably go somewhere quiet,’ I said quietly.

‘Precisely!’ said Morley, too loudly. ‘Any sane man would kill himself somewhere quiet! Not in the vestry.’

‘Probably not, no,’ I agreed, shushing Morley, who could never satisfactorily be shushed.

‘Because there’d be a chance, wouldn’t there, Sefton, of someone walking in, preventing you from going through with it, popping a proverbial spanner in the suicidal works, etcetera?’

‘I suppose so, yes.’

‘So, why run the risk?’

‘Perhaps he was suddenly overcome with despair?’ I suggested, as another cigarette end hit an ember, dead centre. The whole bar seemed to have grown quieter as Morley grew more vivid. I felt the eyes of every man watching us.

‘And in his moment of despair,’ said Morley, ‘he fetched a bell-rope, climbed up on a table, onto a chair, tied the bell-rope into a noose, looped it around the beam, kicked the chair away, and hanged himself? Quite a moment, wouldn’t it be? Not so much a moment, in fact, as a short episode, which implies not only premeditation but also—’

‘I might get myself another drink, actually,’ I said, unable to bear the scrutiny of the other – now once again silent – customers any longer.

‘Good idea,’ said Morley.

‘Good idea,’ I agreed, getting up.

‘I smoked marijuana once, you know, Sefton,’ he continued, ‘through a hookah, in Afghanistan. Herat. Wore a turban. It’s not all it’s cracked up to be. Either the turban or the marijuana.’ He would often throw these googlies into conversation. It was best to ignore them, I found, though the darts-players were clearly having trouble doing so, staring at this white-haired, middle-aged, moustached man as though he had escaped from a lunatic asylum.

‘Another pint of—’

‘The old aqua vitae,’ he said. ‘Yes. Wouldn’t that be lovely?’ And he pulled out a notebook and began writing.

![]()

‘Does anyone commit suicide on impulse, as it were?’ he continued, on my return, tapping his notebook, which was now covered with furious little notes and diagrams. Fortunately, the novelty of having a one-time turban-wearing, marijuana-smoking autodidact among them seemed to have worn off, and men had returned to their conversations, their darts and their shove-halfpenny.

‘I’m sure they do,’ I said.

‘Young people, perhaps. Adolescents. Young Werther and what have you. But a grown man, Sefton? And a vicar, at that. With an eternal perspective? Hardly.’

I took a restoring sip of my beer, and chose not to answer, which was always the best course in such circumstances, I found, since after a few moments Morley was always prepared to pick up a ball and run with it alone.

‘So, what do you think, Sefton, reasons for suicide?’

‘Erm.’

‘If we had to draw up a shortlist. Number one reason?’

‘Erm …’

‘Number one. Mental or physical infirmity. Can’t say at the moment about the physical infirmity – he seemed a fine specimen, but we’ll have to wait for the results of the autopsy to confirm. No one has mentioned the reverend being doolally, have they?’

‘No, not to me,’ I said.

‘Me neither,’ said Morley. ‘One might have expected Mrs Snatchfold to have mentioned it, if he was crazy?’

‘Yes.’

‘So that rather rules that out. Which leaves us with our number two reason for anyone committing suicide. Which would be?’

‘Sorrow?’

‘Precisely! Yes. But sorrow over what exactly?’

‘I don’t know.’

‘Loss? Mourning? Grief, as we know, abides by its own peculiar timetable; but it seems unlikely, I think. What do you think?’

‘Erm …’

‘He may of course have been in some sort of practical discomfort. Financial distress, possibly. Debt? A gambler? In which case someone locally would be able to tell us. Which leaves us a long list of other reasons for sorrow, including perhaps remorse, shame, fear of punishment – God’s or otherwise – despair due to unrequited love, thwarted ambition—’

‘Quite a lot of possibilities.’

‘Exactly, Sefton. Which means it’s probably the wrong question to ask. Too many answers: wrong question. So, let’s work on the basis of what we do know rather than what we don’t, shall we? Let’s imagine, just for a moment, Sefton. Let’s put ourselves in the role of the poor departed reverend. This man who decides to kill himself in his own church.’

One of the darts-players scored a triple top, to much celebration.

‘Bravo!’ said Morley, joining in, and then continuing without a break. ‘Let’s just think about it for a moment, Sefton. The life of a country priest.’ He pointed to a diagram in his notebook: a series of circles and letters, and noughts and crosses, like a set of primitive pictograms or strange celestial symbols. ‘Here he is. The reverend.’ He pointed to a small black cross inside a large black circle. ‘Now, what does a reverend do, on a daily basis?’

