This chapter discusses the sectarian violence that erupted in Belfast after the funerals of Lieutenant Colonel Smyth and Inspector Swanzy who had been shot by the IRA. To some extent provoked by these and other IRA attacks, the mood of Ulster loyalists and Orangemen was whipped into a frenzy by the re-organisation of the Ulster Volunteers and the rhetoric of Sir Edward Carson. A protracted campaign of terrorism, which became known as the ‘Belfast pogroms’, continued for two years and resulted in 470 people being killed, the majority of them Catholics.

If the Black and Tans were ruthless, they were surpassed in their violence by the Auxiliaries, former British Army officers under the command of Frank Percy Crozier, who arrived in August 1920 to act as an aggressive gendarmerie against the IRA. Reprisals continued into the autumn. Following the IRA shooting of a policeman, 150 drunken members of the Black and Tans sacked and destroyed the town of Balbriggan in Dublin. In County Clare, the IRA ambushed the police at Rineen, and the reprisals carried out by the British saw four towns suffer a night of burnings and killings. Meanwhile, communications between IRA GHQ and the country were maintained by Cumann na mBan who ran an effective postal service throughout Ireland.

BELFAST ‘POGROMS’

In 1688, Prince William of Orange, together with his wife Mary II, acceded to the Crowns of England and Scotland, deposing the Catholic King James II, who was Mary’s father. Thus began the Williamite–Jacobite War, which culminated in a famous battle across the River Boyne near Drogheda, in County Louth. Protestant King William III or ‘Dutch Billy’ won a famous victory over James on 1 July 1690. The Pope at the time, Alexander VIII, supported the Protestant king and had Te Deum hymns of thanksgiving sung in the Vatican when he heard that William had been successful. James, on the other hand, was unpopular even with the Irish Catholics who called him ‘Séamus a’ Caca’, which translates as ‘James the Shit’. While it was not a sectarian battle, it became a sectarian victory. The Loyal Orange Institution, or Orange Order, founded in 1795 to maintain the Protestant Ascendancy, traditionally celebrates the battle on 12 July, the discrepancy in dates resulting from the later adoption of the Gregorian calendar in 1752.

While Orange parades in Belfast on ‘The Twelfth’ had at times passed peacefully, in 1920 tensions were high. The IRA had acted more in a defensive capacity in Belfast, knowing that even the smallest action on its part brought massive retaliation against Catholic communities. Unemployment was high and there were many former soldiers of the British Army who were idle. Moreover, many Loyalists were incandescent with rage at actions of the IRA.

A popular Loyalist leader, Edward Carson, one of the founders of the Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF), gave a dangerous speech in Belfast on 12 July 1920, in which he said, ‘We in Ulster will tolerate no Sinn Féin.’ He further stirred the emotions of the Orange crowd with a clear threat to the nationalists, saying, ‘we will take the matter into our own hands.’ A week later, on 19 July, Derry was the scene of terrible riots against Catholics. The following day, in Banbridge, County Down, the funeral of Lieutenant Colonel Gerald Brice Smyth caused more violence. As we saw in Chapter Five, Smyth had been shot by the IRA in Cork for his infamous Listowel speech. After his funeral, Catholic homes and businesses in Banbridge were attacked and burned.

