‘WHAT EXACTLY is a sherry party?’ asked Morley. ‘I’ve often wondered.’

‘It’s like a cocktail party, Mr Morley. Only on good behaviour.’

‘Ah. Yes. So I feared.’

We had received our invitation on our return to the Blakeney Hotel. I had to persuade Morley to agree to attend, he was beginning to fret so terribly over the continuing delay to our timetable. We should, according to Morley’s plan, have visited most of the churches of Norfolk by now, and investigated its major industries, visited all other places of cultural and historical interest, written up our notes, and been preparing to leave for our next county. Instead, we were stranded in a quayside village in the middle of nowhere, and Morley was becoming restless – a terrible danger, like the dog without its bone, or a man without meaningful work. Morley had to be – as he himself might relate it – in mobile perpetuum. If he wasn’t, he grew first irritable, and then angry, and then, curiously, utterly listless, like a man falling into a trance or a coma. He was, at this stage in his perpetual cycle, becoming so restless that it was all I could do to talk him down from a plan to start producing our own evening expedition newspaper, based on the model of Scott’s South Polar Times (‘All we need is a printing press,’ he claimed. ‘Miriam could bring us something up from London, I’m sure’). To distract him, I had taken to playing speed chess with him, but things had got so bad, and he won so consistently, without joy or pleasure, that he was now threatening to get out his knitting – another one of those hobbies that, during our years together, was the cause both of much amusement and much trouble. (He was apt to launch into demonstrations and explanations of the craft – which had been taught to him by the menfolk of Taquile Island on Lake Titicaca, he said – at the most inappropriate of moments. The story of Morley, the dead baby and the mystery of the knitted shawl is perhaps not as widely known to the general public as some other episodes; I shall relate it at another time.) Frankly, the sherry party seemed like a welcome alternative to an evening discussing the history of Peruvian woolly hats.

‘But I cannot abide parties, Sefton,’ he protested.

‘But this is only a sherry party, Mr Morley.’

‘Sherry party. Cocktail party. Card party. Shooting party. House party. Musical party. Salon. Cénacle. Soirée … Same region, soil and clime, Sefton. Waste and wild, the lot of them. Waste and wild.’ He sighed a grand, Miltonic sigh. ‘And as for the timetable … It’s slipping, Sefton. We’re drifting dangerously off course. We must keep to the timetable.’ Panicked and agitated, he could sound worryingly like Ismay on the Titanic. ‘I don’t know if I can get us back, Sefton. It may not be possible.’

Given how far we were now off course, I managed to persuade him that a sherry party would hardly prove disastrous and that, besides, it might give us an opportunity to find out more about the unfortunate death of the reverend, which of course remained the cause of our spirit-sapping detention.

![]()

And so we found ourselves, on a balmy summer’s evening, at the Thistle-Smiths’, a rather bleak eighteenth-century house on the edge of Blakeney village, set about with mournful, desolate-looking laburnum hedging but stuffed inside both with lively guests and with Mrs Thistle-Smith’s extraordinary bonsai collection, displayed in Ming bowls set on tables, shelves and plinths in the entrance hall to the house, and which gave the impression of one entering an enchanted forest inhabited by gibbering giants.

‘Imitation Ming bowls, actually,’ Morley later corrected me. ‘For what I think might be more accurately described not as an “extraordinary” collection – for what, one wonders, might a merely “ordinary” collection of bonsai be, eh? – but rather as a plethoric collection of bonsai. Hmm? Plethoric, somnolent bonsai, one might say, if one needed the extra adjective, Sefton.’

In attendance, in addition to the plethoric somnolent bonsai, were the Grices, the Chapmans, the Wells, and many other north Norfolk worthies and dignitaries whose names escaped me.

‘Everyone is here!’ proclaimed Mrs Thistle-Smith on our arrival, meaning, presumably, everyone in the village with an income, earned or unearned, above about ten pounds per week: a sherry party in north Norfolk being most definitely not a place for the common man. One might as well have been in Mayfair, the only difference being that the rich in the remoter corners of England seem uniquely and peculiarly unburdened when compared to their city counterparts, as though permanently on holiday, the men utterly self-satisfied and comfortable in their moth-eaten, third-generation tweeds, and the women thoroughly relaxed about both their mothballed appearance and their antique charms, though with the exception, I should say, of Mrs Thistle-Smith herself, who was a rather determinedly glamorous, made-up sort of lady, who would not have been out of place as a hostess at one of Miriam’s parties down in London, and who was doggedly hanging on both to blonde hair and to fashionable clothes, and who clearly had no intention of allowing her young mob-capped and aproned maids to steal any of her sherry party limelight. Mrs Thistle-Smith was one of those older women who possess – and who are clearly not unaware of possessing – what one might call full candlepower presence, her welcoming smile, her voice, her manner and her powerful wreath of perfume acting like the rays of the sun shining down upon one. One had the feeling with Mrs Thistle-Smith that she had just conjured you into life on her doorstep, and that any previous existence had been merely a kind of limbo, waiting to be summoned forth into her life-giving light. I’m afraid I found her scintillations rather off-putting, but was nonetheless delighted to be able to accept the proffered glass of oloroso, and the promise of an evening’s conversation unrelated to cross-stitch, needles and thread.

