This chant, originally found within the Guru Gītā — a treatise on the importance of the guru — speaks to the essential wisdom every spiritual practitioner must know about the guru.

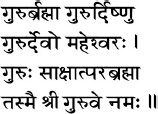

gurur brahmā gurur viṣṇu

gurur devo maheśvara

guruḥ sākṣāt parambrahmā

tasmai śrī gurave namaḥ

The guru is Brahmā, the guru is Viṣṇu,

The guru is Śiva [Devo Maheśvara],

The guru is nearby and the guru is everywhere.

To the guru, I offer all that I AM.

This is a wonderful mantra for setting the tone of a student’s mind-set. It is a great mantra to chant at the beginning of a practice to get into the vibe of learning and be open to new information. As such, this mantra can be used as an invocation for daily practice to keep a “beginner’s mind,” in practice and beyond, or it can be chanted at the start of a yoga class to encourage students to remain open to all the teachers who are present in their life.

To begin chanting, move through it one line at a time. Say gurur brahmā gurur viṣṇu, and move line by line from there. If teaching it to others, use a call-and-response method, going line by line, in order to make the pieces easier to remember and follow along. The last line, tasmai śrī gurave namaḥ, can be repeated several times. This brings home the intention of the chant to offer all that we are to the power of the teachers who are present in every form all around us.

This mantra honors the most sacred relationship in yoga, that between the teacher (guru in Sanskrit) and the student (śiṣya). Indeed, only through the transmission from teacher to student has the Vedic tradition been passed down through the millennia. But more importantly, this relationship contains the power to reveal the most fundamental and basic teaching, which is that we are all connected.

The mantra begins by naming the holy triumvirate of yogic mythology — Brahmā, Viṣṇu, and Śiva — who are the primary teaching forces within our lives. They are the gurus to whom everyone is a student. In the scope of a lifetime, these aspects appear to us in varied forms and lessons. The mantra also indicates that there is something beyond the beyond (parambrahmā) — indescribable — to which we are all intimately connected. Though indescribable and beyond our grasp, we can find this force within everything that appears near to us (sākṣāt). In this way, the guru appears to us in every form imaginable. Teachings show up within the circumstances of our birth and our parents, which is the realm of Brahmā. They appear in our life through our friends, colleagues, and social duty, in the realm of Viṣṇu. They accompany us through sickness and challenges as we face the end of all things and our own death, or the realm of Śiva. The principle of the guru is always nearby (sākṣāt), and it is beyond the expressible forms of the universe (parambrahmā).

Some spiritual aspirants find one teacher who leads them down the spiritual path, but all aspirants have a guru present at every moment of their lives, if we have the presence and openness of mind to see it. When someone challenges our moral sensibilities, when our parents invite us over for Thanksgiving dinner, or when our boss withholds a raise we feel we deserve, each of these moments holds an opportunity for us to see one of these guru aspects at work within our lives. We are able to recognize that within every single instant there is a chance to learn and grow.

The spiritual life is lived every moment of every day and arises as a practice in each and every choice we make. It doesn’t take yoga pants and mala beads to make someone a spiritual aspirant. It takes the tenacity of spirit and the presence of mind to consistently rise to every occasion and practice one’s spiritual calling, which is the unfoldment of the potentiality of one’s own soul. Like the knights of the Arthurian grail legends, each of us carves our very own path through the thickets of our internal landscape as we make our way into the deep inner recesses of the heart. There, we discover the treasure of our spiritual path: the guru within, who is the ever-present guide of the heart showing us the way to our own source of freedom. As we walk on this path, moment by moment, choice by choice, we offer all our efforts to this internal and eternal source of wisdom within us. In this way, no matter what stage of life we are in, we are never lost.

Every single one of us experiences the same three basic stages of life: birth, life, and death. These three stages are certain for every person on the planet, and the triumvirate of Brahmā, Viṣṇu, and Śiva preside over them, respectively. The gurus of birth, life, and death show us the value and lessons within the circle of life.

These three stages are found within every aspect of the universe. The universe itself had a birth, it will sustain itself for a period of time, and then it will die. This great cycle is reflective of all experiences in life — friendships, jobs, homes, families, income. Things begin, they last for a duration no one can predict, and then they end. Sadly, nothing lasts forever. This sentiment can be a blessing (when things are bad) or a curse (when things are good and we hope they’ll last). What do we do to exist comfortably within such a tumultuous, inevitable cycle of existence?

We use mythology to give us context and understanding of this inevitable pattern of constant flux. Mythology provides us with a container within which to place the challenging experiences of our lives. Otherwise, we can have difficulty coming to grips with them. The trick is to pay attention to the mythology as it unfolds within us and within the events of our lives. We can use these associations to understand the great wisdom of the time-tested Persian proverb, “And this too shall pass.”