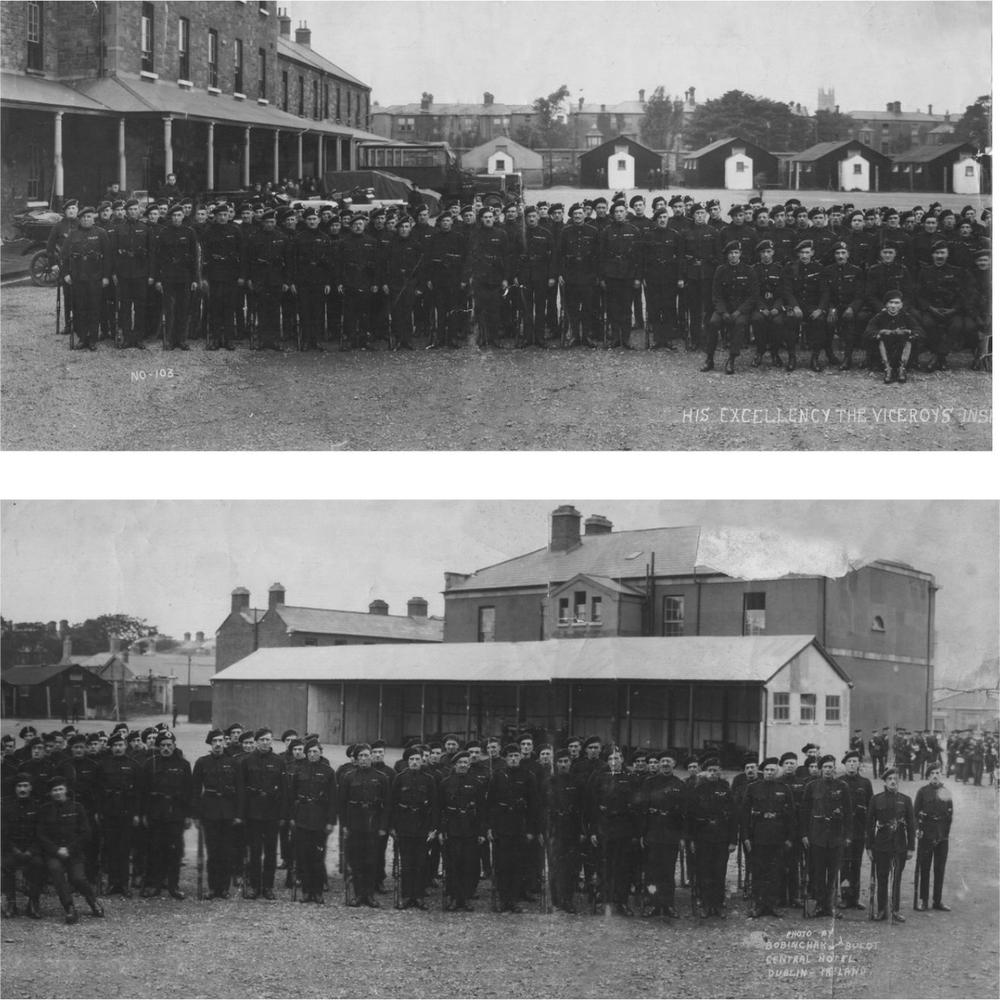

Members of the IRA Northern Division pose for a photograph.

On 21 July, Protestant shipyard workers gathered at Workman and Clark’s at lunchtime for a meeting organised by the Belfast Protestant Association. Following rousing speeches, Protestant workers formed a mob and turned on their ‘Sinn Féin’ co-workers. The Inspector-General of the RIC reported that the Catholic workers were hunted, severely beaten and thrown in the water. Men had their clothes torn to see if they were wearing rosary beads.1 Burning hot rivets, nuts and bolts, or ‘Belfast confetti’, rained down on workers, simply because of their religion. Any Protestant workers, some of whom were socialists, who tried to defend the Catholics were immediately branded as ‘Rotten Prods’ and beaten and expelled from the shipyards. Three days of sectarian rioting ensued. Over 7,000 workers were expelled from the shipyards, most of whom would never return to work there. For the next two years, a spark was all it took to reignite what came to be known as the ‘Belfast pogroms’ — sectarian murders and violence against a sector of society because of their religious affiliations. In the two-year period 1920–22, 470 people were killed, nearly 60 percent of whom were Catholic, although Catholics made up only 25 percent of Belfast’s population.

THE AUXILIARY DIVISION OF THE ROYAL IRISH CONSTABULARY

As discussed in Chapter Five, Winston Churchill, Secretary of State for War, had been responsible for the arrival in Ireland of the Black and Tans. He also suggested that a ‘special emergency gendarmerie’ was required to help police Ireland. General Nevil Macready, as Commander-in-Chief of the British Army in Ireland, rejected the idea, but Lieutenant General Tudor, the ‘Police Advisor’ in Dublin Castle, liked it. Known as the Auxiliary Division of the Royal Irish Constabulary (ADRIC) this new force consisted of former British Army officers. The ‘temporary cadets’ or ‘Auxies’, who wore distinctive glengarry hats, were to act as aggressive counter-insurgents and bring the fight to the IRA.