‘Remember, sherry is not a cordial, Sefton,’ said Morley, peering at me disapprovingly over his moustache.

‘Now, Mr Morley, what can I get you, a dry fino or a sweet amontillado?’ said Mrs Thistle-Smith in her finest silk-and-cashmere tones. She quickly and gently brushed a hand against Morley’s arm as she spoke, establishing contact. I thought I saw Morley jerk away slightly as she did so. It was not an auspicious start.

‘I’ll have a glass of water, madam, if I may?’

‘Water? Really? Are you not well?’

‘No, not well, madam. That’s right.’ Morley seemed uncharacteristically guarded.

‘If you’re sure? You wouldn’t rather something else? A cocktail, perhaps?’

‘No, thank you. Not a cocktail.’

‘I know that Mr Thistle-Smith has a nice Cockburn ’96 reserved for himself, but I could get one of the girls to fetch it.’

‘No. That won’t be necessary, madam. Water would be my preferred choice.’ His tone was disapproving.

‘Ariston men hudor,’ said Mrs Thistle-Smith.

‘Indeed,’ agreed Morley. I detected an instant thawing of tone. He loved a Latin – or indeed a Greek – tag. And, as it turned out, he loved a woman who loved a Latin – or indeed a Greek – tag.

‘Well, I for one am in complete agreement with you, Mr Morley. There is surely nothing better for man than the taste of water.’

‘Exactly,’ said Morley, who seemed suddenly to be flushing under Mrs Thistle-Smith’s warming attentions. ‘I couldn’t agree more.’

‘I have a great love of water,’ said Mrs Thistle-Smith, sherry glass in hand. ‘Fountains, springs, mountain pools. So refreshing. So joyous.’

A maid was duly dispatched for water, and we were shown through the house into the garden room, passing on the way a vast excess of paintings, furniture and ornaments which had somehow been hoisted, yanked and crammed into every nook and cranny. One room we passed was filled almost entirely with chairs, huddled together like sheep in a pen – Chippendales and Hepplewhites, Charles the Second chairs with straight backs, little duets and trios and quartets of Victorian slipper chairs, every conceivable type of chair. It really was the most peculiar sight: the house as a storeroom rather than a home. I had recently read F. Scott Fitzgerald’s short novel The Great Gatsby: the house struck me as the Norfolk equivalent of a West Egg mansion. I mentioned this later to Morley. ‘Wrong,’ he said. ‘East Egg, you mean. Not West Egg. Do pay attention in your reading, Sefton.’

‘Are you or Mr Thistle-Smith a collector, perhaps, madam?’ asked Morley.

‘I am, Mr Morley, for my sins. I don’t know what Herr Freud would say about it.’

This seemed further to arouse Morley’s interest, his interest already having been well and truly piqued, truth be told, by Mrs Thistle-Smith’s welcoming balm. She might as well have revealed that her real name was Flaubert or Turgenev.

‘If you don’t mind my saying so,’ he said, ‘the name of Sigmund Freud is not one that one would expect to hear from the lips of the average Norfolk hostess.’

Mrs Thistle-Smith raised a well-tended eyebrow in response and pursed her carefully lipsticked lips.

‘Then – if you don’t mind me saying so – you can perhaps assume, Mr Morley, that these are not the lips of an average Norfolk hostess.’

‘Indeed.’

And so ineffable charm met endless curiosity, and seemed to find each other quite fascinating. The two of them proceeded to spend some time discussing the finer points of collecting and psychoanalysis.

I made my excuses, took another glass of sherry, and mingled.

Small tables had been arrayed around the garden room, without chairs, intended presumably to suggest that one might move casually and informally among one’s fellow guests, but suggesting also, alas, the odd, uncertain appearance of a railway station waiting room. The combination of faded velvet brocade, the cool tiles, the golden, misty light of the early evening, and the vague promise of less than fresh viands, reminded me also of a brothel I had visited in Barcelona.