Brahmā is the god of creation, and he presides over beginnings and our birth. Funny thing is, we actually have little control over these principles. As babies, our birth is a haphazard experience beyond our control. We come into this life with a prearranged set of parents and circumstances. Interestingly, Brahmā reflects this heir-apparent attitude with his own story. Commonly, it is said that he is self-born within a lotus that sprouts from the belly button of Viṣṇu, and from his four faces Brahmā utters each of the four sounds of oṁ ( ), which begins the creation of the universe.3 Another story says that he was born of a great golden cosmic egg that was floating around in the nothingness of numinosity. Again, he is almost self-generated without rhyme or reason. His job is to create the rest of existence, and he begins by creating ten sons from his mind, who help him design and construct the universe. When he feels lonely, he creates his beautiful daughter, the goddess Sarasvatī (Saraswati), by thinking the most pure thoughts possible. Each of his four faces represents the supreme knowledge of the four books of the Veda, and he carries no weapons because, for him, there is nothing to destroy, only unlimited potential to create.

), which begins the creation of the universe.3 Another story says that he was born of a great golden cosmic egg that was floating around in the nothingness of numinosity. Again, he is almost self-generated without rhyme or reason. His job is to create the rest of existence, and he begins by creating ten sons from his mind, who help him design and construct the universe. When he feels lonely, he creates his beautiful daughter, the goddess Sarasvatī (Saraswati), by thinking the most pure thoughts possible. Each of his four faces represents the supreme knowledge of the four books of the Veda, and he carries no weapons because, for him, there is nothing to destroy, only unlimited potential to create.

In fact, for us, our birth is a great mystery. We can’t remember it personally, except as a story told by others. We are thrust into this life like the mere thought of Brahmā, filled with unlimited potential. As children, all things are possible for us, or so we believe. When asked what we want to be when we grow up, we say doctor, lawyer, astronaut, ballerina, firefighter — anything we want. In our childhood, the world is our oyster. Like Brahmā, we believe we can create whatever our mind conjures.

But then something funny happens. We grow up, and the constraints and confines of society close in around us. We are fettered with the chains of “should” and “should not,” and filled with doubt instead of promise. We see that our minds do not make “reality,” which in fact makes its own demands upon us. We may come to feel small, weak, and incapable. Strange how, as we get bigger, the box we live in becomes smaller and smaller.

Harken back to childhood. Remember the dream that kept you awake at night and inspired imaginary play with friends? That dream and that child still lives within and is waiting to be reborn. The dreams of youth are profound, but the problem is that we cannot realize those dreams when we are young. We must reconcile our potential with the constraints of adulthood. We can only follow the path of our unlimited childlike wonder after we have broken out of the chains of immaturity. Given this seemingly unfair setup, it’s no wonder that there aren’t very many temples of worship specifically for Brahmā in India. He’s recognized as an equal ruler in the great triumvirate, and he is often included in common rites, but it is very rare to specifically worship him or seek his guidance. Because, in fact, what can we do to reconcile our birth and beginning except learn to live the experience as a fully conscious adult? And so, we turn to Viṣṇu, the preserving force of life.

Viṣṇu, as the preserving force of the universe, is the energy that maintains every aspect of the duration of our lives. His energy is present in our current relationships, our dynamics at work, and the personal growth we seek through spiritual practice. He is also abundantly present in anything that keeps us moving along. Any time we are in our “status quo,” Viṣṇu is there helping us to maintain it. And though he’s always present, his job isn’t rigorously creative like Brahmā or as creatively destructive as Śiva, and so he is often depicted at rest on his great serpent-couch, Ananta, in the great cosmic ocean of potential. We can imagine this scene: a blissful god lounging in an endless pool on a floaty device with a subtle grin on his face. Though it seems that Viṣṇu is doing little in this idyllic setting, he is hard at work dreaming, and his dreams become our waking reality. When god dreams, anything can happen. And sometimes wild and crazy things stir up the world so much that disaster strikes and we can’t quite handle reality on our own.

When this happens, Viṣṇu will incarnate and arrive on earth as a cosmic assistant (called an avatāra) ready to lend a helping hand to humanity. Any time the world is suffering from too much strife and sorrow, Viṣṇu will appear in bodily form and assist us back onto the path of dharma, or “duty.” Dharma exemplifies the way in which we express ourselves in the world. In a sense, it’s our life purpose. Therefore, Viṣṇu represents both the challenges that humans face as adults in the world as well as the source of fortitude and courage to meet those challenges successfully.