Although their initial training period seems minimal at six weeks, it was soon reduced to six days. Over the course of the war, 2,100 Auxiliaries signed up for duty but their total strength by the time of the Truce was about 1,500. Under the command of Brigadier General Frank Percy Crozier, they were divided into nineteen companies, named after letters of the alphabet and scattered around Ireland. They were very well armed and carried machine guns, Lee-Enfield rifles and revolvers, which they wore low slung around their waists in the fashion of North American cowboys. Their wage of £1 per day was twice as much as the Tans earned and nearly three times as much as an RIC constable. Nonetheless, they seemed to enjoy a policy of not paying for anything while they were in Ireland, with countless reports of the Auxiliaries spending days drinking in hotels and simply refusing to pay for their drink.

Members of the Auxiliary Division of the RIC at Beggars Bush Barracks. Under the command of Brigadier General Frank Percy Crozier, the Auxies were well armed and well paid.

The Black and Tans were often blamed for the excesses carried out by British forces in Ireland, such as Bloody Sunday at Croke Park in November 1920 or indeed the Burning of Cork the following month. In reality, it was often the Auxiliaries at the forefront of reprisals, followed by a mixture of Black and Tans and RIC. There was a tendency to lump them all together, under a sort of catchall term, ‘The Tans’.

POLICE COMMANDER H.H. TUDOR

Sir Henry Hugh Tudor was a lieutenant general who had commanded the artillery of the Ninth Scottish Division and planned the first large-scale tank battle in the First World War. Small of stature but plucky, Tudor was known for being on the front line of battles. He cared little for authority but was a personal friend of Winston Churchill’s. On 15 May 1920, Tudor was made ‘Police Advisor’ in Ireland. When the RIC Inspector General, Thomas James Smith, retired in November 1920, Tudor essentially took over his position.

Tudor was unsure of his position as ‘advisor’, and his inexperience of policing gained him few friends. He attempted to control the Dublin Metropolitan Police, the Royal Irish Constabulary, the Black and Tans and Dublin Castle’s intelligence network, which was a heavy burden. Ultimately, his inability to control the reprisals and murders carried out by his forces earned him the opprobrium of the press and the people of Ireland.

AUXILIARY COMMANDER FRANK PERCY CROZIER

Frank Crozier spent most of his childhood at the homes of relations in Ireland. At the age of nineteen, he fought with the British Army in the Second Boer War and later served in Nigeria. Having emigrated to Canada in 1909, he returned a few years later to campaign against Home Rule and he became a commander in the Ulster Volunteers, the unionist army founded in 1912. When war broke out in Europe, he fought with the Thirty-Sixth Ulster Division and was later promoted to Brigadier-General. On 3 August 1920, he assumed command of the Auxiliary Division of the Royal Irish Constabulary.

SHOOTING OF DISTRICT INSPECTOR OSWALD ROSS SWANZY

At the beginning of August, instructions were given to the IRA for the execution of District Inspector Oswald Ross Swanzy who had been indicted by a jury for the murder of Lord Mayor Tomás MacCurtain earlier in the year. Swanzy had been moved from Cork to Lisburn for his own security. ‘Lisburn is a small market town with a predominantly Protestant population … At this time a state of tension prevailed, Catholics had been beaten and others threatened and information was therefore difficult to obtain about the police movements.’2 Roger McCorley O/C First Brigade, Third Northern Division, recalled that he and his Belfast comrades, Thomas Fox and Seán Leonard, were joined by Sean Culhane and Dick Murphy from Cork in a mission to ambush Swanzy after he had attended church on Sunday, 22 August. Whilst Leonard kept the getaway car (his own taxi) running, the other four armed IRA men waited outside the chapel.