‘Preaches?’

‘Yes, of course, he preaches. Though weekly, we might assume, rather than daily. But, you’re right of course, he does preach. Hence …’ He pointed to a line that led from the large black circle to a smaller circle containing a capital P. ‘Anything else?’

‘He visits the sick?’

‘Again, yes,’ and he traced his pen along another line out towards another circle containing the letter S. ‘He does indeed. Chum to the weak, and what have you. But what is most important about the role of the priest, town or country, in the Holy Roman and Apostolic Church?’

‘I don’t know, Mr Morley.’ My mind sometimes wandered when Morley was pursuing a theory, adumbrating a theme, or sketching.

‘The sacerdotal role, is it not?’ He drew a circle around all the other circles, creating a kind of wheel with spokes. ‘The priest is set apart from the community, Sefton. Everything that represents worldliness – the love of pleasure, of art, of ourselves. The priest is supposed to be essentially different from us.’ He drew half a dozen small arrows attempting to penetrate the large circle.

‘I see.’ I had absolutely no idea what was the point of the diagram now.

‘He’s a symbol, isn’t he?’

‘I suppose.’

He took a long draught of his water.

‘So, the point?’

‘It’s just an illustration, Sefton, to help us think.’

‘Right.’

He tore the page from his notebook and fashioned it into a small dart.

‘Now, Sefton. Watch.’ He squinted. ‘On the oche!’ he said and leaned back, and then promptly threw his little dart straight into the heart of the fire, where it burst into flame. ‘One hundred and eighty!’ he cried. The darts-players responded with a polite round of applause. Morley bowed in his seat and took a couple of celebratory twists of his moustache. ‘You’re a city person, Sefton, aren’t you?’

‘Yes. Born and bred in London.’

‘Can you imagine for a moment, then, living somewhere like this?’ He swept his arm wide, almost knocking our drinks to the floor.

‘Well …’

‘And every day you’d have to meet the same people. The same people in your place of work. The same people in the pub. Our darts-playing friends here …’ Our darts-playing friends glanced over. ‘Day in, Sefton, day out. Week in, week out. Year in, year out. People you might not like. And who might not like you. And yet you can’t leave, Sefton. You can’t go anywhere. Because your role as parish priest is to serve them. All of them.’ He threw his arms wide again, once more narrowly missing our drinks. ‘And in return, Sefton, they are expected to respect you, to look up to you, to see you as a representative if not of Christ exactly, then at least of the Church, and for you to express and uphold its values, and yet and yet and yet’ – a final arm fling, which fortunately I saw coming, and had snatched away our glasses – ‘they see you every day, conducting your duties in the same way we all conduct our duties, which is to say inconsistently and incompletely. They see your failings and your petty grievances and faults. Might not the temptation eventually be …’

I placed the drinks safely back down on the table. ‘To kill yourself?’ I said.

‘Wrong!’ cried Morley, this time finally throwing his arm wide enough and quickly enough to knock both our glasses successfully to the floor. The unmistakable sound, first, of breaking beer glasses; second, of the absolute silence following the breaking of beer glasses; and third, and finally, of the fulsome barmaid, on uncertain heels, hurrying to resolve the breaking of beer glasses. And then … the equally unmistakable sound of Morley, continuing on.

‘Terra es, terram ibis,’ he said.

‘Sorry, sir?’ said the barmaid.

‘Dust thou art, to dust thou shalt return.’

‘If you say so, sir.’

‘I really am terribly sorry. I have an awful habit of talking with my hands, I’m afraid. A touch too much of the old Schwärmerei, eh?’

‘I’m sure it is, sir. But not to worry,’ said the barmaid of boundless tolerance, who was bending over to pick up the larger shards of glass from the floor, and mopping at the beer and water with a dishcloth. ‘We’ll have this cleared up in a moment, sir.’

I got down on my hands and knees to help, not least because the barmaid’s heels and clothes rather inhibited her free movement. She was dressed primarily for display purposes.

‘Don’t you be troubling yourself with that, sir.’

‘Nonsense,’ I said. ‘It’s the least I could do.’

‘Mind your fingers.’

‘I will,’ I said. And for a moment – something to do with the light, the woman, the smell of beer – I was back in a bar in Barcelona where there was a banner up outside: ‘Las Brigades Internacionales, We Welcome You’.

Between us we made a pretty good job of clearing up, and the bar chatter gradually resumed.

‘I’ll help you get rid of this,’ I said, my hands cupping broken glass.

