The common mallow has suffered by comparison with its more famous cousin, the marsh mallow, the only member of the family to be an ‘official’ herb. But marsh mallow is rare as a wild plant and moreover is dug up for its root, so for the many soothing qualities of mallow, internal and external, the common form offers a highly effective alternative.

Malvaceae Mallow family

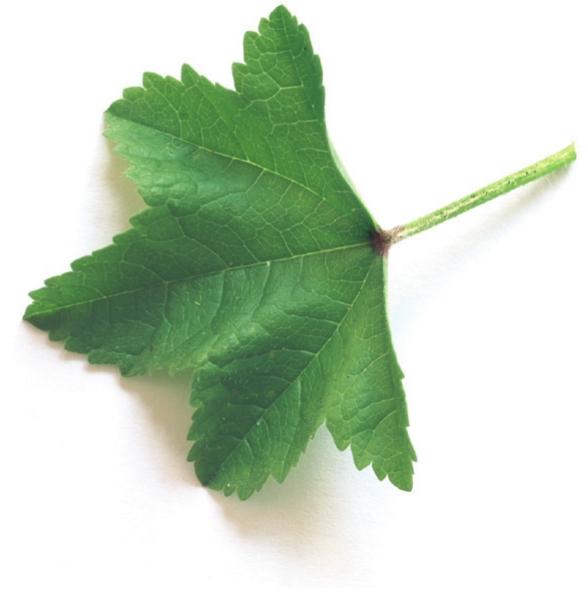

Description: A tall or sprawling perennial growing to 1m with pinkish-purple flowers and ivy-shaped leaves.

Habitat: Hedgerows, bare ground.

Distribution: Common throughout the British Isles except in Scotland and Ireland. Found in Europe and northern Africa.

Related species: Musk mallow (M. moschata) and dwarf or low mallow (M. neglecta) are also quite common. Marsh mallow (Althaea officinalis) is rare, and now only found in the British Isles in southern and eastern coastal areas.

Parts used: Leaves and flowers collected in summer.

The latest official list of British herbs, the British Herbal Pharmacopoeia 1996, describes only one mallow, the marsh mallow (Althaea officinalis), which has become rare in the wild in the British Isles. For commercial use it is now imported from Eastern Europe. The confection ‘marshmallow’ was once cooked from the roots of this plant but has long since ceased to be made of anything herbal.

Its abundantly found cousin, the common, high or blue mallow (Malva sylvestris), has many of the same benefits, so, in the spirit of responsible hedgerow medicine, we recommend its use.

The common mallow does have its advocates, among them Maria Treben in twentieth-century Austria and the journalist and traveller William Cobbett in early nineteenth-century England. Cobbett offers a remarkable encomium of wild mallows, having learned of their value from a French military captive, a follower of Napoleon, in Long Island, New York.

The English farrier, A. Lawson, writing after Cobbett, quotes his own experience of using boiled mallow leaves to treat the badly swollen arm of a nearby farmer and to close a deep wound in a pig that had been gored by a cow’s horn. Lawson quotes Cobbett with approval:

This weed is perhaps amongst the most valuable of plants that ever grew. Its leaves stewed, and applied wet, will cure, and almost instantly cure, any cut or bruise or wound of any sort.… And its operation is in all cases so quick that it can hardly be believed.

For her part, Treben writes of making up a mallow gargle to treat a man with cancer of the larynx. She used the residue of the mallow mixture, mixed with barley flour, as an overnight poultice for the man’s throat. Within two weeks, he was well enough to consider a return to his profession of teaching. The man’s medical specialist said of Treben, ‘this woman deserves a gold medal!’

Mallow from Hortus Floridus (1614–16), by Crispijn van de Passe

At an earlier date, Nicholas Culpeper had written movingly of saving his son from ‘inside plague’ by using a mallow liquor [see quote]. In the sixteenth century and later, mallow had a reputation as omnimorbia, literally a cure-all. This could have because mallow is laxative, and this was thought to rid the body of all disease.

Use mallow for…

While modern-day mallow users would scarcely claim it as a cure-all, they would also say it doesn’t merit official oblivion. Mallow does have solid virtues, and most of these arise from its high mucilage content: common mallow flowers have around 10% mucilage and the leaves 7%. Indeed, all thousand or so members of the Malva family worldwide possess this gelatinous substance, including okra and hibiscus.

Mucilage, a word that is cognate with mucus, is extremely soothing to any inflamed part of the body, both outside and within. This includes dry coughs, colds, gastrointestinal upsets, stomach ulcers and urinary tract infections. As one herbalist notes, when you cannot even swallow water, you can take a mallow tea. Further, it is very safe, in any quantity.

Maria Treben advocates mallow foot and hand baths for treating swellings following bone fractures.

One thing to watch out for in wild-gathering mallow is that its low-growing crinkly leaves tend to accumulate heavy metals from vehicle exhausts and also attract a mallow rust and various insect eggs. So it is a good idea to do your picking well away from busy roads and examine carefully any leaves and flowers you collect.

Mallow is sometimes eaten as a soup, though it is rather ‘gloupy’, and the unripe seed heads make a slightly astringent addition to salads. These seed capsules have long been known as ‘cheeses’, but because of the circular shape rather than the taste. The flowers were chewed to relieve toothache.

Always with mallow, though, you come back to its unrivalled soothing benefits. But do remember that large doses can be laxative as well as purgative! Cicero (106–43 BC) angrily reports being accidentally purged by eating a stew of mallow mixed with beet – and he laments that he had already forgone the oysters in an effort to be good.

Harvesting mallow

Pick the leaves before the plant flowers or whenever they are a bright healthy green. They are best used fresh, although they can be dried.

Pick the flowers and flower buds in summer. They can be used fresh or dried by spreading them out on a sheet of paper in a cool airy place. Mallow flowers turn from pinkish purple to blue as they dry. They can be used on their own as a soothing tea, and make a pretty addition to other herbal tea blends.

Mallow poultice

Chop or chew a fresh mallow leaf and apply to swellings, wounds and cuts. The poultice can be held in place using a sticking plaster or bandage for as long as it is needed. It reduces inflammation as it soothes and heals, so is good for insect bites, boils and abscesses.

Mallow tea

Use a rounded teaspoonful of the dried or fresh flowers or a couple of fresh leaves per mugful of boiling water. Allow to infuse for about 5 minutes, then strain.

Dose: Drink a mugful 3 times a day as needed to soothe the digestion, or coughs and sore throats.

Mallow salad

Mallow leaves and petals make a mild and pleasant addition to a leafy green salad, and make it warmer and more soothing to the digestion.