When Swanzy was spotted, the first shot was fired, as agreed, by Sean Culhane using Tomás MacCurtain’s revolver, which had been brought up from Cork.3 As the IRA delivered a further volley of shots, a large crowd of angry church-goers began to pursue the gunmen. McCorley halted and fired into the mob. He was then ‘attacked by an ex-British Officer called Woods who seemed to have plenty of courage’. Woods assailed McCorley with a blackthorn stick but ‘by a fluke’ McCorley ‘shot the stick out of his hand’. Luck continued on the side of the IRA when the police gave chase in a car and one of its wheels came off. However, Seán Leonard’s luck was short lived. He had devised a cover story to say that the IRA had hijacked his taxi but the police became suspicious and Leonard was eventually sentenced to be hanged for the shooting of the District Inspector. His defending barrister Tim Healy took the matter up with Lord French and the sentence was commuted to twelve years.

For the small Catholic and nationalist community in Lisburn, the shooting of Oswald Ross Swanzy meant that ‘the pogrom was pursued with increased activity, practically every business and house of a Catholic in Lisburn being burned to the ground….’4 Belfast, meanwhile, was the scene of ten days of rioting, which resulted in the deaths of over thirty people. Dáil Éireann reacted by voting for a boycott of Belfast firms, in order to exert financial pressure on businesses to force them to seek a halt to the violence.

CUMANN NA mBAN

Of the 276 women who were active in the 1916 Rising, the majority were members of Cumann na mBan, which was founded in 1914. Their activities during the conflict from 1919 to 1921 were numerous and included first-aid duties, provision of safe houses, communications, fund-raising, propaganda, storing arms, spying and administrative duties. They were women of immense courage, dignity and strength of character. Brighid O’Mullane was responsible for setting up ‘a secret line of communications between Dublin Headquarters and each District Council by which despatches were carried.’ She explained how it worked:

For example, information from Athlone would be conveyed by a Cumann na mBan cycle despatch carrier to the nearest Cumann na mBan Company Captain on the route, who, in turn, would pass it on similarly to the Adjutant of Mullingar District Council. The latter would then take over control of the messages and ensure their safe and secret despatch to Dublin. In this way, most important intelligence work for the IRA was done by Cumann na mBan. The Cumann na mBan had various ways of collecting information; some of the girls, being employed in local post offices, were able to tap wires from police barracks.

Cumann na mBan ‘also stored arms and ammunition in safe dumps, and kept the rifles and revolvers cleaned and oiled. If required by the IRA, they were utilised to transport arms to and from the dump before and after engagements….’5 Historian Pádraig Óg Ó Ruairc notes that ‘Women undertook dangerous work transporting arms and explosives during the War of Independence but the only occasion that women were permitted by their male comrades to play a direct role in attacking the enemy appears to have happened during the IRA attack on Kilmallock RIC Barracks….’6 (see Chapter Five.)

THIRD TIPPERARY BRIGADE

On 12 September 1920, a meeting of the Third Tipperary Brigade was in session at a farm belonging to the Meagher family of Blackcastle. This brigade council was attended by three officers from each battalion, and the entire brigade staff was also present. They gathered in a ‘haggard’ normally used to store crops. Two senior IRA officers who were on their way to the IRA meeting, Edmond McGrath, Commandant of the Sixth Battalion, Third Tipperary Brigade, and his Battalion Adjutant, William Casey, ran into a patrol of Lancers from Cahir British Army Barracks. McGrath pretended to have a punctured tyre on his bicycle, which allowed him time to size up the situation. They cycled through the byroads to get to Blackcastle where they reported what they had seen to the Third Tipperary Vice-Brigadier, Seán Treacy, who assured them that there were plenty of armed guards protecting the meeting.

Just as Treacy said that, there was a commotion, as scores of British Lancers came galloping towards them. Tom Meagher immediately slammed a large gate, which forced the Lancers to dismount from their horses. Seán Treacy ordered the IRA officers to collect up all the IRA books and documents. IRA officers Jack O’Meara, Con Moloney, Arty Barlow, Tadhg Dwyer and Jerome Davin grabbed what they could and then dashed in various directions.7 Moloney unleashed a volley of shots in the direction of the British. Treacy quickly loaded his Parabellum (Luger pistol) and he also opened fire on the British. Jack O’Keefe recalled in his witness statement that this action of Seán Treacy’s enabled most of those present at the meeting to get away.8

The IRA men retreated as best as they could across the fields. Treacy stopped running every now and then and fired his pistol until the British ceased their pursuit. Three important men from the Third Tipperary Brigade of the IRA were captured in the event which became known in Republican lore as ‘The Blackcastle Races’: Edmond McGrath, Commandant of the Sixth Battalion, Séamus O’Neill who commanded the Second Battalion and Jack O’Keefe who was Adjutant of the Eighth Battalion.9 All three were sentenced by court martial to two years’ hard labour in English prisons.

