The relationship between a teacher and student is a major aspect of yoga practice, and within several different Upaniṣad, we find the same mantra, which codifies the ideal nature of this relationship. This version of the chant is found in the Kaṭha, Mandukya, Śvetāśvatara, and Taittirīya Upaniṣad:

sa ha nāv avatu

sa ha nau bhunaktu

sa ha vīryaṁ karavāvahai

tejasvi nāv adhītam astu

mā vidviṣāvahai

oṁ śāntiḥ śāntiḥ śāntiḥ

May we both be protected

May we both be nourished by wisdom

May we work together with great energy

May our study be vigorous and effective

May we never experience enmity toward each other

oṁ peace, peace, peace

This mantra is an excellent choice as an invocation for any situation where both a student and teacher are present. The purpose of the mantra is to protect both parties in the relationship and ensure that each is focused on achieving the highest aim within their practice together. The mantra can either be taught by the teacher to the student in a line-by-line, call-and-response fashion, or both teacher and student can chant the mantra together. The end of this mantra includes the simple chant for peace that both teacher and student are encompassing in their work — peace on three levels: personal, mutual, and universal.

While yoga could be surmised as being all about relationships, it is clear that the most important relationship within yoga is between the teacher and the student. This bond is essential for spiritual growth and has withstood the test of time as the primary mode of dissemination for yogic and Vedic wisdom across five millennia. Only in the past few decades or so has knowledge about yoga become widely available through any resource other than the direct transmission of a teacher or guru. Even so, most modern-day yoga practitioners still get their yoga from teachers. Whether it’s the more direct transmission of a one-on-one relationship or the more modern interpretation of a group class setting, we still find most students sitting, listening, and taking in the knowledge of a teacher.

Still, the nature of the relationship is extremely important because it determines the quality of the work and, ultimately, one’s success. As this mantra exemplifies, it will ideally be a mutually beneficial relationship. There is no hierarchy or degree of subservience or domination. In fact, this chant is said by both the student and the teacher to clarify their uplifted intentions as they begin working together. In today’s world, this timeless mantra is of critical importance.

The term upaniṣad means “to sit near,” and the particular grouping of texts that became the Upaniṣad were indeed generally recounted in a story-like fashion, where the student learned directly from a venerable teacher. This was the basic tradition for millennia. Teacher would teach. Student would sit and listen. And through that perfect listening, the wisdom of the teacher would enlighten the student. Literally. This remains a great way to convey teachings, especially in an intimate setting, where the teacher and student can engage in question-and-answer dialogues. This way, the student asks the teacher what they most want to know, and the teacher responds directly and individually.

This is a great system for a few reasons. First, students ask questions only about knowledge they are ready for. This is because, as age-old wisdom tells us, we only ask questions for which we already have the answers. The teacher only reveals what the student suspects already. Second, when a student asks a question, the teacher knows the student is serious about learning. Traditionally, the student must ask three times before the teacher will give the answer. In this way, the teacher can be assured, as Jesus would say, of not throwing pearls to swine (Matthew 7:6).

The practices and the knowledge of yoga were kept pretty secret for millennia after millennia. There was a good reason for this. It was the care and discernment of the teacher, and their rapport with the student, that helped to direct the teachings in a way that would guide the specific student forward in his or her spiritual endeavors. When teachings are cast in a haphazard, careless way, they may do as much harm as good. Unprepared students may stumble onto teachings that make no sense to them, or worse, are misconstrued. Only a sympathetic, knowledgeable teacher can guide and steer spiritual understanding in a way that is personal, powerful, and appropriate to one’s own learning curve.

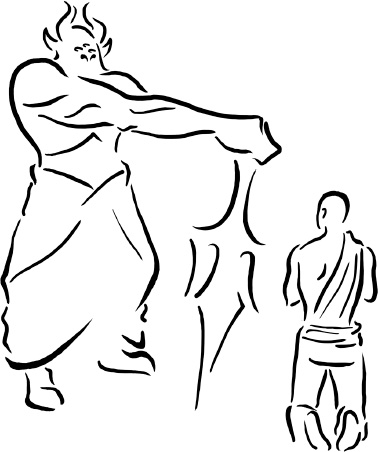

In the Kaṭha Upaniṣad, where we come across this mantra, we also find a classic example of the teacher and student relationship. In the story, a sage performs a particular sacrifice in which he agrees to give away all of his possessions. However, the sage shirks on his promise and only gives away the most spent and aged cows of his herd. The sage’s son, Naciketas, is a dedicated student of the holy traditions, and he challenges his father. Naciketas asks him to whom he should be given, since the son is the possession of the father. His dad scoffs and ignores him twice. But, on the third asking, his agitated father finally promises to give young Naciketas to Yāma, the god of death.

