THE UNFINISHED PROJECT

The Manuscript

In 1936, two Viennese scholars, writing at the end of each day in the elder colleague’s study, worked throughout the summer to complete a book manuscript before the younger of the two departed for London. The final crisis of the postwar Austrian republic gripped the capital and almost certainly the younger scholar would be unable to return to the city in the foreseeable future. The room where they now examined their manuscript became, like Prospero’s cell, a lens through which to view both the pages of their book and the events of the outside world. Their intellectual labors provided them with an independent refuge and a source of solace. But as with Prospero’s island, the shadow of politics intruded continuously at the edges.

The manuscript explored the subject of caricature—the art of comic distortion and willful exaggeration, of irreverence and, according to its most serious practitioners, absolute fidelity to truth. Inspired by recent advances in psychology and by contemporary innovations in art, the two scholars approached caricature not as a low form of creativity or a debased mode of communication but as a distinctive psychological and cultural phenomenon with its own functions and evolution. From the start of their project, they interpreted caricature as an ambitious psychological and artistic experiment, and their effort to grasp each aspect as fully as possible led them to employ theories and methods from both mental science and cultural history.

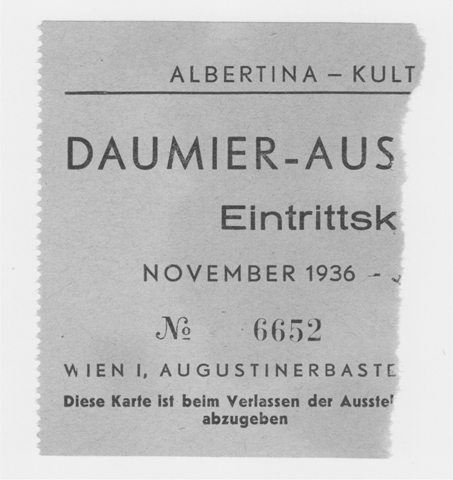

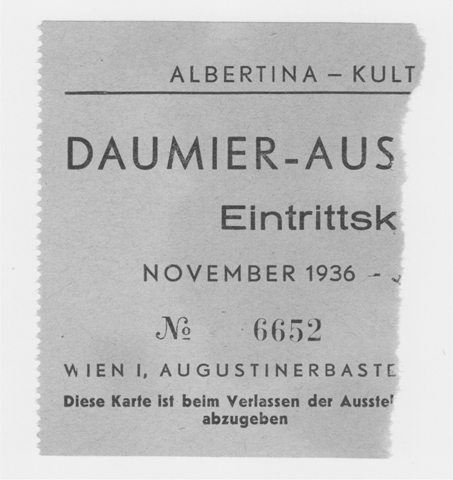

Ticket stub from Daumier’s 1936 exhibition.

But caricature also included political dissent, and the two colleagues intensively explored that side of the experiment as well. In the same, decisive year of 1936—less than two years before the annexation of Austria to Hitler’s Germany—they organized a Viennese exhibition of the work of Honoré Daumier. The art of the nineteenth-century French master of caricature embodied republican, anti-militarist, and internationalist impulses, which now in the 1930s opposed the forces of Austro-Fascism, Church conservatism, and pan-German nationalism that were abetting in the Anschluss with Nazi Germany. Bringing Daumier to Vienna, the two colleagues assembled the largest exhibition of the artist’s works to appear outside of France since the First World War. The year following the exhibition, they completed their book manuscript. Here, in two hundred and fifty-four typescript pages, they traced the evolution of caricature from a Renaissance offshoot of portrait painting to a modern republican art form.

The elder scholar—whose private study served as both haven and workshop—was Ernst Kris, an art historian who had become a leading psychoanalyst within Sigmund Freud’s circle in Vienna and a crucial pioneer of the new psychoanalytic ego psychology. As a university student, Kris had trained in the Vienna School of Art History, but soon after graduating he felt the influence of Aby Warburg’s Library for the Cultural Sciences in Hamburg. Kris’s gravitation toward the Warburg circle and their investigations into the psychology and history of image making coincided with his shift toward psychoanalysis, and the two tendencies produced mutually reaffirming, although not identical, intellectual directions.