In the Puranic tradition of India, Viṣṇu has had at least ten incarnations, including as a fish, a tortoise, a dwarf, and several different men. Probably the most popular of Viṣṇu’s avatāra is his incarnation as Kṛṣṇa (Krishna), the blue-skinned flute-playing charmer who spends his youth herding cows in the bucolic lands of Vṛndāvana (Vrindavan).

Kṛṣṇa’s early life reads like a storybook. In the afternoons, after the cows have come home, he plays his flute in order to round up the cowgirls, with whom he dances into the night. But, like all of us, eventually Kṛṣṇa grows up and gets a real job. Youth makes way for the harsh reality of day-to-day life. His real job finds him driving a chariot into battle with the greatest warrior in the land, known as Arjuna. During his employment, he helps Arjuna overcome his doubt (which becomes the dialogue of the Bhagavad Gītā). Eventually Kṛṣṇa retires to hang out with his one hundred wives (that’s hard work!) and best friend, Uddhava.

Even Kṛṣṇa apparently once admitted to his best friend that, in order to be incarnate within a human body, he could only be as much as 15/16 perfect.4 Without that 1/16 of imperfection, his divine stature would lose hold of its human form. So, from a divine perspective, humanity is almost by definition imperfect. This is our great challenge, and it is also our great gift. Ultimately, meeting this challenge is the source of our own redemption. This happens when we accept our imperfections in order to behold the deeper truth of the greatness of our souls. And, though yogic wisdom tells us that our soul is timeless, as humans we still fear what happens at the end: our death.

The third aspect of this life-encompassing mantra is embodied by Śiva, the god of death and dissolution. His realm includes every sort of ending, from relationships and ideas to illness and physical death. Śiva is often vilified for this destructive role within the trinity. His incarnation is often portrayed with matted dreadlocks, scantily clothed, and covered in ash. He makes it his business to meditate like a true mendicant on top of a mountain in the Himalayas in order to realize the nature of reality, which is yoga, or union between the highest self and the numinous. The mythologies describe Śiva as the primordial yogi, at ease with the changeable nature of the universe, as he’s the deliverer of its end. That must make change easy for him, as one cannot be attached to something that one knows will inevitably die!

Of course, many people, particularly in the West, are not that comfortable with death. We don’t like to see it, and we don’t like to think about it. For many, aging itself becomes hard to contemplate, and some people try to avoid the appearance of aging at all costs. Other cultures embrace death and keep it in the forefront of daily life and ritual. For example, in India and in Bali, extravagant cremation ceremonies can last for days, even months, as people enact rituals that help them to celebrate the life and death of their loved ones.

Known as Maheśvara, the great lord Śiva is often treated like an unwelcome guest. But death is an integral part of life. Further, Śiva presides over the fires of transformation. With utter compassion, Śiva’s destruction clears a path for new possibilities and creates the space where anything can arise. Within us, Śiva can help to clear out old paradigms and belief systems to allow what is embedded deeply within our hearts and unconscious to rise to the surface. His energy can move through our life like a forest fire through the brush. Though undeniably destructive, it is also essential for providing the opportunity for new growth.

There once lived an old woman who had a dedicated spiritual practice to Lord Śiva. Daily, she would pray to Śiva and make offerings to him on her altar. In the quiet moments she would chant to herself Śiva’s favorite song, “Oṁ namaḥ śivāya,” and always had him at the forefront of her mind. She lived a meager existence and had very little, but she was happy in her simple devotional practices, which kept her busy every day.

One Sunday afternoon, it was time for her to go to the market, and so she gathered her shopping basket and headed off. She always went later in the day because the vendors would price their wares more cheaply and would be more apt to bargain. The woman had very little money and had to be very careful about what she purchased each week, as it would have to last. She made her way through the market, collecting the few items she needed for the week, and as she strolled past the fruit vendor, she spied a perfectly ripe mango set off on the side of the cart. Its ripeness was such that one more day would put it over the edge, but at this very moment, it was at its perfect peak. The vendor saw the old woman eyeing the mango and said, “Is this your favorite fruit?”

“Why, yes, it is, but I so rarely get the chance to have it.” The old woman licked her lips after speaking.

The fruit vendor took pity on the old woman and handed her the mango saying, “Here you go, old woman. Please enjoy it. I cannot sell it tomorrow as it will be overripe, and you are the last person here today. Take it as my gift.”

The old woman was overjoyed at his kindness and took the mango, carefully placing it in her basket. She walked home smiling to herself at the dessert she would enjoy that evening. Upon returning home, she set out her groceries and prepared a stew that would last her for the week. She added a few spices and some rice to thicken it up. When she was done, she poured a little bowl for herself and ate it, all the while staring at the mango. At the end of her meal, she cut the mango, but at the last minute, decided only to eat half. It was such a rare treat, that she set the second half aside for the next day, so that she could prolong her joy. She said her nightly prayers to Śiva and went to bed.