There was the chattering murmur of voices, there were men and women of Dickensian features, there were fanciful flowers displayed in fine porcelain vases, and there were canapés. After one or two more glasses of sherry and a polite conversation with a woman who insisted on telling me about her love for the work of E. Nesbit, I realised that I was hungry, having subsisted largely, despite Morley’s deprecations on breakfast, on cigarettes and coffee. Maids were circulating with small plates of food, and I excused myself from my interlocutor and homed in on the nearest tray. Quail’s eggs. I was disappointed, the peeling of quail’s eggs being a task, I find, requiring efforts much greater than the rewards, which are both insubstantial and less nourishing even than a railway sandwich.

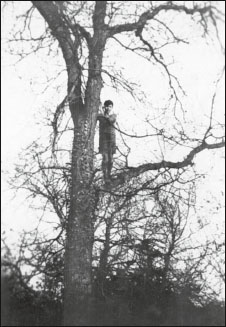

Thomas Thistle-Smith

‘I’ll do it for you, mister.’ A boy in a blue velvet suit had appeared at my elbow. He held out his hand. He was probably no more than twelve or thirteen years old; there was, on his lip, the faintest hint of an incipient moustache, and his voice wobbled on the very furthest, most querulous edge of the soprano. He had thick, dark hair that hung down to his shoulders.

‘You’ll peel the egg?’

‘Yes, sir, I will, sir. I’m an expert, sir.’ His face and his manner were, all at once, open, bold, mild and teasing – as though I were merely an entertaining discovery, and he knew well in advance the outcome of our exchange.

‘You’re a quail-egg-peeling expert?’ I asked.

‘Yes, sir. That’s right, sir.’

‘Employed especially for the evening?’

‘By my mother, sir. Yes, sir.’

I glanced around but could see no obvious hovering maternal presence. ‘Is your mother the cook?’

‘No, sir. My mother is the lady of the house, sir.’

‘Mrs Thistle-Smith?’ I was surprised. Mrs Thistle-Smith seemed a lady long since past her child-rearing years.

‘Indeed, sir. I am Thomas Thistle-Smith, sir.’ He shook my hand, one eye still firmly on the quail’s egg. ‘My friends call me Teetees, sir.’

‘Teetees?’

‘Yes, sir. And my mother always allows me to assist at her parties, sir, if I’m home from school. I’m not allowed to eat them. Only to peel them. I’m a champion quail-egg peeler, sir.’

‘Are you, indeed?’

‘Yes, sir. If you’d like, sir, I’ll challenge you.’

‘Challenge me?’

‘If you can peel a quail’s egg quicker than me I’ll give you a shilling, sir.’

‘A shilling? And I suppose if you can peel an egg quicker I give you a—’

‘Shilling. That’s correct, sir.’

‘Very well, then.’

I held my quail’s egg at the ready. The boy took a quail’s egg from a dish.

‘Ready,’ he said. I braced myself. ‘Steady. Go!’

I started fumbling with the blasted thing, but only a second later the boy held his peeled egg aloft, triumphant.

‘That’s incredible,’ I said, for incredible indeed it was.

‘Practice makes perfect, sir.’

He held it – tiny, bald, rather grey-looking – out towards me. It looked sad and old rather than shiny and new. I detected hints of pocket lint. I suspected foul play and sleight-of-hand.

‘That’ll be a shilling then please, sir.’

‘A shilling!’

‘Yes, sir. It goes towards my school fees, sir.’

‘Your school fees? You need to peel a lot of quail’s eggs to cover your school fees.’

‘Just for the incidentals, sir. There are always incidentals.’

‘I’m sure there are.’

I handed over sixpence. He handed over the peeled egg. He looked at the coin. I ate the egg.

‘Hold on,’ said Teetees, too late. ‘This is only a sixpence.’

‘Correct,’ I said. ‘And this is not a freshly peeled egg, is it?’

‘Of course it is!’

‘Really?’

The boy had exhausted my patience. I was hungry. I had drunk several glasses of sherry, and I had the prospect of a long evening ahead with Morley. I reached forward and forcefully patted the pocket of his blue velvet jacket – and sure enough there came the answering sensation of a handful of tiny pre-peeled eggs squashing together.

‘Hey!’ he said. ‘Hey! They’re my eggs!’

‘Goodbye,’ I said.

He scowled at me, and I scowled back, and he disappeared into the crowd, ready to pester others with his pre-pubescent upper-class begging.

Morley, meanwhile, had been temporarily abandoned by Mrs Thistle-Smith, who was now busy elsewhere in scintillating sherry-party conversation, and he had sought out, or been found by Dr Sharp, who had attended the body of the reverend on our first night in Blakeney. Their voices could be heard faintly over the hubbub, and I felt the distant twitching of Morley’s moustache, always a sign of great danger. I hurried over.

