Republic of Ireland Storytelling

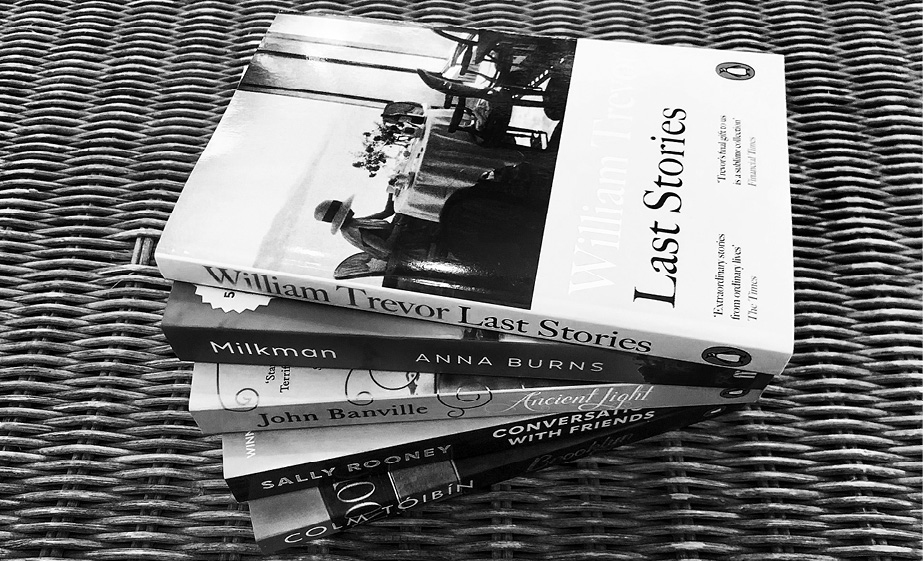

Bookstore in Limerick, Republic of Ireland.

Many countries have monuments and relics that people visit to seek support or inspiration. But only Ireland has a stone that hundreds of thousands of people a year bend backward and kiss in order to gain “the gift of the gab”: the Irish silver tongue that is something between eloquence, flattery, embellishment, and mythmaking.

Mystery surrounds the origins of the Blarney Stone, now located in the southwestern province of Cork, with its provenance variously attributed to figures as diverse as the biblical prophet Jeremiah and the fourteenth-century Scottish king Robert the Bruce. But there is nothing mysterious about what it has come to represent: the cornerstone of a national culture of storytelling for which Ireland and its populous diaspora is famous around the world—from the man in the pub to world-famous writers like James Joyce, Samuel Beckett, and now Sally Rooney.

With an Irish narrator, a story is never just a story. It is a living, changing thing: a tale destined to become taller with each telling, a format whose details change according to the context, the audience, and the person telling it. The truth is one thing, but far more important is the ability to stretch, twist, and uplift it into the creation of a memorable story, one that gets better every time it is wheeled out. In the narrative sense, blarney is never outright falsehood, but rather the truth of an event adapted and enhanced so many times that it has traveled some distance from the original. This is born not from a desire to mislead, but rather to entertain, and to embellish further with each new narration.

Storytelling is how the Irish talk their way through both the pain and pride of their past: a proud history that stretches back millennia, tinged with national traumas including the Great Famine of the mid-nineteenth century and the Troubles of the twentieth. Stories commemorate the past, keeping it alive and passing living memory from one generation to the next. And they help balm the still raw wounds of events that have left an indelible imprint on families, communities, and society as a whole.

Through storytelling, the tragicomedy at the heart of the Irish experience finds expression, creating humor out of bleakness. As Frank McCourt wrote in his memoir, Angela’s Ashes: “Worse than the ordinary miserable childhood is the miserable Irish childhood, and worse yet is the miserable Irish Catholic childhood… nothing can compare with the Irish version: the poverty; the shiftless loquacious alcoholic father; the pious defeated mother moaning by the fire; pompous priests; bullying schoolmasters; the English and the terrible things they did to us for 800 long years.”

Stories are an important window onto Ireland’s recent past, but also link back to more ancient traditions and culture. Seanchaí (traditional storytellers, literally “the bearers of old lore”) still keep alive an oral tradition that has transmitted history, law, and customs down the generations for over a millennium. Large tracts of Celtic folklore and history were transmitted not through being written down, but by these oral poets who passed the stories on to their successors. Stories are also part of how Ireland has knitted together the many different nationalities and cultures that have arrived on the island down the centuries.

Anyone who has ever heard an Irish friend or relative gather a group around them to tell a story knows the power of this tradition and its importance. Storytelling is about so much more than transient entertainment and amusing anecdotes. It is about connecting people and turning shared history (whether from last week or the last century) into something that bonds families, friends, and communities together. Stories unite us, engage the senses, and create something to believe in. Every individual, every organization, and every nation has its own story: in fact when you distill it down, often our story is all we have, the core foundation of our place in the world. We should all learn how to curate and tell ours, even half as well as the Irish do.