Kris’s colleague on both the caricature manuscript and the Daumier exhibition was E. H. Gombrich. Also trained as an art historian in the Vienna School, Gombrich acquired, like Kris, a strong interest in the new psychological sciences, especially the new cognitive psychology. Image studies held out for him the possibility of combining art historical researches with studies of mind and perception—and ultimately politics. Like Kris, he found support at the Warburg Library, which by the time he began his work there had been forced into exile from Hamburg and had re-established itself as the Warburg Institute in London.

The Daumier exhibition and caricature manuscript proved to be Kris and Gombrich’s last collaboration in Vienna. The Anschluss forced both to emigrate to Britain, where they joined the anti-Hitler war effort as analysts of Nazi radio propaganda. Kris ultimately moved his family and his political activity to New York, whereas the younger Gombrich remained throughout the war in or near London. Although the two returned to the study of caricature after 1945, their book encountered new difficulties in the postwar world. They never published the prewar manuscript.

Yet, despite remaining unfinished—even because of it—Kris and Gombrich’s caricature project represents a seminal twentieth-century effort at bridging scientific research and humanist scholarship. Nobel laureate Eric R. Kandel argues persuasively that Kris and Gombrich’s psychological and art historical studies—which the caricature project helped initiate—marked out a path that ultimately led from Freudian depth psychology to neuroscientific models of brain functioning, perceptual processing, and artistic creativity.1 Their study of caricature tested new psychological theories about mind and culture, articulated novel psychoanalytic conceptions of the ego and creativity, and helped to inspire Gombrich’s own landmark theories on cognitive psychology and image making. It combined scientific questioning and humanist research not to produce a single, unified theory but to explore ways of integrating a broad range of concepts and methods. Their project thus offers insight into the kinds of collaboration, questioning, and support that such integrative efforts require in our own time—and will continue to require in the future.

The project also derives significance from another source. Kris and Gombrich’s most extensive work on the caricature manuscript co-incided with the emergence of the antifascist culture of the 1930s, and it derived impetus from that culture. But as a response to the European-wide crisis, it also became absorbed by that crisis. Yet, as historians and social theorists such as Herbert Marcuse and E. P. Thompson emphasized after the war, unrealized potentials offer vital—perhaps the most vital—subjects for historical inquiry. In the aspirations that moved them, in the obstacles that they confronted, and in the choices that they represented, such potentials possess ongoing relevance. The following chapters then do not set forth a dual biography of the two scholars, nor do they present an analysis of the corpus of their works across their careers. Rather, they trace the stages, possibilities, and outcomes of a joint project and shared inspiration from which we can still learn today.

A Model of Integration

According to his Viennese psychoanalytic colleague Robert Waelder, Kris was “at home in both history and psychoanalysis.”2 But while Waelder saw this dual background as an exemplary model for professional training, Kris felt ill at ease with his divided career and treated his double education in art history and psychology as a highly problematic ideal. His persistent efforts to fuse his humanist training with his scientific pursuits never gave rise to a complete sense of personal fulfillment or intellectual satisfaction.3

Ambivalence, however, stimulated theory building. In his psychoanalytic studies of art and creativity, Kris developed the idea of regression in the service of the ego, which he introduced in 1934 in his first essay on caricature. There, and throughout his career, he argued that the creative liberation of unconscious primary processes strengthened rather than detracted from the functioning of the ego. Regressive mental processes did not necessarily lead to inward dissolution. Instead, through controlled regression or mental play the ego achieved an integration of psychological functions and impulses—what Kris described as a restitution of the self. Regression fostered a questioning of received notions from the past and restitution demanded new visions of the future. Both defined a psychological and historical condition of openness, ambiguity, and crisis, a process confirmed by Kris’s own personal and political experiences.4

In the field of cultural history, Aby Warburg had devoted a lifetime of research to exploring the process of regression and restitution.5 In pathbreaking studies of Renaissance artists and their Florentine patrons, he emphasized the ambivalence and instability—the Janus-like nature—of creativity and image making. Images served both as repositories of historical memory and as symbols of an idealized future, expressing simultaneously the violence of primal emotional needs and the promise of modern spiritual ideals. Renaissance painters and their patrons, according to Warburg, revived ancient symbols in a restless, always tentative search for psychological and cultural equilibrium. Warburg’s concern with the “afterlife of antiquity”—the cultural appropriation of a buried and forgotten visual world—would resonate in Kris’s work as he charted the processes of regression and restitution, of creative disintegration and reintegration, in both art and psychology. Maintaining contact with the Warburg Library after its escape from Hamburg for London, Kris relied on it to secure his friend and colleague Gombrich a way out of Vienna.