‘The answer, Morley, if you would care to listen, is birth control,’ the doctor was saying. It looked as though I was too late. ‘As you know, nature exercises a certain amount of control by effectively sterilising the alcoholic and the diseased, and I am simply saying that there is no good reason why we shouldn’t augment her role and prevent some other types of unsuitable breeding. It’s hardly unreasonable, man.’

‘It’s eugenics,’ said Morley.

‘It’s birth control,’ said the doctor flatly.

‘And who is it who controls the births? Doctors like yourself, presumably?’

‘I can think of no others better suited, Mr Morley. Can you? And certainly if individuals are incapable or unwilling to make the right decision—’

‘Sorry, doctor. Forgive me. Incapable or unwilling in precisely what sense?’

‘Precisely through background, or education or—’

‘Race?’ said Morley.

‘Potentially, yes,’ said the doctor.

‘Mr Morley?’ I said, alerting him to my presence.

‘Ah, there. You see, Sefton?’ He had – as was his habit – instantly recruited me onto his side of the argument. ‘A rather troubling suggestion, wouldn’t you agree, doctor?’

‘I don’t see why,’ said the doctor.

‘Well, try telling the Aga Khan he can’t have any more children, doctor. Eh? Or the Emperor of Nepal. Or the tribal chiefs of Rhodesia and Nyasaland. Or the rabbi of—’

‘That is clearly not what I meant, Mr Morley, and I have to say that I am rather disappointed by your failure to take my argument seriously.’

‘I’m taking your argument very seriously, doctor.’

‘Mr Morley?’ I said again, to no avail.

‘Good,’ said the doctor. ‘So you’ll understand that I am talking about individuals who cannot provide or account for the consequences of their actions.’

‘And you can provide and account for the consequences of all your actions, doctor?’

‘I certainly expect no one else to bear the consequences. And I hardly see why we as a nation should bear the responsibility for those born without the capacity to progress or succeed in life.’

I glanced at Morley’s face. He looked utterly disgusted, as though having eaten half a dozen rotten quail’s eggs.

‘I would have thought, doctor,’ he said, ‘that was an argument beneath the dignity of a man like yourself. But clearly I was wrong.’

The doctor’s face reddened. ‘I don’t see what’s wrong with it,’ he said.

‘Which is precisely what’s troubling,’ said Morley. ‘It is the beginning of the slippery slope, sir.’

‘Towards?’

‘A deep world of darkness, doctor. A place I would rather we did not go, but where I fear we are plunging headlong.’ Morley took a sip of his water to fortify himself. ‘What of the mentally unstable in your scheme, doctor? Or, shall we say, the merely psychologically quirky? The mentally or physically kinked and twisted. Have them all neutered, should we?’

‘Not necessarily,’ said the doctor.

‘Not necessarily, Sefton, eh? Did you hear that? Very generous of him, isn’t it?’ He was becoming uncontrollably roused. I had seen the signs before.

‘Mr Morley,’ I said again. ‘Sir, I think we—’

‘The epileptic, I take it, you think should automatically be kept from breeding?’

‘No. Not necessarily,’ said the doctor. ‘Certainly not. But possibly, under certain circumstances, yes.’

‘And so what of Milton?’ said Morley. ‘And of Keats?’

‘There would be exceptions, Mr Morley.’

‘And you would be able to identify these exceptions, in vitro? The good epileptic from the bad? The foetus capable of progressing and succeeding in life from the inevitable failure? The wheat and the chaff separated in the belly of a woman? The sheep from the goats, in the womb? It’s outrageous, frankly, doctor. Absolutely and utterly—’

‘Mr Morley,’ I said. ‘I think—’

‘Again, I’m afraid you’ve misunderstood my argument, Mr Morley, and twisted it, and taken it too far.’

‘The only place to take an argument, surely,’ said Morley. I had a hold of his elbow by this stage, and was attempting gently to tug him away. But he was standing firm. ‘To test its eventual outcome? It’s called the Socratic method, sir, and I would have thought a man of your background might have encountered it during the course of your long and privileged education.’

‘Mr Morley! Sir!’ I interjected as loudly as I could without disturbing the other guests, though noting that already those around us had begun to take notice of the kerfuffle.

‘And what about homosexuals?’ continued Morley, horribly. ‘Dock their tails too, should we? Hmm?’

The doctor blushed red to the roots of his Brylcreemed hair.

‘Hmm?’ continued Morley, rather cruelly, I thought, but clearly to the point. ‘Medice, cura te ipsum!’

The doctor had turned away, and I steered Morley fast into what I thought might be calmer waters over by the windows to the garden. Alas, I miscalculated. A schoolmaster, a perfectly agreeable man named Ellison, with a wide, pleasant smile, and the innocent face of a child, introduced himself to us. He was the wrong person in the wrong place at the wrong time.

‘A friend of mine attended one of your lectures in London,’ he said warmly, after the introductions. ‘They said it was most entertaining.’