THE SACK OF BALBRIGGAN

Balbriggan, a small town with a population of 2,200, situated twenty miles to the north of Dublin, witnessed a night of terror on 20 September 1920. Head Constable Peter Burke was celebrating his promotion to District Inspector with his brother Sergeant Michael Burke. The brothers, who were from County Kerry, had taken a taxi from Dublin, which they left outside while they went drinking in Mrs Smyth’s public house. There were several Black and Tans in the pub, and when the taxi driver went in to ask for his fare, he was abused by the police. Michael Rock, the local Commandant of the IRA, got word that the Tans and the Burkes were abusing the cabman and ‘terrorising everybody in the public house, and making the men go down on their knees and sing God Save The King!’10 Michael Rock, William Corcoran and John Gaynor armed themselves, entered the pub and ordered the drunken Tans to clear out. Instead of doing so, the Tans made a rush at the IRA men, and Rock was left with no option but to fire.11 Peter Burke was killed and Michael Burke was severely injured.

Destruction in the small town of Balbriggan, County Dublin, following a night of terror as members of the Black and Tans sought revenge for the deaths of two RIC men.

At least a hundred and fifty Tans who were quartered at Gormanston military barracks, three miles away, arrived that evening seeking revenge. Looting and burning ensued and terrified residents ran from their beds in fear of their lives. The Drogheda Independent recorded that ‘Clonard Street suffered most extensively and here some 20 houses of all type were set alight.’12 Twenty other houses and pubs and a hosiery factory, Deeds, Templers & Co., that employed a couple of hundred people were also destroyed by the rampaging Tans. Sinn Féin activists James Lawless, a hairdresser, and John Gibbons, a dairy farmer, were dragged from their beds and brought to the barracks. They were severely beaten and eventually brought out and shot on Quay Street. The Drogheda Independent reported: ‘As they lay on the ground, their bodies were stabbed again and again, even after the last breath of life had gone.’13 From 11.45pm to 5am, the Black and Tans terrified the town of Balbriggan. They then went to nearby Skerries, where they murdered another two men. Their reprisal policy and the destruction and violence they inflicted was recorded by the media and brought wide-scale condemnation.

RINEEN AMBUSH

The Mid-Clare IRA had intelligence that a police tender travelled between Ennistymon and Miltown Malbay, County Clare, every Wednesday morning. An ambush site at Rineen, two miles from Miltown Malbay, where there was a curve in the road, was selected. Of the eight companies in the Fourth Battalion, each was to supply seven men for the ambush planned for 22 September 1920. The IRA parties arrived before daybreak, and the plan of attack was explained by Battalion O/C Ignatius O’Neill who, with the assistance of John Joe Neilan, O/C, Ennistymon Company, allocated positions to the men. It was the intention to attack the tender on its way to Miltown Malbay. However, a wrong signal had been transmitted, and the phrase ‘Ford lorry travelling’ was interpreted as ‘four lorries travelling’.14 As the positions the IRA occupied were not suitable for an attack on a convoy, Ignatius O’Neill called off the attack. However, the IRA waited patiently to ambush the tender on the return journey.

The ambush a few hours later lasted less than a minute. In a barrage of fire, six RIC men were killed, including a member of the Black and Tans. When the firing was over, the IRA men quickly captured ‘six Lee Enfield rifles, six .45 revolvers, a couple of thousand rounds of .303 ammunition and some Mills bombs’.15

They also set the police lorry on fire. However, after a short time, they were surprised by ten British Army lorries, out searching for Captain Lendrum, a resident magistrate who had been killed by the West Clare IRA earlier that day near Doonbeg. They had obviously heard the firing and seen the smoke from the burning Crossley tender. The British placed a machine gun in position at the top of Dromin Hill and poured a steady stream of fire at the IRA. A small number of IRA Volunteers returned fire, and they managed to hold off the British for long enough to give their comrades time to retreat, suffering only two wounded.