Initially as a research fellow and ultimately as director of the Warburg Institute, Gombrich carried out groundbreaking analyses in the psychology of perception and artistic representation. Kandel identifies the research that Gombrich undertook with Kris as a pivotal contribution to understanding the function of the brain as a “creativity machine” and to recognizing the psychological role of the beholder in completing the artist’s creative work.6 For Gombrich, artist and audience participated in the mutual construction of meaning. While he rejected Freud’s theory of the unconscious in art—in fact, it eventually became an intellectual irritant to him—as well as Warburg’s conception of historical memory, he did share Freud and Warburg’s fascination with how artists and the public engaged in mental experimentation with images and how they transfigured visions from the past into workable models of the present. Throughout a long and tireless career, Gombrich continued to draw upon both experimental science and cultural history to interpret shifts in artistic perception and creativity and to analyze the psychological ambiguities and historical variations to be found in visual artefacts. He approached images as mental constructs, whose reception, modification, and alteration could be understood as both a cognitive and cultural process. His work with Kris on caricature became his first in-depth study of that dual process.

An impressive amount of material survives from the caricature project. Gombrich never discarded the prewar book manuscript, and as will be seen, he continued to revise it into the 1960s. The original German version and Gombrich’s English translation, with later revisions, belong to the papers of the E. H. Gombrich Estate deposited at the Warburg Institute Archive. After emigrating to Britain, Gombrich also wrote, in English, a highly condensed version of the caricature manuscript, to which he added his own appendix; this abbreviated text can be found in the Ernst Kris Papers at the Library of Congress, while the appendix remains part of the Gombrich Estate. Finally, the Gombrich Estate contains a revised, thirty-five-page outline for the caricature book that Gombrich produced a few years after the war, when he and Kris planned to return to the manuscript.

Correspondence between Kris and Gombrich, preserved in the Kris Papers and the Gombrich Estate, dates from 1936, when Gombrich became a research assistant to Fritz Saxl, the Warburg Institute director in London.7 Trained like Kris and Gombrich in the Vienna School, Saxl became Warburg’s close collaborator after the First World War and, with Gertrud Bing, his designated successor and guardian of the library. Saxl sponsored the only public presentation by Kris and Gombrich on caricature—a lecture that Kris delivered at the Warburg Institute in 1937—and even considered publishing their book.

The Anschluss in 1938 forced Kris, his wife Marianne Kris, and their two young children, Anna and Anton, into exile in London, where he joined the BBC monitoring service as an analyst of German radio broadcasts. On his recommendation, the BBC offered a position to Gombrich, who joined the listening post in late 1939. A year later, Penguin Books published a highly abbreviated history of caricature that Gombrich had authored before the outbreak of the war. English reviews of the pamphlet-length publication—including a highly supportive piece by Herbert Read for The Listener—appeared in 1941, by which time Kris had emigrated to New York and taken a position on the Graduate Faculty at the New School for Social Research. There he received support from the Rockefeller Foundation’s Project on Totalitarian Communication to undertake a detailed study of Nazi radio propaganda.

After the war, Kris offered courses at the New York Psychoanalytic Institute and directed research into early childhood development at the Yale Child Study Center, receiving an appointment in 1949 to the Yale University faculty.8 In London, Gombrich returned to the Warburg Institute as a teaching and research fellow but without a permanent position until 1948. His academic prospects changed dramatically in January 1950 with the appearance of his first monograph on art history, The Story of Art. The book earned nearly instantaneous success. Five months after its appearance, Oxford offered Gombrich the three-year Slade Professorship in Fine Arts.9

Despite the geographic and professional distance between them—soon after the war Kris became a naturalized American citizen and Gombrich a naturalized British subject—the two scholars attempted to revive the caricature book.10 Yet, instead of reinvigorating the project, the early 1950s brought the story of the book to a close. In 1952, Kris published Psychoanalytic Explorations into Art, which collected essays from the previous two decades. Its topics ranged from metapsychology and clinical studies to literary criticism and aesthetic theory. Responding to intense postwar interest in both psychoanalysis and the increasingly popular field of applied psychology, the volume revealed an anti-reductionist temperament and interpretive range not easily matched by other psychoanalysts and psychologists. Yet, Kris regarded his essays—even those with prewar origins—as works in progress, as conscious experimentation with several lines of thought. Among them was the paper on caricature presented to the Warburg Institute, which Kris revised and included in the volume, and which now represented the final outcome of the caricature project.