‘That’s nice, isn’t it?’ I said, hoping to calm Morley.

‘Schoolmaster are you, eh?’

‘That’s right,’ said the poor unwitting, grinning Ellison.

‘And would you agree with me then, sir, that the entire problem with our system of education is the problem of our public schools?’

‘I’m sorry?’

‘No need to be sorry, young man. Where do you teach?’

The teacher mentioned a prep school nearby of high reputation, and even higher prices.

‘I see. As you may or may not know, sir, I have spent most of my working life doing my best to offer some skimpy education to those less fortunate than your pupils, those who some among us indeed’ – he pointed at the distant figure of the doctor, who was refreshing himself with sherry and cake – ‘believe are incapable of progressing or succeeding in life.’

‘Yes, Mr Morley, I know your—’

‘And it is my belief, in fact, that our public schools are responsible not only – not only – for the dulling and stultifying of the young minds with which they are entrusted, doing nothing more than repressing the intellect and the imagination with their pathetic idolatory of athletics and rugby, but are responsible also for the perpetuation of inequalities of opportunity in this country of which we should all be rightly ashamed. Am I right, do you think, in my assessment of the state of our education system?’

‘Well, sir … I don’t know.’

The schoolmaster looked at me, bewildered, evidently unsure whether he should mount a sturdy defence of his profession. The situation clearly called for decisive action. By chance I was able to grab hold of Mrs Thistle-Smith as she circulated past.

‘Mr Morley,’ I said, ‘was wondering if he might take a look at your garden, Mrs Thistle-Smith?’

‘But of course,’ she said, sweeping Morley away from me. ‘Let’s go together, Mr Morley.’

I breathed a sigh of relief, apologised to the poor schoolmaster, and followed Morley and Mrs Thistle-Smith at a discreet distance.

I needed fresh air. Morley needed calming.

The plan worked. Straight away, Mrs Thistle-Smith engaged Morley in hushed conversation. There was the sound of bubbling water in the stream down past the croquet lawn. The evening sun flecked the lawn with emerald greens. The sky was cloudless. I stood by the house, smoking, as they wandered slowly along the borders of the garden. I couldn’t make out everything that was said, though snatches drifted towards me.

‘… and that is a Carmine Pillar I’m growing on the old apple tree … a thornless pink Zephirine Drouhin … the Japanese Rugosa Single Pink … ten feet high.’

‘You have a talent,’ I think I heard Morley say. Something something something … ‘Very special.’

It was refreshing, I think she said, to find a man who appreciates … something. A garden?

‘Sometimes I think my husband would hardly notice …’ Unintelligible … Something.

I watched from a distance as Mrs Thistle-Smith went to light a cigarette. Her match blew out. She went to light it again. I saw Morley move to light it; he kept matches about his person at all times, in case of emergency. As she held up her cigarette to her lips I thought I saw a slight ring of bruising around her wrist, but I may have been imagining it – the distance, the play of light and shade.

‘Thank you, Mr Morley, that’s …’ I think she said gallant. Mrs Thistle-Smith drew deeply on her cigarette and they turned slowly and began making their way back towards the house. ‘You don’t smoke?’

Morley seemed to agree that he did not.

‘Which makes your gesture all the more generous.’

‘Smoking is … a habit I have never acquired,’ said Morley, rather disingenuously, I felt, since he was one of the country’s leading anti-tobacco campaigners.

‘It’s a habit that I’m afraid has completely defeated me,’ said Mrs Thistle-Smith. ‘But they do say it’s good for the figure.’ She ran her hands lightly over her dress, pausing slightly and turning towards Morley. It was, as Morley himself might have observed – purely from a psychological and anthropological point of view, of course – a signal. From a distance – and it is of course difficult to judge these things from a distance, and it may be that I am interpreting events long ago with the unreliable aid of imagination, but nonetheless – these seemed like the first tentative steps in a complex and dangerous dance.

I feared for a moment for Morley’s rectitude and resolved to follow them if they turned and ventured any further away from the house and into the garden. But Mrs Thistle-Smith had clearly not entirely forgotten her duties as hostess, and they continued to retrace their steps towards the house. As they did so they paused for a moment at a clump of flowers – dictamnus, Morley later told me. And as they stood close together, studying the plant, Morley produced his matches, struck one, held it above the seedheads, which stood out in the evening light like little unhatched eggs, and there was a tiny flash of flames. Oils igniting, Morley later explained. Mrs Thistle-Smith was delighted by this display, and leaned in close to Morley in the flare, holding his arm for a moment. And this time Morley did not flinch in response. They stayed still for a moment.

As they approached the house I could hear Morley quoting Yeats.