Patrick Kerin, O/C Glendine Company, Fourth Battalion, Mid-Clare Brigade IRA, recalled the British reprisals: ‘After the Rineen Ambush, the British forces in the area of Miltown Malbay and Ennistymon ran amok. They burned and looted several houses in these towns and in the village of Lahinch, and also murdered a number of innocent persons, some of whom were only on a holiday in the locality.’16 The Town Hall of Ennistymon was set on fire. Tom Connole, the local secretary of the Irish Transport and General Workers’ Union, was dragged from his house with his wife and two young children. He was tied up and murdered on the street by the Tans, who then set his house on fire and threw his corpse into the flames.

Having looted Flanagan’s shop for alcoholic spirits, the RIC and Tans began to order people out of their houses, which they then set on fire. They captured and shot dead a fifteen-year-old boy, P.J. Linnane and also murdered a farmer called Joseph Sammon who was in Ennistymon on his holidays. Patrick Lehane, who had been one of the IRA ambushers earlier in the day, was burned alive when the RIC again turned their attention to Flanagan’s shop and set it on fire. Lehane had been hiding in the attic of the shop.17 A Cork Examiner reporter wrote that Miltown Malbay was ‘completely wrecked’ and that several houses had been burned to the ground. His report stated that Lahinch, Ennistymon and Liscannor ‘were also wrecked’ and that rifle fire went on from 11pm until 4.30am. Residents ran from the towns to seek refuge in the countryside. According to the Cork Examiner, the estimated damage in financial terms was £40,000.18

The night of terror in Miltown Malbay, Lahinch, Ennistymon and Liscannor strengthened the resolve of the IRA and the people of Clare who refused to be cowed by the British. Musing on the event, Anthony Malone, one of the IRA ambushers, said that there were two direct results: ‘The enemy became more hostile and active, but he used large convoys when travelling. The people became very much embittered against him and adopted a more defiant attitude towards the Military and the Black and Tans.’19 The Irish Independent reported that the Bishop of Galway ‘deplored the fatal outbreak at Rineen as both unwise beyond measure and a grave breach of the law of God, except, of course, if it occurred in lawful self defence’. He also, it was reported, ‘deplored and condemned the destruction of lives and property of innocent people perpetrated in reprisal by British forces, all the more because of its seeming toleration and encouragement by those who, as professing to govern, are bound beyond all else to protect life and property’.20

Notes

1. McGaughey, Jane, Ulster’s Men: Protestant Unionist Masculinities and Militarization in the North of Ireland, 1912–1923, London: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2012, pg.143.

2. Fox, Thomas, WS 365, pg.3.

3. McCorley, Roger, WS 389, pg.9.

4. Fox, Thomas, WS 365, pg.6.

5. O’Mullane, Brighid, WS 450, pg.13–14.

6. Ó Ruairc, Pádraig Óg, ‘The Women Who Died For Ireland’, History Ireland, September/October, 2018.

7. Ryan, Desmond, Seán Treacy and The Third Tipperary Brigade, Tralee: The Kerryman, 1945, pg.144.

8. O’Keefe, John, WS 1168, pg.10.

9. McGrath, Edmond, WS 1393, pg.13.

10. Lynch, Michael, WS 511, pg.144.

11. Rock, Michael, WS 1398, pg.12.

12. Drogheda Independent, Saturday, 25 September 1920, pg.3.

13. Ibid., pg.3.

14. Kerin, Patrick, WS 977, pg.10.

15. Malone, Anthony, WS 1076, pg.10.

16. Kerin, Patrick, WS 977, pg.13.

17. Ó Ruairc, Blood on the Banner, pg.169.

18. Cork Examiner, Saturday, 25 September 1920, pg.5.

19. Malone, Anthony, WS 1076, pg.12.

20. Irish Independent, Saturday, 25 September 1920, pg.4.