Wales Performance

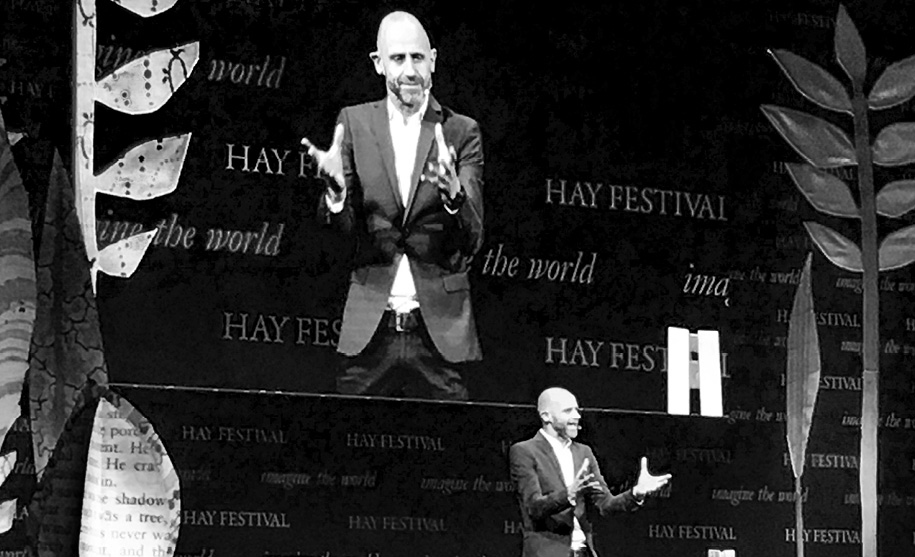

Evan Davis onstage at the Hay Festival, Hay-on-Wye, Wales.

Think of Wales and you think first of the voices. The voice of a choir in full swing, or a Cardiff rugby crowd reaching full pitch. The voice of Shirley Bassey or Tom Jones belting out a ballad. Of Katherine Jenkins or Bryn Terfel in full operatic flight. Of Richard Burton or Anthony Hopkins declaiming from the stage. Of Aneurin Bevan or Neil Kinnock hitting the heights of political rhetoric. Of Dylan Thomas cresting the airwaves with his poetry.

Welsh culture and identity are rooted in performers and performance. Whether it is a global superstar on the theatrical stage or the rugby field, or a male-voice choir or community rugby club, the act of coming together to perform in music, theater, sports, or politics is a cornerstone of identity. The Welsh national anthem reflects this participative, vocalist culture, variously describing a “land of poets and singers,” the “paradise of the poets,” and “the sweet harp of my land.”

It is through its performers that Wales has gained global renown and influence. Some of the most influential British politicians of the twentieth century were Welsh nationals who harnessed the Welsh spirit of performance to attract loyal supporters and advance the causes they held dear. Although it is Winston Churchill who has since gained precedence as the great wartime orator, in his time it was David Lloyd George, U.K. prime minister during the second half of the First World War, who enjoyed this esteem. Before becoming prime minister, his speeches played an important role in making the case for war to the people. He blended the humorous with the grandiloquent, rooting his rousing calls to duty and service (“the great pinnacle of sacrifice, pointing like a rugged finger towards heaven”) in the experience of his Welsh childhood, always holding the audience in the palm of his hand. “Lloyd George could send an audience rolling with laughter by just raising his eyebrows,” a friend later reflected.

The “Welsh Wizard’s” spiritual heir was the Labour minister Aneurin Bevan, a trade union leader who led the creation of the U.K.’s National Health Service and won renown as the greatest public speaker of his generation. Bevan too had the ability to make his audience laugh, cry, and cheer at will. Later came Neil Kinnock, who led the Labour Party for a decade, and though never winning power established his reputation as another memorable platform speaker in the great Welsh tradition. As with Lloyd George and Bevan, a Kinnock speech was an exercise in performance and personal history. “Why am I the first Kinnock in a thousand generations to be able to get to university?” he famously asked in a speech linking the British Labour movement to the cause of social mobility.

The political arena is just one in which the Welsh fire of performance burns brightly. A small nation has produced a surfeit of world-famous actors, singers, and performing artists: not distant figures, but global stars who had emerged from the same mine-working backgrounds as their homegrown fans.

Perhaps the most significant arena of all remains the rugby field, a proud area of Welsh tradition that has produced some of the most lasting national heroes and defining moments. Decades later, matches such as Llanelli’s defeat of the mighty All Blacks in 1972 are still commemorated and form a foundation of local identity and pride. There are few more significant dates in the Welsh calendar than the annual rugby match against England and the opportunity to earn cross-border bragging rights for the year. When these big games come around, the performance on the field is guaranteed to be backed up by the one off it, as tens of thousands of supporters combine to try and sing their team to victory. All rugby fans sing, but none perform and contribute to the match itself quite like the Welsh.

The Welsh performance culture is enshrined in an annual event that is Europe’s largest festival of competitive music and poetry. The National Eisteddfod, held every August, attracts thousands of competitors and around 150,000 spectators to a weeklong event of performances and awards, all in Welsh. The event has its roots in the twelfth century, and is the centerpiece for a tradition which is also enacted locally across the country.

Whatever the chosen arena, the Welsh understand perhaps better than any other the nature and significance of performance: the passion that drives it, the togetherness that delivers it, and the joy that derives from it.

This matters because performance is essential to success in almost every field, even if you are someone who will never pick up a musical instrument or sing in public. We all find ourselves in situations where we have to perform, seeking to persuade, to win support, or to inspire others around us. The great Welsh performers show how minds can be changed, causes rallied, and arguments won. Their art is universally important, one that we all can and should learn from.