Bhutan Happiness

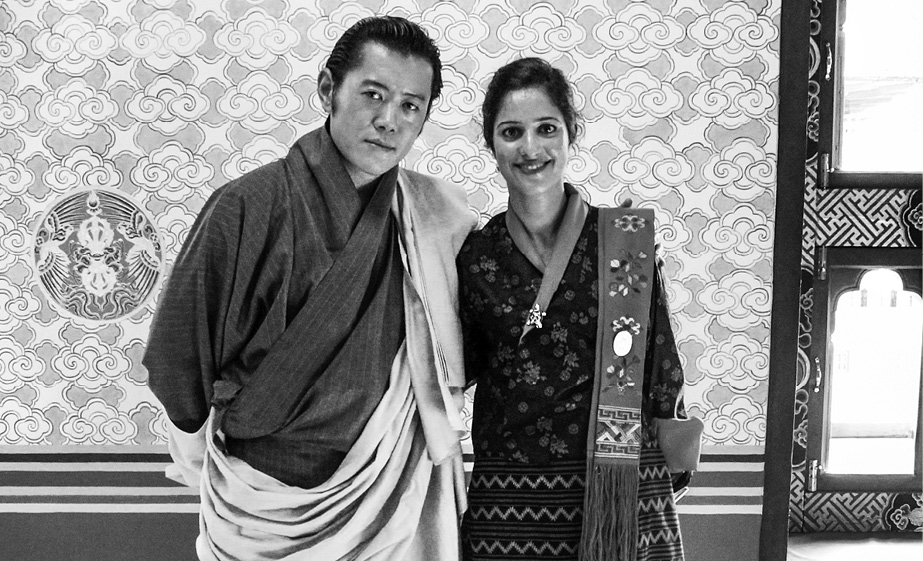

Dragon King of Bhutan–King Jigme Khesar Namgyel Wangchuck, Dechencholing Palace, Thimphu, Bhutan.

I promised 101 values, but there is one more I couldn’t possibly leave out: the Bhutanese example of how to achieve happiness. The idea of happiness perhaps feels less like a value and more of a fundamental right, but it’s something that comes up time and again in the workshops I hold. So have it as a bonus chapter here, and decide for yourself if happiness is going to be one of your defining values.

Happiness and positive psychology have only recently become a focus of study, and the one nation we have to thank for that, who brought it to the U.N. and to scholars as a pursuit, is the Kingdom of Bhutan.

Happiness is what most people say they value above all else because it just feels good, and research shows that when we are happy we are also healthier, more productive, creative, and have fewer conflicts. Yet happiness is difficult to attain because it requires so many of our needs to be met, balanced, and agreed upon by the wider system. In our meeting with His Majesty, Jigme Khesar Namgyel Wangchuck, locally known as K5 (the Fifth King), he explained how he saw it as the responsibility of the government to create an environment where its population can pursue happiness, and it is only since Bhutan opened its gates to the world in 1974 that we can begin to examine how they go about it.

Bhutan is a tiny Asian country with a fledgling economy, and one might expect it to pursue economic development, but they have seen that a common price to pay is the loss of one’s culture, environment, and social system. This is why Bhutan decided that gross domestic product (GDP) indicators are inadequate to address human needs and that it needed a more comprehensive indicator: Gross National Happiness. “We believe that the source of happiness lies within the self, and that there is no external source for contentment,” the King told me. “The faster car, bigger house, more fashionable clothes might bring you fleeting pleasure but not contentment.” As part of this approach, the Kingdom has been actively encouraging ruralization—creating amenities in countryside areas that encourage people to stay rather than make the default move into cities. You can see the impact of this reduced urbanization in that Thimphu is the only capital city in the world without a single traffic light. And you can see the importance of Gross National Happiness in decisions like the refusal to fully exploit Bhutan’s hydroelectric capacity—which could be commercially lucrative, but only at the cost of flooding valleys and forcing people to leave their homes.

Bhutan also shows the importance of having a higher purpose, whether that is religion, spirituality, or a philosophy of life. Bhutan remains a deeply Buddhist land and thus they have everyone’s well-being as their interest, not just their own. For this reason there are approximately seven thousand monks in the mountains of Bhutan, spending their lives meditating not only for personal development but also societal well-being. Often the eldest son of a family will be offered to the monastery at age five, bringing great prestige to his household.

Bhutan, the last Shangri-la, nestled in the Himalayas between the giants of China and India, is not intimidated, but rather lives according to its own terms, hence it is one of the few Asian countries that has never been colonized. The Druk or “Thunder Dragon” is the national symbol and appears on the flag of the country, and the jewels it is holding represent a different kind of “value.” Bhutan is aware that there are many human needs that have to be met for human happiness, not just the material ones. Similarly, positive psychologists encourage finding fulfillment through having goals that are interesting and enjoyable to work on, and that use our strengths and abilities.

Good governance is important to the Bhutanese. This is why His Majesty Jigme Wangchuck, the world’s youngest head of state, was given the throne in 2006, at age twenty-six, by his father, who wanted to groom him as a leader on the job. As king and head of the government he must take a long-term view that ruling parties can lack. He says, “I pray that while I am but king of a small Himalayan nation, I may in my time be able to do much to promote the greater well-being and happiness of all people in this world.”

The greatest lesson is that the pursuit of happiness does not work if pursued at an individual level. It’s about our relationships and how we help each other. It’s about us, all of us, together. It’s about having a cause greater than ourselves and improving the world in which we live.