‘There’s no need,’ said the barmaid.

‘It’s fine,’ I said. ‘I need to get us both another drink anyway.’

‘Ubi mel ibi apes, eh, Sefton?’ said Morley.

‘Is he foreign, your friend?’ whispered the barmaid as we walked to the bar with all the sharp little pieces.

‘He’s just … eccentric,’ I said.

‘All right, Lizzie?’ asked the barman, as we dropped the broken glass into a bucket behind the bar.

‘We’re fine, John.’

‘Can’t you keep your friend under control?’ said the barman.

‘Yes,’ I said. ‘I mean, no. Not really, no, I’m afraid he’s …’

‘He’s harmless,’ said the barmaid. ‘Leave him alone, John.’ She straightened up and faced me, cocking her head to one side. ‘You’re staying in the hotel?’

‘Yes, we are. Just for a night or two.’

‘Well, we’ll see lots of you in here then, I hope. You make a nice change.’

‘Indeed,’ I said.

![]()

‘The temptation, Sefton,’ continued Morley, once I had brought us fresh drinks and settled down again, ‘would not be to kill oneself, surely, but to kill them, would it not?’

‘What?’ By this stage all I wanted was to drink my beer quietly and get to bed.

‘Does it seem so strange?’

‘I’m sorry, Mr Morley, I can’t quite seem to understand what it is you’re suggesting.’

‘I’m not suggesting anything, Sefton. I’m simply remarking on the obvious fact that anyone and everyone might at some time be tempted to kill themselves. Or indeed others. Your experience in Spain would bear that out, would it not?’

‘I don’t know.’

‘Do you know Durkheim?’

‘No, I’m afraid not. Not personally no.’ I had no idea who he was talking about.

‘German. Cranky. Beard, etcetera. But useful distinctions between types of suicides. We are assuming that the reverend’s is an act of egoistic suicide, self-directed, an act of self-harm. But what if it’s not? What if it’s a suicide aimed specifically at others? An aggressive suicide, if you like? What if the question is not, why would the reverend want to kill himself, but rather why would the reverend want to kill others?’

‘No. I’m sorry, I don’t follow.’

‘Put yourself in the sacerdotal shoes for a moment, Sefton. Try imagining yourself as a vicar in a small Norfolk village, squeezed into the reverend’s shoes – four-eyelet tan brogues, were they not? With rubber cleated soles? Cordovan leather, possibly.’

‘I didn’t notice,’ I said.

‘Doesn’t matter,’ said Morley. ‘Not literally, metaphorically I mean, of course. So how do they fit? Eh? The good reverend’s shoes?’

‘A bit uncomfortable,’ I admitted.

‘Indeed. Tight fit, isn’t it? Tell me, do you really hate anyone, Sefton?’

‘Well …’ At that moment, one obvious example came to mind.

‘Absolutely hate their guts, I mean? Loathe them, despise them? Regard them as lower than vermin? As worms? Ants? Fit only to be crushed under your heel?’

‘Maybe not.’

‘Don’t be afraid to admit it, Sefton. These are human emotions, after all. Perfectly normal.’

‘Well, I suppose … yes.’

‘Good! And we know you to be a fine young man. So is it not possible therefore that the reverend felt likewise, or that others felt likewise towards him?’

I had to grant this was indeed possible.

‘Which is how we might end up with … this.’ He jerked a hand up behind his neck, as though hanging himself by a rope. The darts-players looked suspiciously in our direction. I looked nervously towards them.

‘I think perhaps you should keep your voice down, Mr Morley, actually, to be honest.’

‘Really?’

‘Yes. I’m not at all sure about your theory, and I think—’

‘Well, why don’t we ask one of these chaps what they think?’ He nodded in a friendly fashion towards the men playing darts.

‘I’m not sure they want to be disturbed, actually.’

‘Everyone wants to be disturbed, Sefton.’

‘I’m not sure about that, Mr Morley.’

‘And yet simultaneously everyone wants to be left alone. There’s the rub, you see. What about that chap there?’ Morley pointed towards a man just about to throw a dart. ‘He’s the man to ask.’

‘Is he?’

‘I think you’ll find he’s the bell-ringer in the church.’

‘How do you know?’

‘Broad shoulders. Heft. Broken nose – could be a boxer. But one arm, as you’ll note, overdeveloped. Hence not a boxer. Most likely from pulling on ropes.’

‘Or playing darts.’

‘Yes, I suppose, it could be either.’

‘Well, I’ll wager you, Mr Morley, that I’m as likely to be correct in this as you.’

