Peter’s mother and father courting before their marriage.

CHAPTER 24

Shopping and the ‘Bloodhouse’

Shopping was part of our war. The Women’s Weekly advertisements all had military themes. I hated Vegemite, but I loved this advertisement: ‘Vegemite is with the Troops – He’s doing his bit for his dad.’ The picture showed a kid about my size wearing a slouch hat that I wanted. How can I get one like that?

Sully’s grocery shop was on the corner of Albion Street and Burnell Street; Nana and Grandpa lived at number 63 Burnell, only three minutes away, and we lived on the north side of Albion Street, about 10 minutes’ walk. The shop was just a little house where Sully lived, the business in the front room, and a storeroom behind. Painted on the big outside wall was an old-fashioned sailing ship with three masts and lots of shiny white sails. It was an advertisement that said, ‘Out of the blue comes the whitest of wash – Reckitt’s Blue’. Nana always used it in her copper with the whites and said it did a good job, but Mum reckoned it was a waste of money.

Whenever we went to Sully’s, which was about twice a week, I had to endure her commenting on my long eyelashes and big feet. ‘Just look at those eyelashes, Mrs Jones,’ she’d say to her customer. ‘Just wasted on a boy. Turn your head so Mrs Jones can get a proper look. And show her your feet. You could be a policeman with those.’ I’d blush from her attention. ‘Look at you, red as a beetroot.’ Having red hair and freckles was part of the problem. I could have wished for plain old black or brown hair.

Despite this embarrassment, I enjoyed Sully’s shop because of the biscuits. They came in big tins packed in neat rows like soldiers on parade. Customers could help themselves to a selection, put them in brown paper bags and she would weigh them. Mum bought cheap ginger nuts that were rock hard and lasted a long time unless dunked in tea. Sometimes Mum bought Teddy Bears that I thought were childish and virtually tasteless, and you could forget the Marie’s and Milk Arrowroots.

My excitement was Sully’s broken biscuit tin which was real treasure for me; she used to let me choose a couple for free. I never knew what I might find – fig slices, shortbreads or even a piece of chocolate biscuit. CHOCOLATE! Some people actually bought biscuits coated in chocolate. Chocolate was an incredible luxury in my life and a chocolate frog a treat to fondly remember. A jar containing chocolate frogs featured on the counter of every lolly shop waiting to tempt a mum with a sharp-eyed kid – a penny and guaranteed peace and quiet. We were too frugal for chocolate biscuits. Everyone we knew was poor except for my Catholic grandmother, and the bloody Yanks.

Mum liked Sully’s. She’d been going there all her life and Sully was always good for a little credit to get us through to payday. Mum would buy what she called ‘the necessities’. We’d ignore the expensive bacon, but perhaps get a tin of sardines that Mum liked to mix with lemon juice and pepper and spread on toast. Potatoes and onions were the mainstay. We’d get our ration of butter and tea using the coupon book.

Mum hated that the ration book included her age. She was rather sensitive about ‘approaching 30’. Particularly now that she was partying with sister Roma, 12 years younger, and Pearl, not much older. With the Yanks she liked to give the impression she was a child bride. It seemed that not only was I premature, I was born the son of a teenager.

The next shop up Albion Street from Sully’s is the butcher Mum flirts with. But when she’s got no money and feeds us soup, it’s me she sends to get ‘some dog bones’, even though the butcher knows our dog has disappeared. Shoppers plan their menus around meat, it’s an essential ingredient even though it’s expensive. The butchers are funny men who make the women laugh with naughty jokes about meat and how they can please their husbands.

Next door is the newsagent, where I’d love to buy a comic, but Mum says they’re trashy and a waste of money. There’s a woodyard with a really high fence so no-one can steal anything. They sell rounds of wood that you need an axe to split. That’s what Grandpa uses. Sometimes they’ve got mallee roots that Mum says burn really hot but cost a lot. Occasionally they have coal, coke and briquettes.

At the greengrocer, Mum buys me a piece of fruit for each day of the week, usually apples, oranges and bananas, although I have tasted cherries, grapes, plums, pineapple and once a disappointing coconut. We buy tomatoes and lettuce in season, and sometimes beetroot and cucumber that Mum makes into a yukky salad with vinegar and onions.

Fruit and vegetables are in short supply because of US army demands. ‘It’s a bit thick us having to feed a million Yanks,’ Grandpa says, but we all know there’s a war on. The newly formed Garden Army is planting vegetables in parks and along the banks of the Yarra River. Householders are urged to plant gardens. Nana has a beauty.