In the middle of the night, the woman was awoken by a knock at the door. At this time, in this place, rules of hospitality were paramount, so she got out of bed, put on her slippers, and answered the door. A very old, hunchbacked man with a cane stood before her.

“Hello, old woman! I’m sorry to bother you so late, but I have been walking very far and need a place to rest. Could I come in?” The old man shuffled past the woman as she opened the door a little more widely for him to pass. He looked around her tiny cottage and said, “My, my, it smells delicious in here! What were you cooking? Might I have some? I am so hungry and have traveled for so long.” The old woman obliged him and filled a bowl with her stew. She sat across the kitchen table from him and watched him slurp up his soup, while some dribbled into his long, white beard. When he was finished with his first bowl, he asked for another. And then another. After finishing his third bowl of stew — and the entire pot she’d made for the week — he stretched his arms up and surveyed her tiny hut.

“My, what a tidy, quaint place you have here! Oh, goodness, is that a mango I see on your shelf there? It’s been so long since I’ve had one. I sure would love something sweet to follow that delicious meal I’ve just eaten.” The old man patted his belly and smiled at the old woman.

Her heart pitter-pattered in her throat. The mango was her favorite, and she was so looking forward to eating the whole thing. She now regretted not enjoying all of it earlier that evening. As she had these thoughts of lack and selfishness, she caught herself, turned her mind to her beloved Śiva. She quietly said a chant to him and graciously offered the mango to the old man.

He ate it whole in one bite.

The old woman sighed, said another prayer to Śiva in her mind, and smiled at the old man. It was time to go to bed, so she offered him her own meager mattress and found a small spot in a clean, quiet corner for herself. Later, in the middle of the night, the old man startled her by shaking her shoulders saying, “Wake up! Wake up!” She awoke with a start and asked, “What’s wrong?”

She looked up at him. Suddenly his features changed and he grew to an enormous stature, throwing off his ragged cloak and revealing his true nature — it was Śiva himself! She recognized him immediately and prostrated before him.

“You bow to no one, old woman. Stand before me and prepare for your journey home.” Śiva reached out his pristine hand and lifted her up. She stood with him, hand in hand, and she smiled. He said, “It is because of your consistent devotion and your ability to offer all you have with your whole heart that you are coming with me. Your physical life is over, but your spiritual life is just beginning.”

Off they went together, merged as one.

As Śiva takes the old woman’s hand, her lifetime of continuous surrender is what allows her to step into the grace of this deathly lord. The old woman did not fear death because throughout her life she had consistently shed her expectations and her grip on what life “should be.” She let go of little things every day, accepted every “little death,” and so when Śiva arrived, she was ready to open herself to him and let go in the ultimate way.

Similarly, honoring Śiva in this mantra is a way of acknowledging this mysterious truth: that when we stop resisting death, and all the inevitable endings we encounter, we step more fully into the timeless flow of life. Death, after all, never truly ends the cycle of life, but is merely the cycle’s most transformative moment, for it is the gateway to resurrection. It’s like Albert Einstein says: “Energy cannot be created nor destroyed, it can only be changed from one form into another.” When we die to our old way of being (whether that includes fear, pride, anger, or resistance), we then shift our energy and open the door for a new way of being (one embodying openness, honesty, integration, and gracefulness). In every mythic story, the hero, like the old woman, must undergo a transformation, which typically involves a death of some kind. In fact, what defines the hero is the willingness to confront fear and doubt and, if necessary, die to overcome the story’s challenge. While heroes may have fear, they call forth the courage necessary to overcome it and walk their journey by living from this strength, which resides at the core of their being.

When we live from our own center, even when death touches us, we find courage (literally, the strength of our heart) to face our fear and allow death to bring forth new life. Too many of us ignore death, tragedy, aging, calamity, hard times, and even just the blues, when the secret is acceptance.

The old woman did this in the story. Her entire life was in service of death. She was able to embrace the god of death, Śiva, through her prayers and songs. It allowed her to be at ease with changing circumstances, disappointment, poverty, and personal challenges. It didn’t make those challenges go away. It made them easier to bear. What if, instead of denying the very real presence of constant change, death, and transformation in our lives, we went forth with courage and used our heart to stay at the calm center of any storm? This is Śiva’s gift. This is what he brings to the old woman on the night of her own death: grace through courage.

This release into transformation and the embodiment of acceptance of all the circumstances in our life is also what the last line of this mantra invokes: “To the guru, I offer all that I AM.” When we are able to see every moment as an opportunity to be taught and to grow, we give ourselves over to the teacher that is always present all around us.