THE GOOD FIGHT

Springfield, Illinois.

Lincoln will later remember this evening as “dark, rainy and gloomy.” The weather might not have bothered the forty-nine-year-old lawyer so much if he had won the election held this day, but, despite all his efforts, he has been defeated.

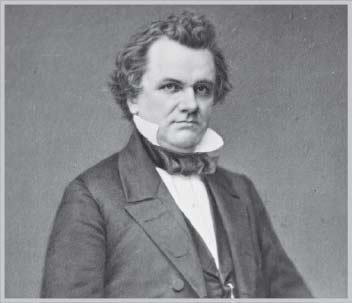

The winner, Stephen A. Douglas, will return to Washington for another term as an Illinois senator. Although Illinois is a free state, its position as a gateway to the American West makes the question of slavery in the new states and territories important to its citizens. Today’s vote centered on it.

Douglas supports slavery. When his late wife inherited a family plantation, Douglas took over its management, and he has continued in that role. (Though for political appearances he has never held direct ownership of the slaves, they are effectively his.) Following the Mexican-American war, as chairman of the Senate’s Committee on Territories, he helped craft the Compromise of 1850, a set of laws that required northern states to return escaped slaves, and which allowed the residents of some of the western territories to decide for themselves if they wanted slavery. Four years later he shepherded the Kansas-Nebraska Act, which gave voters in those territories the right to decide if they wanted slavery. Of course, slaves weren’t allowed to vote. (Neither were women.)

After the Kansas-Nebraska Act was passed, Lincoln, like many others with a strong antislavery position, joined a new political party, the Republicans. A few months before this evening, Illinois Republicans nominated Lincoln as their candidate for the U.S. Senate.

Stephen A. Douglas (1813–1861). Historian Albert Bushnell Hart said, “Douglas was a masterful man of great intellectual power, indomitable energy, shrewdness in forming political combinations, and little scruple [morality]. He was probably the only man in Congress who would have ventured or could have carried through the Kansas-Nebraska bill, a voluntary offering to the south by a northern Democrat.”

Lincoln accepted the nomination with a speech that has become famous. His “House Divided” speech alluded to a Bible passage (Matthew 12:25) that reads, “Every kingdom divided against itself is brought to desolation; and every city or house divided against itself shall not stand.”

A house divided against itself cannot stand. I believe this government cannot endure, permanently, half slave and half free. I do not expect the Union to be dissolved—I do not expect the house to fall—but I do expect it will cease to be divided. It will become all one thing or all the other. Either the opponents of slavery will arrest the further spread of it, and place it where the public mind shall rest in the belief that it is in the course of ultimate extinction; or its advocates will push it forward, till it shall become alike lawful in all the States, old as well as new—North as well as South.

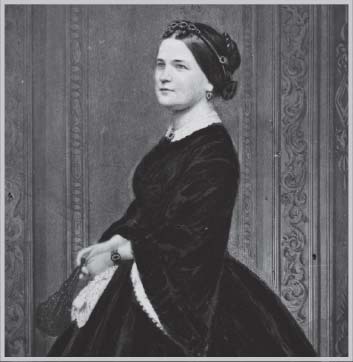

Mary Todd Lincoln (1818–1882), Abraham Lincoln’s wife. From a wealthy and prominent Kentucky family that had many political connections, her energy and uninhibited spirit were apparent from childhood. She moved to Springfield, the capital of Illinois, when she was about twenty, and was courted by several distinguished men, including Abraham Lincoln’s future political rival, Stephen A. Douglas. The Civil War caused her to be separated from part of her family, which lived in the South, and she became increasingly anxious, but she and Abraham remained devoted to each other even when she developed what seems to be a mental illness. This photograph is believed to have been taken while she was First Lady, some time between 1860 and 1865.

Its advocates will push it forward, till it shall become alike lawful in all the States. Lincoln knew that many people who opposed slavery believed it would disappear by itself if were left alone. This was wishful thinking. The Founding Fathers had fooled themselves into believing it when they wrote the Constitution. They hoped it might last just another twenty years, to 1808, by which time new waves of immigrant labor from Europe would arrive to work on southern farms. They said no further slaves could be brought to the country after that date. But slavery persisted—as did the practice of looking the other way to maintain peace between the states.

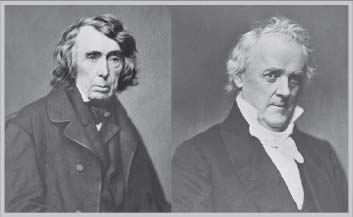

Lincoln, too, had once hoped slavery would die on its own. But now he saw clearly that powerful men in the U.S. government were trying to make it law throughout the country. Along with Congress, both the president, James Buchanan, and the Supreme Court had recently shown a bias toward slavery. In the case of a slave named Dred Scott, who had been taken to the free state of Illinois for a long period and who had then claimed his freedom, the Supreme Court had ruled that slaves and their descendants were not and could never become citizens of the United States. They were property regardless of where in the United States they were. The court also ruled that Congress did not have the right under the Constitution to restrict slavery, and that authorities in free states were obliged to protect the property rights of slave owners.