Our garden consists of a nectarine tree, two rhubarb plants, a couple of struggling geraniums on the front fence, and a quarter of an acre of long grass, weeds and burrs. The rhubarb is ready to pick two or three times a year; Mum stews it with white sugar. It’s her only dessert. And even though it’s a bit tart and leaves my mouth feeling furry, I look forward to it.

Sometimes, instead of shopping at Sully’s, we’d go up to Sydney Road on the Albion Street bus. It was a major shopping centre where they sold clothes and furniture as well as food. Mum wouldn’t be seen dead buying her clothes there. ‘It isn’t fashionable,’ she said. ‘No class, it’s just the road to Sydney.’

One Friday Nana came with us, and she and Mum both had their big cane baskets and two string bags each as well as their handbags. For me it was a real treat to go for a bus ride. I asked Nana if we could go down the back so I could stand on the seat between them and look out the big window. If I’d just been with Mum, we would have sat near the door and I would have had to sit up straight beside her and be good. Mum was nicer when Nana was with us.

In the shoe shop we found the pair of black shoes I needed and the salesman proudly asked us to follow him to the X-ray machine to check the fit. We’d never heard of this new invention before. It was like a big cupboard with three viewfinders on top. I went up a couple of steps in the middle while the salesman went to a viewfinder on one side and Mum, the other.

It was incredible, I could see all the bones in my feet. They were green and I could even see the edge of the shoes around the outside. I wiggled my toes and the salesman said he could see the shoes were the correct size and stepped aside so Nana could have a look. ‘That’s amazing,’ she said. ‘Who would have thought? Wiggle your toes again, Peter.’ It was good fun and I kept playing with the machine while Mum went to pay the bill. The salesman took her money and put it in a little container that he attached to a wire which zoomed it up to an office under the ceiling. There a lady made change and entered the sale details in a ledger before sending it back to the salesman. Reluctantly, I left the X-ray machine, but I’d had a good 10 minutes playing with it.

We went to the butcher’s and got meat for the weekend and checked out the specials in the fruit and veggie stores. Then we were ready for the good bit as far as Mum was concerned. Sydney Road might not have been fashionable, but it did have a pub – the only place in our district one could buy a cold beer or get grog to take home. It was called the Albion Hotel, but to Mum it was ‘The Bloodhouse’ because of all the fist fights. It wasn’t even a little bit fashionable and the crowd was pretty rough, but Mum was prepared to make concessions for a decent drink and perhaps be lucky enough to get a bottle or two of rationed Melbourne beer to take home with her usual dry sherry.

I remember The Bloodhouse for the noise, heat and cigarette smoke. I sat with Mum and Nana at a wobbly little table nursing a lemon squash while Nana had a shandy and a cigarette. I’m surprised to see Nana being naughty. Mum told her that smoking and drinking were sophisticated, showing she was a modern woman, entitled to drink in a pub like men. ‘It’ll do you good,’ Mum assured my nana. ‘He’ll never know. Just eat a peppermint on the way home.’

It was hard to get Mum out of the pub once she’d had a few, but Nana finally convinced her she had to get home to water her garden before making tea for Grandpa. Mum couldn’t have cared less about tea; she was a picky eater and never bought enough food. She could not imagine a little kid like me wanted more to eat than she did. I always felt starved. My hunger overwhelmed me. It was an obsession. Laurie could always have something to eat when he was hungry – yummy bread and jam. His mum would sometimes give me a thick slice and load on the plum jam. I loved it, and didn’t care if my teeth did rot.

Mum taught me how to make my own breakfast. I’d be five next year and ready for big school, so it was time I learned to look after myself. My ration was two Weet-Bix with milk and sugar. In summer the milk would be off after being delivered at dawn and sitting in the sun until Mum got up. She used to force me to drink it. However, now I was in charge, I could have breakfast earlier instead of waiting hours until she got out of bed, but I had to be very quiet. Mum hated to be woken – threatened to kill me if I did. I learned to walk on the balls of my feet and develop the stealth of a Red Indian like in the cowboy movies. I could put a spoon in a bowl without even a click. The same with doors. I learned to move like a ghost. Anything was better than waking Mum.

Tea time had its dangers. Mum had always been drinking by then. If she had been out all day there was a strong likelihood she’d gone to The Bloodhouse and be pretty drunk. If she’d been home alone, she’d have got into the dry sherry. There was always a bottle or two in the kitchen. It was part of dinner – a staple like pepper and salt, more important than bread and milk.