‘I’ll not accept the wager, Sefton, thank you. We should abstain from the appearance of evil. But I wonder, would you mind awfully buying him a drink and asking him over?’

‘Now?’

‘When you’re ready.’

I got up to go over.

‘And Sefton?’ Morley added.

‘Yes, Mr Morley?’

‘I think you’ll find that I am correct.’

![]()

He was correct.

The bell-ringer’s name was Hackford. He had bright blue eyes, bristly red hair, a drinker’s nose, hands like smoked hams and a stinking black pipe. He also wore, perched atop his head, a regimental beret.

‘Royal Warwickshire Fusiliers?’ asked Morley.

‘That’s right,’ said Hackford.

‘My son was in the 16th Battalion, London Regiment,’ said Morley.

‘Was he, now?’

‘Yes.’ Morley gave a slight cough and changed the subject. ‘Did you know the reverend well?’

Mr Hackford tugged on his pipe and took a long time to answer, in the traditional Norfolk fashion.

‘As well as any man knows his vicar.’

‘And what did you think of him?’

‘It’s not for me to say, sir, is it?’

‘No, of course,’ said Morley. ‘A terrible tragedy, though.’

‘He was a good vicar,’ agreed Hackford, raising his tankard from the table.

‘Really? And what makes a good vicar, do you think?’ said Morley.

Hackford took a long draw on his pipe, blew out great rings of smoke, as though he were ringing a peal of bells, and swallowed a vast mouthful of beer.

‘He was a good preacher. And he’d listen if you had a problem.’

‘I see. And you went to him with problems yourself?’

‘I did not, no.’

‘But others did?’

‘Maybe so.’

‘So he was popular with the congregation, I’m sure.’

‘I suppose.’

‘Not popular, then?’

‘You always gets your grumblers,’ said Hackford.

‘So not universally popular?’ said Morley.

Hackford fixed his eyes steadily on Morley. ‘Might I ask you a question, sir?’

‘Of course,’ said Morley.

‘Are you universally popular?’

‘Perhaps not, Mr Hackford.’ Morley laughed. ‘Perhaps not. Can I ask, though, did you speak to the reverend during the service on Sunday?’

‘I rang the bells, same as usual. Then I made my way home.’

‘What did you ring, if you don’t mind my asking?’

‘On the bells?’

‘Of course.’

‘You’re a bell-ringer, sir?’

‘No, not myself, alas, but there’s a very good book, by Dorothy L. Sayers. Nine Tailors. Novel. Do you know it?’

‘I can’t say as I do, sir, no.’

‘Very good. Lot of campanological stuff in it.’

‘I’m afraid I don’t know what you’re talking about now, sir.’

‘Campanology is the study of the subject of bell-ringing, Mr Hackford. Surely you—’

‘I don’t study ’em, sir, I just ring ’em.’

‘Of course. And was there anyone in the vestry, that you were aware of? Anyone who shouldn’t have been there?’

‘I don’t think so. But I was in the other tower, ringing.’

‘And did you notice anyone in the congregation you hadn’t seen before?’

‘No.’

‘You’re absolutely sure?’

‘I know everyone in the congregation of St Nicholas by now, I think, sir. I’ve been worshipping there for sixty-one years.’

‘The family of the church,’ said Morley.

‘That’s what they say, sir, yes.’

‘Jolly good!’ said Morley. ‘Quite right.’

Hackford set his empty tankard down on the table, and looked at me. ‘Is that it?’

‘Yes, that’s it,’ said Morley.

‘Another drink, Mr Hackford?’ I said.

‘I’ll not, thank you,’ said Hackford. ‘I have to say, you’re a great man for the fine words and phrases, Mr Morley.’

‘I shall take that as a compliment, Mr Hackford, thank you.’

‘As a compliment it’s meant.’

‘Well, thank you.’

‘But you’ve no business being here,’ said Hackford, getting up and walking off.

‘Seem to have upset him,’ said Morley. ‘Strange.’

![]()

I tried to persuade Morley to leave the bar then with me, but he insisted that he wanted to stay. It was his reading hour: he set aside a portion of every evening to read a book on a subject he knew nothing about, and tonight, he said, would be no different. And so I left him, among the hostile bar staff and darts-players of Blakeney, perfectly content, and about to start – and doubtless finish – a book on eighteenth-century French furniture. I, on the other hand, excused myself and said I would retire early.

‘Resembles the Hayter portrait of Queen Caroline, doesn’t she?’ said Morley, as I got up to leave.

‘Sorry? Who does?’