After the collection appeared in print, Gombrich wrote to Kris that he regarded their Warburg Institute presentation as an important accomplishment. Stressing the significance of context for the interpretation of art, he stated: “It [context] is the problem which does justify a ‘history’ of art and I still think that in this respect our caricature paper is quite a model of ‘integration’.”11 Like Kris, Gombrich saw in their caricature project a work of unrealized potential.

Daumier and the Choice of Caricature

In the ancient world, Plutarch—the Stoic moralist and Delphic priest—compared his aims as a biographer to those of a portraitist who searched both for character traits and for oracular signs within his subject’s visage. The resulting biographies—like portraits—offered both the illusion of life and a symbol of the soul:

When a portrait painter sets out to create a likeness, he relies above all upon the face and the expression of the eyes and pays less attention to the other parts of the body: in the same way it is my task to dwell upon those actions which illuminate the workings of the soul, and by this means to create a portrait of each man’s life.12

In the Renaissance, portraitists reaffirmed the ancient conviction that a natural likeness of the body revealed hidden features of the soul. At the same time, according to Kris and Gombrich, they initiated the modern experiment with caricature. As the two scholars explained, caricaturists regarded supposedly natural likenesses as idealized or, at best, partial configurations. To communicate the soul’s inward truth required that artists distort or reconfigure its external mask.

Seen as a process of de-idealization, caricature represented an innovation in portrait art, a radical psychological and artistic pursuit within the classical tradition, one that preserved an unobtrusive, even guilty, appeal to the humanist imagination. It persisted well beyond the Renaissance as the private creation of artists and a safe indulgence enjoyed by patrons—and perhaps especially by scholars. The composer Felix Mendelssohn drew caricatures of actors and fellow musicians: in 1845 he published in the notorious British satirical magazine Punch a group caricature of the chorus then appearing in Sophocles’ Antigone.13

During the early nineteenth century, other caricaturists produced similarly entertaining and uncontroversial depictions of another sort of theater: the society of manners of the successful bourgeoisie. In such cases, their art remained a private amusement, an entertainment for an audience who could be let in on the joke without danger. Still other caricaturists, however, took far deeper and wider aim, targeting the injustices of the middle-class political and social system. Daumier and his colleagues regarded caricature not merely as a psychological and artistic instrument but as a civic action. In their hands, caricature became more than an alternative symbol for the soul: it documented social and political realities.14

Commentaries on caricature reflected its expansion. In Daumier’s time, critics interpreted it as a response to everyday human folly and as an extension of the Romantic rebellion in art, as an examination of character and as a satire on society, as a creation of the salon and as a product of the street. Balzac referred to its technique as “abbreviatory signs,” while Champfleury described its force as a “cry of the people.”15 Henry James perceived in Daumier the adroit manipulator of the bourgeois imago, whereas Baudelaire saw in him the heir to Bruegel and Goya, a figure who lowered the barriers between psychology, art, and politics.

Driven by the question of how an isolated activity of artists and a personal vice of the bourgeoisie became a public, political act of dissidents, Kris and Gombrich explored caricature as a dynamic, multilayered experiment that crossed creative techniques, historical time periods, and social strata. Scholars since have examined in detail caricature’s separate origins in portraiture, satire, parody, humor, and political criticism, and analyzed its distinctive forms and functions in sketching, illustration, journalism, and photography.16 In his own writings, in fact, Gombrich continued to write on subjects—such as cartooning—that reflected his early interest in caricature.17 Yet, the work he and Kris did jointly remains unique in its approach to caricature as a continuous experiment—one with a long history and diverse uses but also, as Kris would write, with its own systematic or inner logic.