‘“I will arise and go now, and go to Innisfree, / And a small cabin build there, of clay and wattles made; / Nine bean rows will I have there, a hive for the honey bee, / And live alone in the bee-loud glade.”’

This apparently thrilled Mrs Thistle-Smith even further, who seemed as enchanted by Morley as he clearly was by her. They both spotted me as they drew close. I ground out my cigarette.

‘Mr Sefton! We were just talking gardening,’ she said. ‘It’s so lovely to have a man around who appreciates a garden.’

‘I’m sure,’ I said.

‘I used to be able to talk to the reverend, of course,’ said Mrs Thistle-Smith. ‘Though he was rather keen on heather.’

‘Best for grouse, I always think, heather,’ said Morley.

‘Oh, my point entirely, Mr Morley!’ She touched his arm gently again with the back of her hand. ‘And so dull! I have a taste for the exotics myself. I have a banana plant down in the walled garden which is doing terribly well. Perhaps you’d like to come and see it sometime?’

‘Banana plant! I’d like that very much, Mrs Thistle-Smith,’ said Morley. ‘Do you specialise in the sub-tropicals?’

‘I wish!’ she said. ‘I think my garden might only ever be remembered for its borders. We are so blessed with our borders here, fifty yards apiece.’

‘Really?’

‘Yes. Not quite Gertrude Jekyll, but not far off. My mother planted them. We used to play among them when we were children, all of us. Running up and down. Racing, my sisters and my brother. Entirely without a care … I adore Gertrude Jekyll. Do you know her, Mr Morley?’

‘I know of her work, Mrs Thistle-Smith.’

‘Such wonderful ideas!’

‘Indeed.’

‘You know Gertrude Jeykll, young man?’ Mrs Thistle-Smith addressed herself to me, pretending at least that she was interested in my opinion.

‘I can’t say I do—’

She then turned her attentions straight back to Morley. ‘But tell me, Mr Morley, what is your philosophy of gardening?’

‘I would not presume to possess such a thing, madam.’

‘But you must! I’m sure you do! You are, after all, renowned for your ideas, Mr Morley.’

‘In all honesty, Mrs Thistle-Smith,’ said Morley, taking a small sigh, and gazing round at the beautiful garden before him, ‘I think all a garden really needs are a few magnolias in spring, some red-hot pokers in the summer, and an apple tree to be picked in the autumn. What matters is not so much the garden, but the touch, the care and the vision of the gardener.’

‘Ah yes, Mr Morley! How true.’ Then she turned and glanced – sadly, I thought – into the garden room, and remembered her responsibilities. ‘Now, you really must come and meet my husband.’

‘We have met, madam.’

‘Yes, of course … I should warn you, he can be very … forthright in his opinions. He’s from Grantham, you see.’

‘And nothing good ever came from Grantham?’

‘Some things, Mr Morley, I’m sure. But my husband has a healthy collection of bêtes noires. And I’m afraid newspaper journalists are one of them.’

‘I would be honoured either to confirm or confound his prejudices, madam.’

‘I’m sure you will,’ she said. ‘And then I’ll introduce you to the Talbots. Tom is an expert on the flora of the Middle East …’

![]()

By the doors leading into the garden the professor, in a black velveteen coat, was holding court like a great invalid king, seated on what appeared at first to be a gleaming throne, but which was, in fact, and quite simply, the only chair in the room – ‘A fauteuil,’ Morley later remarked, ‘French, possibly, eighteenth century, far too showy’ – lit from behind by the evening sun. He had his creamy white panama hat in his lap, like a Persian cat fed too many Yarmouth bloaters for breakfast, and a decanter of sherry on a viciously pie-crust-edged occasional table at his elbow, from which he repeatedly refreshed his glass. Mrs Thistle-Smith led Morley towards him, with me silently in their wake. As the professor turned and saw them approaching I noted the threatening look in his eyes – a very threatening look indeed. The look of a tyrant at a messenger bringing bad news. This was where our evening decidedly took a turn for the worse.

‘Darling,’ said Mrs Thistle-Smith, gently touching her husband’s arm, ‘this is Mr Morley, he’s staying at the Blakeney Hotel.’

‘An honour to meet you again, sir,’ said Morley. ‘It’s a lovely home you have here.’

‘An Englishman’s home,’ replied Mr Thistle-Smith, in his slow, damp voice, that seemed to leak with rancour as his wife’s burned with light.

‘And an Englishwoman’s,’ said Morley, rather gallantly, I thought, nodding towards Mrs Thistle-Smith, who smiled in friendly acknowledgement.

‘Swanton Morley,’ said Professor Thistle-Smith. ‘The man who’s putting our humble little village on the map.’

‘I can hardly lay claim to that distinction, sir.’