‘The barmaid. Very striking-looking. Regal of bosom, wouldn’t you say?’

‘I can’t say I’ve—’

‘And her dress – rather daring, isn’t it?’

‘Is it? I don’t know. I didn’t notice.’

Morley raised an eyebrow. ‘The effect is inquiétant, I think is the French, is that right?’

‘I don’t know.’

‘Hmm. Word to the wise, Sefton. Omne ignotum pro magnifico est.’

‘Everything … unknown … is—’

‘Distance lends enchantment, Sefton, is all I shall say. Tacitus. Agricola. Look but don’t touch, eh? Highest standards to be maintained at all times on your journeyings, if you don’t mind.’

‘Of course.’

‘I’m sure she appreciated your assistance, Sefton. Very selfless of you.’

‘Yes.’

‘Sleep well.’

‘Yes, you too, Mr Morley. Goodnight.’

He produced his egg-timer from his jacket pocket, and propped his book before him.

‘There we are. All set.’ He caught me looking at him. ‘The elusive waywardness of time, Sefton,’ he said mildly, as if in explanation. ‘We must do everything we can to capture it, must we not? Not a moment to waste.’

![]()

As it happened, I slept for no more than an hour or two that night, before finding myself jerked awake, as was often my habit, in a cold sweat, the same persistent nightmares troubling me. I opened the curtains in my room, and saw that a blood-red moon had set outside. It was ten past midnight. I felt unaccountably excited and fearful, as though something was about to happen that I could not prevent, nor wish to avoid. I sat smoking for some time – until almost one o’clock – and then, still unable to sleep, I dressed, and found myself wandering through Blakeney village. I was inexorably drawn to the church.

Constable Ridley was stationed outside, with a candle lantern.

‘Evening, Constable,’ I said as I approached.

He jumped out of his skin, pulling a truncheon from his pocket, and bringing his shiny whistle to his lips.

‘It’s only me!’ I said.

‘Ah. Thank goodness,’ said Ridley. ‘Good evening, sir. Sorry, I was maybe dozing there for a moment. You won’t mention it to anyone.’

‘No, of course not.’

‘Good. Meant to keep awake, to watch the church, in case anyone tries to tamper with the evidence.’

‘Quite right. Your chaps from Norwich are here, then?’

‘Yes, sir. Just arrived a couple of hours ago. They’ll be wanting to talk to you tomorrow, no doubt.’

‘Good.’

‘And then you can be on your way.’

‘Let’s hope so.’

‘Yes.’

‘Well. Lovely evening, isn’t it?’

‘It is indeed. A little late for a stroll though, sir?’

‘I couldn’t sleep.’

‘Ah. You’re not the only one.’

‘Really? Why? Who else is out?’

‘Her.’ He nodded his head.

‘Who?’

‘The reverend’s maid.’

I looked across the graveyard and saw Hannah. The brightest stars shone through the evening mist. Her cigarette glowed in the distance.

‘She’s been here the whole time?’

‘I’m afraid so. I can’t persuade her to leave.’

‘Is everything all right?’

‘I don’t know. She won’t say a word to me.’

‘Should I …?’

‘Be my guest. Can’t do any harm.’

I approached her across the graveyard. There was the hooting of an owl.

‘Hannah? It’s me, Stephen Sefton. Is everything all right?’

She looked at me with those dark, intelligent, sorrowful eyes, and reached out a hand towards me.

I took her hand and she drew me immediately into an embrace. I could feel her breath in the silence. She held on to me for a long time and then, suddenly, I felt her weight shift, as if her body had made some decision, and she tilted her head up and forward, and kissed me on the mouth.

I was shocked, of course, but I kissed her back, and again we stayed that way for a time, calmly, without urgency, as though lovers long familiar, and then something changed again and I felt her breasts press urgently against my chest, and her arms grow tighter around my shoulders, and suddenly we were moving together deeper into the shadow of the church, now out of sight of Ridley.

And then … her back was pressed against the wall, and we were kissing, and then we were moving frantically together, her moaning a little as we did so, pressing against me, turning her head as she placed my hand gently over her mouth as she rocked her body against mine.

It was not the right place, or the right time. It was real, and yet had the substance of dreams.

It was just something that happened.

I returned to the hotel around two in the morning, took two sleeping tablets, and fell into a troubled sleep, confusing the softness of Hannah’s body and her dark flashing eyes with memories of couplings in Spain, when we were all maddened by war, and under threat, and desperate, our lives glowing white-hot in the heat of the burning sun, the sands of time running out before us.