In Daumier, the experiment with caricature not only reached its most comprehensive incarnation but also, according to Kris and Gombrich, ran its course. By the time they brought the French artist’s work to Vienna, they had concluded that caricature’s constant and progressive innovation had come to an end. In their day, it had entered a state of disintegration, splintering into an esoteric play with symbolic forms on the one hand and an ominous, starkly propagandistic manipulation of thought and images on the other. The nationalist, anti-Semitic, and violent propaganda of the twentieth century did not represent to them the latest stage in the development of caricature but rather its collapse, a departure from its essential logic, a gross corruption, and a dangerous abuse that required its own study and response. Caricature, in its truest sense, was for them antipropaganda.

Scholarship and Exile

In exile, Kris and Gombrich shifted to the analysis of fascist propaganda, and waited for an opportunity after the war to revive their manuscript. In their commitment to both scholarship and war work—and in the difficulties they encountered in the pursuit of each—their situation recalls that of another refugee who shared ties to the Warburg Institute. In his memoir of émigré life in London from 1933 to 1936, Felix Gilbert—the great-grandson of Felix Mendelssohn—described his efforts as both a young Renaissance historian and a German refugee to salvage his career in a new country. His research into theories of the state, which combined his interests in cultural and political history, found no counterpart within the British academic universe: “I was surprised and somewhat shocked when I discovered that in England in the 1930s study of the Renaissance was left almost exclusively to art and literary historians.”18 Gilbert’s focus on Niccolò Machiavelli and the rise of modern political theory received an indifferent and even cold response from British academics who still perceived Machiavelli as “an advocate of the devil.”19 Gilbert’s political marginality as an antifascist compounded his intellectual alienation. He observed that the British political class—with the exception of Churchill’s immediate circle and members of the Liberal party—remained smug or unconcerned toward Hitler.

Devoted to scholarship but without an institutional home, preoccupied by events in Germany but unable to influence them, frustrated by British myopia but with no access to opinion-making circles, Gilbert spent his days alone or among fellow exiles. At work he secluded himself in the Reading Room of the British Museum; in off hours he walked across the road to the bookshop of the German émigré Hans Preiss, where he conversed and debated with other anti-Hitler émigrés. The juxtaposition of museum and bookshop became a vivid reminder—and emblematic symbol—of the divided lives led by refugee scholars.

In 1937, in one of the first issues of the British Journal of the Warburg Institute, Gilbert published a commentary on Machiavelli and Florentine thought—his first article on Machiavelli in English, his first scholarly publication in exile, and a veiled self-examination.20 In Florentine archives he had found an unpublished Renaissance dialogue composed circa 1533 by Luigi Guicciardini, the brother of the renowned historian Francesco Guicciardini.21 Machiavelli, who had died several years before the date of the manuscript, appeared as a character in the dialogue, and his presence in the otherwise unexceptional work intrigued Gilbert. The only non-contemporary figure and the only participant who avoided a stock philosophic or religious stance, Machiavelli played the role of intellectual gadfly, the figure who set the dialogue in motion, in Gilbert’s words, “the man who keeps the discussion alive by contradiction. Taken to task for his constant questions and objections, he declares quite openly that, for him, doubt is the beginning of all knowledge.”22 Unashamed, Machiavelli reminded his interlocutors of the power of necessity and especially the decisive role of materialism and selfishness in all human behavior: “Luigi Guicciardini, although he, like most of his contemporaries, saw mainly the paradoxical and contradictory features in Machiavelli’s theories, nevertheless was aware of something more behind this mask of foolery.”23

Guicciardini had aimed at producing a safe, acceptable philosophic and religious meditation. Yet, the presence of Machiavelli as Doubt betrayed a political thinker’s nagging sense of disillusionment with human behavior.

Gilbert’s analysis of the dialogue served as his own meditation on the unremitting conflict between scholarly withdrawal and the political impulse. Confronting that conflict in London, he produced a new historical image of Machiavelli—not the devil of British academic and moral imagination but a Mephistophelean spirit who led others first toward intellectual doubt and skepticism and from there into active political engagement. As in Guicciardini’s dialogue, the movement from Doubt to political activity described not a self-confident, self-fulfilled journey but a conflicted, Faustian crisis. New knowledge of humanity brought with it an alienating, pessimistic appraisal of human action and motives. Machiavelli as Doubt reflected the fatalism that hounded all political commitment, the oppressive duality that fueled Gilbert’s reinterpretation of Florentine thought.