‘Oh, I think you can, sir. I think you can. Daily Herald. Tell me, Morley, do you regard journalism as a trade, or as a profession?’

‘I would hardly think it deserved the honour of being regarded as a profession, Mr Thistle-Smith.’

‘So, a trade, then.’

‘I suppose so.’

‘I see. And do you not think we have a tradesman’s entrance at this house, sir? Or do you suppose that we welcome our butchers and delivery boys here at all our parties?’

‘Darling!’ said Mrs Thistle-Smith. ‘Mr Morley is our guest. We invited him, remember?’

‘You invited him,’ said Mr Thistle-Smith.

‘I invited everyone!’ Mrs Thistle-Smith laughed, trying to make the best of what was already far beyond an awkward situation and was fast becoming a crisis. The little sherry-quaffing crowd around Morley and the professor was growing.

‘Anyway,’ said Mr Thistle-Smith, his voice dropping even lower, from bass to basso profundo, ‘seeing as you’re here, Morley, under whatever auspices, can I perhaps ask about your politics?’

‘You may, of course, sir, although I might reserve the right to remain silent.’

‘Darling, let’s not talk about politics,’ Mrs Thistle-Smith pleaded with her husband. She was playing nervously with the string of pearls around her neck. ‘We agreed.’

Mr Thistle-Smith ignored her.

‘You’re a Labour man, I take it?’ he continued.

‘What made you think that, Mr Thistle-Smith?’

‘Cut of your jib, Morley.’

‘A phrase that derives,’ said Morley, pleasantly, blithely, in characteristic explanatory mode, ‘if I’m not mistaken, from the triangular sail on a—’

‘I know what a bloody jib is, man! I’m not one of your readers in the Daily Muck.’

‘Darling!’ said Mrs Thistle-Smith, as now even more guests began to gather round the two men in anticipation of what was already becoming a bloody battle. Morley seemed oblivious.

‘Well, I’ll grant you then, I am a Labour man,’ said Morley.

‘Thought so.’ Mr Thistle-Smith sniffed and wrinkled his nose, as if suddenly detecting the unmistakable stench of a working man. ‘We don’t get many Labour men round here, Morley.’

‘I’m sorry to hear that.’

‘I’m not.’ Mr Thistle-Smith drew great stentorian breaths, as though emerging from deep water. ‘And if you don’t mind my saying, your first Labour government was a disaster. Except that taxis were allowed in Hyde Park.’ A couple of men in the crowd laughed, though why I wasn’t sure. ‘Which was of some benefit to those of us with … business in London.’ He looked cruelly towards Mrs Thistle-Smith, whose brightness and stature seemed to be diminishing by the second.

‘I see,’ said Morley. ‘And perhaps I can ask you about your politics, Mr Thistle-Smith? Would you mind?’

‘Why would I mind, sir? It’s a free country. At least at the moment it is. I am a Tory, born and bred, since you ask, and one of the silent majority proud still to believe in God, King and country.’

‘Though I think recent events perhaps suggest that we shouldn’t put our faith entirely in the British monarchy,’ said Morley teasingly. It was his way. I put my hands over my eyes.

Professor Thistle-Smith was, predictably, appalled.

‘Steady on, Morley,’ called a man in the crowd.

‘You’ll want to mind your tongue, I think,’ cautioned Professor Thistle-Smith. I was beginning to fear for Morley’s safety.

‘But how can I know what I say before I see what I say?’ said Morley.

I closed my eyes. I was getting a headache. Mr Thistle-Smith looked perplexed.

‘The White Rabbit, Alice in Wonderland,’ said Mrs Thistle-Smith.

‘Correct,’ said Morley.

‘I’m glad my wife can understand your nonsense,’ said Mr Thistle-Smith. ‘Because it makes no sense to me, man.’ He then launched into a passionate declaration of loyalty to the crown, ending with the words, ‘This country has relied for a thousand years on a strong connection between the people, their God, and their King.’

‘And queens,’ said Morley.

‘Obviously,’ said Professor Thistle-Smith.

‘The British monarch being crowned on Jacob’s Pillow. The Lion of Judah figuring on the Royal Arms. Potent symbols,’ agreed Morley.

‘Indeed. Indicating that ours is a Christian nation.’

‘I quite agree, sir.’

‘Good, and you would agree with me also then that the recent influx of non-believers can’t be good for the future of a nation like our own, and is in fact dragging us towards perdition itself.’

‘You’re referring to the Jews, Mr Thistle-Smith?’

‘I am referring, Mr Morley, to any person of any faith who enters this country without sharing or intending to share our common beliefs and habits.’

‘And how do you know what common beliefs and habits they share or don’t share with us?’