Peter’s mother and father courting before their marriage.

Father holds Peter aged 3 months.

Mum was proud of Peter’s curls and had this first birthday studio photo taken.

Peter gets a trike for his second birthday.

Peter, Mum and Dad who now displays his corporal stripes.

Mum and her friend go grocery shopping with Peter in his stroller.

Peter loved this sweater his nana made and wore it even on hot days. Wool was expensive and his nana unpicked other garments to knit it.

Peter aged 4 years and 8 months. Dad, home on leave, mows the lawn.

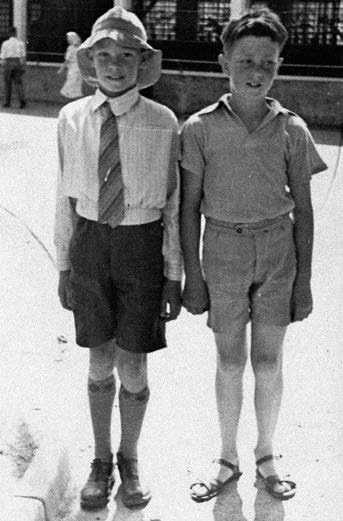

Peter, aged 4 with Pearl, his next-door neighbour.

Peter wears his own air force uniform.

Peter’s dad is promoted to RAAF Sargent. He is in the front row, far right with his RAAF crew.

Liberators lined up in Tocumwal.

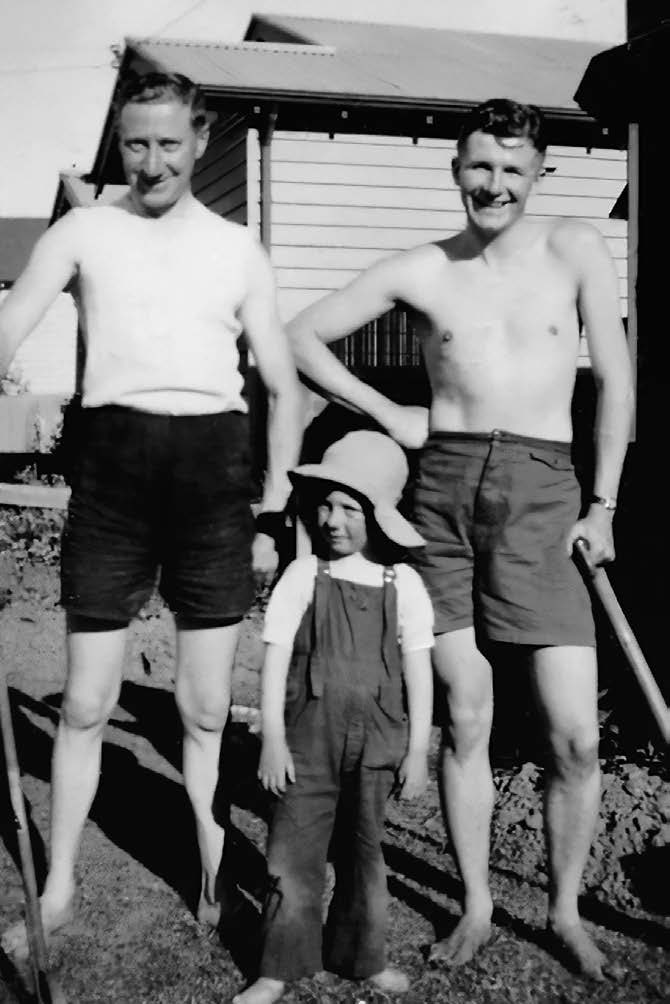

Dad and his mate dig a bomb shelter in the back garden. It filled with water the first time it rained.

Peter wearing his tin hat and riding his trike with sidecar. Prince, the spaniel, is the passenger.

A picnic on the Murray River at Tocumwal. Peter is on the mudguard of the American air force staff car beside his mother (right of picture).

Grandpa, Nana, Mum and Peter on a country outing in a RAAF truck.

Peter, Mum and Dad, now a Lieutenant, pose at Circular Quay for a street photographer.

Mum takes Peter and Laurie to the first post-war Melbourne Show.

Peter wears his new Xavier uniform.

Mum’s ‘black-eye hat’. Dad gives Mum 10 pounds after blacking her eye in a row.

The Ford Prefect takes the family on a tent holiday to Gippsland, Victoria.