In the mid-1930s both Gilbert and Kris had lost a strong intellectual foothold within traditional academia, but each had found a sympathetic hearing at the itinerant Warburg Institute. Through an analysis of Machiavelli and the Florentine origins of modern political science, the Berlin émigré tried to draw Renaissance scholars away from an exclusive focus on art toward engagement with contemporary political concerns. Through the study of caricature and the display of Daumier’s artwork, the Viennese scholar sought to inject political concerns into the field of art history itself. But what plagued Machiavelli and Gilbert also vexed Kris—and Gombrich. As the two Viennese exiles moved from scholarly isolation toward political engagement, they, like Gilbert, confronted their deepening pessimism about the fate of Europe, a pessimism that the two Viennese never entirely shook off.

All three scholars found a way into the intelligence services. By the time that his commentary on Machiavelli appeared in print, Gilbert, who belonged only to the periphery of the Warburg Institute, had emigrated to the United States, where he took a temporary teaching position at Scripps College in 1936. During the war he served in the Central European Section of the Research and Analysis Branch of the Office of Strategic Services (OSS). There his functions included studying German propaganda, through which he worked at “finding out about the situation inside Germany, and about the ‘mind of the German people.’ ”24 Similar to Gilbert, Kris and Gombrich tracked Nazi radio broadcasts and tried to assess, in Kris’s words, “the enemies’ intentions.”25 In each case, the requirements of war work staved off emotional pessimism and political despair.26

Personal fatalism and political engagement expressed themselves differently in Kris and Gombrich. Kris, who had always sympathized with the ideal of a liberal Habsburg monarchy, eventually identified with and promoted Popular Front principles and strategies. He perceived the necessity of an antifascist alliance with the Left and took solace during the war from the rise of popular antifascist movements, although he questioned their ability to persist beyond the war. Gombrich, who did not identify strongly with the Popular Front, experienced a greater sense of disillusionment and felt a stronger temptation to withdrawal. Throughout the war, he continued to battle against a persistent fatalism, a struggle that gave personal urgency to his political reflections and wartime activities. After 1945, his pessimism about social progress only deepened. Gombrich’s concentration on visual schemas and techniques of representation opened a new field of psychological inquiry into art, but it also reflected a persistent warding off of his brief yet determined engagement with politics.27

A Humanist Experiment

To stress the role of politics in Kris and Gombrich’s study of caricature means also to acknowledge distinct limits. As scholars, they did not share Gilbert’s focus on political thought. Within the world of central European psychoanalysis, Kris never belonged to that group of German-speaking analysts whom Russell Jacoby, in his study of the migration of European psychoanalysis to the United States, described as the political Freudians.28 In the early 1930s, Kris saw no practical linkage between Freudian depth psychology and Marxist social philosophy and he rejected the program of those analysts who sought to bridge the two theories. Gombrich himself asserted flatly, “I have always been nonpolitical,” explaining further that as a young liberal in his university days he associated the activity of politics with “mass processions.”29 As an art historian, he criticized efforts to join political and sociological, and especially Marxist, analysis to the interpretation of images. He finally adopted Karl Popper’s antihistorical positivism and adamantly rejected Arnold Hauser’s social history of art.

Unquestionably, the caricature project began as a collaborative effort in the psychology, not the politics, of art. That said, three crucial points should be noted. First, a project that began with the intent to bridge psychology and image studies ultimately called for methods of political and historical analysis. Second, both the Daumier exhibition and the book manuscript served as important steps toward direct political analysis and engagement during the war. Finally, Kris and Gombrich’s manuscript did not take shape in a vacuum. Having persisted through decades of social upheaval, war, and exile, the caricature project came to an end under altered cultural and political conditions in the 1950s. The new Cold War atmosphere, as well as changes in the sciences, humanities, and visual arts, made it more difficult to pursue the model of integration. A new sense of pessimism supplanted in both scholars the political inspiration that had supplied a critical motive to the project and that had held it together despite differences over interpretation.

Like caricature itself, Kris and Gombrich’s project never took on the shape of a finished masterpiece. It remained instead a suggestive, illuminating, and essential experiment in psychology, art, and politics. What follows is a history of that experiment.