‘I know little and care less about the beliefs of other nations, Morley, and have little interest in finding out. But what I do know is that our whole country is being overrun by Freemasons and Jews and perverts and—’

‘I hardly think—’

‘I’ve not finished speaking, man. D’you not learn manners where you’re from?’

‘Clearly not the same manners as you were schooled in, Professor. I do apologise.’

Mrs Thistle-Smith leaned forward and whispered in her husband’s ear. As she did so, he shook his head, as if a dog attempting to dislodge a tick.

‘We have at least twice as many Jews here as we can possibly absorb, both of the oriental and the aristocratic type and as far as I’m concerned they are both equally unwelcome. England gave the world its three great religions—’

‘Really?’ said Morley. ‘Three? Christianity, Islam and Judaism?’

‘The Church of England. Quakerism. And the Salvation Army. Which should be enough for everyone, in my opinion. And if they’re not, and we don’t do more to prevent this influx of outsiders and unbelievers and to protect our institutions, then I believe we are heading for a social revolution, Mr Morley, with your sort at the vanguard.’

This stung Morley, as it was intended to do.

‘My sort?’

‘Darling!’ said Mrs Thistle-Smith, who was dismissed again with a wave of her husband’s hand.

‘And which sort would that be?’ continued Morley.

‘The little man,’ said the professor. ‘The self-made man.’

Despite the continuing unpleasantness and ferocity of the attack, and the now focused attention of all the other guests in the room, Morley continued to parry and joust.

‘The “little man”—’ he began.

‘One day that’s all we’ll have, Morley, if you and your like get your way. The bitter. The twisted. Look at the trouble you’ve been giving us in Spain.’

I was about to open my mouth, but Morley glared at me in warning.

‘I’m not sure that—’

‘We’re heading for a bloody revolution in this country if we’re not careful,’ continued Mr Thistle-Smith. ‘Like the French and the Spanish and—’

‘Realistically I think the guillotine is still rather a long way from Trafalgar Square, don’t you, Professor?’

But the professor was not listening. He was talking through Morley to the nation at large, and to his gathered guests.

‘I’ll tell you where this country started going wrong,’ he said, pouring himself another schooner of sherry.

‘With the General Strike?’ said Morley, preparing to defend territory he had clearly defended before. But Professor Thistle-Smith had a longer memory – a class memory.

‘No, no, no, sir. We have been slipping and sliding our way towards disaster for years. Decades. Since bloody Gladstone, in fact. Excuse my language, ladies. This country started to go wrong with the Hares and Rabbits Bill, if you ask me. When decent honest farmers aren’t allowed to shoot game on their own land the game’s up, as far as I’m concerned. Landowners are under attack everywhere in this country. Half of our fine homes and castles have already been turned into hotels and lunatic asylums. God himself only knows where it’s going to stop.’

Mrs Thistle-Smith took advantage of a natural pause in her husband’s outburst to interject.

‘Mr Morley also writes for The Times, darling. You like The Times.’

Professor Thistle-Smith waved his hand again. ‘Who he writes for is a matter of utter disinterest to me, frankly.’ He fixed his eyes – rather bloodshot, jaundiced eyes, I fancied, eyes long familiar with the half-lit cellars of a large country house – on Morley. ‘Like many of us here in the village, Mr Morley, I am only interested in why you’re asking questions about our dear departed reverend, and muck-raking in the gutter press.’

‘I have been trying to piece together a picture of the reverend’s final hours,’ said Morley.

‘An enterprise best left to the police, wouldn’t you say?’

‘The police certainly have their methods, sir. But I, you might say, have a motive.’

‘A motive? For the murder?’

‘Indeed, no.’ Morley seemed unconcerned by the accusation, which caused not a little excitement among those gathered around; there were mumblings and gasps. ‘But it is true that I did find the reverend’s body, with Mrs Snatchfold, during the course of my researches on my latest literary project—’

‘Ah yes, The County Guides!’ Professor Thistle-Smith laughed.

‘Which alas I have been prevented from working on until the police conclude their enquiry.’

‘A prisoner here in our little village.’

‘Effectively, yes,’ said Morley.

‘Well, I’m sure my wife will endeavour to make your stay here as pleasant as possible,’ said the professor vilely, glancing menacingly towards Mrs Thistle-Smith, a glance that seemed to indicate a gulf of long standing, infinite and unbridgeable.

‘Darling!’ Mrs Thistle-Smith looked shocked, as did many of the gathered guests.

‘What? A man not allowed to speak his mind in his own home?’

‘Yes, of course you are, but not if you are upsetting our guests.’

‘I think it might be time for us to leave,’ said Morley.

‘Not a moment too soon,’ said the professor.

![]()

‘And that,’ said Morley on our way to the hotel, ‘is why I don’t go to parties.’