Naciketas arrives on death’s doorstep and waits for three days. Death is always terribly busy. When Yāma arrives home to find someone waiting for him, which is really never the case, he is surprised and pleased. In his delight, he offers Naciketas three boons — a common tradition among the gods of the yogic pantheon. For his first wish, this bighearted young man asks that Yāma return him safely and alive to his father, and for his father not to be angry with him. His second wish is for the secrets of a fire ceremony that is named for him. Third, and most importantly, Naciketas asks Yāma to reveal to him the secret behind death and the truth of immortality.

Even venerable Yāma is shaken by this request. To tell the secrets of his own work and reveal the everlastingness of all that is? Death tries to avoid the boon by offering Naciketas anything and everything else. But Naciketas is a smart young man and denies all these offers; he sticks to his guns. He wants the answer to the meaning of life.

Finally, Yāma relents and describes the true nature of the self and its oneness with all things. He reveals that the death of the body is merely an illusion, as the ātman, or soul, carries on long after the body is shed. He tells Naciketas that basically his role as Yāma is to reveal the truth of what we truly are: Supreme Source. He informs Naciketas that the soul is never born, and never dies, and when a human being clearly perceives this persistent, tiny flame within the heart, the truth of their existence is verily revealed.

The true job of any teacher is, first, to see this truth or numinosity within the student and then, second, to offer teachings that successfully guide the student to their own realization of that truth. Nothing more, nothing less. The discernment of the teacher is paramount in this kind of revelatory work. In the Upaniṣad, we see that the ferocious god of death even exercises caution in revealing this profound truth to the dedicated student, Naciketas. He wants to make really sure that Naciketas has the spiritual foundation, not only to be able to hear, but to absorb the truth. On the flip side, Naciketas asked the right question.

The student and teacher relationship goes both ways. While a teacher’s role is to reveal the student’s inner truth, the student’s role is to locate the right teacher, the one who can reveal this to them. Once this teacher is located, the student is to place faith in that teacher’s teachings. At least for a while. Because even though Yāma’s teachings to Naciketas were wholly profound, Naciketas didn’t stay with Yāma for long. We can surmise pretty easily what would have happened if he had! Remember his first wish? Naciketas first ensured his escape from Yāma’s grasp. Without the ability to leave, he’d be lost forever. He never gave his power away to Yāma in their enlightened exchange. He remained the trusting student while hearing Yāma out, and then once the knowledge became his own, Naciketas parted ways with Death, continuing on to lead his own life as a teacher of the truth.

The most important aspect of the precious teacher and student relationship within yoga is summed up by yoga teacher Mark Whitwell,6 who says, “The guru should be no more than a friend and no less than a friend.”

The Upanishadic and yogic traditions come from a time and culture that revered the learning relationship. This tradition differs from, and sometimes conflicts with, modern Western society, which places different stresses on the individual to challenge authority and value uniqueness and independence. The clash of this original learning modality with its new setting can result in common problems of imbalances of power. Teachers can find it difficult to establish the right boundaries, so that they can successfully impart wisdom while maintaining the kind of respect necessary to place students on equal footing in the relationship. Meanwhile, students may slip into a kind of subservient reverence for a teacher who seems to have all the answers. As in the above quote, the answer to this struggle lies in the idea that this relationship, while friendly, is not friendship. Friendship is sacred and treasured and exists between two people who can laugh, kid, and challenge each other’s ideas. This can be counterproductive in a teacher/student relationship where trust and surrender are key aspects of the student’s ability to learn sometimes very challenging, counterintuitive, and difficult teachings. The teacher and student within the context of yoga exists for one purpose: to guide the student home to their highest truth. This setting requires respect between both parties and a certain amount of reverence for the teachings themselves. In our prolific yogic era, we are lucky to have a wide variety of teachers from whom to seek higher wisdom. As students, we have the responsibility to choose our teachers wisely. In both cases, the respect of this relationship will yield great fruit, as it did in the story of Naciketas and Yāma. When Naciketas saw his opportunity to learn, he took it. When Yāma saw his opportunity to teach, he took it. When the teachings had been given and the point driven home, Naciketas made his exit. And this is, perhaps, the most important aspect of the teacher and student relationship.

The teacher’s role is to reveal the inner truth of the student’s divine self. When that job is done, this relationship must end. This is the final representation of yoga’s ultimate goal, which is liberation. It is counterproductive for a student to remain with a teacher beyond the scope of his or her learning. Interestingly, we find a similar concept conveyed by Jesus (in Luke 6:40): “A disciple is not above his teacher, but every disciple who is fully taught will be like his teacher.” Once again, internal power is always retained by both parties, as both parties can receive a kind of freedom from this sacred relationship. When the student has received what he or she has come for, then either the student must go willingly or the teacher must set the student free.

Ideally, this occurs when we, as students, learn to stand on our own two spiritual feet. When this happens, we have paid the teacher the greatest honor: we have embodied their lessons and made them our own. The truth lives inside us vibrantly and powerfully in such a way that we come to recognize that the teacher’s only work was simply to get us to realize this.

Because, as Yāma told Naciketas, truth resides like a fire, ever-burning, within your own heart. It is ever-present and beyond death. It is who you truly are.