Dred Scott

At left, Chief Justice of the Supreme Court Roger B. Taney; at right, President James Buchanan

President Buchanan was in sympathy with slave owners. (His late household partner had been one.) Ignoring the Constitution’s separation of government powers, Buchanan had worked with the chief justice of the Supreme Court, Roger B. Taney, to craft the Dred Scott decision and its public announcement. The Dred Scott decision is now almost universally acknowledged as a disgrace—an abomination of legal and human values. But when Lincoln debated Douglas, it was the law of the land.

“POPULAR SOVEREIGNTY”

In the months before this election night, the battle of ideas between Lincoln and Douglas became a national phenomenon. The two men held seven debates that were reported in newspapers across the country. These were huge events: Thousands of people came to hear the speakers, often traveling long distances by train. The campaign staffs of each man made sure their supporters showed up by arranging these excursions.

Douglas was a tough adversary. He presented himself as moderate which pleased the many undecided voters who simply wanted to avoid a civil war. All Douglas wanted, he said, was “popular sovereignty”—the rule of the people. Lincoln, said Douglas in one debate, “says that he looks forward to a time when slavery shall be abolished everywhere. I look forward to a time when each State shall be allowed to do as it pleases. If it chooses to keep slavery forever, it is not my business, but its own; if it chooses to abolish slavery, it is its own business—not mine. I care more for the great principle of self-government, the right of the people to rule, than I do for all the Negroes in Christendom.”

Douglas made the solution of popular sovereignty sound like the best of American democracy. But he wasn’t sincere. He didn’t want people from the free states to vote on the question. He didn’t want slaves to vote on it. Like nearly all politicians of the time, he also didn’t want women to vote on it.

Douglas’s limited idea of democracy had already led to extreme violence in Kansas following his Kansas-Nebraska Act. Thousands of people on both sides of the slavery issue had traveled to Kansas from surrounding states and territories to cast a vote on the issue. Where political tricks couldn’t be used to keep the antislavery voters from the polls, proslavery terrorists did the job. (Although often called “guerrillas” in history books, the term “terrorist” is more accurate because civilians were targeted in addition to government forces.) A few antislavery men responded in kind. “Bleeding Kansas,” as it came to be called, was actually an early battleground of what in a few years would formally become the Civil War.

The violence reached all the way to Washington DC. A senator from Massachusetts made a speech criticizing southerners for their role in the violence—a speech that included stupid and cruel comments about the physical disabilities of a senator from South Carolina who had suffered a stroke. A relative of the South Carolina senator, a congressman himself, approached the Massachusetts senator in the senate chamber and furiously beat his head with a cane until the cane broke. It was revenge for both the personal insult and the insult to South Carolina, the congressman said. The injuries he’d inflicted were so severe that his victim would need three years to recover. Back home, the attacker was hailed as a hero. People sent him new canes as gifts.

Lincoln offered a simple reply to Douglas’s insincere call for democracy: The heart of American democracy is stated clearly in the Declaration of Independence: “all men are created equal.”

Douglas knew that most white people considered the equality of African Americans to be a ridiculous notion. Douglas derided Lincoln’s views, saying:

Mr. Lincoln, following the example and lead of all the little Abolition orators, who go around and lecture in the basements of schools and churches, reads from the Declaration of Independence that all men were created equal…. I do not question Mr. Lincoln’s conscientious belief that the Negro was made his equal, and hence is his brother; but for my own part, I do not regard the Negro as my equal, and positively deny that he is my brother, or any kin to me whatever.

Two debates later, he was even harsher:

I hold that a Negro is not and never ought to be a citizen of the United States…. Now, I say to you, my fellow-citizens, that in my opinion, the signers of the Declaration had no reference to the Negro whatever, when they declared all men to be created equal. They desired to express by that phrase white men, men of European birth and European descent, and had no reference either to the Negro, the savage Indians…or any other inferior and degraded race, when they spoke of the equality of men.

As repellent as these ideas are in the present day, Douglas was expressing what a large proportion of Americans believed, and what the U.S. Supreme Court had said in the Dred Scott decision.

“ANOTHER EXPLOSION”

As the debates went on, Lincoln began to win support. Douglas then stooped to a tactic used many times before and since: He called Lincoln unpatriotic and a traitor because Lincoln had criticized the Mexican-American War:

It is one thing to be opposed to the declaration of a war, another and very different thing to take sides with the enemy against your own country after the war has been commenced. Our army was in Mexico at the time, many battles had been fought…. Lincoln’s vote [was] sent to Mexico and read at the head of the Mexican army, to prove to them that there was a Mexican party in the Congress of the United States who were doing all in their power to aid them.

Lincoln was no traitor, and Douglas knew it. But Douglas also knew that at least a few people would be easily fooled with that kind of attack. Still, Douglas’s victory wasn’t by a wide margin. His party won less than half the votes cast. (The voters weren’t actually casting ballots directly for Lincoln and Douglas. They were choosing state legislators who would then choose between the two men.) Lincoln, though saddened by the results of this evening, is determined to press on. He sees no alternative for the country: The slavery advocates are asking for conflict by pushing their claims westward.

A few days from now he’ll explain to a friend, “The fight must go on. The cause of civil liberty must not be surrendered at the end of one, or even, one hundred defeats…. Another explosion will soon come.”